December 4, 2024

Allies balancing: A safer strategy for the U.S. in Asia

By Rajan Menon and Daniel DePetris

Key points

- As China’s wealth and military power have increased, the United States has responded with a combination of military deployments in East Asia, regular military exercises in regional waterways, and stronger alliances. These steps have been accompanied by restrictions on the Chinese economy, including sanctions, export controls, and bans on U.S. investments in sectors deemed sensitive from the standpoint of U.S. security.

- These policies reflect the idea that only though primacy—military preponderance—can the United States protect its key interests in East Asia.

- These interests are traditionally seen as: (1) avoiding war with China unless it is essential for defending vital U.S. national security interests, (2) preserving access to the region’s markets, and (3) ensuring that China cannot dominate the region.

- Yet the balance of power in Asia is stabler than conventional wisdom suggests. Given Asia’s geography, China’s internal constraints, and resistance from Asia’s middle powers, Beijing cannot easily dominate East Asia.

- The best way forward is to maintain a favorable regional balance of power that does not rest on U.S. hegemony. This approach would shift defense burdens onto capable allies, especially South Korea and Japan, and better safeguard U.S. interests by ensuring regional stability while lowering the risk of war.

Introduction

To the extent the United States has a grand strategy in East Asia, it is based almost exclusively on containing China’s power. The 2022 U.S. National Defense Strategy described China as the Pentagon’s “pacing challenge.”1“2022 National Defense Strategy of the United States of America,” U.S. Department of Defense, October 27, 2022, https://media.defense.gov/2022/Oct/27/2003103845/-1/-1/1/2022-NATIONAL-DEFENSE-STRATEGY-NPR-MDR.pdf, 10. U.S. Congress, Senate, Foreign Relations Committee, “Evaluating U.S.-China Policy in the Era of Strategic Competition,” 118th Congress, February 9, 2023. See, in particular, the statement of Ely S. Ratner, assistant secretary of defense for Indo-Pacific Security Affairs. Dr. Ely Ratner, the assistant secretary of defense for Indo-Pacific security affairs, identified China as a revisionist power that increasingly resorts to “dangerous, coercive and aggressive actions” in the Indo-Pacific theater.2U.S. Congress, Senate, Foreign Relations Committee, “Evaluating U.S.-China Policy in the Era of Strategic Competition,” 118th Congress, February 9, 2023. See, in particular, the statement of Ely S. Ratner, assistant secretary of defense for Indo-Pacific Security Affairs. The Biden administration’s 2022 Indo-Pacific Strategy makes numerous references to China’s violations of the so-called rules-based international order—including its expansive claims in the South China Sea, saber-rattling against Taiwan, and economic coercion of its neighbors. The document stresses that the response by the United States and its allies will determine “whether the PRC succeeds in transforming the rules and norms that have benefited the Indo-Pacific and the world.”3“Indo-Pacific Strategy of the United States,” White House, February 2022, 5, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/U.S.-Indo-Pacific-Strategy.pdf

Realists find it unsurprising that China seeks to parlay its growing wealth into hard power and greater influence. As Kenneth Waltz wrote in The Theory of International Politics, states are in a constant struggle for power, control, and security because of the “anarchic” nature of the international system: in other words, the lack of a central authority with the capacity to maintain order and prevent or stop aggression.4Kenneth Waltz, The Theory of International Politics (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1979): 88. Consequently, states are insecure—forever unsure about the intentions of other states and driven to maximize their own power.5John Mearsheimer, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics (New York: W.W. Norton, 2001): 32–33.

China is no exception. Since the turn of the twenty-first century, its gross domestic product (GDP) has increased nearly 15-fold, from $1.21 trillion in 2000 to more than $17.79 trillion in 2023.6“China,” World Bank Group, https://data.worldbank.org/country/china. As measured in purchasing power parity (PPP), defined by the World Bank as the “total amount of goods and services a country’s currency can buy,” China’s economy overtook the U.S.’s in 2013. Not coincidentally, China’s military spending has increased during this period as well, with the People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) budget going up by more than 60 percent since 2013.7 “Trends in World Military Expenditure, 2022,” SIPRI, April 2023, https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/2023-04/2304_fs_milex_2022.pdf. A portion of China’s increased defense spending has been devoted to building up its nuclear deterrent.8Lyle Goldstein, “Raising the Minimum: Explaining China’s Nuclear Buildup,” Defense Priorities, April 5, 2022, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/raising-the-minimum-explaining-chinas-nuclear-buildup/. The Defense Department’s most recent report on PLA capabilities estimates that China now has approximately 500 operational nuclear warheads and could possess as many as 1,000 by 2030.9“Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2023,” U.S. Department of Defense, 2023, https://media.defense.gov/2023/Oct/19/2003323409/-1/-1/1/2023-MILITARY-AND-SECURITY-DEVELOPMENTS-INVOLVING-THE-PEOPLES-REPUBLIC-OF-CHINA.PDF.

These trends, in addition to China’s bolder behavior in parts of Asia, including its claims in the East China and South China seas, have led many experts to warn that China is poised to become a hegemon in Asia, meaning it would conquer or otherwise subjugate all rivals. U.S. policy must move aggressively to prevent this new China-led order in East Asia, this thinking goes, lest the U.S. position in the region be irreparably eroded and U.S. interests imperiled.10This is a consistent theme in Rush Doshi, The Long Game (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2021).

U.S. foreign policy officials have largely accepted this portrayal as fact and coalesced around a strategy of primacy, which aims to preserve U.S. dominance and unrivaled power over friends and adversaries alike.11Hal Brands, “Choosing Primacy: U.S. Strategy and Global Order at the Dawn of the Post-Cold War Era,” Texas National Security Review 1, no.2 (2018): 8–33. Militarily, that starts with maintaining the ability to take the lead in defending U.S. allies with forces stationed in theater even in peacetime and a U.S. Navy that maintains a high tempo of exercises and freedom of navigation operations in East Asian waters.12U.S. Congress, House of Representatives, Select Committee on the Strategic Competition Between the United States and the Chinese Communist Party, “The Biden Administration’s PRC Strategy,” 118th Congress, 2023. See especially the statement of Ely S. Ratner, assistant secretary of defense for Indo-Pacific Security Affairs. On the economic front, restrictions on technology exports to China, designed to maintain Washington’s technological edge and impede the modernization of the PLA, are now a key element in U.S. policy.13“Commerce Implements New Export Controls on Advanced Computing and Semiconductor Manufacturing Items to the People’s Republic of China (PRC),” Bureau of Industry and Security of the U.S. Department of Commerce, October 7, 2022, https://www.bis.doc.gov/index.php/documents/about-bis/newsroom/press-releases/3158-2022-10-07-bis-press-release-advanced-computing-and-semiconductor-manufacturing-controls-final/file. Diplomatically, the United States seeks to bring Southeast Asian states onto its side, even though many of them prefer to have beneficial relations with both the United States and China.14Van Jackson, “The Problem with Primacy: America’s Dangerous Quest to Dominate the Pacific,” Foreign Affairs, January 16, 2023, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/asia/problem-primacy.

The assumptions driving these policies, as well as the policies themselves, are dubious. Worse, they could set the United States and China on a collision course, something neither side seeks nor would benefit from given their military might. Even short of war, the intensifying and long-term rivalry between the United States and China that current policy embraces would heighten U.S. costs and risks, including by preventing collaboration and making dialogue on matters of mutual interest more difficult.

The United States’ core goals in East Asia are easier pursued than is generally assumed—and without a costly and risky strategy of primacy. Although the growth of China’s economic and military power over the last two decades is indisputable, other states have the agency to balance it. Indeed, they already are: Japan, South Korea, Australia, India, and the Philippines are increasing their defense capabilities and striking defense cooperation deals with each other.15Vasudevan Sridharan, “Can India Forge a 3-Way Partnership with Japan, South Korea to ‘Counter China’s Actions’?” South China Morning Post, March 11, 2024, https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/politics/article/3254959/can-india-forge-3-way-partnership-japan-south-korea-counter-chinas-actions; Takahashi Kosuke, “Japan, Philippines Agree to Intensify Defense Cooperation,” Diplomat, November 3, 2023, https://thediplomat.com/2023/11/japan-philippines-agree-to-intensify-defense-cooperation/; Keerthiraj and Takashi Sekiyama, “The Rise of China and Evolving Defense Cooperation between India and Japan,” Social Science 12, no. 6 (2023): 333; Mari Yamaguchi, “Japan and India Agree to Step Up Security and Economic Cooperation amid Regional Security Concerns,” AP News, March 7, 2024, https://apnews.com/article/japan-india-security-defense-economy-3cae228904b6b3efb6d173e2680d3f83; Rajat Pandit, “China Looming Large, India & Austria Crank Up Defence Partnership,” Times of India, November 21, 2023, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/china-looming-large-india-australia-crank-up-defence-partnership/articleshow/105366239.cms; Phelim Kine, Alexander Ward, and Lara Seligman, “US, Japan, Philippines Plan Joint South China Sea Naval Patrols,” Politico, March 29, 2024, https://www.politico.com/news/2024/03/29/us-japan-philippines-plan-joint-south-china-sea-naval-patrols-00149797. This trend should accelerate as China’s economic and military power grows. It’s highly unlikely that China’s neighbors—many of which, like Japan and South Korea, have significant military capacity and latent power of their own—would acquiesce to its efforts to dominate the region. Should China decide to wage a war of conquest on the continent, it would face additional obstacles, including Asia’s vast land mass, long borders, and nuclear-armed states (six of the world’s nine nuclear-armed states are in Asia).16William D’Ambruoso, “The Restraining Effect of Nuclear Deterrence,” Defense Priorities, June 16, 2023, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/the-restraining-effect-of-nuclear-deterrence/.

States with nuclear weapons in Asia

China has vast borders and is surrounded by nuclear-armed or nuclear-protected states, which would make any war for conquest exceedingly difficult.

This paper begins with a brief overview of what the U.S. seeks to accomplish in East Asia as a segue to explaining why the current U.S. strategy of primacy is unnecessary to meet those goals and would lead to a greater likelihood of crises. It then outlines why East Asia’s geopolitical landscape is more stable than is generally appreciated and why that should allow the United States to devolve greater responsibilities to its allies—relying on balancing behavior rather than U.S. dominance to preserve stability. This is especially true on the Korean Peninsula, where South Korea holds vast economic, technological, and military advantages over North Korea. It also presents a series of recommendations to lower the likelihood of escalation in East Asia, reduce the costs in American blood and treasure, and move South Korea and Japan, two principal U.S. allies, toward assuming greater responsibility for their own defense.17Rajan Menon, The End of Alliances (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007): chapters 4 and 5.

What the U.S. wants in East Asia

Before delving into a balancing strategy, it is necessary to enumerate what the United States seeks to achieve in the region. At bottom, the United States has three traditional goals in East Asia: (1) averting war with China; (2) preserving access to Asian markets; and (3) ensuring Asia isn’t dominated by a single power, principally China. Many proponents of restraint would argue one or both of the latter two goals are sound in principle but in little peril today. But even if we take these three objectives as a starting point, the current U.S. approach toward realizing them—forward deployments of U.S. military power, frequent military exercises with regional allies and partners, the formation of a de facto anti-China bloc—is resource-intensive and carries significant risk. Thankfully the U.S. can also accomplish them through more restrained means that rely more on allies and lower the chances of escalation.

