February 18, 2025

Safeguarding U.S. interests in a Ukraine war settlement

Key points

- The United States should pursue a peace deal in Ukraine that serves America’s best interests, even when these diverge from its European partners. The primary U.S. objective should be to achieve a “lasting peace” that endures over the long term.

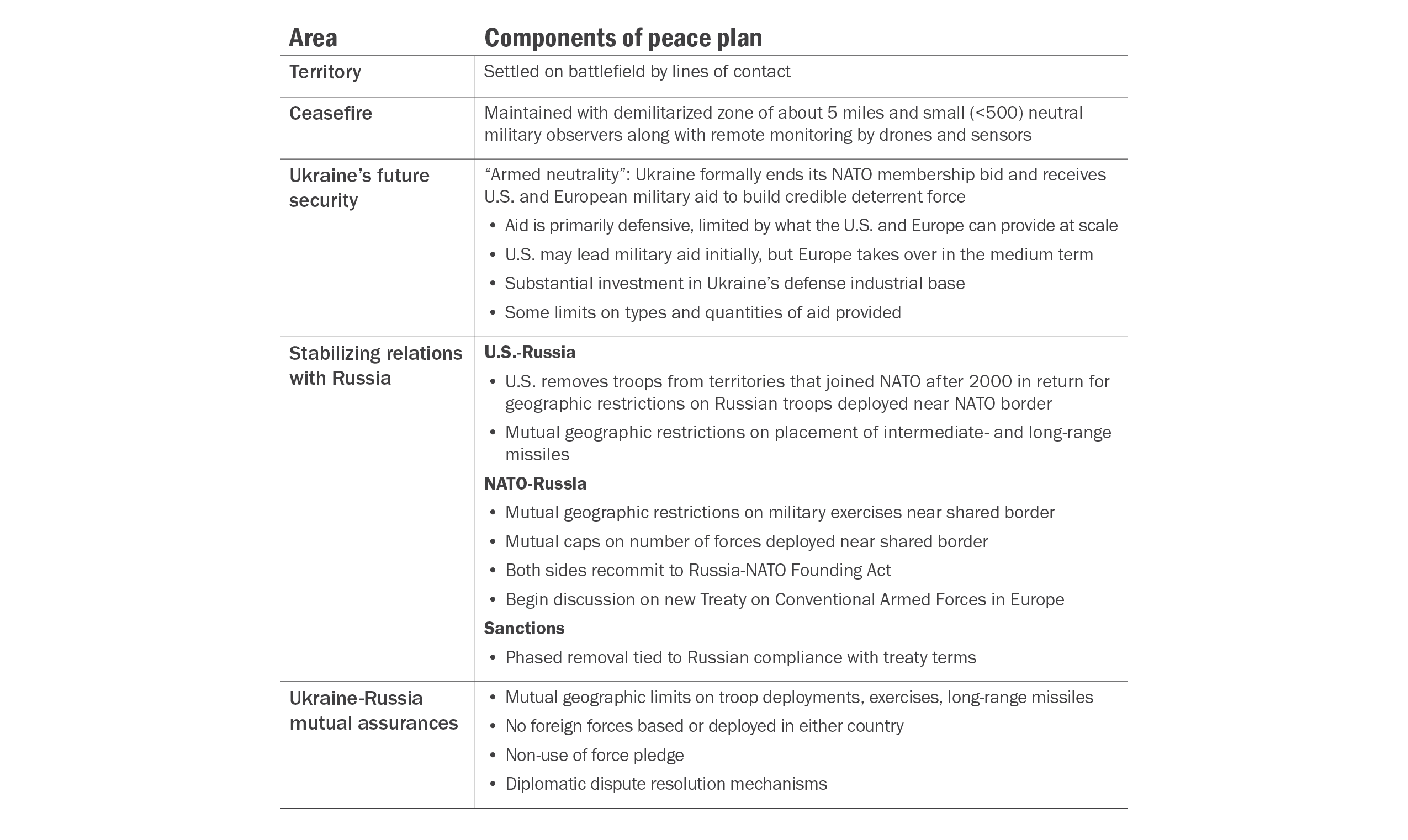

- A final settlement of the Ukraine war should address five key issues: territory; ceasefire terms; arrangements for Ukraine’s future security; stabilizing relationships between Russia and NATO and Russia and the United States; and mutual assurances between Russia and Ukraine. Full resolution of all five dimensions would not be required to end a “hot war,” however.

- Issues of territory will be determined on the battlefield, and any ceasefire should be maintained with a demilitarized zone and some combination of a neutral, international monitoring force and remote and autonomous technologies, lke drones and sensors.

- Offering Ukraine a binding security commitment is not in U.S. interests, whether through NATO or otherwise. Instead, the best option is “armed neutrality,” which would leave Ukraine without external guarantees but help it build a credible, self-sufficient deterrent—with Europe leading the provision of military aid. Mutual security assurances between Ukraine and Russia, including restrictions on locations of forces and weapons, can reduce the risk of renewed conflict.

- The Trump administration should use willingness to talk about the future U.S. role in Europe’s security as a bargaining chip to get Russia to make necessary concessions. The United States gives up little by discussing these issues of high political value to Russia. Some changes in U.S. posture in Europe may also advance U.S. efforts to shift defense burdens to allies and partners.

First steps toward peace

President Donald Trump has made ending the conflict in Ukraine a priority. “I hope it’s fast. Every day people are dying. This war is so bad in Ukraine. I want to end this damn thing,” he reiterated three weeks after taking office.1Edward Helmore, “Trump Says He Has Spoken with Putin about Ending Ukraine War,” Guardian, February 9, 2025, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2025/feb/09/trump-putin-ukraine-war. Trump has said he has a plan to settle the war but has not elaborated on what it entails. Ukraine and Russia, on the other hand, have already put forward their peace proposals, each seeking to protect its own interests. Ukraine’s plan includes NATO membership, long-term military aid, economic support for reconstruction, and accountability for Russia’s aggression.2“What is Zelenskyy’s 10-Point Peace Plan?” Official Website of Ukraine, September 17, 2024, https://war.ukraine.ua/faq/zelenskyys-10-point-peace-plan/; Max Boot, “Zelenskyy’s ‘Victory Plan’ for Ukraine Makes Sense. It Has Little Chance of Being Implemented,” Council on Foreign Relations, October 21, 2024, https://www.cfr.org/expert-brief/zelenskyys-victory-plan-ukraine-makes-sense-it-has-little-chance-being-implemented. Russia’s plan asks for substantial Ukrainian territorial concessions and a neutral and demilitarized Ukraine.3Ruxandra Iordache, “Russia’s Putin Sets Out Conditions for Peace Talks with Ukraine, CNBC, June 14, 2024, https://www.cnbc.com/2024/06/14/russias-putin-outlines-conditions-for-peace-talks-with-ukraine.html.

President Joe Biden never offered a U.S.-backed roadmap to peace during his time in office, deferring instead to Ukraine’s preferences. Asserting that he would support Ukraine “as long as it takes,” Biden was unwilling to admit that U.S. and Ukrainian interests were overlapping but distinct, especially when it came to ending the war. This rhetoric put U.S. interests at risk, seemingly giving Ukraine veto power over U.S. policy.4Joseph R. Biden Jr., “President Biden: What America Will and Will Not Do in Ukraine,” New York Times, May 31, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/05/31/opinion/biden-ukraine-strategy.html.

President Trump’s intention to offer a peace plan of his own is a good first step. After investing $175 billion in Ukraine over the past three years, the United States should be proactive in pushing for a peace agreement that advances U.S. interests at an acceptable cost.5Jonathan Masters and Will Merrow, “How Much U.S. Aid Is Going to Ukraine?” Council on Foreign Relations, September 27, 2024, https://www.cfr.org/article/how-much-us-aid-going-ukraine. The United States, Ukraine, and Europe have some aligned imperatives when it comes to resolving the ongoing war, but also major areas of divergence. By designing and endorsing a peace plan that puts America’s interests first, the Trump administration can safeguard U.S. short- and long-term interests and avoid unwanted obligations.

Summary of proposed peace plan

Defaulting to Ukraine’s proposal or a European one would repeat Biden’s mistake of conflating U.S. and allied positions and put America’s best interests at risk. By advocating for its preferred war settlement, the Trump administration can also advance other priorities, including reducing the U.S. security burden in Europe and shifting NATO responsibilities to its allies.

Trump may not want to reveal his plan too soon but sketching out the details of what a “good” deal for the United States would look like might be essential to getting talks started. It would clarify the bargaining space and jumpstart a diplomatic channel that has been stalled for years. Accordingly, this paper offers the broad outlines of a settlement for the Russo-Ukraine war that puts America first.

Deciding on a U.S.-endorsed peace plan will require Trump and his advisors to clearly define the U.S. interests they want to preserve or advance and the costs and concessions they are willing to take on. American interests at stake in Ukraine are limited. In their policies, though not always their words, U.S. presidents stretching back decades have been clear that Ukraine’s security was not a core U.S. interest worth going to war over. Presidents Obama, Trump, and Biden have all refused to send U.S. military forces to defend the country.6“Clinton Promised Yeltsin Nato Expansion ‘No Threat,’ Newly Declassified Documents Show,” BNE IntelliNews, July 11, 2024, https://www.intellinews.com/clinton-promised-yeltsin-nato-expansion-no-threat-newly-declassified-documents-show-333189/; Jeffrey Goldberg, “The Obama Doctrine,” Atlantic, April 2016, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2016/04/the-obama-doctrine/471525/#3.

However, the United States does have some interest in how the Ukraine war ends. Most importantly, there are benefits to any deal that ends the fighting. Every day that the conflict continues brings the chance of a direct NATO-Russia confrontation or catastrophic escalation through miscalculation. At the same time, any additional Russian territorial gains would further circumscribe Ukraine’s sovereignty and shrink the buffer between Russia and its European neighbors. The same considerations suggest the United States has an interest in achieving a peace that endures. A peace deal that falls apart would once again threaten to entangle the United States in a war with nuclear risk and to bring Russian aggression closer to NATO allies.

