January 21, 2025

Achieving burden-sharing: Retrenchment vs. conditionality

Key points

- Observers and practitioners are frequently frustrated at the level of defense burden-sharing in U.S. alliances—alliance members’ contributions to collective defense objectives—and particularly at allies’ low level of investment in their own defense.

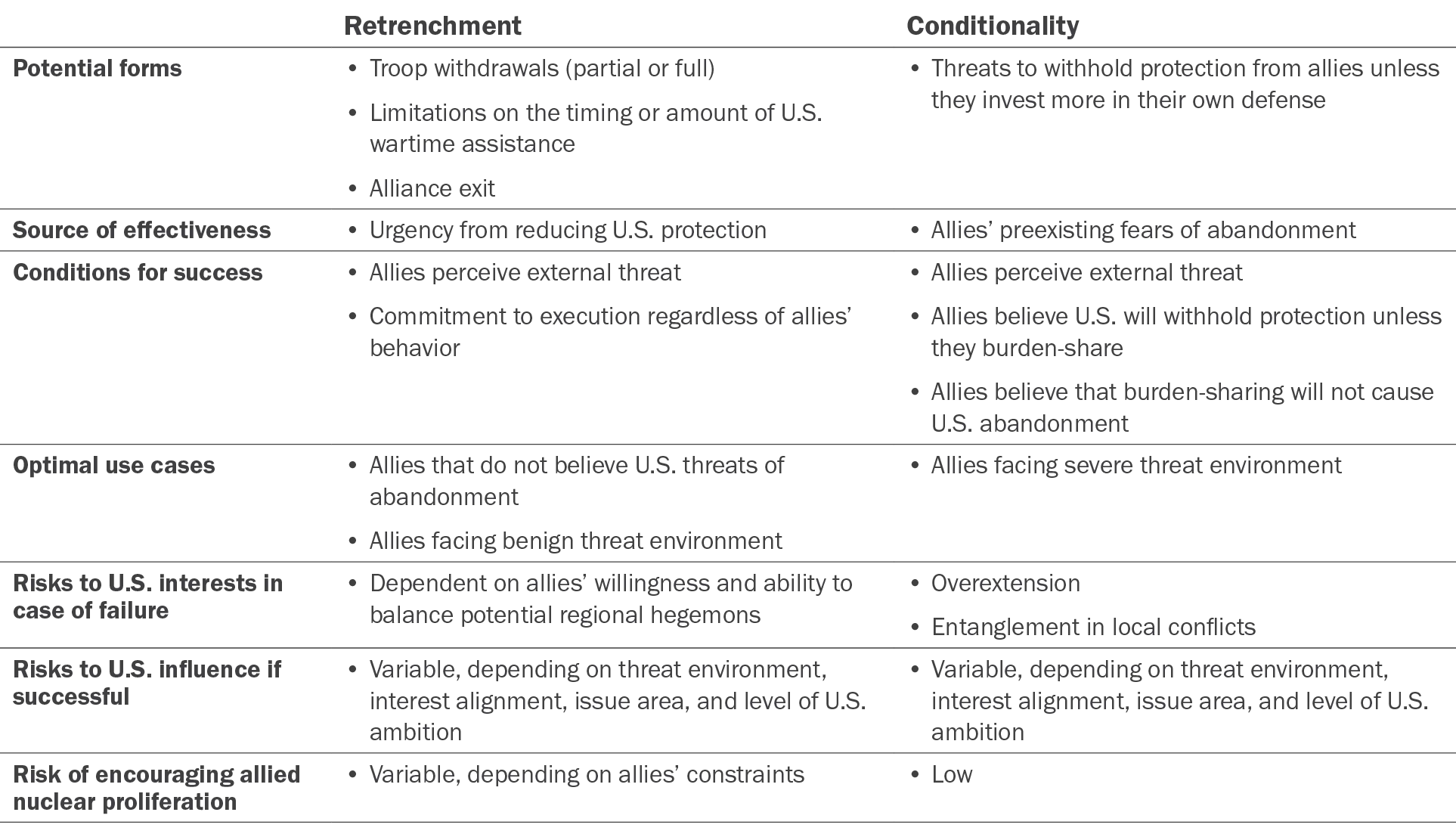

- This paper compares two approaches to soliciting burden-sharing in U.S. alliances: retrenchment and conditionality. Retrenchment refers to reductions in the amount or timing of wartime assistance the United States will provide to allies, including troop withdrawals. Conditionality, in turn, relies on threats to abandon allies unless they increase their defense efforts and does not necessarily entail reducing protection.

- Retrenchment may offer the greatest chance of success, particularly in cases where allies doubt the credibility of the United States’ threats to abandon them. Conditionality is likely to be nearly as effective as retrenchment in many other cases, particularly those in which allies take the U.S. threat of abandonment seriously and there is a compelling external threat.

- Retrenchment and conditionality can be complementary strategies. Retrenchment is effective in cases where conditionality is likely to fail, while conditionality is effective in cases where the United States might be unwilling to retrench due to fears that a revisionist power might seek regional hegemony.

- Burden-sharing is not without its downsides, including allies potentially desiring nuclear weapons. These risks might be greater if the United States retrenches but may not materialize in practice and are not necessarily insurmountable.

The perennial importance—and challenges—of burden-sharing

Few issues in American alliances are as evergreen as defense burden-sharing. Sharing the costs of collective defense with allies is the central mechanism by which the United States can marshal sufficient military power to deter and defeat adversaries without furnishing the costs of doing so alone. Burden-sharing is particularly important in an era when the United States faces tradeoffs not only in the deployment of its existing resources between Europe, Asia, and the Middle East, but also in the development and procurement of future capabilities.1Brian Blankenship, “Managing the Dilemmas of Alliance Burden Sharing,” Washington Quarterly 47, no. 1 (2024): 41–61, https://doi.org/10.1080/0163660X.2024.2323898.

However, burden-sharing is also among the most perennially contentious sore spots in U.S. alliances. While often associated with incoming president Donald Trump, who repeatedly cast doubt on his willingness to defend allies that did not pay their “fair share,” American officials regularly express frustration that allies do not spend more on defense. Secretary of Defense Robert Gates, for example, warned NATO in 2011 that “there will be dwindling appetite and patience… to expend increasingly precious funds on behalf of nations that are apparently unwilling to devote the necessary resources… to be serious and capable partners in their own defense.”2Michael Birnbaum, “Gates Rebukes European Allies in Farewell Speech,” Washington Post, June 10, 2011, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/gates-rebukes-european-allies-in-farewell-speech/2011/06/10/AG9tKeOH_story.html.

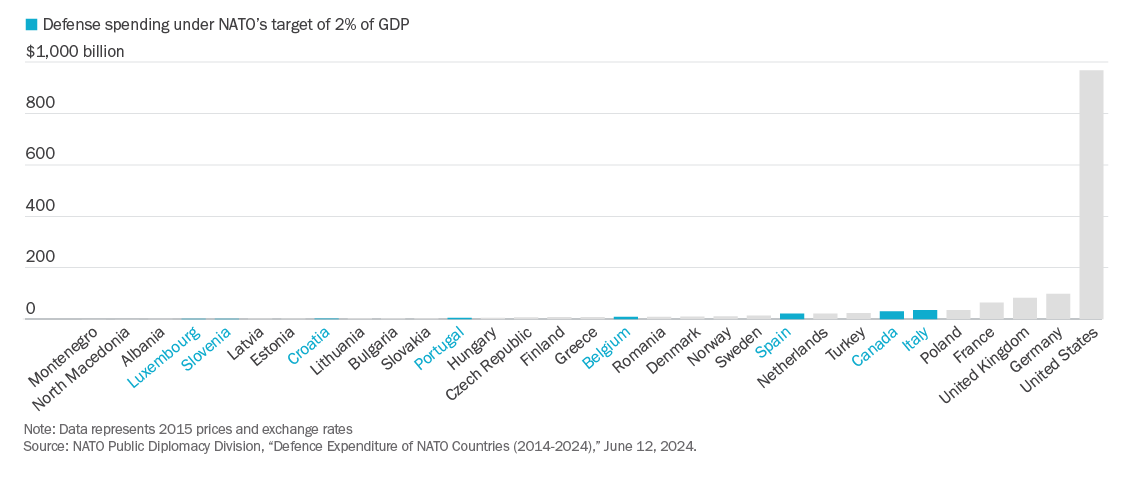

Defense spending in NATO countries, 2024

The United States spends by far the most on national defense of any NATO nation.

The barriers to encouraging allies to assume more responsibility for their defense are well-understood. First, allies may not agree in their perceptions of threats—either with each other’s perceptions or with those of the United States. This can result from idiosyncratic variation in assessment of adversary capabilities or intentions, but it can also stem more systematically from differences in geography.3Keren Yarhi-Milo, Knowing the Adversary: Leaders, Intelligence, and Assessment of Intentions in International Relations (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2014). West Germany, for example, was more amenable to investing in defense during the Cold War than much of Western Europe due to its land border with the Warsaw Pact.4Brian Blankenship, The Burden-Sharing Dilemma: Coercive Diplomacy in US Alliance Politics (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2023). Allies that do not perceive a threat as worthy of counterbalancing, in turn, are unlikely to invest significantly more in defense.

