Key points

- Policymakers have poorly defined U.S. strategic interests in the Russia-Ukraine War.

- Those interests that have been defined—deterring future aggression and protecting the “liberal order”—do not stand up to scrutiny.

- Actual U.S. interests in Ukraine are essentially negative: preventing further escalation or spillover of the conflict and limiting a wholesale collapse in U.S.-Russian relations.

- The limited interests that the U.S. does have in Ukraine suggest that Washington should try to convince Ukraine and Russia to accept a negotiated settlement.

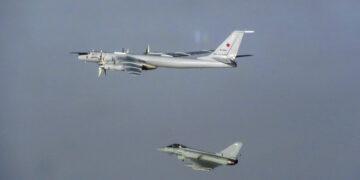

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 understandably produced an outpouring of international support for Kyiv.1Thanks go to Emma Ashford, Benjamin H. Friedman, Lindsey O’Rourke, Christopher Preble, William Ruger, and Stephen Walt for comments on prior drafts. The United States has been in the forefront of these efforts. Even before Russian forces surged across the border, the United States and many of its allies signaled their opposition to Moscow’s ambitions by warning of a range of potential sanctions Russia would incur, working to mobilize a potential diplomatic coalition against Moscow, and bolstering Ukraine’s military forces. Since the invasion, meanwhile, the United States has taken the lead in providing Ukraine with military equipment and training, economic aid, a near-blank check of diplomatic support, and intelligence of use for stymying Russia’s offensive while imposing so-called “crippling” economic sanctions on Moscow. Judging from increasingly fervent bipartisan calls to penalize Russia, Ukraine’s lobbying efforts for additional aid (particularly as it goes on the counter-offensive), mounting calls from many think tankers and pundits to do more on Kyiv’s behalf, and the Biden administration’s gradual increase in support for Kyiv since February, the American commitment seems poised to grow in the future.

Absent from this discussion, however, is rigorous analysis of America’s strategic interests in the Russia-Ukraine War. To be sure, policymakers and pundits have defined specific objectives vis-à-vis Ukraine itself and offered various justifications for U.S. actions. Nevertheless, discussion of how U.S. efforts in Ukraine contribute to overarching U.S. national objectives and interests is mostly lacking, apart from the invocation of broad principles (such as “defending democracy” or “defending the liberal order”). Missing, in other words, is an effort to relate Ukraine to U.S. grand strategy and to evaluate presumed U.S. interests against the real costs and risks of the U.S. effort—including the potential for direct military confrontation with Russia and the further consolidation of a Russo-Chinese axis. Amid the continuing war and calls for the United States to “do more,” the question stands: What are the United States’ strategic interests in Ukraine, and how might the United States best service them?

This report draws on international relations theory, diplomatic history, and U.S. grand strategy discussions to argue that the United States has few core interests at stake in the Russia-Ukraine War. The limited interests that are involved, meanwhile, argue for bringing the conflict to a close irrespective of whether Ukraine triumphs against Moscow. I make this argument with no joy or enthusiasm, as I share the moral outrage at Russia’s actions and would personally prefer to see Ukraine beat back Moscow’s power play. Still, international relations remain a Hobbesian environment in which unpalatable tradeoffs must be faced and hard choices must be made. At a time of growing demands upon U.S. power elsewhere, and considering the stark risks of further U.S. involvement in Ukraine, a tough-minded look at American interests suggests a major adjustment to U.S. policy is in order.

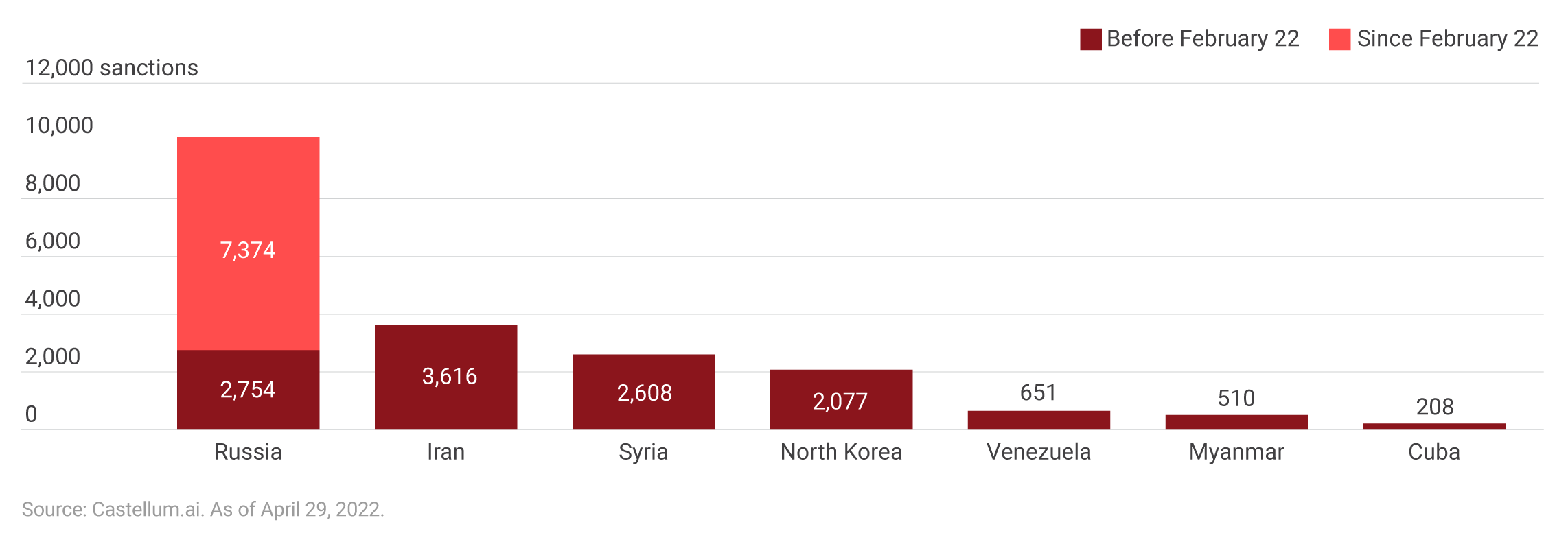

The U.S., Europe, and other nations imposed broad and severe sanctions on Russia

Extensive sanctions imposed on Russia by the U.S. and its partners significantly harmed its economy and, over the long term, its ability to develop and deploy military capability.

Avowed U.S. interests

Although often subsumed amid the rush of events, policymakers and pundits have been quick to declare an abiding American interest in Ukraine. These claims fall into two camps. One line holds that the United States cannot tolerate Russian aggression in Ukraine because it will only encourage further aggrandizement and expanding threats to the United States. This claim comes in two forms. The narrow version holds that the danger of future aggression is from Russia specifically—that is, if Russia goes unchallenged in Ukraine, then Moscow will simply expand its ambitions, challenge the United States’ North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) allies, and ultimately threaten European security writ large. Along these lines, former Ambassador to Russia Michael McFaul argues that “we have a security interest in [helping Ukraine defeat Russia]. Let’s just put it very simply: if Putin wins in Donbas and is encouraged to go further into Ukraine, that will be threatening to our NATO allies.”2“Amb. Michael McFaul: U.S. Has ‘a Major Strategic Interest to Help the Ukrainians Win the Battle of Donbas’,” Yahoo, April 20, 2022, https://www.yahoo.com/now/amb-michael-mcfaul-u-major-183111659.html; Atlantic Council, “Why Ukraine’s Success is in the U.S. National Interest,” YouTube Video, February 4, 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K6OUQe_Za18. Likewise, former National Security Advisor Stephen Hadley asserts that the United States has an abiding concern in deterring Russian President Vladimir Putin “from thinking he can in the next five or ten years repeat this performance.”3See also “Russia’s War in Ukraine: How Does it End?” Council on Foreign Relations, May 31, 2022, https://www.cfr.org/event/russias-war-ukraine-how-does-it-end. See also Alina Polyakova, Daniel Fried, “Putin’s Long Game in Ukraine,” Foreign Affairs, February 23, 2022, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/ukraine/2022-02-23/putins-long-game-ukraine. This particular concern helps explain why at least some in the Biden administration call for “weaken[ing] Russia” by bleeding it in Ukraine: as a National Security Council spokesperson put it, “one of our goals has been to limit Russia’s ability to do something like this again” by undercutting “Russia’s economic and military power to threaten and attack its neighbors.”4Natasha Bertrand, Kylie Atwood, Kevin Liptak, Alex Marquardt, “Austin’s Assertion that US Wants to ‘Weaken’ Russia Underlines Biden Strategy Shift,” CNN, April 26, 2022, https://www.cnn.com/2022/04/25/politics/biden-administration-russia-strategy/index.html.

The broad version links the Ukraine war not to Russia per se but to potential aggrandizement by other actors—especially China. President Biden himself advanced a version of this claim, writing in March that “If Russia does not pay a heavy price for its actions, it will send a message to other would-be aggressors that they too can seize territory and subjugate other countries”; elsewhere, he asserts that “Throughout our history, we’ve learned that when dictators do not pay the price for their aggression, they cause more chaos and engage in more aggression.”5Joseph R. Biden Jr., “President Biden: What America Will and Will Not Do in Ukraine,” New York Times, May 31, 2022, quoted in Robin Wright, “Ukraine is Now America’s War, Too,” New Yorker, May 1, 2022, https://www.newyorker.com/news/daily-comment/ukraine-is-now-americas-war-too. See also Marc A. Thiessen, “If Putin is Allowed to Invade Ukraine, America’s Credibility Would Lie in Tatters,” Washington Post, February 8, 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2022/02/08/ukraine-russia-war-united-states-china/. Rep. Michael McCaul offers a similar take (suggesting its bi-partisan appeal): Failure to act in Ukraine would “embolden Vladimir Putin and his fellow autocrats by demonstrating the United States will surrender in the face of saber-rattling,” concluding that “U.S. credibility from Kyiv to Taipei cannot withstand another blow of this nature.”6Michael Crowley, “Biden’s Stand on Ukraine Is a Wider Test of U.S. Credibility Abroad,” New York Times, December 16, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/12/16/us/politics/biden-russia-ukraine.html. See also https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/09/01/china-taiwan-ukraine-war-lessons/?tpcc=recirc_latest062921.