What’s more, President Trump should have political motives to want a lasting peace. Resumed war would be a major foreign policy failure and prevent Trump from delivering on one of his main campaign promises. If a collapsed peace deal eventually led to the fall of Kyiv, Trump might be blamed for “losing Ukraine.” A fear of this outcome makes it unlikely that Trump will simply pull U.S. support, leaving Ukraine to sue for peace and accept whatever terms it can get.

Beyond securing a lasting peace, the United States has two other interests at stake as it drafts its peace plan. The Trump administration has expressed its intent to reduce the U.S. role in Europe’s defense and security architecture. Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth made this clear in his remarks at a meeting of the Ukraine Defense Contact Group in February 2025, saying that “safeguarding European security must be an imperative for European members of NATO.”7Alex Therrien and Frank Gardner, “Hegseth sets out hard line on European defence and Nato,” BBC, February 12, 2025, https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cy0pz3er37jo. Trump’s negotiating team should therefore ensure that any peace arrangement furthers this objective, for instance by assigning to Europe the lead role for supporting Ukraine’s security over the long term and limiting U.S. obligations.8“Michael Hirsh, “Trump’s Plan for NATO Is Emerging,” Politico, July 2, 2024, https://www.politico.com/news/magazine/2024/07/02/nato-second-trump-term-00164517; Alex Velez-Green and Robert Peters, “The Prioritization Imperative: A Strategy to Defend America’s Interests in a More Dangerous World,” Heritage Foundation, August 1, 2024, https://www.heritage.org/defense/report/the-prioritization-imperative-strategy-defend-americas-interests-more-dangerous. Finally, the United States would benefit from stabilizing its relationship with Russia and could use a war settlement to move in this direction.

Because the U.S. stakes in Ukraine are limited, however, Washington should place firm limits on the price it is willing to pay for this “lasting peace” outcome. Offering Ukraine a binding security guarantee would cost the United States far more than its stakes in Ukraine presently justify. Instead, as it seeks a durable peace agreement, Washington should avoid long-term and binding promises that saddle the United States with costly, generational commitments that do not serve its interests.

The United States will likely need to offer incentives to both Ukraine and Russia, not only to get them to the table but to make any agreement last. There are a few sweeteners the United States could put on the table without sacrificing its own interests. To get buy-in from Russia, the U.S. might be willing to compromise on sanctions relief or discuss guardrails on the NATO-Russia relationship, especially along their shared border. With Ukraine, Washington, along with NATO allies, might offer some combination of term- and quantity-limited security assistance, investment dollars, and reconstruction aid. All will be discussed in more detail in the next section.

Critics argue that any deal short of Ukraine’s maximalist position is unacceptable because it does not offer Ukraine a “just peace” or because it does not put Ukraine’s interests first. These complaints are off-base. The “just peace” outcome, as it has been defined, is not achievable. Ukraine simply does not have the military manpower that would be needed to drive Russia back to its 2014 or even 2022 borders, and the United States and much of Europe have ruled out sending military forces to help it do so.9Marc Santora, “Ukraine’s Big Vulnerabilities: Ammunition, Soldiers and Air Defense,” New York Times, April 16, 2024, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/04/16/world/europe/ukraine-war-weapons.html. Moreover, NATO members have already significantly drawn down their weapons stockpiles and their defense production is still too slow to meet Ukraine’s needs.10Natasha Bertrand and Oren Liebermann, “US Military Aid Packages to Ukraine Shrink amid Concerns over Pentagon Stockpiles,” CNN, September 17, 2024, https://www.cnn.com/2024/09/17/politics/us-reducing-military-aid-packages-ukraine/index.html; James Landale, “Ukraine War: Western Allies Say They Are Running Out of Ammunition,” BBC, October 3, 2023, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-66984944.

For its part, Russia is unlikely to accept a deal that it sees as punitive, and neither the United States nor Ukraine can force it to do so at this point. Ukraine’s NATO membership, for instance, is a core part of many “just peace” plan proposals, but it is opposed by both Russian President Vladimir Putin—it was one of the main causes of the war, after all—and key NATO allies like the United States and Germany.11Becky Sullivan, “How NATO’s Expansion Helped Drive Putin to Invade Ukraine, NPR, February 24, 2022, https://www.npr.org/2022/01/29/1076193616/ukraine-russia-nato-explainer; Kimberly Marten, “NATO Enlargement: Evaluating Its Consequences in Russia,” International Politics 57 (2020); Mary E. Sarotte, Not One Inch: America, Russia, and the Making of Post-Cold War Stalemate (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2021).

This does not mean that Ukraine should be forced into a peace settlement that seems like a surrender. Such a deal would likely be short-lived and bring new costs and risks to the United States. Ukraine would have incentives to sabotage an imposed, unfavorable deal, while Russia may be tempted to resume hostilities if it fears Kyiv’s commitment to peace is insincere. However, U.S. negotiators have a responsibility to put U.S. interests over Ukraine’s when working towards peace.

Framework for a lasting deal

Any settlement in Ukraine is likely to be reached through a series of deals, each involving a different set of actors. There are many ways to group the relevant and interrelated issues, but this paper will focus on five main categories: territory; ceasefire terms; arrangements for Ukraine’s future security; stabilizing relationships between Russia and NATO and Russia and the United States; and mutual assurances between Russia and Ukraine. Washington will have some role to play on each of the five issues.

Territory

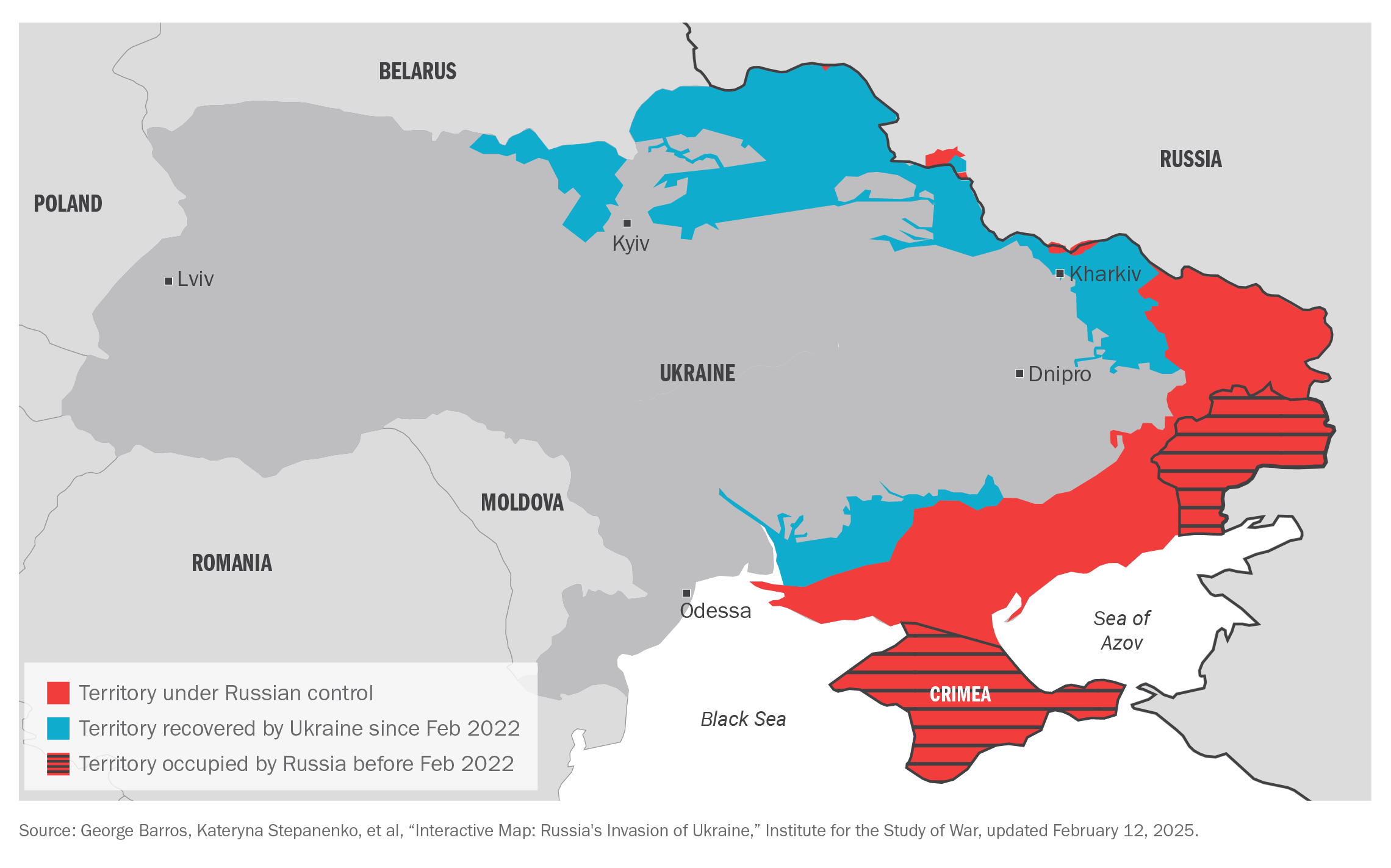

Questions of territory will largely be settled on the battlefield, with de facto Ukrainian borders along the conflict’s front line.12Samuel Charap, “A Pathway to Peace in Ukraine,” Foreign Affairs, December 24, 2024, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/ukraine/pathway-peace-ukraine. This line may move between now and when initial and final ceasefires are concluded, but these changes should be limited if a ceasefire is reached this year. Although Russia has been making slow gains, they have come at very high cost in terms of personnel and military hardware. At points, Russia seemed to be losing as many as 1,500 troops per day.13Alexy Kovalev, “Putin Is Throwing Human Waves at Ukraine But Can’t Do It Forever,” Foreign Policy, November 25, 2024, https://foreignpolicy.com/2024/11/25/russia-ukraine-war-casualties-deaths-losses-soldiers-killed-meatgrinder-attacks/. Moscow has been able to reconstitute its military faster than expected, but it still seems unlikely that Russia will achieve a breakthrough in the near or medium term.14Noah Robertson, “Russian Military ‘Almost Completely Reconstituted,’ US Official Says,” Defense News, April 3, 2024, https://www.defensenews.com/pentagon/2024/04/03/russian-military-almost-completely-reconstituted-us-official-says/.