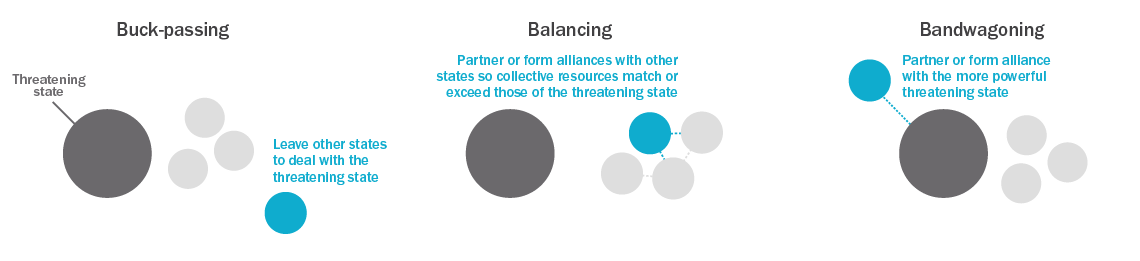

Second, even if allies do perceive a substantial external threat, they may be tempted to “buck-pass”—to let the United States or other allies assume the costs of dealing with potential threats.5Mancur Olson Jr. and Richard Zeckhauser, “An Economic Theory of Alliances,” Review of Economics and Statistics 48, no. 3 (1966): 266–79; John J. Mearsheimer, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics (New York: W.W. Norton, 2001). This temptation is likely to be greater among allies that have more confidence that the United States will defend them, such as those that host large numbers of U.S. forces or which are strategically valuable to American interests.6David A. Lake, Entangling Relations: American Foreign Policy in Its Century (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1999); David A. Lake, Hierarchy in International Relations (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2009); Brian Blankenship, “The Price of Protection: Explaining Success and Failure of US Alliance Burden-Sharing Pressure,” Security Studies 30, no. 5 (2021): 691–724.

Given these challenges, this paper explores the United States’ options for successfully encouraging allies to burden-share. Importantly, advocates may seek burden-sharing for different reasons. The first is the pursuit of a more equitable status quo, in which U.S. security commitments remain largely unchanged but allies increase their capacity for self-defense.7Mira Rapp-Hooper, “Saving America’s Alliances: The United States Still Needs the System That Put It on Top,” Foreign Affairs 99, no. 2 (2020): 127–40. The second is prioritization, with the United States reducing some commitments to double down on others and leaving allies to fill the gap. “Prioritizers” favor devoting more resources to Asia and fewer to Europe and the Middle East.8Alex Velez-Green and Robert Peters, “The Prioritization Imperative: A Strategy to Defend America’s Interests in a More Dangerous World,” Heritage Foundation, August 1, 2024, https://www.heritage.org/defense/report/the-prioritization-imperative-strategy-defend-americas-interests-more-dangerous. Finally, advocates of restraint propose scaling back U.S. commitments and leaving allies to balance against local threats largely on their own.9Barry R. Posen, Restraint: A New Foundation for U.S. Grand Strategy (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2014). For “restrainers,” burden-sharing is at best an interim goal en route to allies becoming capable of defending themselves with little to no U.S. involvement (“burden-shifting”). Indeed, many restrainers do not view greater burden-sharing as a prerequisite to reducing U.S. commitments on the grounds that the threat environment is not that severe.10Rajan Menon, “Reconfiguring NATO: The Case for Burden Shifting,” Defense Priorities, May 2, 2024, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/reconfiguring-nato/; Benjamin Friedman, “A New NATO Agenda: Less U.S., Less Dependency,” Defense Priorities, July 8, 2024, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/a-new-nato-agenda/. This paper is ultimately agnostic about these larger objectives, and instead focuses on the effectiveness of competing approaches.

Specifically, this paper compares two approaches to promoting defense burden-sharing in American alliances: retrenchment and conditionality. These are not exhaustive. Other approaches are possible, including intra-alliance negotiations to create clear burden-sharing targets that can be used to hold allies accountable, such as NATO’s 2 percent of GDP spending target, or efforts to “name and shame” allies that underinvest in defense.11Jordan Becker et al., “Transatlantic Shakedown: Presidential Shaming and NATO Burden Sharing,” Journal of Conflict Resolution, April 21, 2023, 00220027231167840, https://doi.org/10.1177/00220027231167840; Jordan Becker, “Pledge and Forget? Testing the Effects of NATO’s Wales Pledge on Defense Investment,” International Studies Perspectives, January 23, 2024, ekad027, https://doi.org/10.1093/isp/ekad027; Brian Blankenship, “Do Threats or Shaming Increase Public Support for Policy Concessions? Alliance Coercion and Burden-Sharing in NATO,” International Studies Quarterly 68, no. 2 (2024): sqae015. But what they have in common that distinguishes them from competing approaches is that they are attempts to shape allies’ incentives to invest in self-defense, rather than appeal to allies’ senses of fairness, shame, or obligation.

At its most ambitious, retrenchment would entail wholesale U.S. troop withdrawals from abroad and clear signals that the United States will leave allies responsible for defending themselves. In a more modest form, Washington could withdraw some forces and signal limits on the amount of assistance it would furnish. Conditionality would stop short of immediate retrenchment and instead employ threats to withhold or reduce U.S. assistance unless allies invest more in defense.

Each approach presents a different balance of potential risks and rewards. Retrenchment avoids many of conditionality’s pitfalls as it obviates questions about the credibility of U.S. threats to withhold protection. But conditionality is likely to be effective in cases where decision-makers are reluctant to retrench due to the presence of a potential regional hegemon. In the following pages, I describe each of these approaches and evaluate their effectiveness and risks.

Retrenchment

Retrenchment can vary widely in its form and extent. At its mildest, retrenchment entails partial troop withdrawals without changes in the level of political or military commitment. At its most extensive, retrenchment can take the form of not only total troop withdrawals, but also cessations of political and military commitments. The latter can be de facto—for example, abandoning plans to defend allies or repurposing forces useful for their defense—or de jure—exiting the alliance outright.

In its more modest forms, retrenchment can imply reducing but not eliminating commitments, as in the case of the “Nixon Doctrine,” which pledged that the United States would keep its treaty commitments but look to allies to assume the primary role in their defense. During his initial remarks in Guam in July 1969, Nixon declared that “as far as the problems of military defense… the United States is going to encourage and has a right to expect that this problem will be increasingly handled by, and the responsibility for it taken by, the Asian nations themselves.”12Richard Nixon, “Informal Remarks in Guam With Newsmen,” American Presidency Project, July 25, 1969, https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/informal-remarks-guam-with-newsmen.

Burden-sharing is hardly the only goal that retrenchment’s advocates have in mind. Most directly, retrenchment is an avenue to cost-cutting.13Paul K. MacDonald and Joseph M. Parent, Twilight of the Titans: Great Power Decline and Retrenchment (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2018). Similarly, retrenchment can be a means to ameliorate the security dilemma and alleviate tensions with adversaries, provided their intentions are not inalterably expansionist.14Brandon K. Yoder, “Retrenchment as a Screening Mechanism: Power Shifts, Strategic Withdrawal, and Credible Signals,” American Journal of Political Science 63, no. 1 (2019): 130–45, https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12395. Finally, retrenchment may reduce the risk of U.S. involvement in local conflicts, shifting the defense burden onto allies.15Posen, Restraint.

When it comes to burden-sharing, retrenchment’s main appeal is in generating urgency. Withdrawing foreign-deployed forces, communicating limits on the amount of wartime assistance allies can expect, or exiting an alliance presents U.S. allies with a fait accompli. This removes any doubts allies might have about the United States’ willingness to do so and puts them in a position of having to choose how they react to reduced or eliminated U.S. protection. Moreover, it obliges them to react immediately, rather than allowing them to stall for time in case U.S. retrenchment never occurs. Indeed, there is some empirical evidence that both alliances and U.S. troop levels may reduce partner defense spending on the margin, though the finding is not universal.16Carla Martínez Machain and T. Clifton Morgan, “The Effect of US Troop Deployment on Host States’ Foreign Policy,” Armed Forces & Society 39, no. 1 (2013): 102–23; Lake, Hierarchy in International Relations; Matthew Digiuseppe and Paul Poast, “Arms versus Democratic Allies,” British Journal of Political Science 48, no. 4 (2018): 981–1003; Matthew DiGiuseppe and Patrick E. Shea, “Alliances, Signals of Support, and Military Effort,” European Journal of International Relations 27, no. 4 (2021): 1067–89.

Conditionality

Whereas retrenchment would entail unilateral changes in U.S. commitments regardless of allies’ behavior, conditionality instead relies upon threats to reduce the protection allies receive from the United States unless they invest more in defense. As with retrenchment, these threats can take a variety of forms—from troop withdrawals to limits on the amount or timing of U.S. assistance to outright alliance exit.17Blankenship, The Burden-Sharing Dilemma.

The basic logic of conditionality is to leverage allies’ needs for protection and fears of abandonment. For maximal effectiveness, conditionality must combine three elements. The first is credibility: allies must believe there is at least some chance the United States will follow through on its threats. The second is impact: the cost of fighting an adversary without U.S. support must be high. The more credible and impactful the threat, the more effective it will be. Of the two, impact is the more important, as even a low probability of abandonment is a cause for concern if the cost of being abandoned is high—for example, if an ally shares a land border with a much more powerful adversary.18Blankenship, “The Price of Protection.” The third is reassurance: allies are more likely to change their behavior if they trust they will not be abandoned once they comply with U.S. demands.19Thomas Schelling, Arms and Influence (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1966).