The first perceived interest, avoiding war, is imperative given the massive economic, diplomatic, and humanitarian consequences that would accompany an armed conflict with China. War simulations between U.S. and Chinese forces paint a dire picture. Even if the conflict were to stay conventional—a big if—both sides would suffer tens of thousands of casualties and a degradation of their respective militaries. Other states, including U.S. allies like Japan and even South Korea, could be dragged into the conflagration and targeted by Chinese missiles because of the presence of U.S. bases on their territories. A January 2023 war game conducted by the Center for Strategic and International Studies on the consequences of a conflict in the Taiwan Strait found that the U.S. military would suffer enormous losses even if it were to ultimately prevail.18Mark F. Cancian, Matthew Cancian, and Eric Heginbotham, “The First Battle of the Next War: Wargaming a Chinese Invasion of Taiwan,” Center for Strategic & International Studies (CSIS), January 9, 2023, https://www.csis.org/analysis/first-battle-next-war-wargaming-chinese-invasion-taiwan.

The economic costs of a war with China must also be considered.19Sara Hsu, “Avoiding a Costly China-US Conflict,” Diplomat, April 28, 2023, https://thediplomat.com/2023/04/avoiding-a-costly-china-us-conflict/. U.S.-China bilateral trade was valued at $575 billion in 2023.20“2023: U.S. Trade in Goods with China,” United States Census Bureau, https://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/balance/c5700.html. In May 2024, despite extensive U.S. tariffs on Chinese imports, China was the third largest U.S. trading partner, accounting for over 10 percent of total U.S. trade.21“Top Trading Partners- May 2024,” United States Census Bureau, https://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/statistics/highlights/topcm.html. A Sino-American war would jeopardize these trade flows and lead China to withhold products and materials that the U.S. economy relies on.22Ross Babbage, “A War with China Would Be Unlike Anything Americans Faced Before,” New York Times, February 27, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/02/27/opinion/a-war-with-china-would-reach-deep-into-american-society.html. The ramifications would be global and long-lasting given that about 80 percent of the world’s maritime trade passes through Asia, with one-third transiting the South China Sea.23“How Much Trade Transits the South China Sea?” China Power, August 2, 2017, updated January 25, 2021, https://chinapower.csis.org/much-trade-transits-south-china-sea/.

U.S. trade with China over time

Some analysts contend that U.S. alliances in East Asia and the security benefits Asian states receive from Washington—up to and including extended deterrence, the United States’ implied commitment to use its full military power to defend an ally, including with nuclear weapons if necessary—will prevent a war with China and preserve order.24Mira Rapp-Hooper, “Saving America’s Alliances: The United States Still Needs the System That Put It on Top,” Foreign Affairs, February 10, 2020, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2020-02-10/saving-americas-alliances. “GDP Based on PPP, Share of World,” International Monetary Fund (IMF), accessed July 14, 2024, https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/PPPSH@WEO/OEMDC/ADVEC/WEOWORLD. But such alliances aren’t risk-free for the United States, particularly when its treaty allies (like Japan and the Philippines) have unresolved disputes with China over maritime boundaries or, in the case of South Korea, are still technically in a state of war with a hostile, nuclear-armed North Korea, which is closely aligned with Beijing. It is hardly unreasonable to assume that the United States would be drawn into the fray were clashes between China and a U.S. ally to spiral into full-blown war.

The second U.S. goal is to preserve U.S. market access and sustain an open regional economy in East Asia, which accounts for more than 25 percent of global GDP.25“GDP Based on PPP, Share of World,” International Monetary Fund (IMF), accessed July 14, 2024, https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/PPPSH@WEO/OEMDC/ADVEC/WEOWORLD. Of the top 10 U.S. trading partners between February 2023 and February 2024, four were in East Asia.26“U.S. Goods Trade with Global Partners,” International Trade Administration, accessed July 14, 2024, https://www.trade.gov/data-visualization/us-goods-trade-global-partners. U.S. foreign direct investment in the Asia-Pacific reached $951 billion in 2022, a 350 percent increase since 2002.27“Direct Investment by County and Industry, 2022,” Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), July 20, 2023, 5, https://www.bea.gov/sites/default/files/2023-07/dici0723.pdf. With 60 percent of the world’s population, U.S. officials believe Asia will be the principal source of global economic growth for the next three decades.28“Fact Sheet: In Asia, President Biden and a Dozen Indo-Pacific Partners Launch the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity,” White House, May 23, 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/05/23/fact-sheet-in-asia-president-biden-and-a-dozen-indo-pacific-partners-launch-the-indo-pacific-economic-framework-for-prosperity/. War, crises, and widespread protectionism in East Asia would have adverse effects on the U.S. economy by limiting the flow of raw materials, goods, and investments to and from the region. That, in turn, would have global ramifications.

This interest in open trade is often misconstrued as a license to patrol endlessly to protect sea-lanes in order to prevent every perceived threat to trade. But trade can be kept open with economic and diplomatic tools rather than military ones, which are more likely to precipitate crises that could escalate in ways that might prove unpredictable and difficult to control.

Third, the U.S. seeks to prevent any single power—in particular China—from dominating East Asia. According to some U.S. analysts, such a scenario would have geopolitical consequences for the United States, enabling Beijing to control strategic locations and establish primacy of its own.29H.R. McMaster, “How China Sees the World,” Atlantic, May 2020, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2020/05/mcmaster-china-strategy/609088/. Such an outcome could threaten the United States more directly or at least allow China to achieve a stranglehold on trade in Asia. But as will be discussed later, Asia’s middle powers are unlikely to sit by as China pursues hegemony in East Asia. That’s assuming China could even accomplish such a feat given East Asia’s vast geography, the nationalism within its respective countries, and the PLA’s deficiencies.30Steven Kosiak, “The Conventional Wisdom About the Chinese Military Challenge: Incomplete and Unpersuasive,” Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft, November 6, 2023, https://quincyinst.org/research/the-conventional-wisdom-about-the-chinese-military-challenge-incomplete-and-unpersuasive/#focus-on-taiwan-contingencies.

The pitfalls and perils of primacy

The current U.S. strategy in East Asia is primacy—the theory that the most effective way to preserve U.S. power, markets, and global peace is by keeping allies and partners dependent on the United States and maintaining military superiority over rivals and even friendly countries.31Stephen G. Brooks, G. John Ikenberry, and William Wohlforth, “Don’t Come Home, America: The Case Against Retrenchment,” International Security 37, no. 3 (2012/13): 7–51. Primacy strives to dampen geopolitical competition, to both deter adversaries and protect allies from costly rivalries.

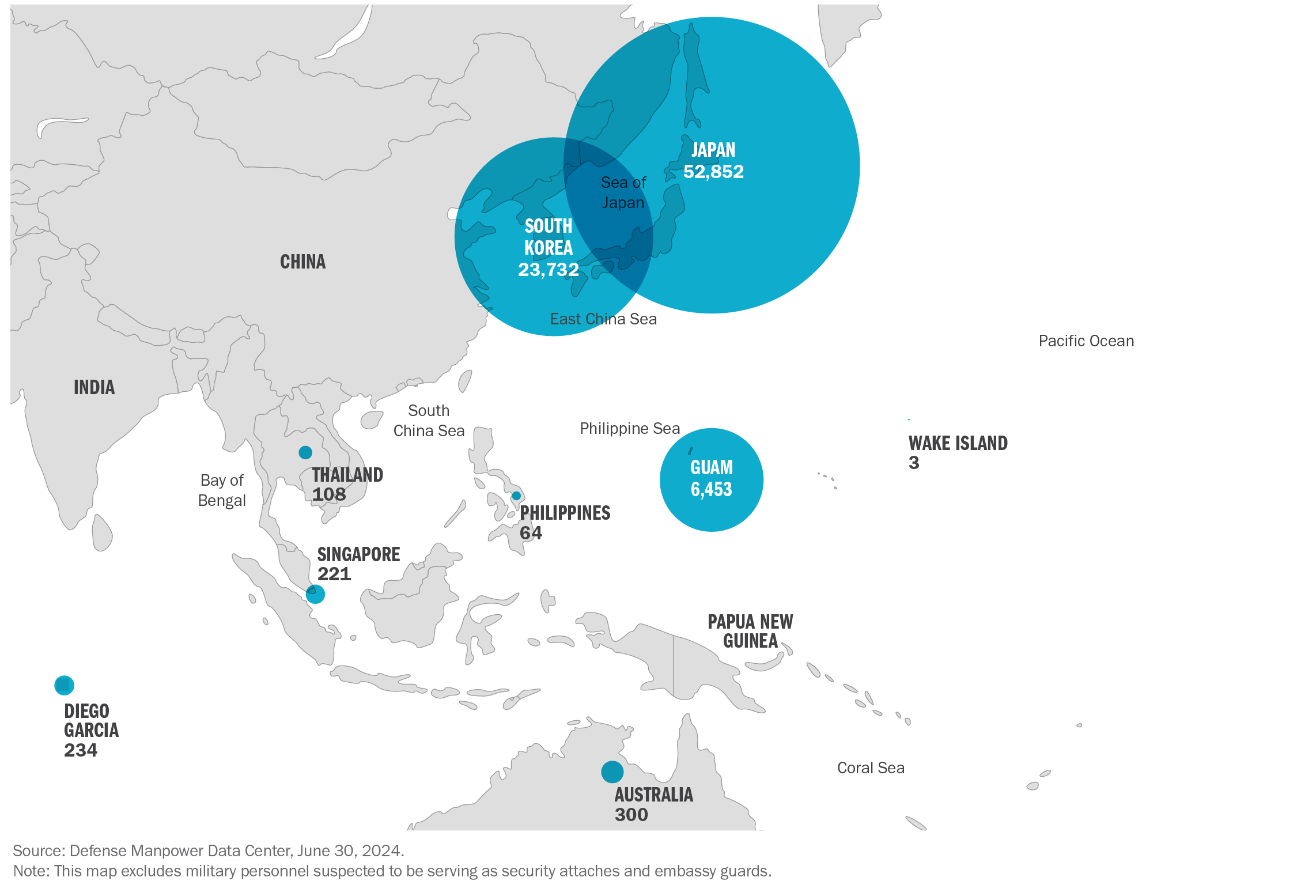

In East Asia, primacy is carried out through the United States’ extensive network of large bases and smaller military facilities, many of them byproducts of the post-World War II period. In Japan alone, 54,000 U.S. troops are distributed across 85 facilities.32“About USFJ,” U.S. Forces Japan, accessed July 14, 2024, https://www.usfj.mil/About-USFJ/. The U.S. also has more than 28,000 troops stationed in South Korea on a practically permanent basis.33“U.S.-South Korea Alliance: Issues for Congress,” Congressional Research Service (CRS) Report, September 12, 2023, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF11388. In the Philippines, the U.S. has access to nine bases, including in Luzon, which faces the Taiwan Strait and could conceivably be used during a Taiwan crisis.34Sui-Lee Wee, “U.S. to Boost Military Role in the Philippines in Push to Counter China,” New York Times, February 1, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/02/01/world/asia/philippines-united-states-military-bases.html. With more than 462,000 active-duty U.S. forces stationed in Hawaii and on the U.S. West Coast, the United States also has the ability to surge forces into the Asian theater in the event of a crisis, although maintaining access amid Chinese attacks would be challenging.35“Military and Civilian Personnel by Service/Agency by State/Country,” Defense Manpower Data Center (DMDC), December 2023, https://dwp.dmdc.osd.mil/dwp/app/dod-data-reports/workforce-reports.

