Key points

- China’s rapid, multi-decade economic growth has transformed it into a great power, allowing it to pursue its interests more assertively in Asia and globally. But China’s growing strength does not necessitate military conflict with the United States.

- Nuclear deterrents, the great distance between the two nations, and U.S.-China trade interdependence limit potential military confrontation.

- It is nearly impossible for China to become a hegemonic power that dominates Eurasia because it is surrounded by major powers, nuclear states, and geography favoring defenders.

- China’s military modernization has largely focused on internal control and defensive capabilities.

- The primary U.S. security goal in East Asia—preserving the territorial integrity of U.S. allies—is best achieved by encouraging and helping allies better fortify themselves through (U.S.-provided if necessary) anti-access/area-denial (A2/AD) technology.

China is a great power and will inevitably behave as such

Great powers traditionally expand their political influence, increase their capacity to defend themselves against other great powers, and seek to shape international institutions to their advantage. China has predictably taken similar steps as it has grown into the world’s second largest economy.1Andrea Willige, “The World’s Top Economy: The U.S. vs China in Five Charts,” World Economic Forum, December 5, 2016, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/12/the-world-s-top-economy-the-us-vs-china-in-five-charts/. China is a great power with a large economy, capable military, strong industrial base, and extensive diplomatic ties. This gives it considerable influence in Asia and, to a lesser extent, the international system.

Some policymakers fear China could become a formidable strategic competitor for the U.S.—and that China’s continued economic growth might allow it eventually to dominate Asia, politically and economically, and potentially challenge U.S. military dominance there. It is therefore prudent to pay close attention to China and monitor its activities in all realms. It is crucial to note, however, that for reasons discussed below, China’s economic and political elevation into top-tier status should not automatically elicit fear in the West, nor does it portend a future military clash with the United States.

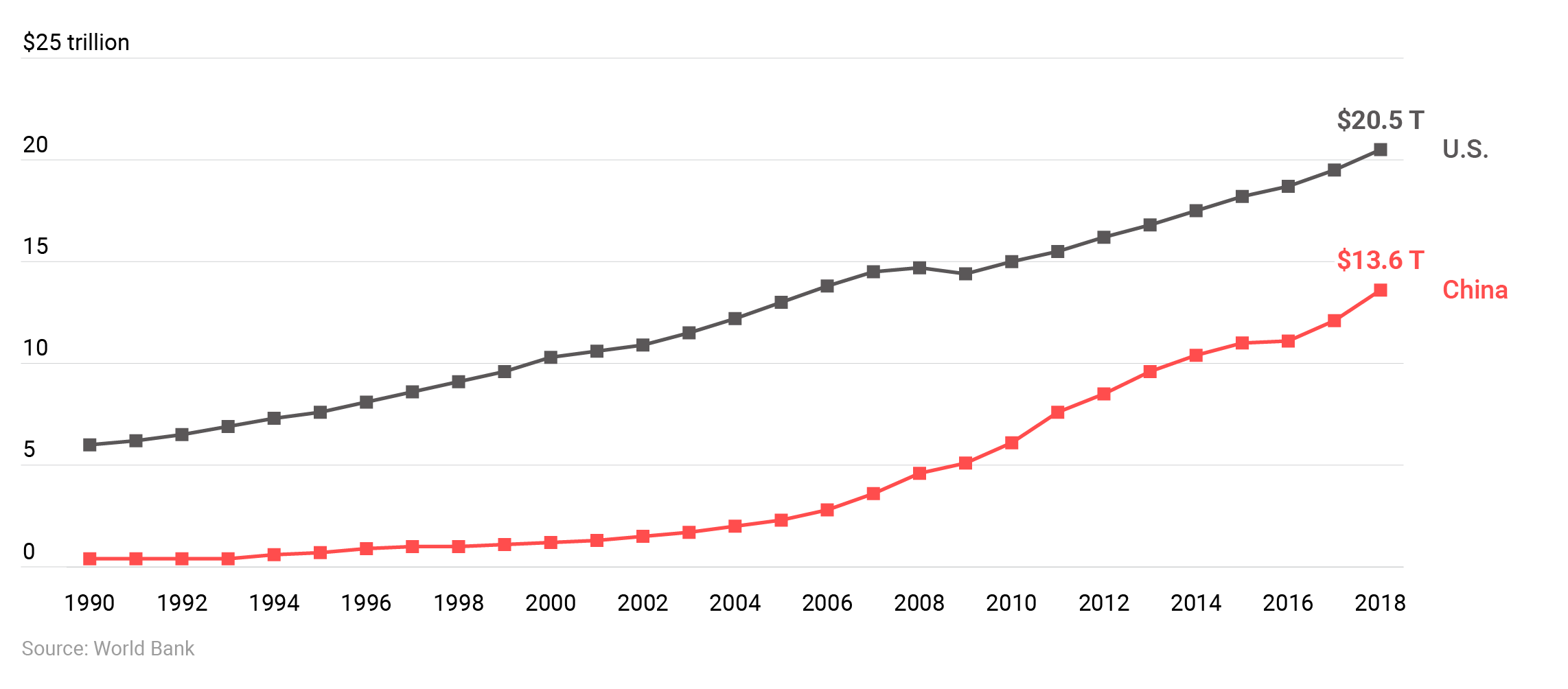

GDP of the U.S. and China from 1990–2018

Though recently slowing, China’s economic growth since 1990 has reduced the wealth gap with the U.S.

