Avoid policies that drive Russia and China toward an anti-U.S. coalition

- In the 1970s, the U.S. capitalized on the Sino-Soviet split by improving relations with China, the weaker power, making the chances of a Moscow-Beijing communist monolith against the U.S. and its allies less likely.

- Much has changed since the Cold War, yet it remains in the U.S. interest to avoid Russia and China—the only two near-peer, nuclear-armed U.S. competitors—combining their economic and military power.

- A de facto or de jure alliance between Russia and China that significantly pooled military power and foreign policy objectives would alter the Eurasian balance of power and disadvantage the U.S.

- The current U.S. approach of dual containment (simultaneously challenging Russia and China) via bases and alliances encourages their cooperation. Mounting a global campaign to pit democracies against autocracies adds to that pressure.

- The threat posed by Russia and China to the U.S. is less if they do not collectively focus military attention and resources against the U.S. and its allies and partners.

- Given political realities and the balance of power, there is more room to temper policy toward Russia to maintain Moscow’s historical wariness of Beijing.

Russia and China’s combined economic and military power compared to the U.S.

An alliance between Russia and China could pool not only their military capabilities, but also their economic prosperity, which is latent military power.

Russia-China relations are in a period of entente

- Mutual suspicion dominated Russia-China relations during much of the Cold War. Yet even as that dynamic persists, the two countries have recently developed a more accommodative, mutually beneficial relationship.

- Russia increasingly relies on China economically. China, in turn, looks to Russia for help challenging U.S. power, modernizing its military, and maintaining stable access to energy imports.

- Russian weapons account for nearly 80 percent of China’s arms imports over the last five years. Chinese purchases have included advanced technology and weapons systems, such as Mi-171 helicopters, Su-35 fighter jets, and the S-400 missile defense system.

- Russian and Chinese militaries have engaged in ambitious exercises over the last decade, with an emphasis on boosting interoperability between their forces on land and at sea. Joint work continues on anti-missile defense, cyber, and space programs.

- China is Russia’s largest trading partner, with totals exceeding $100 billion per year, accounting for 18.3 percent of Russian trade in 2020 (up from 10.5 percent in 2013). Russia has been the largest source for China’s oil imports, or a close second, over the last five years.

- Trade shifts have been exacerbated by U.S. and E.U. sanctions against the Russian economy. Although trade is not necessarily indicative of a shared strategic outlook, it creates common interests.

- Russia and China often vote the same way at the U.N., reflecting aligned interests. Their delegations coordinate at the U.N. Security Council, where they wield their veto power to block or dilute U.S.-sponsored resolutions.