U.S. forces permanently stationed in Asia

The United States uses its network of bases and tens of thousands of troops to attempt to maintain primacy in East Asia.

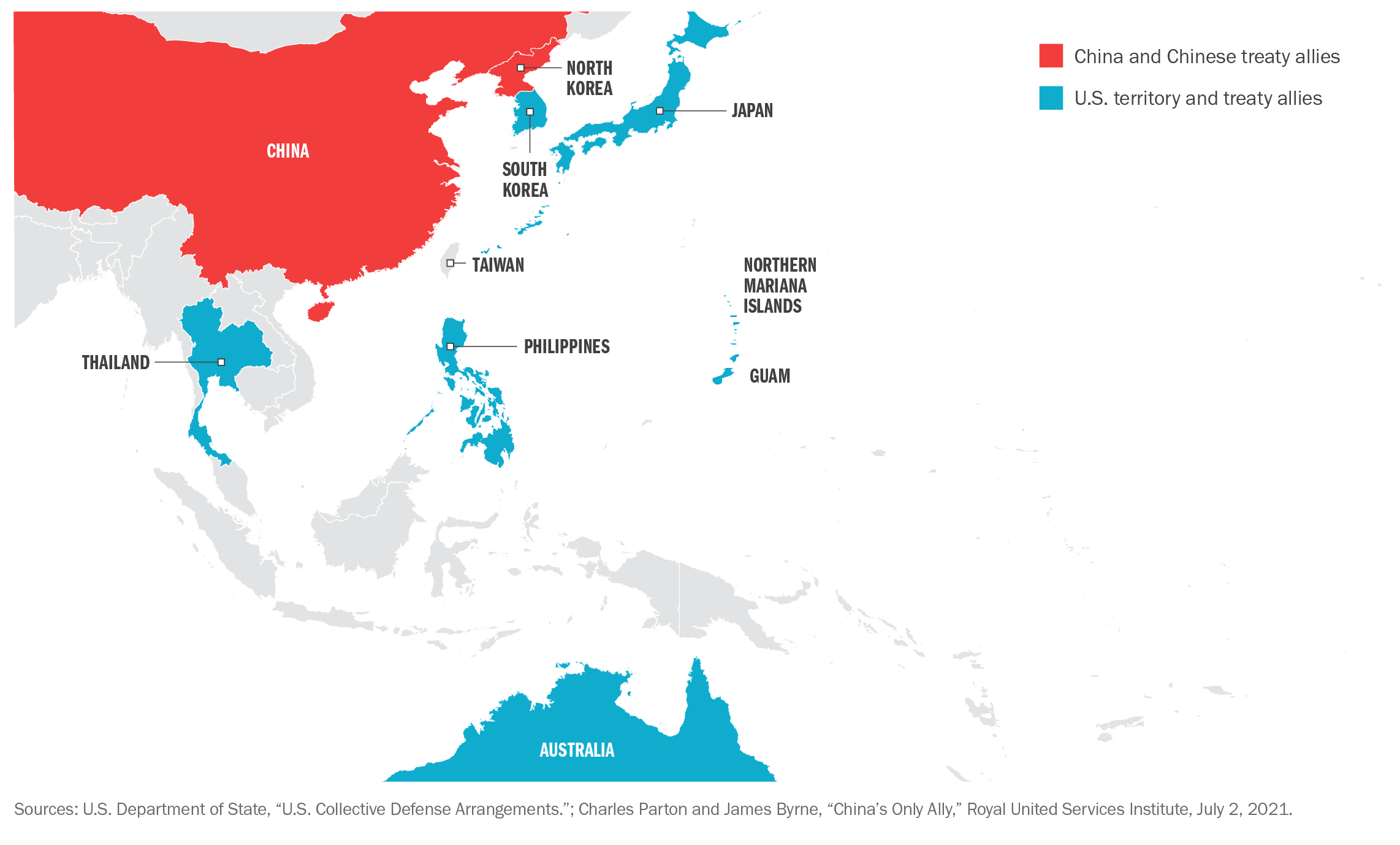

As U.S. treaty allies in East Asia, Japan, South Korea, and the Philippines receive U.S. defense guarantees. In the cases of Japan and South Korea, those commitments extend, in extremis, to the use of U.S. nuclear weapons against a nuclear-armed adversary like China if it attacks one or more of these countries.36Peter Harris, “Moving to an Offshore Balancing Strategy for East Asia,” Defense Priorities, October 21, 2023, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/moving-to-an-offshore-balancing-strategy-for-east-asia/. But this implied commitment—known as extended deterrence—suffers from credibility problems. The United States has enough conventional military power to come to the defense of its allies but may choose not to given China’s nuclear arsenal.37Michael J. Mazarr, “Understanding Deterrence,” RAND Corporation, 2018, https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/perspectives/PE200/PE295/RAND_PE295.pdf.

But primacy is a flawed theory for three big reasons: it backfires by alarming rivals and making them more likely to arm, it enfeebles capable allies, and it can nonetheless induce excessive risk-taking by allies.

First, the U.S. effort to maintain primacy in Asia has provoked the problems it tries to prevent. U.S. military capabilities in the region and frequent freedom-of-navigation patrols and large military exercises make Beijing wary and insecure, leading it to strengthen its own military in response. Similarly, on the Korean Peninsula, U.S. deployments of nuclear-capable submarines, large-scale drills with the South Korean military, periodic B-2 flyovers, and strengthened trilateral military collaboration between the United States, South Korea, and Japan have prompted North Korea to increase its nuclear weapons and to test, develop, and deploy an array of ballistic and cruise missiles.

The “security dilemma” (states responding to perceived insecurity by strengthening their defenses, rendering others insecure in the process and causing them to react) is a result of the U.S. quest for primacy in Asia.38John H. Herz, “Idealist Internationalism and the Security Dilemma,” World Politics 2, no. 2 (1950): 157–180. This extends to the nuclear realm as well: advances in U.S. conventional strike platforms, anti-missile systems, and the development of low-yield nuclear warheads have likely spurred China to increase its nuclear arsenal and expand its intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) force in order to preserve a second-strike capability.39Henrik Stålhane Hiim, M. Taylor Fravel, and Magnus Langset Trøan, “The Dynamics of an Entangled Security Dilemma: China’s Changing Nuclear Posture,” International Security 47, no. 4 (2023): 147–187.

U.S. and Chinese allies in the Asia-Pacific

By provoking security dilemmas and hastening, rather than tamping down, militarized rivalry in Asia, primacy plants the seeds of its own destruction.40Benjamin Schwarz and Christopher Layne, “A New Grand Strategy,” Atlantic, January 2002, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2002/01/a-new-grand-strategy/376471/. Other powers can’t afford to assume that a hegemon will use its power benevolently, thus spurring them to align with other great powers to protect themselves and defend their interests.41Stephen Walt, “American Primacy: Its Prospects and Pitfalls,” Naval War College Review 55, no. 2 (2002) https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol55/iss2/2. This is evident today: shared concerns about U.S. power have led to a growing strategic partnership between China and Russia, and to a lesser extent between Russia and North Korea. Reacting to what both regard as U.S. attempts to contain and undermine their power, China and Russia are now collaborating on military-related research and development projects, conducting bilateral military exercises, and coordinating at the United Nations Security Council to oppose U.S. diplomatic initiatives.42Daniel DePetris, “Perils of Pushing Russia and China Together,” Defense Priorities, August 5, 2021, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/perils-of-pushing-russia-and-china-together. The United States has in effect reversed its biggest Cold War-era accomplishment: averting an anti-U.S. alignment between Beijing and Moscow.

Second, even as it tends to provoke China, primacy encourages allies to under-resource their own armed forces and disincentivizes them from taking primary responsibility for their own security. This applies even to Taiwan, easily the state most endangered by China. Despite a recent boost, Taiwan spends just 2.5 percent of its gross domestic product on its military and has failed to address various deficiencies in its ability to head off a Chinese invasion.43Gordon Arthur, “Taiwan Boosts Defense Spending in Face of Chinese Military Prodding,” Defense News, August 23, 2024, https://www.defensenews.com/global/asia-pacific/2024/08/23/taiwan-boosts-defense-spending-in-face-of-chinese-military-prodding/; Michael A. Hunzeker, “Taiwan’s Defense Plans Are Going off the Rails,” War on the Rocks, November 18, 2021, https://warontherocks.com/2021/11/taiwans-defense-plans-are-going-off-the-rails/. Its defensive strategy assumes the United States will not only protect it indefinitely but also intervene militarily in the event China seeks to control Taiwan by force.44Raymond Kuo, “The Counter-Intuitive Sensibility of Taiwan’s New Defense Strategy,” War on the Rocks, December 6, 2021, https://warontherocks.com/2021/12/the-counter-intuitive-sensibility-of-taiwans-new-defense-strategy/. Similar if less acute dynamics are on display in the other Asian states under the U.S. security umbrella, like Japan and the Philippines. While they are far from inert before the growing Chinese threat, as discussed elsewhere in this paper, they would likely do a great deal more if U.S. assistance were less robust.

Further, the U.S. strategy of primacy and the alliance system underpinning it could encourage reckless behavior from U.S. allies, which may calculate that the United States would automatically come to their defense if they got involved in a crisis. Entrapment or entanglement, where a U.S. ally pursues a risky policy that pulls the United States into a conflict, could result from this kind of moral hazard.45Miranda Priebe et al., “Do Alliances and Partnerships Entangle the United States in Conflict?” RAND Corporation, 2021, https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RRA700/RRA739-3/RAND_RRA739-3.pdf. Moreover, the danger of the United States being drawn into a local conflict is high even if the ally in question does not act rashly.