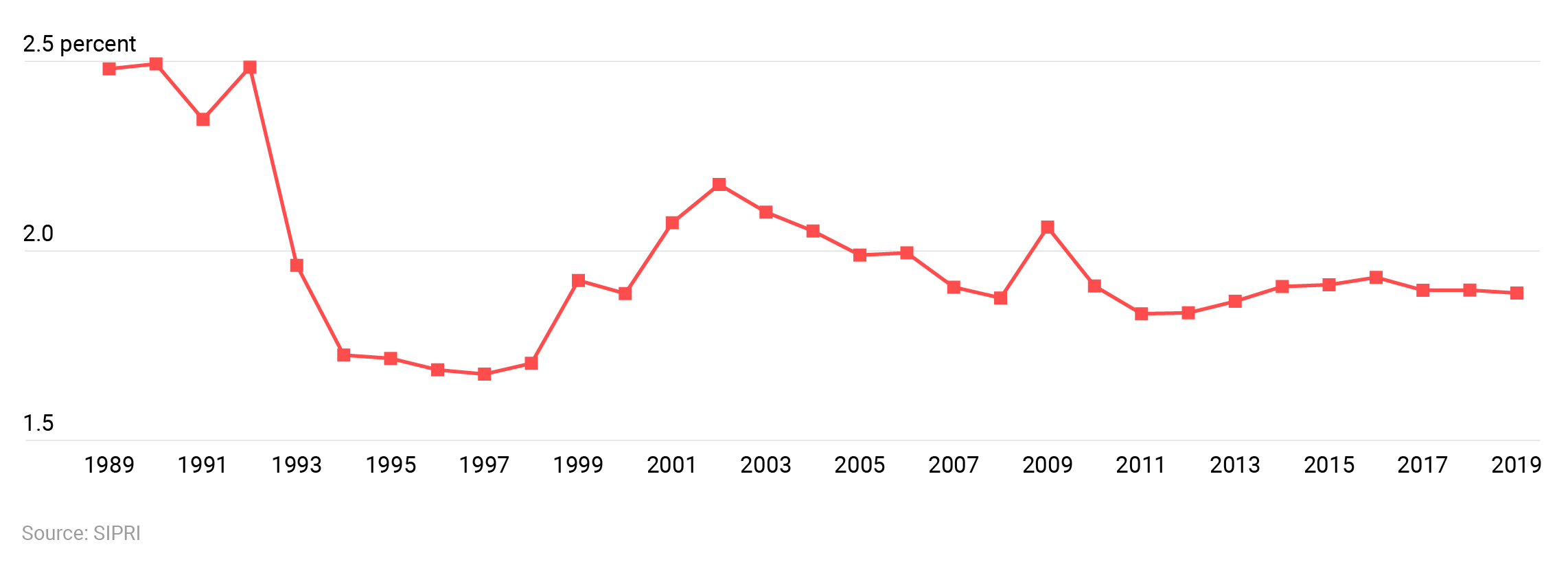

Though recently slowing, China’s economic growth since 1990 has reduced the wealth gap with the U.S. For four decades, China’s economy grew at a rapid pace, allowing it to shrink its wealth gap with the United States. From 2000 to 2018 alone, China’s GDP grew from $1.2 trillion to $13.6 trillion, a 1033% increase.2“GDP (current US$)—China,” World Bank, accessed July 3, 20120, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?locations=CN. Wealth creation enabled China to modernize and strengthen its military, especially its defensive capabilities. Chinese inflation-adjusted annual military spending increased from $43 billion to $253 billion over that same period, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (China’s official figures are significantly lower and are generally believed to be underestimates).3“SIPRI Military Expenditure Database,” Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, accessed July 3, 2019, https://www.sipri.org/databases/milex; “What Does China Really Spend on its Military?” China Power, December 28, 2015, updated May 22, 2020, https://chinapower.csis.org/military-spending/. This is a reflection of greater prosperity; however, Chinese military spending as a percent of GDP has actually declined over time and has consistently been about half of U.S. military spending levels.4David C. Kang, American Grand Strategy and East Asian Security in the Twenty-First Century (Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press, 2017).

Much of China’s military spending is invested in domestic security, such as intelligence and surveillance to quell dissent, and ground forces largely focused on internal security.5M. Taylor Fravel, Active Defense: China’s Military Strategy Since 1949 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2019). A substantial portion has also gone toward fortifying China’s borders or defending its near abroad—acquiring defensive weapons (like anti-air and anti-ship missiles) that render the waters of East Asia more dangerous to powerful adversaries such as the United States.6Eugene Gholz, Benjamin Friedman, and Enea Gjoza, “Defensive Defense: A Better Way to Protect U.S. Allies in Asia,” The Washington Quarterly 42, no. 4 (2019): 171–189, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/0163660X.2019.1693103. Relatively little of China’s spending goes to offensive capabilities—like aircraft carriers, amphibious vehicles, bomber aircraft, longer-range submarines—and other military means to project power far from its shores.”7Oriana Skylar Mastro, “China’s Military Modernization Program,” AEI, September 4, 2019, https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/Panel%20II%20Mastro_Written%20Testimony.pdf.

China’s military spending as a percent of GDP

As a percent of GDP, China’s military spending has remained steady over decades, averaging roughly half of DoD spending. The much larger U.S. economy means that difference is even more stark in dollars. In 2019, China spent $266 billion on its military compared to roughly $719 billion for the U.S.

China’s naval modernization has aimed to create a force that fights within the first island chain to prevail in a local war.8Anthony H. Cordesman, Ashley Hess, and Nicholas S. Yarosh, “Chinese Military Modernization and Force Development,” CSIS, September 30, 2013, 180, https://www.csis.org/analysis/chinese-military-modernization-and-force-development-0. Its fleet remains ill-equipped to sustain an amphibious assault against a capable foe and its investment in prestige items, such as aircraft carriers, has not come with sustained investments in the training, combat readiness, and operational support needed to sustainably project this capability.9“Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2019,” Office of the Secretary of Defense, 2019, https://media.defense.gov/2019/May/02/2002127082/-1/-1/1/2019_CHINA_MILITARY_POWER_REPORT.pdf; Charles Clover, “China: Projections of power,” Financial Times, April 8, 2015, https://www.ft.com/content/12424108-da0b-11e4-9b1c-00144feab7de.

Even China’s most cherished military goal—the conquest and reunification of Taiwan—has not received the kind of intensive investment in amphibious capability that one might expect. Although China has substantially heightened its ability to bombard Taiwan with missiles, the amphibious fleet it would need to invade Taiwan remains insufficient and vulnerable. Recent analysis shows that Taiwan retains the ability, even in the absence of U.S. military support, to resist to the point that its conquest is hardly a sure thing.10Eric Heginbotham et al., The U.S.-China Military Scorecard: Forces, Geography, and the Evolving Balance of Power, 1996–2017 (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2015); Michael Beckley, “The Emerging Military Balance in East Asia: How China’s Neighbors Can Check Chinese Naval Expansion,” International Security 42, no. 2 (Fall 2017): 78–119.

Constraints preventing Chinese hegemony in East Asia

China’s internal weaknesses

Although the long-term impact remains to be seen, the coronavirus pandemic may hit China hard, as with other major powers.11Barry Posen, “Do Pandemics Promote Peace?” Foreign Affairs, April 23, 2020, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/china/2020-04-23/do-pandemics-promote-peace. Some of China’s trading partners may be wary of retaining deep economic ties given the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) unpredictability and fears of future supply disruptions. Prime Minister Shinzo Abe of Japan cites China’s haphazard response to the coronavirus pandemic as a reason for Japanese companies to relocate supply chains from the Chinese mainland, and his government created a $3.2 billion subsidy fund to assist relocation.12Walter Sim, “Coronavirus: Japan PM Shinzo Abe Calls on Firms to Cut Supply Chain Reliance on China,” Straits Times, April 16, 2020, https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/east-asia/coronavirus-japan-pm-shinzo-abe-calls-on-firms-to-cut-supply-chain-reliance-on-china. Changes in consumer habits worldwide (greater saving, less spending) could harm both China’s export-led model and any attempts to transition to an economy driven by domestic consumption.13Katie Jones, “These charts show how COVID-19 has changed consumer spending around the world,” World Economic Forum, May 2, 2020, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/05/coronavirus-covid19-consumers-shopping-goods-economics-industry/; Kenneth Rapoza, “New Data Shows U.S. Companies Are Definitely Leaving China,” Forbes, April 7, 2020, https://www.forbes.com/sites/kenrapoza/2020/04/07/new-data-shows-us-companies-are-definitely-leaving-china/#61c4c7c540fe. This bodes poorly for Chinese growth, which under an effective recovery would likely be 2 to 3 percent this year, compared to the 5.5 percent projections pre-COVID-19.14Sarah Tong and Li Yao, “How Much Will the Chinese Economy Be Damaged by COVID-19?” Brink News, May 12, 2020, https://www.brinknews.com/how-much-is-the-chinese-economy-going-to-be-damaged-by-covid-19-coronavirus/.

Even before the coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan, the Chinese economy was losing steam. China’s rate of growth has declined in recent years, from a high of 14.2 percent in 2007 to 6.6 percent in 2018.15“GDP (current US$)—China.” China also suffers from structural vulnerabilities. These include large but poorly run state-owned enterprises, high corporate debt, and heavy reliance on foreign commodities—energy and minerals especially—which are vulnerable to supply disruptions at sea.16“What’s Really Behind China’s Falling GDP,” Wharton School, July 19, 2019, https://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/article/chinas-gdp-falling/.

China expends heavy resources containing domestic dissent (Hong Kong being the most recent example) and restive minority groups in its peripheral regions (Xinjiang and Tibet have both been subjected to draconian control measures). Chinese domestic security spending outpaced military spending by nearly 20 percent in 2017.17Josh Chin, “China Spends More on Domestic Security as Xi’s Powers Grow,” Wall Street Journal, March 6, 2018, https://www.wsj.com/articles/china-spends-more-on-domestic-security-as-xis-powers-grow-1520358522. These resources cannot be deployed toward more productive ventures or used on military capabilities more useful in projecting power. Failure to deliver the steady economic gains the public demands will likely increase Beijing’s costs to pacify domestic discontent, reducing foreign adventurism.

Regional powers and defensible geography

Unlike the U.S.—which has two oceans on its shores and weak, friendly neighbors—China is surrounded by numerous powers that naturally check its ambitions.