There is a good deal of evidence that when these conditions are met, conditionality can be quite effective. Case studies drawn from U.S. coercive diplomacy during the Cold War, for example, suggest that the United States has been more successful in wielding threats when allies fear abandonment and have a greater perception of external threat.20Songying Fang and Kristopher W. Ramsay, “Outside Options and Burden Sharing in Nonbinding Alliances,” Political Research Quarterly 63, no. 1 (2010): 188–202; Blankenship, The Burden-Sharing Dilemma. During the early 1970s, for example, the Nixon administration used congressional calls for withdrawing U.S. forces from Europe to make the case that NATO allies’ best hope of forestalling withdrawals was to increase defense spending. Nixon argued in a meeting with NATO officials that “were the NATO partners to do more in their own defense, that would be quite decisive in firming up US support for making our present contribution to the Alliance.”21Report on a NATO Commanders Meeting, September 30, 1970, Foreign Relations of the United States, 1969–1976, vol. 41, document 48. The result was increased defense spending, particularly by West Germany.22Blankenship, The Burden-Sharing Dilemma, chapter 2.

There is likewise quantitative evidence that allies spend more on defense when U.S. threats of abandonment are more credible and impactful.23Blankenship, “The Price of Protection.” Finally, survey data suggest that threats of abandonment may also increase public support for higher defense spending in allied countries.24Blankenship, “Do Threats or Shaming Increase Public Support for Policy Concessions?”

Comparing the two strategies

Retrenchment and conditionality each have advantages but also face challenges that can limit their effectiveness. Retrenchment’s primary challenge comes from sequencing. In cases where there is a powerful, proximate shared adversary, the United States might prefer to fully execute its withdrawal after allies have sufficiently improved their own capabilities to avoid the adversary taking advantage.25 Joshua Byun, “Stuck Onshore: Why the United States Failed to Retrench from Europe during the Early Cold War,” Texas National Security Review 7, no. 4 (July 2, 2024), https://tnsr.org/2024/07/stuck-onshore-why-the-united-states-failed-to-retrench-from-europe-during-the-early-cold-war/. But facing such a scenario, allies have incentive to drag their feet and delay improving their military capabilities to prevent U.S. withdrawal.26As Henry Kissinger put it: “The greater the pressures for troop withdrawals in the United States, the greater the disinclination of our allies to augment their military establishments lest they justify further American withdrawals.” Henry Kissinger, White House Years (Boston, MA: Little, Brown, and Company, 1979), 394.

This sequencing problem makes a “graceful exit”—one where allies seamlessly do more as the United States does less—difficult. To offset allies’ incentive to delay force improvements in the hopes of forestalling U.S. withdrawal, retrenchment must either be executed swiftly and decisively or, if done gradually, must be credibly committed to. Doing so is difficult, as withdrawal plans may be derailed either by external events or internal opposition, as in the case of Jimmy Carter’s failed attempt to withdraw ground forces from South Korea.27Peter Harris, Why America Can’t Retrench (And How It Might) (Polity, 2024); Christopher S. Chivvis et al., “Strategic Change in U.S. Foreign Policy,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, July 23, 2024, https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2024/07/strategic-change-us-foreign-policy. But by building internal consensus and publicly committing to following through, leaders may be able to make retrenchment more credible. For example, even though Carter’s withdrawal plan was thwarted by opposition from within his administration and Congress, along with revised estimates of North Korean military strength, the South Koreans worried enough to substantially increase defense spending in part because Carter had promised withdrawal during his campaign.28Blankenship, The Burden-Sharing Dilemma, 105–7.

Conditionality poses three challenges of its own. The first is that allies may not view U.S. threats of abandonment as credible. This may in some cases be beyond American control, reflecting allies’ assessments of U.S. interest in their survival. But it may also be the result of American behavior, including pro-alliance rhetoric intended to reassure allies.29Brian Blankenship, “Promises under Pressure: Statements of Reassurance in US Alliances,” International Studies Quarterly 64, no. 4 (2020): 1017–30. Joe Biden, for example, frequently refers to U.S. commitments as “sacred.”30“Remarks by President Biden on the 75th Anniversary of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization Alliance,” July 9, 2024, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2024/02/13/biden-trump-nato-unamerican/.

The second is that allies may expect that the United States will simply abandon them after they have made sufficient investments in self-defense. If they believe their burden-sharing will simply facilitate U.S. withdrawal, they are more likely to refuse. The solution to this challenge is the inverse of retrenchment’s sequencing problem: to conditionally promise that the United States will not abandon the partner if it assumes more responsibility for its own defense.31Reid B. C. Pauly, “Damned If They Do, Damned If They Don’t: The Assurance Dilemma in International Coercion,” International Security 49, no. 1 (2024): 91–132, https://doi.org/10.1162/isec_a_00488.

Finally, conditionality requires frequent renegotiation. Changing circumstances, including shifts in allies’ willingness and ability to fulfill previous burden-sharing targets and in U.S. desire for greater allied contributions, can upend previous bargains. Because allies know that any bargain struck is temporary, and because they cannot be sure the United States will not continue to escalate its demands over time, they may wish to dig in their heels to deter future demands.32James D. Fearon, “Bargaining, Enforcement, and International Cooperation,” International Organization 52, no. 2 (1998): 269–305; Todd S. Sechser, “Goliath’s Curse: Coercive Threats and Asymmetric Power,” International Organization 64, no. 4 (2010): 627–60. Long-term use of conditionality may also tempt allies to view U.S. threats as bluffs.

As detailed above, there is a good deal of empirical evidence that both retrenchment and conditionality can be effective in stimulating burden-sharing, though there is little evidence that directly compares the two. In general, however, the two approaches are likely to be similarly effective because they share a similar precondition for effectiveness: that allies perceive a sufficient level of external threat. Neither retrenchment nor conditionality is likely to persuade countries that do not face a compelling threat to their security.

Of course, threat plays a dual role when it comes to burden-sharing. If the threat level is too high, then the United States may be unwilling to abandon allies for fear of allowing adversaries to make a serious bid for regional hegemony. The situations most conducive to burden-sharing, then, are those where allied perceptions of threat exceed those of the United States.33Blankenship, The Burden-Sharing Dilemma.

There are cases where one of the two strategies may be preferable. Retrenchment’s advantages are that it generates urgency, does not rely on allies believing in its credibility, and does not require frequent renegotiation. More so than conditionality, retrenchment decisively shifts the burden of defense onto allies and leaves little ambiguity about U.S. willingness to follow through.

Retrenchment may thus be particularly effective in two kinds of cases. The first are those where allies doubt the credibility of U.S. threats—for example, if an ally overestimates its strategic value or the amount of support it has in U.S. domestic politics. The second are those where the threat environment is benign. In such cases, even though allies are unlikely to invest more in defense if the United States withdraws, retrenchment may sow the seeds for future burden-sharing. That is, the United States can withdraw while the environment is favorable, giving allies incentive to adapt as the security environment changes and avoiding a future scenario in which it attempts to withdraw after the security environment has already deteriorated and allies have failed to adapt due to its protection.

Retrenchment and conditionality compared

There are also cases in which conditionality may be nearly if not equally effective—particularly those where allies have a powerful, proximate adversary. In such cases, the disadvantages of conditionality relative to retrenchment narrow, as the urgency of the external threat makes arming more attractive even if the United States does not retrench. This is especially true for allies that border their adversary by land due to the risk that they might be invaded and lose substantial amounts of territory or even independence before the United States intervenes.34Blankenship, “The Price of Protection.” Similarly, if allies view U.S. threats of abandonment as maximally credible, then conditionality may yield results similar to retrenchment.

Ultimately, the two strategies’ effectiveness is likely similar in most cases. Indeed, a mixed strategy that combines elements of both may be able to offset some of the challenges of each. Allies may be more likely to take U.S. threats of abandonment more seriously after a partial troop withdrawal, for example. The United States had a great deal of success encouraging South Korea to move toward self-reliance during the 1970s by withdrawing the Seventh Infantry Division in 1971 and wielding threats of more withdrawals.35Blankenship, The Burden-Sharing Dilemma, 92–107.

Evaluating burden-sharing’s risks

Attempts to solicit burden-sharing are not costless or without risk. A skeptic might offer at least three critiques. The first is that these approaches might fail to meaningfully encourage allies to invest in self-defense. Second, these approaches might succeed, but in doing so cede influence over U.S. allies. Third, efforts to pass the conventional defense burden onto allies may undermine efforts to curtail nuclear proliferation. I evaluate each in turn.

The risks of failure

The first risk is that efforts to encourage allied burden-sharing via either conditionality or retrenchment may fail. Of the two strategies described above, the consequences of failure are likely to be magnified by retrenchment, which may embolden and enable an adversary to make a serious bid for regional hegemony that ultimately draws the United States back in under less favorable circumstances.36Paul C. Avey, Jonathan N. Markowitz, and Robert J. Reardon, “Do US Troop Withdrawals Cause Instability? Evidence from Two Exogenous Shocks on the Korean Peninsula,” Journal of Global Security Studies 3, no. 1 (January 1, 2018): 72–92, https://doi.org/10.1093/jogss/ogx020.

Failure to arouse burden-sharing might stem from two sources. First, allies might be unwilling to invest in defense to the extent that they do not perceive a compelling external threat to themselves or elect to buck-pass in the hope that their neighbors will bear the costs of deterring or fighting potential regional hegemons.37Randall L. Schweller, Unanswered Threats: Political Constraints on the Balance of Power (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2006); William C. Wohlforth et al., “Testing Balance-of-Power Theory in World History,” European Journal of International Relations 13, no. 2 (2007): 155–85. Second, allies might be unable to balance an aspiring regional hegemon to the extent that it can overpower them even if they invest in defense and act collectively.