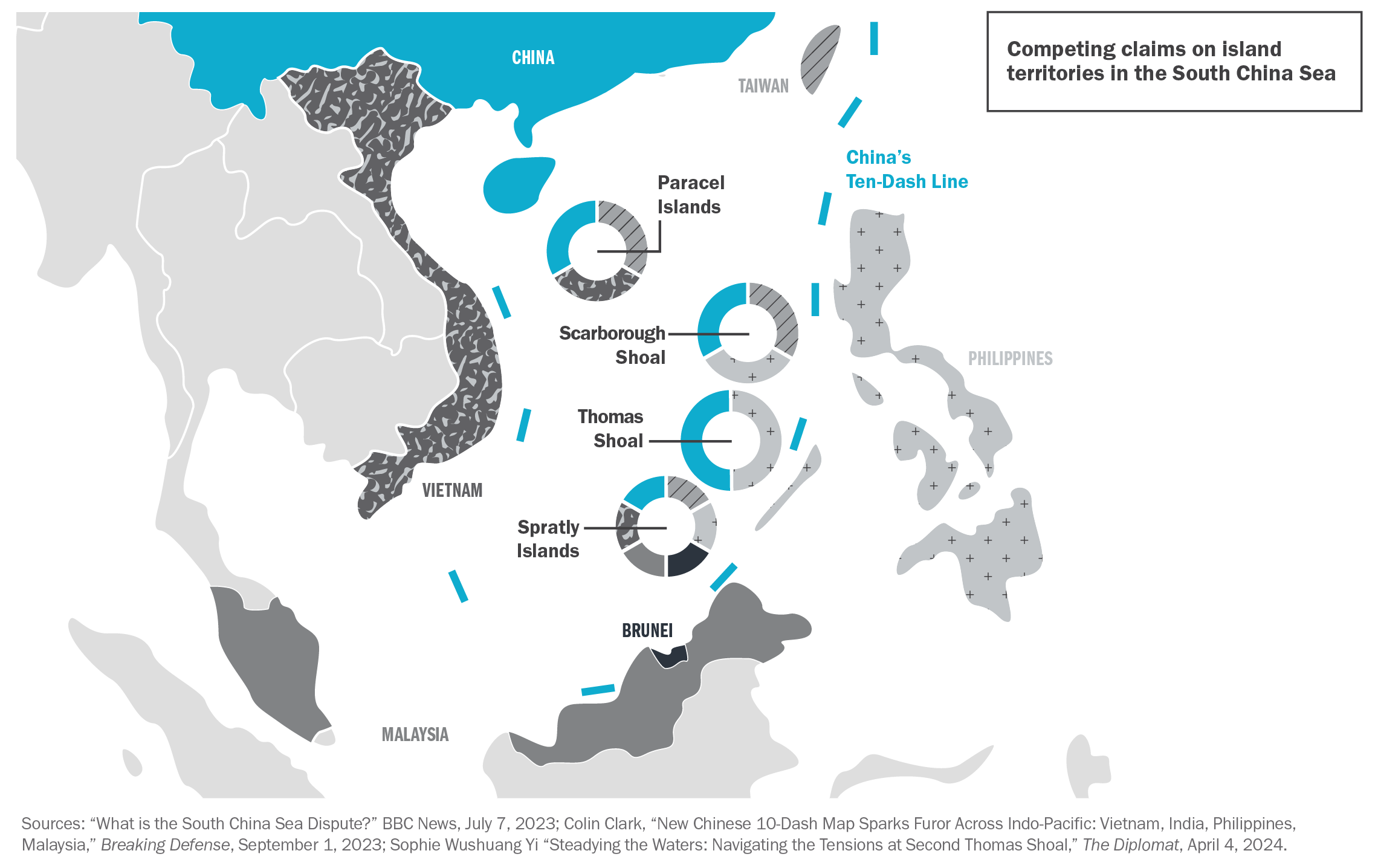

This is especially true in East Asia, where China has a number of territorial and maritime disputes with neighbors that also happen to be U.S. allies.46Michael C. Horowitz et al., “Policy Roundtable: Competing Visions for the Global Order,” Texas National Security Review, February 5, 2019, https://tnsr.org/roundtable/policy-roundtable-competing-visions-for-the-global-order/. One of those disputes centers on the Second Thomas Shoal in the South China Sea claimed by both China and the Philippines. The number of incidents between Chinese and Filipino vessels near the Shoal has increased since 2023 and the United States has warned China that any armed attack on the Philippines’ armed forces anywhere in the South China Sea would invoke the 1951 U.S.-Philippines Mutual Defense Treaty.47Matthew Miller, “U.S. Support for the Philippines in the South China Sea,” U.S. Department of State, March 5, 2024, https://www.state.gov/u-s-support-for-the-philippines-in-the-south-china-sea-8/. By making such a public commitment, the United States increases the chances of the Philippines acting more carelessly near these disputed features.48Lyle Goldstein, “Second Thomas Shoal Isn’t Worth War with China,” Asia Times, August 13, 2024, https://asiatimes.com/2024/08/second-thomas-shoal-isnt-worth-war-with-china/. The United States should act unilaterally to reduce this risk by changing its current policy and stating that Article 4 of the Mutual Defense Treaty does not apply to the Second Thomas Shoal or any other place in the South China Sea where China and the Philippines have conflicting claims.49“Mutual Defense Treaty Between the United States and the Republic of the Philippines,” accessed at Lillian Goldman Law Library, Yale Law School, August 30, 1951, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/20th_century/phil001.asp.

Chinese territorial disputes in the South China Sea

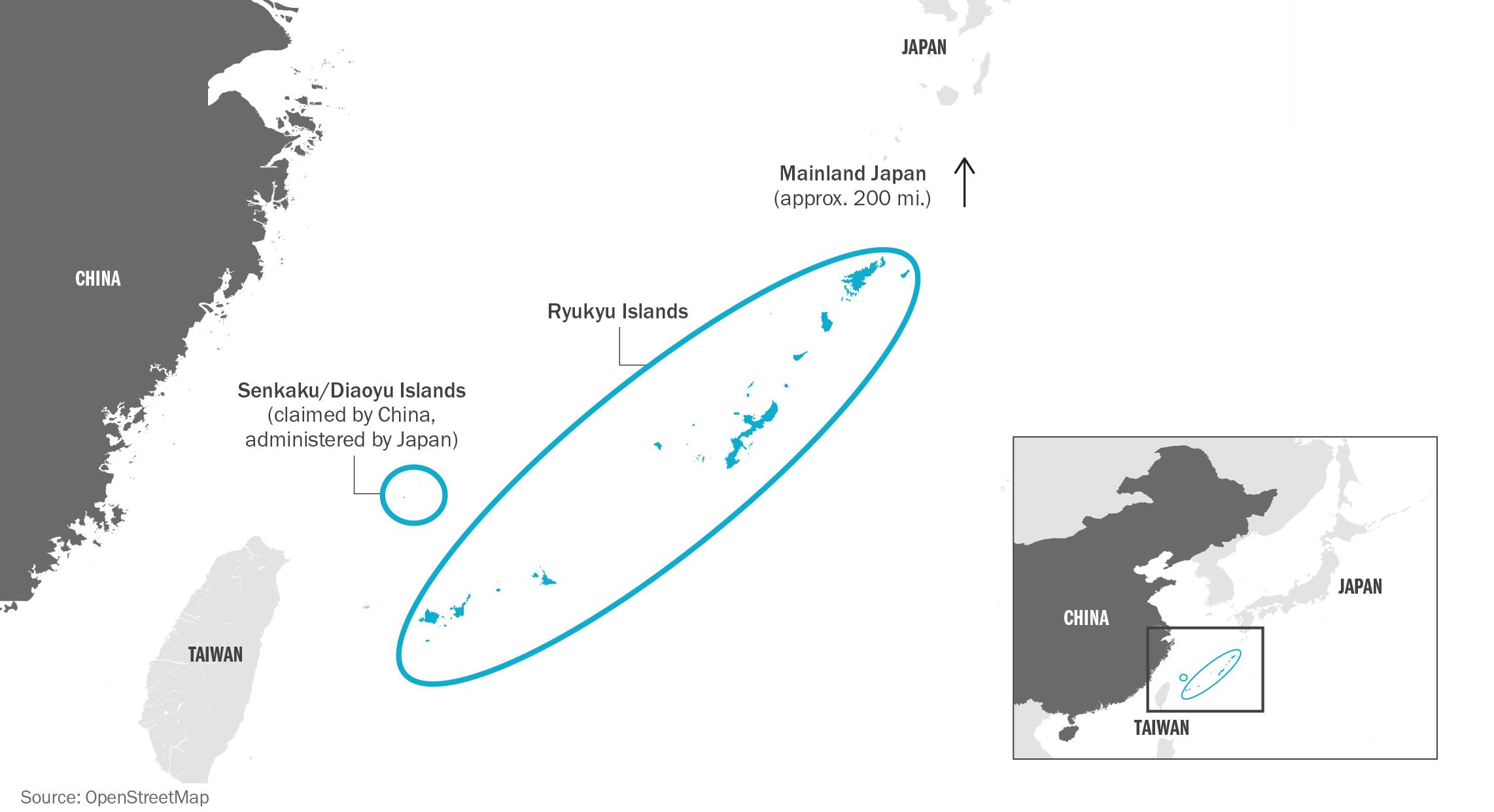

The decades-long dispute over the Japanese-administered Senkaku Islands, which China also claims, provides another example. In October 2023, U.S. Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin stated that the “ironclad” U.S. treaty-based commitment to defend Japan covered the Senkaku Islands.50“Mutual Defense Treaty Between the United States and the Republic of the Philippines,” accessed at Lillian Goldman Law Library, Yale Law School, August 30, 1951, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/20th_century/phil001.asp. Yet the Senkaku Islands remain a point of contention between the PLA and the JSDF. In April 2024 alone, the Japanese and Chinese coast guards mounted patrols in contested waters near the islands and had issued 10 warnings to each other as of mid-2024.51“China, Japan Coast Guards Patrol Disputed East China Sea Waters,” Reuters, April 12, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/china-japan-coast-guards-patrol-disputed-east-china-sea-waters-2024-04-12/ In March, Japan claimed that Chinese coast guard ships had entered the waters adjacent to the islands 96 days in a row.52John Feng, “Data Tracks China’s ‘Intrusions’ into Neighbor’s Disputed Territory,” Newsweek, March 26, 2024, https://www.newsweek.com/china-japan-coast-guard-maritime-vessels-senkaku-diaoyu-island-data-1883397. These are not new developments: in 2020, Japan, responding to stepped-up Chinese patrols—1,161 Chinese vessels had entered the islands’ contiguous zone by the end of that year—announced that it would increase the number of coast guard ships tasked with patrolling the surrounding waters by nearly 50 percent.53Feng, “Data Tracks China’s ‘Intrusions.’” For the increase in Japanese patrols, see Shohei Kanaya, “Japan to Bulk up Senkaku Patrols as More Chinese Ships Enter the Area,” Nikkei Asia, December 23, 2020, https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/Japan-to-bulk-up-Senkaku-patrols-as-more-Chinese-ships-enter-area. While China and Japan are wary of escalation, it’s unknown whether this restraint will hold in the long term.

Japanese islands in the first island chain

East Asia is balancing already

Although proponents of primacy fear that any U.S. retrenchment in Asia will compel U.S. allies and partners to appease or align with China, they are more likely to adopt strategies to counterbalance it.54Michael Desch, “War is a Choice, Not a Trap: The Right Lessons from Thucydides,” Defense Priorities, July 19, 2022, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/war-is-a-choice-not-a-trap/. The logic is straightforward: as a state becomes more powerful and ambitious, other states in its region respond by strengthening their own military capabilities and forging partnerships to counter the common threat.55Hans J. Morgenthau, Politics Among Nations: The Struggle for Power and Peace (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1948): 125.

