October 3, 2020

Revisiting the U.S. role in NATO 30 years after German reunification

By John Cookson

Key points

- Europe is safe and secure three decades after German reunification. Many U.S. allies are wealthy, threats are few. Yet the U.S. continues its wasteful overinvestment in European security.

- Recent U.S. troop redeployments on the continent do not remedy the problem of U.S. overinvestment. Far fewer U.S. troops are needed in Europe today.

- Because it rankles relations with Moscow and creates huge security liabilities without benefitting U.S. interests, NATO expansion should halt, especially as to the possible membership of Ukraine and Georgia.

Reunification was a victory for NATO

October 3, 2020, marks 30 years since East and West Germany reunified. Less than a year before the countries merged, on November 9, 1989, East German border crossings were opened in Berlin. Many East Germans voted with their feet, pouring into West Germany. Then, in March 1990, the remaining East Germans voted at the ballot box, in the first and only real general election held in the German Democratic Republic (GDR). The center-right Christian Democrats ran on a platform of rapid reunification, and their victory propelled the process toward that end.1For more on German reunification and its relevance to today, see John Kampfner, Why the Germans Do It Better: Notes from a Grown-Up Country (London: Atlantic Books, 2020); Anne McElvoy, “Germany’s New Divisions: 30 Years on From Reunification, What’s Next?” Sunday Times, Sept. 27, 2020, https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/germanys-new-divisions-30-years-on-from-reunification-whats-next-7m9bs7zxf.

U.S. and Soviet officials met often during this period to discuss what a united Germany might mean for European security. More than 300,000 Soviet troops were stationed in the GDR at the time, and it was unclear upon reunification if East Germany would join West Germany in NATO or if another arrangement would be struck.

Over several months, the Americans and Soviets discussed an imaginative range of possibilities for Germany. Non-alignment and joining the Warsaw Pact were suggested by the Soviets, as was joining both NATO and the Warsaw Pact at the same time. Even the idea of the Soviet Union joining NATO along with a reunited Germany was floated by Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev.2James A. Baker, III, with Thomas M. DeFrank, The Politics of Diplomacy (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1995), 230–231, 237, 250–253.

Led by Secretary of State James Baker, the Americans were steadfast in arguing for a united Germany within NATO. To make the outcome more palatable, nine assurances were offered to Moscow, including that Soviet troops would be given adequate time to withdraw from East Germany. While the American side prevailed, Soviet inclusion in the talks helped Gorbachev fend off criticism from rivals within the USSR. Had the Soviet Union been excluded from talks, it is possible that opposition forces in Moscow might have exploited the opportunity to turn back reforms.

Russia is not the Soviet Union of the Cold War

Today, the U.S.-USSR discussions about German reunification remain a point of contention among scholars, policymakers, and even heads of state.3See Joshua R. Itzkowitz Shifrinson, “Deal or No Deal? The End of the Cold War and the U.S. Offer to Limit NATO Expansion,” International Security 40, No. 4 (Spring 2016), 7–44; Mark Kramer and Joshua R. Itzkowitz Shifrinson, “Correspondence: NATO Enlargement—Was There a Promise?” International Security, 42, No. 1 (Summer 2017), pp. 186–192; Steven Pifer, “Did NATO Promise Not to Enlarge? Gorbachev Says ‘No,’” Brookings Institution, Nov. 6, 2014, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2014/11/06/did-nato-promise-not-to-enlarge-gorbachev-says-no/; Kirk Bennett, “What Gorbachev Did Not Hear,” American Interest, March 12, 2018, https://www.the-american-interest.com/2018/03/12/gorbachev-not-hear/. The crux of the dispute is whether U.S. officials made a verbal assurance to the Soviets that if a unified Germany joined NATO, then the alliance would not expand further east past the German border.

It is clear that Baker told Gorbachev early in 1990 that NATO would move “not one inch eastward,”4Svetlana Savranskaya and Tom Blanton, “NATO Expansion: What Gorbachev Heard,” Briefing Book #613, National Security Archive, Dec. 12, 2017, https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/briefing-book/russia-programs/2017-12-12/nato-expansion-what-gorbachev-heard-western-leaders-early. but this has been taken by some to refer to military bases within West and East Germany. Gorbachev—no fan of NATO expansion, calling it a “big mistake”—has agreed with this view.”5Maxim Kórshunov, “Mikhail Gorbachev: I Am Against All Walls,” Russia Beyond, Oct. 16, 2014, https://www.rbth.com/international/2014/10/16/mikhail_gorbachev_i_am_against_all_walls_40673.html. But other Russian officials clearly believed they had been duped, and that view informs relations today.