Taking a different track, a second set of claims holds that the United States has an abiding interest in Ukraine because it affects the so-called “liberal international order.” Along these lines, Secretary of State Antony Blinken asserts, “the international rules-based order that’s critical to maintaining peace and security is being put to the test by Russia’s unprovoked and unjustified invasion of Ukraine.”7Antony Blinken, “Secretary Blinken’s Remarks,” U.S. Department of State, March 4, 2022, https://www.state.gov/secretary-antony-j-blinken-at-a-press-availability-15/. Similarly, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Gen. Mark Milley claims that if Russia’s invasion “is left to stand, if there is no answer to this aggression, if Russia gets away with this cost-free, then so goes the so-called international order” without explaining how or why this is the case. The logic here appears to be two-fold. First, failing to back Ukraine would call into question American support for democracies world-wide, thereby undermining the viability of democracy as a way of organizing any society’s political life. As Biden explained, Ukraine was part and parcel of an ongoing “battle between democracy and autocracy, between liberty and repression;” by implication, not aiding Ukraine would set the United States back in this contest.8Joseph R. Biden Jr., “Remarks by President Biden on the United Efforts of the Free World to Support the People of Ukraine,” The White House, March 26, 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/speeches-remarks/2022/03/26/remarks-by-president-biden-on-the-united-efforts-of-the-free-world-to-support-the-people-of-ukraine/. See also Steven Feldstein, “Ukraine Won’t Save Democracy,” Foreign Affairs, July 26, 2022, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/world/ukraine-wont-save-democracy; Ishaan Tharoor, “The War in Ukraine Underscores a Moment of Democratic Crisis,” Washington Post, April 20, 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2022/04/20/democratic-decline-authoritarianism-ukaine/.

Second, Russian aggrandizement is said to be a challenge to other, mostly unspecified principles—seemingly that powerful states should not use force to impose their writ on weaker actors and that violations of state sovereignty are not to be tolerated—upon which the liberal order supposedly rests. Ignoring Russian aggression would, it is feared, thereby undermine the U.S.-backed postwar “order.” Anne Applebaum captures the concern well, asserting that the U.S. must be invested in the conflict since “the realistic, honest understanding of the war is an understanding that we now face a country that is revanchist, that seeks to expand its territory for ideological reasons, that wishes to end the American presence in Europe, that wishes to end the European Union, that wishes to undermine NATO and has a fundamentally different view of the world from the one that we have.”9Kimberly Atkins Stohr, “As War Drags on in Ukraine, Is It Time to Talk Compromise?” WBUR, June 21, 2022, https://www.wbur.org/onpoint/2022/06/21/ukraine-russia-america-conflict-war-over-applebaum. Also Richard Fontaine, “Why Russia Must Fail in Ukraine,” CNAS, July 6, 2022, https://www.cnas.org/publications/commentary/why-russia-must-fail-in-ukraine; Ivo H. Daalder, James M. Lindsay, “Last Best Hope,” Foreign Affairs, July/August 2022, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/world/2022-06-21/last-best-hope-better-world-order-west; Damien Cave, “The War in Ukraine Holds a Warning for the World Order,” New York Times, March 4, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/04/world/ukraine-russia-war-authoritarianism.html. Put simply, inaction risks empowering alternate principles upon which international order would rest and which, presumably, would harm the United States.

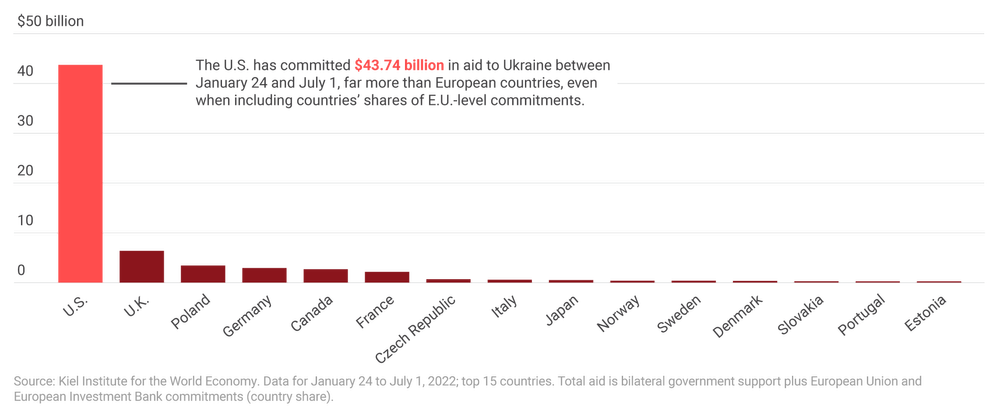

Analyzing claimed interests

These prominent and oft-repeated claims have gone largely unchallenged since the war began. Nevertheless, the United States has run real risks—most dramatically, possible military escalation with Russia—and borne real costs—including aid that exceeds the budgets of the U.S. Transportation, Labor, and Commerce departments combined and significant economic penalties for its citizens—for the sake of helping Ukraine.10Author calculations based on 2021 Federal Budget. See Kelley Griffin, “The Impact of Russia Sanctions on US States,” NCSL, February 28, 2022, https://www.ncsl.org/research/fiscal-policy/the-impact-of-russia-sanctions-on-us-states-magazine2022.aspx; Ira Kalish, “How Sanctions Impact Russia and the Global Economy,” Deloitte, March 15, 2022, https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/economy/global-economic-impact-of-sanctions-on-russia.html; Rebecca M. Nelson, “Russia’s War on Ukraine: The Economic Impact of Sanctions,” Congressional Research Service, May 3, 2022, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF12092#:~:text=Sanctions%20that%20isolate%20Russia%20are,slowdown%20in%20global%20economic%20growth. Illustrating the point, President Biden and other policymakers have acknowledged the economic impact of the American response for U.S. citizens. See Nancy Cook, “Biden Says Inflation Is ‘Hurting’ US Families, Blames Pandemic,” Bloomberg, May 10, 2022, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-05-10/biden-says-inflation-hurting-u-s-families-blames-pandemic; “Biden Says Defending Ukraine Could Cause U.S. Economy Pain,” Bluefield Daily Telegraph, February 15, 2022, https://www.bdtonline.com/news/biden-says-defending-ukraine-could-cause-u-s-economy-pain/article_af47a684-8ea2-11ec-bef8-abb386de921d.html. The combined U.S. Labor, Commerce, and Transport departments budgets totaled $43.8 billion in 2021. U.S. aid to Ukraine from January to July 2022 totaled 42.615 billion Euros, or approximately $42.6 billion at current exchange rates. Author calculations from “Budget of the U.S. Government, Fiscal Year 2022,” U.S. Office of Management and Budget, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/budget_fy22.pdf.

Total government aid to Ukraine

To be sure, the financial costs are not insurmountable at a time when, to judge from interest rates, citizens and governments around the world are essentially giving the United States money. Likewise, many analysts claim that the risks involved are lower than one might think as, for instance, Russia would not be so suicidal as to risk war with the United States and its allies (unless they join the war directly).11For illustration, see Andrew Kydd, “Will NATO Fight Russia Over Ukraine? The Stability-Instability Paradox Says No,” Political Violence At A Glance, March 24, 2022, https://politicalviolenceataglance.org/2022/03/24/will-nato-fight-russia-over-ukraine-the-stability-instability-paradox-says-no/; Andrew Kydd (@AHKydd), Twitter Post, June 11, 2022, https://twitter.com/AHKydd/status/1535810787956097024; Dan Altman, “The West Worries Too Much About Escalation in Ukraine,” Foreign Affairs, July 12, 2022, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/ukraine/2022-07-12/west-worries-too-much-about-escalation-ukraine. Still, tens of billions of dollars remain at stake at a time of rising domestic resource demands, and the fact that policymakers and analysts are debating how threatening American responses are likely to be viewed in Moscow suggests the risks being run are not negligible. It may be impolitic, but sound statecraft means we ought to ask whether the game is worth the candle.

The answer is “likely not.” None of the avowed U.S. interests in Ukraine stands up to careful scrutiny. There is thus a good chance the United States is creating further strategic dilemmas for itself in ways that may only worsen the consequences of the present conflict.

Further aggrandizement: an overstated worry

Worries that failure to act in Ukraine will simply whet Russia’s appetite for European aggression and eventually lead to an attack on America’s NATO allies are questionable. To be sure, some states at some times are dominated by domestic elites convinced that aggression is cheap, easy, and worthwhile.12Jack L. Snyder, Myths of Empire: Domestic Politics and International Ambition (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1991); Randall L. Schweller, “Tripolarity and the Second World War,” International Studies Quarterly 37, no. 1 (1993): 73–103, https://doi.org/10.2307/2600832. Still, to argue that unchallenged Russian behavior in Ukraine will yield further Russian aggrandizement is to argue that there are no other possible constraints that can keep Russian ambitions or behavior in check. Common sense, international relations theory, and current trends in European security all indicate otherwise.