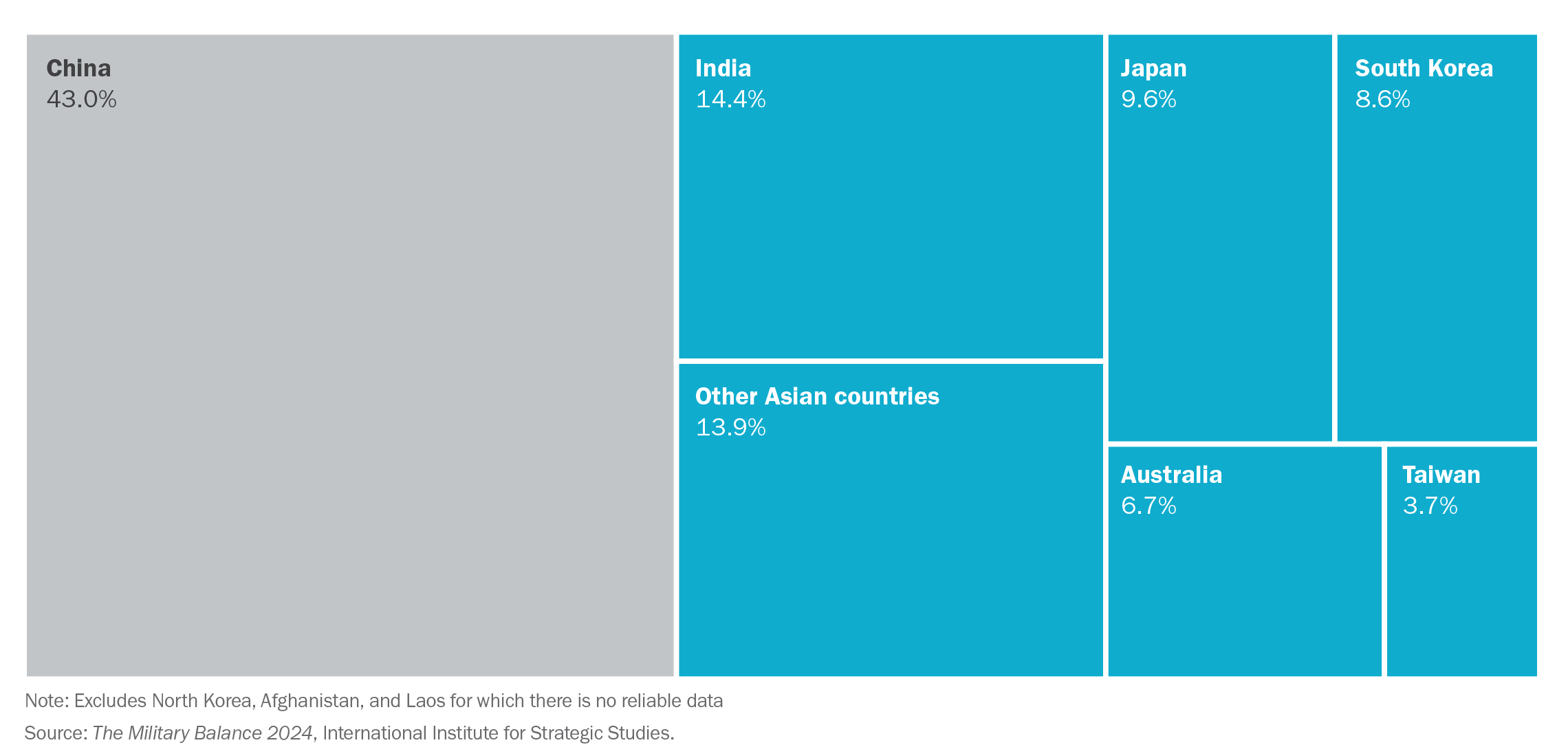

Proportions of total defense spending in Asia

China’s neighbors have already begun to adapt to its rise by increasing their defense budgets, acquiring counterstrike capabilities to improve deterrence, deepening military-to-military cooperation through bilateral military access agreements, and conducting routine joint military exercises. This is unsurprising: states tend to join forces when they perceive a common threat.56Stephen M. Walt, “Stop Worrying About Chinese Hegemony in Asia,” Foreign Policy, May 31, 2023, https://foreignpolicy.com/2023/05/31/stop-worrying-about-chinese-hegemony-in-asia/. The greater the perceived threat, the more likely that they will cooperate to counter it.

While the United States has sought to persuade allies and partners in Asia to treat China as a serious, long-term security challenge, the reality is that China’s neighbors already recognize that they must act to defend their security interests as China becomes more powerful. A September 2023 survey found that 76 percent of Japanese and 64 percent of South Koreans consider China’s power and influence to be a major threat to their security.57Laura Silver, Christine Huang, and Laura Clancy, “In East Asia, Many People See China’s Power and Influence as a Major Threat,” Pew Research Center, December 5, 2023, https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2023/12/05/in-east-asia-many-people-see-chinas-power-and-influence-as-a-major-threat/. Another survey from the same year found that nearly 70 percent of Filipinos have an unfavorable or highly unfavorable view of China, with 64 percent of Filipinos citing China’s destabilizing behavior in the region as the primary reason for those feelings.58Caroline Gray et al., “Caught in the Middle: Views of US-China Competition Across Asia,” Institute for Global Affairs, June 2023, https://instituteforglobalaffairs.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Caught-in-the-Middle.pdf.

Japan, South Korea, the Philippines, Australia, and Vietnam have all taken measures to address China’s rise. Since 2017, the Quad, a four-way partnership between the United States, Japan, India, and Australia, has been an important part of the region’s multilateral architecture, albeit one with unclear security relevance so far.59Dominique Fraser, “The Quad: A Backgrounder,” Asia Policy Institute, May 16, 2023, https://asiasociety.org/policy-institute/quad-backgrounder. The Quad’s previous iteration in the mid-2000s failed over conflicting views within the group about China’s power and ambitions. The Philippines has either signed defense agreements or entered into defense cooperation talks with 18 nations, the most significant of which was its 2023 decision to give the United States expanded access to four additional Filipino military bases, which inevitably drew China’s ire.60Regine Cabato, “Philippines Strikes Security Deals as Tensions Rise with China at Sea,” Washington Post, March 9, 2024, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2024/03/09/philippines-south-china-sea-security/. In January 2024, the Philippines inked a defense deal with Vietnam to improve intelligence links between their respective militaries and strengthen inter-operability between their coast guards.61Aniruddha Ghosal and Jim Gomez, “Philippines and Vietnam Agree to Expand Cooperation in South China Sea, Which Beijing Also Claims,” AP News, January 30, 2024, https://apnews.com/article/vietnam-philippines-south-china-sea-agreement-marcos-263dcb4cdbf1ca2c59c3dd1eaf04a1d1.

Japan has signed reciprocal access agreements with Australia, India, and the Philippines, permitting the Japanese Self-Defense Forces (JSDF) to visit and train with their Australian, Indian, and Philippine counterparts.62“Exchange of Diplomatic Notes for the Entry into Force of the Agreement Between the Government of Japan and the Government of the Republic of India Concerning Reciprocal Provision of Supplies and Services Between the Self-Defense Forces of Japan and the Indian Armed Forces,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, June 11, 2021, https://www.mofa.go.jp/press/release/press3e_000207.html; “Japan-Australia Reciprocal Access Agreement,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, January 6, 2022, https://www.mofa.go.jp/a_o/ocn/au/page4e_001195.html; “Signing of the Japan-Australia Reciprocal Access Agreement,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, July 8, 2024, https://www.mofa.go.jp/s_sa/sea2/ph/pageite_000001_00432.html. Japan is in discussions with Australia on an agreement that would set rules of the road between their forces during a regional emergency. Japan and India started bilateral naval exercises in 2012 and have signed an agreement on defense technology transfers. In 2017, the two countries conducted joint anti-submarine exercises in the Indian Ocean.63“Japan to Export Maritime Systems, India to Ask to Bid on P-75-I,” Indian Defence Research Wing (IDRW), December 20, 2022, https://idrw.org/japan-to-export-maritime-systems-india-to-ask-to-bid-on-p-75-i/; “Japan to Export to India Stealth Antennas Equipped on New Destroyer,” Kyodo News, October 15, 2022, https://english.kyodonews.net/news/2022/10/928878c248f3-japan-to-export-india-stealth-antennas-equipped-on-new-destroyer.html; “India, Japan Begin Three-Day Anti-Submarine Drill Amid Concerns Over China,” Business Standard, October 29, 2017, https://www.business-standard.com/article/economy-policy/india-japan-begin-three-day-anti-submarine-drill-amid-concerns-over-china-117102900541_1.html; Masahiro Kurita, “Japan-India Security Cooperation: Progress Without Drama,” Stimson, February 15, 2023, https://www.stimson.org/2023/japan-india-security-cooperation-progress-without-drama/. Japan has also significantly improved its strategic relationship with South Korea after an extended hiatus, although this is likely to come at the cost of North Korea furthering its own strategic relationships with China and Russia as a counterweight.64“Japan, Australia in Talks on Cooperation in Military Contingencies,” Kyodo News, January 15, 2024, https://english.kyodonews.net/news/2024/01/56da08dd991b-japan-australia-in-talks-on-cooperation-in-military-contingencies.html.

In response to the growth of Chinese power, India has stepped up defense cooperation with various states in the region, including Vietnam, which has a long history of conflict with China and territorial disputes in the Paracel and Spratly Islands.65Temjenmeren Ao, “India-Vietnam Defence Partnership Gaining Ground,” Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, June 26, 2023, https://idsa.in/issuebrief/india-vietnam-defence-partnership-t-ao-260623; “China Rebuts Vietnam’s Claims to Disputed South China Sea Islands,” Reuters, January 24, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/china-rebuts-vietnams-claims-disputed-south-china-sea-islands-2024-01-24/. See also Harsh V. Pant, “Looking East: India’s Growing Role in East Asian Security,” National Bureau of Asian Research, September 9, 2013, https://www.nbr.org/publication/looking-east-indias-growing-role-in-asian-security/; and Aditi Malhotra, India in the Indo-Pacific: Understanding India’s Security Orientation Towards Southeast and East Asia (Leverkusen: Verlag Barbara Budrich, 2022). In April 2023, after signing a defense contract with the Philippines, India began delivering anti-ship BrahMos supersonic cruise missiles to Manila, which can target vessels up to 180 miles from the coast.66Anjana Pasricha, “Amid China Tensions, India Delivers Supersonic Cruise Missiles to Philippines,” VOA News, April 23, 2024, https://www.voanews.com/a/amid-china-tensions-india-delivers-supersonic-cruise-missiles-to-philippines-/7581242.html. India has also increased defense-related cooperation with Australia, which included the signing in 2020 of the India-Australia Comprehensive Security Partnership.67Shubhamitra Das, “India-Australia Defence Cooperation and Collaboration in the Indo-Pacific,” Australian Institute of International Affairs, January 31, 2023, https://www.internationalaffairs.org.au/australianoutlook/india-australia-defence-cooperation-and-collaboration-in-the-indo-pacific/. These steps fall far short of alliance formation but they have the potential to transition into more robust security cooperation depending on how China’s foreign policy evolves.

China’s behavior is also driving smaller neighbors and regional powers to increase their own defense budgets and accelerate the purchase of major weapons systems. After years in which conventional platforms were prioritized, Taiwan is beginning to procure more of the anti-access and aerial denial systems (A2/AD) needed to improve its defenses against a Chinese invasion.68Eugene Gholz, Benjamin Friedman, and Enea Gjoza, “Defensive Defense: A Better Way to Protect U.S. Allies in Asia,” Washington Quarterly 42, no. 4 (2019): 171–189, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/0163660X.2019.1693103. Japan’s Defense Buildup Program, finalized in December 2022, projects to add an estimated $315 billion to Japanese defense spending by 2027. India, which is embroiled in an ongoing border dispute with China, recently completed a successful test of its Agni-5 ICBM, which can strike a target 3,100 miles away—well into Chinese territory.69Rajesh Roy, “India Adds Firepower to a Missile Program Focused on China,” Wall Street Journal, March 11, 2024, https://www.wsj.com/world/asia/india-adds-firepower-to-a-missile-program-focused-on-china-564dcd0e. Australia, meanwhile, will spend $35 billion over the next decade to build its largest navy since World War II, a development motivated in part by Chinese attempts to solidify relationships in the South Pacific, which Australia considers its backyard.70Brad Lendon, “Australia Unveils Plan for Largest Navy Buildup Since World War II,” CNN, February 20, 2024, https://www.cnn.com/2024/02/20/australia/australia-navy-buildup-intl-hnk-ml/index.html#.

