In-context: U.S. aid to Ukraine

Well into the third year of the war in Ukraine, the aid provided to Ukraine by the United States has become an increasingly contentious topic. This page clarifies where U.S. aid to Ukraine stands and provides context to ongoing debates by addressing some critical questions:

- How much aid has the U.S. given to Ukraine?

- What type of aid has the U.S. given to Ukraine?

- How does spending on Ukraine compare to other U.S. aid?

- How much have the Europeans contributed relative to the United States?

- What are the challenges to increasing the European share of military aid?

How much aid has the U.S. given to Ukraine?

Estimates of U.S. aid to Ukraine can vary depending on the timing of the report, the type of aid being discussed, and what type of spending is included. This section will look at two of the most commonly used figures for total U.S. aid to Ukraine. Both figures are correct, despite their large discrepancy, because they measure aid differently.

$105-107 billion: Estimates in this range, like those provided by the Kiel Institute or the Council on Foreign Relations, define aid as direct bilateral funds or equipment sent directly from the United States to Ukraine. This includes the costs of military equipment sent to Ukraine, assistance funds sent to the Ukrainian government, and funds spent on humanitarian efforts. As of April 2024, the Kiel Institute estimates have been updated to reflect aid allocations and deliverables, rather than just commitments, which allows for a better understanding of how much bilateral aid is actually getting to Ukraine. Total U.S. bilateral aid is still expected to increase as current commitments are formally allocated and delivered.

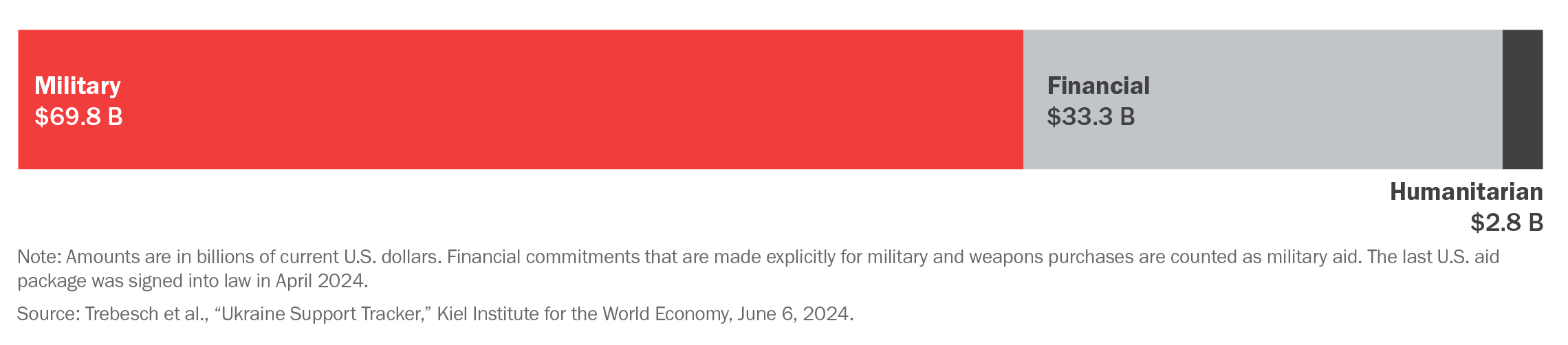

U.S. direct bilateral aid to Ukraine

Bilateral funds do not include money that is allocated as a response to the Ukraine war but does not go to Ukraine directly. The funds that are not directly delivered to Ukraine cover a number of related spending areas, including the costs of shifting military equipment and personnel in Europe, the bureaucratic logistics of aid planning and distributing, and the costs associated with planning and producing the necessary military equipment that aid will take from U.S. stockpiles. The small range in this figure is explained by differences in the criteria regarding what equipment or types of funds get included in the definition of direct bilateral. This aid figure strives to capture precisely the amount of direct aid, making it useful in cross-country comparisons though potentially limited in other respects.