Generations of research finds that states faced with a proximate and militarily ambitious actor tend to balance and check its opportunities for further aggression. In an anarchic world, this sort of behavior reflects the fact that self-interested states have to ensure their own security and so are incentivized to check potential aggressors.13Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War, trans. Rex Warner and M. I Finley (Harmondsworth, U.K.: Penguin Books, 1972); Edward V. Gulick, Europe’s Classical Balance of Power: A Case History of the Theory and Practice of One of the Great Concepts of European Statecraft (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1955); Hans J Morgenthau, Politics Among Nations: The Struggle for Power and Peace, 2nd ed. (New York: Knopf, 1954); Kenneth N. Waltz, Theory of International Politics (Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1979); Karl W. Deutsch and J. David Singer, “Multipolar Power Systems and International Stability,” World Politics 16, no. 3 (April 1964): 390–406; Dale C. Copeland, The Origins of Major War (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2000). As a result, bandwagoning behavior—where weak and/or threatened states give in to aggressors—is rare, and even the defeat of one country tends not to set off a cascade of similar losses; states don’t fall like dominos.14Stephen M. Walt, The Origins of Alliances (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1987); Eric J. Labs, “Do Weak States Bandwagon?” Security Studies 1, no. 3 (1992): 383–416; Robert Jervis and Jack L Snyder, eds., Dominoes and Bandwagons: Strategic Beliefs and Great Power Competition in the Eurasian Rimland (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991). We see these trends playing out in Europe today, where Russia’s actions have spurred both arming (e.g., Germany’s growing defense budget) and allying (e.g., Sweden and Finland joining NATO, renewed interest in European military autonomy). Moreover, the distribution of power in Europe underlines that there are multiple states that, singly or collectively, are more than capable of influencing Russian calculations over both the short and medium-term. In addition, modern warfare appears relatively more favorable to defensive military operations than offensive operations—evidenced today by the comparative success under-resourced and less numerous Ukrainian units have had in blunting Russian offensives in the recent contest, using defense-favoring weapons such as anti-tank guided missiles. This reinforces the feasibility of balancing by allowing a range of states to conclude that resistance to aggression can pay.

Should it ever contemplate future aggression in Europe, Russia will find itself increasingly hemmed in. Even a leader as potentially risk-acceptant as Vladimir Putin cannot easily ignore this situation. Yet even if he—or his successor(s) did—misjudge these constraints, the beauty of balancing is that aggressors soon encounter resistance that thwarts their efforts. Put differently, even a reckless Russia that somehow concludes aggression after Ukraine is viable is unlikely to get very far.

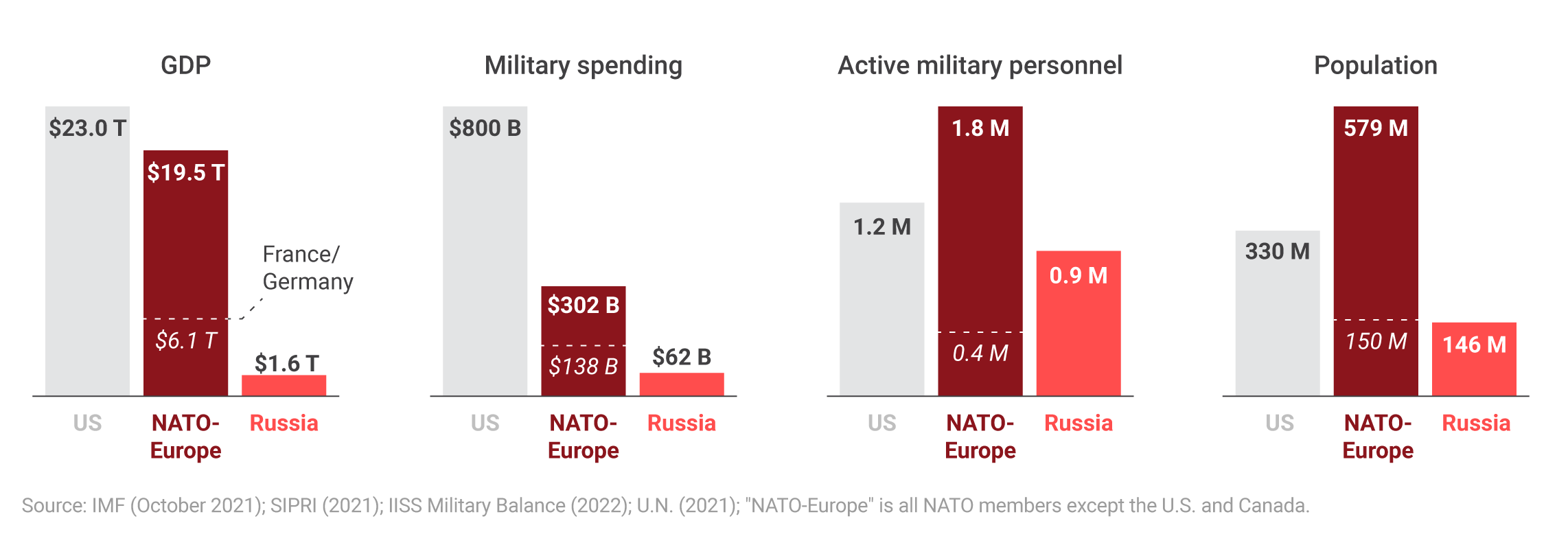

The balance of power between Russia and NATO-Europe

The 28 NATO members in Europe possess the material wherewithal to balance Russia’s military power.

This is doubly true so far as possible aggression against NATO members is concerned. Distinct from efforts to aid Ukraine itself, the alliance has responded to Russian aggression by drawing together to a degree unmatched in the last twenty years; both declared policy and emerging military trends indicate that its members are increasingly committed to defending what Biden termed “every inch of NATO territory.”15For Biden’s comments and commitment, see Ashley Parker and Emily Rauhala, “Biden and NATO Send Russia Defiant Message,” Washington Post, June 29, 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2022/06/29/biden-nato-defiant-russia/. Illustrating the quick reaction to Russian moves, NATO’s newly revised Strategic Concept declared Russia, “the most significant and direct threat to Allies’ security and to peace and stability in the Euro-Atlantic area.” Likewise, allies have begun deploying limited numbers of additional forces along NATO’s eastern flank—with further increases possible—and boosted defense spending. For details, see Robbie Gramer, “Putin’s Invasion Has Turbocharged NATO Defense Spending,” Foreign Policy, June 30, 2022, https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/06/30/nato-defense-spending-putin-ukraine-war/; “NATO Plans Huge Upgrade of Rapid Reaction Force in ‘Era of Strategic Competition’,” France 24, June 27, 2022, https://www.france24.com/en/europe/20220627-nato-plans-huge-upgrade-of-rapid-reaction-force-in-era-of-strategic-competition; Matt Murphy, “NATO Plans Huge Upgrade in Rapid Reaction Force,” BBC, June 27, 2022, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-61954516; “Fact Sheet-U.S. Defense Contributions to Europe,” U.S. Department of Defense, June 29, 2022, https://www.defense.gov/News/Releases/Release/Article/3078056/fact-sheet-us-defense-contributions-to-europe/; “Madrid Summit Declaration,” NATO, June 29, 2022, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_196951.htm. Public opinion within NATO has also noticeably moved against Russia since the invasion; see Tobias Bunde, Tom Lubbock, “How United is the West on Russia?” Washington Post, July 5, 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2022/07/05/nato-russia-putin-threat-opinion-surveys-ukraine-invasion/. The conflict has thus made it abundantly clear that Russia risks an overwhelming (outside the nuclear realm) counterbalancing coalition should it attempt to move against NATO members.16Jill Lawless, Joseph Wilson, Sylvie Corbet, “NATO Vows to Guard ‘Every Inch of Territory’ as Russia Fumes,” AP News, June 30, 2022, https://apnews.com/article/russia-ukraine-nato-putin-madrid-9b249117b645e461f09cd0b4cb4afc02. Combined, there are thus strong reasons to doubt whether any Russian policymaker will conclude further aggression in Europe will pay, or succeed in such a course if it does.17The scope of Russian losses in the present conflict also leaves it debatable whether future aggression in Europe is even practical, particularly given the likelihood of a major European rearmament effort. For this reason, the outcome in Ukraine is not decisive in shaping or thwarting Russian ambitions.

A similar problem applies to claims that failing to act in Ukraine will cause other states, particularly China, to conclude that aggression pays. By this logic, the world is full of potential aggressors that are held in check solely by their fear of an American response; it further implies that aggression anywhere is a direct threat to vital U.S. interests. Arguing that the U.S. must act in Ukraine to forestall others’ aggression is thus tantamount to arguing that the United States must serve as a global police officer that dare not rest even for a moment.

Holding aside that policymakers have long abjured the idea of the United States serving as a global police officer, there are several major flaws in this thinking. First, as Stephen Walt notes, the historical record is replete with aggressors paying exorbitant costs for their behavior—think of Germany’s defeat, occupation, and division following World War II or the firebombing of Japan. Nevertheless, aggression remains a reality in international politics as, even when one aggressor is defeated, others do not readily seem to “learn” the lesson.18Stephen M. Walt, “Will Teaching Aggressors a Lesson Deter Future Wars?” Foreign Policy, June 2, 2022, https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/06/02/will-teaching-aggressors-a-lesson-deter-future-wars/. Note that arguing other states are unlikely to be directly influenced by efforts to punish Russian aggression is distinct from the above claim that Russia may be sobered by its own recent experience.

Second, an array of research indicates that state calculations are shaped not by general impressions of how a single great power may respond but contextual judgments of whether counterbalancing and punishment are likely given the distribution of power and known state interests.19John J. Mearsheimer, Conventional Deterrence (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1983); Copeland, Origins; Jonathan Mercer, Reputation and International Politics (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2010); Daryl G. Press, Calculating Credibility: How Leaders Assess Military Threats (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2005). For a helpful discussion of recent research and analytic distinctions bearing on the topic, see Joshua D. Kertzer, “American Credibility After Afghanistan,” Foreign Affairs, September 2, 2021, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/afghanistan/2021-09-02/american-credibility-after-afghanistan. Aggression turns, that is, on the present, local circumstances. Extending the point, the United States can afford to ignore Ukraine without risking aggression in other theaters provided it has the interest and wherewithal to act in these other areas, or there are local actors able and interested in acting similarly. This makes intuitive sense: Beijing (among other potential challengers) is likely to care far more about what the United States, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, India, Australia, etc. can and will do in Asia than it cares about what the United States does 4,000 miles away. Analysts that treat the outcome in Ukraine as the decisive factor determining whether other states will choose war overlook the real geopolitical conditions that are likely to shape others’ interest in and opportunities for aggrandizement.