In sum, Asia’s middle powers are already taking actions to counter China. This provides the United States with an opportunity to dispense with the pursuit of primacy in East Asia and prioritize offshore balancing, meaning a strategy that relies on regional powers to check the ambitions of potential threats like China.71John Mearsheimer and Stephen M. Walt, “The Case for Offshore Balancing,” Foreign Affairs, June 13, 2016, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2016-06-13/case-offshore-balancing. For a recent elaboration on an offshore balancing strategy in Asia, see Kelly A. Grieco and Jennifer Kavanagh, “America Can’t Surpass China’s Power in Asia,” Foreign Affairs, January 16, 2024, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/america-cant-surpass-chinas-power-asia/, and Kelly A. Grieco and Jennifer Kavanagh, “The Elusive Indo-Pacific Coalition: Why Geography Matters,” Washington Quarterly 47, no. 1 (2024): 103–121, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/0163660X.2024.2326324.

Shifting to a balancing approach

This section proposes ideas that can help reduce U.S. involvement in East Asia. The ideas recommended here require other states in the Asia-Pacific to assume greater responsibility for maintaining the regional balance of power. They rest on three principles: minimizing the risks of war with China, reducing U.S. burdens in East Asia, and promoting a more equitable division of labor between the United States and allies like Japan and South Korea.

The first principle involves managing U.S. relations with China and eschewing counterproductive policies that increase the likelihood of a conflict. The second requires thinning out the U.S. troop presence in the region and challenging the prevailing assumption that U.S. forward deployments must be maintained at their current level, or even increased, to prevent Chinese hegemony.

The third principle involves redistributing defense responsibilities to U.S. allies, which will serve as the first line of defense to safeguard the territorial status-quo and reduce the risks of the United States getting embroiled in regional disputes. The prerequisites for South Korea and Japan to assume a leadership role—ample resources and the willingness to do so—already exist. Japan has the world’s third largest economy and is a technological powerhouse. With respect to the Korean Peninsula, the power imbalance between South Korea and North Korea favors the former so substantially that the United States can accelerate the process of burden shifting.72“North-South Korean Elements of National Power,” Nautilus Institute for Security and Sustainability, April 27, 2011, https://nautilus.org/napsnet/napsnet-special-reports/north-south-korean-elements-of-national-power/. This enables the United States to fulfill two objectives simultaneously: maintaining a favorable balance of power in East Asia and producing capable allies rather than security dependents. To this end, the United States could negotiate multi-year agreements that commit its East Asian allies to strengthen the military capabilities that are especially important for their national defense. Or it could adopt a more coercive approach, threatening a U.S. withdrawal absent a substantially greater allied effort.

The recommendations offered are designed to start a discussion about changes to the current U.S. strategy of primacy that, in time, will lead to more cost-effective U.S. policies in East Asia.

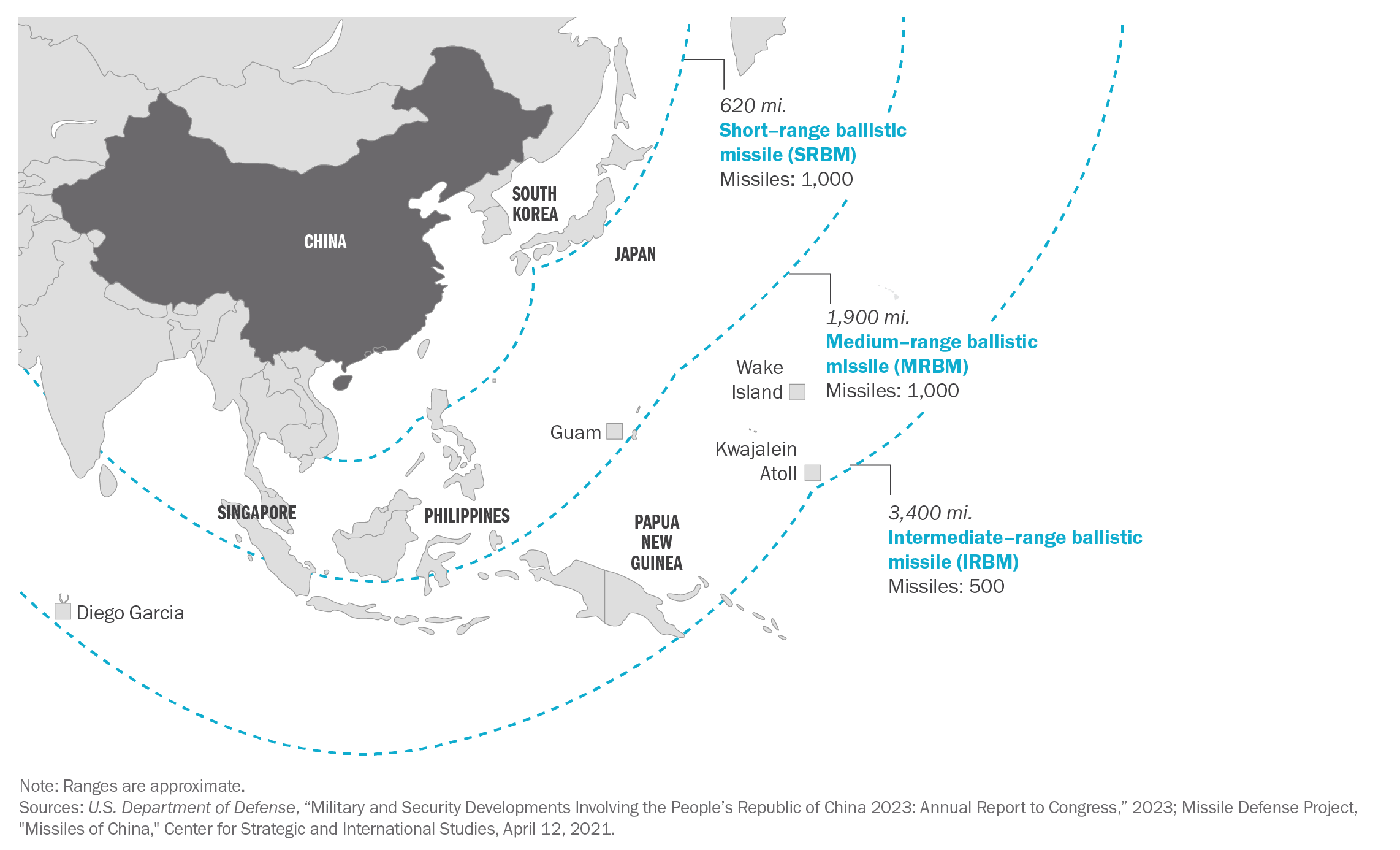

Minimize the risks of war with China

While the probability of a direct U.S.-China conflict remains low, it’s nevertheless a high-impact scenario. In the event of a war, China’s growing military might will lead to a massive loss of life on the U.S. side. U.S. military facilities such as the Kadena Air Base in Japan, where 23,000 personnel are stationed, and Camp Humphreys in South Korea are already within range of Chinese intermediate-range ballistic missiles.73“Kadena Air Base,” Pacific Air Forces, United States Air Force, October 20, 2021, https://www.pacaf.af.mil/Info/Fact-Sheets/Display/Article/909901/kadena-air-base/. Even if China’s economic growth slows, its material resources will keep increasing, ensuring that a Sino-American war will become ever more deadly. China may not be able to use anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) to prevent U.S. forces from operating within the Second Island Chain, but its armed forces have the capacity to impose a crippling blockade on Taiwan, which is much closer to the Chinese mainland.

Chinese ballistic missile ranges

China’s growing economic, technological, and military capabilities will require the United States to take more risks and incur increasing costs in blood and treasure to project and sustain its forces in East Asia.74Grieco and Kavanagh, “America Can’t Surpass China’s Power in Asia.” The tyranny of distance and military modernization (the greater speed, accuracy, and survivability of missiles in particular) will give China significant advantages in wartime, even if the U.S. were to prevail in the end.75Maximilian K. Bremer and Kelly A. Greico, “The Four Tyrannies of Logistical Deterrence,” Stimson, November 8, 2023, https://www.stimson.org/2023/the-four-tyrannies-of-logistical-deterrence/#:~:text=Tyranny%20of%20Distance&text=Taiwan%20is%20located%20100%20miles,Europe%20during%20the%20Cold%20War. This alone requires that U.S. grand strategy in Asia be guided by the assumption that a war with China must be fought only when vital U.S. national security interests are at stake.

Even then, the United States must balance the need to defend its core interests with the highly destabilizing impacts a war would have. A conventional war with China could escalate rapidly—and even uncontrollably. Both the United States and China may wish to confine themselves to using conventional weapons, but misperception, worst-case thinking, or a desperation to avoid losing—all of which can loom large during conflicts—could lead to the use of nuclear weapons by either side. While some may discount the possibility of nuclear war, U.S. leaders would be derelict in their duty if they did the same. China is likely to regard a conflict with the United States, particularly over Taiwan, as an existential one that necessitates using the full range of China’s military capabilities.76Notwithstanding China’s decades-old, no first use policy when it comes to nuclear weapons, Chinese military documents leave open the possibility of departing from it if required to avoid defeat in a high-stakes conventional war. See Keir A. Lieber and Daryl G. Press, “The Return of Nuclear Escalation,” Foreign Affairs, October 24, 2023, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/return-nuclear-escalation.

Third, a U.S.-China war in East Asia could also lead to “horizontal escalation.” China might decide that, as a matter of self-defense, it cannot limit itself to striking U.S. naval forces projected off its eastern coastline and choose to target U.S. bases that could sustain U.S. military activity, especially those in Japan and South Korea. This, in turn, would confront Japan and South Korea with an unappealing choice: join the United States in a war with China, or bar the United States from using bases on their soil to attack China in an attempt to wall themselves off from Chinese retaliation.

Fortunately, a Chinese invasion is by no means certain. While the PLA’s military modernization is indisputable, it lacks the overseas basing network, at-sea replenishment ships, and aircraft carrier capacity to project power beyond the First Island Chain over a long period of time.77Mike Sweeney, “Challenges to Chinese Blue-Water Operations,” Defense Priorities, April 30, 2024, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/challenges-to-chinese-blue-water-operations/. Moreover, China’s economic growth has been slowing.78Jason Douglas, “What’s Wrong with China’s Economy, in Eight Charts,” Wall Street Journal, March 1, 2024, https://www.wsj.com/world/china/whats-wrong-with-chinas-economy-in-eight-charts-efc2ea5f; Chris Anstey, “China’s Debt Mountain Is Even Bigger Than Feared,” Bloomberg, January 6, 2024, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/newsletters/2024-01-06/bloomberg-new-economy-china-s-debt-mountain-is-even-bigger-than-feared. A war with the United States would make matters much worse.

Even so, the triggers for escalation—including differing perceptions on the East Asian political and economic order, the U.S. determination to maintain primacy, and China’s aspirations to challenge that primacy—are present and will likely become even more prominent. Although tensions in the U.S.-China relationship are highly unlikely to be fully resolved, several commonsense recommendations can help mitigate them:

- Given the growing animosity between China and the United States as well as the increasing number of close encounters between U.S. and Chinese military aircraft in the vicinity of Taiwan, military-to-military communications between both countries should become routine so as to minimize the chances of misperception and escalation. In parallel, the two countries should implement crisis management and confidence-building measures designed to reduce the likelihood of a collision between their ships and planes in and around the Taiwan Strait and elsewhere. Even better, the United States should reduce its military presence along China’s periphery and limit, if not suspend, patrols in the Taiwan Strait, which needlessly antagonize China for no discernable gain.