Buck-passing, balancing, and bandwagoning

Restrainers tend to advocate that U.S. allies work together to balance against local threats rather than buck-passing to the United States.

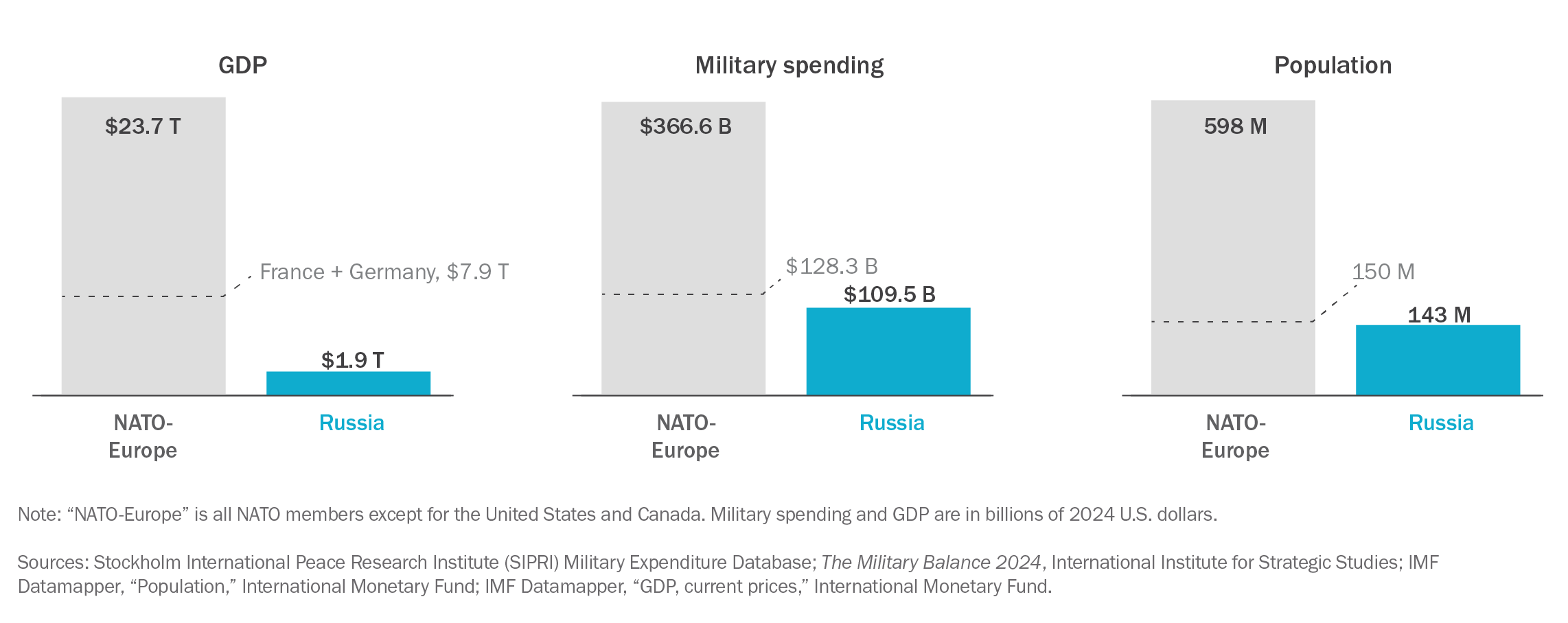

The extent to which either condition holds likely varies by region. It is far from clear whether any conceivable adversary has the capacity to achieve hegemony in key regions, particularly in Europe. European NATO members dwarf Russia in the size of their economies and populations, and Russia has struggled to invade Ukraine despite its size advantages. This makes further expansion attempts unlikely in the short term, and even in the long term its capacity to sweep across the continent is limited given sufficient European efforts.

Chinese regional hegemony in Asia, in turn, is also unlikely, though not necessarily impossible. China is surrounded by capable neighbors, including Japan, India, and South Korea, as well as geographic barriers to conquest in the form of mountains and ocean. Nevertheless, while likely weaker than them collectively, it is stronger than its neighbors individually, and differing threat perceptions across regional states make forming a balancing coalition more difficult.38Elbridge A. Colby, The Strategy of Denial: American Defense in an Age of Great Power Conflict (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2021); David C. Kang, “Still Getting Asia Wrong: No ‘Contain China’ Coalition Exists,” Washington Quarterly 45, no. 4 (October 2, 2022): 79–98, https://doi.org/10.1080/0163660X.2022.2148918; Kelly A. Grieco and Jennifer Kavanagh, “The Elusive Indo-Pacific Coalition: Why Geography Matters,” Washington Quarterly 47, no. 1 (January 2, 2024): 103–21, https://doi.org/10.1080/0163660X.2024.2326324. But those perceptions would almost surely change if China began engaging in serial conquest, and the same features of the region’s geography that make balancing less likely—vast distances coupled with the difficulty of projecting power over water—also make rapid Chinese conquest more difficult.

In both regions, but especially in Europe, the greater threat is of limited conquest rather than regional hegemony. Waging a defensive war that keeps Russia from advancing into Central Europe may not require vast increases in European defense capabilities beyond what is currently on offer.39Barry R. Posen, “Europe Can Defend Itself,” Survival 62, no. 6 (November 1, 2020): 7–34, https://doi.org/10.1080/00396338.2020.1851080. In a large multilateral alliance like NATO, however, different threat perceptions in Western versus Eastern Europe raise questions about Western Europe’s willingness to invest in sufficient military power and act collectively to defend NATO’s most vulnerable members—particularly the Baltic countries of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania.40Hugo Meijer and Stephen G. Brooks, “Illusions of Autonomy: Why Europe Cannot Provide for Its Security if the United States Pulls Back,” International Security 45, no. 4 (April 20, 2021): 7–43, https://doi.org/10.1162/isec_a_00405; Rafał Ulatowski, “The Illusion of Germany’s Zeitenwende,” The Washington Quarterly 47, no. 3 (July 2, 2024): 59–76. This, in turn, raises questions about the ultimate credibility of NATO’s Article 5 if the United States attempts to pass more of the defense burden onto European members of the alliance.41Blankenship, “Managing the Dilemmas of Alliance Burden Sharing.” In Asia, the comparable scenario would be a Chinese attempt to seize Taiwan or impose a fait accompli over maritime claims in the East and South China Seas. Scholars and practitioners debate both the difficulties and merits of U.S. intervention in all of these cases, and it is beyond this paper’s purpose to resolve those debates.42David A. Shlapak and Michael W. Johnson, “Reinforcing Deterrence on NATO’s Eastern Flank: Wargaming the Defense of the Baltics,” RAND Corporation, 2016; Michael Hunzeker and Alexander Lanoszka, “A Question of Time: Enhancing Taiwan’s Conventional Deterrence Posture,” Center for Security Policy Studies, Schar School of Policy and Government, George Mason University, November 2018, https://csps.gmu.edu/publications/a-question-of-time/; Alexander Lanoszka and Michael A. Hunzeker, “Conventional Deterrence and Landpower in Northeastern Europe,” Army War College, Strategic Studies Institute, March 2019; Brendan Rittenhouse Green and Caitlin Talmadge, “Then What? Assessing the Military Implications of Chinese Control of Taiwan,” International Security 47, no. 1 (July 1, 2022): 7–45, https://doi.org/10.1162/isec_a_00437; Rachel Metz and Erik Sand, “Defending Taiwan: But … What Are the Costs?,” Washington Quarterly 46, no. 4 (October 2, 2023): 65–81, https://doi.org/10.1080/0163660X.2023.2285165; Jonathan D. Caverley, “The Taiwan Fallacy,” Foreign Affairs, August 7, 2024, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/taiwan/taiwan-fallacy.

NATO-Europe vs. Russia

U.S. retrenchment is unlikely to cause serious problems in Europe where European nations are more than capable of balancing against Russia.

The risks of success

The second potential risk is not that efforts to encourage burden-sharing will fail and risk adversary expansion, but rather that such efforts will succeed and reduce the United States’ ability to influence allies’ behavior. The United States has in some cases attempted to leverage partners’ security dependence to secure a variety of policy concessions, including maintaining relatively open markets to U.S. goods and services and participating in U.S. sanctions regimes.43Michael Mastanduno, Economic Containment: CoCom and the Politics of East-West Trade, Economic Containment (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1992); Michael Mastanduno, “System Maker and Privilege Taker: U.S. Power and the International Political Economy,” World Politics 61, no. 1 (2009): 121–54; Carla Norrlof, America’s Global Advantage: US Hegemony and International Cooperation (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010). To the extent that allies no longer receive U.S. protection—or have no need for it—the United States has fewer channels with which to shape allies’ behavior.44Blankenship, The Burden-Sharing Dilemma.

