November 19, 2021

“Maximum pressure” harms diplomacy and increases risks of war with Iran

Key points

- With an economy less than a third the size of the U.S. defense budget and a military ill-suited for offensive operations, Iran is at best a minor threat to the U.S., and one in a region of limited strategic importance. The U.S. need not obsess over Iran policy.

- While Iran does not threaten vital U.S. interests, U.S. policy does seek to moderate Iran’s behavior and restrict its nuclear weapons development. That is why the U.S. negotiated the JCPOA, an agreement with Iran, Europe’s major powers, Russia, and China to constrain Iran’s nuclear activities.

- The Trump administration abrogated the JCPOA and imposed a policy of “maximum pressure” designed to compel Iran to renegotiate on nuclear issues and moderate its foreign policy. Rather than capitulate to U.S. demands, Iran expanded its nuclear program and increased its aggression in the Middle East.

- U.S. withdrawal from the JCPOA and imposition of a maximum pressure strategy harmed diplomatic efforts with Iran and increased the prospects of direct conflict.

- The Biden administration has so far continued the policy it inherited from the Trump administration. With nuclear negotiations between the U.S. and Iran predictably stalled, U.S. officials should abandon maximum pressure.

- Ongoing diplomacy is the best path to revive the JCPOA, and more importantly, lower the risks of war. Even if the JCPOA dissolves completely, U.S.-Iran diplomacy, including on nuclear issues, should continue. War with Iran is not worth the costs.

Assessing the current state of nuclear talks

On May 8, 2018, President Donald Trump announced the United States would withdraw from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA, or Iran nuclear deal). In its place, President Trump reimposed economic sanctions the United States previously committed to lift as part the agreement, and his administration pursued a “maximum pressure” campaign with two goals: (1) to force Iran to renegotiate an agreement on its nuclear program to remove its path to a bomb and (2) to pacify Iran’s foreign policy.1“President Donald J. Trump Is Ending United States Participation in an Unacceptable Iran Deal,” White House, May 8, 2018, https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/briefings-statements/president-donald-j-trump-ending-united-states-participation-unacceptable-iran-deal/. That policy failed, yet it continues today. Tehran responded to approximately one year of U.S. pressure by escalating its malign behavior in the region and ceasing its obligations to restrict nuclear activities established under the JCPOA. Upon entering office, President Joe Biden committed to negotiating a mutual return of both parties to the deal. Returning to the JCPOA would be a first step to what Secretary of State Antony Blinken called “a longer and stronger agreement.”2“Secretary Antony J. Blinken at a Press Availability,” U.S. Department of State, March 24, 2021, https://www.state.gov/secretary-antony-j-blinken-at-a-press-availability-3.

After months of communication between U.S. and Iranian officials, indirect talks began in April 2021.3Ellen Knickmeyer and Raf Casert, “‘First Step:’ U.S., Iran to Begin Indirect Nuclear-Limit Talks,” Associated Press, April 2, 2021, https://apnews.com/article/us-iran-indirect-talks-nuclear-program-a6558ac21b600cb7a3c8542f18a7aece. In Vienna, the United States and Iran (with assistance from Germany, France, the United Kingdom, the European Union, Russia, and China) exchanged proposals and stated their expectations for how the negotiations should proceed. The parties established working groups to determine which sanctions the United States must remove and which nuclear concessions Iran must make for both sides to resume compliance with the JCPOA.4Deirdre Shesgreen, “‘A Game of Chicken’: U.S. Holds Indirect Talks with Iran over Nuclear Deal amid Conflicting Political Pressure,” USA Today, April 6, 2021, https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/world/2021/04/06/iran-nuclear-deal-biden-administration-plans-indirect-talks-iran/4850338001/.

Hindering talks is the issue of synchronization: how and in what order each side will meet its obligations committed to in the JCPOA.5Parisa Hafezi and John Irish, “Analysis: Iran Nuclear Deal Rescue Needs More Time, Envoys Say Ahead of Fresh Talks,” Reuters, June 8, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/world/china/iran-nuclear-deal-rescue-needs-more-time-envoys-say-ahead-fresh-talks-2021-06-08/. Washington insists on a concession-for-concession framework whereby both sides return to compliance simultaneously, while Tehran demands the United States lift sanctions before it rolls back its nuclear activities in breach.6Peter Kenyon and Avie Schneider, “Biden Says U.S. Won’t Lift Sanctions before Iran Returns to Nuclear Deal,” NPR, February 7, 2021, https://www.npr.org/2021/02/07/965041827/irans-supreme-leader-u-s-must-lift-sanctions-before-any-return-to-nuclear-deal. The inauguration in August of Iran’s new president, Ebrahim Raisi, a hardliner and disciple of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, added to the difficulty.7Farnaz Fassihi, “A New President Takes Office in Iran, Solidifying Hard-Line Control,” New York Times, August 5, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/08/05/world/middleeast/iran-president-raisi-inaugurated.html.

Iran questions the United States’ ability to uphold a resumed agreement since it abrogated the original deal even though Iran was meeting its commitments. Even as Iran’s top nuclear negotiator, Ali Bagheri Kani, says talks will resume on November 29, the Raisi administration insists the United States guarantee it will not withdraw again (including under a future U.S. administration).8Patrick Sykes, Arsalan Shahla, and Nick Wadhams, “Iran Nuclear Talks to Resume amid Growing Doubts about a Deal,” Bloomberg, November 3, 2021, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-11-03/iran-says-nuclear-talks-will-resume-on-november-29-in-vienna; Patrick Wintour, “U.S. Must Guarantee It Will Not Leave Nuclear Deal Again, Says Iran,” Guardian, June 30, 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/jun/30/us-must-guarantee-it-will-not-leave-nuclear-deal-again-says-iran; “Iran Demands Assurance U.S. Will Not Pull Out of Nuclear Deal,” Voice of America, November 8, 2021, https://www.voanews.com/a/iran-demands-assurance-us-will-not-pull-out-of-nuclear-deal/6304424.html. After talks paused in June, Iran started up more advanced centrifuges and enriched more uranium at higher quality.