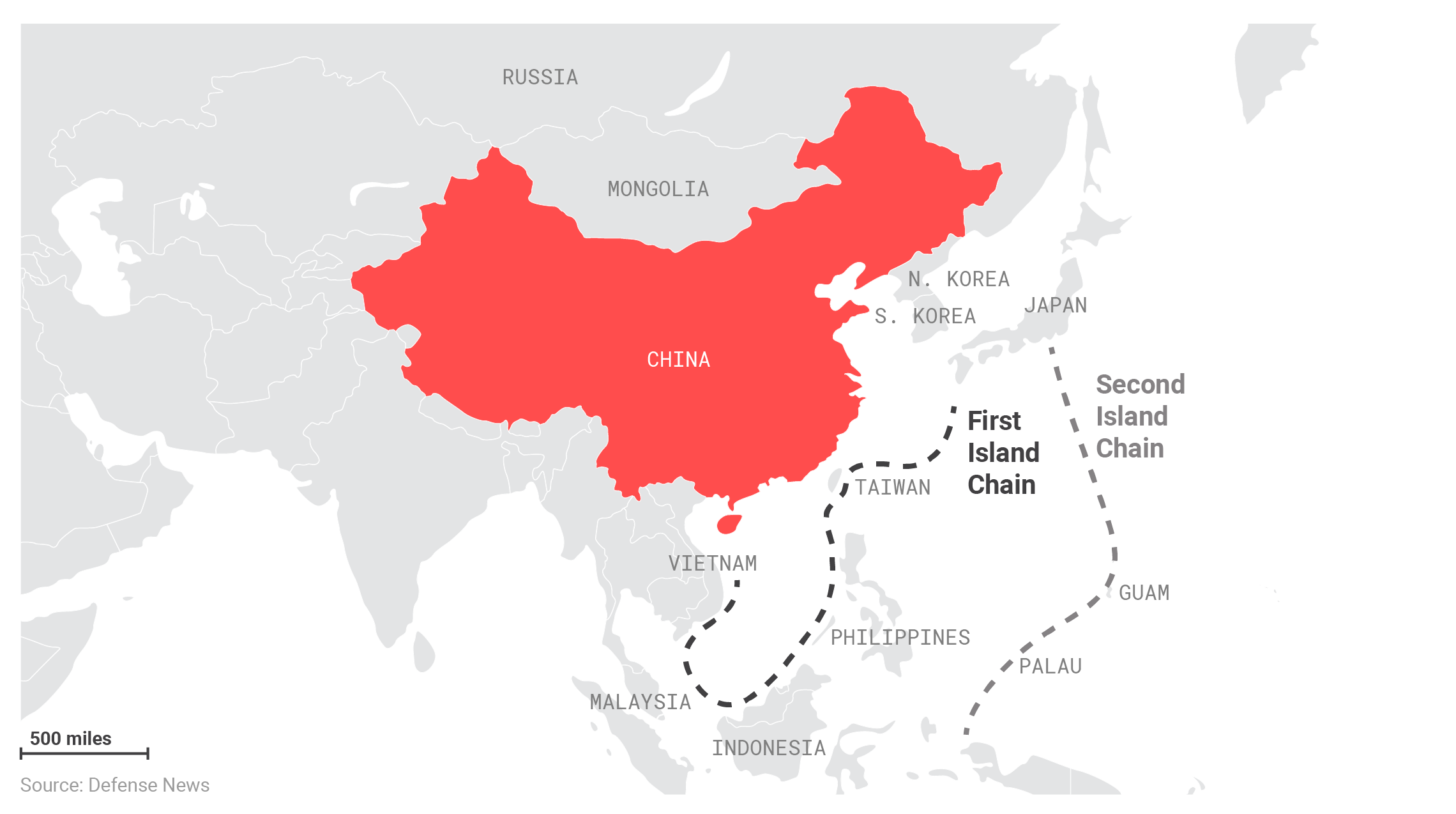

Geographical constraints on China’s navy

Asia’s first and second island chains, formed by the various islands of the East and South China seas, create natural bottlenecks that render the Chinese navy and commercial vessels vulnerable. U.S. allies or partners can fortify these islands to deny Chinese shipping and military vessels access to the waters of East Asia in the event of war.