Vladimir Putin, who was a KGB agent in East Germany when the Berlin Wall fell,6Chris Bowlby, “Vladimir Putin’s Formative German Years,” BBC News, March 27, 2015, https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-32066222. has since asserted that NATO’s expansion was a direct violation of promises made in 1990.7See “Speech and the Following Discussion at the Munich Conference on Security Policy,” Kremlin.ru, Feb. 10, 2007, http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/transcripts/24034; “Address by President of the Russian Federation,” Kremlin.ru, March 18, 2014, http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/20603. He has made this assertion not on its own, but together with the point that NATO’s expansion is a security threat to Russia.

One need not feel any warmth toward Russia’s leadership to appreciate the reality that NATO expansion, and the prospect of more, is a reasonable concern. NATO forces can now amass on Russia’s border, and that is a potential threat. But by yoking that potential threat to the idea of a broken promise, Putin creates the impression that the threat as unmistakable and unchanging. Be it in 1990 or 2020, Putin implies, NATO forces cannot be trusted to be defensive only when they possess offensive capability Russia cannot hope to match. That characteristic is fixed, and Russia is fixed against it.

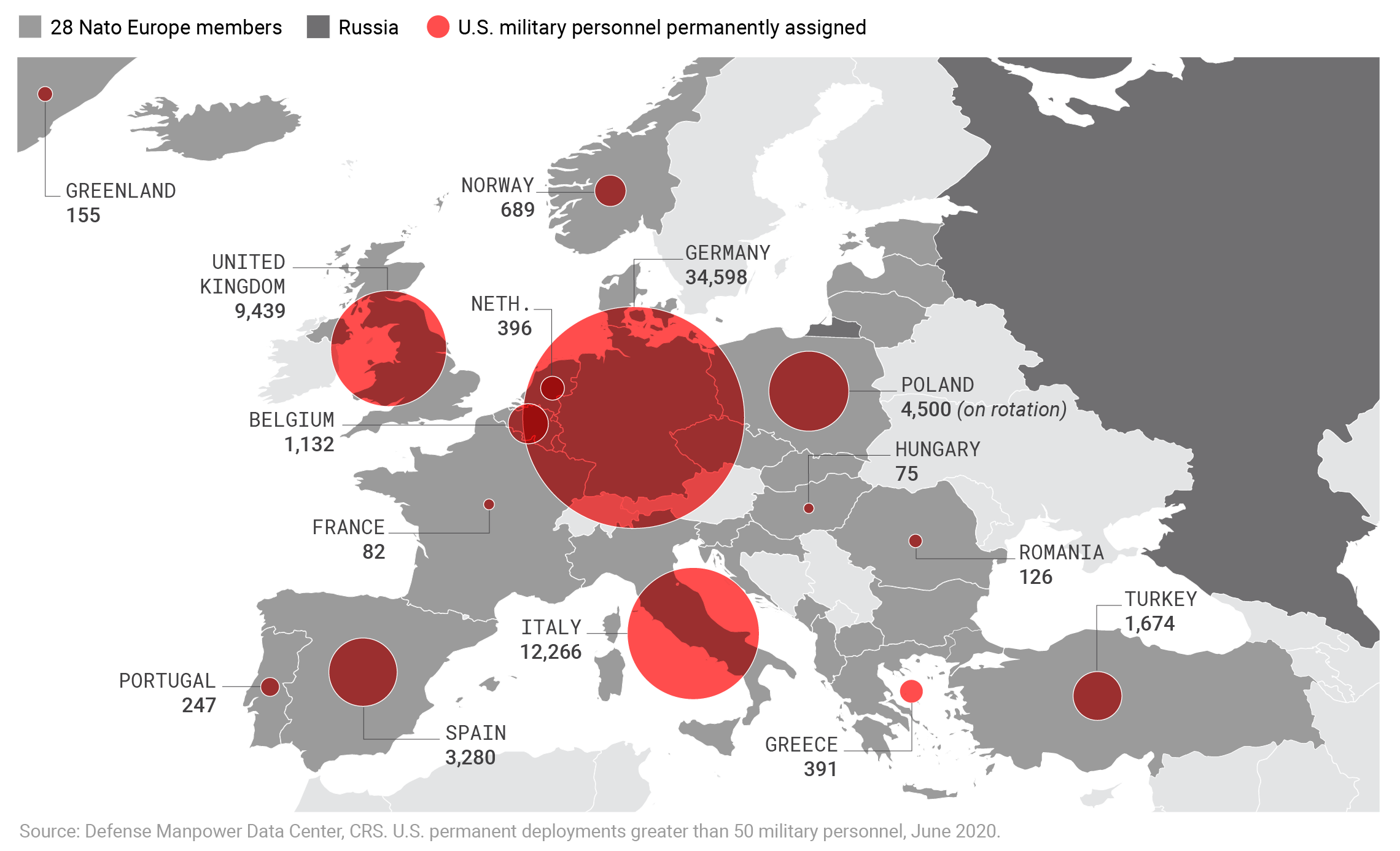

U.S. military forces in Europe

More than 70,000 U.S. military personnel are permanently deployed to Europe at present, with more on temporary deployments across the continent.

The question here is not what Putin believes, but why he often brings up issues from decades ago in this context. One answer is that returning to this assertion is a gambit to reconstrue relations between Moscow and the West.

Putin’s assertion of NATO duplicity and ill intent—on top of Russia’s reasonable security concerns—helps preserve an idea of a great geopolitical standoff between Russia and the West. This standoff imparts a prestige on Russia by implying a kind of parity with the West. Russia remains a force to be reckoned with, and all parties should behave accordingly. This implied parity masks the fact, however, that Russia now is a shadow of its former power as the Soviet Union.

The Cold War is over; the USSR crumbled. Moscow no longer commands military forces that credibly threaten to overrun the continent. In terms of conventional military power today, NATO Europe—all alliance members minus the U.S. and Canada—is a formidable counterweight to the one-time superpower. Together, European NATO nations spent more than four times what Russia did on defense last year.8Nan Tian, Alexandra Kuimova, Diego Lopes da Silva, Pieter D. Wezeman, and Siemon T. Wezeman, “Trends in World Military Expenditure, 2019,” Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, April 2020, https://www.sipri.org/publications/2020/sipri-fact-sheets/trends-world-military-expenditure-2019.

