September 10, 2020

Scenarios for post-U.S. Afghanistan

Key points

- U.S. military withdrawal may not further destabilize Afghanistan, as is sometimes assumed. The balance of power among Afghan forces and the interests of outside powers mean Afghanistan’s present circumstances may roughly endure.

- No matter what Afghanistan’s eventual fate, the U.S. will remain fundamentally safe following military withdrawal. Local forces can contain any terrorism originating there, and the U.S. global capability to remotely monitor and strike terrorists will remain potent.

- Powers nearby Afghanistan, with the partial exception of Pakistan, share a strong interest in providing stability. Ending the U.S. military presence in Afghanistan—in addition to conserving resources and eliminating risks to U.S. personnel—will shift that burden onto those nations.

- Full military withdrawal serves U.S. interests, reducing our burdens and therefore pressuring nearby powers—some of them U.S. rivals—to invest more in Afghanistan’s stability. Trouble there is a greater threat to them than to the United States.

Exiting Afghanistan will shift burdens to other nations, including some U.S. rivals

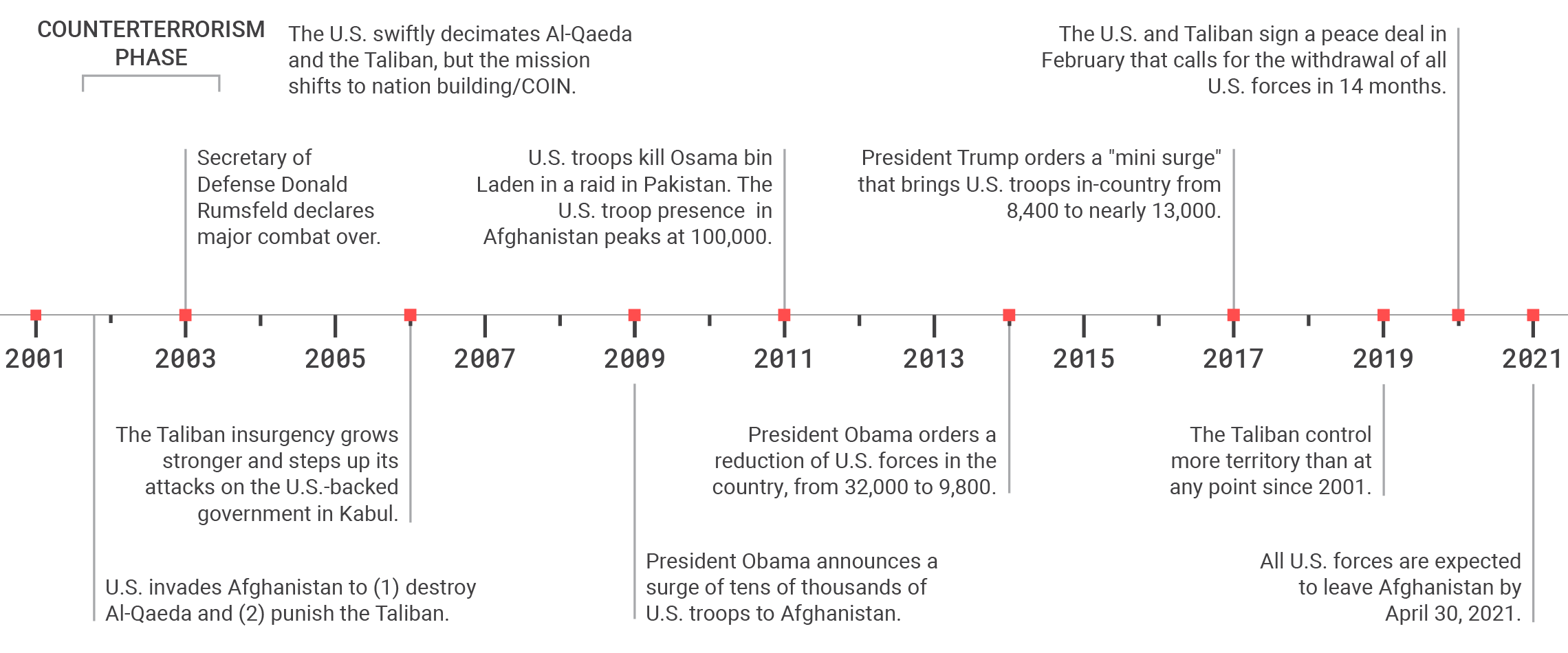

On February 29, 2020, U.S. and Taliban negotiators announced an agreement that would withdraw all U.S. forces from Afghanistan within 14 months in exchange for the Taliban renouncing Al-Qaeda and preventing any of its members from launching, or otherwise cooperating to launch, anti-U.S. terror attacks from Afghan soil. In a nod to reality on the ground, this deal does not address Taliban relations with the internationally recognized government in Kabul beyond requiring a commencement of talks between the sides.1Jennifer Hansler, “U.S. and Taliban Sign Historic Agreement,” CNN, February 2, 2020, https://www.cnn.com/2020/02/29/politics/us-taliban-deal-signing/index.html. More than six months later, these talks have yet to commence, but the U.S. is edging closer to ending its participation in Afghanistan’s civil war.