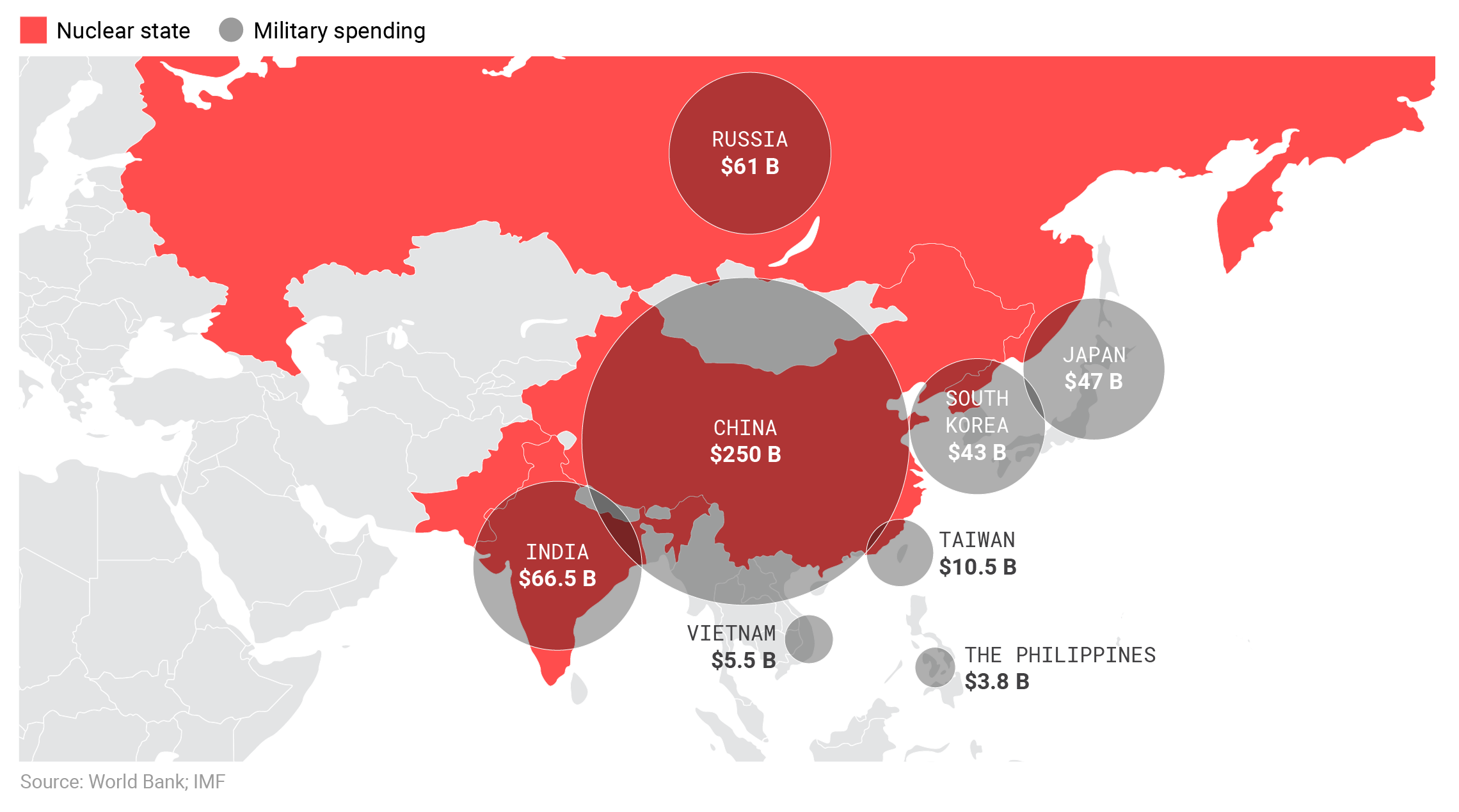

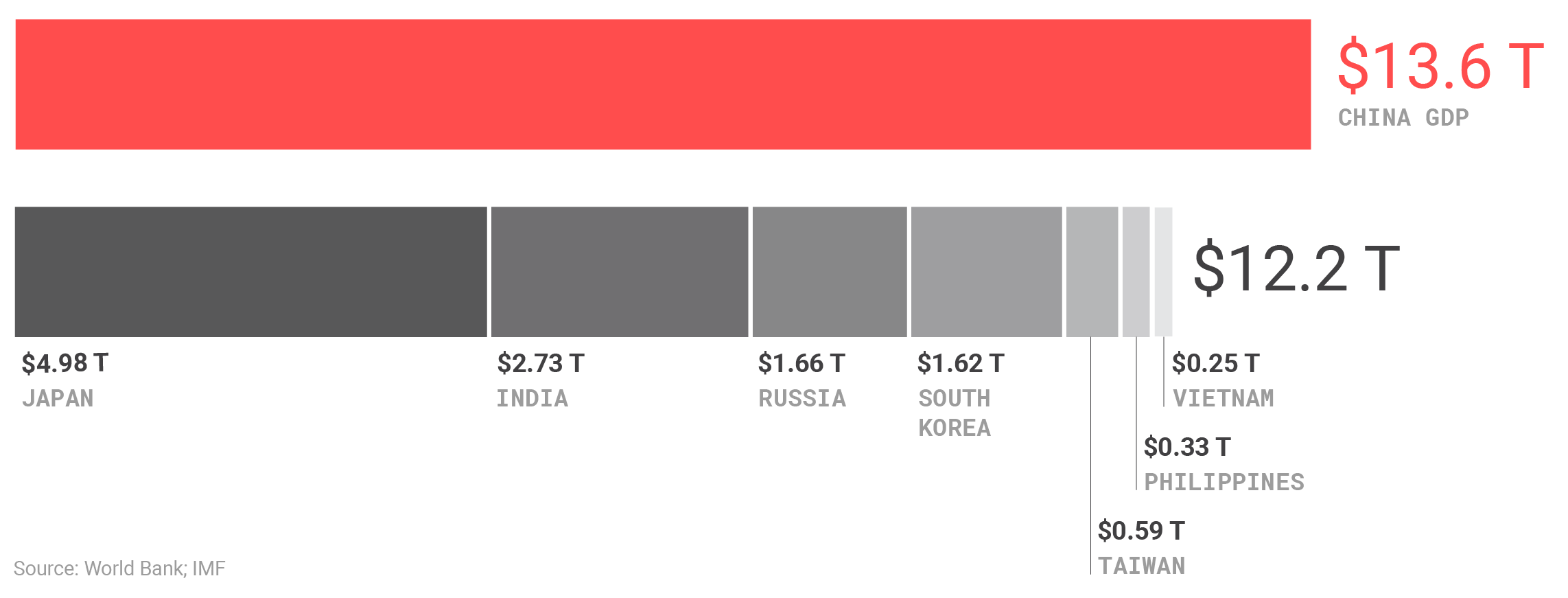

China shares a land borders with 14 countries and littoral seas with several more. These include great powers (Russia, India, and Japan), nuclear states (Russia, India, North Korea, and Pakistan), and middle powers with formidable defenses (South Korea, Taiwan, and Vietnam). China’s recent border conflict with India is a reminder that its frontiers are more military burdens it bears than invitations to expand.

Conquest and occupation are difficult and expensive, even in relatively weak states, as the U.S. learned to its harm in Iraq and continues to suffer in Afghanistan.18Barry R. Posen, Restraint: A New Foundation for U.S. Grand Strategy, (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2015). The proliferation of small arms and improvised explosives, combined with nationalist sentiments that motivate locals to resist foreign invaders, allow even weak nations to bleed far more powerful foes. China seems to recognize this and has shown no real interest in seizing territory other than Taiwan and the resource-rich waters off its shores (in just the South China Sea, it should be pointed out, no fewer than five nations challenge China for sovereignty of key islands or areas).19“Explained: South China Sea dispute,” South China Morning Post, February 16, 2019, https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/article/2186449/explained-south-china-sea-dispute. In China’s three wars since 1949, Chinese forces captured territory in India, North Korea, and Vietnam, yet essentially abandoned those gains once the conflict ended.20Eric S. Margolis, War at the Top of the World: The Struggle for Afghanistan, Kashmir and Tibet (New York: Routledge, 2001), 288.

Capable rivals prevent potential Chinese expansion

Geography limits opportunities for China to expand: jungles to the south, mountains to the west, and seas to the east. It is also surrounded by numerous capable, well-armed nations (in some cases with nuclear weapons) whose forcible subjugation would present a serious military challenge.

China also sits amid geography—mountains to its west, jungles to its south, and a large body of water to its east—that makes conquering its neighbors challenging.21Robert S. Ross, “The Geography of the Peace: East Asia in the Twenty-First Century,” International Security 23, no. 4 (Spring 1999), 81–118, https://www.jstor.org/stable/2539295?seq=1. This is particularly the case for islands such as the Philippines, Taiwan, Indonesia, and Japan. China currently operates a mostly brown-, rather than blue-, water navy, meaning it is designed to operate near its shores, not project power. Maritime invasions across great distances and against well-fortified coastlines require enormous naval assets (which China does not presently have) and tend to be exceptionally costly—and they tend to fail.

At present, China’s neighbors, aside from Taiwan, also appear to perceive limited threat to their sovereignty. Like China, their military spending as a percentage of GDP has also remained relatively steady or in some cases declined.22“Military expenditure (% of GDP) – Philippines, Vietnam, Japan, Indonesia, Malaysia, Korea, Rep.,” World Bank, accessed May 25, 2020, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/MS.MIL.XPND.GD.ZS?locations=PH-VN-JP-ID-MY-KR. Should China’s threat grow, many of China’s neighbors are well-positioned to put up stiff resistance, especially if the U.S. military transitions to a supporting role, rather than a first responder.23Denny Roy, “China Won’t Achieve Regional Hegemony,” The Washington Quarterly, 43, no. 1 (March 19, 2020): 101–117, https://cpb-us-e1.wpmucdn.com/blogs.gwu.edu/dist/1/2181/files/2020/03/Roy_43-1.pdf. China’s access to the world’s oceans is limited by Asia’s first and second island chains, which provide a staging ground for hostile forces that could target Chinese naval vessels or shipping in war.24Yoji Koda, “China’s Blue Water Navy Strategy and its Implications,” Center of New American Security, March 20, 2017, https://www.cnas.org/publications/reports/chinas-blue-water-navy-strategy-and-its-implications. This becomes an even more formidable barrier if U.S. allies bolster the defenses of these islands by improving their A2/AD technologies.25Gholz, Friedman, and Gjoza, “Defensive Defense.”

Nuclear weapons deter China and make war less likely by raising the stakes

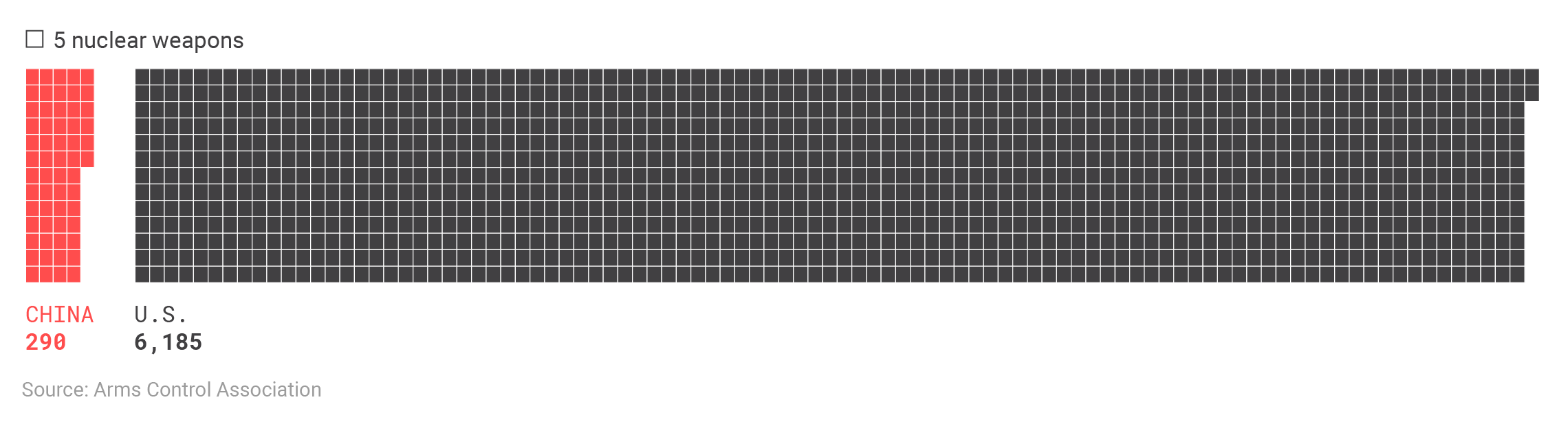

The U.S. and China deter each other through their nuclear arsenals. The U.S. is the far superior power, but China’s minimum deterrence posture—which maintains only enough nuclear weapons to discourage an attack—is still sufficient to limit the extent to which the U.S. can coerce it.26M. Taylor Fravel and Evan S. Medeiros, “China’s Search for Assured Retaliation,” International Security 35, no. 2 (Fall 2010): 48–87, https://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/ISEC_a_00016. The prospect of a nuclear exchange is likely to make Washington and Beijing wary of even a limited direct confrontation, which could spiral out of control—this reality reduces the risks of war.