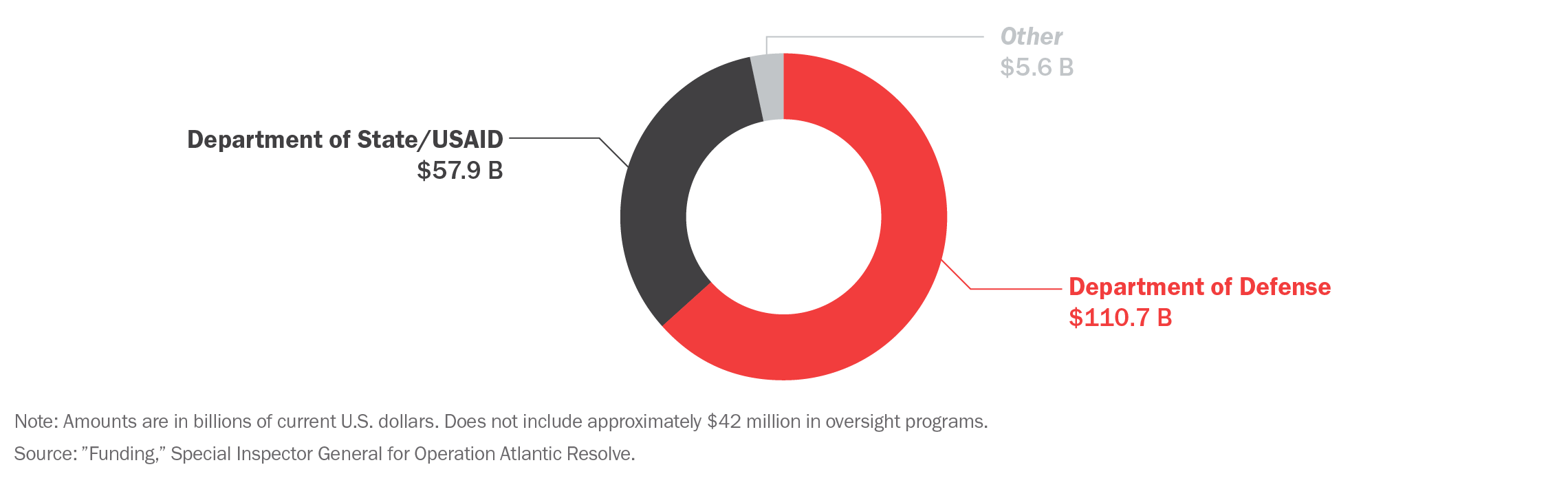

$113 billion: This figure encompasses all spending that the U.S. government has allocated in its efforts to aid Ukraine. It includes not only direct bilateral funds to support Ukraine, but also funds allocated to American partners, Ukraine-related U.S. defense operations in the region, and funds allocated domestically to related U.S. national security programs related to aiding Ukraine. It is an estimate that is specific to the United States and therefore difficult to compare across countries. Given the new bill passed in April 2024, total U.S. spending could reach about $175 billion, once the funds that are committed by the bill have been formally allocated.

Total funds allocated through Ukraine assistance supplemental spending, by department or agency

The $113 billion estimate provides a more precise understanding of how much the conflict in Ukraine has cost the United States in total. It includes logistics, bureaucratic costs, defense planning and posturing, and re-procurement programs geared towards replenishing U.S. weapons inventory. These costs tend to be used internally by the United States, as in this oversight plan from the Defense Department.