U.S. officials accuse Iran of stalling. Secretary Blinken warned in October the United States and Iran could reach a point when coming back into compliance with the JCPOA is no longer viable.9Kylie Atwood, “Blinken Says U.S. Is Prepared to Turn to ‘Other Options’ If Nuclear Diplomacy with Iran Fails,” CNN, October 13, 2021, https://www.cnn.com/2021/10/13/politics/blinken-israel-uae-iran-talks/index.html. The Biden administration is reviewing more punitive options, including new sanctions on networks transporting Iranian crude oil to China, Iran’s largest customer.10Benoit Faucon and Ian Talley, “U.S. Weighs New Sanctions on Iran’s Oil Sales to China If Nuclear Talks Fail,” Wall Street Journal, July 19, 2021, https://www.wsj.com/articles/u-s-weighs-new-sanctions-on-irans-oil-sales-to-china-if-nuclear-talks-fail-11626692402. Proponents of the ongoing escalation strategy advocate for legislation that triggers additional U.S. sanctions if Iran does not fulfill its part of the nuclear agreement by a specified date.11Mark Dubowitz, “Biden Paints Himself into a Corner on the Iran Nuclear Deal,” Wall Street Journal, September 28, 2021, https://www.wsj.com/articles/biden-iran-nuclear-deal-jcpoa-amir-abdollahian-tehran-sanctions-maximum-pressure-11632861521.

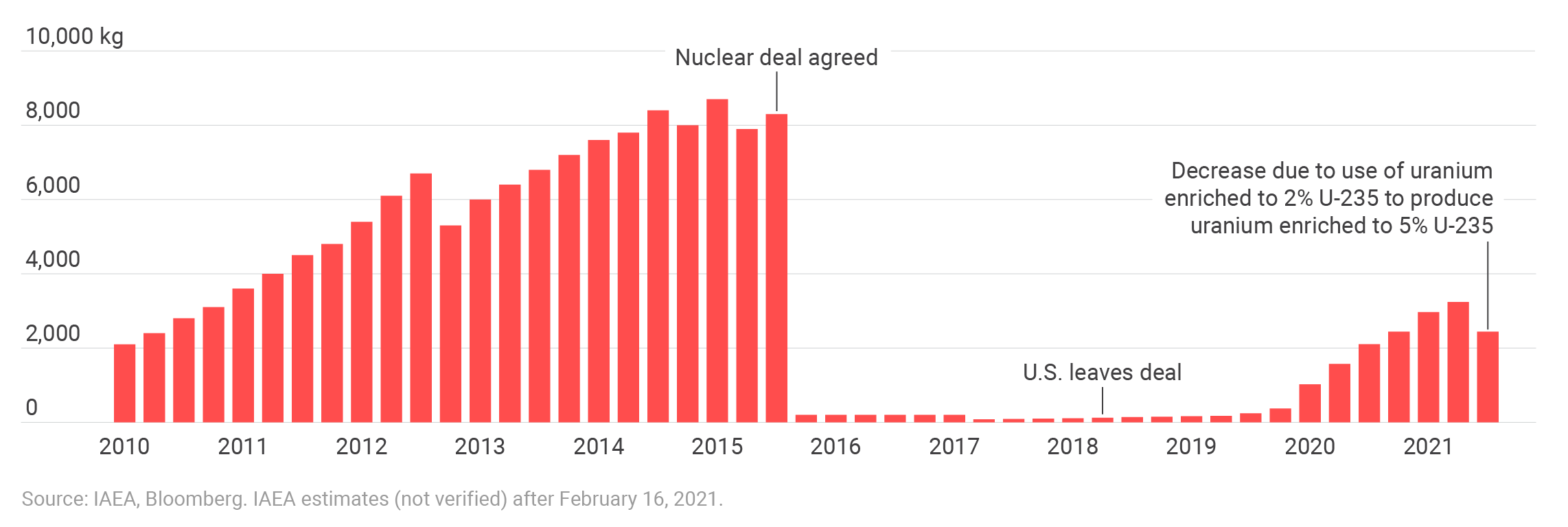

Iran’s enriched uranium stockpile

The JCPOA limited Iran’s enriched uranium stockpile to 202.8 kg, which Tehran began exceeding in 2019, one year after the U.S. withdrew from the agreement.

Iran’s position hardened because of pressure

President Trump’s decision to pull the United States out of the JCPOA and reimpose comprehensive economic sanctions on Iran is directly responsible for the current dilemma.12“Ceasing U.S. Participation in the JCPOA and Taking Additional Action to Counter Iran’s Malign Influence and Deny Iran All Paths to a Nuclear Weapon,” White House, May 8, 2018, https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/presidential-actions/ceasing-u-s-participation-jcpoa-taking-additional-action-counter-irans-malign-influence-deny-iran-paths-nuclear-weapon/. As explained in May 2018 by the then Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, the additional pressure aimed to force Tehran into a new set of negotiations about Iran’s conduct, of which its nuclear program was only a part. Secretary Pompeo listed 12 demands Iran must meet for the United States to lift sanctions: The Trump administration expected Iran to make a full account to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) on its prior nuclear work going back decades, stop all uranium enrichment, terminate its ballistic missile work, end support to its proxies in the Middle East, and withdraw Iranian forces from Syria, among other requirements. Until Iran’s government met those demands, sanctions on its economy would continue and, if necessary, accelerate.13“After the Deal: The New Iran Strategy, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s First Public Address on the Trump Administration’s Iran Strategy,” The Heritage Foundation, May 21, 2018, https://www.heritage.org/defense/event/after-the-deal-new-iran-strategy.

According to the architects of this escalation policy, financial distress on Iran’s economy would become so great that Iran would have no choice but to resume talks with the United States in a far weaker position.14Sean Illing, “Why Trump Is Right to Pull Out of the Iran Nuclear Deal,” Vox, May 8, 2018, https://www.vox.com/world/2018/5/8/17326650/iran-nuclear-deal-withdraw-trump-speech-goldberg-interview. Thus, the more strained Iran’s fiscal situation became, the more likely Iran’s leaders would offer deeper concessions on its nuclear program and its overall foreign policy. President Trump’s National Security Advisor John Bolton also argued economic sanctions could help promote regime change in Tehran.15John Bolton, “Beyond the Iran Nuclear Deal,” Wall Street Journal, January 15, 2018, https://www.wsj.com/articles/beyond-the-iran-nuclear-deal-1516044178.

