March 18, 2025

Grand strategy: The limits of military force

This explainer is part of the series "Grand Strategy Explained"

Key points

- Since the Cold War, the United States has engaged in a number of military conflicts abroad, yet despite its preponderant military power, it has been unable to translate force into political success, especially when it comes to nation-building.

- In the absence of another great power to constrain it, the United States initiated regime change wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, but by the same token it lacked an external imperative to devote the resources needed to achieve its ambitious nation-building goals. As costs and casualties mounted, public opinion soured.

- Policymakers thought U.S. technological superiority would keep casualties in these conflicts low and the attractiveness of liberal values would make nation-building easier. They underestimated how much coercive power would be needed on the ground to maintain order and the popular consent necessary for legitimate governments to emerge.

- Later attempts to intervene abroad with limited or no boots on the ground, as in Libya and Syria, were similarly unsuccessful, leaving vacuums of power, failed states, and long-term civil wars.

- Policymakers need to become more sober about the limits of military power. The United States’ abundant security means that it would benefit from more diplomacy and deal-making with adversaries, rather than threatening to overthrow or sanction their regimes.

The United States’ post-Cold War grand strategy of “liberal hegemony” sought to exercise and expand U.S. military dominance in order to reshape the world according to Washington policymakers’ preferences. Frequently, those preferences have had less to do with threats to U.S. security than with ideological projects for regime change and nation-building in far-flung parts of the world. This grand strategy has proven to be disastrous, wasting the sources of the United States’ strength, overextending its military and financial resources, and provoking or creating new adversaries, all while failing to achieve its professed goals. Nonetheless, the lure of primacy continues to exercise a powerful grip on the minds of U.S. policymakers.

When reviewing the United States’ post-Cold War foreign policy, therefore, two puzzling and interrelated questions arise. First, why was the abundantly secure United States, which faced no peer competitor during the “unipolar moment,” in a near-constant state of war? Second, given its unmatched power position, why did the United States fail so frequently to achieve its desired outcomes or to subdue far weaker foes?

This paper attempts to provide answers to those questions so that similar blunders might be avoided in the future. In the absence of the external check imposed by the Soviet Union, the United States became emboldened to use its military power without reserve, making hubristic assumptions about its ability to translate military means into desired political ends. The more ambitious those ends, the more exorbitant the demands on resources—yet the less vital those ends, the less those demands on the requisite means can be domestically sustained.

As a result, the United States has repeatedly gotten bogged down in costly occupations, or has left behind failed and fractured states wracked by civil war. Avoiding blunders of this kind in the future will require policymakers to have a more modest and sober assessment of U.S. interests, exercise skepticism of the usefulness of military intervention, and be more willing to engage in diplomacy when disputes arise.

The ‘unipolar moment’

In the eight decades since the end of World War II, there has been an absence of major wars between great powers—a fortunate and historically unusual circumstance. Realists tend to attribute this long “great power peace” to two major causes: the invention of nuclear weapons and the distribution of power during this period.

The invention of nuclear weapons has contributed to great power peace because it raises the potential costs of war between nuclear powers far beyond the plausible benefits of aggression, making deliberate conventional war between states with second-strike nuclear capabilities almost unimaginable.1Robert Jervis, The Meaning of the Nuclear Revolution: Statecraft and the Prospect of Armageddon (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1989). Nuclear weapons likely played the key role in compelling the leaders of the United States and the Soviet Union to keep the Cold War “cold.”

The international distribution of power since World War II also contributed to great power peace due to the number of great powers in—or the “polarity” of—the international system. While the international system during the first half of the twentieth century was “multipolar” (characterized by multiple great power competitors), after World War II and throughout the Cold War it was “bipolar.” As Kenneth Waltz wrote during the height of the Cold War, bipolarity produces stability by simplifying the strategic calculus of the great powers, minimizing independent centers of decision-making, and reducing the salience of accruing additional increments of power through restlessly shifting alliances.2Kenneth N. Waltz, “The Stability of a Bipolar World,” Daedalus 93, no. 3 (Summer, 1964): 881–909; Kenneth N. Waltz, Theory of International Politics (Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press, 1979), 170–176.

The collapse of the Soviet Union made the world “unipolar,” leaving the United States as the only great power. Unipolarity eliminates the threat of great power war by definition, but it does not necessarily result in peace tout court. After the Cold War, some believed that unipolarity would be the most stable and peaceful condition of all, relieving the “unipole” of the imperatives for security competition and conflict.3William C. Wohlforth, “The Stability of a Unipolar World,” International Security 24, no. 1 (Summer, 1999): 5–41; Michael Mastanduno, “Preserving the Unipolar Moment: Realist Theories and U.S. Grand Strategy After the Cold War,” International Security 21, no. 4 (Spring, 1997): 49–88. Many realists, however, foresaw at the time that in the absence of external constraints imposed by a countervailing source of power, the unipole would be undeterred from pursuing its preferences through force, especially against weaker states—should it choose to do so.4Kenneth N. Waltz, “Structural Realism After the Cold War,” International Security 25, no. 1 (Summer 2000): 5–41; Robert Jervis, “Unipolarity: A Structural Perspective,” World Politics 61, no. 1 (January 2009): 188–213; Nuno P. Monteiro, “Unrest Assured: Why Unipolarity is Not Peaceful,” International Security 36, no. 3 (Winter 2011/2012): 9–40. Moreover, realists predicted that a dominant power, when not checked from without, is unlikely to exercise prudence, and by expending its resources carelessly through war, will accelerate its own relative decline as new powers inevitably emerge.5Christopher Layne, “The Unipolar Illusion: Why New Powers Will Rise,” International Security 17, no. 4 (Spring, 1991): 5–51; Kenneth N. Waltz, “The Emerging Structure of International Politics,” International Security 18, no. 2 (Fall 1993): 44–79.

During the unipolar moment, the United States was in the enviable position of possessing a surplus of power far beyond what was needed to maintain its core security—its sovereignty, territory, population, and the reproduction of its relative power position.6I borrow this criterion from Barry R. Posen, Restraint: A New Foundation for U.S. Grand Strategy (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2014), 1–3. While one might think that the end of the Cold War would have allowed the United States to go home and enjoy the long-promised “peace dividend,” in the decades which followed it expanded its foreign commitments while initiating a conspicuous number of military interventions far afield.7Sidita Kushi and Monica Duffy Toft, “Introducing the Military Intervention Project: A New Dataset on US Military Interventions, 1776-2019,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 67, no. 4 (April 2023): 752–779; Barbara Salazar Torreon and Sofia Plagakis, “Instances of Use of United States Armed Forces Abroad, 1798–2023,” Congressional Research Service, June 7, 2023, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R42738/41; Jennifer Kavanagh, et al., Characteristics of Successful U.S. Interventions (Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 2019), https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR3062.html.