Even after an expensive modernization program following a problem-prone incursion in Georgia in 2008, Russia’s military today lacks the capacity for large-scale conquest and the international prestige such power confers.9Keith Crane, Olga Oliker, Brian Nichiporuk, “Trends in Russia’s Armed Forces” (Report No. RR-2573-A), Santa Monica, California: RAND Corporation, 2019, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR2573.html. Moscow is hemmed in. Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 was expensive, it diverted limited Russian resources, and it led to increased defense spending by some European NATO members.10Michael Kofman, “Russian Military Buildup in the West: Fact versus Fiction,” Russia File, Sept. 19, 2017, https://www.wilsoncenter.org/blog-post/russian-military-buildup-the-west-fact-versus-fiction; Kofman, et al., “Lessons from Russia’s Operations in Crimea and Eastern Ukraine,” (Report No. RR-1498-A), Santa Monica, California: RAND Corporation, 2017, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR1498.html. Furthermore, while Russia’s sizable nuclear arsenal is a deterrent against invasion and regime change, it is ineffective at compelling other nations to acquiesce to territorial conquest.11See Todd S. Sechser and Matthew Fuhrmann, Nuclear Weapons and Coercive Diplomacy, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017).

Russia poses no real threat of conquering the continent at present, with or without the current levels of U.S. forces permanently stationed there. NATO Europe countries are strong in conventional military power and, if necessary, have the means to grow even stronger through heavier spending or tighter integration.

Wealth is the basis of national power. The combined economies of NATO Europe are more than 10 times the size of Russia’s economy.12“World Economic Outlook, April 2020,” International Monetary Fund, April 6, 2020, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2020/04/14/weo-april-2020. Germany, the largest economy in Europe, is also “the large economy most likely to thrive in the post-pandemic world,” according to Ruchir Sharma, the chief global strategist at Morgan Stanley Investment Management.13Ruchir Sharma, “Which Country Will Triumph in the Post-Pandemic World?” New York Times, July 19, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/19/opinion/coronavirus-germany-economy.html.

