Key points

- The U.S. has a goal to avoid a Chinese invasion of Taiwan, but the overriding U.S. interest is to avoid a ruinous war with China. The imperative to avoid a conflict with China should take priority for U.S. leaders.

- Proposals to deter China by bolstering U.S. military deployments in the Western Pacific are unlikely to succeed and fraught with danger. China has advantages in terms of geographical proximity to Taiwan and superior commitment to resolving the issue on favorable terms. The United States should not commit to fighting a great-power war at a time of China’s choosing.

- The Taiwanese obviously have the strongest interest in deterring a Chinese invasion of their island. Regional powers such as Japan, South Korea, the Philippines, and Australia have the next-strongest interests in preserving stability in East Asia. These actors should do the heavy lifting in deterring China.

- The U.S. should encourage Taiwan and other regional actors to develop their own means of deterring a Chinese invasion. Working with others, Taiwan has the capacity to inflict severe costs upon Beijing in the event of an armed attack. If calibrated correctly, Taiwan and others might convince Beijing that the various costs of invasion—economic sanctions, opprobrium, military balancing—outweigh the benefits and thus deter China from invading.

- America’s role should be to support Taiwanese-led efforts to deter China while working to convince all sides that the status quo is sustainable and the U.S. remains committed to its longstanding One China policy. This is the best chance of preventing a war in the Taiwan Strait.

Deterring China

How can China be deterred from invading Taiwan? In simple terms, China’s leaders must be made to expect that the costs of attempting a conquest of the island would outweigh the benefits. In other words, someone—whether Taiwan, the United States, regional powers, or a combination of these actors—must threaten China with such severe consequences that achieving national unification by force becomes less attractive to Beijing than maintaining the status quo. This is a tall order, of course, because China’s leaders place such a high value on capturing Taiwan.1As Mike Sweeney has put it, “Any battle over Taiwan will not just be a question of territorial aggression but a fight over the core conception of modern China’s soul.” See Mike Sweeney, “Why a Taiwan Conflict Could Go Nuclear,” Defense Priorities, March 4, 2021, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/why-a-taiwan-conflict-could-go-nuclear.

The effectiveness of any deterrent is a function of its severity (the seriousness of the threat being issued) and credibility (the likelihood of the threat being carried out). This means that deterrence across the Taiwan Strait will be strongest if China expects to face severe costs for invading Taiwan and is convinced these costs have a high probability of being meted out. Deterrence is weakest if China expects to incur a manageable level of cost or if it doubts the willingness of nations to follow through on their most severe threats.

In the past, the United States was able to deter China by threatening a conventional military response. This was certainly true in the 1950s when the United States enjoyed clear military superiority over China. Between 1955 and 1980, the United States remained treaty-bound to assist in the defense of Taiwan. Especially at the beginning of this period, China both feared a U.S. military intervention and believed that such an intervention might happen.

But the world of today is much different from that of the early Cold War. Most important, the conventional balance of power across the Taiwan Strait has shifted in China’s favor, meaning U.S. threats to wage a conventional war against China have less credibility. The idea the United States would risk nuclear war over Taiwan has always been questionable, especially since Beijing developed a “true, reliable second-strike capability” in the 1990s.2Liping Xia, “China’s Nuclear Doctrine: Debates and Evolution,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, June 30, 2016, https://carnegieendowment.org/2016/06/30/china-s-nuclear-doctrine-debates-and-evolution-pub-63967. Is Taiwan strategically important enough to justify the sacrifice of American lives to defend it? The point is not that the United States is certain to stand aside if China invades Taiwan, but that both Beijing and Taipei have serious reasons to doubt the strength of America’s commitments.3In March 2022, an opinion poll by the Taiwanese Public Opinion Foundation found that 55.9 percent of respondents doubted that the United States would intervene militarily on Taiwan’s behalf. See John Feng, “Taiwan Losing Faith in U.S. Rescue if China Invades—Poll,” Newsweek, March 23, 2022, https://www.newsweek.com/taiwan-public-opinion-poll-us-military-response-china-invasion-1690831.

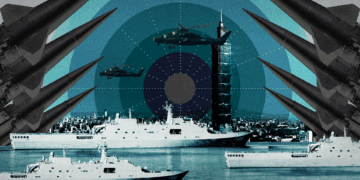

Countries in the Indo-Pacific with more than 100 U.S. military personnel

U.S. military deployments in the Indo-Pacific would be vulnerable in the event of a war with China, and their existence disincentivizes regional powers from taking on the burden of deterring China.

How can states bolster the credibility of their deterrents? One way is to “sink costs” toward the threat being made in hopes that such actions will be interpreted as a costly signal of future intentions.4James M. Fearon, “Signaling Foreign Policy Interests: Tying Hands Versus Sinking Costs,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 41, no. 1 (1997): 68–90. This might take the form of a costly military buildup, for example. Another option is to engage in “hands-tying”— the deliberate assumption of costs that will be borne in the event of a threat not being carried out. Thomas Schelling was one of the first scholars to speculate that deterrers might try to use domestic politics as leverage in international negotiations, especially as a means to convey credible resolve.5Thomas C. Schelling, The Strategy of Conflict (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1960), 28–29, cited in Helen V. Milner and Peter B. Rosdendorff, “Domestic Politics and International Trade Negotiations: Elections and Divided Government as Constraints on Trade Liberalization,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 41, no. 1 (1997): 117–146. See also Thomas C. Schelling, Arms and Influence (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1966). Others have since expanded upon the ways that leaders might manipulate their domestic environment to make it more likely that they follow through on an intended course of action.6Fearon, “Signaling Foreign Policy Interests.”

However, the United States faces challenges when it comes to bolstering the credibility of its threats to fight China over Taiwan. Not only is the United States trying to engage in the difficult task of “extended deterrence” (when one country tries to deter an aggressor from attacking a third party), but it is also doing so against a nuclear-armed adversary that has larger interests at stake and therefore more political will to fight. Simply put, it will be enormously difficult for U.S. leaders to convince China they are willing to risk a war over Taiwan that might turn nuclear.7Keith B. Payne, “The Taiwan Question: How to Think About Deterrence Now,” National Institute for Public Policy, November 15, 2021, https://nipp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/IS-509.pdf. See also Lyle Goldstein, “Raising the Minimum: Explaining China’s Nuclear Buildup,” Defense Priorities, April 5, 2022, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/raising-the-minimum-explaining-chinas-nuclear-buildup. This is especially true in light of President Biden’s unambiguous refusal to commit U.S. troops to Ukraine because of the looming threat of nuclear war with Russia.

The task of extended deterrence is especially tortuous in the case of Taiwan because the island’s contested political status and the U.S. policy of strategic ambiguity prevents the United States from taking even elementary steps to bolster the credibility of its deterrent. For example, the United States cannot sign a mutual defense pact with Taiwan (a form of hands-tying) because it does not recognize Taiwan as a sovereign state. Nor can the United States openly deploy conventional or nuclear forces to Taiwan (sunk costs). Such moves would not only be akin to a guarantee to defend Taiwan, a radical departure from current policy, but would also be far more likely to provoke a Chinese attack rather than deter one. Chinese leaders would likely perceive any U.S. deployments to Taiwan as an attempt to foreclose even peaceful unification between the two sides of the Strait.

Some scholars frame the erosion of U.S. credibility as a problem for the United States to fix. As Michèle Flournoy has written:

If Beijing believes it could thwart an effective U.S. military response, it might be tempted to use force against Taiwan or to seize additional disputed territories in the South China Sea. Such a crisis could quickly escalate into a military conflict between two nuclear-armed powers. Hence the imperative of ensuring that Chinese military action would be unsuccessful and costly—and that Chinese leaders are convinced of that fact.8Michèle Flournoy, “America’s Military Risks Losing Its Edge,” Foreign Affairs 100, no. 3 (2021): 76–90. See also Richard Haass and David Sacks, “American Support for Taiwan Must Be Unambiguous: To Keep the Peace, Make Clear to China That Force Won’t Stand,” Foreign Affairs, September 2, 2020, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/american-support-taiwan-must-be-unambiguous; and Richard Haass and David Sacks, “The Growing Danger of U.S. Ambiguity on Taiwan: Biden Must Make America’s Commitment Clear to China—and the World,” Foreign Affairs, December 13, 2021, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/china/2021-12-13/growing-danger-us-ambiguity-taiwan.