The degree to which alliances allow the United States to exert influence over allies has been the subject of substantial debate among scholars.45Norrlof, America’s Global Advantage; Stephen G. Brooks, G. John Ikenberry, and William C. Wohlforth, “Don’t Come Home, America: The Case against Retrenchment,” International Security 37, no. 3 (2012): 7–51; Daniel W. Drezner, “Military Primacy Doesn’t Pay (Nearly As Much As You Think),” International Security 38, no. 1 (2013): 52–79. It is likely that in some cases, security guarantees offer the United States leverage that allows it to ask favors of its partners. But this is true only if it chooses to exercise that leverage; unwillingness to do so undermines the influence alliances might otherwise offer. Also, to the extent the United States pursues more modest aims, as proponents of grand strategies of restraint or offshore balancing advocate, there are fewer issues over which the United States needs influence.46Posen, Restraint; Christopher Layne, “From Preponderance to Offshore Balancing: America’s Future Grand Strategy,” International Security 22, no. 1 (1997): 86–124. For example, the United States often relies on allies to host its military forces and participate in its foreign military operations, as in Iraq and Afghanistan.47J. Andrés Gannon and Daniel Kent, “Keeping Your Friends Close, but Acquaintances Closer: Why Weakly Allied States Make Committed Coalition Partners,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 65, no. 5 (2021): 889–918; Blankenship, “The Price of Protection”; Renanah Miles Joyce and Brian Blankenship, “The Market for Foreign Bases,” Security Studies 33, no. 2 (2024): 194–223, https://doi.org/10.1080/09636412.2023.2271387. But with less ambitious policy objectives, its need for such leverage would decline.

Moreover, there are three factors that likely mitigate the amount of influence loss from burden-sharing. The first is the threat environment. When allies are receptive to U.S. burden-sharing pressure because they perceive a high level of threat, their need for external support is likely to remain high, giving the United States future opportunities for influence should it elect to use them.48Glenn Snyder, Alliance Politics (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1997). The second is interest alignment. The United States does not need to exercise influence if allies are already likely to act in accordance with its preferences.

Third, to the extent that interests do not align, Washington has other sources of leverage in key issue areas, including trade and other aspects of economic policy. Among the most notable is the size of the U.S. economy, which constitutes the largest market in the world for partners looking to export. The size and diversity of the U.S. economy makes access to its market an attractive bargaining chip—though, as with alliances, one that the United States must have a credible threat of withholding to effectively wield.49Norrlof, America’s Global Advantage; Carla Norrlof et al., “Global Monetary Order and the Liberal Order Debate,” International Studies Perspectives 21, no. 2 (May 1, 2020): 109–53, https://doi.org/10.1093/isp/ekaa001; Eswar Prasad, “Top Dollar: Why the Dominance of America’s Currency Is Harder than Ever to Overturn,” Foreign Affairs 103, no. 4 (2024): 103–13. It also affords the United States the luxury of being less dependent on foreign trade.50Albert O. Hirschman, National Power and the Structure of Foreign Trade (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1945); Chad Rector, Federations: The Political Dynamics of Cooperation (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2009), 20–21.

The nuclear dimension

Finally, in a scenario where allies assume more of the conventional defense burden, there may be questions about the sustainability of the U.S. nuclear umbrella. The United States has historically used its alliances to limit the spread of nuclear weapons, both by reducing allies’ need to acquire them and by wielding threats to abandon allies if they pursued them.51Eugene Gerzhoy, “Alliance Coercion and Nuclear Restraint: How the United States Thwarted West Germany’s Nuclear Ambitions,” International Security 39, no. 4 (2015): 91–129; Nuno P. Monteiro and Alexandre Debs, Nuclear Politics: The Strategic Causes of Proliferation (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2017); Alexander Lanoszka, Atomic Assurance: The Alliance Politics of Nuclear Proliferation (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2018); Nicholas Miller, Stopping the Bomb: The Sources and Effectiveness of U.S. Nonproliferation Policy (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2018).

If allies are asked to shoulder most if not all of the conventional burden for defending themselves and become more capable of doing so, they may question the credibility of U.S. nuclear guarantees. At the same time, the United States may question the wisdom of threatening nuclear war when it has less influence over the use of conventional force.52Mike Sweeney, “How Would Europe Defend Itself?,” Defense Priorities, April 11, 2023, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/how-would-europe-defend-itself/.

But it is not necessarily inevitable that shifting more of the defense burden onto allies would cause a nuclear proliferation cascade. Total withdrawal that includes folding the U.S. nuclear umbrella would increase the risk of proliferation the most. But even in this scenario, allies would still face many hurdles to proliferation—most notably the risks of sanctions and preventive attack.53Etel Solingen, Nuclear Logics: Contrasting Paths in East Asia and the Middle East (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007); Monteiro and Debs, Nuclear Politics; Miller, Stopping the Bomb; Jeffrey M. Kaplow, Signing Away the Bomb: The Surprising Success of the Nuclear Nonproliferation Regime (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2022).

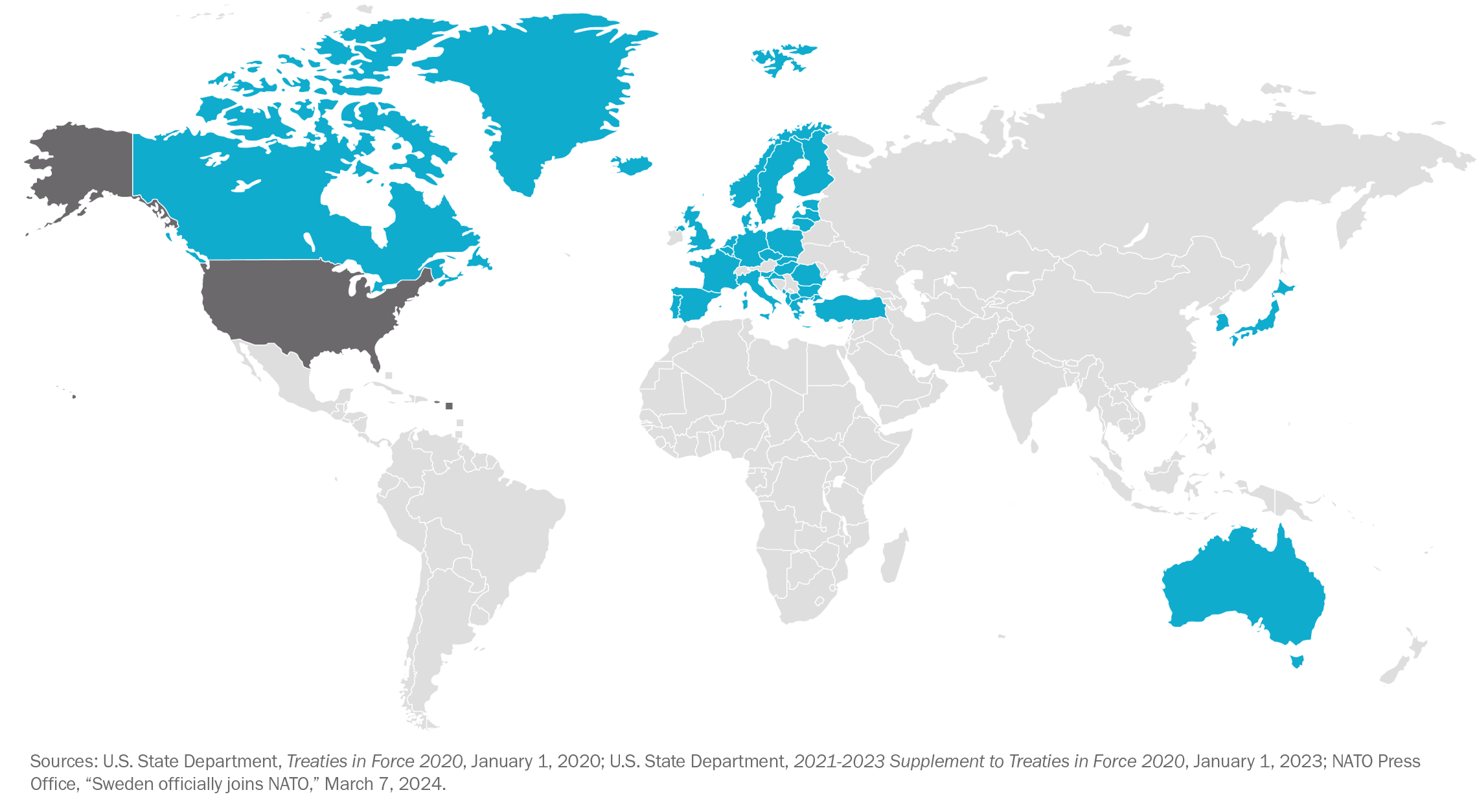

The U.S. nuclear umbrella

Around 30 countries are considered to be under the U.S. nuclear umbrella.

Especially in NATO, it is at least conceivable that the British and French arsenals could serve as a partial, temporary backstop. France has historically declined to participate in NATO nuclear planning, part of a broader position of NATO skepticism that included withdrawal from the alliance’s military command from 1966–2009.54Sweeney, “How Would Europe Defend Itself?,” 23–24. That position is not necessarily permanent and may change in the event of a U.S. withdrawal. Despite initially championing the pursuit of a negotiated settlement with Russia over Ukraine, for example, French President Emmanuel Macron took a more hawkish tone as continued U.S. military assistance came into doubt, suggesting in 2024 that deploying NATO troops to Ukraine should not be ruled out.55Hugh Schofield, “Macron Switches from Dove to Hawk on Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine,” BBC, March 16, 2024, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-68575251; Leila Abboud, Christopher Miller, and Henry Foy, “France Leads Initiative on Sending Military Trainers to Ukraine,” Financial Times, May 30, 2024, https://www.ft.com/content/37ed6927-c1e2-4ed3-be2a-871e03fd9ebb.

Living with burden-sharing’s risks?