Third, one ought to treat the idea that aggression anywhere constitutes a threat to the United States with skepticism. Even a cursory glance at the diplomatic record underlines that the United States is not truly threatened by aggression in and of itself. In recent years alone, the Russo-Georgian War, the Saudi campaign in Yemen, fighting between Ethiopia and Eritrea, and other episodes have had little impact on U.S. well-being. Further back, it took the prospective emergence of a European hegemon to draw the United States into the two world wars and Cold War, and even then the strategic threat to the United States was uncertain.20For illustration, see John A. Thompson, A Sense of Power: The Roots of America’s Global Role (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2015); Nicholas John Spykman, America’s Strategy in World Politics: The United States and the Balance of Power (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1942); Melvyn Leffler, A Preponderance of Power: National Security, the Truman Administration, and the Cold War (Redwood City, CA: Stanford University Press, 1992); Marc Trachtenberg, A Constructed Peace: The Making of the European Settlement, 1945–1963 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1999). This is the advantage of being a rich and insulated great power surrounded by ocean moats—not to mention possessing a large nuclear arsenal.

Finally, even if it were true that the United States had an interest in forestalling most aggression, it does not follow that further involvement in Ukraine constitutes the only or best way to signal that the United States will penalize aggression more generally. After all, the United States can not only—as previously suggested—take steps to reinforce its ability to thwart aggression irrespective of what happens in Ukraine, but so too can it penalize Russia aggression to signal its commitment by, for example, encouraging a NATO build-up in Eastern Europe and maintaining targeted sanctions on Moscow.21A third objection—that states cannot credibly signal their future intentions at all—is also possible. This logic would suggest that acting in Ukraine as a deterrent to aggression more generally is simply not feasible as others will discount the implications of U.S. policy in Ukraine for any and all future scenarios (presumably falling back to contextual judgments of capability and interest). See Sebastian Rosato, Intentions in Great Power Politics: Uncertainty and the Roots of Conflict (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2021).

Threats to order: theory, not reality

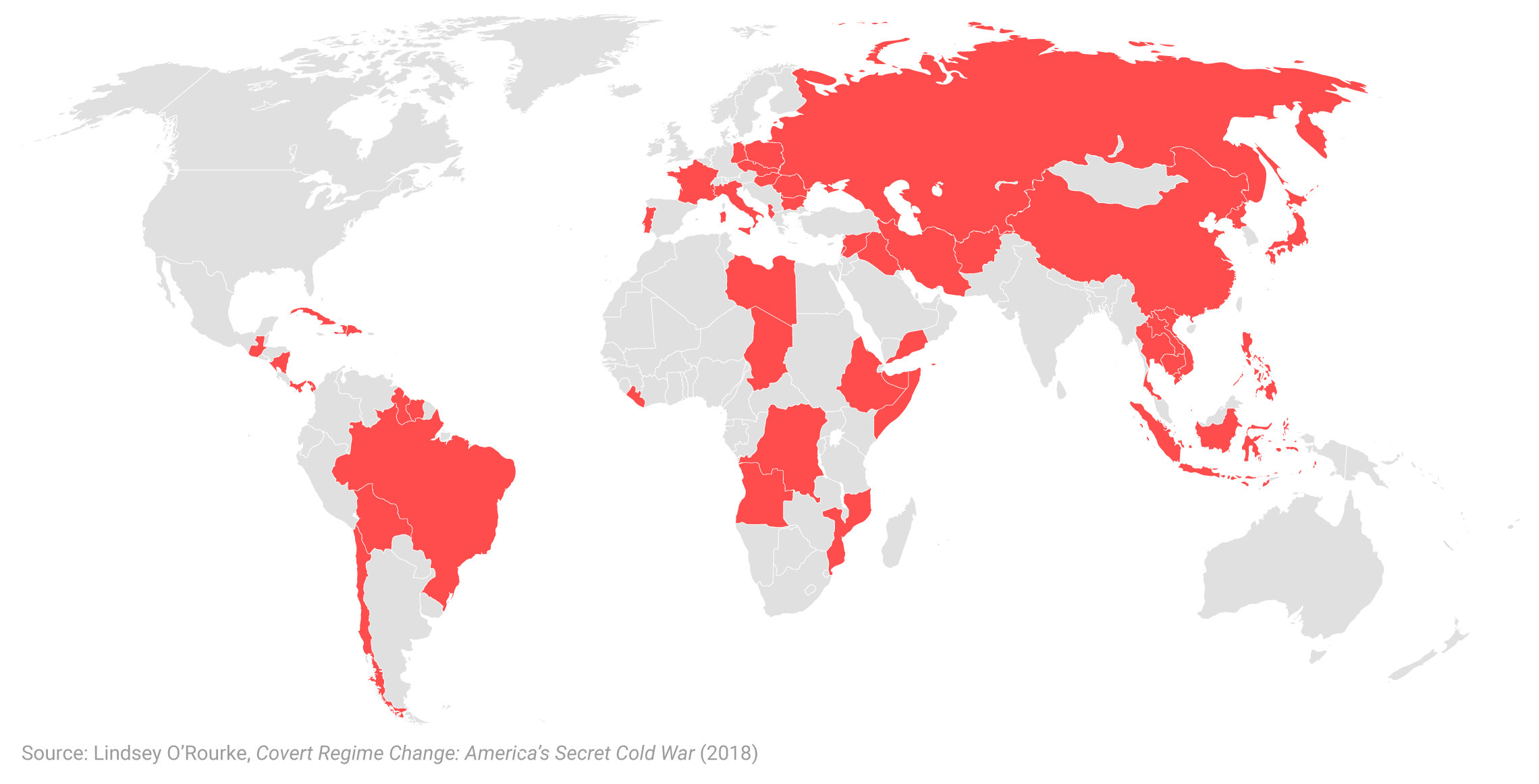

Assertions that neglecting to act in Ukraine will undermine the liberal order are similarly suspect. First, although the United States has sought to promote democracy abroad, it balanced this impulse with careful consideration of geopolitical imperatives regardless of how this affected democracy’s spread.22Michael Cox, Timothy J. Lynch, and Nicolas Bouchet, eds., US Foreign Policy and Democracy Promotion: From Theodore Roosevelt to Barack Obama (New York: Routledge, 2013); Tony Smith, America’s Mission: The United States and the Worldwide Struggle for Democracy—Expanded Edition (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2012); Gideon Rose, “Democracy Promotion and American Foreign Policy: A Review Essay,” International Security 25, no. 3 (2000): 186–203; Lindsey A. O’Rourke, Covert Regime Change: America’s Secret Cold War (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2018).

The United States overthrew elected governments with some frequency throughout the Cold War (see Iran, Guatemala, and Chile), has regularly made deals with autocrats (see Cold War Greece, Taiwan, South Korea, South Vietnam, and post-Cold War Saudi Arabia), and tolerated democratic backsliding among major allies (see Hungary, Poland, Pakistan, and Turkey).23On regime change, see Lindsey A. O’Rourke, “The Strategic Logic of Covert Regime Change: US-Backed Regime Change Campaigns during the Cold War,” Security Studies 29, no. 1 (January 1, 2020): 92–127, https://doi.org/10.1080/09636412.2020.1693620. For U.S. backing despite democratic backsliding, compare the record of democratic sliding detailed in Norman Eisen, Andrew Kenealy, Susan Corke, Torrey Taussig, and Alina Polyakova, The Democracy Playbook: Preventing and Reversing Democratic Backsliding (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, 2019) to contemporary U.S. statements of commitment to allies and partners. On support for autocracies, see among others Jeanne Kirkpatrick, “Dictatorships and Double Standards,” Commentary 68, no. 5 (1979); David Schmitz, Thank God They’re on Our Side: The United States and Right-Wing Dictatorships, 1921–1965 (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1999); Ben Rhodes, “Why No One Believes American Rhetoric about Democracy,” Atlantic, July 2022, https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2022/07/saudi-arabia-biden-visit/670468/. In the later case, some analysts have tried to explain U.S. backing for autocracy as a necessary step to ensure an eventual democratic transition. This is a good rationalization but seems more than a bit like putting lipstick on a pig given stated U.S. interests and the uncertainty of any democratic transition; see David Adesnik and Michael McFaul, “Engaging Autocratic Allies to Promote Democracy,” The Washington Quarterly 29, no. 2 (2006): 5–26. In short, Washington never made the defense of foreign democracy an interest per se; the question has been whether supporting a given country advances American interests. Insofar as a “liberal order” emerged due to American policy, it was despite U.S. ambivalence over backstopping other democracies as an end unto themselves.24For discussion of how competitive pressures influence U.S. interest in democracy—and not the other way around—during the Cold War, see Kyle Lascurettes, Orders of Exclusion: The Strategic Sources of Order in International Relations (Charlottsville, VA: University of Virginia, 2012). Asserting that the liberal order now requires the United States to defend Ukraine inverts the logic, ignoring the processes by which a “liberal order” developed and deepened.

Countries targeted for regime change by the U.S. during the Cold War

During the Cold War, strictures against intervention were often covertly violated by U.S. diplomats and spies. The great purpose of such intervention was usually to fight communism, not build democracy.