From this view, it is a grave danger that China has cause to doubt America’s intentions to intercede militarily on Taiwan’s behalf. There is no option but for Washington to convince Beijing that an invasion of Taiwan would truly result in conflict between the world’s two largest militaries. However, persuading Chinese leaders that the United States will fight a war over Taiwan is easier said than done. Decisionmakers in Beijing have powerful reasons to doubt that Taiwanese security is a core concern of the United States. Given that states only fight wars—especially those that might “go nuclear”—when they have vital interests at stake, it follows that U.S. threats of military force will always be viewed with skepticism in Beijing. Neither bluff nor bluster will alter this basic calculation about U.S. interests, intentions, and likely responses.9Daryl Press calls this the “Current Calculus theory” of credibility. See Daryl G. Press, Calculating Credibility: How Leaders Assess Military Threats (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2005), 8–9.

Before devising any new schemes to make World War III sound like a credible threat, then, there is an alternative approach U.S. leaders should consider: instead of it falling to the United States to deter China from invading Taiwan, other actors could assume the burden of deterrence. After all, the most credible threats are made by those who have the most at stake. As Michael Mazarr writes: “An aggressor can almost always be certain a state will fight to defend itself, but it may doubt that a defender will fulfill a pledge to defend a third party.”10Michael J. Mazarr, Understanding Deterrence (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2018), 3. In the case of Taiwan, this means Taiwanese threats against China will always stand a higher chance of being taken seriously by Beijing than comparable threats made by any other power, including the United States.11On the greater (“inherent”) credibility of threats made in self-defense as opposed to those made on behalf of third parties, see Vesna Danilovic, When the Stakes Are High: Deterrence and Conflict Among Major Powers (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2002). This is where efforts at deterring a Chinese invasion of Taiwan should begin.

Giving Taiwan more bite

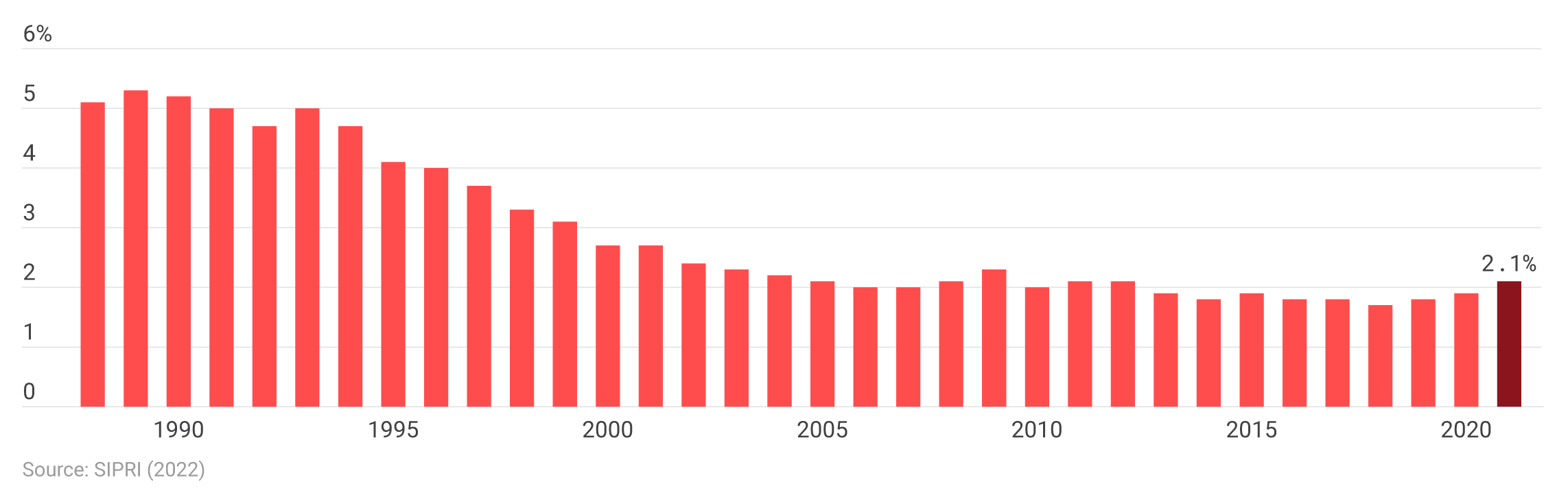

Chinese military strategists assume that the Taiwanese would resist an invasion of their island.12Analysts agree that the Taiwanese military faces readiness problems, but there is evidence that the Taiwanese public would be willing to fight against a Chinese invasion force. See, for example, Lin Chia-nan, “Poll says 72.5% of Taiwanese Willing to Fight Against Forced Unification by China,” Taipei Times, December 30, 2021, https://www.taipeitimes.com/News/front/archives/2021/12/30/2003770419. Taiwan’s problem is not credibility but capability. Taiwan currently lacks the firepower necessary to deter China on its own given its paltry investments in its own defense, particularly A2/AD systems that fortify its coastlines.13Eugene Gholz, Benjamin Friedman, and Enea Gjoza, “Defensive Defense: A Better Way to Protect U.S. Allies in Asia,” Washington Quarterly 42, no. 4 (2019): 171–189. For example, Taipei spends only around 2.1 percent of its GDP on defense, amounting to roughly 16 billion U.S. dollars annually. By contrast, in the late 1980s, Taiwan spent more than 5 percent of a much smaller GDP on defense. Years of underinvestment have left Taiwan’s military poorly organized to withstand a major assault by the People’s Liberation Army (PLA).14As Paul Huang concludes, “Taiwan’s military, as well as its economy, critical infrastructure, mobilization capacity, and society as a whole, is simply not built for fighting a protracted war totally cut off from the air and the sea.” See Paul Huang, “Threats to Taiwan’s Security from China’s Military Modernization,” in Meeting China’s Military Challenge: Collective Responses of U.S. Allies and Security Partners (NBR Special Report no. 96), ed. Bates Gill (Washington, DC: National Bureau of Asian Research, 2022), 25–35, at https://www.nbr.org/publication/meeting-chinas-military-challenge-collective-responses-of-u-s-allies-and-partners/. Every branch of Taiwan’s military is undermanned and under-resourced, while analysts have judged the island’s reserve forces to be virtually unusable.15Paul Huang, “Taiwan’s Military Is a Hollow Shell,” Foreign Policy, February 15, 2020, https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/02/15/china-threat-invasion-conscription-taiwans-military-is-a-hollow-shell.

Taiwanese defense spending as a percentage of GDP

Taiwan’s defense spending has fallen as a share of its GDP since the late 1980s. It has the capacity to increase spending to enhance its ability to deter China.

For it to deter China, it is imperative Taiwan spend more on defense—and invest in the “right kind” of defensive weaponry.16Jared M. McKinney and Peter Harris, “Broken Nest: Deterring China from Invading Taiwan,” Parameters 51, no. 4 (2021): 23–36. Eugene Gholz, Benjamin Friedman, and Enea Gjoza cast this argument in terms of “defensive defense.”17Gholz, Friedman, and Gjoza, “Defensive Defense.” As they explain, it makes little sense for the United States (or any other power) to threaten offensive reprisals against China given that the PLA has developed sophisticated defenses against such attacks. The technological reality of modern warfare means it would be more effective, less costly, and less risky for Taiwan to invest in the weapons, training, and tactics needed to mount an effective defense of its own. If leveraged correctly, Taiwan’s geography and the technological trajectory of military power can be used to raise the cost of a possible Chinese invasion such that rational Chinese leaders might be deterred from attempting such an assault in the first place. But this means investment in resilient anti-access/ area denial (A2/AD) capabilities, not expensive offensive weaponry that could be more easily destroyed in a PLA first-wave attack.18See also James Timbie and James O. Ellis Jr., “A Large Number of Small Things: A Porcupine Strategy for Taiwan,” Texas National Security Review 5, no. 1 (2021/2022): 83–93; and William S. Murray, “Revisiting Taiwan’s Defense Strategy,” Naval War College Review 61, no. 3 (2008): 13–31.