Many U.S. policymakers and analysts came to believe the unipolar moment provided a unique opportunity to reshape the world according to Washington’s preferences and permanently sustain American primacy.8“Excerpts From Pentagon’s Plan: ‘Prevent the Re-Emergence of a New Rival’,” New York Times, March 8, 1992, https://www.nytimes.com/1992/03/08/world/excerpts-from-pentagon-s-plan-prevent-the-re-emergence-of-a-new-rival.html; James Mann, Rise of the Vulcans: The History of Bush’s War Cabinet (New York: Viking, 2004), 198–215. Also see the influential article by Charles Krauthammer, “The Unipolar Moment,” Foreign Affairs 70, no. 1 (1990/1991): 23–33. As Secretary of State Madeleine Albright said to a skeptical Colin Powell when debating the wisdom of a U.S. intervention in Bosnia in 1993, “What’s the point of having this superb military that you’re always talking about if we can’t use it?”9Quoted in Christopher A. Preble, The Power Problem: How American Military Dominance Makes Us Less Safe, Less Prosperous, and Less Free (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2009), 4. Especially following the attacks of 9/11, the United States embarked on a global mission to overthrow regimes it didn’t like and install Western-friendly liberal democracies in their place, believing this would pacify the international environment.10This is the main topic of John J. Mearsheimer, The Great Delusion: Liberal Dreams and International Realities (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2018). For examples of “militant liberalism,” see Bill Clinton, “Address to a Joint Session of Congress on the State of the Union,” U.S. Government Publishing Office, January 25, 1994, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/WCPD-1994-01-31/pdf/WCPD-1994-01-31-Pg148.pdf; Bill Clinton, “Address to a Joint Session of Congress on the State of the Union,” American Presidency Project, January 24, 1995, https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/address-before-joint-session-the-congress-the-state-the-union-11; George W. Bush, “Address to a Joint Session of Congress on the State of the Union,” White House, January 9, 2002, https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/news/releases/2002/01/20020129-11.html; William Kristol and Robert Kagan, “Toward a Neo-Reaganite Foreign Policy,” Foreign Affairs 75, no. 4 (July-Aug., 1996): 18–34.

Despite its overwhelming military superiority, however, the United States has repeatedly been unable to translate its military power into political success. While the United States has been able to overthrow regimes without too much difficulty, it has been unable to maintain or install more pliant governments in their place and go home. Instead, it has repeatedly gotten bogged down in costly occupations fighting implacable insurgencies, or has left behind failed or fractured states.

The paradox of U.S. primacy

The reasons why the United States has been so cavalier with the use of force since the end of the Cold War, on the one hand, and why those interventions have so often proven to be failures, on the other, are in fact interrelated. While the United States’ abundant power allows it to initiate wars, its concomitant security means these wars are highly elective since there is no vital threat posed.11This overlaps with the main thesis of Preble, The Power Problem. Also see Stephen M. Walt, “The Intervention Paradox,” Foreign Policy, April 20, 2011, https://foreignpolicy.com/2011/04/20/the-intervention-paradox/. Minor interests mean the public will have a low tolerance for costs devoted to the war, and support is likely to decrease over time, particularly as casualties mount.

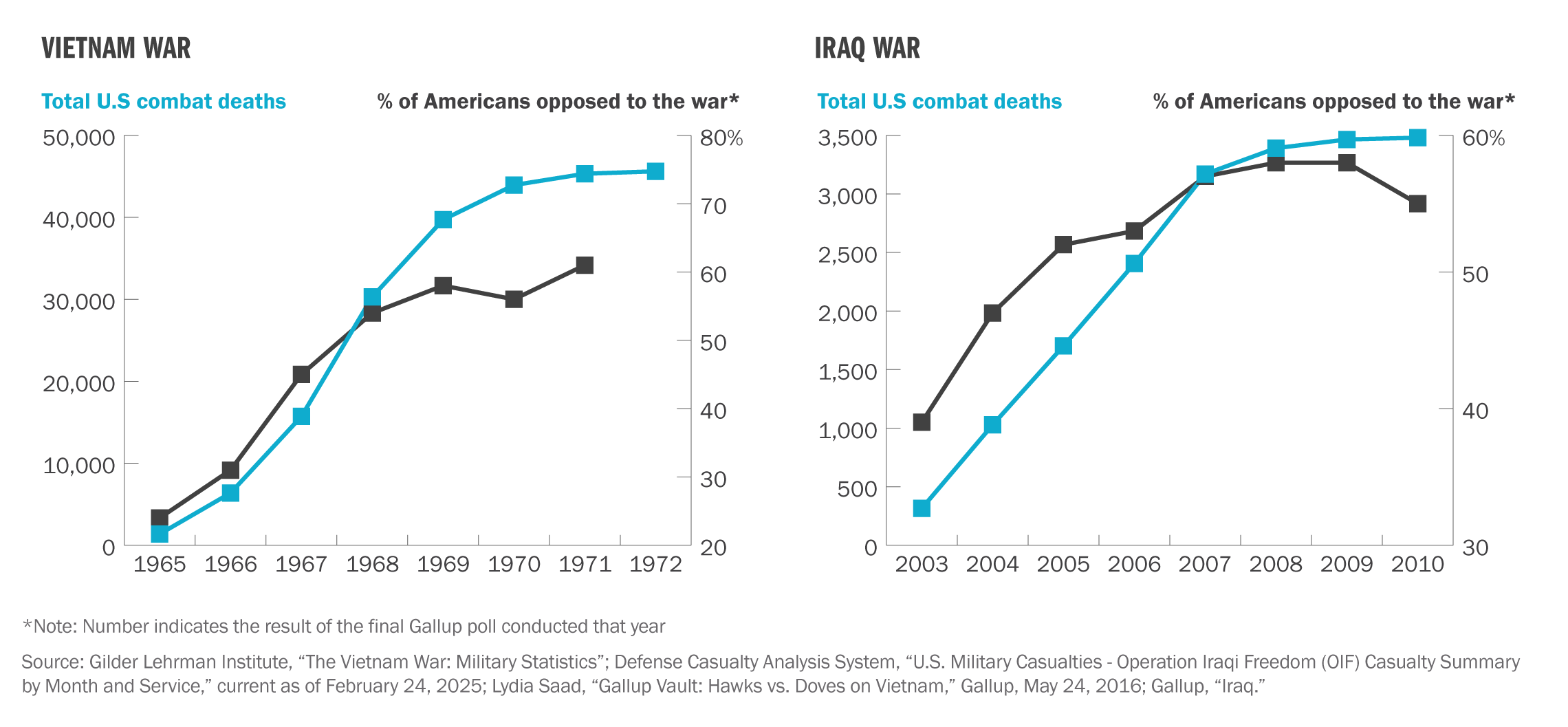

Casualties and public opinion in the Vietnam and Iraq wars

Wars tend to lose public support as casualties increase, especially when the aims of those wars seem undefined, as was the case in Vietnam and Iraq.

War is costly in both blood and treasure, and resources are ultimately limited, no matter how powerful in relative terms a state may be. Societies are willing to undertake monumental sacrifices if their national survival is at stake, but are apt to become skeptical for both self-interested and moral reasons if their blood and treasure is expended arbitrarily. Ultimately, if too many costs and too few benefits are presented to the public, wars will become unpopular and it will be harder for policymakers to sustain them without being punished.12Mark A. Lorell, Charles T. Kelley, Jr., and Deborah R. Hensler, Casualties, Public Opinion, and Presidential Policy During the Vietnam War (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 1985). This could be seen prominently in the wars in Korea and Vietnam. In both cases, the United States faced foes that were weaker but nonetheless more resolute—resulting in a grim stalemate in Korea, where a tense armistice has held ever since, and a traumatic defeat in Vietnam.