Of course, one might argue that the United States ought to make the defense of democracies a core interest lest democratic losses aggregate in the years ahead.25There is a potential logic here: if autocracy were linked to an alternative ideology (that is, way of organizing domestic society), then its spread might theoretically empower ideological fellow-travelers in the United States while undercutting the appeal of liberal democracy. If so, then combating the spread of this alternate ideology—of which autocracy would be one indicator—might be in the U.S. interest. For discussion along these lines, see Mark L. Haas, The Ideological Origins of Great Power Politics, 1789–1989 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2005). Still, autocracy is not itself an ideology and the underlying causal logic remains to be tested, leaving the policy prescription tendentious. Here, a different problem emerges: Ukraine is a poor fit for demonstrating an American commitment to this objective.26Tellingly, the Obama administration threatened to withhold a $1 billion loan guarantee to Ukraine due to Ukraine’s failure to address internal corruption. See U.S. Senate Committee on Appropriations, “Fact Check,” January 24, 2020, https://www.appropriations.senate.gov/news/minority/fact-check-president-trumps-false-claim-equating-his-illegal-ukraine-aid-freeze-with-president-obamas-lawful-legitimate-pauses-on-aid. Polite company may not comment on it, but Ukraine’s current democratic bona fides are questionable.27An argument can be made that Ukraine may further liberalize and democratize in the future. Backing a state on the possibility that it may liberalize in the future, however, would be a major change even to the idea that the U.S. should help other democracies; it’s a large gamble that, given the fits and stops that often accompany democratization, may well not pay off. Independent assessments by Freedom House, the Polity project, or the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) project consistently judge Ukraine as less than a full-fledged democracy—listed as an “anocracy” by Polity, for instance, and a “hybrid regime” with a 39 percent “democracy percentage” by Freedom House. Corruption, constrained press freedoms, questions over judicial integrity, and “the lack of rule of law” are all considered to be questionable. Nor have these scores improved over time. The V-Dem project, for example, shows Ukraine’s democracy scores moving within middle ranges since independence, while the Polity project shows Ukrainian democracy declining since 2006.28Author calculations. The intra-elite infighting and crackdowns on political opponents witnessed over much of the last decade (which may be reemerging as the intensity of the Russian invasion abates) suggests a similar trend.29On Ukraine divisions, see the reports from Freedom House over the last decade. For recent divides, see Miriam Berger and Konstiantyn Khudov, “As War Grinds On, Old Ukrainian Political Divisions are Re-Emerging,” Washington Post, August 3, 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2022/08/03/ukraine-political-divisions-zelensky-mayors/. In short, even if one argues that the fate of the liberal order rests on active U.S. support for liberal democracies, Ukraine today is a poor proving ground of that commitment.

Finally, arguments that failure to oppose Russia in Ukraine will undermine the norms and operating principles of the “liberal order” are equally problematic. As Patrick Porter, Paul Staniland, and others have shown, the liberal order was free neither from violence nor from violations of state sovereignty. On the contrary, it survived (and in some cases, relied upon) a large degree of state-led violence and challenges to others’ sovereignty in support of dubious objectives throughout its postwar history.30Patrick Porter, The False Promise of Liberal Order: Nostalgia, Delusion and the Rise of Trump (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2020); Robert Vitalis, White World Order, Black Power Politics: The Birth of American International Relations, (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2017). Misreading the “Liberal Order”: Why We Need New Thinking in American Foreign Policy,” Lawfare, July 29, 2018, https://www.lawfareblog.com/misreading-liberal-order-why-we-need-new-thinking-american-foreign-policy. It is thus hard to see how Russia’s deplorable behavior in Ukraine is somehow more injurious to a “liberal order” than the Vietnam or Iraq Wars, Israeli use of force in its “near-abroad,” or the Saudi campaign in Yemen, among others.

By the same token, the “liberal order” has evinced a remarkable capacity for tolerating a wide range of inter- and intra-state violence and other behaviors at odds with its presumed operating principles. Even a cursory glance at history reveals the trend, with the “liberal order” no more torn asunder by the American and allied reluctance to act in Bosnia until much of the bloodletting was over, than it was by the 2008 Russo-Georgian War. Seen in this light, the Russian invasion is not so much a threat to the “order” as a particularly thuggish manifestation of the sort of violence and violations that have long existed within the “order,” by a state many actors do not especially like. Again, we can and should lament the horrors visited upon Ukraine. However, claims that Russian aggression somehow overturns the principles upon which the “order” rests fall flat.

America’s Ukraine policy: a departure from U.S. grand strategy

Ultimately, none of the claimed U.S. interests in Ukraine offered amid the present debate withstand scrutiny. In response, proponents of U.S. do-more-ism might fall back to argue that core tenets of U.S. grand strategy writ large and policy toward Europe in particular mandate American involvement in Ukraine. In this view, the longstanding U.S. interest in preventing the emergence of a Eurasian regional hegemon and/or in building what then-President Bill Clinton termed a Europe “whole, free, and at peace” might require thwarting Russia by deepening support for Ukraine. Yet not only is neither issue at stake in Ukraine, but both the current thrust of U.S. policy and potential further U.S. involvement contradicts these goals in key ways.

The United States has long acted to prevent a regional hegemon from emerging in Eurasia.31This objective helped motivate U.S. intervention in the First and Second World Wars and gave much of the impetus to U.S. policy during the Cold War. As implied earlier in this paper, however, Russia is not poised to be a regional hegemon today, and it will not become one in the foreseeable future. It has an impressive nuclear arsenal and large military-industrial complex, but its economy is smaller than Italy’s; it occupies an unfavorable piece of real estate; has a history of antagonizing its neighbors in ways that can quickly spur balancing; and is beset with demographic problems. As its performance in Ukraine demonstrates, it also confronts enormous difficulties translating its latent power potential into competent and effective military forces, let alone creating favorable diplomatic conditions to increase its political reach. Likewise, it has already lost much of its best weaponry and thousands of its best soldiers in Ukraine, just as Western sanctions are likely to impair a quick recovery from the present conflict.32On this last point, proponents of the existing policy may retort that Russia has suffered in and over Ukraine partly due to Western/U.S. policies that might not have developed had the United States treated Ukraine as a lower-priority issue. This argument may carry some truth, but it does not change the overarching point that Russia is not a potential regional hegemon that merits major U.S. counterbalancing efforts. For one thing, and as elaborated below, even a Russian victory in Ukraine still leaves Russia far from regional hegemony. At the same time, many of Russia’s military problems seem driven as much by internal Russian problems—e.g., poor military doctrine, faulty intelligence, low morale—as by Ukrainian successes buoyed by Western policy. Proponents of the existing policy can therefore argue that Western policy has made an already weak Russian position even worse, but, even without the existing policy, Russia was not on the verge of regional dominance.

Moreover, other regional actors have more than enough raw capacity to resist it either alone or in combination.33German GDP, for example, is 2.5 times Russia’s. Data reported by the World Bank. Likewise, Romania, Poland, Hungary, Slovakia, and the Czech Republic together nearly equal Russian GDP and spend the equivalent of 60 percent of Russia’s entire defense budget. Given the quick and hard balancing against Russia’s invasion, they also seem to have the political will to resist Russian designs. And unlike the Soviet Union (the last hegemonic threat to Europe), which benefitted from a pliant Eastern Europe that allowed it to forward-deploy armies seemingly poised to reach the Atlantic Coast within weeks, Russian forces today are more than 1,000 miles farther east than their Soviet counterparts.34Thanks go to Emma Ashford for this point. Even if Russia had the forces available—and it won’t—there is significantly more territory for it to cross and time to mount a response than when Europe last faced a potential hegemonic bid.

Nor would a Russian victory in Ukraine change this situation. Even if all of Ukraine’s resources were added to Russia’s, its economy would still be smaller than Italy’s and its population would barely be that of France, Germany, and Poland combined. Russian forces would still be more than 400 miles farther east than their Cold War Soviet equivalents and would have to move across an unwelcoming Eastern Europe. In other words, whatever happens in Ukraine, Russia is not going to dominate the continent of Europe—it is and will remain a massively smaller geopolitical competitor than the Cold War-era Soviet Union. The United States may wish to prevent the rise of a Eurasian hegemon, and, thankfully, the structure of European politics has already solved this problem.

If anything, American policy in Ukraine may end up undermining the U.S. objective of preventing a Eurasian hegemon. The problem here is not Russia, but China. Due in no small part to the intensity of the U.S.-led response to Russia’s invasion, Russia has increasingly turned to China for economic aid, diplomatic support, and military assistance. This situation has rebounded to China’s advantage, with Beijing able to set favorable terms of trade with Moscow, increase market access for China’s own goods and services, and gain political leverage that may soon translate into Russian diplomatic backing for China’s own interests. The result complicates U.S. grand strategy at a time when the United States and its allies are seeking to slow Chinese economic growth and limit Beijing’s geopolitical reach.