China’s nuclear doctrine calls for a “no first use” policy: Beijing says it will not launch nuclear attacks on other nations first, but it maintains a nuclear capability to deter attacks. The small size of China’s arsenal—roughly 300 nuclear warheads compared to more than 6,000 total U.S. warheads—and the fact China has not significantly expanded it over time suggest Beijing is not merely paying lip service to this doctrine.27“Nuclear Weapons: Who Has What at a Glance,” Arms Control Association, July 2019, https://www.armscontrol.org/factsheets/Nuclearweaponswhohaswhat; Fravel and Medeiros, “China’s Search for Assured Retaliation.”

Nuclear arsenals of the U.S. and China

China’s small nuclear arsenal remains primarily defensive. Even if China implements an anticipated doubling of its nuclear stockpile over the next decade, the U.S. retains an overwhelming advantage.

What to watch: Benchmarks that signal a Chinese bid for domination

If China were to grow powerful enough to entirely dominate East Asia, it could theoretically marshal the resources it acquires to grow further and potentially dominate the broader Eurasian landmass.28Hal Brands, “What Does China Really Want? To Dominate the World,” Bloomberg, May 20, 2020, https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2020-05-20/xi-jinping-makes-clear-that-china-s-goal-is-to-dominate-the-world. Such dominance would allow China to project power globally, even into the Western Hemisphere. The U.S. became a superpower in much the same way. Were China sufficiently to marshal the resources of the Eurasian landmass while the U.S. stood passively by, it could eventually possess the means to threaten the U.S. homeland directly or deny the U.S. commercial access to the world’s economic centers.

One of the driving reasons the U.S. fought World War II and formed NATO was to deny the Soviet Union the ability to dominate and organize Europe during the Cold War. Such an outcome for China in the near or mid-term is not likely, however, because China is surrounded by powerful states, several of them nuclear armed—and the continued global power of America’s conventional military and nuclear arsenal will constrain it.

Despite the flood of articles in Western media about China’s growing ambitions abroad, its foreign policy still pursues fairly modest aims. A shift to an expansionist foreign policy would be preceded by events that would allow the U.S. ample time—measured in 7- to 10-year timeframes—to react and shift policy should U.S. security or prosperity be directly threatened.

Military power projection

To dominate the region, China would need to invest much more heavily in power projection capabilities: additional aircraft carriers—it currently has two, one of which is a refitted Soviet-era carrier—scores of additional large surface ships, bombers, and transport ships. This would require both an increase in Chinese topline military spending from its current level of roughly $260 billion and a substantial reallocation of resources away from the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) and toward the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN).

Bordering states augment their defenses

A Chinese move toward an aggressive, expansionist foreign policy would change the threat perception of neighboring states. They would respond by taking steps to defend themselves more effectively, including increasing military spending, shifting military investment toward platforms designed to counter China (anti-air and anti-ship), and becoming more vocal about the Chinese threat in international forums. States could also band together to balance Chinese power more effectively, seek more outside help from the U.S. or others, or even politically capitulate in the hopes of currying favor with China. It is important to note that the current forward U.S. military presence in East Asia has likely encouraged these states to forgo some improvements in their defenses they otherwise would have made.

GDP of China compared to other regional powers and key neighbors

China is the preeminent economic power in East Asia, but its neighbors collectively possess the wealth to balance China by augmenting their military capabilities or creating new alliances.

Reintegration of Taiwan

The U.S. recognizes Taiwan as part of China under its longstanding “One China” policy, although in practice, U.S. defense policies ensure its independence through weapons sales and “strategic ambiguity.”29Pan Zhongqi, “U.S. Taiwan Policy of Strategic Ambiguity: A Dilemma of Deterrence,” Journal of Contemporary China 12, no. 35 (2003): 287–407, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/1067056022000054678?journalCode=cjcc20. China has staked a claim to Taiwan since the island broke off from the CCP-controlled mainland in 1949. Returning Taiwan to mainland control remains China’s top foreign policy priority.

For China, resolving Taiwan’s status would probably be a necessary first step to a campaign for regional dominance. This is more for reasons of internal politics than its strategic utility. Conquest of Taiwan would be a warning that further aggression might follow but hardly guarantees it.

Of course, a Chinese attempt to conquer Taiwan might fail. Even if successful, it would not necessarily be a prelude to further aggression. Taiwan is a unique issue. And going beyond Taiwan would require Beijing to undertake a massive, years long expansion of their air and naval fleets to build sufficient power projection capabilities that presently do not exist.

A campaign of regional aggression—and its discontents

A Chinese shift toward attempting military hegemony would be impossible to miss and allow the U.S. time to assess the nature of the potential threat. Yet even if China attempted to conquer neighbors and succeeded, its “victory” would have disastrous consequences—likely enmeshing it in prolonged, costly counterinsurgencies or military stalemates. The U.S. experienced this phenomenon in the Middle East. Russia is experiencing it in Ukraine, and similar troubles helped destroy the Soviet Union. China would be no different, as its 1979 incursion into Vietnam demonstrated.30On overexpansion, see Jack Snyder, Myths of Domestic Politics and International Ambition (Ithaca NY: Cornell University Press, 1993).

Dominating a landmass as geographically large and diverse as Eurasia is a nearly impossible task under current circumstances: it would require China to bring many wealthy, advanced, dispersed, and in some cases nuclear-armed states under its sway. A campaign of aggression would not play to China’s strengths, since projecting power is costly, and China faces pressure to continue improving living standards at home. The U.S. has struggled for nearly 20 years to manage a small portion of the Middle East, a region that accounts for 4 percent of global GDP, without success.31“GDP (current US$)—Middle East & North Africa,” World Bank, accessed July 3, 2012, World Bank, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?locations=ZQ-1W. Chinese territorial adventurism would likely be a long-term disaster for China.

Where China excels is in its defensive capabilities—its A2/AD military investments have made it costly for the U.S. to project military power near China’s shores. But A2/AD is not a solely Chinese advantage, but a “defender’s” advantage, especially prevalent where advanced economies defend coasts. Technological advances make it cheaper to defend against invading forces, a reality that is exceedingly costly for the U.S. to attempt to overcome. This same reality makes it easier for China’s neighbors to fortify themselves without matching Chinese military spending.

Granting China “elbow room” costs nothing and reduces the risk of conflict

While Chinese dominance of East Asia is unlikely, China is a large nation of 1.3 billion people with considerable wealth. It will seek, and inevitably exert, influence in its own periphery. This “elbow room”—the ability to operate with greater flexibility and lower fear of peer-rival interference in its near abroad—is something great powers tend to carve out for themselves.

Acknowledging this reality and permitting China some measure of security from a foreign military presence in its near abroad is advantageous for the U.S.: It allows Beijing to feel safe enough to limit arms racing and other risky behavior. This does not mean letting China run roughshod over allies, but rather shifting the U.S. military posture away from attempting to suppress China and instead encouraging its Asian neighbors to balance China’s power.