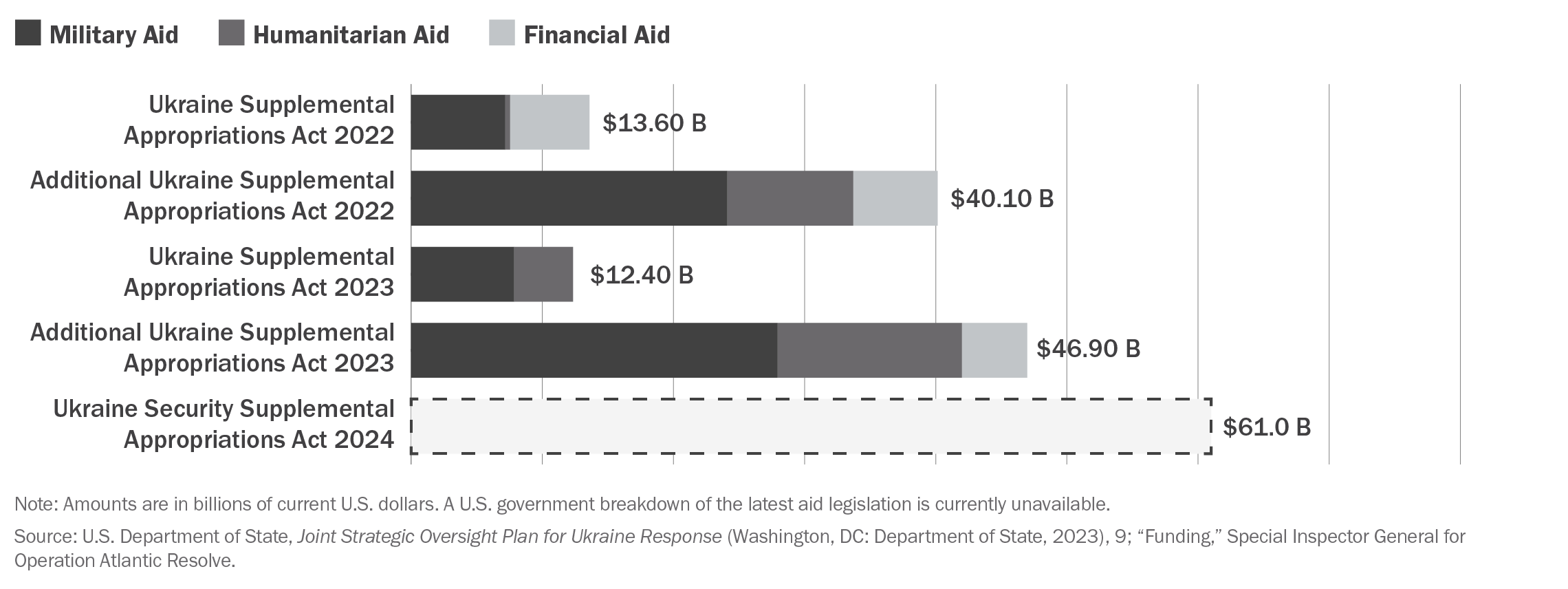

In the first two years of the war, Congress has passed four appropriations bills to fund U.S. aid to Ukraine: the Ukraine Supplemental Appropriation Act of 2022, the Additional Ukraine Supplemental Appropriations Act of 2022, the Ukraine Supplemental Appropriations Act of 2023, and the Additional Ukraine Supplemental Appropriations Act of 2023. Often, funds are initially authorized and allocated through presidential drawdown authority outside of congressional authority, but those funds are then backfilled by the bills passed specifically to address the situation. Presidential drawdowns are used to allocate funds that have already been committed in the aid packages.

Late in April 2024, a new bill totaling $61 billion in aid to Ukraine was passed by Congress and signed into law by President Biden. The Ukraine Security Supplemental Appropriations Act of 2024 provides $25.7 billion in military funding to replace equipment already sent or being sent to Ukraine, grants and loans through the State Department’s Foreign Military Financing (FMF) program, and funds to enhance the U.S. industrial base and its ability to produce the necessary military equipment. The bill also provides $17 billion in funding for the Ukraine Security Assistance Initiative (USAI) and U.S. intelligence operations, $7.9 billion in economic assistance to Ukraine, $7.3 billion to heighten U.S. force presence in Europe, $2.5 billion in humanitarian aid, and $335 million to the government agencies involved, including the Department of Energy’s nonproliferation activities. If all of the money provided for in this aid package is allocated, total U.S. spending could reach about $175 billion.

What type of aid has the U.S. given to Ukraine?

U.S. aid to Ukraine can be broken down into three main types: military, financial, and humanitarian.

Total U.S. aid by type and legislation

Military aid: Military aid is intended to address the needs of Ukraine’s military efforts against Russia. This includes weapons and foreign military financing, as well as support for NATO allies providing aid to Ukraine, U.S. weapons production, and replenishing U.S. and NATO allies’ weapons stocks.

Financial aid: Financial aid is monetary support to address the needs of Ukraine’s government and U.S. diplomacy in Ukraine. This includes funds for repairing embassies, staffing, legal support, direct budgetary support, and more.

Humanitarian aid: Humanitarian aid is intended to address the emergency needs of the Ukrainian people. This includes initiatives to support Ukraine’s agriculture industry, support for Ukraine’s democratic institutions, refugee assistance, urgent food assistance, health care, and more.