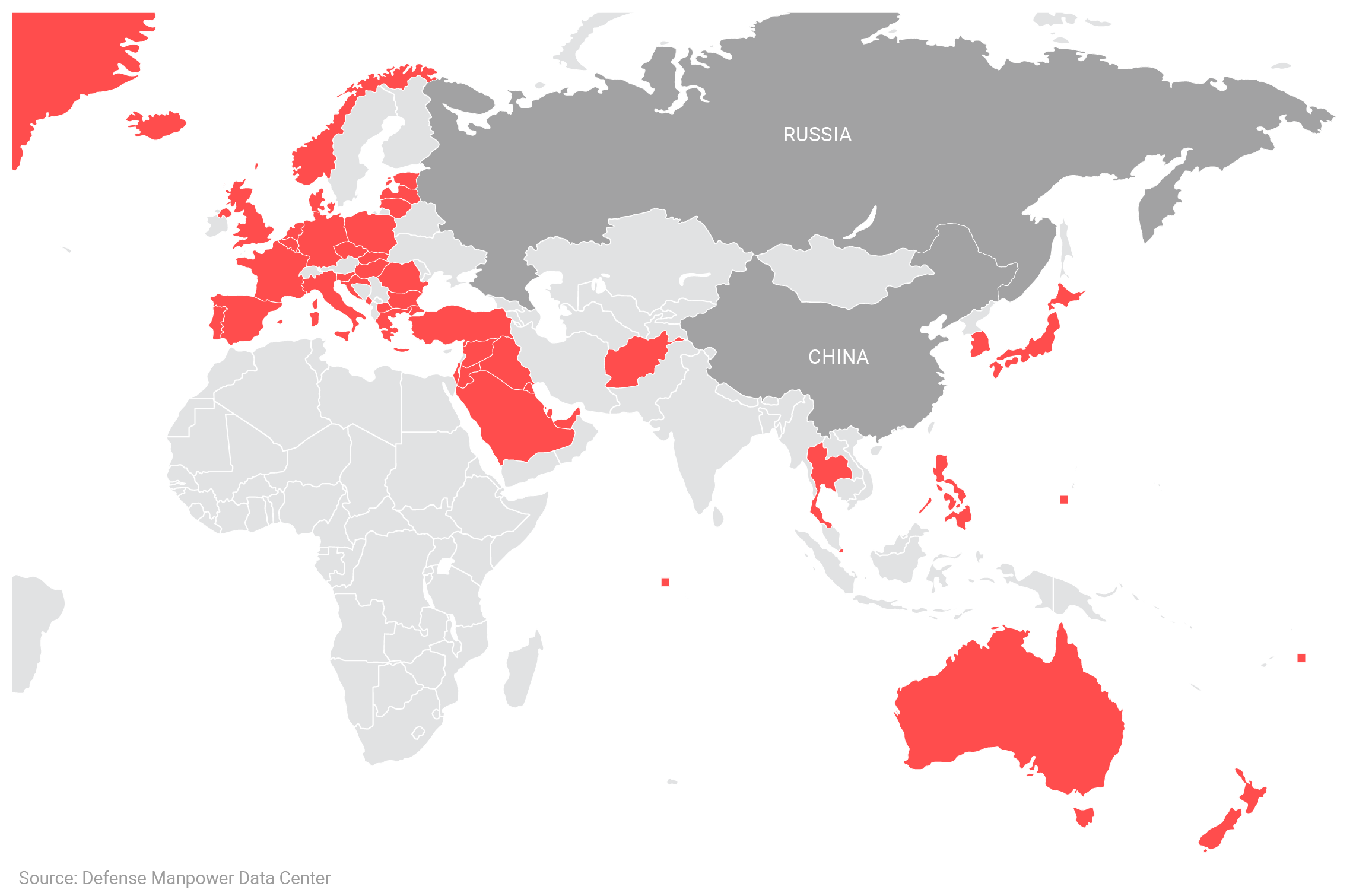

Eurasian U.S. allies and countries with more than 100 U.S. military personnel

Tens of thousands of U.S. troops are deployed to allies and partners near Russia and China, and this encirclement, from their perspective, cannot be interpreted as benign. This helps explain their increased military cooperation

Risks of a Russia-China alliance: Consequence times probability

- Neither Russia nor China now appears eager to establish a formal alliance. Sharing a border and a fraught history, they are more natural antagonists than allies.

- U.S. policy should nonetheless hedge against the risk of a hostile, great power alliance. Combining Russian and Chinese military power could increase the threat to U.S. allies on two fronts, plug both powers’ weaknesses, and drive U.S. military spending increases.

- Together, Russia and China would boast a combined economy of $28.2 T, surpassing the U.S. ($20.9 T); a large manufacturing base; a formidable military-industrial base; and prevalent natural resources (comprising 16 percent of the world’s oil production).

Washington’s foreign policies contributed to recent Sino-Russo cooperation

- U.S.-Russia and U.S.-China relations are tense due to punitive measures, like sanctions, trade restrictions, encirclement of each with military bases, and, with respect to Russia, NATO enlargement.

- U.S. policies, like those outlined in the NSS and NDS—which treat both Russia and China as the leaders of an emerging authoritarian bloc best managed by a U.S. policy of dual containment—add pressures for them to balance against the U.S.

- U.S. secondary sanctions lock Russian entities out of some Western markets and increase Russian dependence on China for export revenue and investment.

- NATO looking to Asia to make itself more relevant would exacerbate this cooperative dynamic. It would (1) distract from NATO’s core mission of defending Europe and (2) raise tensions with China without any obvious benefits.

Do not push Russia and China together—and do not push Russia toward China

- It is unrealistic to enlist Russia in a U.S.-led bloc against China, particularly with U.S.-Russia relations at a post-Cold War low.

- But just as the U.S. reduced the Soviet Union’s threat by opening to China (the junior partner in a potential communist bloc), stabilizing relations with Russia would ease tensions and limit incentives for it to cooperate with Beijing against the U.S.

- The U.S. should review existing sanctions on Russia, reserving them for limited, achievable ends, rather than to signal disapproval of Moscow’s various infractions. The U.S. should not apologize for its values, nor should it subvert its interests to virtue signal.

- U.S. leaders should eschew ideological framing that pits democracies against autocracies, which undermines meaningful diplomatic engagement and reinforces false notions that the U.S. and Russia are implacable foes. Narrow cooperation is in both nations’ interests.

- The U.S. should end NATO enlargement—removing all notions Ukraine or Georgia¬ might join the military alliance—and encourage Europe to take security responsibility for its eastern flank. A U.S. forward troop presence near Russia’s borders poisons relations.