The U.S. Navy’s frequent forays in disputed waters near China—combined with the capability to strike targets on the Chinese mainland—has antagonized Beijing and depressed U.S.-Asian allied investments in defensive capabilities to deter China. It has also sparked security dilemma dynamics, where each side’s defensive measures tend to be perceived as offensive and alarm the other. This circumstance encourages China to fortify its defensive capabilities further and the U.S. to respond by deploying additional and expensive power-projection capabilities to overcome those improvements, and so on. In the event of war or crisis, Beijing might fear that a U.S. first blow will cripple its defenses or seek to topple the CCP, creating dangerous incentives to attack first.32Caitlin Talmadge, “Would China Go Nuclear? Assessing the Risk of Chinese Nuclear Escalation in a Conventional War with the United States,” International Security 41, no. 4 (Spring 2017): 50–92.

Recommendations

U.S. goals are defensive and should be advanced with a defensive strategy

The U.S. is seeking to prevent potential Chinese aggression or expansionism and safeguard the territorial integrity of East Asian allies, goals that are primarily defensive in nature. Such goals are best advanced with a defensive strategy and deterrence.

A security model in which the U.S. takes primary responsibility for ensuring the territorial integrity of allies is inefficient and risky. It is far more costly for the U.S. to defend distant allies than for them to take responsibility for their own security. This is compounded by the prospect of facing a modern, near-peer adversary enjoying the advantage of fighting in its backyard.

America’s Asian allies, the key targets of possible Chinese aggression, are wealthy and technologically advanced and should take responsibility for deterring that aggression and defending their own borders. Shifting the burden to them was always sensible given the economic realities of China’s rapid growth, but with the U.S. economy debt-laden and facing contraction following economic disruption from combatting the coronavirus, an accelerated transition to a new security model is more urgent.

Allied security can be achieved by providing allies with the weapons and technology to deter potential Chinese expansionism.33Gholz, Friedman, and Gjoza, “Defensive Defense.” Pushing allies to invest more in A2/AD weapons and capabilities of their own, which allow defenders to effectively counter a stronger attacker, is a far more efficient security solution than the warplanes and surface ships U.S. allies are currently purchasing. Unlike mirroring U.S. capabilities, A2/AD systems are viable for limited defense budgets.

U.S. forces should serve as a balancer of last resort in war, rather than the primary combatant. This makes escalation with China less likely and the U.S. military burden more manageable. The U.S. should therefore prioritize avoiding military confrontation while closely monitoring China to ensure no direct security threat to the U.S. arises.

By avoiding short-term exhaustion, needlessly seeking to contain an inflated military threat, the U.S. can shed peripheral burdens and focus on its recovery, thus strengthening our ability to defend our interests should a clash with China become unavoidable later.

Distinguish between economic competition and military threats

A balanced China policy that cooperates with China where interests align, competes where they conflict, and recognizes where they don’t intersect is essential.

For the United States, great-power competition with China in the military realm should be limited. This avoids undesirable and potentially uncontrollable escalation that would be detrimental to U.S. security and prosperity. Economic competition on the other hand is not, by itself, something to be feared, nor must it lead to a potential future military clash with the United States. Economic competition among nations can be a net positive, as a comparison between the Chinese and American ways of doing business can illuminate superior products, services, and customer experiences.

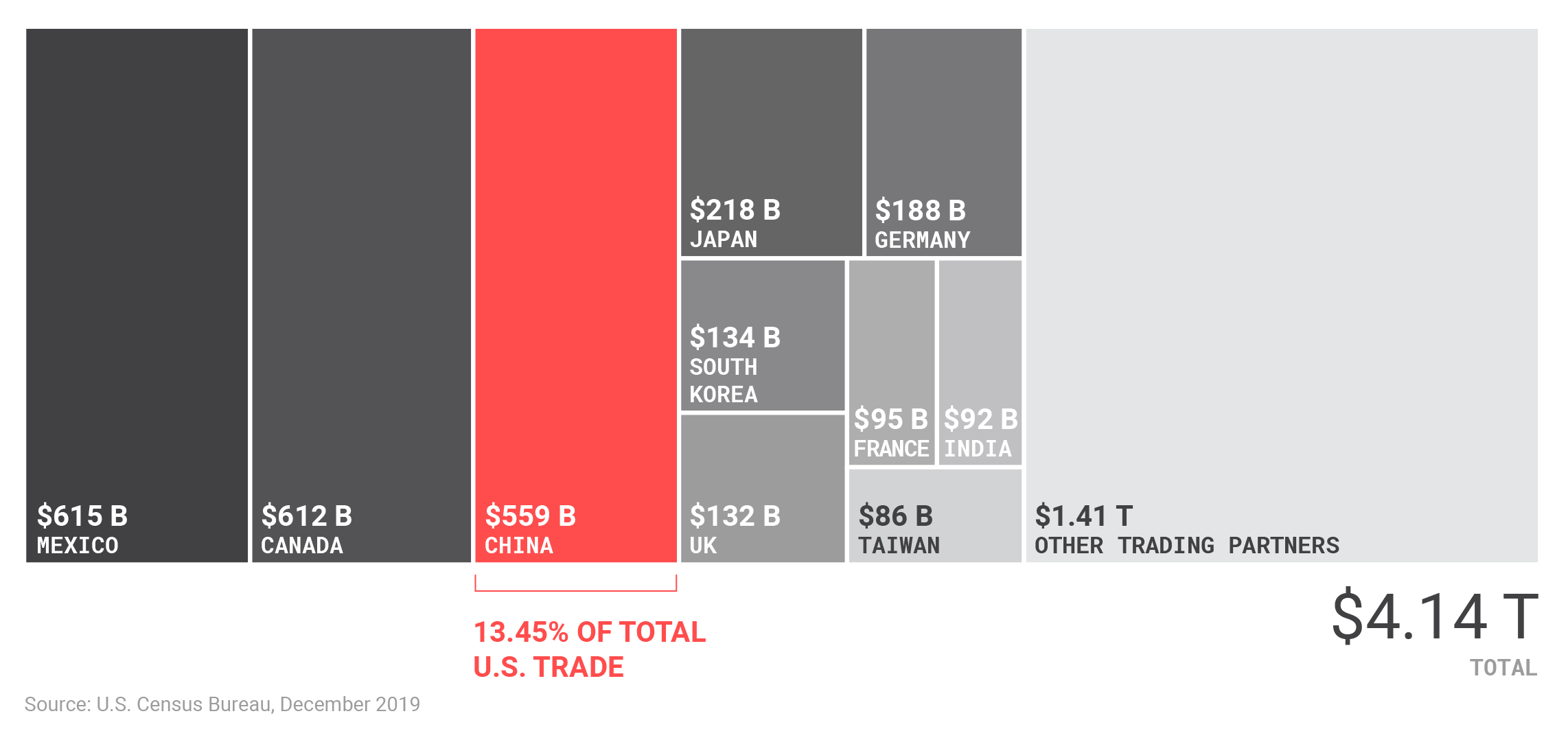

Total exchange between the U.S. and trading partners

China remains an important trade partner for the U.S., although one of several. Decoupling from China would not correct the U.S. trade deficit but would raise costs on many U.S. consumers and businesses.

U.S. prosperity relies on continued commercial relationships with China, even if the specifics of the trade relationship change significantly. China is one of the biggest markets for many U.S. companies and is a major supplier of inputs for domestic producers. Forcibly decoupling the U.S. and Chinese economies, unwinding complex and sophisticated supply chains, would be destructive for many industries and costly to U.S. consumers and producers alike.34Daniel Smith, “Moving Supply Chains Out of China Isn’t So Easy,” Sourcing Journal, January 29, 2019, https://sourcingjournal.com/topics/thought-leadership/moving-supply-chains-out-of-china-136116/.

For rare industries with major security value, like military components or some pharmaceuticals, the U.S. can explore the feasibility of reshoring. But even in those cases, nuance exists. U.S. pharmaceuticals often rely on active ingredients from China, but most of the value-add occurs domestically.35Laurie McGinley and Carolyn Y. Johnson, “Coronavirus raises fears of U.S. drug supply disruptions,” Washington Post, February 26, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/2020/02/26/coronavirus-raises-fears-us-drug-supply-disruptions/.