If it invests more in the right A2/AD capabilities, Taiwan might be able to stave off a Chinese invasion for some time. However, Taiwan’s strategy for deterring China should also include the threat of waging an insurgency should PLA forces manage to establish bridgeheads on the island and begin to seize population centers. This means investment in the Taiwanese army (most analysts recognize that Taiwan’s navy and air force are likely to be destroyed quickly as a result of a Chinese invasion, whereas its army might well prove to be more resilient) but it will also require preparing civilians for a well-resourced resistance campaign.19McKinney and Harris, “Broken Nest,” 29–30.

Finally, leaders in Taipei should make every effort to convince Beijing that an invasion of Taiwan would result in political ostracization. As Russia’s experience in Ukraine shows, large-scale invasions are not just difficult to pull off on the battlefield—they are also hard to defend in the court of international opinion. Russia today is more isolated than ever before. This is not a fate Chinese leaders should want for themselves. As well as threatening stiff military resistance and a bloody insurgency, it would serve the Taiwanese government well to emphasize the dire political costs that China would pay for the crime of aggression.

There is no way to tell in advance whether Taiwan could win a defensive war against China. As with any war, the outcome would depend on the number and type of forces committed by either side, the strategies and tactics used, wartime leadership, and sheer luck, among other factors. This means that Taipei cannot credibly threaten to stop a Chinese invasion in its tracks. What Taiwan can threaten, however, is that China will pay an intolerably high cost as the price of invasion. Such a threat can be made severe and credible enough to form the backbone of any strategy of deterrence across the Taiwan Strait.

Regional and global responses

As noted above, the Taiwanese obviously have the most to lose from a Chinese invasion of their island. Next in line, however, are East Asian states such as Japan, South Korea, the Philippines, and Australia. While it would be wrong to overstate the importance to regional powers of Taiwan remaining de facto independent from China (Taiwan’s security is not an existential issue for any of its neighbors),20On the limited military value of Taiwan to China, see Mike Sweeney, “How Militarily Useful Would Taiwan Be to China?,” Defense Priorities, April 12, 2022, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/how-militarily-useful-would-taiwan-be-to-china. an invasion of Taiwan would nevertheless give regional states ample reason to rethink their national security strategies. It should be the policy of the United States to encourage regional actors to make credible threats against Beijing—military, economic, and diplomatic—that will be carried out in the event of an attack on Taiwan, even if these measures fall short of military intervention on Taiwan’s behalf.21McKinney and Harris, “Broken Nest,” 31–32.

States such as Japan22Ryan Ashley, “Japan’s Revolution on Taiwan Affairs,” War on the Rocks, November 23, 2021, https://warontherocks.com/2021/11/japans-revolution-on-taiwan-affairs. and Australia23“‘Inconceivable’ Australia Would Not Join U.S. to Defend Taiwan—Australian Defence Minister,” Reuters, November 12, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/inconceivable-australia-would-not-join-us-defend-taiwan-australian-defence-2021-11-12. already made declarations that an attack on Taiwan would be treated as a grave national security concern and perhaps even a matter for collective defense. Worryingly, however, Japanese and Australian statements of sympathy for Taiwan have been couched alongside an implicit assumption the United States will lead a multilateral intervention to defend the island. This is the wrong approach. Given that America’s interest in defending Taiwan is uncertain, it diminishes the credibility of regional powers’ threats against Beijing if these threats are made contingent on U.S. willingness to join the fray.

Instead, regional actors should be encouraged to make clear how their own national interests would be affected by a Chinese attack on Taiwan. If China’s neighbors perceive Taiwan’s fate to be connected with their own national security, then this should be made clear to Beijing. Ideally, China must be left in no doubt that Japan, Australia, South Korea, the Philippines, and others would be forced to rethink their national security strategies in the shadow of an enlarged and aggressive Chinese state.24This could take the form of legislation similar to America’s Taiwan Relations Act, which defines “any effort to determine the future of Taiwan by other than peaceful means, including by boycotts or embargoes, [as] a threat to the peace and security of the Western Pacific area and of grave concern to the United States.” It would serve as a form of hands-tying for regional powers to adopt similar legislation, raising the likelihood of a forceful response from the government of the day. Of course, there are limits to what China can be made to fear. Regional powers cannot credibly threaten military reprisals against a nuclear-armed China. However, it is nevertheless important for America’s friends and allies in East Asia to emphasize their willingness to respond forcefully to a Chinese invasion of Taiwan with even more balancing. This is for the simple reason that they are affected by the balance of power in their own region—a logic that China will understand.

Recent events in Europe are instructive. In the run-up to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, President Biden made it clear that no U.S. troops would be committed to the warzone. This was the right approach. Yet even though President Biden refused to commit U.S. forces to Ukraine, this did not stop America’s allies and partners from inflicting punishing economic sanctions on Moscow, announcing large hikes in defense spending, isolating Russia diplomatically, and sending substantial amounts of lethal military aid to assist in the Ukrainian war effort. European states took these measures against Russia because it was clearly in their self-interest to establish the precedent that Russian aggression would not go unchecked.

While the United States lent great assistance to the Western effort to punish Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, it is likely that European governments would have moved against Russia even without U.S. help. China must be made to believe that same logic applies regarding Taiwan and East Asia: that an invasion of Taiwan would provoke regional powers to balance against China out of self-interest, not because of anything decided in Washington. The sight of the United States and its allies—European states, of course, but also Japan, South Korea, and Australia—adopting a unified response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine has given Beijing a reason to believe an invasion of Taiwan might meet with a similarly stiff multilateral response. To preserve stability in East Asia, however, it is important regional powers convince Chinese leaders that a severe regional response is assured and not just possible.

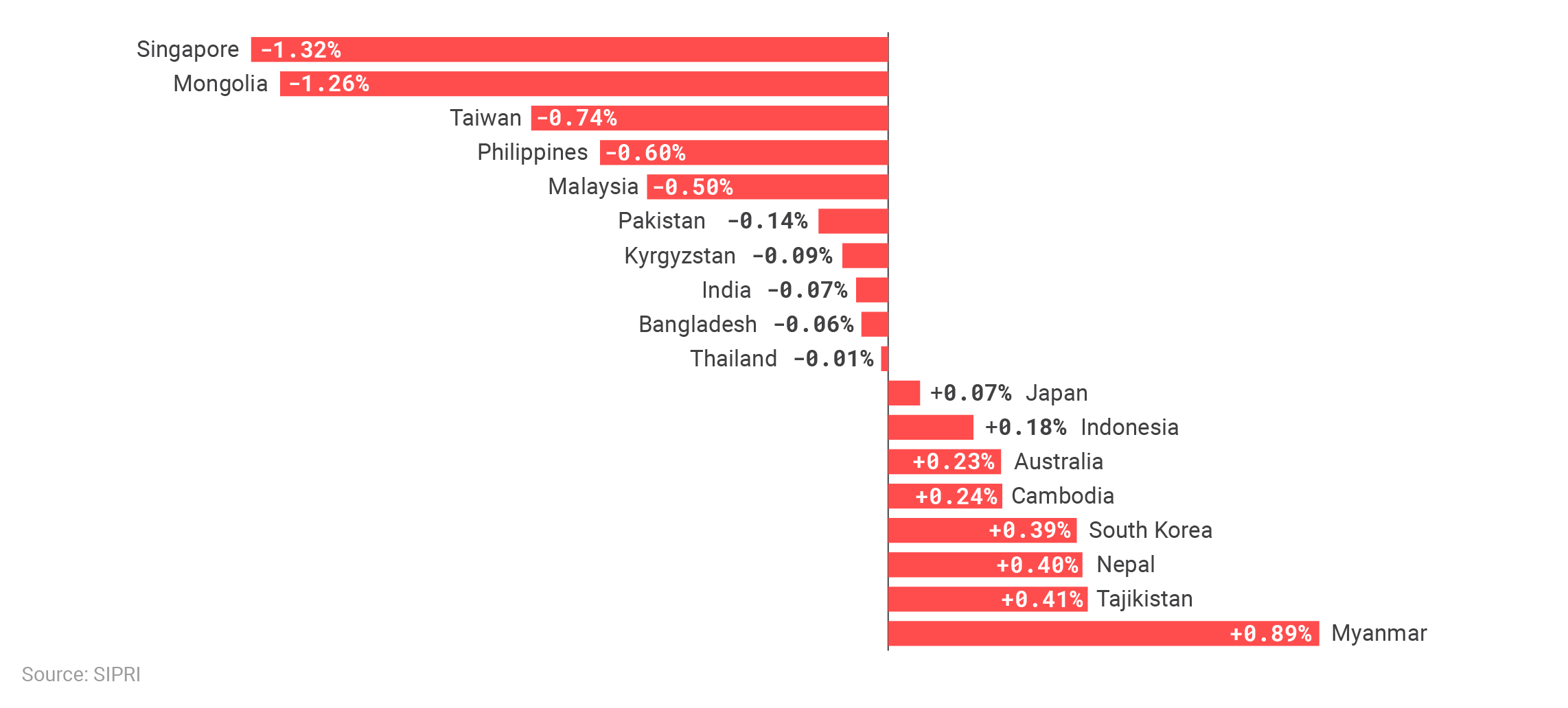

Change in military spending as a percentage of GDP (2000–2020)

As a share of each country’s GDP, annual defense spending has decreased for several Asian countries in the last two decades, including Taiwan and India.