This escalation policy misunderstands how states tend to respond to pressure. As John J. Mearsheimer of the University of Chicago has written, foreign pressure rarely compels states to surrender their core security interests—particularly when the state in question is weak and shares a neighborhood with committed adversaries.16John J. Mearsheimer, “Iran Is Rushing to Build a Nuclear Weapon—and Trump Can’t Stop It,” New York Times, July 1, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/01/opinion/iran-is-rushing-to-build-a-nuclear-weapon-and-trump-cant-stop-it.html. Iran is not exceptional. Iranian officials operate in a political system that, like many others, rewards policymakers and politicians for their nationalistic bona fides and discourages them from conceding to foreign pressure—particularly from the United States. Acceding to U.S. demands would expose Tehran to more exorbitant demands in the future.17Barry R. Posen, “Courting War,” Boston Review, March 3, 2020, https://bostonreview.net/war-security/barry-r-posen-courting-war.

The maximum pressure escalation strategy ignores this reality. Though sanctions harm Iran’s economy, it has not and is unlikely to result in the stated political outcomes sought by the policy.

Between 2018 and 2020, the United States enacted broad sanctions on Iranian sectors ranging from automobiles and metals to construction, mining, manufacturing, and textiles.18Kenneth Katzman, “Iran Sanctions,” Congressional Research Service (RS20871), updated April 6, 2021, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/details?prodcode=RS20871. In 2020 alone, Iranian-linked entities and individuals comprised more than 40 percent of the Trump administration’s total sanctions designations.19Sam Dorshimer and Francis Shin, “Sanctions by the Numbers: 2020 Year in Review,” CNAS, January 14, 2021, https://www.cnas.org/publications/reports/sanctions-by-the-numbers-2020. Secondary U.S. sanctions on Iran’s energy sector, which penalize third-party nationals who import, finance, or transport Iranian crude oil and natural gas, diminished Tehran’s export capacity. The Trump administration’s cancellation of Iranian oil waivers to China, India, South Korea, and Japan in 2019 took hundreds of thousands of barrels of Iranian crude offline.20Dan De Luce and Abigail Williams, “Trump Administration Moves to Cut Off Iranian Oil Exports,” NBC News, April 22, 2019, https://www.nbcnews.com/news/amp/ncna997006. Iran’s total crude exports decreased from 2.5 million BPD in 2017 to 400,000 BPD at the end of 2020—an 84 percent reduction.21“Iran’s Crude Oil Production Fell to an Almost 40-Year Low in 2020,” U.S. Energy Information Administration, August 12, 2021, https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=49116.