On the military front, too, an open-ended commitment of additional U.S. forces in Europe—with current plans calling for additional ground forces, strike aircraft, naval vessels, and support elements that will bring U.S. force totals to roughly 100,000 personnel—means that resources that could otherwise be reallocated to competing with China will be unavailable.35Ben Wolfgang, “As U.S. Troops Reach 100k in Europe Questions Mount over Endgame, Long-term Effects,” Washington Times, June 26, 2022, https://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2022/jun/26/us-troops-reach-100k-europe-questions-mount-over-e/; Jen Judson, “Congress Wants More Troops in Europe as War in Ukraine Drags On,” Defense News, July 1, 2022, https://www.defensenews.com/land/2022/07/01/congress-wants-more-troops-in-europe-as-war-in-ukraine-drags-on/; Anna Mulrine Grobe, “What a US Military Base in Poland May Signal for NATO,” Christian Science Monitor, August 5, 2022, https://www.csmonitor.com/USA/Military/2022/0805/What-a-US-military-base-in-Poland-may-signal-for-NATO; Andrea Shalal, Inti Landauro, “Biden Bolsters Long-term U.S. Military Presence in Europe,” Reuters, June 29, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/us/biden-says-us-changing-force-posture-europe-based-threat-2022-06-29/; Jim Garamone, “Biden Announces Changes in U.S. Force Posture in Europe,” DoD News, June 29, 2022, https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/3078087/biden-announces-changes-in-us-force-posture-in-europe/. For sure, reinforcing Europe draws largely on land forces while competing with China primarily requires air and sea assets. Over the short-term, the United States may therefore be able to use its military to address both Russia and China. Still, many of the long-range strike and reconnaissance assets needed to bolster defenses against Russia are those useful for addressing a rising China, implying greater tradeoffs across the theaters than may be immediately apparent. Similarly, if China is truly the “pacing threat” driving U.S. strategy, then U.S. forces may eventually need to be fine-tuned qualitatively and quantitively for operations in Asia; building up against Russia makes such readjustment more difficult and raises the risk that U.S. strategy may be left under-resourced in key ways.36On China as “pacing threat,” see Jim Garamone, “Official Talks DoD Policy Role in Chinese Pacing Threat, Integrated Deterrence,” DoD News, June 2, 2021, https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/2641068/official-talks-dod-policy-role-in-chinese-pacing-threat-integrated-deterrence/. On the necessity and difficulty of reallocating resources as threats and priorities shift, see Aaron Friedberg, The Weary Titan: Britain and the Experience of Relative Decline, 1895–1905 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1988); Barry R. Posen, The Sources of Military Doctrine: France, Britain, and Germany Between the World Wars (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1984); Science Research Council (U.S.) Social, The Politics of Strategic Adjustment: Ideas, Institutions, and Interests (New York: Columbia University Press, 1999). Collectively, if hindering a Eurasian hegemon is a primary objective of U.S. grand strategy, then the U.S. response to the war in Ukraine may end up being anything but sound strategy.

As for building a Europe “whole, free, and at peace,” the sad reality is that American policy toward Ukraine underscores that this ambition was practically problematic from the start. Without conquering the continent under the American aegis and imposing democracy, crafting a Europe truly whole, free, and at peace required that no rivalries or conflicts between European states emerge while democracy and integration marched forward. From the start, this left American ambitions hostage to local developments outside the United States’ control: Should integration or democracy slow, or tensions erupt, the United States would have to select at most two of the three stated objectives.

The rise of Russo-Ukraine tensions from the mid-2010s highlights the tradeoff. Ukraine is relatively more free than Russia and many of its citizens desire greater integration with the rest of Europe. As U.S. diplomats and intelligence analysts repeatedly warned, however, supporting Ukraine’s integration aspirations risked provoking a crisis with Russia and drawing a new dividing line in Eastern Europe.37William Burns, U.S. Department of State, https://carnegieendowment.org/pdf/back-channel/2008EmailtoRice1.pdf; https://carnegieendowment.org/pdf/back-channel/2006Moscow6759.pdf. Conversely, the United States could have prioritized peace, stability, and avoiding dividing lines across Eastern Europe by conciliating Moscow, but this was only viable if Washington accepted limits on Ukraine’s Western integration (and likely tolerated some degree of Russian influence over Ukrainian politics). As U.S. choices since 2014 indicate, policymakers dealing with this tradeoff took steps that, even while not the direct cause of the present war, undermined the “at peace” leg of the triangle.38Put another way, Russia bears responsibility for the decision to invade Ukraine and launch a war in February 2022 even if U.S. policy contributed to diplomatic and strategic conditions that made a crisis over Ukraine a possibility. “Whole, free, and at peace” was a laudable objective. Still, it was an ambition that was never truly in Washington’s power to produce, and it has now been relegated to the background of U.S. policy.

American interest and the Ukraine war: the case for course correction

If claimed U.S. interests in Ukraine are wanting and current U.S. policy cannot be justified in light of U.S. grand strategic precepts, should the United States care at all about the Russian invasion of Ukraine? If so, what might a revised U.S. policy entail?

Strategy requires setting priorities and allocating relatively scarce resources to service those objectives. For much of the post-Cold War era, however, unipolarity meant that the United States seemingly did not have set clear priorities or worry much about resources. With power so heavily skewed in America’s favor, policymakers could pursue such disparate objectives as NATO enlargement, regime change in the Middle East, and hedging against China without worrying about where the resources would come from or how the parts fit together. The situation is very different now and will likely become more difficult. A combination of domestic demands and renewed geopolitical competition—particularly in Asia, where China is the most likely candidate to seek Eurasian hegemony—is compelling policymakers to re-evaluate U.S. priorities and consider from where the requisite resources will come. Compared to the Cold War and immediate post-Cold War era, Europe is being downgraded.

Viewed in this light, American interests in Ukraine are limited. First and foremost, the United States has a strong interest in avoiding escalation with Russia over Ukraine whether by virtue of the United States’ direct involvement in the conflict or—more likely—due to the conflict spilling beyond Ukraine’s borders. The focus ought to be on reducing the chance that the United States is pulled into a broader confrontation with Russia that might ultimately involve a clash of arms, up to and including a possible nuclear crisis or exchange. Second, the United States maintains an interest in avoiding such a collapse of U.S.-Russian relations (1) that any future engagement with Russia on issues of mutual concern (e.g., arms control, counter-terrorism, climate change) becomes impossible and (2) that Moscow, as Henry Kissinger cautions, is driven to seek “a permanent alliance elsewhere”—that is, with China.39Lukas Bester, “Kissinger: These Are the Main Geopolitical Challenges Facing the World Right Now,” World Economic Forum, May 23, 2022, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/05/kissinger-these-are-the-main-geopolitical-challenges-facing-the-world-right-now/; Laura Secor, “Henry Kissinger Is Worried About ‘Disequilibrium’,” Wall Street Journal, August 12, 2022, https://www.wsj.com/articles/henry-kissinger-is-worried-about-disequilibrium-11660325251; Timothy Bella, “Kissinger Says Ukraine Should Cede Territory to Russia to End War,” Washington Post, May 24, 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2022/05/24/henry-kissinger-ukraine-russia-territory-davos/. These outcomes would complicate the United States’ strategic map and exacerbate the already difficult adjustments underway in U.S. grand strategy as the unipolar era comes to an end.40Skeptics might argue that a tight Russo-Chinese axis is inevitable regardless of the policies pursued by the United States, such that the U.S. ought not to worry much about driving Russia into China’s arms. This line of reasoning is belied by the United States’ own efforts to warn China against aiding Russia in the early days of the conflict and reports throughout the spring and summer of 2022 that Russia was increasingly dependent on Chinese technology, diplomatic cover, and markets. Even if warm political relations between Moscow and Beijing are likely, U.S. policy influences key aspects of Russian-Chinese ties—just as it remains in the U.S. interest to limit the scope, depth, and intensity of this relationship. See “Russia Turns to China for Microchips for In-demand Domestic Bank Cards,” Reuters, April 5, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/technology/russia-turns-china-microchips-in-demand-domestic-bank-cards-2022-04-05/; Ishaan Tharoor, “Russia Becomes China’s ‘Junior Partner’,” Washington Post, August 12, 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2022/08/12/china-russia-power-imbalance-putin-xi-junior-partner/; Alexander Gabuev, “China’s New Vassal,” Foreign Affairs, August 9, 2022, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/china/chinas-new-vassal; “Russia-Ukraine War: US Warns China Against Aiding Moscow,” Al Jazeera, March 14, 2022, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/3/14/us-warns-china-against-coming-to-russia-aid-in-ukraine. For a contrasting take treating a tight Russo-Chinese axis as immutable, see in Hal Brands, “Opposing China Means Defeating Russia,” Foreign Policy, April 5, 2022, https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/04/05/china-russia-war-ukraine/.

Third, it is important to limit the economic fallout of the war—in terms of both direct harm and resulting from the sanctions imposed on Russia—at a time when the consequences of the Covid pandemic continue to cloud the global economic outlook. Finally, the United States has at least some interest in sustaining the already-favorable European balance of power as an insurance policy against the risk that Russia—or some other state—concludes that aggression might pay. Note that this last interest is not about teaching Russia (or others) a lesson by causing harm as the current policy conversation has it, but rather about reducing opportunities for Russian aggrandizement going forward.