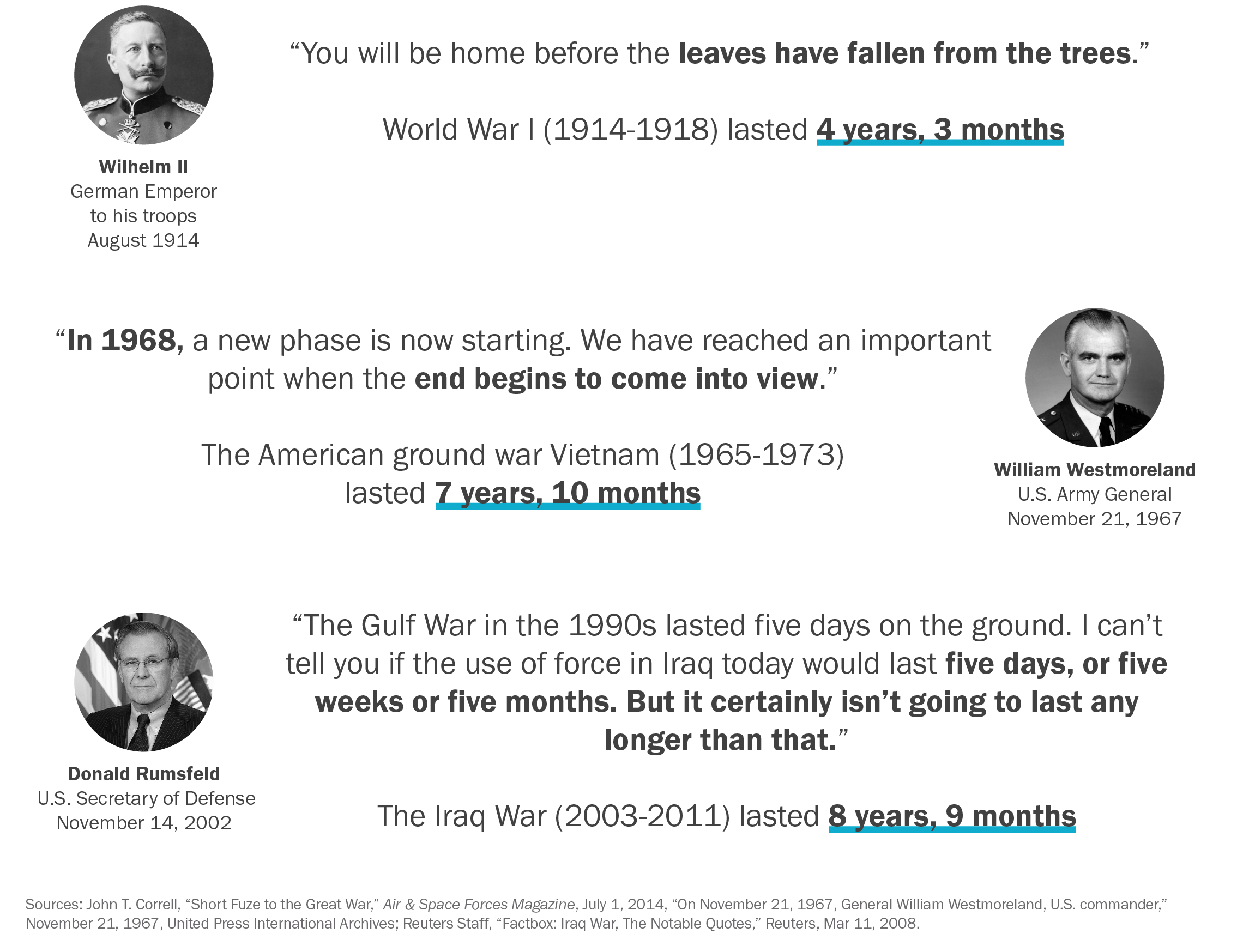

Costs of war also have a tendency to gradually increase beyond anticipation, and new objectives often proliferate the longer a war continues.13John J. Mearsheimer, Conventional Deterrence (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1983), 23. Initial designs to fight quick, light, cheap wars often succumb to “mission creep” and slowly bleed the initiator. Ironically, attempting to pull off an invasion on the cheap as quickly and with as few troops as possible can end up costing more in blood and treasure in the long run. The wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, for example, cost significantly more in real dollars than the wars in Vietnam and Korea, despite rosy initial assessments.14Anthony H. Cordesman, “U.S. Military Spending: The Cost of Wars,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, July 10, 2017, https://www.csis.org/analysis/us-military-spending-cost-wars. This despite the fact that North Korea and North Vietnam had military and financial support from major powers that the insurgencies in Afghanistan and Iraq didn’t, suggesting that war is becoming more expensive in general.15Posen, Restraint, 25.

Many are tempted to believe that war is the most effective way to get what one wants, but war is often poorly suited to achieve constructive political objectives abroad, particularly when there is a lack of will. The nineteenth-century Prussian military theorist Carl von Clausewitz famously said, “war is the continuation of policy by other means.”16Carl von Clausewitz, On War, Michael Howard and Peter Paret, eds. and trans. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1984), 87. War may be the ultima ratio in international politics, but it is only purposeful if it serves to establish a better peace post bellum; otherwise war is simply the unleashing of senseless violence at great cost and risk.17Clausewitz, On War, 76–77; Clausewitz, On War, 86–87.

Militaries destroy—people, weapons, buildings, equipment, infrastructure, etc.—and this may be appropriate in order to stop a vital threat. But it can hardly serve any worthwhile political purpose if the result is simply to reduce a society to ash and rubble. If the political objective is to create a new society far afield—a goal which is likely only achievable under extremely particular conditions—it will require enormous resources and the consent of the population to endow new leaders and institutions with legitimacy and governing capacity. Bullets and bombs are ill-suited to this purpose.

Total costs to the U.S. of major wars

Given the heavy costs of war and the potential consequences of defeat, it is wise for states to undertake war only when necessary, even if a powerful state is facing down a weaker counterpart. Indeed, because military power is derived from other resources, vast differentials in power likely also indicate an abundance of other diplomatic and economic means at the disposal of the stronger state to achieve an acceptable deal. Nonetheless, powerful states are frequently tempted to compel weaker states to bend to their will through force, rather than accept unsatisfying compromises or shake hands with unsavory leaders.

Hubris and nemesis

The experience of the Vietnam War led to a revision of U.S. strategic thinking during the late Cold War, particularly among military officials who had experienced the calamity firsthand. During the Reagan administration, then-chairman of the Joint Chiefs Colin Powell, a Vietnam veteran, along with then-secretary of defense Casper Weinberger, defined a set of principles regarding conditions for using military force, now known as the “Powell-Weinberger Doctrine.” Among these were stipulations that U.S. vital interests be at stake, that the political objectives of the war be defined in advance, and that the United States be prepared to use overwhelming force to win, seeking to avoid mission creep or getting bogged down in an endless quagmire.18Casper Weinberger, “The Uses of Military Power,” remarks prepared for delivery to the Washington Press Club, November 28, 1984, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/military/force/weinberger.html; Walter LaFeber, “The Rise and Fall of Colin Powell and the Powell Doctrine,” Political Science Quarterly 124, no. 1 (Spring, 2009): 71–93. For disagreements within the Reagan and Bush administrations over the use of force, see Mann, Rise of the Vulcans, 179–197.