To make their threats more credible—and thus more effective at deterring China—regional powers must be transparent about how they plan to respond to an invasion of Taiwan.25In other words, they should engage in a strategy of “general deterrence” (as opposed to “immediate deterrence”). On the difference between general and immediate deterrence, see Stephen Quackenbush, Understanding General Deterrence: Theory and Application (Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), 4–5. They should announce specific, credible measures they commit to carrying out—e.g., increased defense spending, plans to procure specific weapons, and a threat to develop regional defensive pacts that do not center on the United States. By making these plans known in advance, perhaps via the publication of policy documents or even binding legislation, leaders will go some way toward tying their hands in the event of a war over Taiwan. There is no guarantee that the prospect of a worsened security environment will deter China from invading Taiwan, but it is one thing that regional powers can credibly threaten against Beijing given their clear self-interest in preserving peace in Asia.26Before his invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, it is doubtful that President Putin anticipated that Germany and Poland would hike defense spending to 2 and 3 percent of GDP, respectively; that neutral Sweden would send arms to Ukraine and non-aligned Switzerland would join economic sanctions; and that Finland would petition for NATO membership. However, the act of invading Ukraine seems to have impressed on European states that they have a self-interest in beating back Russian aggression. Had Putin been certain that this would happen in response to an attack on Ukraine, he would have been at least somewhat more likely to decide against invading in the first place. The task for East Asian states is to convince China that an attack on Taiwan would invite a similar response: not a great-power war, but regional states investing in substantial military buildups out of self-interest.

Economic and political pressure

Threats of a worsened regional security environment should be joined with economic threats to punish China for an armed attack on Taiwan. Again, the Russian invasion of Ukraine provides some useful lessons. Just days after the Russian attack, Western leaders orchestrated an impressive range of economic punishments against Russia—far more extensive, perhaps, than even they had planned prior to the invasion. Governments that had previously sought to downplay expectations about economic sanctions were pushed by domestic and international opinion to implement punishments that seemed unlikely just weeks earlier—Germany’s cancellation of the Nord Stream 2 pipeline, for example.

Given its deep integration into the world economy and preexisting concerns of Western “decoupling,” China can be made to fear a similar response to that experienced by Russia.27It might be countered that China cannot be deterred by threats of economic punishment. But there is much literature in international relations on the economic causes of peace. See, for example, Patrick J. McDonald, The Invisible Hand of Peace: Capitalism, the War Machine, and International Relations Theory (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009). What is more, there is evidence that Xi has been deterred from invading Taiwan in the recent past because of a concern that the Chinese economy would be cut off from indispensable high-tech imports—especially the supply of semiconductors. David E. Sanger, Catie Edmondson, and Thomas Kaplan, “Senate Poised to Pass Huge Industrial Policy Bill to Counter China,” New York Times, June 7, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/07/us/politics/senate-china-semiconductors.html. Indeed, the economic sphere is one where the United States—and some of its allies outside of East Asia, such as those in Europe—can make credible threats against China. Washington could use the logics of hands-tying and sunk costs (described above) to assure Beijing of swift economic punishment to follow any invasion of Taiwan. This might take the form of prospective legislation, for example.

Beijing will always have some doubts about whether the United States would truly follow through on costly economic warfare against China. But at the very least, the Western response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has given leaders in Beijing cause to wonder whether similar economic punishments would be triggered by an invasion of Taiwan.28In March 2022, CIA Director William Burns told Congress that Chinese leaders were “unsettled” by the unity displayed by Europe and the United States in the immediate aftermath of the Russian attack. See “Hearing on Annual Worldwide Threats,” U.S. House of Representatives, Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence, March 8, 2022, https://docs.house.gov/meetings/IG/IG00/20220308/114469/HHRG-117-IG00-Transcript-20220308.pdf. Again, however, it is essential that such multilateral economic punishments are made clear in advance so that they can work as a form of “general deterrence” rather than being invoked as a panicked attempt at “immediate deterrence.”29Quackenbush, Understanding General Deterrence, 4–5. One possible weakness of the sanctions leveled against Russia is that the full extent of the economic sanctions was uncertain prior to the invasion. Deterrence would have been stronger (even if not ironclad) had Russian President Putin been convinced that Western governments would follow through on their most severe threats, such as removing Russia’s banks from SWIFT and sanctioning its central bank.30The point is not that leaders such as Putin or Xi Jinping always value economic stability more than national security concerns. On the contrary, there are almost certainly scenarios in which Chinese leaders would pay significant economic costs in order to capture Taiwan. Rather, the credible threat of severe economic punishments should be considered one tool of several with which a deterrer can try to alter the cost-benefit analysis of an adversary. See fn. 27.

For the threat of economic punishment to be effective at deterring an invasion of Taiwan, the United States (and its allies and partners) must refrain from applying punitive economic pressure to China today. The imposition of sanctions must only happen in the event of a Chinese armed attack, not before. Levying economic costs on China absent an invasion of Taiwan could signal to Beijing that it has nothing more to lose in economic terms.

Sanctions must also be tied to specific policy demands. Another problem with the sanctions on Russia is that they were imposed without any clear suggestion of how or when they would be rolled back, which gave Putin few incentives to stop his invasion once it had begun. Beijing must be left in no doubt about the economic punishments that would follow an unprovoked attack on Taiwan (by contrast, keeping China guessing about U.S. and allied military responses remains a sound policy), but China must also be assured that the purpose of any sanctions would be to compel a restoration of the status quo—not to secure regime change in Beijing or preclude the future possibility of peaceful reunification between China and Taiwan.

Finally, the United States, Taiwan, and their regional partners should threaten Beijing with diplomatic isolation, a loss of prestige, and pariah status. This is another area where the United States and its allies can play on preexisting Chinese fears of ostracization. Anti-China sentiment is already strong in countries like the United States and Australia. Even if they wanted to, politicians in the West might not be able to prevent such sentiment tipping over into outright hostility towards Beijing.31The Taiwan Relations Act explicitly links U.S. diplomatic relations with Beijing to “the expectation that the future of Taiwan will be determined by peaceful means.” Although this does not constitute a legally binding commitment to revoke diplomatic recognition of the People’s Republic of China in the event of an invasion, it does strengthen the credibility of any U.S. threats to inflict diplomatic sanctions against China over the Taiwan issue. After the invasion of Ukraine, Putin became persona non grata on the world stage. In the event of an attack on Taiwan, the diplomatic backlash against China might well be much greater. The United States can help to convince Beijing of this likelihood—but regional capitals such as Canberra, Seoul, Tokyo, and Manilla must also play their part.

The status quo benefits all parties

To be clear, none of the threats described above—even if China knew with certainty that they would be carried out—are likely to be sufficient to deter China from invading Taiwan on their own. But if properly assembled into a package of credible deterrents, it becomes possible to envisage a scenario where the expected costs to China of invading Taiwan could outweigh the expected benefits. Huge military losses inflicted by Taiwanese defenders, the prospect of facing a long and drawn-out insurgency, a severely worsened security environment, heavy economic sanctions, and diplomatic isolation—these are all grave threats that would place a strain on Chinese domestic politics and upend several of Beijing’s long-term international ambitions. Meanwhile, actors with a strong interest in preserving peace and stability in East Asia should see few downsides in attempting what has been proposed. Taiwan, in particular, can only benefit from the development of autonomous deterrents.