U.S. resources are scarce, and attempts to maintain presences in Europe, East Asia, and the Middle East have spread them thinly. Deployments of air and naval assets in the Mediterranean in the wake of ongoing conflicts in Europe and the Middle East have periodically left the United States without a carrier presence in the Western Pacific.56Ryan Chan, “U.S. Faces Sea Power Gap in China’s Backyard as Carriers Leave Asia,” Newsweek, July 4, 2024, https://www.newsweek.com/us-navy-aircraft-carrier-gap-china-western-pacific-1920996; Ken Moriyasu, “U.S. Sends Another Carrier from Asia to Middle East, Widening Pacific Gap,” Nikkei Asia, August 7, 2024, https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/International-relations/Indo-Pacific/U.S.-sends-another-carrier-from-Asia-to-Middle-East-widening-Pacific-gap. More broadly, the United States faces munitions shortfalls for assets useful in all three regions.57Seth G. Jones, “Empty Bins in a Wartime Environment: The Challenge to the U.S. Defense Industrial Base,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, January 23, 2023, https://www.csis.org/analysis/empty-bins-wartime-environment-challenge-us-defense-industrial-base; Kathryn Levantovscaia, “Overstretched and Undersupplied: Can the US Afford Its Global Security Blanket?,” Atlantic Council (blog), January 5, 2024, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/overstretched-and-undersupplied-can-the-us-afford-its-global-security-blanket/.

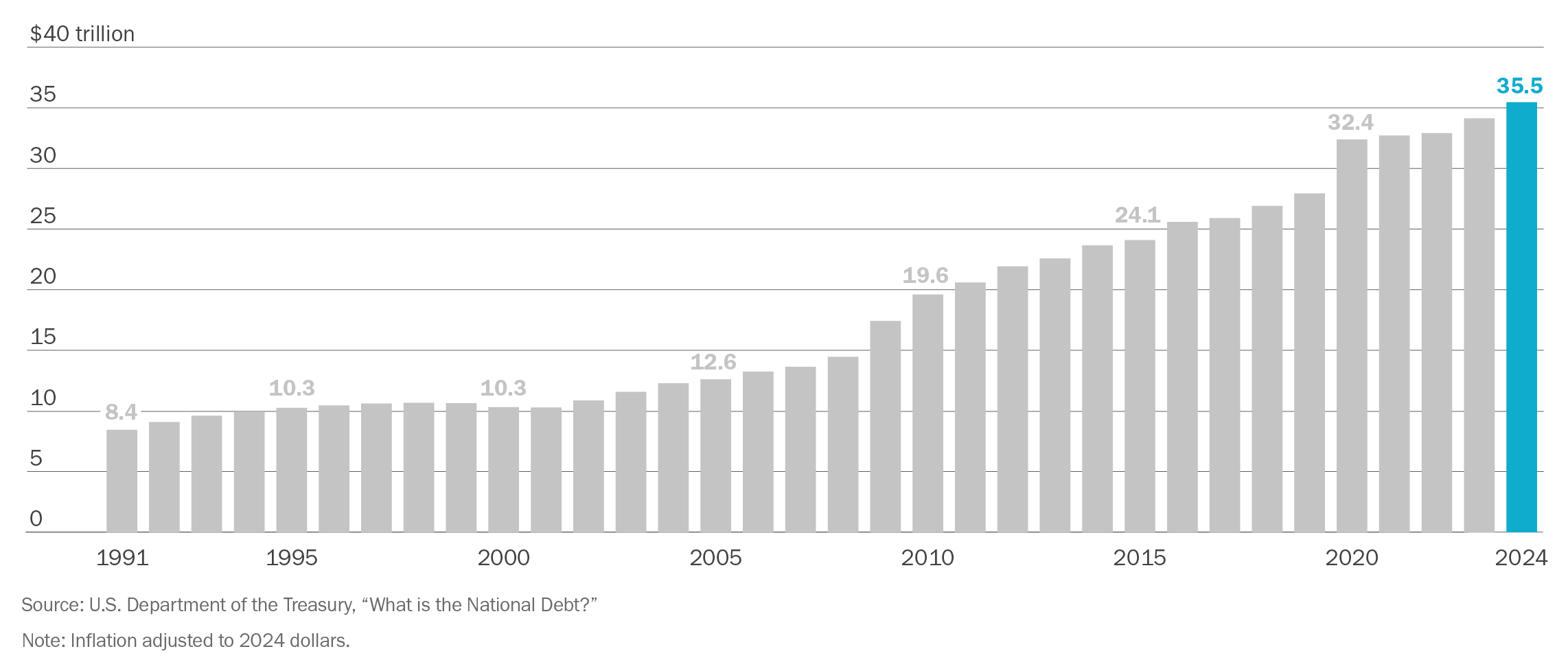

Beyond deploying existing capabilities, the United States also faces constraints on its capacity to procure future capabilities. Competing domestic priorities make raising revenue or cutting non-discretionary spending difficult. When budget cuts do occur, they tend to fall hardest on discretionary spending, including defense, as in the case of sequestration during the early 2010s. Otherwise, the United States runs substantial budget deficits, and has accumulated a debt burden that surpasses 120 percent of its GDP and continues to rise.58U.S. Department of the Treasury, “What Is the National Debt?,” FiscalData, accessed August 12, 2024, https://fiscaldata.treasury.gov/americas-finance-guide/national-debt/.

The United States’ ability to keep spending this way is an open question amidst concerns about inflation, which can be exacerbated by deficit spending, and higher interest rates, which make debt more expensive. Even when funds are available, production constraints in the U.S. defense industrial base limit the speed with which assets and munitions can be produced.59Steve Cohen, “Almost All Navy Shipbuilding Is Hopelessly behind Schedule,” Hill, May 2, 2024, https://thehill.com/opinion/national-security/4624326-almost-all-navy-shipbuilding-is-hopelessly-behind-schedule-as-war-looms/; Megan Eckstein, “US Navy Ship Programs Face Years-Long Delays amid Labor, Supply Woes,” Defense News, April 2, 2024, https://www.defensenews.com/naval/2024/04/02/us-navy-ship-programs-face-years-long-delays-amid-labor-supply-woes/.

U.S. sovereign debt since the Cold War

The United States’ sovereign debt stood at about $35.5 trillion in 2024 or about 123 percent of GDP, a stark increase since the end of the Cold War.

If it is serious about burden-sharing, the United States will need to cope with its risks when they cannot be avoided. Relying on Europe to assume the lead in NATO to compensate for a substantially diminished U.S. role, for example, raises questions about the defense of the alliance’s Eastern Flank.60Ben Barry et al., “Defending Europe: Scenario-Based Capability Requirements for NATO’s European Members,” Institute for Strategic Studies, April 2019, https://www.iiss.org/research-paper//2019/05/defending-europe; Posen, “Europe Can Defend Itself.” The United States may be able to shape its allies’ arming decisions, but its ability to do so is constrained by its allies’ threat perceptions. Ultimately, if Western Europe is not willing and able to defend Eastern European NATO members, which are far closer to them than they are to the United States, it is not clear how sustainable NATO’s security guarantee will ever be if the United States has any intention to prioritize its scarce resources.

Similarly, in some cases, the United States may simply need to learn to live with less deferential allies that are more capable of acting alone. Historically, U.S. policymakers have been willing to sacrifice some burden-sharing in the hopes of maintaining influence. But this preference is not a given.61Blankenship, The Burden-Sharing Dilemma, 140. Ultimately, the value of lost influence is largely in the eye of the beholder. Those with a more expansive view of U.S. global interests and what the United States should want from its alliances are less likely to favor encouraging allies to develop enough capability to become independent than those who take a more limited view of what alliances are for. For advocates of burden-shifting and a grand strategy of restraint, greater autonomy among U.S. allies is a feature, not a bug.

The issue of nuclear proliferation is perhaps the most difficult and sensitive. A strict division of labor where the United States provides a nuclear umbrella but offers little-to-no promise of conventional assistance while allies supply the conventional forces but have no access to nuclear weapons may be sustainable at least for a time. Particularly in Europe, NATO may be able to lean on the French and British arsenals, provided they are willing to employ them for extended deterrence.

If not, however, there are few obvious solutions. One might be nuclear sharing. But short of giving nuclear weapons to allies outright, this would in turn continue to implicate the United States in the defense of allies, but with less control over outcomes than it has now or than it would even in a scenario where U.S. conventional forces withdraw but the nuclear umbrella remains intact.62Joshua Byun and Do Young Lee, “The Case Against Nuclear Sharing in East Asia,” Washington Quarterly 44, no. 4 (October 2, 2021): 67–87, https://doi.org/10.1080/0163660X.2021.2018793.

The other is to accept some amount of proliferation, as has been advocated by some scholars and practitioners.63Kenneth N. Waltz, “The Spread of Nuclear Weapons: More May Be Better,” Adelphi Papers 171 (1981); John J. Mearsheimer, “The Case for a Ukrainian Nuclear Deterrent,” Foreign Affairs 72, no. 3 (1993): 50–66, https://doi.org/10.2307/20045622; Denny Roy, “Elbridge Colby Is Wrong on the U.S.-ROK Alliance,” National Interest, May 23, 2024, https://nationalinterest.org/blog/korea-watch/elbridge-colby-wrong-us-rok-alliance-211153. This has some historical precedent. Most notably, the Eisenhower administration hoped that selective proliferation might offer the United States an opportunity to retrench from Europe. But the Soviet reaction—culminating in the Berlin Crises of 1958 and 1961—ultimately led the United States to embrace nonproliferation.64Marc Trachtenberg, A Constructed Peace: The Making of the European Settlement, 1945-1963 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1999). If selective proliferation is the route that American policymakers choose, they will need to be prepared for the possibility that adversaries will do everything they can to prevent proliferation by U.S. allies around their borders—including perhaps Germany, Poland, South Korea, and Japan.65Byun, “Stuck Onshore.”