Territorial control of Ukraine as of February 2025

A peace deal is likely to set a de facto Ukrainian border along the conflict’s front line at the time of ceasefire.

On the Ukrainian side, future offensives seem unlikely, and manpower shortages have left Kyiv’s forces just hanging on. Recent force reorganization plans may help Ukraine’s army do more to stabilize its front lines and further slow any losses, but they are unlikely to result in successful Ukrainian offensives in the east, where Russian forces are dug in.15Valentyna Romanenko, “Ukraine’s Armed Forces Begin Transition to Corps Structure,” Ukrainska Pravda, February 3, 2025, https://www.pravda.com.ua/eng/news/2025/02/3/7496529/; Jamie Dettmer, “Ukraine Is at Great Risk of Its Front Lines Collapsing,” Politico, April 3, 2024, https://www.politico.eu/article/ukraine-great-risk-front-line-collapse-war-russia/. Moreover, although the Trump administration has not officially paused military aid to Ukraine, so shipments set in motion under the Biden administration continue to arrive, neither has it moved to make new commitments or put forward new appropriation requests for additional funds. Ukraine may, as a result, continue to struggle to maintain its current position.16Mike Stone and Erin Banco, “US Arms Shipments to Kyiv Briefly Paused before Resuming over Weekend, Sources Say,” Reuters, February 3, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/world/us-arms-shipments-kyiv-briefly-paused-before-resuming-over-weekend-sources-say-2025-02-03/.

One question mark is the small amount of territory that Ukraine still holds in Kursk, Russia. Putin may be reluctant to come to the bargaining table while this land is in Ukraine’s hands, but if a ceasefire occurs before it is reclaimed, it might open the door for a land swap between Kyiv and Moscow. Trades and small adjustments to the ceasefire line might occur anyway—even if the territory in Kursk is not an issue—to “rationalize” the line, move the border around geographic features or village or city limits, or for other reasons.

These types of swaps are not unheard of. For example, in 2018, Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan arranged for a swap of territories between their two countries as they worked to delineate parts of their border that have remained undefined since the collapse of the Soviet Union.17“Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan Agree To Work on Land Swap near Border,” Radio Free Europe, August 15, 2018, https://www.rferl.org/a/kyrgyzstan-uzbekistan-agree-to-work-on-land-swap-near-border/29435146.html. Swaps are also likely to feature in any future Israeli-Palestinian deal and have been considered as a way to settle the border dispute between India and China.18Ameya Pratap Singh, “The Past (and Future) of the Territorial Swap Offer in the China-India Border Dispute,” Diplomat, July 1, 2024, https://thediplomat.com/2024/07/the-past-and-future-of-the-territorial-swap-offer-in-the-china-india-border-dispute/; Dore Gold, “‘Land Swaps’ and the 1967 Lines,” Jewish Political Studies Review 25, no.1/2 (2013), https://www.jstor.org/stable/23611130.

The United States does not have a direct stake in where Ukraine’s de facto border eventually falls, except that it be largely defensible for Ukraine and acceptable to both sides and that transit through the Black Sea be secure for all actors. It is worth noting that most post-World War II interstate peace settlements have not involved even temporary transfers of territory, instead reestablishing pre-war territorial boundaries by mutual agreement.19Virginia Page Fortna, Peace Time: Cease-Fire Agreements and the Durability of Peace (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004). This is unlikely to be the case in Ukraine and territorial disputes will remain a risk factor going forward. Negotiators should keep this mind when dealing with other issues in any final settlement.

Terms of a ceasefire

The concept of a ceasefire or a cessation of hostilities is simple, but the terms for securing and monitoring it rarely are. Virginia Page Fortna’s book Peace Time makes a convincing case that the way a ceasefire is structured and implemented can have significant implications for a peace treaty’s endurance.20Fortna, Peace Time. She highlights the effects of two provisions especially: demilitarized zones (DMZ) and monitoring regimes (to include peacekeeping forces).

The creation of a full DMZ (in which no military forces or equipment are permitted) substantially increases the endurance of peace in her analysis. Size matters, but more important is that partial DMZs (in which military forces and hardware are restricted in number and kind, but not prohibited) almost always fail.21Fortna, Peace Time. U.S. negotiators should push for a full DMZ between Ukraine and Russia to create a buffer and reduce the chances that skirmishes ignite a new round of war. A buffer would also give each side a bit of breathing room, possibly attenuating the risks of security dilemmas that contribute to escalation and imperil peace.

U.S. negotiators should insist on the creation of a DMZ between Russia and Ukraine, spread equally on each side of the de facto eastern border. The size of the DMZ may depend a bit on where the line of contact falls but generally wider is better for obvious reasons. Historically, DMZs have varied in width from a few thousand yards to over 10 miles. The DMZ on the Korean Peninsula is about 2.5 miles wide while Egypt keeps its military forces about 10 miles from Israel’s border in the Sinai.22Fortna, Peace Time. In Ukraine, a five-mile-wide DMZ along the line of contact, which stretches about 600 miles, would be a good place to start.

To be most effective, DMZ compliance should be monitored on both sides.23Fortna, Peace Time. This could be efficiently done with a small force of unarmed observers combined with drones and sensors. Given the length of the border and likely Russian sensitivities about the presence of foreign forces, negotiators should push for a robust remote monitoring regime as a baseline.24Fortna, Peace Time; Charap, “A Pathway to Peace.” This could be supplemented by on-the-ground observers under an international mandate who could respond to reported violations.

This observer force need not be large or armed. After the Iran-Iraq War ended in 1988, for instance, the almost 900-mile ceasefire line was monitored by 400 military observers (and some civilians) from diverse countries under the United Nations Iran-Iraq Military Observer Group. The mission conducted an average of 64 patrols of different border regions each day, documenting and addressing over 1,000 violations over its four-year lifespan. The observers dealt with violations locally if possible and referred them to higher headquarters in Baghdad and Tehran when necessary. The approach was effective at maintaining the ceasefire at a reasonable cost and without heavily armed personnel.25“Background,” United Nations Iran-Iraq Military Observer Group, accessed February 11, 2025, https://peacekeeping.un.org/mission/past/uniimogbackgr.html. A similar approach could work in Ukraine and would be even more effective if supplemented with sensing and autonomous technology already used to secure borders elsewhere.

An alternative would be to use a more robust peacekeeping force under an international mandate, akin to those that have been employed following long conflicts in the Balkans and Southern Lebanon. Fortna’s book finds mixed results when examining the efficacy of peacekeeping forces, noting that they can contribute to the durability of a ceasefire and rarely work against it, but often have no effect. Differences between armed and unarmed forces are small, with peacekeepers focused on monitoring about as effective as armed troops.26Fortna, Peace Time. Ukraine’s past experience with peacekeeping forces offers reason for pessimism in this case. The Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe Special Monitoring Mission, deployed to Ukraine from 2014 to 2022, was largely a failure. It was not able to ensure that the 2014 ceasefire between Moscow and Kyiv was fully implemented and failed to prevent the 2022 invasion.27Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, “OSCE Special Monitoring Mission to Ukraine,” accessed February 13, 2025, https://www.osce.org/special-monitoring-mission-to-ukraine-closed.

Despite this history, Ukraine’s president Volodymyr Zelensky has suggested that a large peacekeeping force will be required as part of any war settlement, offering 200,000 as the minimum number of personnel required and stating that European and U.S. forces must be included.28Martin Fornusek, “Zelensky Clarifies Comment on 200,000 Peacekeepers, Says Figure Depends on Ukrainian Army Size,” Kyiv Independent, January 23, 2025, https://kyivindependent.com/zelensky-clarifies-comment-on-200-000-peacekeepers/. His request is unrealistic but also seems to conflate the presence of peacekeepers, intended to monitor and enforce the terms of a ceasefire, and the deployment of tripwire or combat-credible deterrent military forces that would respond in kind to renewed Russian aggression as part of a security guarantee.29Steven Erlanger, “Can European ‘Boots on the Ground’ Help Protect Ukraine’s Security?,” New York Times, February 11, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/02/11/world/europe/ukraine-russia-trump.html. Peacekeeping forces are not intended as a first line of defense. They should be neutral and typically operate on carefully delineated rules of engagement.30Fortna, Peace Time; Charap, “A Pathway to Peace.” This would rule out the United States or any European country from contributing to a peacekeeping force, as those forces could not be considered neutral.

If peacekeepers were sent to Ukraine, the force would be small and likely under a UN or other international mandate. Countries in Asia, Africa, and South America may be willing to contribute, but since its founding, the total number of military peacekeepers deployed globally across all UN missions has never been more than 100,000, with typically fewer than 15,000 per location.31George Gao, “UN Peacekeeping at New Heights after Post-Cold War Surge and Decline,” Pew Research Center, March 2, 2016, https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2016/03/02/un-peacekeeping-at-new-highs-after-post-cold-war-surge-and-decline/; Our World in Data, “United Nations peacekeepers on active missions,” accessed February 13, 2025, https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/un-peacekeeping-forces. This is not an impediment to the efficacy of peacekeepers in maintaining a Ukraine-Russia ceasefire, however, especially if supported by technology.