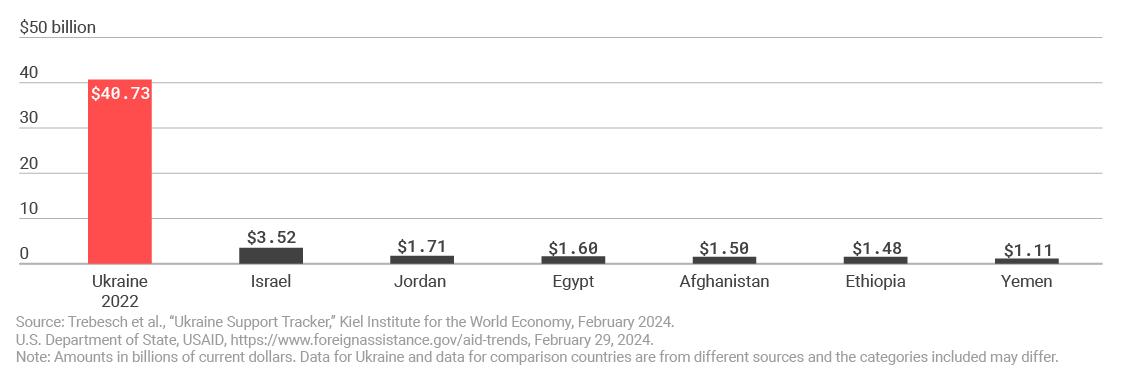

How does spending on Ukraine compare to other U.S. aid?

The chart below compares Ukraine aid in 2022 to the top recipients of aid in 2021. Looking at all types of aid, the $40 billion of direct bilateral aid sent to Ukraine in 2022 is a staggering amount compared to the top aid recipients in 2021.

U.S. aid to Ukraine in 2022 vs. top recipients in 2021

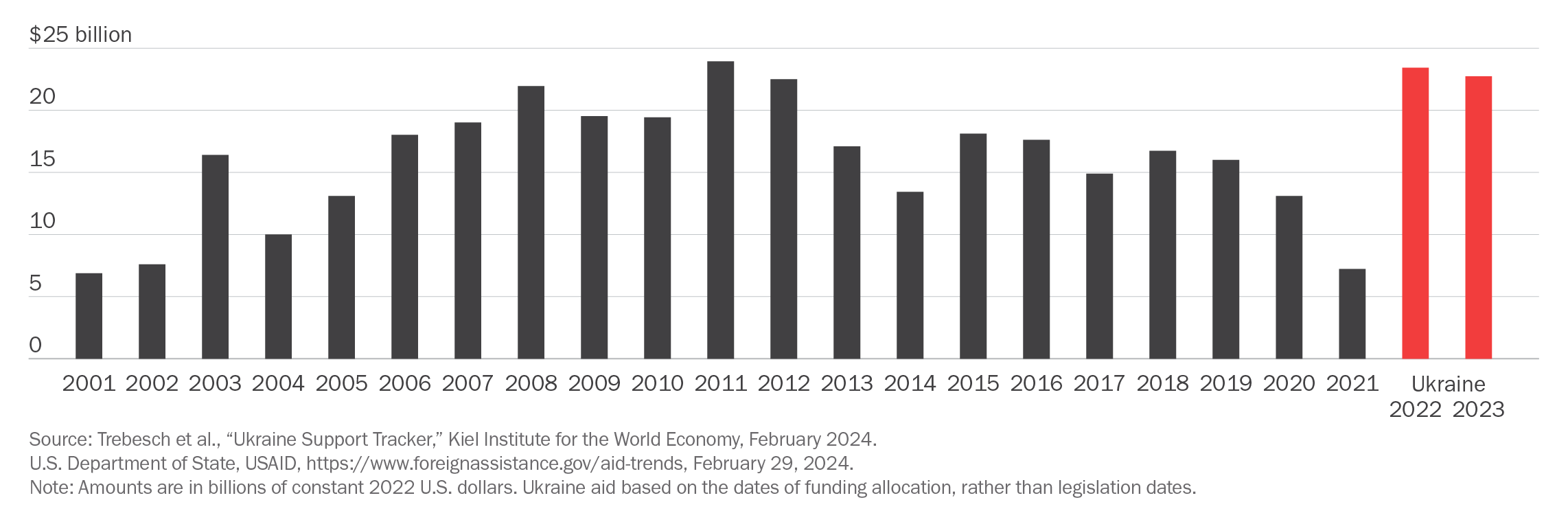

The United States has spent the most on military aid to Ukraine, as compared to other types of assistance. While that might seem inevitable given the major war there, the disparities are still striking. The bars marked in red on the graph below show security assistance just to Ukraine, while the gray bars represent annual U.S. security assistance to the entire globe. 2001-2021 were not quiet years in terms of security assistance either, as the United States was engaged in two extended overseas military interventions during much of that period, and several other military excursions as well. Yet in 2023, U.S. military aid to Ukraine amounted to more than U.S. yearly security assistance to the entire world in almost every year from 2001-2021.