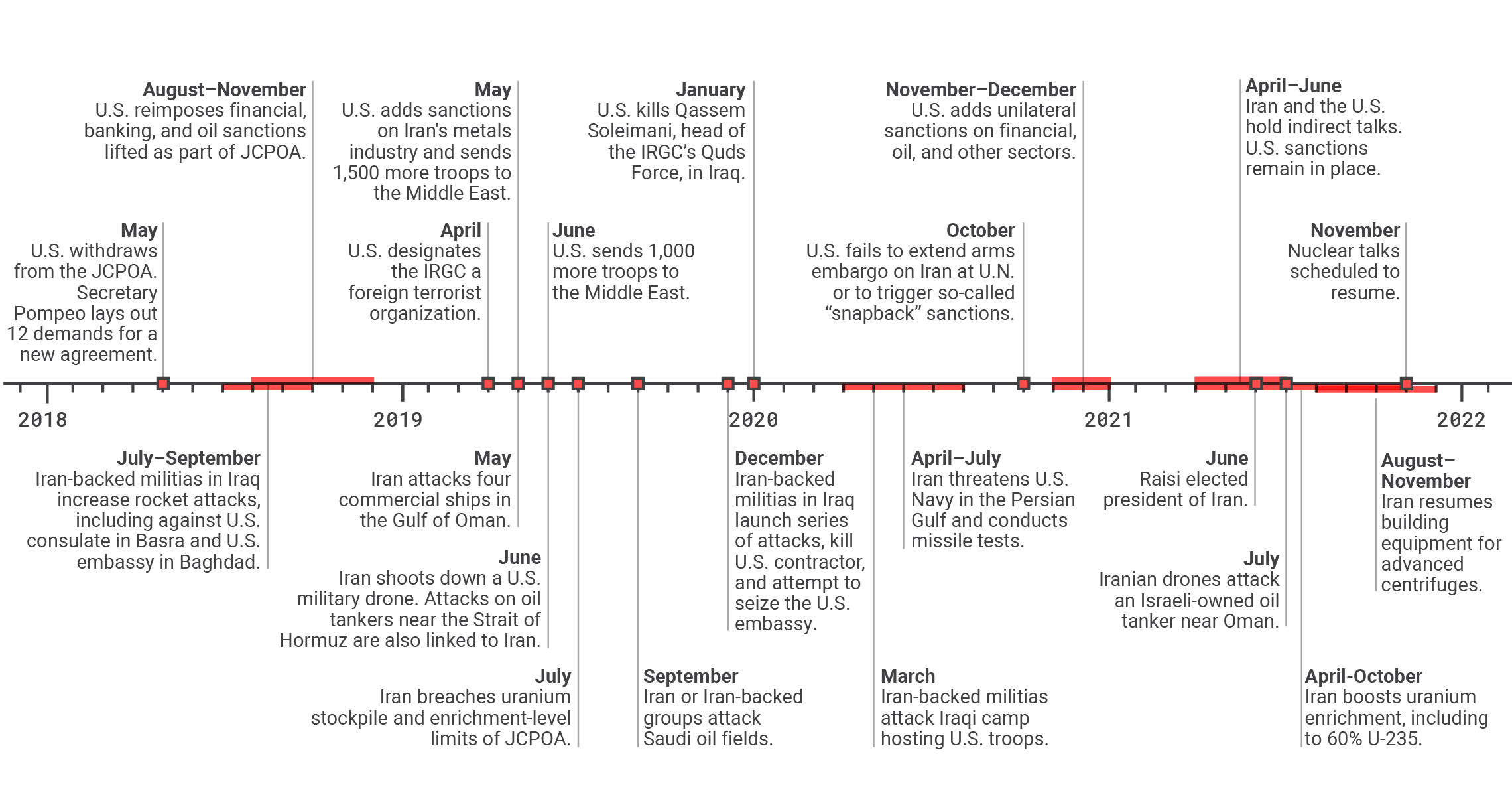

Timeline of maximum pressure strategy

The pressure strategy begun by President Trump and carried forward by President Biden increased confrontation between the U.S. and Iran beyond Tehran’s nuclear program.

Predictably, Iran countered U.S. pressure tactics with pressure of its own. Because other countries could no longer trade with or invest in Iran, Tehran had less incentive to comply with uranium enrichment caps and restrictions on centrifuge development. In May 2019, a year after the United States left the JCPOA, Iran announced it would “reduce compliance” with some provisions of the deal.22Patrick Wintour, “Iran Announces Partial Withdrawal from Nuclear Deal,” Guardian, May 8, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/may/07/iran-to-announces-partial-withdrawal-from-nuclear-deal; Rick Gladstone, “Iran Appears Ready to Reduce Compliance with Nuclear Deal,” New York Times, May 6, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/06/world/middleeast/iran-trump-nuclear-deal.html. In July 2019, Iran breached the JCPOA by surpassing the ceiling on the amount of low enriched uranium it could stockpile under the deal.23“Iran’s Breaches of the Nuclear Deal,” The Iran Primer, United States Institute of Peace, updated July 7, 2021, https://iranprimer.usip.org/blog/2019/oct/02/iran’s-breaches-nuclear-deal. Two months later, the Iranian government announced it would forgo limits on nuclear research and use an array of advanced centrifuges, including multiple IR-6s, which enrich uranium 10 times faster than the IR-1 type allowed under the JCPOA.24Nasser Karimi and Jon Gambrell “Iran Uses Advanced Centrifuges, Threatens Higher Enrichment,” Associated Press, September 7, 2019, https://apnews.com/article/europe-donald-trump-ap-top-news-persian-gulf-tensions-tehran-7e896f8a1b0c40769b54ed4f98a0f5e6. On January 4, 2021, Iran resumed enriching uranium to 20 percent, another abrogation of the nuclear agreement.25Less than one percent of uranium found in nature is the fissionable isotope U-235. Weapons-grade uranium must be enriched to 90 percent U-235. See Eric Cunningham and Kareem Fahim, “Iran Begins Enriching Uranium to 20 Percent in Breach of Nuclear Deal,” Washington Post, January 4, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/middle_east/iran-nuclear-uranium-enrichment/2021/01/04/588949be-4e76-11eb-a1f5-fdaf28cfca90_story.html. By April, Iran began enriching to 60 percent. As the IAEA assessed in a recent report, Iran’s enriched uranium stockpile exceeds 2,440 kg, more than 10 times what the JCPOA permits.26“Verification and Monitoring in the Islamic Republic of Iran in Light of United Nations Security Council Resolution 2231 (2015),” International Atomic Energy Agency (GOV/2021/39), September 7, 2021, https://www.iaea.org/sites/default/files/21/09/gov2021-39.pdf. In recent weeks, Iranian officials said the heavy water reactor in Arak, the construction of which was halted under the JCPOA, may soon forge ahead to completion. If finished, it would give Iran a plutonium pathway to a nuclear bomb. Iran is much closer to a nuclear bomb today than it was before the United States withdrew from the JCPOA.27David E. Sanger and William J. Broad, “Iran Nears an Atomic Milestone,” New York Times, September 13, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/09/13/us/politics/iran-nuclear-fuel-enrichment.html.

The current policy’s record of failure extends to non-nuclear issues. Since the United States pursued this escalation strategy, Tehran grew more belligerent in its regional foreign policy. Unable to market its oil to foreign buyers, Iran attempted to limit its neighbors’ export capacity. Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) attacked and damaged civilian tankers and cargo ships in the Persian Gulf. In May 2019, a month after the United States terminated waivers for Iran’s top crude buyers and designated the IRGC a Foreign Terrorist Organization (FTO), mines likely placed by Iran damaged four oil vessels.28Vivian Yee, “Claim of Attacks on 4 Oil Vessels Raises Tensions in Middle East,” New York Times, May 13, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/13/world/middleeast/saudi-arabia-oil-tanker-sabotage.html. A month later, U.S. Navy investigators held Iran responsible for mine attacks on two Japanese oil tankers in the Strait of Hormuz.29“Japan Ship Attacked Near Strait of Hormuz, U.S. Blames Iran,” Kyodo News, June 13, 2019, https://english.kyodonews.net/news/2019/06/fe23a1c7a166-urgent-japanese-ship-attacked-in-strait-of-hormuz-minister-seko.html. The IRGC seized another three oil tankers (one British, one Liberian, and one Iraqi) in July and August 2019.30“Iran Seizes British Tanker in Strait of Hormuz,” BBC, July 20, 2019, https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-49053383. And in September of the same year, Iran attacked Saudi Arabia’s Abqaiq facility with cruise missiles and drones, interrupting about half of Saudi oil production for several days.31Eric Schmitt, Farnaz Fassihi, and David D. Kirkpatrick, “Saudi Oil Attack Photos Implicate Iran, U.S. Says; Trump Hints at Military Action,” New York Times, September 15, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/15/world/middleeast/iran-us-saudi-arabia-attack.html.