Ukraine’s future security

The third bucket of issues related to Ukraine’s future security may be the most difficult to resolve but also the most important when it comes to achieving a lasting peace. Two issues will dominate this discussion. The first is the question of Ukraine’s security alignment and guarantees, that is whether Ukraine becomes a member of NATO or the EU (both of which come with mutual defense provisions), forms a binding security alliance with the United States (or other country) outside of these organizations, or commits formally to neutrality. The second is what types of security assistance it will receive, including weapons, training, and other support.

Ukraine and Russia disagree on these issues. Ukraine wants immediate NATO membership, which it sees as the most robust security guarantee it could receive. Zelensky has also offered a long list of military equipment he needs from the United States, including longer-range missiles, tanks, and fighter jets. He hopes to have U.S. and European forces deployed inside Ukraine as well, to back up the NATO guarantee and to offer training and support.32Rémy Ourdan and Philippe Jacqué, “Zelensky Pleads for Ukraine NATO Membership, Europeans Look for Another Solution,” Le Monde, December 3, 2024, https://www.lemonde.fr/en/international/article/2024/12/03/zelensky-pleads-for-ukraine-nato-membership-europeans-look-for-another-solution_6735017_4.html; Veronika Melkozerova, “Here’s What’s in Zelenskyy’s Victory Plan for Beating Putin,” Politico, October 16, 2024, https://www.politico.eu/article/volodymyr-zelenskyy-presents-his-victory-plan-to-ukraine-parliament-war-vladimir-putin/. Russia, on the other hand, wants a neutral and demilitarized Ukraine with no military forces, foreign or otherwise, inside its neighbor’s borders.33Andrew Roth, “Russia Issues List of Demands It Says Must Be Met to Lower Tensions in Europe,” Guardian, December 17, 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/dec/17/russia-issues-list-demands-tensions-europe-ukraine-nato?ref=hir.harvard.edu; Serhii Kuzan, “Putin’s Peace Plan is Actually a Call for Ukraine’s Capitulation,” Atlantic Council, January 7, 2025, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/ukrainealert/putins-peace-plan-is-actually-a-call-for-ukraines-capitulation/.

For the United States, however, neither of these options should be acceptable. Instead, U.S. negotiators should push for “armed neutrality” which would have Ukraine delay, pause, or end its EU and NATO membership bids, but then ensure that it is “armed to teeth” with defensive weapons and a large, capable fighting force that can deter Russia or hold off its advances if deterrence fails.34Jennifer Kavanagh and Christopher McCallion, “Armed Neutrality for Ukraine Is NATO’s Least Poor Option,” War on the Rocks, February 18, 2025, https://warontherocks.com/2025/02/armed-neutrality-for-ukraine-is-natos-least-poor-option/; Eugene Rumer, “Neutrality: An Alternative to Ukraine’s Membership in NATO,” Council on Foreign Relations, January 7, 2025, https://www.cfr.org/article/neutrality-alternative-ukraines-membership-nato.

Extending NATO membership to Ukraine, along with the Article 5 guarantee, would not be in U.S. interests. It would also be a deal-breaker for Russia, which would almost certainly keep fighting rather than surrender Ukraine to NATO—preventing just such an outcome was one of Russia’s major reasons for starting the war in the first place.35Joshua Shifrinson, “Why NATO Should Be Cautious about Admitting Ukraine,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, July 24, 2023, https://carnegieendowment.org/posts/2023/07/why-nato-should-be-cautious-about-admitting-ukraine?lang=en. Washington’s interests at stake are not high enough to warrant a mutual defense commitment through NATO or in a bilateral arrangement given the military and financial burdens and risks that such a commitment would entail.

The United States has made clear in words and actions that it does not see Ukraine as a national security imperative and has twice refused to send U.S. troops to defend Ukraine. As President Barack Obama admitted in 2016, Russia will always care more about Ukraine than the United States and so will always win the balance of resolve.36Goldberg, “The Obama Doctrine.” Simply extending a security guarantee to Ukraine cannot create a vital interest or reverse this balance.

Importantly, because the United States has declined to defend Ukraine in the past, any future commitment to do so inside or outside of NATO will lack credibility, increasing the risk of deterrence failure unless the U.S. is willing to contribute a sizeable military force to Ukraine to serve as a tripwire and first line of defense.37Benjamin Friedman, “Neutrality Not NATO: Assessing Security Options for Ukraine,” Defense Priorities, July 12, 2023, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/neutrality-not-nato-assessing-security-options-for-ukraine/. This should be a redline, not only because it would further elevate the risk of entanglement in a direct and costly war with Russia, but because the military burden of even a tripwire deployment far exceeds the U.S. stakes and places additional commitments on an already overstretched U.S. military.

Beyond the U.S.-specific consequences, extending NATO membership to Ukraine would have negative consequences for the alliance. NATO, too, has refused to put its military forces on the frontline to defend Ukraine, so it would suffer the same credibility challenges as the United States. Worse, making an uncredible mutual defense promise to Kyiv would call into question the fundamental credibility of the Article 5 provision as it pertains to other NATO members, especially those on NATO’s eastern flank. In other words, adding Ukraine as a member would not make the alliance stronger and might instead deal its foundational pillar a fatal blow.38“At NATO’s Summit, the Alliance Should Not Move Ukraine Toward Membership,” Politico, https://www.politico.com/f/?id=00000190-7a1f-db0b-a39e-fa5fbcdb0000.

Finally, a security guarantee to Ukraine would be antithetical to the U.S. hope that it can draw down its involvement in European security. Instead, it would likely need to ramp up its presence. If Ukraine were included in NATO, at least as currently structured, the bulk of the military obligation during peacetime and wartime would likely fall to the U.S. military, given that it has the most capacity of all NATO members and it is the only military force that Russia takes seriously.39Ben Barry et al., “Defending Europe: Scenario-Based Capability Requirements for NATO’s European Members,” International Institute for Strategic Studies, May 10, 2019, https://www.iiss.org/research-paper//2019/05/defending-europe. European forces might be involved, but it is unlikely they could maintain a sizeable forward presence in Ukraine without the support of U.S. enablers. The United States would thus need to keep ground forces in Europe to underwrite its new commitment.

Limited European military capacity is one reason that a separate European-backed security guarantee to Ukraine—a proposal made by National Security Advisor Mike Waltz and Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth—would not work.40Alexandra Marquez, “Trump’s National Security Adviser: ‘I Don’t Think There’s Any Plans to Invade Canada,’” NBC News, February 9, 2025, https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/donald-trump/trump-national-security-adviser-no-plans-invade-canada-waltz-rcna191374; Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth, “Opening Remarks by Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth at Ukraine Defense Contact Group,” Brussels, Belgium, February 12, 2025, https://www.defense.gov/News/Speeches/Speech/Article/4064113/opening-remarks-by-secretary-of-defense-pete-hegseth-at-ukraine-defense-contact/. Though they might in the future, the Europeans currently cannot credibly back up a security guarantee to Ukraine. They can’t deploy sufficient forces or sustain them in the event of a conflict, without U.S. support.41Barry Posen, “Europe Can Defend Itself,” Survival vol 20, no. 6, December 2020, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00396338.2020.1851080; Mike Sweeny, “How Would Europe Defend Itself,” Defense Priorities, April 11, 2023, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/how-would-europe-defend-itself/. They also have shown little urgency in their response since 2022, raising questions about the reliability of any commitment they might make.

There are other reasons a European security guarantee would not be in U.S. interests. Most important among them are the challenges that would arise if European NATO members offered a mutual defense commitment to Ukraine—either through the EU (Article 42.7 of the Lisbon Treaty offers a mutual defense commitment to members) or through other means—and sent a military force to Ukraine that was subsequently attacked.42“Treaty of Lisbon Amending the Treaty on European Union and the Treaty Establishing the European Community,” art. 42.7, Dec. 13, 2007, O. J. (C 306), https://www.europarl.europa.eu/meetdocs/2009_2014/documents/sede/dv/sede200612mutualdefsolidarityclauses_/sede200612mutualdefsolidarityclauses_en.pdf.

Although such a deployment would fall outside the Article 5 mandate (and although Article 5 does not require member states to respond with armed forces to all acts of aggression), there would still be considerable pressure for a response that could pull the United States into war.43“Collective Defence and Article 5,” North Atlantic Treaty Organization, July 4, 2023, https://www.nato.int/cps/ie/natohq/topics_110496.html. To prevent this outcome, NATO would have to put in place a rigid firewall to rule out a response to deployments outside its mandate. These carveouts would, however, create uncertainty about the credibility of the NATO guarantee, devaluing the alliance and its deterrence.

U.S. negotiators, therefore, should warn Europe against offering an independent security guarantee to Ukraine. The ultimate U.S. goal should be to turn responsibility for supporting Ukraine over to Europe, but this handoff should occur within the framework of an armed neutrality. That would mean European states using security assistance to help Ukraine build its own credible deterrent.

A final suggestion floated by some Ukraine supporters is a semi-formal commitment, more along the lines of the Memorandum of Agreement (MOA) signed with Israel after the Yom Kippur War. This would also be a risky move for the United States. Most importantly, like a formal commitment, an informal arrangement would likely be enduring, creating long-term obligations that exceed the U.S. interests at stake. With Israel, for example, almost 50 years after the MOA was signed, the United States continues to offer $4 billion in Foreign Military Financing (FMF) per year and to support Israel with massive deployments of military force when the small country is threatened.44“Memorandum of Agreement between the Governments of Israel and the United States,” in Foreign Relations of the United States, 1969-1976, Volume XXVI, Arab-Israeli Dispute, 1974-1976, ed., Adam M. Howard (United States Government Printing Office, 2011) https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1969-76v26/d227; Daniel B. Shapiro, “Let’s Talk about the Next US-Israel Military-Assistance Agreement,” Defense One, January 31, 2025, https://www.defenseone.com/ideas/2025/01/next-us-israel-mou/402674/. In 2024, the United States participated actively in Israel’s air defense, and had Iranian retaliation over Israeli strikes against Hezbollah continued, the United States might have participated even more directly in reprisals.

