February 16, 2021

After “maximum pressure”: returning to deterrence and diplomacy with Iran

The highest U.S. priority vis-à-vis Iran is avoiding an unnecessary war

This year will see new presidents in both the U.S. and Iran. The questions of whether and how to reenter the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) confront the new Biden administration. It is an ideal time to review broader U.S. policy toward Iran.

U.S. security interests regarding Iran are narrow and under less threat than many suggest:

- The U.S. does not want significant, long-term disruptions to the global oil supply, and preventing a regional hegemon achieves that. Iran lacks the conventional military power to seize oil-producing territory from its wealthy neighbors, let alone hold it against U.S. and international counteroffensives.1The Defense Intelligence Agency’s 2019 report Iran Military Power depicts a military only beginning, in the 2016–2018 timespan, to seek offensive capabilities and test them in exercises, while retaining a doctrine of deterrence by punishment—one poorly suited to seizing territory. See Iran Military Power: Ensuring Regime Survival and Securing Regional Dominance, Defense Intelligence Agency, 2019: 22–23.

- The U.S. does not want Iran to sponsor or launch terrorist attacks against the U.S., but the prospect of brutal retaliation deters that.

- Diplomacy is the only realistic way to prevent Iran from getting a nuclear weapon; even preventive military strikes will only delay Iran’s nuclear program while incentivizing Tehran to complete it.

- The U.S. does not want Iran to be able to coerce it with nuclear weapons, but the massive U.S. nuclear deterrent makes this threat toothless. Beyond self-defense, Iranian nuclear coercive threats would lack credibility, as has been the case with other nuclear powers.2Todd S. Sechser and Matthew Fuhrmann, Nuclear Weapons and Coercive Diplomacy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017).

At the same time, the opportunity cost of a U.S. war—and even friction—in the Middle East is growing. The U.S. is dealing with a major pandemic and severe economic disruption at home. Forces deployed to the Middle East are not available for needs that arise in more critical theaters—East Asia, for example—or for the training and maintenance that recent years of high operational tempo have delayed. Resources invested in the Middle East are not available for investment in America. Despite this, the U.S. retains thousands of troops in Syria, Iraq, and the Gulf on missions either directly responsive to tensions with Iran or aimed to deny Iran-friendly forces territory and political maneuvering room.

Further, the potential utility of military options against Iran is limited. Iran’s population (82 million) is twice as large as Iraq’s, and its territory (636,400 square miles) is more than three times larger and heavily mountainous. This effectively takes regime change by invasion off the table as a serious goal. A military attack on Iran’s nuclear or missile programs could severely damage them, for a time, but it is difficult to prevent a middle power from developing a 70-year-old technology, especially if it determines that technology could guarantee regime survival and prevent future devastation. Aerial and naval attacks on more general Iranian military and economic targets would struggle to inflict a decisive blow, since such campaigns have had limited success in the past in the absence of ground forces.3John J. Mearsheimer, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics (United States: W. W. Norton, 2003): 83–137. So any strategically transformative military option would likely require a ground invasion.4Barry R. Posen, “Courting War,” Boston Review, March 3, 2020, http://bostonreview.net/war-security/barry-r-posen-courting-war.