Pressure also has a military dimension. Approximately 20,000 additional U.S. troops were deployed to the Middle East between May 2019 and January 2020, bringing the total U.S. military presence in the region to more than 80,000.32Lolita C. Baldor, “U.S. General Says Troop Surge in Middle East May Not End Soon,” Associated Press, January 23, 2020, https://apnews.com/article/2208d8645ac0437024ac71c06fcfb8e1. In May 2019, the Trump administration ordered the deployment of a carrier strike group, complete with a detachment of B-52 bombers.33Edward Wong, “Citing Iranian Threat, U.S. Sends Carrier Group and Bombers to Persian Gulf,” New York Times, May 5, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/05/world/middleeast/us-iran-military-threat-.html. Yet a larger presence meant greater risk of Iranian or Iranian-linked retaliation.34Mike Sweeney, “A Plan for U.S. Withdrawal from the Middle East,” Defense Priorities, December 2020, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/a-plan-for-us-withdrawal-from-the-middle-east. Shia militias in Iraq and Syria, the most powerful of which receive financing from Iran, fired rockets at U.S. military sites in both countries. Defense Intelligence Agency reports assess Iranian-backed militias in Iraq attacked U.S. targets more than 300 times between late 2019 (when U.S. sanctions were beginning to have full effect on Iran’s economy) and April 2021.35Scott Berrier, “Statement for the Record: Worldwide Threat Assessment,” Defense Intelligence Agency, April 29, 2021, https://www.dia.mil/News/Speeches-and-Testimonies/Article-View/Article/2590462/statement-for-the-record-worldwide-threat-assessment/. Some of those attacks killed Americans and prompted U.S. military retaliation—a cycle of escalation that reached a pinnacle on January 3, 2021, when a U.S. drone killed IRGC Gen. Qassem Soleimani, head of Iran’s Quds force, outside the Baghdad airport. Iran struck two U.S. bases in Iraq with ballistic missiles days later, leaving more than 100 U.S. military personnel suffering from traumatic brain injuries.36Diana Stancy Correll, “109 U.S. Troops Diagnosed with TBI after Iran Missile Barrage Says Pentagon in Latest Update,” Military Times, February 10, 2020, https://www.militarytimes.com/news/your-military/2020/02/10/more-than-100-us-troops-diagnosed-with-tbi-after-irans-attack-at-al-asad-report.

The strategy is causing problems beyond the Middle East as well. Seeking to preserve economic ties with Iran, Europe created a euro-denominated payment system (INSTEX) to get around U.S. sanctions. European countries and Iran completed a first deal of medical goods on the financial channel in March 2020, but nothing of note since. Despite INSTEX failing to take off, Europe’s challenge to the U.S.-led financial system offers other countries a precedent to undermine the power of U.S. sanctions and the U.S. dollar as the world’s reserve currency.37Enea Gjoza, “Counting the Cost of Financial Warfare,” Defense Priorities, November 2019, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/counting-the-cost-of-financial-warfare.

Do not double down on a failed strategy

Biden administration officials acknowledge the ongoing pressure strategy is counterproductive to U.S. goals in the Middle East and beyond. In October 2019, Jake Sullivan and William Burns, now President Biden’s national security advisor and CIA director, respectively, wrote the United States leaving the JCPOA and instituting secondary sanctions on Iran failed to push Iran into softening its negotiating position.38William J. Burns and Jake Sullivan, “It’s Time to Talk to Iran,” New York Times, October 14, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/14/opinion/iran-nuclear-deal.html. Earlier this year, Robert Malley, U.S. special envoy to the Iran negotiations, said the pressure campaign “failed miserably and hurt U.S. interests.”39The Mehdi Hasan Show, Twitter, July 25, 2021, 9:04 p.m., https://twitter.com/MehdiHasanShow/status/1419463490096467969?s=20.

Despite rhetoric of departure from the Trump administration, the Biden administration continues the same pressure strategy. The Biden administration is so far unwilling to spend political capital to abandon the failed policy. But the politics would be worse if the United States and Iran stumbled into a pointless, costly war. Current U.S. policy increases this risk. The United States stations tens of thousands of troops in the Middle East (mostly on large bases in the Persian Gulf, susceptible to Iranian ballistic and cruise missiles) and conducts frequent navigational patrols which produce tense encounters with Iranian naval forces.40Lara Seligman, “U.S. Navy Fires Warning Shots at Iranian Gunboats in Persian Gulf,” Politico, April 27, 2021, https://www.politico.com/news/2021/04/27/us-navy-iranian-gunboats-escalation-484813. Shia militias funded and influenced by Iran continue to attack the approximately 3,500 U.S. troops deployed in Iraq and Syria with drones and rockets—as recently as October 20, five drones armed with explosives targeted the small U.S. outpost in Syria’s Al-Tanf.41Lolita C. Baldor and Robert Burns, “Officials: Iran behind Drone Attack on U.S. Base in Syria,” Associated Press, https://apnews.com/article/middle-east-iran-syria-lebanon-tehran-e4410d13c73f45128d9d3a09e5b8e81d. The status quo increases the probability of a clash that escalates into a more violent conflagration.

The United States faces two choices: (1) continue to enforce the same strategy that makes negotiations more difficult and risks war or (2) unwind this failed policy, create space to advance diplomacy, and avoid a needless war. The United States risks nothing by first removing some pressure—doing so would provide domestic political cover for Iran to resume compliance, and any failure on its part could be easily undone by reimposing some sanctions in connection with a realistic strategy. Specifically, the United States should:

- Reinstate some of the oil sanction waivers rescinded under the Trump administration that would allow Iran to legally export a limited amount of crude to buyers in Europe, South Korea, Japan, and India (U.S. allies and strategic partners). The profits from these sales could be held in escrow and used to help Iran engage in commerce.

- Permit Iran to access a portion of its foreign reserves, which amounted to roughly $115 billion as of last year, now locked in overseas accounts due to U.S. banking sanctions.42“Regional Economic Outlook: Middle East and Central Asia,” International Monetary Fund, October 2020, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/REO/MECA/Issues/2020/10/14/regional-economic-outlook-menap-cca#stats. Approximately $7 billion of Iran’s money is frozen in South Korean banks; in order to add momentum to nuclear diplomacy, the United States could tell the South Korean government that Iran is allowed to use some of this money to finance debt payments or imports for non-military items.43“Korea-Iran Row Worsens over Oil Billions Frozen by U.S. Sanctions,” Korea Times, updated October 9, 2021, https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/nation/2021/10/120_316726.html.