In contrast, Russia has struggled to prop up its ailing economy, which is now the world’s 11th largest, behind Italy, Brazil, and Canada. Sustained low oil prices have deprived the government of revenue. The pandemic has damaged the Russian economy even further, to the extent that Moscow is looking to cut its defense spending by 5 percent next year to increase spending on social support ahead of Duma elections in 2021.14Henry Foy, “Russia to Cut Defence Spending in Bid to Prop up Ailing Economy,” Financial Times, September 21, 2020.

As always, a sober assessment of vital U.S. interests should determine U.S. strategy in Europe.

After World War II, NATO came into being to secure an impoverished Western Europe and to check Soviet expansion on the continent. Today, Russia is weak. Germany and other European NATO allies are wealthy and capable of shouldering more of the burden for their security.

Far fewer U.S. troops are needed in Germany and in Europe

The decision earlier this year to withdraw 12,000 of 36,000 U.S. troops from Germany drew animated responses from some policymakers and commentators in Washington. It was portrayed as an abandonment of Germany and Europe by the United States.15See R.D. Hooker, Jr., “A Potentially Deadly Blow to NATO,” Defense One, Sept. 29, 2020, https://www.defenseone.com/ideas/2020/09/potentially-deadly-blow-nato/168853/; Joe Gould, “Congress Moves to Block Trump’s Germany Troop Withdrawal Plans,” Defense News, June 30, 2020, https://www.defensenews.com/congress/2020/06/30/congress-moves-to-block-trumps-germany-troop-withdrawal-plans/; Judy Dempsey, “Why Pulling U.S. Troops Out of Germany Damages America,” Strategic Europe, June 18, 2020, https://carnegieeurope.eu/strategiceurope/82099; Nic Robertson, “Trump’s Germany Troops Pullout May Be His Last Gift to Putin Before the Election,” CNN, Aug. 2, 2020, https://www.cnn.com/2020/08/02/politics/trump-germany-troops-russia-intl/index.html.

Hardly. Of the U.S. troops being moved out of Germany, 5,600 are staying in Europe. The 6,400 U.S. troops leaving Europe make up less than one-tenth of the total permanent U.S. military presence on the continent. Some 24,000 U.S. troops will remain in Germany. A thousand troops headed from Germany to Poland offer no net difference in terms of NATO security against Russia in Europe. Large U.S. force deployments remain in Italy, Spain, the UK, and Turkey, with smaller deployments spread throughout the continent.

The justifications that supported massive numbers of U.S. troops in Europe no longer exist today. It should not cause outrage to suggest that half or less of the current U.S. military presence on the continent is warranted. After all, the number of U.S. troops in Europe has fallen by more than that share already since the end of the Cold War. Not only is Europe today safe and capable of shouldering more of the burden for its own defense, but also planned U.S. drawdowns in Afghanistan and Iraq mean airbases in Europe will require fewer U.S. personnel going forward.

Reducing the number of U.S. troops on the continent would encourage European NATO members to modernize their militaries and work to solve interoperability issues that have plagued the great powers there. That most European NATO members spend less than 2 percent of their GDP on defense has routinely drawn criticism from Washington, and European free-riding on U.S. largess is indeed an issue to be addressed. But even if European allies do not increase their spending after a U.S. reduction, their current strength puts them in an enviable position for deterring Russia from territorial conquest.

Meanwhile, reducing the U.S. military presence in Europe will save U.S. taxpayers money—resources which can be freed up for higher priorities. Any short-term costs for redeployment would pale in comparison to the savings from reorienting long-term spending toward better investments, be they for U.S. security or otherwise.

The raw number of American troops in Europe at any one time is not a measure of the U.S. commitment to NATO’s Article 5. The two issues are separate, and the number of U.S. troops should be a reflection of U.S. security concerns and the balance of power in Eurasia. The American public seems to intuit this point. A majority of Americans favor decreasing the U.S. troop presence in Germany (57 percent), and an additional 16 percent say that all troops should be withdrawn, according to a recent poll by the Chicago Council on Global Affairs.16Dina Smeltz, Ivo H. Daalder, Karl Friedhoff, Craig Kafura, and Brendan Helm, “Divided We Stand,” Chicago Council on Global Affairs, https://www.thechicagocouncil.org/publication/lcc/divided-we-stand.