A similar commitment to Ukraine would have an expanded set of risks, as it could easily bring the United States into direct conflict with Russia and its large nuclear stockpile. The issue of credibility is also relevant here. The United States has declined to offer Ukraine the support it has given to Israel over the past 18 months for a reason—not the lack of an agreement but the lack of a compelling vital interest.45Agence France Presse, “Zelensky Calls for Same ‘Unity’ from Allies as for Israel,” Barron’s, April 15, 2024, https://www.barrons.com/news/zelensky-calls-for-same-unity-from-allies-as-for-israel-9558c12b. Friedman, “Neutrality not NATO.” Thus, a semi-formal commitment to Ukraine would be a hollow commitment that would leave Ukraine more exposed rather than more secure. At the same time, even lacking in credibility, such a commitment would create new risks for the United States, including raising questions about the reliability of other U.S. security guarantees and creating pressure for more U.S. military support to Ukraine and retaliation if Kyiv were attacked again.46“Ukraine Deserves to Become NATO’s 33rd Member – Volodymyr Zelenskyy During Meeting with Mark Rutte,” President of Ukraine, October 17, 2024, https://www.president.gov.ua/en/news/ukrayina-zaslugovuye-stati-33-m-chlenom-nato-volodimir-zelen-93913#.

To counter these arguments against security guarantees in their various forms, Ukraine’s supporters have suggested that it “deserves” an ironclad commitment from the United States and Europe after three years of war.47Fortna, Peace Time. But security guarantees are not given out for good behavior; they are based on national interests. In fact, it is uncommon for external parties to offer such commitments as part of peace settlements. The United States used a guarantee of sorts to help settle the Yom Kippur war, and it offered South Korea a mutual defense commitment some months after the armistice on the Korean Peninsula. But especially since World War II, there are few examples of the type of guarantee Ukraine is hoping for as a condition of a peace settlement.

There is no security guarantee to Ukraine that is consistent with U.S. interests, whether provided by NATO, Washington, or Europe. The Trump administration should advocate instead for Ukraine’s neutrality, leaving it outside NATO permanently or for an extended period. EU membership should also be deferred to a later date. NATO members may be unwilling to formally shut the door on Ukraine, as they have long refused to give Russia a veto over the alliance’s membership.48Patrick Reevell and Conor Finnegan, “NATO Rejects Russian Demands for Security Guarantees in Latest Round of Talks,” ABC News, January 12, 2022, https://abcnews.go.com/International/nato-rejects-russian-demands-security-guarantees-latest-round/story?id=82226913; “NATO-Russia Founding Act,” The White House, May 15, 1997, https://1997-2001.state.gov/regions/eur/fs_nato_whitehouse.html#:~:text=The%20Act%20makes%20clear%20that,no%20impact%20on%20NATO%20enlargement. For its part, Russia is unlikely to accept an informal commitment to limit Ukraine’s NATO membership, given what it sees as Western violations of past promises regarding NATO expansion.49Mary Elise Sarotte, “A Broken Promise? What the West Really Told Moscow about NATO Expansion,” Foreign Affairs, August 11, 2014, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/russia/broken-promise-nato; Sarotte, Not One Inch. Instead, Kyiv could write neutrality into its constitution—or make some other sort of lasting commitment—as part of a broader political settlement and in return for security assistance from the West and assurances from Moscow.50“Declaration of State Sovereignty of Ukraine,” Government of Ukraine, July 16, 1990, https://static.rada.gov.ua/site/postanova_eng/Declaration_of_State_Sovereignty_of_Ukraine_rev1.htm.

While insisting on neutrality, the United States and its NATO partners should not leave Ukraine entirely defenseless as this would raise the risk of renewed conflict, an outcome that the U.S. hopes to avoid. Instead, the United States and NATO allies should commit to work with each other and Ukraine to make sure that Ukraine is able to build a credible deterrent force capable of defending itself without assistance.

Putting Ukraine in a position to defend itself will not be easy, but it is entirely achievable with a short- and medium-term commitment from the United States, a long-term commitment from Europe, and investment in Ukraine’s defense industrial base so that it can defend itself. Although the United States would likely have to play a significant role in arming Ukraine in the near term, as Europe’s defense production comes online, the Europeans should take the lead and most of the responsibility for the medium- and longer-term. To ensure Europe stays on track, the United States can set a timeline for phasing out its military support or make its military aid to its NATO allies contingent on their defense investment. Other emerging defense producers like South Korea can also be counted on to speed the process of arming Ukraine.

Current U.S. and European defense stockpiles are depleted, and defense industrial production is slow, but Ukraine does not need to be fully armed overnight. Russia will also need time to rebuild, so Ukraine’s partners likely have five to 10 years to help it establish a self-sustaining defense.51Dara Massicot, “Russian Military Reconstitution: 2030 Pathways and Prospects,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, September 12, 2024, https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2024/09/russian-military-reconstitution-2030-pathways-and-prospects?lang=en; Michelle Grisé, Russia’s Military after Ukraine: Potential Pathways for the Postwar Reconstitution of the Russian Armed Forces (Washington: RAND Corporation, 2025) https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RRA2700/RRA2713-1/RAND_RRA2713-1.pdf. Early tranches of aid should focus on basic defensive capabilities that the United States still has or can easily produce in bulk, for example, anti-tank and anti-personnel mines; cement and fencing to build barriers, dragon’s teeth, trenches, and other obstacles; short-range artillery systems and some anti-tank ammunition; and short-range munitions like Guided Multiple Launch Rocket Systems (GMLRS) and Joint Direct Attack Guided Munitions (JDAM).52Jennifer Kavanagh, “A Defensive Approach to Ukraine Military Aid,” Defense Priorities, November 6, 2024, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/a-defensive-approach-to-ukraine-military-aid/. These capabilities will allow Ukraine to set up a well-fortified, layered defensive line, one that would be difficult and costly for Russia to break through.53Emma Ashford and Kelly A. Grieco, “How Ukraine Can Win through Defense,” Foreign Affairs, January 10, 2024, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/ukraine/how-ukraine-can-win-through-defense. Although Ukraine has already made some of these investments, there is much more that it can do to support its ability to deter renewed Russian attacks.

Not on this list is aircraft or other largely offensive capabilities, like intermediate- and longer-range missiles. Ukraine is already slated to receive about 80 F-16s from NATO partners and likely would not need a larger air force for defensive operations.54Paul B. Stares and Michael O’Hanlon, “Defending Ukraine in the Absence of NATO Security Guarantees,” Council on Foreign Relations, January 2025, https://www.cfr.org/report/defending-ukraine-absence-nato-security-guarantees; Christopher Koeltzow, Brent Peterson, and Eric Williams, “F-16s Unleashed: How They Will Impact Ukraine’s War,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, June 11, 2024, https://www.csis.org/analysis/f-16s-unleashed-how-they-will-impact-ukraines-war; “How Much of a Difference Will Ukraine’s New F-16s Make?” Economist, August 4, 2024, https://www.economist.com/europe/2024/08/04/how-much-of-a-difference-will-ukraines-new-f-16s-make. There are also reasons that that the United States might intentionally restrict Ukraine’s access to U.S.-made, longer-range missiles. Such weapons could reach deeper inside Russia and provoke legitimate security concerns in Moscow that would work against an enduring peace.55Fabian Hoffmann, “Strategic Stability and the Ukraine War: Implications of Conventional Missile Technologies,” Center for Naval Analyses, February 2024, https://www.cna.org/reports/2024/02/strategic-stability-and-the-ukraine-war-implications-of-conventional-missile-technologies. Ukraine does not need to be able to launch offensive operations but rather to demonstrate that it can inflict costs and deny Russia its strategic objectives if it renews military aggression in the future.

Ukraine will also need air defense systems and missiles, including short-range Stingers and more advanced Patriot systems, to protect military assets and civilian infrastructure. These are “high demand, low density” systems and global shortages are severe, so Ukraine will need to rely on multiple sources and build a stockpile over time.56Nancy A. Youssef and Gordon Lubold, “Pentagon Runs Low on Air-Defense Missiles as Demand Surges,” Wall Street Journal, October 29, 2024, https://www.wsj.com/politics/national-security/pentagon-runs-low-on-air-defense-missiles-as-demand-surges-7fc9370c; Kavanagh, “A Defensive Approach.” Later aid packages might include some air-to-air munitions that can be used to support air defense; command and control systems; armored vehicles (Bradley Fighting Vehicles have been especially useful in Ukraine); anti-ship missiles to guard Ukraine’s coast; and uncrewed air and sea vessels and cyber capabilities.

In addition to military assistance, the United States and Europe should invest in Ukraine’s defense sector and encourage private companies to do the same. After all, Ukraine was a leading hub of defense production during the Soviet days.57Barry Posen, “Barry Posen’s 1994 Defense Concept for Ukraine,” MIT Security Studies Program, accessed February 11, 2025, https://ssp.mit.edu/publications/2022/a-1994-defense-concept-for-ukraine. Despite the ongoing war, Ukraine’s defense industry is already growing rapidly, especially its drone production which exceeds that of even the United States in speed of innovation and production.