Total U.S. security assistance obligations by year 2001-2021 vs. Ukraine 2022-2023

How much have the Europeans contributed relative to the United States?

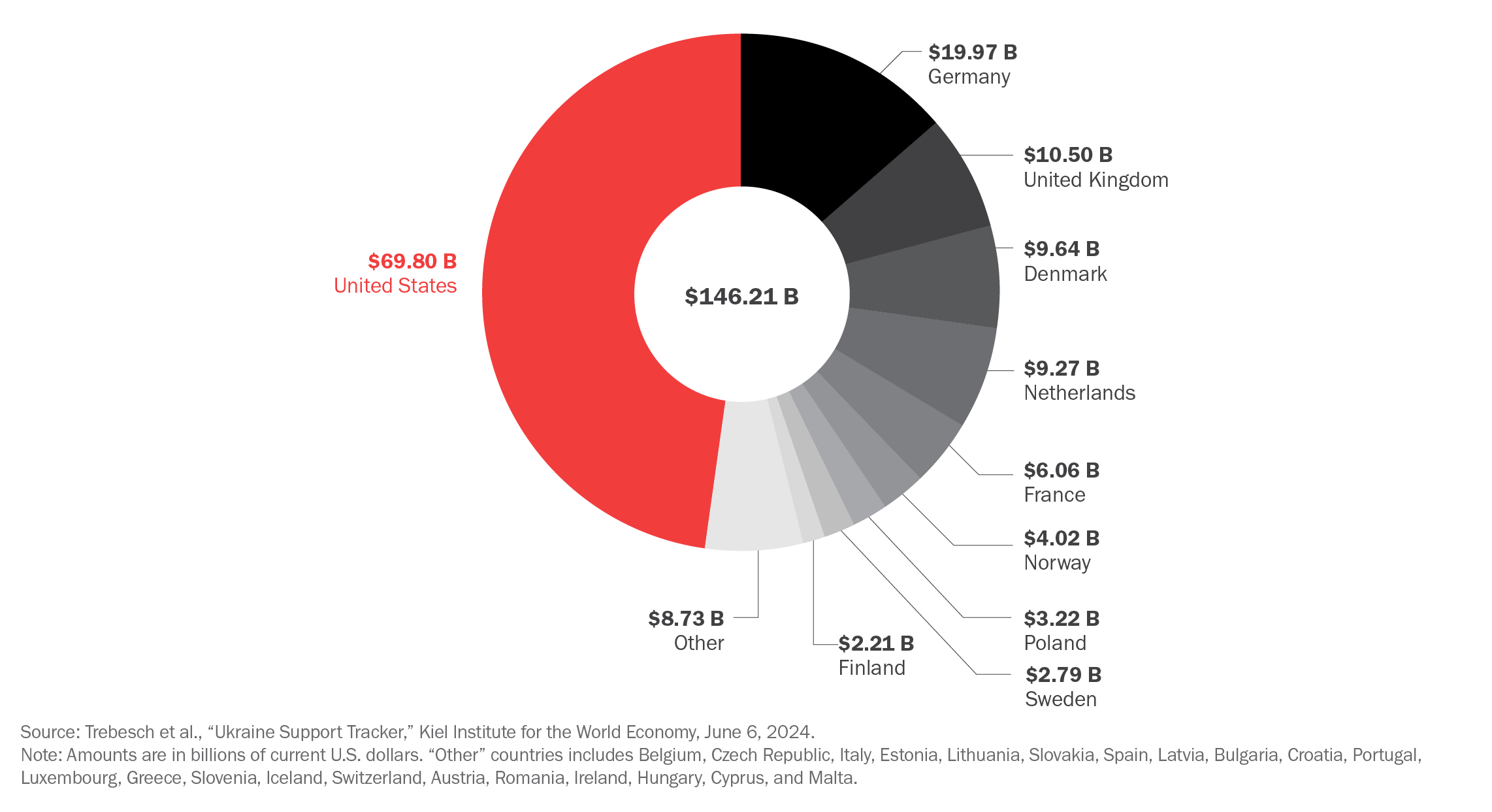

Total aid: United States vs. Europe

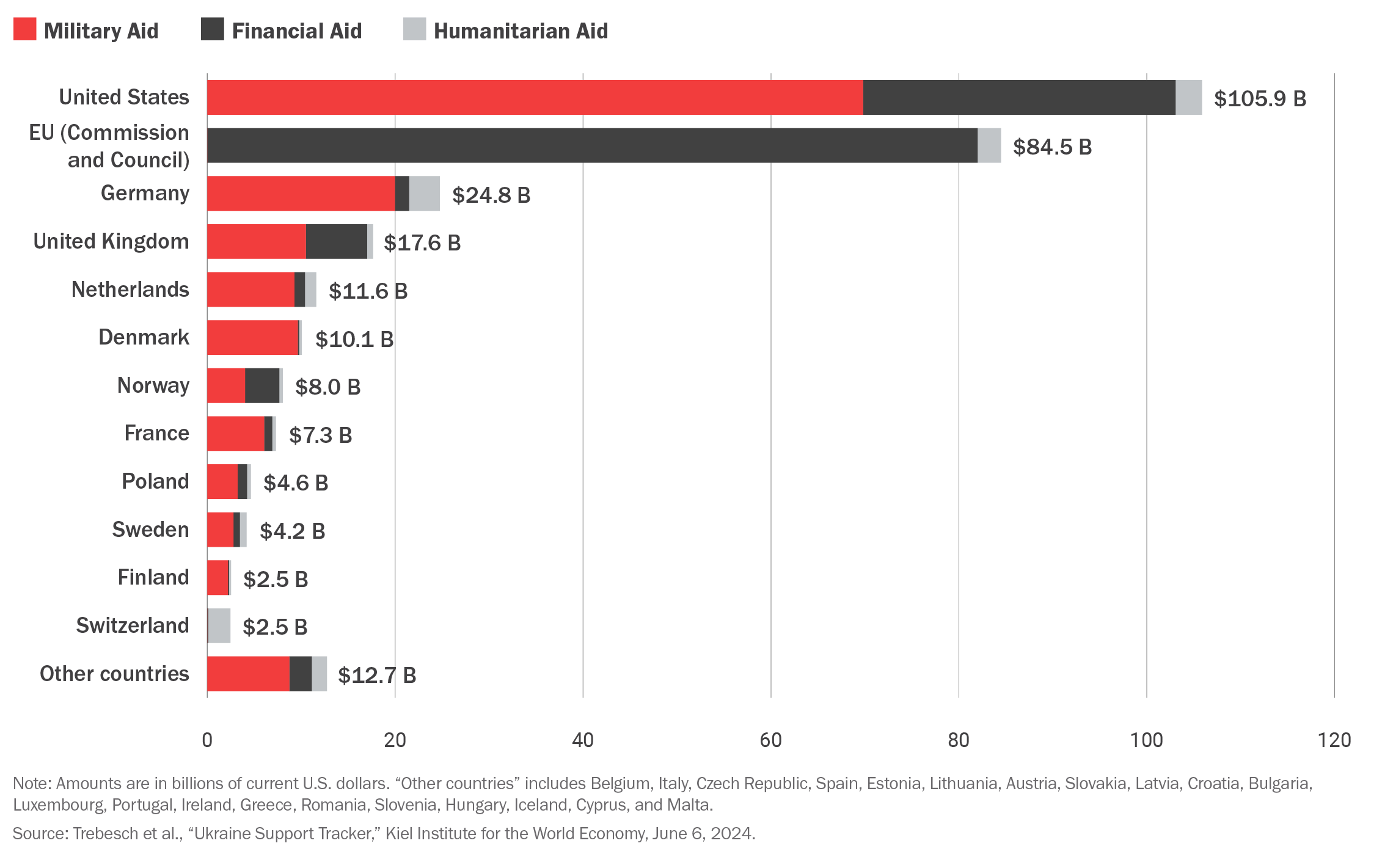

The United States sends nearly the same amount of military aid to Ukraine as all of Europe does. European military aid is given only bilaterally, with some countries able to offer more than others. This is due to several challenges facing even the largest European countries when it comes to their military stockpiles and weapons production.

U.S. vs. Europe, direct bilateral military aid

European nations have largely focused on financial and humanitarian aid, especially in aid flows through EU institutions. The United States thus accounts for almost 50 percent of military aid to Ukraine. In the graph below, the bilateral aid recorded from each European country does not include their additional contributions dispersed to Ukraine through EU institutions.