- The United States should be more cognizant of how deploying offensive weapons systems, in particular long-range missiles, near China’s periphery could exacerbate the security dilemma, encourage worst-case thinking, and even invite preventive war. Offensive weapons, particularly if they can reach strategic targets deep inside mainland China—command-and-control facilities, ICBM silos, and installations related to China’s nuclear weapons apparatus, just to name a few—ultimately promote instability by encouraging an arms race between the United States and China and increasing the prospects of either country striking first during a crisis.79M. Taylor Fravel and Eric Heginbotham, “Envisioning a Stable Military Balance in 2034,” in U.S.-China Relations for the 2030s: Toward a Realistic Scenario for Coexistence, ed. Christopher S. Chivvis (Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2024): 79–90, https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2024/10/us-china-relations-for-the-2030s-toward-a-realistic-scenario-for-coexistence#envisioning-a-stable-military-balance-in-2034. The United States should therefore minimize the deployment of long-range missiles to East Asia or at the very least ensure existing deployments are temporary.

- The United States should refrain from rhetoric and policies aimed at undermining China’s political system. It is beyond U.S. capacity to achieve successful social engineering in large, complex societies such as China’s, and our record in achieving such transformations in other areas of the world—in particular the Middle East—should make us especially leery. Making democracy promotion or regime change an element of U.S. strategy will only deepen China’s suspicion that the United States seeks to destroy the CCP, decreasing the likelihood that the Sino-American rivalry can be managed.

- The 1979 Taiwan Relations Act obligates the United States to provide Taiwan with the means for its self-defense until such time that Beijing and Taipei agree on a path to peaceful reunification. The United States should stick to the letter of the law and avoid actions—diplomatic and military—that would suggest the U.S. military would assume responsibility for defending Taiwan. Creeping toward a formal defense commitment to Taiwan or transitioning to “strategic clarity” will increase the likelihood of war with China by crossing Beijing’s red line on a matter it deems a vital interest.80Ken Moriyasu, “More U.S. ‘Clarity’ on Taiwan Policy Needed, Ex-Commander Says,” Nikkei Asia, June 7, 2024, https://asia.nikkei.com/Editor-s-Picks/Interview/More-U.S.-clarity-on-Taiwan-policy-needed-ex-commander-says.

- The United States should protect itself from unfair Chinese trade practices and limit Chinese investment in industries with clear military applications. But it should also eschew aggressive protectionist policies that segue into economic warfare. These include blanket bans on Chinese investments, sweeping prohibitions on American companies’ investments in China, and open-ended measures that go beyond economic necessity designed to damage the Chinese economy as an end in itself. China’s economy has become so large and advanced that the pain resulting from economic warfare would not be a one-way affair. Moreover, without the cooperation of other major economies, a strategy of squeezing the Chinese economy will not work, and Europe, Japan, and South Korea have too much to lose to join such an effort.

Rebalance the U.S.-South Korean relationship

The United States has substantially reduced its troop presence in South Korea over time—from a post-Korean War high of 75,000 to around 28,500 today—and removed nuclear weapons after the Cold War.81Clint Work, “What’s in a Tripwire: The Post-Cold War Transformation of the US Military Presence in Korea,” Stimson, June 9, 2022, https://www.stimson.org/2022/whats-in-a-tripwire-the-post-cold-war-transformation-of-the-us-military-presence-in-korea/. But the top U.S. objective on the Korean Peninsula remains the same as when the alliance was first established: to deter and, if necessary, defeat a North Korean attack. That objective is the basis of the 1953 Mutual Defense Treaty, which states that an armed attack against U.S. or South Korean territories in the Pacific region would warrant collective action in line with each state’s constitutional processes.82“Mutual Defense Treaty Between the United States and the Republic of Korea,” accessed through United States Forces Korea, October 1, 1953, https://www.usfk.mil/Portals/105/Documents/SOFA/H_Mutual%20Defense%20Treaty_1953.pdf.

Some former U.S. officials aim to enlist South Korea into U.S. containment efforts against China, either by encouraging South Korea to be more vocal in denouncing Chinese intimidation of Taiwan or incorporating the South Korean military into U.S. contingency planning for a possible war in East Asia.83Christy Lee, “Former US Commander in Korea Urges Allies to Include China in War Plans,” Voice of America, January 11, 2022, https://www.voanews.com/a/former-top-us-commander-in-korea-urges-allies-to-include-china-in-war-plans/6391856.html. Yet those efforts are unlikely to bear fruit for a number of reasons—South Korea is wary of rupturing or at least jeopardizing relations with China, its largest trading partner; there is no political consensus in South Korea for a radical shift in China policy that involves containing China; and notwithstanding its alliance with the United States, Seoul wants to avoid choosing between the region’s two predominant powers in order to prevent being dragged into a U.S.-China war.84Jessica J. Lee and Sarang Shidore, “The Folly of Pushing South Korea Toward a China Containment Strategy,” Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft, May 5, 2022, https://quincyinst.org/research/the-folly-of-pushing-south-korea-toward-a-china-containment-strategy/#executive-summary.

With respect to the Korean Peninsula specifically, South Korea’s economic, technological, and military power is now adequate to deter North Korea from launching a war and to ensure that it pays a steep price if it initiates an armed confrontation. Although some argue this task is complicated by North Korea’s nuclear weapons program and the greater range of its missile inventory, deterrence has been maintained for decades and will continue to be maintained once South Korea takes the lead. Even with a more peripheral U.S. role, North Korea likely assumes the United States would assist South Korea in some capacity if Pyongyang initiated a conventional or nuclear strike. That a large-scale North Korean conventional attack below the 38th parallel has not come to pass is not a surprise; the Kim dynasty understands that going to war against South Korea could precipitate its own destruction.85It should be noted that skirmishes between the two Koreas have occurred, most notably in 2010 when the Kim dynasty torpedoed the South Korean navy corvette Cheonan in the disputed Yellow Sea and shelled Yeonpyeong Island.

During the first three decades of the Cold War, the balance of power on the Korean Peninsula was more favorable to North Korea. In 1970, Pyongyang’s economy was roughly comparable to Seoul’s, North Korea drew economic and military support from two patrons (China and the Soviet Union), and South Korea was experiencing periodic political turmoil.86Brad Plumer, “Kim Jong II’s Economic Legacy, in One Chart,” Washington Post, December 19, 2011, https://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/ezra-klein/post/the-economic-legacy-of-kim-jong-il/2011/12/19/gIQA4osP4O_blog.html. This is no longer true. North Korea’s economy, which stagnated in the 1970s, shrunk even further after the collapse of the Soviet Union. North Korean leader Kim Jong-un has admitted in official speeches that Pyongyang’s economic outlook is grim.87Lee Jeong-Ho, “Kim Jong Un Acknowledges Dire State of Economy, Urges Action,” Radio Free Asia, January 24, 2024, https://www.rfa.org/english/news/korea/nk-economy-warn-01242024213121.html. The 2024 comprehensive strategic partnership agreement between Russia and North Korea could ameliorate these economic troubles to a certain extent, although exactly how much remains to be determined. In contrast, South Korea has established itself as a leading economic and technological power, with a gross national income 60 times that of its adversary.88“Korea and the OECD,” Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), accessed July 14, 2024, https://www.oecd.org/country/korea/thematic-focus/a-global-powerhouse-in-science-and-technology-61cbd1ad/; Leigh Dayton, “How South Korea Made Itself a Global Innovation Leader,” Nature, May 27, 2020, https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-01466-7; “Gross Domestic Product Estimates for North Korea in 2023,” Bank of Korea, https://www.bok.or.kr/eng/bbs/E0000634/view.do?nttId=10086116&searchCnd=1&searchKwd=&depth2=400417&depth3=400423&depth=400423&pageUnit=10&pageIndex=1&programType=newsDataEng&menuNo=400423&oldMenuNo=400423. North Korea’s roughly $4 billion defense budget is less than one-tenth of what South Korea spends in any given year.89Chung Min Lee, “The Hollowing Out of Kim Jong Un’s North Korea,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, April 29, 2024, https://carnegieendowment.org/2024/04/29/hollowing-out-of-kim-jong-un-s-north-korea-pub-92302.

Although South Korea lacks nuclear weapons, it remains under the U.S. nuclear umbrella. It’s equipped with state-of-the-art weaponry, has access to advanced U.S. defense equipment—including F-35 joint strike fighter aircraft—and sustains an impressive defense industrial base.90Wooyeal Paik, South Korea’s Emergence as a Defense Industrial Powerhouse (Paris: French Institute of International Relations, 2024) https://www.ifri.org/sites/default/files/migrated_files/documents/atoms/files/ifri_paik_south_korea_defense_2024.pdf; Gordon Arthur, “How South Korea’s Defense Industry Transformed Itself into a Global Player,” Breaking Defense, November 6, 2023, https://breakingdefense.com/2023/11/how-south-koreas-defense-industry-transformed-itself-into-a-global-player/; “Korea – F-35 Aircraft,” Defense Security Cooperation Agency, September 13, 2023, https://www.dsca.mil/press-media/major-arms-sales/korea-f-35-aircraft. Unlike North Korean ground forces, which are often called upon to perform menial labor tasks, the South Korean military is combat ready due to constant training and military exercises with both the United States and Japan. The South Korean government is projected to spend $262 billion on defense in the 2024–2028 timeframe, a sum that will pay for the procurement of reconnaissance satellites, submarines, and surface-to-air missile systems.91Chae Yun-hwan, “S. Korea Seeks to Spend Nearly 350 tln Won in Defense over Next 5 Years,” Yonhap News Agency, December 12, 2023, https://en.yna.co.kr/view/AEN20231212004151315.

This is not to say that North Korea doesn’t pose a threat to South Korea or the U.S. forces deployed there. In March 2023, North Korea launched two cruise missiles from a submarine that military experts believe could strike U.S. bases in South Korea and Okinawa, Japan.92Ellen Kim, “North Korea Launches Strategic Cruise Missiles from Submarine,” Center for Strategic International Studies (CSIS), March 13, 2023, https://www.csis.org/analysis/north-korea-launches-strategic-cruise-missiles-submarine. In December 2023, Pyongyang test-fired a solid-fueled intercontinental ballistic missile, a system that could target the continental United States more expeditiously than a liquid-fueled variant.93Hyung-Jin Kim and Mari Yamaguchi, “North Korea Conducts First Long-Range Missile Test in Months, Likely Firing a Solid-Fueled Weapon,” AP News, December 18, 2023, https://apnews.com/article/north-korea-missile-launch-bc0391e981b2eedce5dc17734e27ee0c. North Korean artillery can easily reach Seoul, a city of nearly 10 million people, putting the South Korean capital city—which is only 35 miles away from the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ)—at risk of destruction if hostilities commenced. Such proximity, however, also contributes to deterrence by restraining South Korea from any preventive military action against North Korea.

North Korea’s nuclear and missile programs seek to compensate for its Cold War-era vintage conventional forces. Pyongyang’s quantitative superiority in tanks is vastly outweighed by its qualitative inferiority. Most North Korean artillery systems were procured before 1990, which raises the question of how reliable they would be in a wartime scenario.94Lee, “The Hollowing Out.” North Korea’s air force is stocked with aircraft from the 1950s and 1960s, hobbled by readiness issues and insufficient training, and plagued by a shortage of spare parts.95Haena Jo, “Flying Against the Odds: North Korea’s Air Force,” International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS), February 10, 2020, https://www.iiss.org/en/online-analysis/military-balance/2020/02/north-korea-air-force/.