The U.S. should avoid declaring every industry strategic as a cover for protectionism. Production has moved to China primarily because it is less costly than producing domestically. Forcible onshoring would drive up costs for Americans.

U.S. security commitments in Asia and trade dynamics do make some military and economic competition (not conflict) between the world’s two greatest powers inevitable. But geography, starting with the Pacific Ocean, and the positive sum fundamentals of trade mitigate the dangers of competition. The U.S. should strive to avoid the worst consequences of economic rivalry and channel the contest in useful ways—toward domestic improvements conducive to our nation’s long-term strength.

Analysis of China’s rise too often conflates economic issues with military threats. China’s bullying of companies’ speech (like the NBA), its granting dubious loans to developing nations through its Belt and Road Initiative, or its state-run companies getting business abroad are examples of issues that result from China’s wealth and might merit some U.S. concern and response—but they are not U.S. security threats.

The U.S. should maintain a balance between protecting its innovation hubs (universities and private sector firms) from intellectual property theft, while also allowing foreign researchers and scientists to do research work that benefits the U.S. economy. Drawing talented students and scientists to the U.S. is a major benefit provided by the U.S. higher education system that should be protected.

The U.S. should acknowledge there are limits to what it can ask of allies

U.S. concerns about China’s economic power had led to policies meant to conscript European allies into U.S. efforts to blunt China’s successes both commercially and in international institutions. This has resulted in some embarrassing defeats, including the mass defection of European states to the China-led Asian International Investment Bank (AIIB) over U.S. objections, and the difficulty convincing key allies to ban Huawei from their future telecommunications development.

Allies face their own incentives in dealing with China and the U.S., as well as domestic pressure from their publics to secure certain benefits (new technology, trade deals, and foreign investment). Europe at times competes with the U.S. economically. Sometimes those interests dictate cooperating with China despite massive defense subsidies and pleas from the U.S.36Sasha Toperich and Aylin Ünver Noi, Turkey and Transatlantic Relations, (Washington, DC: Center for Transatlantic Relations, Johns Hopkins University, 2017), https://archive.transatlanticrelations.org/publication/turkey-transatlantic-relations/. Seeking to preclude European involvement in other Chinese projects when their economic interests dictate otherwise is unlikely to succeed.

In the case of Europe specifically, the U.S. should acknowledge its European allies are not united on China and will only cooperate with U.S. policy up to a point. While European nations benefit from U.S. security guarantees and economic trade, many of them also stand to benefit economically from China’s rise. They are therefore unlikely to choose one over the other entirely. Depending on the nation and issue area, interests among European nations can vary widely. The U.S. should engage diplomatically with those states whose interests align with its own and engage diplomatically to re-align interests where possible when they diverge.

The U.S. should avoid driving Russia and China together

Over the past two decades, the U.S. has attempted to simultaneously contain Russia and China, denying both elbow room. This policy has driven Moscow and Beijing—historic rivals—closer together. The U.S. attempted to contain Russia by expanding NATO and deploying U.S. troops to Eastern Europe. In China’s case, the “pivot to Asia” and U.S. Navy freedom of navigation operations near China’s coast are designed to mark the limits of China’s regional sway. The 2017 National Security Strategy calls for doubling down on this approach, making “great power competition” with both Russia and China a priority for the U.S.37“National Security Strategy of the United States of America,” The White House, December 2017, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/NSS-Final-12-18-2017-0905.pdf. This is a mistake that will do more to encourage Russia and China to balance against the U.S.

Both Russia and China feel threatened by U.S. military power and alliance relationships near their borders and are on the receiving end of U.S economic pressure—Russia in the form of sanctions and China through the trade war and decoupling proposals. This has led them to enhance economic and military cooperation—signing trade and energy agreements and carrying out their largest joint military exercise ever in 2018.38Russia invited China to participate in its largest military exercise in four decades, featuring an estimated 300,000 Russian troops. It was the first time China had has participated in Russia’s annual strategic exercises. Franz-Stefan Gady, “Russian, Chinese Troops Kick off Russia’s Largest Military Exercise Since 1981,” The Diplomat, September 12, 2018, https://thediplomat.com/2018/09/russian-chinese-troops-kick-off-russias-largest-military-exercise-since-1981/. Examples of economic cooperation between China and Russia include a $270 billion oil deal in 2013, a $400 billion gas deal signed in 2014, and a $55 billion pipeline connecting the two nations. Courtney Weaver and Neil Buckley, “Russia and China agree $270bn oil deal,” Financial Times, June 21, 2013, https://www.ft.com/content/ebc10e76-da55-11e2-a237-00144feab7de; Alexei Anishchuk, “As Putin looks east, China and Russia sign $400-billion gas deal,” Reuters, May 21, 2014, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-russia-gas/as-putin-looks-east-china-and-russia-sign-400-billion-gas-deal-idUSBREA4K07K20140521; Georgi Kantchev, “China and Russia Are Partners—and Now Have a $55 Billion Pipeline to Prove It,” Wall Street Journal, December 1, 2019, https://www.wsj.com/articles/china-and-russia-are-partnersand-now-have-a-55-billion-pipeline-to-prove-it-11575225030.

Sino-Russian cooperation is unlikely to take the form of a formal alliance, but that prospect is sufficiently alarming that the U.S. should studiously avoid it. Russia and China have a history of fraught relations marked by violent border disputes. As China grows stronger, Russia is increasingly becoming the subordinate partner—a point of frustration for Moscow. Yet Russia will continue to lean into its larger neighbor as long as it believes the U.S. is the bigger and more immediate threat.

U.S. policy that avoids driving China and Russia together could mean reducing U.S. pressure on Russia, the weaker competitor, by easing sanctions, halting NATO expansion, and ending military aid to Ukraine. By relaxing the U.S. military posture in Asia—which an allied A2/AD security model would achieve—the U.S. could also avoid incentivizing China from bringing Russia closer into its orbit.

U.S.-China hostility is not inevitable

Continued U.S. preeminence in world affairs depends on wise policy and the conservation of U.S. power, rather than expending it in an excessive and ultimately counterproductive competition with China. By needlessly confronting China everywhere, the U.S. will exhaust itself—diverting enormous sums attempting to contain Beijing in its own backyard, damaging goodwill with allies (who have commercial and political incentives to maintain ties to China in addition to the U.S.), and raising the risk of a direct conflict with a nuclear-armed state. This is neither effective nor necessary.

The U.S. can maintain its economic primacy by fostering domestic innovation through regulatory reform, investment in research and development, and better education and infrastructure at home. China’s military power can largely be contained through U.S. allies—armed with U.S.-supplied A2/AD defenses—and other regional states which fear an expansionist China and will resist its encroachment on their territory. Through diplomacy, the U.S. can also retain its preeminent position in international institutions and form coalitions to challenge detrimental Chinese policies as necessary.

As the two largest economies in the world, the U.S. and China are both essential to the international system and should find a way to coexist peacefully.

Endnotes

- 1Andrea Willige, “The World’s Top Economy: The U.S. vs China in Five Charts,” World Economic Forum, December 5, 2016, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/12/the-world-s-top-economy-the-us-vs-china-in-five-charts/.

- 2“GDP (current US$)—China,” World Bank, accessed July 3, 20120, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?locations=CN.

- 3“SIPRI Military Expenditure Database,” Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, accessed July 3, 2019, https://www.sipri.org/databases/milex; “What Does China Really Spend on its Military?” China Power, December 28, 2015, updated May 22, 2020, https://chinapower.csis.org/military-spending/.

- 4David C. Kang, American Grand Strategy and East Asian Security in the Twenty-First Century (Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press, 2017).

- 5M. Taylor Fravel, Active Defense: China’s Military Strategy Since 1949 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2019).

- 6Eugene Gholz, Benjamin Friedman, and Enea Gjoza, “Defensive Defense: A Better Way to Protect U.S. Allies in Asia,” The Washington Quarterly 42, no. 4 (2019): 171–189, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/0163660X.2019.1693103.