U.S. vs. European direct bilateral aid to Ukraine, by type

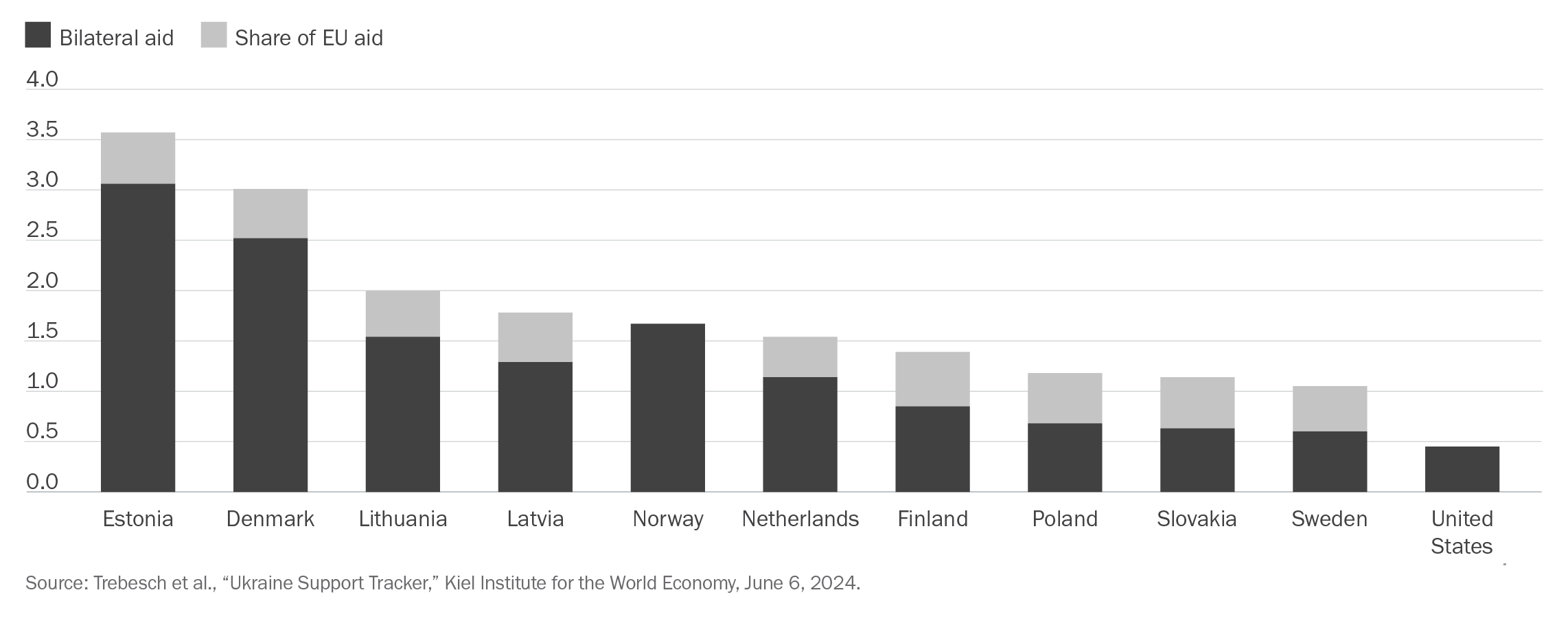

The Eastern European and Nordic countries have contributed the most relative to the size of their economies, which makes sense given their proximity to Russia. While their commitments might seem small relative to the amounts that much larger countries can contribute, relative to their GDPs they have committed to large aid burdens. The increased spending burden taken on by the countries most proximate to the conflict indicates that European countries can and will take on greater burdens when it’s central to their security interests to do so.

U.S. vs. European bilateral aid to Ukraine (by % of GDP)