Pyongyang’s signing in June 2024 of a comprehensive strategic partnership agreement with Russia, which includes defense cooperation between the two powers, will not necessarily change the balance of forces.96“DPRK-Russia Treaty on Comprehensive Strategic Partnership,” KCNA Watch, June 20, 2024 https://kcnawatch.org/newstream/1718870859-459880358/dprk-russia-treaty-on-comprehensive-strategic-partnership/. Russia gets munitions it needs for its war in Ukraine, and North Korea gets some satellite technology and food supplies. Pyongyang’s strategic relationship with China, forged in the early days of the Cold War, is likewise less than meets the eye: the North Korean political and military leadership is suspicious of its much larger neighbor. Notwithstanding the 1961 Treaty of Friendship, China is unlikely to intervene militarily in support of North Korea unless it is necessary to prevent a U.S. military presence along the Chinese border.97“Treaty of Friendship, Co-operation and Mutual Assistance Between the People’s Republic of China and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea,” Peking Review 4, no. 28 (1961); Simon Denyer and Amanda Erickson, “Beijing Warns Pyongyang: You’re on Your Own If You Go After the United States,” Washington Post, August 11, 2017, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/china-warns-north-korea-youre-on-your-own-if-you-go-after-the-us/2017/08/11/a01a4396-7e68-11e7-9026-4a0a64977c92_story.html.

In short, although it may have been appropriate for the United States to assume an outsize role in South Korea’s defense following the Korean War, the balance of power on the Korean Peninsula has changed dramatically since then. South Korea has a massive advantage even without U.S. help.98Korean Net Assessment: Politicized Security and Unchanging Strategic Realities, Chung Min Lee and Kathyrn Botto, eds. (Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2020) https://carnegieendowment.org/2020/03/18/state-of-north-korean-military-pub-81232. U.S. policy needs to catch up with this reality:

- The U.S.-South Korea alliance should be re-oriented so that Seoul takes primary responsibility for its own security. Even though South Korea has the world’s eleventh largest economy and eleventh largest defense budget, its armed forces would still be under the command of the United States in the event of a war.99Nan Tian et al., “Trends in World Military Expenditure, 2023,” Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), April 2024, https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/2024-04/2404_fs_milex_2023.pdf; Rajan Menon, “5 Things South Korea Can Do to Wrest Control from Washington,” National Interest, December 21, 2017, https://nationalinterest.org/feature/5-things-south-korea-can-do-wrest-control-washington-23736. This arrangement was justified in the years after the Korean War, when South Korea was trying to repair its economy and rebuild its military; it is no longer appropriate. Instead, the United States should accelerate the transition of operational control (OPCON) of South Korean forces back to the South Korean military, regardless of political resistance in Seoul.100Soo Kim, “U.S.-South Korea OPCON Transition: The Element of Timing,” RAND Corporation, April 2, 2020, https://www.rand.org/pubs/commentary/2020/04/us-south-korea-opcon-transition-the-element-of-timing.html. Today, OPCON transfer is conditioned on South Korea meeting several military benchmarks, including the possession of sufficient military capabilities and mastering combat leadership at all levels of the military hierarchy. Concerns about whether South Korea has enough ISR assets have consistently slowed the transition but can be addressed by the United States in future defense sales to Seoul. Waiting for the perfect strategic environment on the Korean Peninsula to emerge before finalizing OPCON transfer will result in perpetual delay.101Clint Work, “No More Delays: Why It’s Time to Move Forward with Wartime OPCON Transition,” 38 North, June 21, 2022, https://www.38north.org/reports/2022/06/no-more-delays-why-its-time-to-move-forward-with-wartime-opcon-transition/.

- The current U.S. force posture in South Korea is outdated thanks to rising South Korean military power.102Doug Bandow, “Even with Seoul Paying More, America Can’t Afford to Defend South Korea,” Foreign Policy, April 12, 2021, https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/04/12/us-south-korea-military-spending-sma/. The United States should take advantage of this by scaling down its troop presence in South Korea—most of which is confined to large bases that would be targets for North Korean missile attacks.

- The United States should be more realistic about what it expects of North Korea on the issue of nuclear weapons. Multiple U.S. administrations have linked improvement of U.S.-North Korea relations to Pyongyang eliminating its nuclear infrastructure. North Korea will never accept such terms because it depends on nuclear weapons for its survival. The benefits of a U.S. normalization of relations, economic sanctions relief, and a formal end to the Korean War wouldn’t sufficiently compensate North Korea for the loss of nuclear weapons. Instead of pressing for denuclearization, the United States should adopt several commonsense reforms to U.S. policy. These include establishing confidence-building and risk-reduction measures with North Korea, reiterating to the Kim dynasty that regime change is not U.S. policy, and exploring a new diplomatic process whereby incremental North Korean concessions—a freeze on intermediate or ICBM tests, the suspension of nuclear tests, re-entering the 2018 Comprehensive Military Agreement, an inter-Korean military de-escalation accord—are met with incremental U.S. concessions like formal diplomatic relations, a phased lifting of sanctions and export controls, and U.S. troop reductions in South Korea.

Devolve more responsibility to Japan

Japan’s long history of military aggression and its constitutional provision against military operations that go beyond self-defense have long been obstacles to its taking on more of the security burden in East Asia. However, Japan has already changed considerably on this front and laid the groundwork for doing more to provide for its defense. The United States should enable this trend by reducing U.S. defense efforts in the region, encouraging the Japanese to step up.

Since World War II, Japan has adhered to what might be called military minimalism: the Japan Self-Defense Forces (JSDF) remained small and lacked the capacity to project power far afield as well as the weapons capable of striking distant targets. Annual defense spending never exceeded 1.1 percent of GDP between 1960 and 2021 and in many years was even lower.103“Military Expenditure (% of GDP) – Japan,” World Bank Group, accessed July 14, 2024, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/MS.MIL.XPND.GD.ZS?locations=JP.

Japan’s neighbors, including China, Korea, and the Philippines, which suffered grievously at the hands of Imperial Japan’s army, harbored a deep-seated fear of Japanese rearmament. Japan was also able to maintain a small army because it could entrust its security to the United States under the terms of the 1951 defense treaty, which was revised in 1960 to give Japan more agency.104“Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security Between the United States of America and Japan,” accessed through the Weatherhead East Asian Institute at Columbia University, January 19, 1960, http://afe.easia.columbia.edu/ps/japan/mutual_cooperation_treaty.pdf.

Still, as its internal and external circumstances have changed, in particular China’s increasing power, so have the capabilities and missions of the JSDF—albeit slowly.105Jennifer Lind, “Japan’s Security Evolution,” Cato Institute, September 25, 2016, https://www.cato.org/policy-analysis/japans-security-evolution; Jeffrey Hornung “Japan’s Play for Today: Too Much, Just Right, or Never Enough,” War on the Rocks, October 31, 2023, https://warontherocks.com/2023/10/japans-play-for-today-too-much-just-right-or-never-enough/. Starting in the late 1970s, Japan bolstered its navy and air force. In 1978, under the terms of the revised guidelines for defense cooperation with the United States, the JSDF expanded its mission from defending the homeland with U.S. assistance to helping maintain peace in East Asia. In 1981, Japan, encouraged by the United States, undertook to patrol the sealines out to 1,000 nautical miles from its mainland.106Joseph F. Bouchard and Douglas J. Hess, “The Japanese Navy and Sea-Lanes Defensive,” Proceedings, March 1984, https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/1984/march/japanese-navy-and-sea-lanes-defense.

In 2014, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, in what amounted to a reinterpretation of the Japanese constitution, decided that collective defense involving assistance to an ally under attack was legal, provided Japanese lives were at stake, the necessary amount of force was used, and no other defensive means were available.107The Constitution of Japan, accessed through the Prime Minister of Japan and his Cabinet, November 3, 1946, https://japan.kantei.go.jp/constitution_and_government_of_japan/constitution_e.html. This change expanded the JSDF’s mission beyond defending Japan’s home islands.108“Abe’s Moves Toward Collective Self-Defense,” Nippon, July 11, 2014, https://www.nippon.com/en/features/h00062/.

Yet these changes pale in comparison to those announced in December 2022 with the publication of three important documents: the National Security Strategy, the National Defense Strategy, and the Defense Buildup Program.109“National Security Strategy (NSS),” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, accessed July 14, 2024, https://www.mofa.go.jp/fp/nsp/page1we_000081.html; “National Defense Strategy,” Ministry of Defense of Japan, December 16, 2022, https://www.mod.go.jp/j/policy/agenda/guideline/strategy/pdf/strategy_en.pdf; “Defense Buildup Program,” Ministry of Defense of Japan, December 15, 2022, https://www.mod.go.jp/j/policy/agenda/guideline/plan/pdf/program_en.pdf. Taken together, they commit Japan to making unprecedented changes to its defense policy. Within the confines of its alliance with the United States, Japan now aims to take “primary responsibility” for disrupting and defeating an invasion of its territory.

To this end, Japan’s defense budget in 2024 was more than $56 billion, a 20 percent increase since 2014.110Shinnosuke Nagatomi, “Japan’s Defense Spending Climbs to 1.6% of GDP,” Nikkei Asia, August 27, 2024, https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/Defense/Japan-s-defense-spending-climbs-to-1.6-of-GDP. For a year-by-year comparison of Japan’s defense spending, consult the SIPRI Military Expenditure database. Japan plans to increase its defense spending to 2 percent of its GDP by 2027, and acquire a range of weapons capable of striking the military assets and territory of attackers. The arms envisaged include air-to-surface, surface-to-surface, and air defense missiles; sixth-generation fighter jets; surface, air, and underwater drones; and hypersonic glide vehicles. These “counterstrike” armaments will be complemented by state-of-the-art capabilities in cyberwarfare, satellite surveillance, missile defense, and electronic countermeasures.111Yoshihiro Inaba, “Japan Doubles Down on Standoff Missiles to Deter China,” Naval News, May 15, 2023, https://www.navalnews.com/naval-news/2023/05/japan-doubles-down-on-standoff-missiles-to-deter-china/; Kapil Kajal, “Japan Progresses Hypersonic and Long-Range Missile Programmes,” Janes, April 12, 2023, https://www.janes.com/osint-insights/defence-news/defence/japan-progresses-hypersonic-and-long-range-missile-programmes; Takahashi Kosuke, “Japan Awards Kawasaki Heavy Industries $243 Million Contract for Homegrown Version of Tomahawk Missile,” Diplomat, June 7, 2023, https://thediplomat.com/2023/06/japan-awards-kawasaki-heavy-industries-243-million-contract-for-homegrown-version-of-tomahawk-missile/. Japan has much more to do if it wants to move toward greater military self-sufficiency, but its recent initiatives represent a break with the past and will likely continue as the threat from China increases and the risks associated with defending Japan increase for the United States.

Given Japan’s imperial history in Asia, its neighbors will watch these changes warily. But the bottom line is that Japan can do more on the defense front while avoiding past mistakes. The United States’ pursuit of primacy is in some ways an effort against Japan completing this shift, preventing it from more energetically balancing Chinese power. That needs to change, and can through the following steps: