April 3, 2025

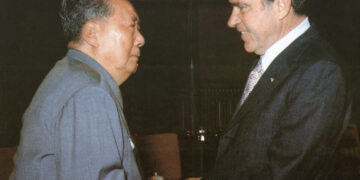

Kim Jong Un is Watching Trump’s Ukraine Diplomacy With Interest

From March 23 to 25, US officials facilitated indirect negotiations between Ukraine and Russia in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, in an attempt to cement a short-term ceasefire in a war that crossed its four-year mark in February. The latest round of shuttle diplomacy occurred two weeks after Washington and Kyiv agreed to a 30-day truce on land, air and sea. Ideally, the pause in hostilities would not only freeze the conflict on the ground but provide the parties with an opportunity to begin addressing the systemic issues—Russian President Vladimir Putin’s expansionist ambitions; NATO’s enlargement toward Russian borders; Ukraine’s long-term relationship to Western political and security institutions—that have perpetuated the fighting. The Russians’ response was ambivalent; while Putin claimed he was sympathetic to the truce, he slow-walked the entire process by questioning how it would be enforced, who would determine violations and how violators would be penalized. After President Donald Trump ended his March 18 call with Putin, the 30-day truce was downgraded to a 30-day cessation of attacks on energy and infrastructure targets. Washington’s efforts to extend the ceasefire to the Black Sea is running into another roadblock from Putin, who is insisting on concrete sanctions relief before any pause.

To the average reader, all of this might seem like the boring, monotonous procedures of a diplomatic process that may not even succeed in the end. Yet it is unlikely North Korean leader Kim Jong Un and his legion of experienced negotiators view it the same way. In fact, the opposite is likely the case—as the Trump administration engages with Putin and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, the Kim regime will be watching the machinations from the sidelines and studying what strategy and tactics are most effective in eliciting concessions from Trump; whether resistance over time will compel Washington to discard its maximalist negotiating positions; and how committed Trump really is to diplomacy. South Korea is doing much the same, albeit for different reasons—depending on how much the US concedes to the Russians, how much pressure the Ukrainians feel during the course of negotiations and how Trump responds in the event of a diplomatic breakdown, policymakers in Seoul will either worry about what this all means for their own security or be partly reassured when time comes for their own negotiations with the Trump administration.

Author

Daniel

DePetris

Fellow

More on Asia

By John Mueller

April 10, 2025

Featuring Jennifer Kavanagh

April 2, 2025

Featuring Lyle Goldstein

April 1, 2025

Featuring Jennifer Kavanagh

March 27, 2025

Featuring Jennifer Kavanagh

March 25, 2025