A turning point came on the eve of the Soviet Union’s collapse with the First Gulf War. At first blush, the Gulf War seemed to affirm the prudence of the Powell-Weinberger Doctrine. While some, including Powell himself, questioned whether the interests involved were vital enough to warrant the use of force, it was determined by the George H.W. Bush administration that Iraq’s military buildup as a result of the Iran-Iraq War made it a potential contender for regional hegemony, that its invasion of Kuwait put it in arm’s reach of the strategically significant oil fields of Saudi Arabia, and that it now threatened unacceptable influence over the global oil market on which the industrialized world depended.19Lawrence Freedman and Efraim Karsh, The Gulf Conflict, 1990–1991: Diplomacy and War in the New World Order (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1993), 51, 74, 92. For a compelling argument that the threat from Iraq was exaggerated and could have been contained without resorting to war, see Christopher Layne, “Why the Gulf War Was Not in the National Interest,” Atlantic Monthly (July 1991): 55–81. The United States therefore took it upon itself to mobilize half a million troops with the limited objectives of ejecting Iraqi forces from Kuwait and destroying most of their capability for future aggression, while leaving the much-diminished Ba’athist regime in place to counterbalance Iran.20See, for instance, later remarks by Brent Scowcroft, who was national security advisor during the war: “One of our objectives was not to have Iraq split up into constituent parts, because… it’s a fundamental interest of the United States to keep a balance in that area between Iraq and Iran.” Interview given in the documentary “The War Behind Closed Doors,” PBS Frontline, February 20, 2003, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/frontline/documentary/showsiraq/.

However, the seeming success of the war led many policymakers and analysts to learn false lessons. The overwhelming demonstration of American military superiority helped break so-called “Vietnam syndrome”—a national skepticism toward the use of force abroad that had persisted since the Vietnam War—and along with the fall of the Soviet Union helped produce two illusions that would drive the subsequent wars of the unipolar moment.

First, developments in military technology at the end of the Cold War led many U.S. leaders to believe that they could fight wars by relying largely on airpower, precision-guided weapons, and high-tech ISR (intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance) while deploying fewer, if any, ground troops, thereby minimizing U.S. casualties.21Harvey M. Sapolsky and Jeremy Shapiro, “Casualties, Technology, and America’s Future Wars,” Parameters 26, no. 2 (Summer 1996): 119–127; Michael O’Hanlon, “Can High Technology Bring U.S. Troops Home?” Foreign Policy 113 (Winter 1998–1999): 72–86. This “revolution in military affairs” (RMA) was seemingly demonstrated during the Gulf War, the air campaign the U.S. conducted against Serbia during the Kosovo War, and the initial phase of the Afghanistan War.22On the RMA, see Andrew W. Marshall, “Some Thoughts on Military Revolutions,” Office of Secretary of Defense, August 23, 1993, https://stacks.stanford.edu/file/druid:yx275qm3713/yx275qm3713.pdf; Andrew F. Krepinevich, “Cavalry to Computer: The Pattern of Military Revolutions,” National Interest 37 (Fall 1994): 30–42; Williamson Murray, “Thinking About Revolutions in Military Affairs,” Joint Force Quarterly 16 (Summer 1997): 69–76. On the impact of this war on military thinking, see Anatol Lieven, “Hubris and Nemesis: Kosovo and the Pattern of Western Military Ascendency and Defeat,” in War Over Kosovo: Politics and Strategy in a Global Age, eds. Andrew J. Bacevich and Eliot A. Cohen (New York: Columbia University Press, 2001), 97–123; Robert A. Pape, “The True Worth of Air Power,” Foreign Affairs, March 1, 2004, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/true-worth-air-power. These campaigns led policymakers to believe they could topple regimes abroad without incurring high casualties or getting stuck in lengthy occupations. As Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld said in 2003, “I don’t do quagmires.”23Michael Hirsch, “Donald Rumsfeld, Iraq War Architect, Dead at 88,” Foreign Policy, June 30, 2021, https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/06/30/donald-rumsfeld-iraq-war-architect-dead-at-88/.

Second, U.S. leaders became convinced that having “won” the economic and ideological struggle of the Cold War, they would not be resisted by foreign populations but instead “greeted as liberators.”24“Interview with Vice President Dick Cheney,” Meet the Press, NBC, March 16, 2003, https://www.leadingtowar.com/PDFsources_claims_noweapons2/2003_03_16_NBCmtp.pdf. The United States itself seemed a uniquely providential force for human progress with the winds of history at its back.25See, for example, Joshua Muravchik, Exporting Democracy: Fulfilling America’s Destiny (Washington, D.C.: American Enterprise Institute Press, 1992); Walter A. McDougall, The Tragedy of U.S. Foreign Policy: How America’s Civil Religion Betrayed the National Interest (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2016), 1–31, 339–358. It was not believed merely that the United States had outlasted a great power rival in the Soviet Union, but that American-style liberal capitalism had outcompeted all alternatives as a universal ideological paradigm.26This was the basic thesis developed by Francis Fukuyama, “The End of History?” National Interest, no. 16 (Summer 1989): 3–18; Fukuyama, The End of History and the Last Man (New York: Free Press, 1992). Scenes of popular mobilization in the states behind the Iron Curtain and demonstrations in Tiananmen Square seemed to confirm that Western institutions and values held a ubiquitous appeal for which all the peoples of the world hungered.

Presumably, if only the last ossified dictatorships in the world could be swept away, their former subjects would gratefully embrace the United States and the model it provided.27See, for example, George W. Bush, “President Bush Discusses Freedom in Iraq and Middle East,” speech to the National Endowment for Democracy, U.S. Chamber of Commerce, November 6, 2003, https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/news/releases/2003/11/20031106-2.html. Also see Mann, Rise of the Vulcans, 198–215; Krauthammer, Democratic Realism. As George W. Bush said in his Second Inaugural Address, “it is the policy of the United States to seek and support the growth of democratic movements and institutions in every nation and culture, with the ultimate goal of ending tyranny in our world.”28George W. Bush, “Second Inaugural Address,” American Presidency Project, January 20, 2005, https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/inaugural-address-13. The ideological intoxication of the “unipolar moment” produced a profound misapprehension in the minds of U.S. policymakers and war-planners that the universal appeal of “freedom”—as Americans define it—was stronger than the tendency by local identity groups to resist foreign occupation and domination.

Policymakers therefore overestimated the amount of popular consent they and the client governments they installed would encounter, while underestimating (or underselling) the number of boots on the ground—and therefore casualties—they would need for their expansive aims to be attained. For example, force planners at the Pentagon vastly underestimated the troop levels that would be needed for a post-invasion occupation force in Iraq—largely on the assumption that American troops would be welcomed by the local population.29“Statement of Paul Wolfowitz to the Committee on the Budget,” U.S. House of Representatives, February 27, 2003, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-108hhrg85421/html/CHRG-108hhrg85421.htm. For a detailed account of Iraq war-planning, including then-secretary of defense Donald Rumsfeld’s repeated demands to reduce force size, see Bob Woodward, Plan of Attack (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2004). Yet while airpower can play an important role in destroying an enemy’s forces, victory in warfare often comes down to ground troops taking and holding territory.30Also see Robert A. Pape, “Hammer and Anvil: Coercing Rival States, Defeating Terrorist Groups, and Bombing to Win,” Aether: A Journal of Strategic Airpower & Spacepower 1, no. 1 (Spring 2022): 106–117. U.S. occupation forces rapidly faced resistance, were unable to maintain law and order and contain a spiraling civil war, and were faced with an open-ended nation-building project for which military forces were ill-suited.

Don’t trust quick war predictions

Those inspired to use U.S. military force to serve the end of foreign nation-building saw a precedent in the successful rehabilitations of Germany and Japan following World War II.31“Newsmaker Interview with Paul Wolfowitz,” PBS News, March 28, 2004, https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/newsmaker-interview-with-paul-wolfowitz. Also see Amitai Etzioni, “The Folly of Nation Building,” National Interest 120 (July/August 2012): 60–68. This, however, overlooked the vast differences in circumstances between the post-World War II and post-9/11 cases. First, having largely destroyed Germany and Japan, the United States committed millions of troops to occupying them, invested in rebuilding them through programs like the Marshall Plan, and integrated them into international economic institutions like GATT and the IMF. Accounting for a full half of all world economic output at the end of the war, the United States had both the capability and the interest to go to these monumental lengths to put its former enemies, now allies, back on their feet. Second, Germany and Japan both faced a new external threat from the Soviet Union, against which the United States served as a security guarantor.32Benjamin Denison, “The More Things Change, the More They Stay the Same: The Failure of Regime-Change Operations,” Cato Institute, January 6, 2020, https://www.cato.org/policy-analysis/more-things-change-more-they-stay-same-failure-regime-change-operations. Third, both Germany and Japan already had experience with democratic government and industrialization, providing an indigenous institutional basis for their rapid independent development and self-government.33David M. Edelstein, “Occupational Hazards: Why Military Occupations Succeed or Fail,” International Security 29, no. 1 (Summer, 2004): 49–91; Jonathan Monten, “Intervention and State-Building: Comparative Lessons from Japan, Iraq, and Afghanistan,” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 656, no. 1 (November 2014): 173–191.

These conditions for democratic nation-building did not apply in Afghanistan or Iraq. Having overturned the Taliban and Ba’athist regimes, the United States quickly became an unpopular occupier. Rather than facing powerful state rivals, U.S. troops were instead confronted by popular insurgencies that gained legitimacy through their resistance. The new governments lacked legitimacy in the eyes of the population or independent institutions to govern, leaving U.S. occupation forces holding the bag.34David A. Lake, The Statebuilder’s Dilemma: On the Limits of Foreign Intervention (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2016). As a result, both Afghanistan and Iraq became prolonged occupations, requiring additional surges of ground troops to restore a minimum of stability, without being able to resolve the underlying political problems.

Particularly in Iraq, the U.S. provisional authority’s notorious “de-Ba’athification” policy made virtually all members of the Iraqi state and political class unemployable overnight, encouraging many of them to join forces with the emerging Sunni fundamentalist insurgency.35Bob Woodward, State of Denial (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2006). In a dynamic which Barry Posen has called “the ethnic security dilemma,” the inability to preserve law and order produced an incentive to align oneself with one paramilitary group before being targeted by another.36Barry R. Posen, “The Security Dilemma and Ethnic Conflict,” Survival 35, no. 1 (Spring 1993): 27–47. Eventually, a weak government dominated by the Shia majority came to power, increasing Iran’s influence in the region while alienating large portions of the Sunni population that turned to al-Qaeda and later ISIS, spreading regional chaos beyond Iraq.

In subsequent interventions in Libya and Syria, the United States sought to avoid a repeat of the costly occupations of Afghanistan and Iraq, while still attempting to overthrow regimes Washington disliked. These “hit-and-run” regime change efforts did not result in happy outcomes either. In Libya, NATO airstrikes helped rebel forces on the ground overthrow Gaddafi, but as in Iraq, in the absence of the old regime, the country splintered into rival militias and open-ended civil war.37Micah Zenko, “The Big Lie About the Libyan War,” Foreign Policy, March 22, 2016, https://foreignpolicy.com/2016/03/22/libya-and-the-myth-of-humanitarian-intervention/.

In Syria, the U.S. covertly supported rebel forces against the Assad regime, but with the outbreak of civil war and the stunning emergence of ISIS, soon found itself working at cross-purposes between its goals of overthrowing Assad and combating transnational terrorism.38Mark Mazzetti, Adam Goldman, and Michael S. Schmidt, “Behind the Sudden Death of a $1 Billion Secret C.I.A. War in Syria,” New York Times, August 2, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/02/world/middleeast/cia-syria-rebel-arm-train-trump.html; Charles Glass, “Tell Me How this Ends,” Harper’s Magazine (February 2019): 51–61. After more than a decade of civil war, the hollowed-out Assad regime fell in 2024 to an al-Qaeda offshoot—an odd “victory” for U.S. policy in the wake of the “Global War on Terror” that prolonged U.S. entanglement in the region. The United States, particularly during the Obama administration, also expanded its drone assassination program, viewing drones as a way to keep killing enemies without incurring casualties. While these more limited interventions and targeted killings helped sow chaos and resentment, they did not obviously advance worthwhile U.S. interests, and arguably damaged them.39Benjamin H. Friedman, “Rethinking Drone Warfare,” in Our Foreign Policy Choices: Rethinking America’s Global Role, ed. Christopher Preble et al. (Washington D.C: Cato Institute, 2016), https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep24890.17.

While weaker regimes can be overthrown fairly easily, the aftermath tends to be a debacle. The wars in Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, and Syria have all failed to produce sustainable liberal democracies and have made humanitarian conditions worse. They have been counterproductive to stated U.S. interests, allowing Iran to increase its regional influence and for terrorist groups like ISIS to fester. They have also encouraged regimes that do not wish to be overthrown, such as Iran and North Korea, to pursue their own nuclear capabilities to avoid the same fate as Saddam and Gaddafi.

Putting diplomacy back at the center of U.S. statecraft

According to realist theory, the end of unipolarity, which arrived when China and (arguably) Russia entered into the ranks of the great powers, should compel U.S. policymakers to be more cautious and selective in their use of military force. How gracefully the United States adapts to its changing security environment—and how unscathed it emerges from its post-Cold War misadventures—depends in large part on its ability to lean more heavily in the future on diplomacy and compromise than compellence and coercion.

In judging the conditions under which the use of force might be justified, the Powell-Weinberger doctrine continues to provide good rules of thumb. However, given the United States’ persistently favorable power position, the potential threats to its core security interests—sovereignty, territory, population, and the balance of power—could only emanate from other nuclear-armed great powers. The task of defending vital U.S. security interests therefore falls primarily under the rubric of deterrence—the subject of the next paper in this series—not the use of force as it was understood in the pre-nuclear age. Defending some 335 million Americans, a continental-sized landmass, maritime passage on the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, and if necessary the political division of the industrialized Eurasian rimland are not small tasks, but they are appropriate to the means and circumstances of the United States.40Indeed, it is an open question whether even preventing the emergence of a Eurasian hegemon is as salient an objective in a world of nuclear weapons. See, for example, Robert W. Tucker, A New Isolationism: Threat or Promise? (New York: Universe Books, 1972), 39–54; Jervis, Meaning of the Nuclear Revolution, 228–232; Stephen Van Evera, “A Farewell to Geopolitics,” in To Lead the World: American Strategy After the Bush Doctrine, ed. Melvyn P. Leffler and Jeffrey W. Legro (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 14.

There are few if any interests significant enough to warrant major U.S. military interventions in distant small states—which by definition have scant effects on the global balance of power and certainly don’t pose an existential threat to the U.S. homeland. Tasks like counterterrorism are better conducted through cooperative intelligence and police work than by military invasions and foreign nation-building. This also means there are few international political circumstances where the United States cannot afford to negotiate and cut mutually acceptable deals. On the contrary, by virtue of its distance from the geopolitical hotbed of Eurasia and its diverse sources of power and influence, the United States stands to disproportionately gain from negotiating with others and forging a durable modus vivendi.

Unfortunately, recent decades have been characterized by a tendency to engage in diplomacy only with friends and allies, while engaging with adversaries only through military threats or economic sanctions. Domestic American discourse often mischaracterizes meaningful diplomacy with competitors or adversaries as “appeasement.” U.S. policymakers fear being perceived as weak or credulous, making it politically safer to act belligerently. This dynamic only serves to make disputes more intractable, preventable crises more common, and the risk of escalation into open conflict more likely. By eschewing diplomacy, the United States sacrifices its advantages and forgoes meaningful opportunities.

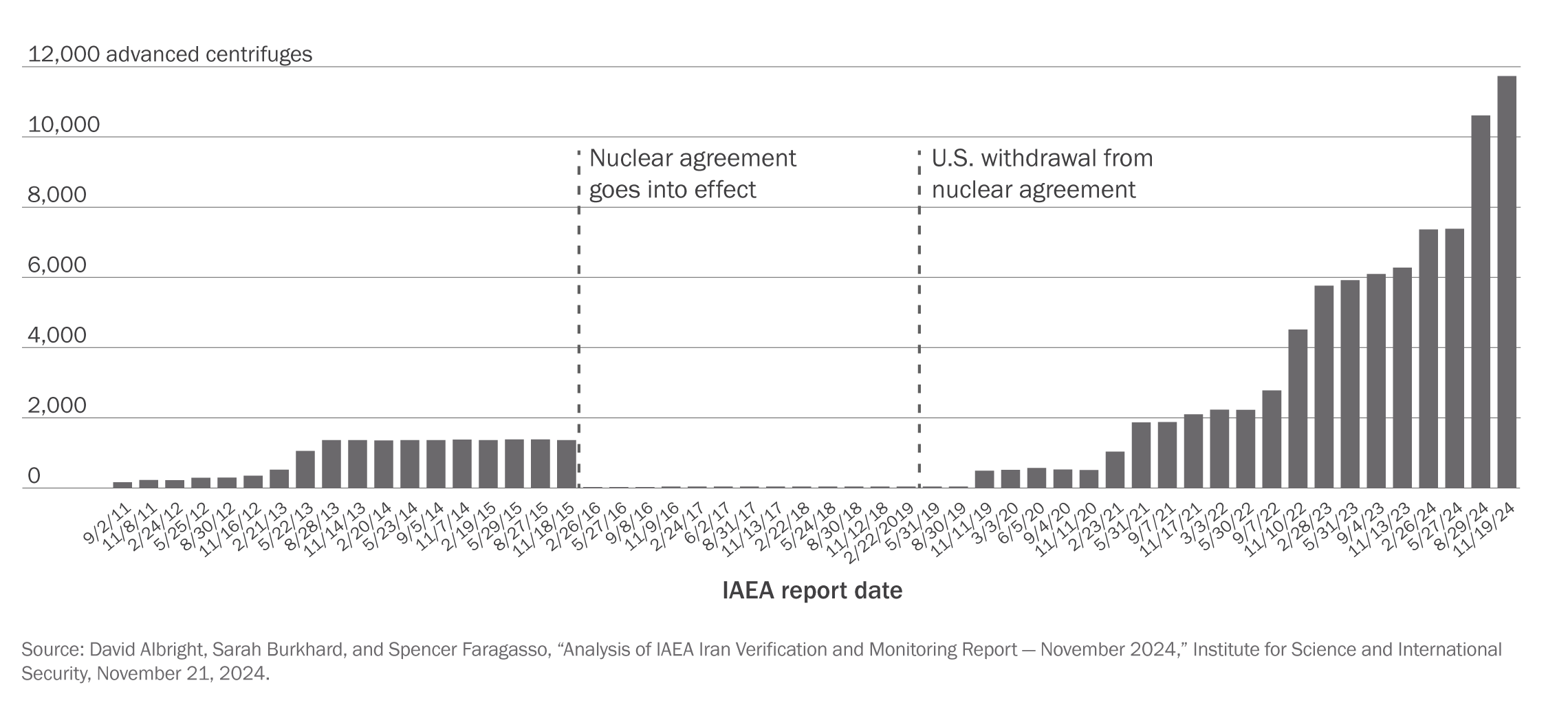

When U.S. policymakers attempt to resolve disputes by cutting deals, the benefits are demonstrable. When the United States was on the brink of attacking Syria in 2013 due to allegations of chemical weapons use, the Obama administration, reluctant to get ensnared in a new quagmire, instead cooperated with Russia to get Damascus to turn over its biological and chemical weapons to the UN.41Michael R. Gordon, “U.S. and Russia Reach Deal to Destroy Syria’s Chemical Arms,” New York Times, September 14, 2013, https://www.nytimes.com/2013/09/15/world/middleeast/syria-talks.html. The JCPOA agreement with Iran, the signal diplomatic achievement of the Obama administration, successfully stalled Iran’s drive to acquire nuclear weapons, opening up a path to stabilize relations with Tehran and the region in general. By contrast, abandoning the JCPOA and pursuing a “maximum pressure campaign” against Iran has put Washington back on a collision course with Tehran over its nuclear program.

Iranian nuclear centrifuges over time

Contrary to charges that the JCPOA deal with Iran amounted to a surrender, it dramatically reduced Iran’s nuclear centrifuges.

Ironically, the impulse for Iran and North Korea to acquire a nuclear deterrent is reinforced by the example set by states which, having abandoned their own deterrent capabilities, were overthrown by the United States. The most salient example is Libya, which ended its WMD program and tried to forge a rapprochement with the West. This did not prevent the United States and its NATO allies from pursuing regime change in Libya less than a decade later, leading to the demise of Gaddafi. The signal to Tehran and Pyongyang is that the United States cannot be trusted, and they would be wise to prepare for the worst.42See, for example, Megan Specia and David E. Sanger, “How the ‘Libya Model’ Became a Sticking Point in North Korea Nuclear Talks,” New York Times, May 16, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/16/world/asia/north-korea-libya-model.html.