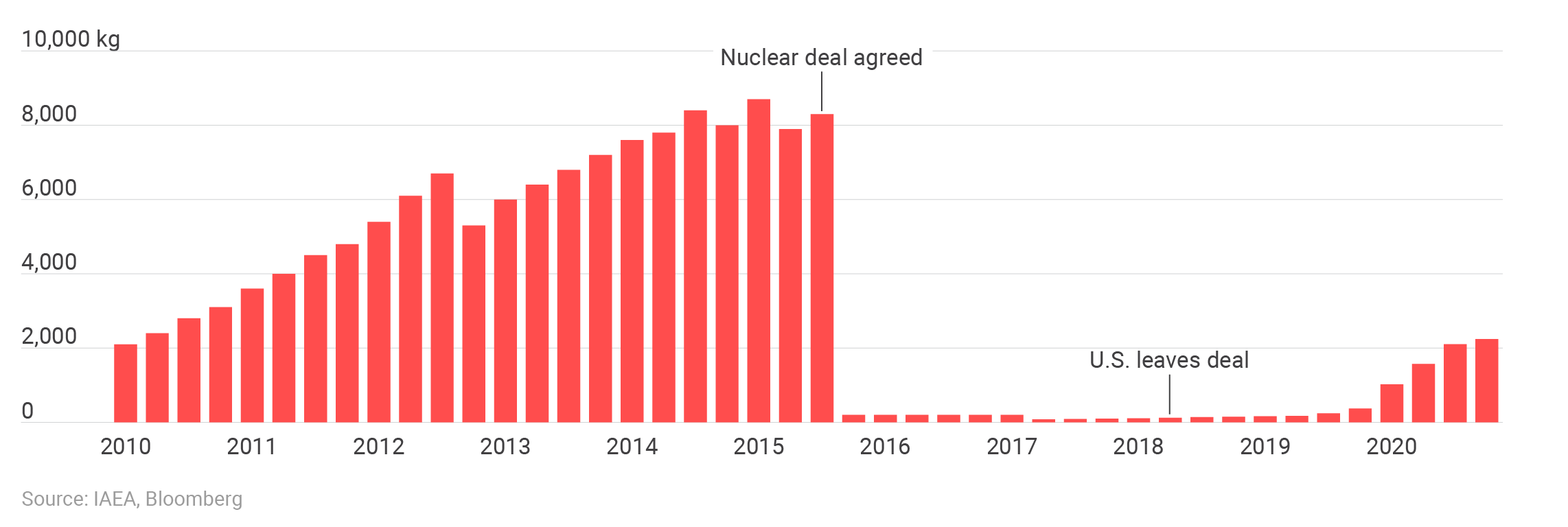

Iran’s enriched-uranium stockpile

The JCPOA limited Iran’s enriched-uranium stockpile to 202.8 kg, which Tehran began exceeding in 2019, one year after the U.S. withdrew from the agreement.

A war with Iran is therefore very unlikely to succeed. The war would also come with many risks: wider escalation, crippling costs, further entanglement in the Middle East, and deeper global economic disruption. So avoiding war with Iran is the main bilateral goal for the United States. Reducing tensions with Iran and increasing reliance on regional partners’ ability to balance Iran and defend themselves would enable the U.S. to pull resources away from the region, bringing costs and attention more in line with its narrow security interests.

“Maximum pressure” is a failed strategy

Proponents of the Trump administration’s “maximum pressure” strategy against Iran argued it would get a better nuclear deal and moderate Iran’s foreign policy. The strategy has achieved the opposite. It has made war more likely, increased Iranian attacks, and encouraged Iran to advance down the nuclear path. And it has strengthened hardliners, rather than undermined them. It is not even clear that the strategy has given the U.S. leverage to get an expanded deal, since Iran has sought leverage of its own on several fronts.

On the nuclear front, the Iranians waited a full year before responding to the May 2018 U.S. exit from the JCPOA by increasing their uranium stockpiles and their use of advanced centrifuges far beyond levels permitted by the framework. Iran recently resumed enriching uranium to near-20 percent purity, a level at which little further work needs to be done to reach nuclear-weapons grade, and working on uranium metal, which also has weapons applications. After the assassination of Iranian nuclear scientist Mohsen Fakhrizadeh in November 2020, Iran increased the budget of Fakhrizadeh’s research organization (SPND) by 256 percent. SPND is often seen as a successor organization to Iran’s pre-2003 nuclear weapons program. Iranian intelligence minister Mahmoud Alavi even recently hinted that Iran, if cornered, could acquire a nuclear weapon despite the Supreme Leader’s fatwa against it. Despite all this, and even with the U.S. out and Iran only partially implementing its commitments, the JCPOA remains the most meaningful limit on Iran’s nuclear program. The agreement also provides an irreplaceable source of intelligence on the program.

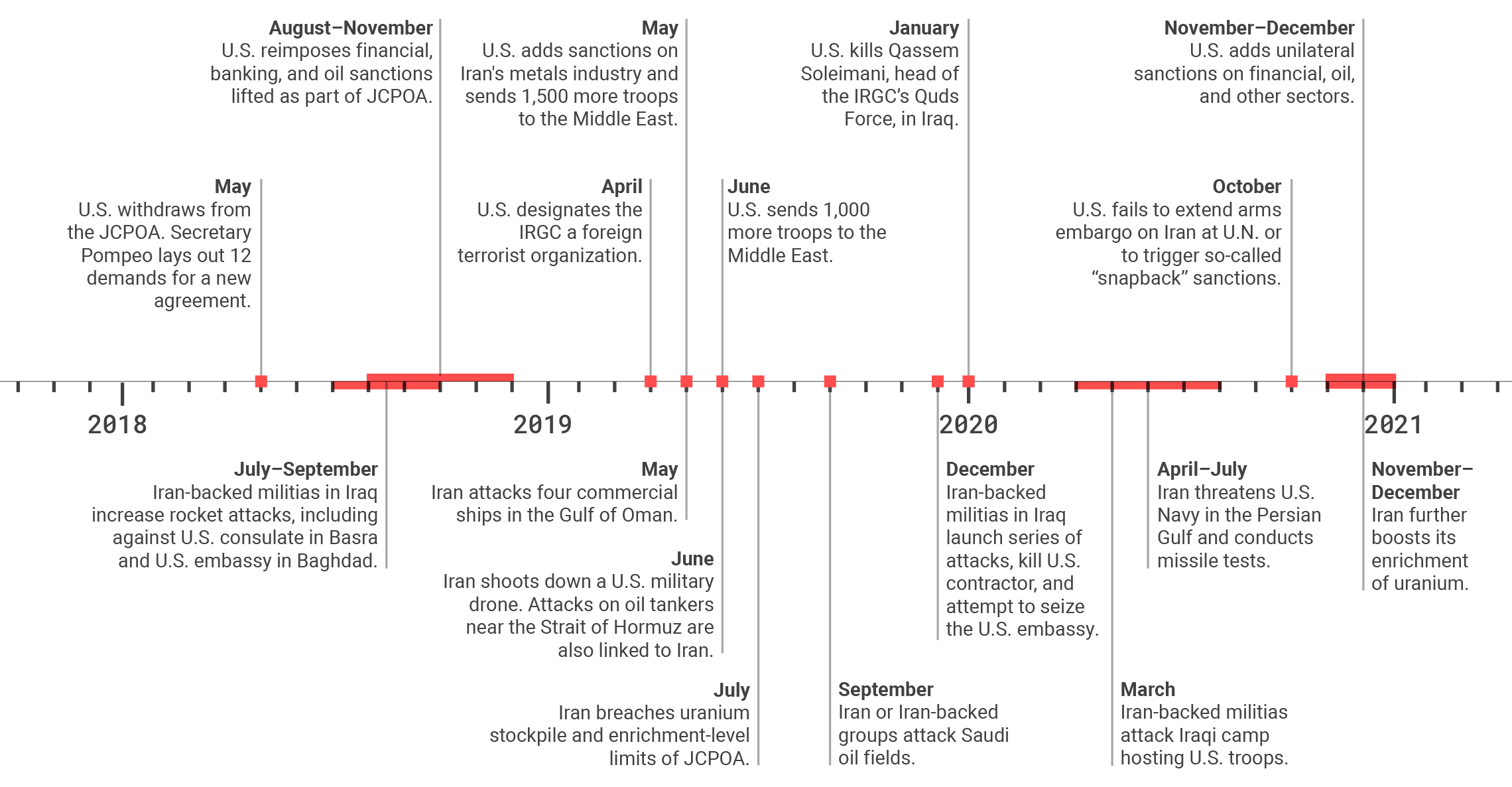

Timeline of “maximum pressure” strategy

The “maximum pressure” strategy increased confrontation between the U.S. and Iran over many areas and issues.

On the security front, the “maximum pressure” strategy has coincided with a major increase in Iranian and Iranian-supported violence, including attacks at Saudi Arabia’s Abqaiq oil facility, in the Gulf of Oman, and off the United Arab Emirates’ Fujairah port: rocket and ballistic missile strikes on American facilities in Iraq; the downing of a U.S. reconnaissance drone: and a militia-sponsored protest at the U.S. embassy in Baghdad. Fears about Iranian attacks repeatedly led the previous administration to dispatch additional military forces to the region, draw down diplomatic presence, and conduct military actions, like killing Iranian IRGC Gen. Qassem Soleimani and targeting Iraqi militias. The U.S. nearly conducted direct strikes on Iran in the wake of the drone shootdown in June 2019. Many of these attacks appear to have been calculated responses to U.S. actions, suggesting different U.S. actions could have yielded less violence.

Diplomacy, too, has floundered. The only publicly known diplomatic progress between the United States and Iran during the “maximum pressure” period has been a prisoner exchange in 2019. Future diplomacy with Iran may be hindered by the U.S. withdrawal from the nuclear deal, which makes U.S. commitments appear, in Iranian eyes, unreliable. This perception discourages international businesses from investing in Iran even in the event of sanctions relief, reducing the value of such an offer. This diminishes potential leverage accumulated through the “maximum pressure” campaign’s added sanctions.

Some advocates of the “maximum pressure” strategy seem to believe it might lead to regime change within Iran once Iranians, immiserated under sanctions, revolt against their leadership. All other things being equal, it would be good if Iran were governed by a responsive, transparent, non-authoritarian system. But all other things are not equal, and recent history in the region should give pause to those who argue the removal of a bad government will necessarily yield a better government. The “maximum pressure” strategy is not likely to lead to positive political change in Iran; indeed, it empowers actors like the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), which has absorbed many distressed businesses and taken on a major role in smuggling. As Peter Beinart writes:

The academic literature is clear: Far from promoting liberal democracy, sanctions tend to make the countries subject to them more authoritarian and repressive. […] As sanctions make resources harder to find, authoritarian regimes hoard them. They make the population more dependent on their largesse, and withhold resources from those who might threaten their rule.5Peter Beinart, “How Sanctions Feed Authoritarianism,” Atlantic, June 5, 2018, https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2018/06/iran-sanctions-nuclear/562043/.

In sum, the “maximum pressure” strategy has increased the danger of war and aided hardliners in Iran while not merely failing to deliver on its promises of a more docile, less nuclear Iran, but also making Iran more aggressive and accelerating its nuclear program.

The way forward is not only about the nuclear deal

Restoring the JCPOA offers a natural place to begin a reorientation of U.S.-Iran policy. It will immediately bring down Iran’s stockpiled nuclear materials. The regular diplomatic contact embedded in the JCPOA created opportunities for further diplomacy, such as the rapid release of U.S. Navy sailors who had been detained by the IRGC Navy after mistakenly entering Iranian waters in January 2016. Restoring basic communication channels will reduce the risk of unintended escalation amid tensions.

Rejoining the deal should be part of a shift in the U.S. posture in the Middle East. More than 20,000 U.S. troops have been dispatched to the Middle East to support that campaign or deal with its fallout.6Lolita C. Baldor, “U.S. General Says Troop Surge in Middle East May Not End Soon,” AP, January 23, 2020, https://apnews.com/article/2208d8645ac0437024ac71c06fcfb8e1. These troops should return home. While the U.S. has narrow security interests regarding Iran, it may wish to pursue other goals, such as limiting Iran’s missile capabilities or improving human rights. Measures that raise the risk of war should be avoided given the secondary nature of these interests.

When the JCPOA was in effect, Iranian officials sometimes expressed skepticism of pursuing further deals covering issues beyond the nuclear program. That skepticism has only grown because of “maximum pressure.” A less tense U.S.-Iran relationship may create openings for further diplomacy over time, but this will likely require years of confidence-building.

Even if both nations fail to get back into the JCPOA, the U.S. remains capable of deterring and defeating Iranian offensives. Iran gets a vote in whether the JCPOA is restored, but either way, Iran’s military is not built to seize territory from neighbors, and even if it were, its neighbors are well-equipped, and the U.S. military remains far stronger than Iran.7Iran Military Power, 2019. Similarly, if Iran continues to expand its nuclear program, the U.S. retains the option it has used with the Soviet Union/Russia, China, and North Korea: deterrence. Deterrence held against these states for a combined 141 years.8Calculated from the date of the state’s first test. Add in the India-Pakistan and India-China dyads, and the world has two centuries of successful deterrence. With the threat from Iran narrow, the U.S. should reduce Iran’s centrality in its foreign policy, while ultimately moving toward the normalized but difficult relationships it has with various other autocracies.

Endnotes

- 1The Defense Intelligence Agency’s 2019 report Iran Military Power depicts a military only beginning, in the 2016–2018 timespan, to seek offensive capabilities and test them in exercises, while retaining a doctrine of deterrence by punishment—one poorly suited to seizing territory. See Iran Military Power: Ensuring Regime Survival and Securing Regional Dominance, Defense Intelligence Agency, 2019: 22–23.

- 2Todd S. Sechser and Matthew Fuhrmann, Nuclear Weapons and Coercive Diplomacy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017).

- 3John J. Mearsheimer, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics (United States: W. W. Norton, 2003): 83–137.

- 4Barry R. Posen, “Courting War,” Boston Review, March 3, 2020, http://bostonreview.net/war-security/barry-r-posen-courting-war.

- 5Peter Beinart, “How Sanctions Feed Authoritarianism,” Atlantic, June 5, 2018, https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2018/06/iran-sanctions-nuclear/562043/.

- 6Lolita C. Baldor, “U.S. General Says Troop Surge in Middle East May Not End Soon,” AP, January 23, 2020, https://apnews.com/article/2208d8645ac0437024ac71c06fcfb8e1.

- 7Iran Military Power, 2019.

- 8Calculated from the date of the state’s first test. Add in the India-Pakistan and India-China dyads, and the world has two centuries of successful deterrence.

More on Middle East

Featuring Jennifer Kavanagh

April 17, 2025