While the United States should move first, it should do so having received indications, presumably kept private, that Iran will respond with concrete nuclear concessions—suspending production of enriched uranium above 5 percent or exporting a portion of its stockpile of enriched uranium, for example. A step-by-step process initiated by the United States is the most likely sequence to secure a mutual return by both the United States and Iran to their JCPOA commitments.

If Iran refuses to engage, the United States need not overreact or double down on failed sanctions or other coercive measures. Diplomacy should continue regardless of whether the nuclear negotiations succeed or fail. Regular engagement is not a concession; the United States maintains relations with most states in the Middle East, many of which are just as autocratic and destabilizing as Iran. This is not because the United States accepts their conduct or agrees with their policies, but rather because contact is a prerequisite for constructive statecraft to advance U.S. interests and can prevent miscalculation. With Iran, diplomatic relations are important since the alternatives—sanctions, isolation, or preventive war—are ineffective or not worth the risks.

Use diplomacy to foreclose an unnecessary war

U.S. interests in the Middle East are narrow: (1) defend against anti-U.S. terrorist threats and (2) prevent significant, long-term disruptions to the global energy supply. The United States will remain secure and capable of fulfilling these interests no matter the status of the JCPOA. The actual threat Iran poses to the United States and its interests is minimal and takes little effort to thwart.

Iran is a middling power in the Middle East. With a gross domestic product of $191 billion, Iran’s economy is about the size of Nevada’s.44“GDP (current US$)—Iran, Islamic Republic,” World Bank, accessed October 26,2021, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?locations=IR. Iran’s conventional ground forces are untested in battle since the Iran-Iraq War in the 1980s.45Ariane M. Tabatabai, Nathan Chandler, Bryan Frederick, and Jennifer Kavanagh, “Iran’s Military Interventions: Patterns, Drivers, and Signposts,” Rand Corporation (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2021), https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA444-2.html. While the Iranian missile program is improving in range and sophistication, its air force is antiquated and susceptible to modern air defense systems.46“Iran Military Power,” Defense Intelligence Agency, August 2019, https://www.dia.mil/Portals/110/Images/News/Military_Powers_Publications/Iran_Military_Power_LR.pdf. Iran’s defense budget was $14.1 billion in 2020, nearly five times smaller than what Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates spent combined.47Haena Jo, “Can the U.A.E. Emerge as a Leading Global Defense Supplier?” Defense News, February 15, 2021, https://www.defensenews.com/digital-show-dailies/idex/2021/02/15/can-the-uae-emerge-as-a-leading-global-defense-supplier/. It is highly unlikely the Iranian military can close the Strait of Hormuz, through which one-third of worldwide sea-bound crude oil flows—and given Iran’s dependence on oil export revenue to finance its budget, Tehran has no incentive to do so.48Eugene Gholz and Daryl G. Press, “Protecting ‘The Prize’: Oil and the U.S. National Interest,” Security Studies Volume 19, Issue 3 (2010): 453–485. Iran’s chances of dominating the Persian Gulf’s oil supply are near zero.49Justin Logan, “The Case for Withdrawing from the Middle East,” Defense Priorities, September 2020, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/the-case-for-withdrawing-from-the-middle-east. Outside of several non-state proxies and a beleaguered Syrian government that relies on Tehran for everything from military manpower to fuel subsidies, Iran has no allies to speak of and is surrounded by competitors, adversaries, and weak states.

Even with a nuclear program capable of producing a weapon, Iran may stop short of building a nuclear bomb due to the practical constraints of operating a nuclear arsenal. An Iranian nuclear arsenal, however small, could spur nuclear proliferation in the region as Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and Egypt seek to attain nuclear deterrents of their own.50Mike Sweeney, “Considering the Utility of an Iranian Bomb,” Defense Priorities, September 2021, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/considering-the-utility-of-an-iranian-nuclear-bomb. If Iran decides to build a bomb, the United States should implement a strategy of deterrence and crisis management, just as it has with other adversarial nuclear powers.

As many predicted, maximum pressure against Iran failed in every respect. Iran is enriching more uranium to higher levels, IAEA monitoring is curtailed, and Tehran’s foreign policy is more belligerent.51Kelsey Davenport and Julia Masterson, “IAEA Report on Iran Raises Serious Concerns about Monitoring,” Arms Control Association, September 8, 2021, https://www.armscontrol.org/blog/2021-09-08/iaea-report-iran-raises-serious-concerns. The Biden administration’s decision to negotiate with Iran is a step in the right direction. But practical diplomacy from the U.S. side could keep the JCPOA intact and reduce the risks of a war that would drain U.S. resources, trap the U.S. military in the Middle East, and distract from higher priorities.

Endnotes

- 1“President Donald J. Trump Is Ending United States Participation in an Unacceptable Iran Deal,” White House, May 8, 2018, https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/briefings-statements/president-donald-j-trump-ending-united-states-participation-unacceptable-iran-deal/.

- 2“Secretary Antony J. Blinken at a Press Availability,” U.S. Department of State, March 24, 2021, https://www.state.gov/secretary-antony-j-blinken-at-a-press-availability-3.

- 3Ellen Knickmeyer and Raf Casert, “‘First Step:’ U.S., Iran to Begin Indirect Nuclear-Limit Talks,” Associated Press, April 2, 2021, https://apnews.com/article/us-iran-indirect-talks-nuclear-program-a6558ac21b600cb7a3c8542f18a7aece.

- 4Deirdre Shesgreen, “‘A Game of Chicken’: U.S. Holds Indirect Talks with Iran over Nuclear Deal amid Conflicting Political Pressure,” USA Today, April 6, 2021, https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/world/2021/04/06/iran-nuclear-deal-biden-administration-plans-indirect-talks-iran/4850338001/.