Conclusion

It is understandable that humanitarian concerns and the desire to spread democracy produce an impulse among policymakers and the public to “do something.” Pursuing regime change, however, is not the right solution if U.S. security interests significant enough to warrant a prolonged occupation are not at stake. If the population of a foreign country is unable to overthrow a tyrannical regime and establish a legitimate and stable governing coalition on their own, they will most likely be unable to govern even if the U.S. overthrows the regime for them. The more likely outcome is a descent into a Hobbesian state of nature where wanton violence is supreme.

The United States should instead apply Hippocrates’ principle of “first, do no harm.” While there is plenty of inhumane violence in the world, the United States should not therefore undertake military interventions which are likely to make things worse. Military force is a blunt tool designed to destroy people, machinery, and infrastructure, not a precise surgical instrument or a constructive force in itself.

The United States should also apply a second medical principle to promote democracy: “physician, heal thyself.” As Kenneth Waltz pointed out, states not only interact through competition but through socialization. The international system punishes states which act foolishly and “selects” for states which follow successful strategies. Other states keen to survive, in turn, emulate best practices and successful models.43See, for example, Megan Specia and David E. Sanger, “How the ‘Libya Model’ Became a Sticking Point in North Korea Nuclear Talks,” New York Times, May 16, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/16/world/asia/north-korea-libya-model.html. Waltz, Theory of International Politics, 74–77, 127–128.

The best way for the United States to promote democracy abroad is to show it to be as successful at home as possible, convincing others that it is the most competitive model in order to survive and thrive in an anarchical world. If we believe in democracy, want to sustain the foundations of U.S. power, and wish to improve our own quality of domestic life, this should be our national priority, rather than attempting to find our purpose through wars on the other side of the world.

Endnotes

- 1Robert Jervis, The Meaning of the Nuclear Revolution: Statecraft and the Prospect of Armageddon (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1989).

- 2Kenneth N. Waltz, “The Stability of a Bipolar World,” Daedalus 93, no. 3 (Summer, 1964): 881–909; Kenneth N. Waltz, Theory of International Politics (Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press, 1979), 170–176.

- 3William C. Wohlforth, “The Stability of a Unipolar World,” International Security 24, no. 1 (Summer, 1999): 5–41; Michael Mastanduno, “Preserving the Unipolar Moment: Realist Theories and U.S. Grand Strategy After the Cold War,” International Security 21, no. 4 (Spring, 1997): 49–88.

- 4Kenneth N. Waltz, “Structural Realism After the Cold War,” International Security 25, no. 1 (Summer 2000): 5–41; Robert Jervis, “Unipolarity: A Structural Perspective,” World Politics 61, no. 1 (January 2009): 188–213; Nuno P. Monteiro, “Unrest Assured: Why Unipolarity is Not Peaceful,” International Security 36, no. 3 (Winter 2011/2012): 9–40.

- 5Christopher Layne, “The Unipolar Illusion: Why New Powers Will Rise,” International Security 17, no. 4 (Spring, 1991): 5–51; Kenneth N. Waltz, “The Emerging Structure of International Politics,” International Security 18, no. 2 (Fall 1993): 44–79.

- 6I borrow this criterion from Barry R. Posen, Restraint: A New Foundation for U.S. Grand Strategy (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2014), 1–3.

- 7Sidita Kushi and Monica Duffy Toft, “Introducing the Military Intervention Project: A New Dataset on US Military Interventions, 1776-2019,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 67, no. 4 (April 2023): 752–779; Barbara Salazar Torreon and Sofia Plagakis, “Instances of Use of United States Armed Forces Abroad, 1798–2023,” Congressional Research Service, June 7, 2023, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R42738/41; Jennifer Kavanagh, et al., Characteristics of Successful U.S. Interventions (Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 2019), https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR3062.html.

- 8“Excerpts From Pentagon’s Plan: ‘Prevent the Re-Emergence of a New Rival’,” New York Times, March 8, 1992, https://www.nytimes.com/1992/03/08/world/excerpts-from-pentagon-s-plan-prevent-the-re-emergence-of-a-new-rival.html; James Mann, Rise of the Vulcans: The History of Bush’s War Cabinet (New York: Viking, 2004), 198–215. Also see the influential article by Charles Krauthammer, “The Unipolar Moment,” Foreign Affairs 70, no. 1 (1990/1991): 23–33.

- 9Quoted in Christopher A. Preble, The Power Problem: How American Military Dominance Makes Us Less Safe, Less Prosperous, and Less Free (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2009), 4.

- 10This is the main topic of John J. Mearsheimer, The Great Delusion: Liberal Dreams and International Realities (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2018). For examples of “militant liberalism,” see Bill Clinton, “Address to a Joint Session of Congress on the State of the Union,” U.S. Government Publishing Office, January 25, 1994, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/WCPD-1994-01-31/pdf/WCPD-1994-01-31-Pg148.pdf; Bill Clinton, “Address to a Joint Session of Congress on the State of the Union,” American Presidency Project, January 24, 1995, https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/address-before-joint-session-the-congress-the-state-the-union-11; George W. Bush, “Address to a Joint Session of Congress on the State of the Union,” White House, January 9, 2002, https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/news/releases/2002/01/20020129-11.html; William Kristol and Robert Kagan, “Toward a Neo-Reaganite Foreign Policy,” Foreign Affairs 75, no. 4 (July-Aug., 1996): 18–34.

- 11This overlaps with the main thesis of Preble, The Power Problem. Also see Stephen M. Walt, “The Intervention Paradox,” Foreign Policy, April 20, 2011, https://foreignpolicy.com/2011/04/20/the-intervention-paradox/.

- 12Mark A. Lorell, Charles T. Kelley, Jr., and Deborah R. Hensler, Casualties, Public Opinion, and Presidential Policy During the Vietnam War (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 1985).

- 13John J. Mearsheimer, Conventional Deterrence (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1983), 23.

- 14Anthony H. Cordesman, “U.S. Military Spending: The Cost of Wars,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, July 10, 2017, https://www.csis.org/analysis/us-military-spending-cost-wars.

- 15Posen, Restraint, 25.

- 16Carl von Clausewitz, On War, Michael Howard and Peter Paret, eds. and trans. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1984), 87.

- 17Clausewitz, On War, 76–77; Clausewitz, On War, 86–87.

- 18Casper Weinberger, “The Uses of Military Power,” remarks prepared for delivery to the Washington Press Club, November 28, 1984, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/military/force/weinberger.html; Walter LaFeber, “The Rise and Fall of Colin Powell and the Powell Doctrine,” Political Science Quarterly 124, no. 1 (Spring, 2009): 71–93. For disagreements within the Reagan and Bush administrations over the use of force, see Mann, Rise of the Vulcans, 179–197.

- 19Lawrence Freedman and Efraim Karsh, The Gulf Conflict, 1990–1991: Diplomacy and War in the New World Order (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1993), 51, 74, 92. For a compelling argument that the threat from Iraq was exaggerated and could have been contained without resorting to war, see Christopher Layne, “Why the Gulf War Was Not in the National Interest,” Atlantic Monthly (July 1991): 55–81.