Servicing these more limited yet important objectives requires adjusting U.S. policy in several important ways. In practice, limiting the risk of escalation, mitigating the economic fallout, and avoiding an irrevocable break with Moscow implies bringing the conflict to a timely end without drawing the United States further into the contest.41Against this, some may argue that the conflict is at a natural equilibrium and the U.S. can at least live with the war continuing indefinitely. The problem is that the war may not remain at stalemate or do so at acceptable cost to the parties. Ultimately, the longer the conflict continues, the greater the likelihood one or both sides may take gambles to break the stalemate by, for example, risky military operations or drawing in new participants; the German decision to declare unrestricted submarine warfare amid the stalemate of World War I—an act that helped pull the United States into the conflict—is illustrative of the risk. Escalation and/or spillover under such circumstances cannot be ruled out. Given the battlefield distribution of power and Russia’s apparent willingness to tolerate exceedingly large costs, this means pressuring Kyiv to negotiate with Russia while engaging Moscow to foster a diplomatic deal to end the conflict.42Recent Ukrainian battlefield successes underscore the point. As of this writing (mid-September 2022), Ukraine has apparently mounted a successful counterattack in the north that has retaken a sizable portion of Russian-held territory. Although a notable Ukrainian achievement, the strategic picture remains complicated as (a) Russia retains large parts of Ukrainian territory and has the capacity to escalate the conflict further (e.g., by mobilizing its reserves), and (b) it is unclear if Ukraine can sustain or replicate these successes. Ukraine’s counterattack may have thus improved its leverage at the bargaining table without changing the strategic outlook—indeed, by giving Russia an incentive to escalate, it may only have prolonged the contest. For Ukrainian statements suggesting recognition of its own limitations, see Pavel Polityuk and Tom Balmforth, “Ukraine Hails Snowballing Offensive, Blames Russia for Blackouts,” Reuters, September 11, 2022; on Russian resolve, see Mark Trevelyan, “Russia Shrugs Off Retreat in Northeast Ukraine as Putin Focuses on Economy,” Reuters, September 12, 2022. Here, the United States would have to turn away from its stated opposition to compelling Kyiv to the negotiating table, potentially by manipulating its assistance to Ukraine in order to create positive and negative incentives to this end. By the same token, the United States would also need to find a way of reopening dialogue with Moscow while giving Russia sufficient inducements—potentially in the form of reduced sanctions—and potential penalties to end the conflict.43Admittedly, negotiations may not succeed in the short-term; Russia may want more than Ukraine is willing to concede, just as Ukrainian leaders may believe they can turn the military tide against Russia and/or count on Western pressure to induce Russia to sue for peace. Still, if America pressed for a negotiated peace, Russian gains continue to slow, and Ukrainian losses—particularly without a battlefield breakthrough—and pain mount, a negotiated settlement might not be impossible. Similarly, see Barry R. Posen, “Ukraine’s Implausible Theories of Victory,” Foreign Affairs, July 8, 2022, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/ukraine/2022-07-08/ukraines-implausible-theories-victory. For potential limits on a deal, see the details on spring 2022 Ukraine-Russia negotiations reported in Fiona Hill, Angela Stent, “The World Putin Wants,” Foreign Affairs, September/October 2022, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/russian-federation/world-putin-wants-fiona-hill-angela-stent.

Critics may charge that this course sells out Ukraine—particularly at a time when Ukrainian counterattacks have reversed some Russian conquests—rewards Russian aggression, and does nothing to prevent Russia from biding its time before re-invading Ukraine. These charges may be partly true.44In principle, Ukraine could benefit even from a negotiated settlement that proved temporary if it used the opportunity to rearm, make good wartime losses, and maximize efforts to deter or defeat Russia. A pause of several years might be in Kyiv’s interest. Thanks go to Emma Ashford for suggesting this point. Still, two points are important. On one level, again, the United States has minimal interests in what happens in or to Ukraine per se. If Ukraine were central to the balance of power or the liberal order, this would change—but it isn’t. Accordingly, as tragic as it would be to witness future Russian aggression against Ukraine, it would be a still greater tragedy if the United States ends up risking—even probabilistically—conflict with Russia for no strategic purpose or facilitates the rise of a true Eurasian hegemon by misallocating its time and resources.45Ukraine’s recent battlefield successes underscore the risk. Having suffered at least an operational setback, the Russian government now faces incentives to escalate and/or intensify the conflict (e.g., through additional attacks on infrastructure or civilian targets) in order to restore its position or otherwise gamble for resurrection. Under these circumstances, it is not implausible to imagine a Russian gambit that increases the odds of a direct U.S.-Russian confrontation, particularly given U.S. aid and intelligence support to Ukraine’s military efforts thus far and calls to facilitate more Ukrainian successes in the future. Again, a type of 1917 scenario—where German leaders gambled that unrestricted submarine warfare to hinder the Allied war effort was worth the risk of drawing the United States into World War One—cannot be ruled out. Perversely, Ukraine’s recent successes may therefore only have reinforced the case for the United States seeking a negotiated settlement in support of its interests.

By the same token, this would hardly be the first time when a reassessment of U.S. interests and priorities led the U.S. to compel partners and allies into making harsh sacrifices while dealing with real or potential aggressors. Similar policies, for instance, were behind the U.S. push to end the Vietnam War, to divide Cold War Germany, and to foster different Arab-Israeli and Palestinian-Israeli deals. Not all these contests ended with the United States’ preferred party “winning” at the diplomatic table (or, in South Vietnam’s case, surviving). Nevertheless, just as the United States saw its own interests preserved in these prior episodes, so too may its fairly limited interests in Ukraine be advanced by deploying a similar playbook.

As for sustaining a favorable distribution of power, the United States ought to encourage European efforts at arming and allying independent of the United States. To date, U.S. policymakers have been almost giddy at the prospect of “revitalizing NATO” by bolstering European defense spending, having European states focus their newfound military interests into the alliance, seeing the alliance take on new allies, and underlining the American commitment to transatlantic security. This reaction is understandable given longstanding concerns with allied cheap-riding, NATO’s mission drift, and the future of American “leadership” in Europe. Insofar as U.S. attention is shifting toward Asia, however, it also reinforces European defense dependence on the United States as the security guarantor of first and last resort within NATO—a situation that may prove wanting over the long term and may in any case be a liability to the United States’ rebalancing efforts. A sounder course would be to redirect Europe’s laudable newfound interest in military affairs into greater strategic autonomy and improvements to European states’ military toolkits. Given the already-favorable distribution of power, only moderate investments are likely needed, with logistics, reconnaissance assets, command and control mechanisms, and smart munitions as priority areas.46Barry R. Posen, “Europe Can Defend Itself,” Survival 62, no. 6 (2020): 7–34, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00396338.2020.1851080. Regardless, the desired course is to see prudent and focused European efforts that reinforce the already-attractive distribution of power outside the current U.S.-supplied framework.

Conclusion

Ultimately, the course and conduct of American policy in response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine has been a-strategic. To be sure, some kind of American reaction to Moscow’s attack was warranted; diplomatic condemnation of Moscow’s invasion, strong sanctions on Russia, and an initial arms delivery to prevent an easy Russian success, for example, made sense.47In light of American and allied investments in the Ukrainian military since 2014 and, in any case, logistics delays in delivering the armaments announced in 2022, it seems plausible that a moderately-sized initial arms delivery would have sufficed to blunt Russia’s offensive and ensure Moscow paid dearly for its choices. Nevertheless, policymakers have rushed to back Kyiv to a firm and potentially dangerous degree based on vague assertions of Ukraine’s importance in arresting future aggression and preserving the “liberal international order,” with little evaluation of whether the claims operate—or are as important—as implied.48Related dangers come from overstating the degree of American support for Ukraine and/or Ukrainian perceptions of unvarnished American backing. For different reasons, both risk spurring Ukrainian over-optimism; the former may also reinforce Russian narratives of a hostile West, encourage Russian risk-taking, and complicate any diplomatic solution. Future research on these risks is warranted. Along the way, evaluation of whether the America response is proportionate to the situation at hand or services broader American interests has been lost. Sober analysis has been lost—no small problem given the inherent risks of playing in the backyard of a nuclear-armed power party to a war at a time of shifting U.S. priorities and new demands upon U.S. resources.

Stepping back, a strong case can be made instead that U.S. interests in Ukraine are significantly different and more muted than what some pundits and policymakers have so far claimed. Those interests that are in play, meanwhile, argue strongly for the United States quickly bringing about a negotiated settlement to the conflict, potentially by simultaneously pressuring and engaging both Kyiv and Moscow. Just as policymakers in years past turned away from involvement in other episodes where emotions ran high but interests were limited—think of Hungary in 1956 or South Vietnam in 1975—or where opportunity costs were too large to ignore—deprioritizing the Republic of China in favor of the People’s Republic of China come to mind—so too is a course correction to U.S. policy in order. The result might be at odds with the conventional wisdom, but it would be far from a tragedy for any number of American interests.

Endnotes

- 1Thanks go to Emma Ashford, Benjamin H. Friedman, Lindsey O’Rourke, Christopher Preble, William Ruger, and Stephen Walt for comments on prior drafts.

- 2“Amb. Michael McFaul: U.S. Has ‘a Major Strategic Interest to Help the Ukrainians Win the Battle of Donbas’,” Yahoo, April 20, 2022, https://www.yahoo.com/now/amb-michael-mcfaul-u-major-183111659.html; Atlantic Council, “Why Ukraine’s Success is in the U.S. National Interest,” YouTube Video, February 4, 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K6OUQe_Za18.

- 3See also “Russia’s War in Ukraine: How Does it End?” Council on Foreign Relations, May 31, 2022, https://www.cfr.org/event/russias-war-ukraine-how-does-it-end. See also Alina Polyakova, Daniel Fried, “Putin’s Long Game in Ukraine,” Foreign Affairs, February 23, 2022, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/ukraine/2022-02-23/putins-long-game-ukraine.

- 4Natasha Bertrand, Kylie Atwood, Kevin Liptak, Alex Marquardt, “Austin’s Assertion that US Wants to ‘Weaken’ Russia Underlines Biden Strategy Shift,” CNN, April 26, 2022, https://www.cnn.com/2022/04/25/politics/biden-administration-russia-strategy/index.html.

- 5Joseph R. Biden Jr., “President Biden: What America Will and Will Not Do in Ukraine,” New York Times, May 31, 2022, quoted in Robin Wright, “Ukraine is Now America’s War, Too,” New Yorker, May 1, 2022, https://www.newyorker.com/news/daily-comment/ukraine-is-now-americas-war-too. See also Marc A. Thiessen, “If Putin is Allowed to Invade Ukraine, America’s Credibility Would Lie in Tatters,” Washington Post, February 8, 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2022/02/08/ukraine-russia-war-united-states-china/.

- 6Michael Crowley, “Biden’s Stand on Ukraine Is a Wider Test of U.S. Credibility Abroad,” New York Times, December 16, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/12/16/us/politics/biden-russia-ukraine.html. See also https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/09/01/china-taiwan-ukraine-war-lessons/?tpcc=recirc_latest062921.

- 7Antony Blinken, “Secretary Blinken’s Remarks,” U.S. Department of State, March 4, 2022, https://www.state.gov/secretary-antony-j-blinken-at-a-press-availability-15/. Similarly, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Gen. Mark Milley claims that if Russia’s invasion “is left to stand, if there is no answer to this aggression, if Russia gets away with this cost-free, then so goes the so-called international order” without explaining how or why this is the case.