By the end of 2024, Ukraine was producing 2.5 million mortar and artillery rounds of different calibers, along with about 1.5 million drones, a growing number of armored vehicles, and its own long-range missiles and air defense systems.58“Fact Sheet on Efforts of Ukraine Defense Contact Group National Armaments Directors,” U.S. Department of Defense, January 10, 2025, https://www.defense.gov/News/Releases/Release/Article/4026238/fact-sheet-on-efforts-of-ukraine-defense-contact-group-national-armaments-direc/#; “Ukraine’s Long-Term Path to Success: Jumpstarting a Self-Sufficient Defense Industrial Base with US and EU Support,” Institute for the Study of War, January 14, 2024, https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/ukraine%E2%80%99s-long-term-path-success-jumpstarting-self-sufficient-defense-industrial-base; Abbey Fenbert, “Ukrainian Drones Made Up over 96% of UAVs Military Used in 2024, Defense Minister Says,” Kyiv Independent, December 28, 2024, https://kyivindependent.com/ukrainian-drones-made-up-over-96-of-uavs-military-used-in-2024-defense-minister-says/. Ukraine has also set up a number of private-sector defense partnerships between indigenous and foreign firms to support production of equipment like air defense, longer-range munitions, and 155mm ammunition.59Valerie Insinna, “Northrop Planning to Build Munitions inside Ukraine,” Breaking Defense, June 18, 2024, https://breakingdefense.com/2024/06/northrop-planning-to-build-munitions-inside-ukraine/; Abbey Fenbert, “Ukraine Developing Its Own Air Defense System to Combat Russia’s ‘Oreshnik,’ Syrskyi Says,” Kyiv Independent, January 19, 2024, https://kyivindependent.com/ukraine-producing-its-own-air-defense-systems-syrskyi-says/. Ultimately, this ability to resupply itself will be crucial for Ukraine’s long-term defense self-sufficiency.

Ukraine will also need a large standing army with a sizeable reserve force and smaller numbers of air force and naval personnel. Using campaign analysis, Michael O’Hanlon and Paul Stares estimate Ukraine would need a military force of around one million soldiers to ensure its defense in the case of renewed Russian aggression, split between active duty and reserve forces.60Stares and O’Hanlon, “Defending Ukraine.” They calculate that a force of 500,000–600,000 would be needed as a frontline defense along the entirety of Ukraine’s border with Russia in the event of a Russian attack.

Ukraine would also need a surge force to supplement these forces in the event of a Russian offensive push. O’Hanlon and Stares estimate about 150,000 troops will be needed, able to match Russia’s troop surges during the war. Of these 650,000–750,000 forces, 300,000 might be kept on active duty (a mix of conscripts and professional soldiers) and the remainder would form a high-readiness reserve. To this, Ukraine might add air and missile defense and cyber forces, totaling 50,000, and an institutional army to manage training and acquisition of a similar size. Finally, Ukraine would need a small air force and navy, which O’Hanlon and Stares put at 100,000 personnel, though fewer might suffice.61Stares and O’Hanlon, “Defending Ukraine.” This would leave Ukraine with an active-duty force of up to 500,000 (smaller than the number Ukraine says it has activated currently) and a reserve of about 450,000. Given Ukraine’s shrinking population and low birth rates this will be challenging, but it is not impossible, especially over an extended period. Military assistance from Europe might be used to fund soldier salaries and recruiting incentives.62Elissa Nadworny and Claire Harbage, “Ukraine’s birth rate was already dangerously low. Then war broke out,” All Things Considered, NPR, February 22, 2023, https://www.npr.org/2023/02/22/1155943055/ukraine-low-birth-rate-russia-war.

Skeptics of the armed neutrality approach argue that it leaves Ukraine “defenseless.”63Timothy Ash et al., “How to End Russia’s War on Ukraine: Safeguarding Europe’s Future, and the Dangers of a False Peace,” Chatham House, June 2023, https://chathamhouse.soutron.net/Portal/Public/en-GB/DownloadImageFile.ashx?objectId=7024&ownerType=0&ownerId=203336. As the discussion above suggests, this is far from the case. There are good historical precedents for the success of armed neutrality. Finland is the most frequently cited example. At the end of the Winter and Continuation Wars, Finland’s military weakness forced it to accept Soviet-imposed neutrality, preventing it from joining NATO or the EU as Europe recovered after World War II.64Walter Z. Laqueur, “Europe: The Specter of Finlandization,” Commentary, December 1977, https://www.commentary.org/articles/walter-laqueur/europe-the-specter-of-finlandization/; Olli Vehvilainen, Finland in the Second World War: Between Germany and Russia, trans. Gerard McAlester (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2002). Finland, however, remained independent and was able to build a formidable deterrent force that allowed it to retain its sovereignty throughout the Cold War, despite sharing a long border with a formidable Soviet Union, and enjoy political freedoms and economic prosperity similar to its Western neighbors.65Roy Allison, Finland’s Relations with the Soviet Union, 1944-84 (New York: Macmillan, 1985); Paul R. S. Gebhard, “For Finland, the Cold War Never Ended. That’s Why It’s Ready for NATO,” Atlantic Council, May 20, 2022, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/for-finland-the-cold-war-never-ended-thats-why-its-ready-for-nato/. Its success is a testament to the promise of armed neutrality, especially when combined with the national will to fight and efforts to balance deterrence with reassurance. Ukraine already has the first and can achieve the second with a well-constructed political settlement, as outlined here.66Tomas Ries, Cold Will: The Defense of Finland (Brassey’s Defence Publishers, 1988).67Kenneth N. Waltz, Theory of International Politics (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1979).

Armed neutrality for Ukraine best serves the interests of the United States and NATO. It minimizes the new commitments and security burdens each must take on and appropriately aligns the risks and costs incurred with the stakes involved. The United States and NATO will still need to find the resources to sufficiently arm Ukraine, and as noted above, this obligation will fall primarily to Europe. Armed neutrality also protects the credibility of the Article 5 guarantee to current members. Counterintuitively, armed neutrality is also the best chance Ukraine has at a lasting peace. True, it would be fully responsible for its own defense and would have no backup, but it would receive significant support to achieve its self-sufficiency and have autonomy over its own security policy. Moreover, history has shown time and again that the only true security guarantee is the one a country provides itself.

Neither Ukraine nor Russia is likely to be fully satisfied with the armed neutrality approach. U.S. negotiators should be clear that formal mutual defense commitments would not offer Ukraine the security it is hoping for and would be riddled with credibility issues. They might even heighten the risk of long-term conflict by inflaming Russian threat perceptions. Article 5 is also not automatic, and allies have wide discretion about how and when to use military force, a fact that should give Kyiv pause.68Rumer, “Neutrality: An Alternative to Ukraine’s Membership in NATO.”

To partially assuage Kyiv’s fears, the United States might commit as part of a settlement to providing up to a certain amount of military assistance for up to five or so years, assuming Ukraine sticks to the terms of the agreement. But U.S. negotiators should avoid long-term commitments like that given to Israel. Recently, President Trump has expressed interest in doing a deal with Ukraine regarding its rare earth minerals which could be lucrative if developed, but the terms of such an agreement remain unclear.69“Trump Says He Wants Ukraine to Supply US with Rare Earths,” Reuters, February 4, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/trump-says-he-wants-ukraine-supply-us-with-rare-earths-2025-02-03/. Washington could work out an arrangement where Ukraine compensates the United States for any security assistance through access to the country’s rare earths, but rare earth mineral income could also be used to finance Ukraine’s reconstruction. The details could be addressed outside of the peace settlement.

Russia, in contrast, will have concerns about U.S. and Western military aid to Ukraine. In dealing with Russian resistance, the United States should be willing to discuss term and quantity limits on its assistance, as well as ruling out certain types of systems like intermediate-range missiles or activities like multinational exercises inside Ukrainian territory. The two sides should also agree to keep Ukraine as a non-nuclear power. Finally, the United States might offer Russia sweeteners for compromising on aspects of Ukraine’s security, including discussing the U.S. role in Europe’s security architecture or some sanctions relief, discussed in more detail in the next section.

Stabilizing U.S. and NATO relationships with Russia

For Russia, the war in Ukraine is not just about Ukraine or its territory, but about the security architecture in Europe and NATO’s seemingly inexorable advance eastward. In two December 2021 treaty drafts shared with the United States and other NATO members, Russia laid out a series of demands, including: limits on additional NATO expansion, especially to Ukraine; a ban on the deployment of NATO forces and weapons in territories that joined the alliance after 1997; geographic restrictions on the basing of intermediate-range missiles and the operations of warships and heavy bombers; and a ban on NATO military activities in Eastern Europe, the Caucasus, and Central Asia.70Robyn Dixon and Paul Sonne, “Russia Broadens Security Demands from West, Seeking to Curb U.S. and NATO Influence on Borders,” Washington Post, December 17, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2021/12/17/ukraine-russia-military/; Andrew E. Kramer and Steven Erlanger, “Russia Lays Out Demands for a Sweeping New Security Deal with NATO,” New York Times, December 17, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/12/17/world/europe/russia-nato-security-deal.html.

The United States and NATO leaders rejected these demands at the time, though then-national security advisor Jake Sullivan indicated that the United States and Europe had their own lists of security concerns and that they would be willing to negotiate on that mutual basis.71“White House’s Sullivan says US prepared for Dialogue with Russia,” Reuters, December 17, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/world/white-houses-sullivan-says-us-prepared-dialogue-with-russia-2021-12-17/. Two months later, Russia launched its invasion of Ukraine.

These core issues are among the best leverage the United States has when it comes to getting Russia to the table and concluding an agreement, but they also offer an opportunity for exploring ways to stabilize U.S. and NATO relations with Russia.

The Trump administration should be willing to use the future U.S. role in Europe as a bargaining chip to a much greater extent than the Biden team. Addressing these issues is less imperative to achieving an end to the fighting in Ukraine than concerns about territory, the ceasefire, and Ukraine’s future security. Trying to come to terms with Russia on the shape of Europe’s long-term security architecture could overcomplicate negotiations and slow or impede a peace deal. At the same time, a U.S. willingness to have serious discussions about the future of the NATO-Russia and U.S.-Russia relationships could be the carrot that gets Putin to the bargaining table and willing to make concessions of his own. For its part, the United States gives up little by agreeing to talk and does not need to conclude bargaining with Russia over these broader issues at the same time that a ceasefire or narrower peace treaty with Ukraine is concluded.