Even so, it would be wrong to rely on deterrence alone to preserve the peace across the Taiwan Strait. Ensuring that Beijing expects to pay high costs for invading Taiwan is only one-half of the equation; it is also necessary to increase the benefits to Beijing of choosing to adhere to the status quo. As an external power, there are limits to what the United States can do in this regard. Taiwanese leaders must assume the burden of assuring China that there is still a non-trivial chance of a peaceful settlement that will satisfy Beijing’s core interests. But the United States has sovereignty over its own foreign policy and should refrain from making statements and taking actions that are inconsistent with its longstanding One China policy.

America’s One China policy has several components. Most obviously, it means continuing to discourage a Taiwanese declaration of independence. However, it also means recognizing (without supporting) China’s position that the island of Taiwan is part of China; opposing Taiwanese membership in most international organizations; maintaining only unofficial relations with Taipei; and favoring a peaceful resolution of the dispute between Beijing and Taipei. These have been the primary pillars of U.S. Taiwan policy since the normalization of ties between the United States and PRC—a set of policies that, taken together, have helped to dissuade Beijing from overturning the status quo by force.

President Biden has unwisely tugged U.S. policy in the opposite direction of upholding the One China policy. On several occasions, for example, he has suggested that the United States regards Taiwan as a treaty ally and would intervene militarily to defend the island.32John Ruwitch, “Would the U.S. Defend Taiwan if China Invades? Biden Said Yes. But It’s Complicated,” NPR, October 28, 2021, https://www.npr.org/2021/10/28/1048513474/biden-us-taiwan-china. Ely Ratner, the assistant secretary of defense for Indo-Pacific security affairs, made separate comments to the effect of Taiwan being of strategic value to the United States insofar as it remains politically distinct from China—contradicting longstanding policy that the United States does not take a position on whether Taiwan should be united with the Mainland.33Michael D. Swaine, “US Official Signals Stunning Shift in the Way We Interpret ‘One China’ Policy,” Responsible Statecraft, December 10, 2021, https://responsiblestatecraft.org/2021/12/10/us-official-signals-stunning-shift-in-the-way-we-interpret-one-china-policy. Meanwhile, former Secretary of State Mike Pompeo has even argued the United States should recognize Taiwan as a sovereign state.34Ben Blanchard, “U.S. Should Recognise Taiwan, Former Top Diplomat Pompeo Says,” Reuters, March 4, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/us-should-recognise-taiwan-former-top-diplomat-pompeo-says-2022-03-04. These statements do more than just chip away at the One China policy; they are completely at odds with it. It is not difficult to imagine that such proposals could lead Beijing to conclude that U.S. policy is shifting in favor of Taiwanese independence instead of remaining uncommitted on the question of Taiwan’s political status.

Given these recent developments, it is important that the Biden administration take steps to assure China that American foreign policy remains consistent with previous interpretations of the One China policy. As much as possible, the United States should enjoin its regional allies to make similar statements—and to back them up with real policies that strengthen the appeal of the status quo from China’s perspective. The point here is that Beijing will only forgo a “military solution” if it thinks there is a meaningful chance of peaceful reunification with Taiwan.35McKinney and Harris, “Broken Nest,” 33. As Jared McKinney has said, “A question delayed is an invasion denied.”36Quoted in Liam Gibson, “Taiwan’s ‘Silicon Shield’: Why Island May Not Be the Next Ukraine,” Al Jazeera, April 1, 2022, https://www.aljazeera.com/economy/2022/4/1/silicon-shield-why-taiwan-is-not-the-next-ukraine.

There are historical precedents for U.S. administrations undertaking “course corrections” of this sort. In 1996, for example, President Bill Clinton sent two aircraft carrier battle groups to the Taiwan Strait as a means of compelling China to cease threatening behavior against Taiwan. Clinton’s move raised questions about his commitment to the One China policy of his predecessors. Yet in 1998, the Clinton administration issued the so-called “Three No’s” on Taiwan (no independence for Taiwan, no deviation from the “One China” principle, and no Taiwanese membership in state-based international organizations) as a means of calming Beijing’s fears about Taiwanese independence.37Jim Mann, “Clinton 1st to OK China, Taiwan ‘3 No’s’,” Los Angeles Times, July 8, 1998, https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1998-jul-08-mn-1834-story.html. This was a sensible move to reduce tensions across the Strait and reassure Beijing that U.S. policy still envisaged peaceful unification as a possible outcome.

In the final analysis, the Biden Administration should be reminded that U.S. national interests are best served by upholding the status quo. Overturning America’s One China policy, whether in whole or in part, would undermine stability in East Asia, unnecessarily provoke China, and put U.S. interests in jeopardy. It is important to reassure both Beijing and Taipei—and leaders in Washington, for that matter—that the status quo is sustainable, the United States is not trying to erode core tenets of the U.S.-China relationship, and that U.S. policy remains based on the longstanding formulation of its One China policy.

Why “strategic clarity” won’t work

Instead of the measures described above, some analysts call for the United States to assume the burden of deterring a Chinese invasion of Taiwan by embracing “strategic clarity.”38Haass and Sacks, “American Support for Taiwan Must Be Unambiguous”; Haass and Sacks, “The Growing Danger of U.S. Ambiguity on Taiwan.” In effect, this would mean attempting to threaten China with the certainty of a U.S. military intervention on behalf of Taiwan. This is bad policy from the perspectives of the United States, Taiwan, and regional powers.

From the U.S. perspective, providing strategic clarity is unwise for several reasons. First, it would violate core principles of burden-sharing by removing any incentive for Taiwan to develop credible means of self-defense. Even worse, however, it would nominally commit the United States to fighting a devastating great-power war at a time of China’s choosing. As described above, America’s interest in defending Taiwan is not strong enough that anyone—least of all leaders in Beijing—can be expected to believe such a threat. Even if the United States announced a policy of defending Taiwan against China, such statements would be unlikely to succeed as a deterrent so long as China correctly judges that U.S. vital interests are not at stake when it comes to Taiwan. That is, there is a high chance that Beijing would dismiss strategic clarity as a bluff.

If the United States did fight a war over Taiwan, it is worth considering whether fighting such a war could result in the United States occupying a better strategic position than before. In fact, it is difficult to envisage a postwar scenario that would leave the United States in a better position than it occupies today. The United States would obviously be worse off if its forces lost a war over Taiwan, which is a real possibility (America would stand to suffer enormous losses even if a war over Taiwan remained conventional; the costs would be even higher, of course, if nuclear weapons were used). However, even a “successful” defense of Taiwan would likely leave U.S. forces in the unenviable position of garrisoning the island indefinitely as a deterrent against the next Chinese attack.39Andrew Scobell, “How China Manages Taiwan and Its Impact on PLA Missions,” in Beyond the Strait: PLA Missions Other Than Taiwan, eds. Roy Kamphausen, David Lai, and Andrew Scobell (Carlisle, PA: Strategic Studies Institute, 2008), 29–38. Even if war over Taiwan led to the collapse of the PRC regime—an unlikely outcome, but not impossible depending upon how the war played out—it would create serious economic and security problems for the United States and its regional allies.

From Taiwan’s perspective, strategic clarity is obviously seductive.40Raymond Kuo, “The Counter-Intuitive Sensibility of Taiwan’s New Defense Strategy,” War on the Rocks, December 6, 2021, https://warontherocks.com/2021/12/the-counter-intuitive-sensibility-of-taiwans-new-defense-strategy/. However, there are enormous risks in predicating the survival of Taiwan’s de facto political independence on the expectation that a sitting U.S. president will decide to intervene on Taiwan’s behalf and will not face any domestic or international impediments to doing so. As Joshua Rovner has argued, strategic ambiguity is a fact, not a policy.41Josh Rovner, “Ambiguity Is a Fact, Not a Policy,” War on The Rocks, July 22, 2021, https://warontherocks.com/2021/07/ambiguity-is-a-fact-not-a-policy.

It will always be uncertain that the United States will risk a conventional (let alone a nuclear) war over Taiwan. Whether leaders in Washington choose to intercede on Taiwan’s behalf will depend upon innumerable factors that strategic planners in Taiwan cannot hope to anticipate with any degree of certainty, even if U.S. policy stated it would defend the island. Instead of relying on the United States to rescue them, Taiwanese leaders should focus on developing autonomous means of deterrence.