- 8Joseph R. Biden Jr., “Remarks by President Biden on the United Efforts of the Free World to Support the People of Ukraine,” The White House, March 26, 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/speeches-remarks/2022/03/26/remarks-by-president-biden-on-the-united-efforts-of-the-free-world-to-support-the-people-of-ukraine/. See also Steven Feldstein, “Ukraine Won’t Save Democracy,” Foreign Affairs, July 26, 2022, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/world/ukraine-wont-save-democracy; Ishaan Tharoor, “The War in Ukraine Underscores a Moment of Democratic Crisis,” Washington Post, April 20, 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2022/04/20/democratic-decline-authoritarianism-ukaine/.

- 9Kimberly Atkins Stohr, “As War Drags on in Ukraine, Is It Time to Talk Compromise?” WBUR, June 21, 2022, https://www.wbur.org/onpoint/2022/06/21/ukraine-russia-america-conflict-war-over-applebaum. Also Richard Fontaine, “Why Russia Must Fail in Ukraine,” CNAS, July 6, 2022, https://www.cnas.org/publications/commentary/why-russia-must-fail-in-ukraine; Ivo H. Daalder, James M. Lindsay, “Last Best Hope,” Foreign Affairs, July/August 2022, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/world/2022-06-21/last-best-hope-better-world-order-west; Damien Cave, “The War in Ukraine Holds a Warning for the World Order,” New York Times, March 4, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/04/world/ukraine-russia-war-authoritarianism.html.

- 10Author calculations based on 2021 Federal Budget. See Kelley Griffin, “The Impact of Russia Sanctions on US States,” NCSL, February 28, 2022, https://www.ncsl.org/research/fiscal-policy/the-impact-of-russia-sanctions-on-us-states-magazine2022.aspx; Ira Kalish, “How Sanctions Impact Russia and the Global Economy,” Deloitte, March 15, 2022, https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/economy/global-economic-impact-of-sanctions-on-russia.html; Rebecca M. Nelson, “Russia’s War on Ukraine: The Economic Impact of Sanctions,” Congressional Research Service, May 3, 2022, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF12092#:~:text=Sanctions%20that%20isolate%20Russia%20are,slowdown%20in%20global%20economic%20growth. Illustrating the point, President Biden and other policymakers have acknowledged the economic impact of the American response for U.S. citizens. See Nancy Cook, “Biden Says Inflation Is ‘Hurting’ US Families, Blames Pandemic,” Bloomberg, May 10, 2022, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-05-10/biden-says-inflation-hurting-u-s-families-blames-pandemic; “Biden Says Defending Ukraine Could Cause U.S. Economy Pain,” Bluefield Daily Telegraph, February 15, 2022, https://www.bdtonline.com/news/biden-says-defending-ukraine-could-cause-u-s-economy-pain/article_af47a684-8ea2-11ec-bef8-abb386de921d.html. The combined U.S. Labor, Commerce, and Transport departments budgets totaled $43.8 billion in 2021. U.S. aid to Ukraine from January to July 2022 totaled 42.615 billion Euros, or approximately $42.6 billion at current exchange rates. Author calculations from “Budget of the U.S. Government, Fiscal Year 2022,” U.S. Office of Management and Budget, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/budget_fy22.pdf.

- 11For illustration, see Andrew Kydd, “Will NATO Fight Russia Over Ukraine? The Stability-Instability Paradox Says No,” Political Violence At A Glance, March 24, 2022, https://politicalviolenceataglance.org/2022/03/24/will-nato-fight-russia-over-ukraine-the-stability-instability-paradox-says-no/; Andrew Kydd (@AHKydd), Twitter Post, June 11, 2022, https://twitter.com/AHKydd/status/1535810787956097024; Dan Altman, “The West Worries Too Much About Escalation in Ukraine,” Foreign Affairs, July 12, 2022, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/ukraine/2022-07-12/west-worries-too-much-about-escalation-ukraine.

- 12Jack L. Snyder, Myths of Empire: Domestic Politics and International Ambition (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1991); Randall L. Schweller, “Tripolarity and the Second World War,” International Studies Quarterly 37, no. 1 (1993): 73–103, https://doi.org/10.2307/2600832.

- 13Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War, trans. Rex Warner and M. I Finley (Harmondsworth, U.K.: Penguin Books, 1972); Edward V. Gulick, Europe’s Classical Balance of Power: A Case History of the Theory and Practice of One of the Great Concepts of European Statecraft (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1955); Hans J Morgenthau, Politics Among Nations: The Struggle for Power and Peace, 2nd ed. (New York: Knopf, 1954); Kenneth N. Waltz, Theory of International Politics (Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1979); Karl W. Deutsch and J. David Singer, “Multipolar Power Systems and International Stability,” World Politics 16, no. 3 (April 1964): 390–406; Dale C. Copeland, The Origins of Major War (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2000).

- 14Stephen M. Walt, The Origins of Alliances (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1987); Eric J. Labs, “Do Weak States Bandwagon?” Security Studies 1, no. 3 (1992): 383–416; Robert Jervis and Jack L Snyder, eds., Dominoes and Bandwagons: Strategic Beliefs and Great Power Competition in the Eurasian Rimland (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991).

- 15For Biden’s comments and commitment, see Ashley Parker and Emily Rauhala, “Biden and NATO Send Russia Defiant Message,” Washington Post, June 29, 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2022/06/29/biden-nato-defiant-russia/. Illustrating the quick reaction to Russian moves, NATO’s newly revised Strategic Concept declared Russia, “the most significant and direct threat to Allies’ security and to peace and stability in the Euro-Atlantic area.” Likewise, allies have begun deploying limited numbers of additional forces along NATO’s eastern flank—with further increases possible—and boosted defense spending. For details, see Robbie Gramer, “Putin’s Invasion Has Turbocharged NATO Defense Spending,” Foreign Policy, June 30, 2022, https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/06/30/nato-defense-spending-putin-ukraine-war/; “NATO Plans Huge Upgrade of Rapid Reaction Force in ‘Era of Strategic Competition’,” France 24, June 27, 2022, https://www.france24.com/en/europe/20220627-nato-plans-huge-upgrade-of-rapid-reaction-force-in-era-of-strategic-competition; Matt Murphy, “NATO Plans Huge Upgrade in Rapid Reaction Force,” BBC, June 27, 2022, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-61954516; “Fact Sheet-U.S. Defense Contributions to Europe,” U.S. Department of Defense, June 29, 2022, https://www.defense.gov/News/Releases/Release/Article/3078056/fact-sheet-us-defense-contributions-to-europe/; “Madrid Summit Declaration,” NATO, June 29, 2022, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_196951.htm. Public opinion within NATO has also noticeably moved against Russia since the invasion; see Tobias Bunde, Tom Lubbock, “How United is the West on Russia?” Washington Post, July 5, 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2022/07/05/nato-russia-putin-threat-opinion-surveys-ukraine-invasion/.

- 16Jill Lawless, Joseph Wilson, Sylvie Corbet, “NATO Vows to Guard ‘Every Inch of Territory’ as Russia Fumes,” AP News, June 30, 2022, https://apnews.com/article/russia-ukraine-nato-putin-madrid-9b249117b645e461f09cd0b4cb4afc02.

- 17The scope of Russian losses in the present conflict also leaves it debatable whether future aggression in Europe is even practical, particularly given the likelihood of a major European rearmament effort.

- 18Stephen M. Walt, “Will Teaching Aggressors a Lesson Deter Future Wars?” Foreign Policy, June 2, 2022, https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/06/02/will-teaching-aggressors-a-lesson-deter-future-wars/. Note that arguing other states are unlikely to be directly influenced by efforts to punish Russian aggression is distinct from the above claim that Russia may be sobered by its own recent experience.

- 19John J. Mearsheimer, Conventional Deterrence (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1983); Copeland, Origins; Jonathan Mercer, Reputation and International Politics (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2010); Daryl G. Press, Calculating Credibility: How Leaders Assess Military Threats (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2005). For a helpful discussion of recent research and analytic distinctions bearing on the topic, see Joshua D. Kertzer, “American Credibility After Afghanistan,” Foreign Affairs, September 2, 2021, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/afghanistan/2021-09-02/american-credibility-after-afghanistan.

- 20For illustration, see John A. Thompson, A Sense of Power: The Roots of America’s Global Role (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2015); Nicholas John Spykman, America’s Strategy in World Politics: The United States and the Balance of Power (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1942); Melvyn Leffler, A Preponderance of Power: National Security, the Truman Administration, and the Cold War (Redwood City, CA: Stanford University Press, 1992); Marc Trachtenberg, A Constructed Peace: The Making of the European Settlement, 1945–1963 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1999).

- 21A third objection—that states cannot credibly signal their future intentions at all—is also possible. This logic would suggest that acting in Ukraine as a deterrent to aggression more generally is simply not feasible as others will discount the implications of U.S. policy in Ukraine for any and all future scenarios (presumably falling back to contextual judgments of capability and interest). See Sebastian Rosato, Intentions in Great Power Politics: Uncertainty and the Roots of Conflict (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2021).

- 22Michael Cox, Timothy J. Lynch, and Nicolas Bouchet, eds., US Foreign Policy and Democracy Promotion: From Theodore Roosevelt to Barack Obama (New York: Routledge, 2013); Tony Smith, America’s Mission: The United States and the Worldwide Struggle for Democracy—Expanded Edition (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2012); Gideon Rose, “Democracy Promotion and American Foreign Policy: A Review Essay,” International Security 25, no. 3 (2000): 186–203; Lindsey A. O’Rourke, Covert Regime Change: America’s Secret Cold War (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2018).