To balance these conflicting considerations, the Trump administration should follow three guidelines. First, it should indicate to Putin that its openness to changes in its military footprint in Europe will be most expansive if Russia agrees to a ceasefire quickly, using its leverage to accelerate the end of the hot war. Second, although there will be a need for discussions that include the United States, Russia, and its European partners, the United States should be willing to engage in bilateral negotiations on issues pertaining specifically to U.S. forces and weapons. Third, the United States should put its own interests first in these discussions and make Russian reciprocity the baseline for any concessions. Washington should not sell out its European partners, but U.S. and European interests are not the same. The United States has long expressed a desire to burden-shift the responsibilities for Europe’s defense to the continent itself, and it should be willing to use settlement talks with Russia toward this end, even if Europe objects. Drawing down U.S. forces in Europe may be on Putin’s wish list but it is also in U.S. interests.

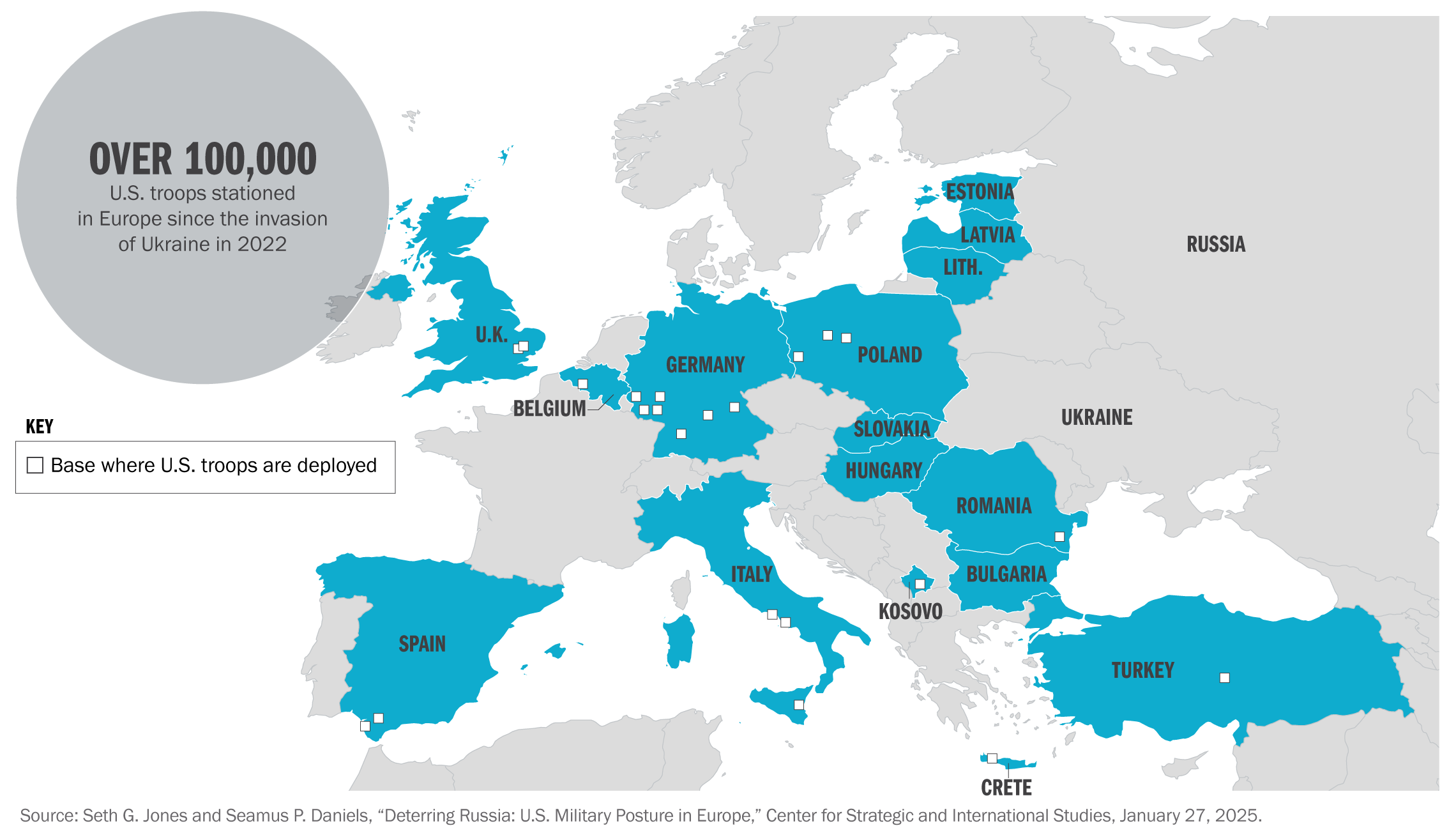

U.S. forces based in Europe (as of February 2025)

In addition to a settlement of the war, Russia and the United States might agree to mutual geographic restrictions on the locations of their armed forces, with both sides pulling back from the NATO-Russia border.

Such a move would allow the United States to conserve scarce military resources; better align its spending and force structure to the higher priority Indo-Pacific theater; and reduce the risk of entanglement in European wars that do not advance U.S. security. In other words, pulling back from Europe would better match U.S. defense spending and strategy to its interests. Moreover, Europe is now wealthy and technologically sophisticated enough to build elite miliary forces, should it choose to do so. The United States does not want to see Europe fall into Russian hands, of course, but this can be prevented with a much smaller (or no) U.S. commitment if Europe steps up to assume full responsibility for its own security. Reducing U.S. military presence in the region would have the additional benefit of communicating clearly to the Europeans that the United States would not be around as a backstop forever.72Velez-Green and Peters, “The Prioritization Imperative”; Austin J. Dahmer, “Resourcing the Strategy of Denial: Optimizing the Defense Budget in Three Alternative Futures,” Marathon Initiative, February 1, 2023, https://themarathoninitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/FINAL_Resourcing-the-Strategy-of-Denial_Dahmer.pdf.

The United States should be willing to put some modifications to its forward posture and activities in Europe on the table in discussions with Russia as they are changes that many national security analysts and the Trump administration have discussed for some time. By pushing for mutual commitments, not unilateral concessions, Washington can get additional benefits from Russia for changes it would like to make anyway.

As a starting point, the United States should offer to remove U.S. military forces from territories that joined NATO after 2000—for permanent and rotational deployments and exercises—in return for a Russian commitment to keep its forces 100 miles (or some other agreed upon distance) from the land border of any NATO country, with comparable provisions made for Russian and U.S. ships that might be operating in the Baltic Sea. This would not give Russia the pre-1997 restriction that it asked for in December 2021, but it would pull U.S. forces out of NATO’s easternmost territories—something that would be consistent with the U.S. desire to reduce its military footprint and defense responsibility in Europe. Any mutual arrangement that is reached along these lines would increase Europe’s security even as it pulled back U.S. forces by increasing the buffer between NATO territory and Russian forces.

Discussions about geographic limits on the location of U.S. and Russian long-range strike capabilities would also be advantageous for both sides, as the end of the Intermediate Range Nuclear Forces (INF) has threatened to create new instability in the region, especially as the United States announced an intention to deploy Tomahawk Land Attack missiles in Germany.73“NATO-Russia Founding Act”; Xiaodon Liang, “U.S. to Deploy Intermediate-Range Missiles in Germany,” Arms Control Association, September 2024, https://www.armscontrol.org/act/2024-09/news/us-deploy-intermediate-range-missiles-germany#. “NATO-Russia Founding Act.” Limiting the locations of these missiles by both Russia and the United States would be a positive development for European security. Reaching an agreement on this issue might take longer than a settlement to end the Ukraine war but initiating the conversation as part of peace talks would make sense.

These moves focus narrowly on U.S. forces and not the changes in NATO deployments Russia requested, but Putin has made clear that it is the United States’ military presence along Russian borders that he finds most objectionable. There are also issues between Russia and NATO that should be considered in any settlement. Though the United States should include European partners in these talks, Washington has significant leverage when it comes to what NATO partners will ultimately agree to.

First, the two sides should reaffirm their commitment to the 1997 NATO-Russia Founding Act, which aimed to set a new foundation for the relationship between NATO and Russia in the post-Cold War period. It included the formation of additional diplomatic channels and a series of military provisions to prevent future conflicts, including the commitment by NATO not to permanently station its forces in the territory of any new alliance members.74“NATO-Russia Founding Act.” Second, the United States should push for mutual geographic restrictions on non-U.S. NATO (U.S. forces would be excluded under provisions discussed above) and Russian military exercises conducted near the NATO-Russia shared border, as well as mutual caps on the number of non-U.S. NATO (U.S. forces would be removed from these territories under provisions discussed above) and Russian military forces deployed near shared borders.

Finally, the United States should work to open discussions (though probably not conclude given the time it might take to reach agreement) about a new version of the now-lapsed Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe (CFE) that would place limits on the number of military forces and conventional capabilities NATO and Russia could maintain more broadly.75Daryl Kimball, “The Conventional Armed Forces in Europe (CFE) Treaty and the Adapted CFE Treaty at a Glance,” Arms Control Association, November 2023, https://www.armscontrol.org/factsheets/conventional-armed-forces-europe-cfe-treaty-and-adapted-cfe-treaty-glance. A revised version of this treaty might limit restrictions on forces and capabilities to border territories if that made agreement easier to reach in the near term. Although these changes would be more conciliatory toward Moscow than some would like, they would push Russian forces back from Europe’s borders offering NATO partners more security, not less. If Russia were to violate the terms by encroaching on NATO territory, then NATO partners could respond in kind.

There is no guarantee that Russia would be open to these proposals, and it is possible that negotiations will lead to alternative compromises. Putting aside the specifics, a good faith U.S. willingness to hold discussions on these topics would be a win for Russia. U.S. negotiators, for their part, should be open to considering any set of terms that supports the overriding U.S. goals of a lasting peace and drawing down its role in Europe, without undermining Europe’s security.