Finally, strategic clarity from the United States would undermine regional balancing. As with Taiwan, the promise of strategic clarity would encourage regional states to rely on Washington as a security-provider. If the United States failed to follow through on commitments to Taiwan, however, regional states would find themselves badly exposed. They would simultaneously face strong incentives to respond to Chinese aggression while having tied themselves to a power unwilling to provide meaningful assistance.

It would be far better for regional powers if they could make their plans to deter China independently of the United States. It is possible to envisage such an “antifragile” balancing coalition taking shape, but only if China can be convinced that its aggressive actions will be met with self-interested (and thus self-enforcing) reactions from neighboring states.42A system is “antifragile” if it gets stronger in response to external stress rather than weaker. See Nassim Nicholas Taleb, Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder (New York, NY: Random House, 2012). Threats from the United States that are unmoored from reasonable definitions of the U.S. national interest are unlikely to have the same effect. Perhaps counterintuitively, Washington can best help regional states to deter China by gradually drawing down U.S. forces in East Asia, which might provide the stimulus for regional states to fashion their own (more credible) means of deterring and defending against Chinese aggression.43Gholz, Friedman, and Gjoza, “Defensive Defense.”

For these reasons, proposals for the United States to clarify its security commitments to Taiwan do not constitute a long-term strategy for deterring China. At best, relying on U.S. threats of war is a costly gamble to preserve a fragile peace. More realistically, China’s rise means that the threat of military reprisals has become infeasible as a standalone deterrent. Adopting a policy of strategic clarity might therefore amount to the United States tying its hands to fight a war at a time of China’s choosing—the epitome of bad policy.

Upholding the status quo in the Taiwan Strait

The United States favors a peaceful resolution of the dispute over Taiwan. Today, however, a negotiated settlement to the Taiwan question is nowhere in sight—and, indeed, seems to be becoming less likely over time. According to some experts, the vanishing prospect of peaceful reunification has led Chinese leaders to give serious thought to an armed takeover of Taiwan.44Oriana Skylar Mastro, “The Taiwan Temptation: Why Beijing Might Resort to Force,” Foreign Affairs 100, no. 4 (2021): 58–67. Such an outcome would be detrimental to U.S. interests in East Asia. Even those who caution against inflating the strategic importance of Taiwan to the United States agree the optimal U.S. policy goal is to deter China from seizing Taiwan by force.45See, for example, Charles L. Glaser, “A U.S.-China Grand Bargain? The Hard Choice between Military Competition and Accommodation,” International Security 39, no. 4 (2015): 49–90, at 72-78, cited in McKinney and Harris, “Broken Nest,” 24.

To help avert war across the Taiwan Strait, the aims of U.S. policy should be to:

- Preserve Taiwan’s de facto political independence from Beijing until such a time as the two sides can reach a permanent political settlement on their relationship, even if such a settlement seems unimaginable at present.

- Resist military force being used to upend the status quo. This means deterring an unprovoked Chinese invasion while simultaneously opposing a unilateral declaration of Taiwanese independence, which would almost certainly precipitate a Chinese attack.

- Convince all sides the status quo is not only sustainable, but also mutually beneficial, and that alternatives to the status quo are laden with unacceptable levels of risk to regional security and global economic prosperity.

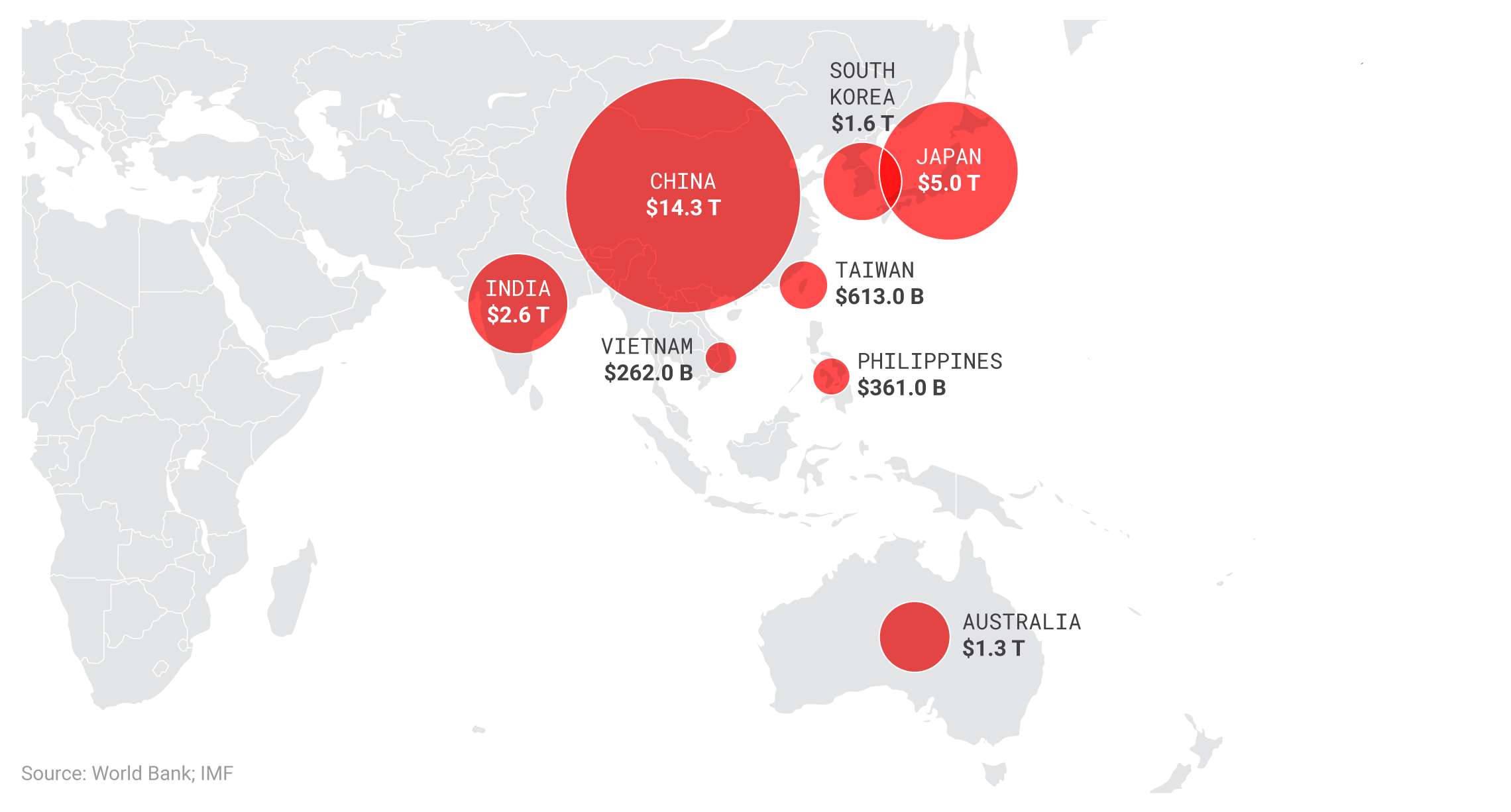

The best way to advance these goals is for the United States to facilitate those with most at stake—i.e., Taiwan and neighboring states in Asia—to develop their own means of collaborative deterrence. For Taiwan, this means investing in military capabilities that would inflict painful losses upon an invading Chinese force and Mainland installations. For regional actors like Japan, South Korea, the Philippines, and Australia, it means joining bold economic threats that would plunge the Chinese economy into dire straits with plans to massively ramp up military spending.