- 20See, for instance, later remarks by Brent Scowcroft, who was national security advisor during the war: “One of our objectives was not to have Iraq split up into constituent parts, because… it’s a fundamental interest of the United States to keep a balance in that area between Iraq and Iran.” Interview given in the documentary “The War Behind Closed Doors,” PBS Frontline, February 20, 2003, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/frontline/documentary/showsiraq/.

- 21Harvey M. Sapolsky and Jeremy Shapiro, “Casualties, Technology, and America’s Future Wars,” Parameters 26, no. 2 (Summer 1996): 119–127; Michael O’Hanlon, “Can High Technology Bring U.S. Troops Home?” Foreign Policy 113 (Winter 1998–1999): 72–86.

- 22On the RMA, see Andrew W. Marshall, “Some Thoughts on Military Revolutions,” Office of Secretary of Defense, August 23, 1993, https://stacks.stanford.edu/file/druid:yx275qm3713/yx275qm3713.pdf; Andrew F. Krepinevich, “Cavalry to Computer: The Pattern of Military Revolutions,” National Interest 37 (Fall 1994): 30–42; Williamson Murray, “Thinking About Revolutions in Military Affairs,” Joint Force Quarterly 16 (Summer 1997): 69–76. On the impact of this war on military thinking, see Anatol Lieven, “Hubris and Nemesis: Kosovo and the Pattern of Western Military Ascendency and Defeat,” in War Over Kosovo: Politics and Strategy in a Global Age, eds. Andrew J. Bacevich and Eliot A. Cohen (New York: Columbia University Press, 2001), 97–123; Robert A. Pape, “The True Worth of Air Power,” Foreign Affairs, March 1, 2004, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/true-worth-air-power.

- 23Michael Hirsch, “Donald Rumsfeld, Iraq War Architect, Dead at 88,” Foreign Policy, June 30, 2021, https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/06/30/donald-rumsfeld-iraq-war-architect-dead-at-88/.

- 24“Interview with Vice President Dick Cheney,” Meet the Press, NBC, March 16, 2003, https://www.leadingtowar.com/PDFsources_claims_noweapons2/2003_03_16_NBCmtp.pdf.

- 25See, for example, Joshua Muravchik, Exporting Democracy: Fulfilling America’s Destiny (Washington, D.C.: American Enterprise Institute Press, 1992); Walter A. McDougall, The Tragedy of U.S. Foreign Policy: How America’s Civil Religion Betrayed the National Interest (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2016), 1–31, 339–358.

- 26This was the basic thesis developed by Francis Fukuyama, “The End of History?” National Interest, no. 16 (Summer 1989): 3–18; Fukuyama, The End of History and the Last Man (New York: Free Press, 1992).

- 27See, for example, George W. Bush, “President Bush Discusses Freedom in Iraq and Middle East,” speech to the National Endowment for Democracy, U.S. Chamber of Commerce, November 6, 2003, https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/news/releases/2003/11/20031106-2.html. Also see Mann, Rise of the Vulcans, 198–215; Krauthammer, Democratic Realism.

- 28George W. Bush, “Second Inaugural Address,” American Presidency Project, January 20, 2005, https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/inaugural-address-13.

- 29“Statement of Paul Wolfowitz to the Committee on the Budget,” U.S. House of Representatives, February 27, 2003, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-108hhrg85421/html/CHRG-108hhrg85421.htm. For a detailed account of Iraq war-planning, including then-secretary of defense Donald Rumsfeld’s repeated demands to reduce force size, see Bob Woodward, Plan of Attack (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2004).

- 30Also see Robert A. Pape, “Hammer and Anvil: Coercing Rival States, Defeating Terrorist Groups, and Bombing to Win,” Aether: A Journal of Strategic Airpower & Spacepower 1, no. 1 (Spring 2022): 106–117.

- 31“Newsmaker Interview with Paul Wolfowitz,” PBS News, March 28, 2004, https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/newsmaker-interview-with-paul-wolfowitz. Also see Amitai Etzioni, “The Folly of Nation Building,” National Interest 120 (July/August 2012): 60–68.

- 32Benjamin Denison, “The More Things Change, the More They Stay the Same: The Failure of Regime-Change Operations,” Cato Institute, January 6, 2020, https://www.cato.org/policy-analysis/more-things-change-more-they-stay-same-failure-regime-change-operations.

- 33David M. Edelstein, “Occupational Hazards: Why Military Occupations Succeed or Fail,” International Security 29, no. 1 (Summer, 2004): 49–91; Jonathan Monten, “Intervention and State-Building: Comparative Lessons from Japan, Iraq, and Afghanistan,” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 656, no. 1 (November 2014): 173–191.

- 34David A. Lake, The Statebuilder’s Dilemma: On the Limits of Foreign Intervention (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2016).

- 35Bob Woodward, State of Denial (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2006).

- 36Barry R. Posen, “The Security Dilemma and Ethnic Conflict,” Survival 35, no. 1 (Spring 1993): 27–47.

- 37Micah Zenko, “The Big Lie About the Libyan War,” Foreign Policy, March 22, 2016, https://foreignpolicy.com/2016/03/22/libya-and-the-myth-of-humanitarian-intervention/.

- 38Mark Mazzetti, Adam Goldman, and Michael S. Schmidt, “Behind the Sudden Death of a $1 Billion Secret C.I.A. War in Syria,” New York Times, August 2, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/02/world/middleeast/cia-syria-rebel-arm-train-trump.html; Charles Glass, “Tell Me How this Ends,” Harper’s Magazine (February 2019): 51–61.

- 39Benjamin H. Friedman, “Rethinking Drone Warfare,” in Our Foreign Policy Choices: Rethinking America’s Global Role, ed. Christopher Preble et al. (Washington D.C: Cato Institute, 2016), https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep24890.17.

- 40Indeed, it is an open question whether even preventing the emergence of a Eurasian hegemon is as salient an objective in a world of nuclear weapons. See, for example, Robert W. Tucker, A New Isolationism: Threat or Promise? (New York: Universe Books, 1972), 39–54; Jervis, Meaning of the Nuclear Revolution, 228–232; Stephen Van Evera, “A Farewell to Geopolitics,” in To Lead the World: American Strategy After the Bush Doctrine, ed. Melvyn P. Leffler and Jeffrey W. Legro (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 14.

- 41Michael R. Gordon, “U.S. and Russia Reach Deal to Destroy Syria’s Chemical Arms,” New York Times, September 14, 2013, https://www.nytimes.com/2013/09/15/world/middleeast/syria-talks.html.

- 42See, for example, Megan Specia and David E. Sanger, “How the ‘Libya Model’ Became a Sticking Point in North Korea Nuclear Talks,” New York Times, May 16, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/16/world/asia/north-korea-libya-model.html.

- 43See, for example, Megan Specia and David E. Sanger, “How the ‘Libya Model’ Became a Sticking Point in North Korea Nuclear Talks,” New York Times, May 16, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/16/world/asia/north-korea-libya-model.html. Waltz, Theory of International Politics, 74–77, 127–128.