NATO should halt expansion

For Germany and for NATO, 1990 was the Wende, or the turning point, leading to expansion. Whether or not the Americans made a promise to the Soviets then, the alliance did grow in the intervening years, to 30 nations and to Russia’s borders today.

Further expansion should stop. Extending U.S. security guarantees ever eastward within NATO is unwise and dangerous. It dilutes the credibility of security commitments. The American public cannot be expected to support sending U.S. troops to fight and die for Podgorica and Skopje, the newest NATO allies. Washington promising American troops would be sent there—and potentially to more new allies soon—in response to an attack puts all U.S. security commitments into question. Polling already finds that around half of Americans do not support using U.S. troops to defend current Baltic allies from a Russian invasion, a share likely to increase should such a scenario become a reality.17Ibid.

Another reason to halt expansion is that politics in Eastern Europe is much more evenly split and contentious between facing toward the West or toward Russia. Extending security guarantees to countries ambivalent or changeable in orientation invites blowback. For example, recent elections in Montenegro, which joined NATO in 2017, saw the rise to power of a pro-Russian political party.18Ivana Stradner and Milan Jovanović, “Montenegro Is the Latest Domino to Fall Toward Russia,” Foreign Policy, September 17, 2020, https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/09/17/montenegro-latest-domino-fall-russia-pro-west-europe-nato/.

NATO is also diluting what membership means by creating quasi-memberships and military partnerships. Earlier this year, NATO recognized Ukraine as an Enhanced Opportunities Partner, a designation shared with Georgia. NATO members conduct military exercises with both. In doing so, Kyiv and Tbilisi are led to believe they are next in line for full membership. American and NATO leaders do little to disabuse them of this notion; many encourage it. In doing so, the U.S. and NATO undermine the credibility of their real security commitments by blurring the distinction between alliance members and non-members.

In fact, ongoing conflicts in contested regions and reasonable concerns about the defensibility of both Ukraine and Georgia—both on Russia’s border—should preclude their joining NATO. Neutrality is a more reasonable course.19Mike Sweeney, “Saying ‘No’ to NATO—Options for Ukrainian Neutrality,” Defense Priorities, August 2020, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/saying-no-to-nato-options-for-ukrainian-neutrality. The prospect of European Union membership can still be used to entice Eastern European countries to orient politics toward the West, but NATO membership and the U.S. security guarantee it entails should be removed from consideration. Further expansion invites unnecessary risks for no real benefit to the U.S. or current allies.

Europe is a different continent than it was in 1990. Germany, along with many of its allies, is wealthy and capable of shouldering a larger burden for defense—or of deciding that it does not need as much protection, whether it comes from the U.S. or its own resources. A residual Cold War mentality, 30 years after German reunification, should not be permitted to undermine U.S. security and prosperity for the next 30 years. Toward this end, the U.S. should station fewer U.S. troops on the continent and halt the extension of new U.S. security guarantees through NATO.

Endnotes

- 1For more on German reunification and its relevance to today, see John Kampfner, Why the Germans Do It Better: Notes from a Grown-Up Country (London: Atlantic Books, 2020); Anne McElvoy, “Germany’s New Divisions: 30 Years on From Reunification, What’s Next?” Sunday Times, Sept. 27, 2020, https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/germanys-new-divisions-30-years-on-from-reunification-whats-next-7m9bs7zxf.

- 2James A. Baker, III, with Thomas M. DeFrank, The Politics of Diplomacy (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1995), 230–231, 237, 250–253.

- 3See Joshua R. Itzkowitz Shifrinson, “Deal or No Deal? The End of the Cold War and the U.S. Offer to Limit NATO Expansion,” International Security 40, No. 4 (Spring 2016), 7–44; Mark Kramer and Joshua R. Itzkowitz Shifrinson, “Correspondence: NATO Enlargement—Was There a Promise?” International Security, 42, No. 1 (Summer 2017), pp. 186–192; Steven Pifer, “Did NATO Promise Not to Enlarge? Gorbachev Says ‘No,’” Brookings Institution, Nov. 6, 2014, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2014/11/06/did-nato-promise-not-to-enlarge-gorbachev-says-no/; Kirk Bennett, “What Gorbachev Did Not Hear,” American Interest, March 12, 2018, https://www.the-american-interest.com/2018/03/12/gorbachev-not-hear/.