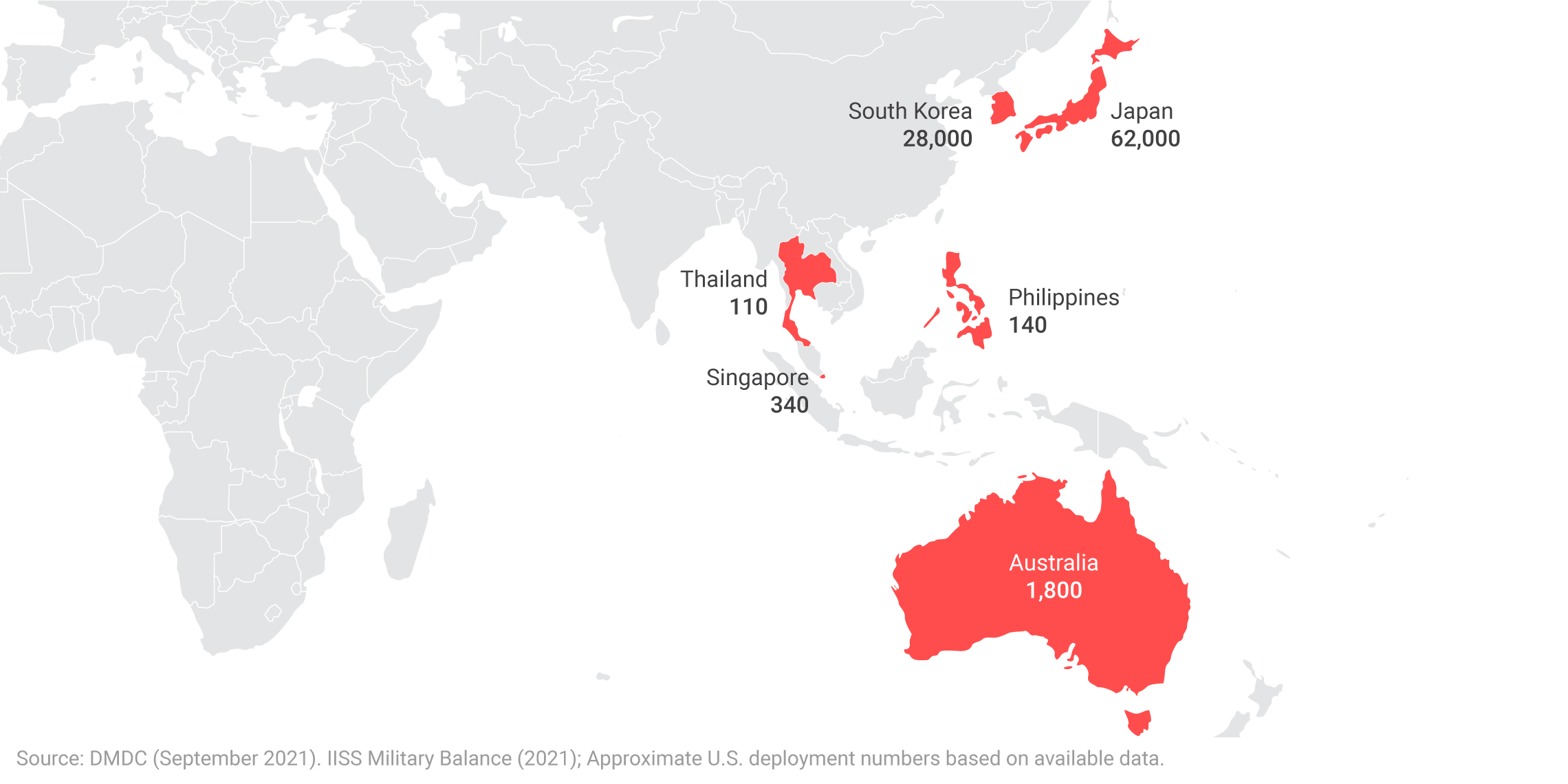

GDP of China relative to other regional powers and key neighbors

China is the preeminent economic power in East Asia, but its neighbors collectively possess the wealth to balance China by augmenting their military capabilities and cooperating. Their proximity to China also suggests they should do more to deter an invasion of Taiwan. By contrast, the United States is almost 8,000 miles away.

Instead of threatening to fight China over Taiwan, America’s role should be to “double-plate” others’ means of deterrence from afar while taking serious steps to reassure Beijing the status quo across the Taiwan Strait is sustainable, and that Washington is committed to upholding the basic principles that have defined U.S.-China relations for the past 40 years—namely, its One China policy and the commitments contained therein (opposition to Taiwanese independence, maintenance of only unofficial relations with Taiwan, and an acknowledgment of the Chinese position that Taiwan is a part of China). Using the threat of force to deny China its political ambitions could only ever work for as long as Beijing remained cowed. That era has passed. A new approach to deterrence is needed—one that relies more heavily on regional actors, carrots as well as sticks, and which learns from the lessons of recent history.

Endnotes

- 1As Mike Sweeney has put it, “Any battle over Taiwan will not just be a question of territorial aggression but a fight over the core conception of modern China’s soul.” See Mike Sweeney, “Why a Taiwan Conflict Could Go Nuclear,” Defense Priorities, March 4, 2021, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/why-a-taiwan-conflict-could-go-nuclear.

- 2Liping Xia, “China’s Nuclear Doctrine: Debates and Evolution,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, June 30, 2016, https://carnegieendowment.org/2016/06/30/china-s-nuclear-doctrine-debates-and-evolution-pub-63967.

- 3In March 2022, an opinion poll by the Taiwanese Public Opinion Foundation found that 55.9 percent of respondents doubted that the United States would intervene militarily on Taiwan’s behalf. See John Feng, “Taiwan Losing Faith in U.S. Rescue if China Invades—Poll,” Newsweek, March 23, 2022, https://www.newsweek.com/taiwan-public-opinion-poll-us-military-response-china-invasion-1690831.

- 4James M. Fearon, “Signaling Foreign Policy Interests: Tying Hands Versus Sinking Costs,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 41, no. 1 (1997): 68–90.

- 5Thomas C. Schelling, The Strategy of Conflict (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1960), 28–29, cited in Helen V. Milner and Peter B. Rosdendorff, “Domestic Politics and International Trade Negotiations: Elections and Divided Government as Constraints on Trade Liberalization,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 41, no. 1 (1997): 117–146. See also Thomas C. Schelling, Arms and Influence (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1966).

- 6Fearon, “Signaling Foreign Policy Interests.”

- 7Keith B. Payne, “The Taiwan Question: How to Think About Deterrence Now,” National Institute for Public Policy, November 15, 2021, https://nipp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/IS-509.pdf. See also Lyle Goldstein, “Raising the Minimum: Explaining China’s Nuclear Buildup,” Defense Priorities, April 5, 2022, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/raising-the-minimum-explaining-chinas-nuclear-buildup.

- 8Michèle Flournoy, “America’s Military Risks Losing Its Edge,” Foreign Affairs 100, no. 3 (2021): 76–90. See also Richard Haass and David Sacks, “American Support for Taiwan Must Be Unambiguous: To Keep the Peace, Make Clear to China That Force Won’t Stand,” Foreign Affairs, September 2, 2020, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/american-support-taiwan-must-be-unambiguous; and Richard Haass and David Sacks, “The Growing Danger of U.S. Ambiguity on Taiwan: Biden Must Make America’s Commitment Clear to China—and the World,” Foreign Affairs, December 13, 2021, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/china/2021-12-13/growing-danger-us-ambiguity-taiwan.

- 9Daryl Press calls this the “Current Calculus theory” of credibility. See Daryl G. Press, Calculating Credibility: How Leaders Assess Military Threats (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2005), 8–9.

- 10Michael J. Mazarr, Understanding Deterrence (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2018), 3.

- 11On the greater (“inherent”) credibility of threats made in self-defense as opposed to those made on behalf of third parties, see Vesna Danilovic, When the Stakes Are High: Deterrence and Conflict Among Major Powers (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2002).

- 12Analysts agree that the Taiwanese military faces readiness problems, but there is evidence that the Taiwanese public would be willing to fight against a Chinese invasion force. See, for example, Lin Chia-nan, “Poll says 72.5% of Taiwanese Willing to Fight Against Forced Unification by China,” Taipei Times, December 30, 2021, https://www.taipeitimes.com/News/front/archives/2021/12/30/2003770419.

- 13Eugene Gholz, Benjamin Friedman, and Enea Gjoza, “Defensive Defense: A Better Way to Protect U.S. Allies in Asia,” Washington Quarterly 42, no. 4 (2019): 171–189.