- 5Parisa Hafezi and John Irish, “Analysis: Iran Nuclear Deal Rescue Needs More Time, Envoys Say Ahead of Fresh Talks,” Reuters, June 8, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/world/china/iran-nuclear-deal-rescue-needs-more-time-envoys-say-ahead-fresh-talks-2021-06-08/.

- 6Peter Kenyon and Avie Schneider, “Biden Says U.S. Won’t Lift Sanctions before Iran Returns to Nuclear Deal,” NPR, February 7, 2021, https://www.npr.org/2021/02/07/965041827/irans-supreme-leader-u-s-must-lift-sanctions-before-any-return-to-nuclear-deal.

- 7Farnaz Fassihi, “A New President Takes Office in Iran, Solidifying Hard-Line Control,” New York Times, August 5, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/08/05/world/middleeast/iran-president-raisi-inaugurated.html.

- 8Patrick Sykes, Arsalan Shahla, and Nick Wadhams, “Iran Nuclear Talks to Resume amid Growing Doubts about a Deal,” Bloomberg, November 3, 2021, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-11-03/iran-says-nuclear-talks-will-resume-on-november-29-in-vienna; Patrick Wintour, “U.S. Must Guarantee It Will Not Leave Nuclear Deal Again, Says Iran,” Guardian, June 30, 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/jun/30/us-must-guarantee-it-will-not-leave-nuclear-deal-again-says-iran; “Iran Demands Assurance U.S. Will Not Pull Out of Nuclear Deal,” Voice of America, November 8, 2021, https://www.voanews.com/a/iran-demands-assurance-us-will-not-pull-out-of-nuclear-deal/6304424.html.

- 9Kylie Atwood, “Blinken Says U.S. Is Prepared to Turn to ‘Other Options’ If Nuclear Diplomacy with Iran Fails,” CNN, October 13, 2021, https://www.cnn.com/2021/10/13/politics/blinken-israel-uae-iran-talks/index.html.

- 10Benoit Faucon and Ian Talley, “U.S. Weighs New Sanctions on Iran’s Oil Sales to China If Nuclear Talks Fail,” Wall Street Journal, July 19, 2021, https://www.wsj.com/articles/u-s-weighs-new-sanctions-on-irans-oil-sales-to-china-if-nuclear-talks-fail-11626692402.

- 11Mark Dubowitz, “Biden Paints Himself into a Corner on the Iran Nuclear Deal,” Wall Street Journal, September 28, 2021, https://www.wsj.com/articles/biden-iran-nuclear-deal-jcpoa-amir-abdollahian-tehran-sanctions-maximum-pressure-11632861521.

- 12“Ceasing U.S. Participation in the JCPOA and Taking Additional Action to Counter Iran’s Malign Influence and Deny Iran All Paths to a Nuclear Weapon,” White House, May 8, 2018, https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/presidential-actions/ceasing-u-s-participation-jcpoa-taking-additional-action-counter-irans-malign-influence-deny-iran-paths-nuclear-weapon/.

- 13“After the Deal: The New Iran Strategy, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s First Public Address on the Trump Administration’s Iran Strategy,” The Heritage Foundation, May 21, 2018, https://www.heritage.org/defense/event/after-the-deal-new-iran-strategy.

- 14Sean Illing, “Why Trump Is Right to Pull Out of the Iran Nuclear Deal,” Vox, May 8, 2018, https://www.vox.com/world/2018/5/8/17326650/iran-nuclear-deal-withdraw-trump-speech-goldberg-interview.

- 15John Bolton, “Beyond the Iran Nuclear Deal,” Wall Street Journal, January 15, 2018, https://www.wsj.com/articles/beyond-the-iran-nuclear-deal-1516044178.

- 16John J. Mearsheimer, “Iran Is Rushing to Build a Nuclear Weapon—and Trump Can’t Stop It,” New York Times, July 1, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/01/opinion/iran-is-rushing-to-build-a-nuclear-weapon-and-trump-cant-stop-it.html.

- 17Barry R. Posen, “Courting War,” Boston Review, March 3, 2020, https://bostonreview.net/war-security/barry-r-posen-courting-war.

- 18Kenneth Katzman, “Iran Sanctions,” Congressional Research Service (RS20871), updated April 6, 2021, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/details?prodcode=RS20871.

- 19Sam Dorshimer and Francis Shin, “Sanctions by the Numbers: 2020 Year in Review,” CNAS, January 14, 2021, https://www.cnas.org/publications/reports/sanctions-by-the-numbers-2020.

- 20Dan De Luce and Abigail Williams, “Trump Administration Moves to Cut Off Iranian Oil Exports,” NBC News, April 22, 2019, https://www.nbcnews.com/news/amp/ncna997006.

- 21“Iran’s Crude Oil Production Fell to an Almost 40-Year Low in 2020,” U.S. Energy Information Administration, August 12, 2021, https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=49116.

- 22Patrick Wintour, “Iran Announces Partial Withdrawal from Nuclear Deal,” Guardian, May 8, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/may/07/iran-to-announces-partial-withdrawal-from-nuclear-deal; Rick Gladstone, “Iran Appears Ready to Reduce Compliance with Nuclear Deal,” New York Times, May 6, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/06/world/middleeast/iran-trump-nuclear-deal.html.

- 23“Iran’s Breaches of the Nuclear Deal,” The Iran Primer, United States Institute of Peace, updated July 7, 2021, https://iranprimer.usip.org/blog/2019/oct/02/iran’s-breaches-nuclear-deal.

- 24Nasser Karimi and Jon Gambrell “Iran Uses Advanced Centrifuges, Threatens Higher Enrichment,” Associated Press, September 7, 2019, https://apnews.com/article/europe-donald-trump-ap-top-news-persian-gulf-tensions-tehran-7e896f8a1b0c40769b54ed4f98a0f5e6.

- 25Less than one percent of uranium found in nature is the fissionable isotope U-235. Weapons-grade uranium must be enriched to 90 percent U-235. See Eric Cunningham and Kareem Fahim, “Iran Begins Enriching Uranium to 20 Percent in Breach of Nuclear Deal,” Washington Post, January 4, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/middle_east/iran-nuclear-uranium-enrichment/2021/01/04/588949be-4e76-11eb-a1f5-fdaf28cfca90_story.html.