- 7Oriana Skylar Mastro, “China’s Military Modernization Program,” AEI, September 4, 2019, https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/Panel%20II%20Mastro_Written%20Testimony.pdf.

- 8Anthony H. Cordesman, Ashley Hess, and Nicholas S. Yarosh, “Chinese Military Modernization and Force Development,” CSIS, September 30, 2013, 180, https://www.csis.org/analysis/chinese-military-modernization-and-force-development-0.

- 9“Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2019,” Office of the Secretary of Defense, 2019, https://media.defense.gov/2019/May/02/2002127082/-1/-1/1/2019_CHINA_MILITARY_POWER_REPORT.pdf; Charles Clover, “China: Projections of power,” Financial Times, April 8, 2015, https://www.ft.com/content/12424108-da0b-11e4-9b1c-00144feab7de.

- 10Eric Heginbotham et al., The U.S.-China Military Scorecard: Forces, Geography, and the Evolving Balance of Power, 1996–2017 (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2015); Michael Beckley, “The Emerging Military Balance in East Asia: How China’s Neighbors Can Check Chinese Naval Expansion,” International Security 42, no. 2 (Fall 2017): 78–119.

- 11Barry Posen, “Do Pandemics Promote Peace?” Foreign Affairs, April 23, 2020, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/china/2020-04-23/do-pandemics-promote-peace.

- 12Walter Sim, “Coronavirus: Japan PM Shinzo Abe Calls on Firms to Cut Supply Chain Reliance on China,” Straits Times, April 16, 2020, https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/east-asia/coronavirus-japan-pm-shinzo-abe-calls-on-firms-to-cut-supply-chain-reliance-on-china.

- 13Katie Jones, “These charts show how COVID-19 has changed consumer spending around the world,” World Economic Forum, May 2, 2020, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/05/coronavirus-covid19-consumers-shopping-goods-economics-industry/; Kenneth Rapoza, “New Data Shows U.S. Companies Are Definitely Leaving China,” Forbes, April 7, 2020, https://www.forbes.com/sites/kenrapoza/2020/04/07/new-data-shows-us-companies-are-definitely-leaving-china/#61c4c7c540fe.

- 14Sarah Tong and Li Yao, “How Much Will the Chinese Economy Be Damaged by COVID-19?” Brink News, May 12, 2020, https://www.brinknews.com/how-much-is-the-chinese-economy-going-to-be-damaged-by-covid-19-coronavirus/.

- 15“GDP (current US$)—China.”

- 16“What’s Really Behind China’s Falling GDP,” Wharton School, July 19, 2019, https://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/article/chinas-gdp-falling/.

- 17Josh Chin, “China Spends More on Domestic Security as Xi’s Powers Grow,” Wall Street Journal, March 6, 2018, https://www.wsj.com/articles/china-spends-more-on-domestic-security-as-xis-powers-grow-1520358522.

- 18Barry R. Posen, Restraint: A New Foundation for U.S. Grand Strategy, (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2015).

- 19“Explained: South China Sea dispute,” South China Morning Post, February 16, 2019, https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/article/2186449/explained-south-china-sea-dispute.

- 20Eric S. Margolis, War at the Top of the World: The Struggle for Afghanistan, Kashmir and Tibet (New York: Routledge, 2001), 288.

- 21Robert S. Ross, “The Geography of the Peace: East Asia in the Twenty-First Century,” International Security 23, no. 4 (Spring 1999), 81–118, https://www.jstor.org/stable/2539295?seq=1.

- 22“Military expenditure (% of GDP) – Philippines, Vietnam, Japan, Indonesia, Malaysia, Korea, Rep.,” World Bank, accessed May 25, 2020, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/MS.MIL.XPND.GD.ZS?locations=PH-VN-JP-ID-MY-KR.

- 23Denny Roy, “China Won’t Achieve Regional Hegemony,” The Washington Quarterly, 43, no. 1 (March 19, 2020): 101–117, https://cpb-us-e1.wpmucdn.com/blogs.gwu.edu/dist/1/2181/files/2020/03/Roy_43-1.pdf.

- 24Yoji Koda, “China’s Blue Water Navy Strategy and its Implications,” Center of New American Security, March 20, 2017, https://www.cnas.org/publications/reports/chinas-blue-water-navy-strategy-and-its-implications.

- 25Gholz, Friedman, and Gjoza, “Defensive Defense.”

- 26M. Taylor Fravel and Evan S. Medeiros, “China’s Search for Assured Retaliation,” International Security 35, no. 2 (Fall 2010): 48–87, https://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/ISEC_a_00016.

- 27“Nuclear Weapons: Who Has What at a Glance,” Arms Control Association, July 2019, https://www.armscontrol.org/factsheets/Nuclearweaponswhohaswhat; Fravel and Medeiros, “China’s Search for Assured Retaliation.”

- 28Hal Brands, “What Does China Really Want? To Dominate the World,” Bloomberg, May 20, 2020, https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2020-05-20/xi-jinping-makes-clear-that-china-s-goal-is-to-dominate-the-world.

- 29Pan Zhongqi, “U.S. Taiwan Policy of Strategic Ambiguity: A Dilemma of Deterrence,” Journal of Contemporary China 12, no. 35 (2003): 287–407, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/1067056022000054678?journalCode=cjcc20.

- 30On overexpansion, see Jack Snyder, Myths of Domestic Politics and International Ambition (Ithaca NY: Cornell University Press, 1993).

- 31“GDP (current US$)—Middle East & North Africa,” World Bank, accessed July 3, 2012, World Bank, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?locations=ZQ-1W.

- 32Caitlin Talmadge, “Would China Go Nuclear? Assessing the Risk of Chinese Nuclear Escalation in a Conventional War with the United States,” International Security 41, no. 4 (Spring 2017): 50–92.

- 33Gholz, Friedman, and Gjoza, “Defensive Defense.”

- 34Daniel Smith, “Moving Supply Chains Out of China Isn’t So Easy,” Sourcing Journal, January 29, 2019, https://sourcingjournal.com/topics/thought-leadership/moving-supply-chains-out-of-china-136116/.

- 35Laurie McGinley and Carolyn Y. Johnson, “Coronavirus raises fears of U.S. drug supply disruptions,” Washington Post, February 26, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/2020/02/26/coronavirus-raises-fears-us-drug-supply-disruptions/.

- 36Sasha Toperich and Aylin Ünver Noi, Turkey and Transatlantic Relations, (Washington, DC: Center for Transatlantic Relations, Johns Hopkins University, 2017), https://archive.transatlanticrelations.org/publication/turkey-transatlantic-relations/.

- 37“National Security Strategy of the United States of America,” The White House, December 2017, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/NSS-Final-12-18-2017-0905.pdf.

- 38Russia invited China to participate in its largest military exercise in four decades, featuring an estimated 300,000 Russian troops. It was the first time China had has participated in Russia’s annual strategic exercises. Franz-Stefan Gady, “Russian, Chinese Troops Kick off Russia’s Largest Military Exercise Since 1981,” The Diplomat, September 12, 2018, https://thediplomat.com/2018/09/russian-chinese-troops-kick-off-russias-largest-military-exercise-since-1981/. Examples of economic cooperation between China and Russia include a $270 billion oil deal in 2013, a $400 billion gas deal signed in 2014, and a $55 billion pipeline connecting the two nations. Courtney Weaver and Neil Buckley, “Russia and China agree $270bn oil deal,” Financial Times, June 21, 2013, https://www.ft.com/content/ebc10e76-da55-11e2-a237-00144feab7de; Alexei Anishchuk, “As Putin looks east, China and Russia sign $400-billion gas deal,” Reuters, May 21, 2014, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-russia-gas/as-putin-looks-east-china-and-russia-sign-400-billion-gas-deal-idUSBREA4K07K20140521; Georgi Kantchev, “China and Russia Are Partners—and Now Have a $55 Billion Pipeline to Prove It,” Wall Street Journal, December 1, 2019, https://www.wsj.com/articles/china-and-russia-are-partnersand-now-have-a-55-billion-pipeline-to-prove-it-11575225030.