- 14As Paul Huang concludes, “Taiwan’s military, as well as its economy, critical infrastructure, mobilization capacity, and society as a whole, is simply not built for fighting a protracted war totally cut off from the air and the sea.” See Paul Huang, “Threats to Taiwan’s Security from China’s Military Modernization,” in Meeting China’s Military Challenge: Collective Responses of U.S. Allies and Security Partners (NBR Special Report no. 96), ed. Bates Gill (Washington, DC: National Bureau of Asian Research, 2022), 25–35, at https://www.nbr.org/publication/meeting-chinas-military-challenge-collective-responses-of-u-s-allies-and-partners/.

- 15Paul Huang, “Taiwan’s Military Is a Hollow Shell,” Foreign Policy, February 15, 2020, https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/02/15/china-threat-invasion-conscription-taiwans-military-is-a-hollow-shell.

- 16Jared M. McKinney and Peter Harris, “Broken Nest: Deterring China from Invading Taiwan,” Parameters 51, no. 4 (2021): 23–36.

- 17Gholz, Friedman, and Gjoza, “Defensive Defense.”

- 18See also James Timbie and James O. Ellis Jr., “A Large Number of Small Things: A Porcupine Strategy for Taiwan,” Texas National Security Review 5, no. 1 (2021/2022): 83–93; and William S. Murray, “Revisiting Taiwan’s Defense Strategy,” Naval War College Review 61, no. 3 (2008): 13–31.

- 19McKinney and Harris, “Broken Nest,” 29–30.

- 20On the limited military value of Taiwan to China, see Mike Sweeney, “How Militarily Useful Would Taiwan Be to China?,” Defense Priorities, April 12, 2022, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/how-militarily-useful-would-taiwan-be-to-china.

- 21McKinney and Harris, “Broken Nest,” 31–32.

- 22Ryan Ashley, “Japan’s Revolution on Taiwan Affairs,” War on the Rocks, November 23, 2021, https://warontherocks.com/2021/11/japans-revolution-on-taiwan-affairs.

- 23“‘Inconceivable’ Australia Would Not Join U.S. to Defend Taiwan—Australian Defence Minister,” Reuters, November 12, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/inconceivable-australia-would-not-join-us-defend-taiwan-australian-defence-2021-11-12.

- 24This could take the form of legislation similar to America’s Taiwan Relations Act, which defines “any effort to determine the future of Taiwan by other than peaceful means, including by boycotts or embargoes, [as] a threat to the peace and security of the Western Pacific area and of grave concern to the United States.” It would serve as a form of hands-tying for regional powers to adopt similar legislation, raising the likelihood of a forceful response from the government of the day.

- 25In other words, they should engage in a strategy of “general deterrence” (as opposed to “immediate deterrence”). On the difference between general and immediate deterrence, see Stephen Quackenbush, Understanding General Deterrence: Theory and Application (Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), 4–5.

- 26Before his invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, it is doubtful that President Putin anticipated that Germany and Poland would hike defense spending to 2 and 3 percent of GDP, respectively; that neutral Sweden would send arms to Ukraine and non-aligned Switzerland would join economic sanctions; and that Finland would petition for NATO membership. However, the act of invading Ukraine seems to have impressed on European states that they have a self-interest in beating back Russian aggression. Had Putin been certain that this would happen in response to an attack on Ukraine, he would have been at least somewhat more likely to decide against invading in the first place. The task for East Asian states is to convince China that an attack on Taiwan would invite a similar response: not a great-power war, but regional states investing in substantial military buildups out of self-interest.

- 27It might be countered that China cannot be deterred by threats of economic punishment. But there is much literature in international relations on the economic causes of peace. See, for example, Patrick J. McDonald, The Invisible Hand of Peace: Capitalism, the War Machine, and International Relations Theory (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009). What is more, there is evidence that Xi has been deterred from invading Taiwan in the recent past because of a concern that the Chinese economy would be cut off from indispensable high-tech imports—especially the supply of semiconductors. David E. Sanger, Catie Edmondson, and Thomas Kaplan, “Senate Poised to Pass Huge Industrial Policy Bill to Counter China,” New York Times, June 7, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/07/us/politics/senate-china-semiconductors.html.

- 28In March 2022, CIA Director William Burns told Congress that Chinese leaders were “unsettled” by the unity displayed by Europe and the United States in the immediate aftermath of the Russian attack. See “Hearing on Annual Worldwide Threats,” U.S. House of Representatives, Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence, March 8, 2022, https://docs.house.gov/meetings/IG/IG00/20220308/114469/HHRG-117-IG00-Transcript-20220308.pdf.

- 29Quackenbush, Understanding General Deterrence, 4–5.

- 30The point is not that leaders such as Putin or Xi Jinping always value economic stability more than national security concerns. On the contrary, there are almost certainly scenarios in which Chinese leaders would pay significant economic costs in order to capture Taiwan. Rather, the credible threat of severe economic punishments should be considered one tool of several with which a deterrer can try to alter the cost-benefit analysis of an adversary. See fn. 27.

- 31The Taiwan Relations Act explicitly links U.S. diplomatic relations with Beijing to “the expectation that the future of Taiwan will be determined by peaceful means.” Although this does not constitute a legally binding commitment to revoke diplomatic recognition of the People’s Republic of China in the event of an invasion, it does strengthen the credibility of any U.S. threats to inflict diplomatic sanctions against China over the Taiwan issue.

- 32John Ruwitch, “Would the U.S. Defend Taiwan if China Invades? Biden Said Yes. But It’s Complicated,” NPR, October 28, 2021, https://www.npr.org/2021/10/28/1048513474/biden-us-taiwan-china.

- 33Michael D. Swaine, “US Official Signals Stunning Shift in the Way We Interpret ‘One China’ Policy,” Responsible Statecraft, December 10, 2021, https://responsiblestatecraft.org/2021/12/10/us-official-signals-stunning-shift-in-the-way-we-interpret-one-china-policy.

- 34Ben Blanchard, “U.S. Should Recognise Taiwan, Former Top Diplomat Pompeo Says,” Reuters, March 4, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/us-should-recognise-taiwan-former-top-diplomat-pompeo-says-2022-03-04.

- 35McKinney and Harris, “Broken Nest,” 33.

- 36Quoted in Liam Gibson, “Taiwan’s ‘Silicon Shield’: Why Island May Not Be the Next Ukraine,” Al Jazeera, April 1, 2022, https://www.aljazeera.com/economy/2022/4/1/silicon-shield-why-taiwan-is-not-the-next-ukraine.

- 37Jim Mann, “Clinton 1st to OK China, Taiwan ‘3 No’s’,” Los Angeles Times, July 8, 1998, https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1998-jul-08-mn-1834-story.html.

- 38Haass and Sacks, “American Support for Taiwan Must Be Unambiguous”; Haass and Sacks, “The Growing Danger of U.S. Ambiguity on Taiwan.”

- 39Andrew Scobell, “How China Manages Taiwan and Its Impact on PLA Missions,” in Beyond the Strait: PLA Missions Other Than Taiwan, eds. Roy Kamphausen, David Lai, and Andrew Scobell (Carlisle, PA: Strategic Studies Institute, 2008), 29–38.

- 40Raymond Kuo, “The Counter-Intuitive Sensibility of Taiwan’s New Defense Strategy,” War on the Rocks, December 6, 2021, https://warontherocks.com/2021/12/the-counter-intuitive-sensibility-of-taiwans-new-defense-strategy/.

- 41Josh Rovner, “Ambiguity Is a Fact, Not a Policy,” War on The Rocks, July 22, 2021, https://warontherocks.com/2021/07/ambiguity-is-a-fact-not-a-policy.

- 42A system is “antifragile” if it gets stronger in response to external stress rather than weaker. See Nassim Nicholas Taleb, Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder (New York, NY: Random House, 2012).

- 43Gholz, Friedman, and Gjoza, “Defensive Defense.”

- 44Oriana Skylar Mastro, “The Taiwan Temptation: Why Beijing Might Resort to Force,” Foreign Affairs 100, no. 4 (2021): 58–67.

- 45See, for example, Charles L. Glaser, “A U.S.-China Grand Bargain? The Hard Choice between Military Competition and Accommodation,” International Security 39, no. 4 (2015): 49–90, at 72-78, cited in McKinney and Harris, “Broken Nest,” 24.

More on Asia

Featuring Jennifer Kavanagh

October 4, 2025

Featuring Jennifer Kavanagh

September 29, 2025