The preceding discussion has implications for how the United States might approach burden-sharing in Europe and East Asia, two regions with a high concentration of treaty allies and which are home to Russia and China. Of the two regions, retrenchment poses fewer dilemmas for the United States in Europe, where conditionality is also less likely to be effective than in Asia.

In the short term, U.S. drawdowns are unlikely to trigger Russian expansionism into NATO countries given its ongoing invasion of Ukraine. In the long term, Europe has far greater capacity to balance Russia alone than China’s neighbors do. Similarly, given NATO geography, U.S. attempts at conditionality are likely to be far less effective in motivating burden-sharing beyond Eastern Europe, where perceptions of threat from Russia are far higher.66Meijer and Brooks, “Illusions of Autonomy”; Blankenship, “Managing the Dilemmas of Alliance Burden Sharing.” Germany’s vaunted post-Ukraine foreign policy turning point (Zeitenwende) has disappointed in large part due to a lack of perceived urgency.67Benjamin Tallis, “The End of the Zeitenwende,” German Council on Foreign Relations, August 30, 2024, https://dgap.org/en/research/publications/end-zeitenwende; Ulatowski, “The Illusion of Germany’s Zeitenwende.”

But there is no silver bullet for soliciting burden-sharing. The effectiveness of both approaches depends heavily on the external threat environment. In difficult cases, even retrenchment is likely to fail. Conditionality may work just as well as retrenchment in comparatively easier cases and may be more attractive to risk-averse policymakers unwilling to drastically alter the status quo. Nevertheless, conditionality offers temporary solutions that must be continually renegotiated, and its effects may wane with use.

Ultimately, preferences for retrenchment or conditionality are likely to depend on far more than their effects on burden-sharing. Observers disagree in their level of risk tolerance, which risks they view as more salient, and about the value of alliances and need for burden-sharing in the first place. This paper’s goal is not to settle these disputes, but rather to inform them.

Endnotes

- 1Brian Blankenship, “Managing the Dilemmas of Alliance Burden Sharing,” Washington Quarterly 47, no. 1 (2024): 41–61, https://doi.org/10.1080/0163660X.2024.2323898.

- 2Michael Birnbaum, “Gates Rebukes European Allies in Farewell Speech,” Washington Post, June 10, 2011, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/gates-rebukes-european-allies-in-farewell-speech/2011/06/10/AG9tKeOH_story.html.

- 3Keren Yarhi-Milo, Knowing the Adversary: Leaders, Intelligence, and Assessment of Intentions in International Relations (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2014).

- 4Brian Blankenship, The Burden-Sharing Dilemma: Coercive Diplomacy in US Alliance Politics (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2023).

- 5Mancur Olson Jr. and Richard Zeckhauser, “An Economic Theory of Alliances,” Review of Economics and Statistics 48, no. 3 (1966): 266–79; John J. Mearsheimer, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics (New York: W.W. Norton, 2001).

- 6David A. Lake, Entangling Relations: American Foreign Policy in Its Century (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1999); David A. Lake, Hierarchy in International Relations (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2009); Brian Blankenship, “The Price of Protection: Explaining Success and Failure of US Alliance Burden-Sharing Pressure,” Security Studies 30, no. 5 (2021): 691–724.

- 7Mira Rapp-Hooper, “Saving America’s Alliances: The United States Still Needs the System That Put It on Top,” Foreign Affairs 99, no. 2 (2020): 127–40.

- 8Alex Velez-Green and Robert Peters, “The Prioritization Imperative: A Strategy to Defend America’s Interests in a More Dangerous World,” Heritage Foundation, August 1, 2024, https://www.heritage.org/defense/report/the-prioritization-imperative-strategy-defend-americas-interests-more-dangerous.

- 9Barry R. Posen, Restraint: A New Foundation for U.S. Grand Strategy (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2014).

- 10Rajan Menon, “Reconfiguring NATO: The Case for Burden Shifting,” Defense Priorities, May 2, 2024, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/reconfiguring-nato/; Benjamin Friedman, “A New NATO Agenda: Less U.S., Less Dependency,” Defense Priorities, July 8, 2024, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/a-new-nato-agenda/.

- 11Jordan Becker et al., “Transatlantic Shakedown: Presidential Shaming and NATO Burden Sharing,” Journal of Conflict Resolution, April 21, 2023, 00220027231167840, https://doi.org/10.1177/00220027231167840; Jordan Becker, “Pledge and Forget? Testing the Effects of NATO’s Wales Pledge on Defense Investment,” International Studies Perspectives, January 23, 2024, ekad027, https://doi.org/10.1093/isp/ekad027; Brian Blankenship, “Do Threats or Shaming Increase Public Support for Policy Concessions? Alliance Coercion and Burden-Sharing in NATO,” International Studies Quarterly 68, no. 2 (2024): sqae015.

- 12Richard Nixon, “Informal Remarks in Guam With Newsmen,” American Presidency Project, July 25, 1969, https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/informal-remarks-guam-with-newsmen.

- 13Paul K. MacDonald and Joseph M. Parent, Twilight of the Titans: Great Power Decline and Retrenchment (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2018).

- 14Brandon K. Yoder, “Retrenchment as a Screening Mechanism: Power Shifts, Strategic Withdrawal, and Credible Signals,” American Journal of Political Science 63, no. 1 (2019): 130–45, https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12395.

- 15Posen, Restraint.

- 16Carla Martínez Machain and T. Clifton Morgan, “The Effect of US Troop Deployment on Host States’ Foreign Policy,” Armed Forces & Society 39, no. 1 (2013): 102–23; Lake, Hierarchy in International Relations; Matthew Digiuseppe and Paul Poast, “Arms versus Democratic Allies,” British Journal of Political Science 48, no. 4 (2018): 981–1003; Matthew DiGiuseppe and Patrick E. Shea, “Alliances, Signals of Support, and Military Effort,” European Journal of International Relations 27, no. 4 (2021): 1067–89.

- 17Blankenship, The Burden-Sharing Dilemma.

- 18Blankenship, “The Price of Protection.”

- 19Thomas Schelling, Arms and Influence (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1966).

- 20Songying Fang and Kristopher W. Ramsay, “Outside Options and Burden Sharing in Nonbinding Alliances,” Political Research Quarterly 63, no. 1 (2010): 188–202; Blankenship, The Burden-Sharing Dilemma.

- 21Report on a NATO Commanders Meeting, September 30, 1970, Foreign Relations of the United States, 1969–1976, vol. 41, document 48.

- 22Blankenship, The Burden-Sharing Dilemma, chapter 2.

- 23Blankenship, “The Price of Protection.”

- 24Blankenship, “Do Threats or Shaming Increase Public Support for Policy Concessions?”

- 25Joshua Byun, “Stuck Onshore: Why the United States Failed to Retrench from Europe during the Early Cold War,” Texas National Security Review 7, no. 4 (July 2, 2024), https://tnsr.org/2024/07/stuck-onshore-why-the-united-states-failed-to-retrench-from-europe-during-the-early-cold-war/.

- 26As Henry Kissinger put it: “The greater the pressures for troop withdrawals in the United States, the greater the disinclination of our allies to augment their military establishments lest they justify further American withdrawals.” Henry Kissinger, White House Years (Boston, MA: Little, Brown, and Company, 1979), 394.

- 27Peter Harris, Why America Can’t Retrench (And How It Might) (Polity, 2024); Christopher S. Chivvis et al., “Strategic Change in U.S. Foreign Policy,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, July 23, 2024, https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2024/07/strategic-change-us-foreign-policy.

- 28Blankenship, The Burden-Sharing Dilemma, 105–7.

- 29Brian Blankenship, “Promises under Pressure: Statements of Reassurance in US Alliances,” International Studies Quarterly 64, no. 4 (2020): 1017–30.

- 30“Remarks by President Biden on the 75th Anniversary of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization Alliance,” July 9, 2024, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2024/02/13/biden-trump-nato-unamerican/.

- 31Reid B. C. Pauly, “Damned If They Do, Damned If They Don’t: The Assurance Dilemma in International Coercion,” International Security 49, no. 1 (2024): 91–132, https://doi.org/10.1162/isec_a_00488.

- 32James D. Fearon, “Bargaining, Enforcement, and International Cooperation,” International Organization 52, no. 2 (1998): 269–305; Todd S. Sechser, “Goliath’s Curse: Coercive Threats and Asymmetric Power,” International Organization 64, no. 4 (2010): 627–60.

- 33Blankenship, The Burden-Sharing Dilemma.

- 34Blankenship, “The Price of Protection.”

- 35Blankenship, The Burden-Sharing Dilemma, 92–107.

- 36Paul C. Avey, Jonathan N. Markowitz, and Robert J. Reardon, “Do US Troop Withdrawals Cause Instability? Evidence from Two Exogenous Shocks on the Korean Peninsula,” Journal of Global Security Studies 3, no. 1 (January 1, 2018): 72–92, https://doi.org/10.1093/jogss/ogx020.

- 37Randall L. Schweller, Unanswered Threats: Political Constraints on the Balance of Power (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2006); William C. Wohlforth et al., “Testing Balance-of-Power Theory in World History,” European Journal of International Relations 13, no. 2 (2007): 155–85.

- 38Elbridge A. Colby, The Strategy of Denial: American Defense in an Age of Great Power Conflict (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2021); David C. Kang, “Still Getting Asia Wrong: No ‘Contain China’ Coalition Exists,” Washington Quarterly 45, no. 4 (October 2, 2022): 79–98, https://doi.org/10.1080/0163660X.2022.2148918; Kelly A. Grieco and Jennifer Kavanagh, “The Elusive Indo-Pacific Coalition: Why Geography Matters,” Washington Quarterly 47, no. 1 (January 2, 2024): 103–21, https://doi.org/10.1080/0163660X.2024.2326324.