- 4Svetlana Savranskaya and Tom Blanton, “NATO Expansion: What Gorbachev Heard,” Briefing Book #613, National Security Archive, Dec. 12, 2017, https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/briefing-book/russia-programs/2017-12-12/nato-expansion-what-gorbachev-heard-western-leaders-early.

- 5Maxim Kórshunov, “Mikhail Gorbachev: I Am Against All Walls,” Russia Beyond, Oct. 16, 2014, https://www.rbth.com/international/2014/10/16/mikhail_gorbachev_i_am_against_all_walls_40673.html.

- 6Chris Bowlby, “Vladimir Putin’s Formative German Years,” BBC News, March 27, 2015, https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-32066222.

- 7See “Speech and the Following Discussion at the Munich Conference on Security Policy,” Kremlin.ru, Feb. 10, 2007, http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/transcripts/24034; “Address by President of the Russian Federation,” Kremlin.ru, March 18, 2014, http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/20603.

- 8Nan Tian, Alexandra Kuimova, Diego Lopes da Silva, Pieter D. Wezeman, and Siemon T. Wezeman, “Trends in World Military Expenditure, 2019,” Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, April 2020, https://www.sipri.org/publications/2020/sipri-fact-sheets/trends-world-military-expenditure-2019.

- 9Keith Crane, Olga Oliker, Brian Nichiporuk, “Trends in Russia’s Armed Forces” (Report No. RR-2573-A), Santa Monica, California: RAND Corporation, 2019, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR2573.html.

- 10Michael Kofman, “Russian Military Buildup in the West: Fact versus Fiction,” Russia File, Sept. 19, 2017, https://www.wilsoncenter.org/blog-post/russian-military-buildup-the-west-fact-versus-fiction; Kofman, et al., “Lessons from Russia’s Operations in Crimea and Eastern Ukraine,” (Report No. RR-1498-A), Santa Monica, California: RAND Corporation, 2017, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR1498.html.

- 11See Todd S. Sechser and Matthew Fuhrmann, Nuclear Weapons and Coercive Diplomacy, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017).

- 12“World Economic Outlook, April 2020,” International Monetary Fund, April 6, 2020, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2020/04/14/weo-april-2020.

- 13Ruchir Sharma, “Which Country Will Triumph in the Post-Pandemic World?” New York Times, July 19, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/19/opinion/coronavirus-germany-economy.html.

- 14Henry Foy, “Russia to Cut Defence Spending in Bid to Prop up Ailing Economy,” Financial Times, September 21, 2020.

- 15See R.D. Hooker, Jr., “A Potentially Deadly Blow to NATO,” Defense One, Sept. 29, 2020, https://www.defenseone.com/ideas/2020/09/potentially-deadly-blow-nato/168853/; Joe Gould, “Congress Moves to Block Trump’s Germany Troop Withdrawal Plans,” Defense News, June 30, 2020, https://www.defensenews.com/congress/2020/06/30/congress-moves-to-block-trumps-germany-troop-withdrawal-plans/; Judy Dempsey, “Why Pulling U.S. Troops Out of Germany Damages America,” Strategic Europe, June 18, 2020, https://carnegieeurope.eu/strategiceurope/82099; Nic Robertson, “Trump’s Germany Troops Pullout May Be His Last Gift to Putin Before the Election,” CNN, Aug. 2, 2020, https://www.cnn.com/2020/08/02/politics/trump-germany-troops-russia-intl/index.html.

- 16Dina Smeltz, Ivo H. Daalder, Karl Friedhoff, Craig Kafura, and Brendan Helm, “Divided We Stand,” Chicago Council on Global Affairs, https://www.thechicagocouncil.org/publication/lcc/divided-we-stand.

- 17Ibid.

- 18Ivana Stradner and Milan Jovanović, “Montenegro Is the Latest Domino to Fall Toward Russia,” Foreign Policy, September 17, 2020, https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/09/17/montenegro-latest-domino-fall-russia-pro-west-europe-nato/.

- 19Mike Sweeney, “Saying ‘No’ to NATO—Options for Ukrainian Neutrality,” Defense Priorities, August 2020, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/saying-no-to-nato-options-for-ukrainian-neutrality.

More on Europe

October 17, 2025

By Geoff LaMear

October 11, 2025

Events on NATO