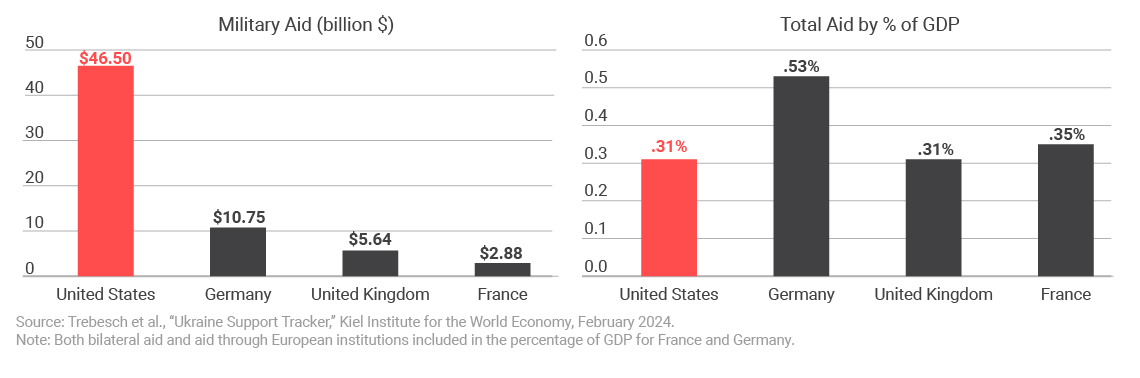

However, the question remains as to whether major U.S. allies in Europe, namely Germany, France, and the United Kingdom, are accepting adequate responsibility for the impacts of a war on their continent directly. This question has been debated in particular as it applies to the extensive needs of Ukraine for military assistance. Germany, being the closest of the three nations to Russia, faces the greatest pressure from a Russian security threat. While these countries are small by size and economy when compared to the United States, cumulatively their wealth and resources vastly outstrip those of Russia.

Bilateral aid to Ukraine: U.S. vs. key European allies

What are the challenges of increasing the European share of military aid?

Much of the aid sent to Ukraine has come from pre-existing weapons stockpiles. However, European stocks are shallow and major defense firms lack the capacity to quickly scale up production. Exact data on European stockpiles are not publicly available, but multiple European defense and security sources have said “that there are serious concerns at just how much of Europe’s ammunition has been used on the battlefield and not replaced.” While geopolitical conditions have changed, it is unlikely that European militaries will be fielding larger arsenals for a long time.

Some analyses indicate the stockpiles of major European militaries wouldn’t last more than a month during a high-intensity war. The Royal United Services Institute reports: “At the height of the fighting in Donbas, Russia was using more ammunition in two days than the entire British military has in stock. At Ukrainian rates of consumption, British stockpiles would potentially last a week.” The British parliamentary Defence Committee reports that it would take ten years to rebuild the stocks of the weapons sent to Ukraine.

A Wall Street Journal article from December 2023 illustrates similar issues across Europe: “The British military… has only around 150 deployable tanks and perhaps a dozen serviceable long-range artillery pieces. France, the next biggest spender, has fewer than 90 heavy artillery pieces… Denmark has no heavy artillery, submarines or air-defense systems. Germany’s army has enough ammunition for two days of battle” and 200 tanks, “only half of which are likely operational, according to government officials. The country’s industry can make only about three tanks a month, these officials said.”

While overall European defense spending has increased since the Russian invasion of Ukraine, in the short term, European industrial capacity is unable to meet increased demand. Despite purported commitments of increased military spending, defense companies want contracts in hand before they commit to the necessary production expansion, and these contracts have yet to be delivered by European governments. This is the result of three major trends impacting production and European defense planning.

First, judging that involvement in a high-intensity conflict was unlikely, European governments cut spending on excess capacity and instituted restrictive export controls (exports make for decreased domestic demand) after the Cold War. Moreover, issues of prioritization plague current production: “procurements of high-profile platforms such as aircraft and ships are routinely prioritised over mundane kit such as basic ammunition, rockets or even ground-based air-defence missiles.” Today, Europe’s defense industry is structured to produce a limited number of exquisite high-end weapons rather than a large number of systems and platforms for a sustained high-intensity conflict.

Second, material and labor shortages have made it difficult for European firms to ramp up production quickly. As one industry leader noted, “most of the raw materials necessary for the production of military products are not mined or are minimally mined in EU countries today.” Similarly, weapons production requires workers with specialized training and skills—something that takes years to develop, especially after decades of industry shrinkage.

Third, European governments have not pursued long-term contracts (i.e., 10 to 15 years) to guarantee orders for defense firms beyond the immediate term. Despite government pledges to increase defense spending, European firms have not taken steps to prepare for large-scale expansions of their production capacity because governments haven’t provided them with the contracts that would serve as a hedge against decreases in demand if the Ukraine war slows down or ends.

More on Europe

Featuring Jennifer Kavanagh

April 17, 2025

April 8, 2025

Events on Ukraine-Russia