- 26“Verification and Monitoring in the Islamic Republic of Iran in Light of United Nations Security Council Resolution 2231 (2015),” International Atomic Energy Agency (GOV/2021/39), September 7, 2021, https://www.iaea.org/sites/default/files/21/09/gov2021-39.pdf.

- 27David E. Sanger and William J. Broad, “Iran Nears an Atomic Milestone,” New York Times, September 13, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/09/13/us/politics/iran-nuclear-fuel-enrichment.html.

- 28Vivian Yee, “Claim of Attacks on 4 Oil Vessels Raises Tensions in Middle East,” New York Times, May 13, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/13/world/middleeast/saudi-arabia-oil-tanker-sabotage.html.

- 29“Japan Ship Attacked Near Strait of Hormuz, U.S. Blames Iran,” Kyodo News, June 13, 2019, https://english.kyodonews.net/news/2019/06/fe23a1c7a166-urgent-japanese-ship-attacked-in-strait-of-hormuz-minister-seko.html.

- 30“Iran Seizes British Tanker in Strait of Hormuz,” BBC, July 20, 2019, https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-49053383.

- 31Eric Schmitt, Farnaz Fassihi, and David D. Kirkpatrick, “Saudi Oil Attack Photos Implicate Iran, U.S. Says; Trump Hints at Military Action,” New York Times, September 15, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/15/world/middleeast/iran-us-saudi-arabia-attack.html.

- 32Lolita C. Baldor, “U.S. General Says Troop Surge in Middle East May Not End Soon,” Associated Press, January 23, 2020, https://apnews.com/article/2208d8645ac0437024ac71c06fcfb8e1.

- 33Edward Wong, “Citing Iranian Threat, U.S. Sends Carrier Group and Bombers to Persian Gulf,” New York Times, May 5, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/05/world/middleeast/us-iran-military-threat-.html.

- 34Mike Sweeney, “A Plan for U.S. Withdrawal from the Middle East,” Defense Priorities, December 2020, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/a-plan-for-us-withdrawal-from-the-middle-east.

- 35Scott Berrier, “Statement for the Record: Worldwide Threat Assessment,” Defense Intelligence Agency, April 29, 2021, https://www.dia.mil/News/Speeches-and-Testimonies/Article-View/Article/2590462/statement-for-the-record-worldwide-threat-assessment/.

- 36Diana Stancy Correll, “109 U.S. Troops Diagnosed with TBI after Iran Missile Barrage Says Pentagon in Latest Update,” Military Times, February 10, 2020, https://www.militarytimes.com/news/your-military/2020/02/10/more-than-100-us-troops-diagnosed-with-tbi-after-irans-attack-at-al-asad-report.

- 37Enea Gjoza, “Counting the Cost of Financial Warfare,” Defense Priorities, November 2019, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/counting-the-cost-of-financial-warfare.

- 38William J. Burns and Jake Sullivan, “It’s Time to Talk to Iran,” New York Times, October 14, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/14/opinion/iran-nuclear-deal.html.

- 39The Mehdi Hasan Show, Twitter, July 25, 2021, 9:04 p.m., https://twitter.com/MehdiHasanShow/status/1419463490096467969?s=20.

- 40Lara Seligman, “U.S. Navy Fires Warning Shots at Iranian Gunboats in Persian Gulf,” Politico, April 27, 2021, https://www.politico.com/news/2021/04/27/us-navy-iranian-gunboats-escalation-484813.

- 41Lolita C. Baldor and Robert Burns, “Officials: Iran behind Drone Attack on U.S. Base in Syria,” Associated Press, https://apnews.com/article/middle-east-iran-syria-lebanon-tehran-e4410d13c73f45128d9d3a09e5b8e81d.

- 42“Regional Economic Outlook: Middle East and Central Asia,” International Monetary Fund, October 2020, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/REO/MECA/Issues/2020/10/14/regional-economic-outlook-menap-cca#stats.

- 43“Korea-Iran Row Worsens over Oil Billions Frozen by U.S. Sanctions,” Korea Times, updated October 9, 2021, https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/nation/2021/10/120_316726.html.

- 44“GDP (current US$)—Iran, Islamic Republic,” World Bank, accessed October 26,2021, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?locations=IR.

- 45Ariane M. Tabatabai, Nathan Chandler, Bryan Frederick, and Jennifer Kavanagh, “Iran’s Military Interventions: Patterns, Drivers, and Signposts,” Rand Corporation (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2021), https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA444-2.html.

- 46“Iran Military Power,” Defense Intelligence Agency, August 2019, https://www.dia.mil/Portals/110/Images/News/Military_Powers_Publications/Iran_Military_Power_LR.pdf.

- 47Haena Jo, “Can the U.A.E. Emerge as a Leading Global Defense Supplier?” Defense News, February 15, 2021, https://www.defensenews.com/digital-show-dailies/idex/2021/02/15/can-the-uae-emerge-as-a-leading-global-defense-supplier/.

- 48Eugene Gholz and Daryl G. Press, “Protecting ‘The Prize’: Oil and the U.S. National Interest,” Security Studies Volume 19, Issue 3 (2010): 453–485.

- 49Justin Logan, “The Case for Withdrawing from the Middle East,” Defense Priorities, September 2020, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/the-case-for-withdrawing-from-the-middle-east.

- 50Mike Sweeney, “Considering the Utility of an Iranian Bomb,” Defense Priorities, September 2021, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/considering-the-utility-of-an-iranian-nuclear-bomb.

- 51Kelsey Davenport and Julia Masterson, “IAEA Report on Iran Raises Serious Concerns about Monitoring,” Arms Control Association, September 8, 2021, https://www.armscontrol.org/blog/2021-09-08/iaea-report-iran-raises-serious-concerns.

More on Middle East

By Jennifer Kavanagh and Dan Caldwell

July 9, 2025

Featuring Rosemary Kelanic and Jennifer Kavanagh

June 30, 2025

Events on Middle East