- 39Barry R. Posen, “Europe Can Defend Itself,” Survival 62, no. 6 (November 1, 2020): 7–34, https://doi.org/10.1080/00396338.2020.1851080.

- 40Hugo Meijer and Stephen G. Brooks, “Illusions of Autonomy: Why Europe Cannot Provide for Its Security if the United States Pulls Back,” International Security 45, no. 4 (April 20, 2021): 7–43, https://doi.org/10.1162/isec_a_00405; Rafał Ulatowski, “The Illusion of Germany’s Zeitenwende,” The Washington Quarterly 47, no. 3 (July 2, 2024): 59–76.

- 41Blankenship, “Managing the Dilemmas of Alliance Burden Sharing.”

- 42David A. Shlapak and Michael W. Johnson, “Reinforcing Deterrence on NATO’s Eastern Flank: Wargaming the Defense of the Baltics,” RAND Corporation, 2016; Michael Hunzeker and Alexander Lanoszka, “A Question of Time: Enhancing Taiwan’s Conventional Deterrence Posture,” Center for Security Policy Studies, Schar School of Policy and Government, George Mason University, November 2018, https://csps.gmu.edu/publications/a-question-of-time/; Alexander Lanoszka and Michael A. Hunzeker, “Conventional Deterrence and Landpower in Northeastern Europe,” Army War College, Strategic Studies Institute, March 2019; Brendan Rittenhouse Green and Caitlin Talmadge, “Then What? Assessing the Military Implications of Chinese Control of Taiwan,” International Security 47, no. 1 (July 1, 2022): 7–45, https://doi.org/10.1162/isec_a_00437; Rachel Metz and Erik Sand, “Defending Taiwan: But … What Are the Costs?,” Washington Quarterly 46, no. 4 (October 2, 2023): 65–81, https://doi.org/10.1080/0163660X.2023.2285165; Jonathan D. Caverley, “The Taiwan Fallacy,” Foreign Affairs, August 7, 2024, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/taiwan/taiwan-fallacy.

- 43Michael Mastanduno, Economic Containment: CoCom and the Politics of East-West Trade, Economic Containment (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1992); Michael Mastanduno, “System Maker and Privilege Taker: U.S. Power and the International Political Economy,” World Politics 61, no. 1 (2009): 121–54; Carla Norrlof, America’s Global Advantage: US Hegemony and International Cooperation (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010).

- 44Blankenship, The Burden-Sharing Dilemma.

- 45Norrlof, America’s Global Advantage; Stephen G. Brooks, G. John Ikenberry, and William C. Wohlforth, “Don’t Come Home, America: The Case against Retrenchment,” International Security 37, no. 3 (2012): 7–51; Daniel W. Drezner, “Military Primacy Doesn’t Pay (Nearly As Much As You Think),” International Security 38, no. 1 (2013): 52–79.

- 46Posen, Restraint; Christopher Layne, “From Preponderance to Offshore Balancing: America’s Future Grand Strategy,” International Security 22, no. 1 (1997): 86–124.

- 47J. Andrés Gannon and Daniel Kent, “Keeping Your Friends Close, but Acquaintances Closer: Why Weakly Allied States Make Committed Coalition Partners,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 65, no. 5 (2021): 889–918; Blankenship, “The Price of Protection”; Renanah Miles Joyce and Brian Blankenship, “The Market for Foreign Bases,” Security Studies 33, no. 2 (2024): 194–223, https://doi.org/10.1080/09636412.2023.2271387.

- 48Glenn Snyder, Alliance Politics (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1997).

- 49Norrlof, America’s Global Advantage; Carla Norrlof et al., “Global Monetary Order and the Liberal Order Debate,” International Studies Perspectives 21, no. 2 (May 1, 2020): 109–53, https://doi.org/10.1093/isp/ekaa001; Eswar Prasad, “Top Dollar: Why the Dominance of America’s Currency Is Harder than Ever to Overturn,” Foreign Affairs 103, no. 4 (2024): 103–13.

- 50Albert O. Hirschman, National Power and the Structure of Foreign Trade (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1945); Chad Rector, Federations: The Political Dynamics of Cooperation (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2009), 20–21.

- 51Eugene Gerzhoy, “Alliance Coercion and Nuclear Restraint: How the United States Thwarted West Germany’s Nuclear Ambitions,” International Security 39, no. 4 (2015): 91–129; Nuno P. Monteiro and Alexandre Debs, Nuclear Politics: The Strategic Causes of Proliferation (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2017); Alexander Lanoszka, Atomic Assurance: The Alliance Politics of Nuclear Proliferation (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2018); Nicholas Miller, Stopping the Bomb: The Sources and Effectiveness of U.S. Nonproliferation Policy (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2018).

- 52Mike Sweeney, “How Would Europe Defend Itself?,” Defense Priorities, April 11, 2023, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/how-would-europe-defend-itself/.

- 53Etel Solingen, Nuclear Logics: Contrasting Paths in East Asia and the Middle East (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007); Monteiro and Debs, Nuclear Politics; Miller, Stopping the Bomb; Jeffrey M. Kaplow, Signing Away the Bomb: The Surprising Success of the Nuclear Nonproliferation Regime (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2022).

- 54Sweeney, “How Would Europe Defend Itself?,” 23–24.

- 55Hugh Schofield, “Macron Switches from Dove to Hawk on Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine,” BBC, March 16, 2024, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-68575251; Leila Abboud, Christopher Miller, and Henry Foy, “France Leads Initiative on Sending Military Trainers to Ukraine,” Financial Times, May 30, 2024, https://www.ft.com/content/37ed6927-c1e2-4ed3-be2a-871e03fd9ebb.

- 56Ryan Chan, “U.S. Faces Sea Power Gap in China’s Backyard as Carriers Leave Asia,” Newsweek, July 4, 2024, https://www.newsweek.com/us-navy-aircraft-carrier-gap-china-western-pacific-1920996; Ken Moriyasu, “U.S. Sends Another Carrier from Asia to Middle East, Widening Pacific Gap,” Nikkei Asia, August 7, 2024, https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/International-relations/Indo-Pacific/U.S.-sends-another-carrier-from-Asia-to-Middle-East-widening-Pacific-gap.

- 57Seth G. Jones, “Empty Bins in a Wartime Environment: The Challenge to the U.S. Defense Industrial Base,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, January 23, 2023, https://www.csis.org/analysis/empty-bins-wartime-environment-challenge-us-defense-industrial-base; Kathryn Levantovscaia, “Overstretched and Undersupplied: Can the US Afford Its Global Security Blanket?,” Atlantic Council (blog), January 5, 2024, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/overstretched-and-undersupplied-can-the-us-afford-its-global-security-blanket/.

- 58U.S. Department of the Treasury, “What Is the National Debt?,” FiscalData, accessed August 12, 2024, https://fiscaldata.treasury.gov/americas-finance-guide/national-debt/.

- 59Steve Cohen, “Almost All Navy Shipbuilding Is Hopelessly behind Schedule,” Hill, May 2, 2024, https://thehill.com/opinion/national-security/4624326-almost-all-navy-shipbuilding-is-hopelessly-behind-schedule-as-war-looms/; Megan Eckstein, “US Navy Ship Programs Face Years-Long Delays amid Labor, Supply Woes,” Defense News, April 2, 2024, https://www.defensenews.com/naval/2024/04/02/us-navy-ship-programs-face-years-long-delays-amid-labor-supply-woes/.

- 60Ben Barry et al., “Defending Europe: Scenario-Based Capability Requirements for NATO’s European Members,” Institute for Strategic Studies, April 2019, https://www.iiss.org/research-paper//2019/05/defending-europe; Posen, “Europe Can Defend Itself.”

- 61Blankenship, The Burden-Sharing Dilemma, 140.

- 62Joshua Byun and Do Young Lee, “The Case Against Nuclear Sharing in East Asia,” Washington Quarterly 44, no. 4 (October 2, 2021): 67–87, https://doi.org/10.1080/0163660X.2021.2018793.

- 63Kenneth N. Waltz, “The Spread of Nuclear Weapons: More May Be Better,” Adelphi Papers 171 (1981); John J. Mearsheimer, “The Case for a Ukrainian Nuclear Deterrent,” Foreign Affairs 72, no. 3 (1993): 50–66, https://doi.org/10.2307/20045622; Denny Roy, “Elbridge Colby Is Wrong on the U.S.-ROK Alliance,” National Interest, May 23, 2024, https://nationalinterest.org/blog/korea-watch/elbridge-colby-wrong-us-rok-alliance-211153.

- 64Marc Trachtenberg, A Constructed Peace: The Making of the European Settlement, 1945-1963 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1999).

- 65Byun, “Stuck Onshore.”

- 66Meijer and Brooks, “Illusions of Autonomy”; Blankenship, “Managing the Dilemmas of Alliance Burden Sharing.”

- 67Benjamin Tallis, “The End of the Zeitenwende,” German Council on Foreign Relations, August 30, 2024, https://dgap.org/en/research/publications/end-zeitenwende; Ulatowski, “The Illusion of Germany’s Zeitenwende.”

More on Eurasia

By Geoff LaMear

October 11, 2025

Featuring Daniel Davis

September 25, 2025

Featuring Daniel Davis

September 15, 2025

Events on Burden sharing