If security issues alone don’t bring Russia to the table or to an agreement, the United States also has economic leverage, in particular through sanctions relief. Removing sanctions on Russia will be an important way to stabilize U.S.-Russia relations and to reintegrate Russia into the world economy. Some would argue that the sanctions regime should stay in place and U.S. policy should continue to try to isolate Russia from the world, but this is not realistic or desirable. Russia is too big a country to be ostracized as the United States has done to North Korea. Sanctions relief could be done in phases and tied to Russia’s compliance with other parts of the settlement. Washington might still choose to keep some sanctions in place.

At the end of Biden’s time in the White House, his administration classified many of the U.S. sanctions on Russia under the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA), which makes it harder to remove them but not impossible.76“Countering America’s Adversaries through Sanctions Act – Related Sanctions,” Office of Foreign Assets Control, accessed February 11, 2025, https://ofac.treasury.gov/sanctions-programs-and-country-information/countering-americas-adversaries-through-sanctions-act-related-sanctions. To lift sanctions under CAATSA, the president must notify Congress, and if Congress does not approve, it must issue a join resolution of disapproval that passes both the House and the Senate. The president can then veto this resolution, and Congress must override the veto with a two-thirds majority in both chambers. Only a handful of times has Congress been able to successfully stop a presidential action through this process.77“Congressional Review Act: Overview and Tracking,” National Conference of State Legislatures, January 28, 2025, https://www.ncsl.org/state-federal/congressional-review-act-overview-and-tracking. The chances are good, then, that if the Trump administration chose to lift sanctions on Russia, it would be able to do so.

There is also the question of the $300 billion in Russian assets frozen by Western, mostly European banks. At least in the initial settlement, these assets should remain frozen. If Russia’s relations with the West and Ukraine stabilize, then this issue could be revisited, but continuing to hold them offers the United States and its NATO allies some continued leverage over Putin and a way to incentivize compliance or retaliate for agreement violations. For now, money earned as interest on the $300 billion is being used as collateral for a loan to Ukraine.78“Parliament Approves up to €35 Billion Loan to Ukraine Backed by Russian Assets,” European Parliament, October 22, 2024, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/press-room/20241017IPR24736/parliament-approves-up-to-EU35-billion-loan-to-ukraine-backed-by-russian-assets. If continued, this could generate initial money for post-war reconstruction in Ukraine. More funds will be needed but much of that money can come from private investment and does not need to be included in the U.S.-Russia or NATO-Russia negotiations.

Sanctions relief alone won’t get Russia to stop fighting—just as piling on more sanctions is unlikely to weaken Putin’s resolve. But a plan for reducing punitive measures placed on Russia during the war should be part of any post-war future because it is hard to see how U.S.-Russia ties can stabilize while they are still in place.

Ukraine-Russia mutual assurances

The final set of issues that the United States should address to secure a peace that is lasting includes mutual assurances between Ukraine and Russia, in particular on security issues. Because neither side is getting what it wants when it comes to Ukraine’s long-term defense posture (NATO membership for Kyiv and Ukraine’s demilitarization for Moscow), there will continue to be some insecurity on both sides. A history of distrust and perceived broken promises will further complicate the Russia-Ukraine relationship going forward. Mutual assurances can help overcome this distrust, and Fortna’s research confirms their efficacy in increasing the endurance of peace settlements.79Fortna, Peace Time. The United States does not necessarily have a stake in the specific terms that Ukraine and Russia agree to, but it does have an interest in the two sides reaching a mutually agreeable set of commitments able to sustain the peace over the long term.

Although it may seem unlikely, Russia and Ukraine have some overlapping preferences when it comes to commitments each would like the other to make. For example, they might each commit to ban foreign military forces from basing, permanently or rotationally, on their soil, along with restricting or prohibiting military exercises that involve foreign forces. This would prevent the deployment of U.S. military forces into Ukraine as well as NATO exercises and training in Ukraine, but this would not be a loss. There is little evidence that NATO-provided training in Ukraine in the period between 2014 and 2022 did much to improve Ukraine’s combat proficiency at scale and even training conducted in Europe has been of questionable value.80Alexandra Chinchilla, “Lessons from Ukraine for Security Force Assistance,” Lawfare, September 10, 2023, https://www.lawfaremedia.org/article/lessons-from-ukraine-for-security-force-assistance; “In Ukraine, a War of Incremental Gains as Counteroffensive Stalls,” Washington Post, December 4, 2023, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2023/12/04/ukraine-counteroffensive-stalled-russia-war-defenses/; Jamie Dettmer, “Ukraine’s Forces Say NATO Trained Them for Wrong Fight,” Politico, September 22, 2023, https://www.politico.eu/article/ukraine-war-army-nato-trained-them-wrong-fight/. Moreover, Ukraine would benefit from a Russian commitment to limit foreign forces inside Russia, as this would prevent countries like North Korea from sending reinforcements in the future.

The two sides could also agree to geographic restrictions on the locations of military forces and weapons, for example, limiting the locations of long-range strike missiles, permanent deployments of military forces, military bases, and other weaponry to some distance from their shared borders. Such restrictions would be in addition to the DMZ and would be most relevant along the rest of their joint border and perhaps the Ukrainian border with Belarus.

Any concessions made in this area should be mutual—what Ukraine commits to Russia should also commit to—so that both sides are seen to make sacrifices. In the end, Ukraine’s security would be protected not damaged. Though there might be limits on where it can base forces and weapons, Russia would have similar limits, across the entirety of their shared border. Kyiv would thus have an additional buffer and more warning before any Russian aggression reached its borders. Other commitments like non-use of force pledges and confidence building measures like dispute resolution mechanisms and diplomatic channels would be useful, though these would not be sufficient on their own to hold the peace.

Both sides may be hesitant to agree to these concessions, but the United States should insist on them and identify a multilateral and neutral group of countries that can monitor compliance and alert interested parties to violations. The United States should be willing to use its leverage again to push the two sides to an agreement, offering additional security or investment aid to Ukraine or sanctions relief to Russia if they can reach an agreement.

There are other non-security issues that the two sides will need to sort out but where the United States has limited stakes. Many are humanitarian, for instance prisoner of war transfers, the status of Ukrainians living in Russian occupied territories, and Ukrainian guarantees for the rights of Russian minorities in Ukraine. Some of these matters have been less contentious and should be more easily addressed. There is also the issue of accountability, where each side wants reparations or consequences for the other. The United States should stay out of war crimes issues and push both sides away from reparations, as punitive measures could scuttle any deal.

Leaving the United States stronger and more secure

The peace plan outlined here would advance U.S. interests in many ways. It would end the fighting in Ukraine, establish a ceasefire and monitoring regime designed to prevent renewed conflict, put Ukraine on a path to long-term self-defense, stabilize U.S. and NATO relations with Russia, push forward U.S. efforts to reduce its responsibility for Europe’s security, and put guardrails on the problematic Ukraine-Russia relationship. This is an ambitious agenda, and these outcomes might be reached in pieces rather than all at once, but it is also far more realistic than any proposal put forward by Ukraine or Russia, and it is a sustainable one that offers all sides—Ukraine, Russia, Europe, and the United States—some support for their security goals while safeguarding U.S. interests.

Getting the parties to the table for the first round of talks may still be a challenge. Although both sides have paid high costs, neither is satisfied with the status of war or ready to surrender. Ukraine will likely be more easily compelled to begin talks given its dependence on U.S. security assistance, and Washington should not be afraid to use this as a stick. Offering more military aid to Ukraine for its willingness to negotiate, as suggested by some in Washington, is not really feasible given low defense stocks, but promising future security and economic aid might be.81Jason Breslow and Tom Bowman, “Trump Names Rep. Mike Waltz as National Security Adviser,” NPR, November 12, 2024, https://www.npr.org/2024/11/11/nx-s1-5187098/trump-national-security-adviser-mike-waltz; Keith Kellogg and Fred Fleitz, “America First, Russia, & Ukraine,” America First Policy Institute, April 11, 2024, https://americafirstpolicy.com/issues/america-first-russia-ukraine.

For Russia, the promise of potential changes to the U.S. role in Europe that would achieve some of its political objectives may be enough to bring it to the table, though threats of more sanctions are unlikely to work. In a pinch, holding out Russia’s access in the future to some of the $300 billion in frozen assets might be enticing to Putin. Offering an early Trump-Putin meeting if Russia agrees to a ceasefire and diplomacy might also appeal to Putin’s need for validation.

Achieving a settlement will, however, require focus and patience. There could be dozens of rounds of talks and there will likely be setbacks along the way. The Trump administration should be prepared for this and should not let frustration lead to satisficing that sacrifices U.S. positions, either by taking on commitments that are not in U.S. interests or conceding too much to Russia and risking renewed aggression later on.

U.S. negotiators will have to remember to keep U.S. interests first, pushing back not only on Russia but on European and Ukrainian pressure when necessary. A peace deal that leaves the United States with more security burdens and at a higher risk of major war than it is today would be no achievement. Winning the peace will require a deal that does not just end the conflict but leaves the United States stronger and more secure as it looks to the future.

Endnotes

- 1Edward Helmore, “Trump Says He Has Spoken with Putin about Ending Ukraine War,” Guardian, February 9, 2025, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2025/feb/09/trump-putin-ukraine-war.

- 2“What is Zelenskyy’s 10-Point Peace Plan?” Official Website of Ukraine, September 17, 2024, https://war.ukraine.ua/faq/zelenskyys-10-point-peace-plan/; Max Boot, “Zelenskyy’s ‘Victory Plan’ for Ukraine Makes Sense. It Has Little Chance of Being Implemented,” Council on Foreign Relations, October 21, 2024, https://www.cfr.org/expert-brief/zelenskyys-victory-plan-ukraine-makes-sense-it-has-little-chance-being-implemented.