The White House recently announced the number of U.S. troops in Afghanistan will soon be reduced to between 4,000 and 5,000, from a peak of 100,000 in 2011.2Thomas Gibbons-Neff, “More U.S. Troops Will Leave Afghanistan Before the Election, Trump Says,” New York Times, August 4, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/04/world/asia/us-troops-afghanistan.html. Given the costs of staying and the failure of the occupation to achieve its ends, this drawdown should be quickly completed—no later than the April 2021 deadline—without waiting for a negotiated peace settlement in Afghanistan, which may never come.3Benjamin H. Friedman, “Exiting Afghanistan: Ending America’s Longest War,” Defense Priorities, August 2019, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/exiting-afghanistan.

Yet a number of obstacles could disrupt the plan and prevent the full U.S. withdrawal. One is the tendency of U.S. analysts to conflate nation building with counterterrorism and to argue against withdrawal on the grounds that terrorist safe havens will remain.4Daniel L. Davis, “Debunking the Safe Haven Myth,” Defense Priorities, May 2020, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/debunking-the-safe-haven-myth. Another hurdle is that some U.S. leaders might use the failure of the Afghan parties to cut a peace deal as a rationale for keeping U.S. troops as leverage to induce one.5Gil Barndollar, “U.S. Military Withdrawal from Afghanistan, With or Without an Agreement,” Defense Priorities, August 2019, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/us-military-withdrawal-from-afghanistan-with-or-without-an-agreement. A third impediment is the fear that foreign powers will keep chaos roiling Afghanistan without U.S. help, preventing the country from stabilizing. This paper addresses that third worry, arguing that U.S. withdrawal will instead likely encourage nearby powers to do more to limit violent chaos in Afghanistan.6Barry R. Posen, “It’s Time to Make Afghanistan Someone Else’s Problem,” Atlantic, August 18, 2017, https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2017/08/solution-afghanistan-withdrawal-iran-russia-pakistan-trump/537252/.

There are two likely scenarios for Afghanistan after the U.S. withdraws:

- stability through unification of the country under one power or through factionalism under a power-sharing arrangement, or

- instability due to state failure and the collapse of any unified authority.

The first scenario includes several forms of peace—only the scenario of state failure and collapse presents a net decline in stability for Afghanistan and potentially the surrounding region. None of these likely outcomes would directly harm U.S. security, and thus should not deter a full U.S. withdrawal from the country. As the U.S. steps back, regional powers such as Russia and China—which would be more directly harmed by a collapse of order in Afghanistan—would likely intervene diplomatically, and perhaps through military aid, to broker some form of security equilibrium in Afghanistan.

Because the Afghan military depends heavily on U.S. assistance, withdrawal will likely exacerbate Afghanistan’s turmoil. Afghanistan’s future is unpredictable and tragic results are likely in any event (even if the U.S. stays for two more decades). But even the worst-case scenario will have little impact on U.S. security. It is worth remembering U.S. troop withdrawal does not eliminate the U.S. military’s ability to provide aid, gather intelligence, and launch targeted strikes at specific anti-U.S. threats. The U.S. can achieve its counterterrorism objectives under almost any circumstances.

Timeline of U.S. military operations in Afghanistan

Moreover, neighboring countries will, by necessity, do more to mitigate trouble when U.S. forces leave. They have a greater interest than the U.S. in containing disruption created by ongoing strife in Afghanistan, and they will help suppress it if necessary.

There is no regional actor, save perhaps Pakistan, that is content working with a major state failure or an expansionist Taliban movement in Afghanistan. Most powers may be willing to tolerate a range of outcomes, but safe havens for non-state militants are not on that list.

The U.S. presence is suppressing the efforts of local powers to work toward stability in Afghanistan by dividing those who first want the U.S. out of the region from those willing to work with anyone who holds the Taliban at bay. As an added benefit, the U.S. no longer doing the heavy lifting means the burden will be transferred to other countries—including several U.S. rivals.

How Afghans will respond after U.S. military withdrawal

Under no scenario after a U.S. withdrawal is Afghanistan likely to create a new “safe haven” to terrorists.7Davis, “Debunking the Safe Haven Myth.”

With its spy network, regional contacts, ability to trade information with other countries concerned about Islamists militants, improved technical surveillance capability, and the striking power of both special forces and drones, the U.S. retains the ability to disrupt operations by non-state actors in Afghanistan without ground deployments.8John Mueller and Mark G. Stewart, “Public Opinions and Counterterrorism Policy,” Cato Institute, February 20, 2018, https://www.cato.org/publications/white-paper/public-opinion-counterterrorism-policy; Jon R. Lindsay, “Reinventing the Revolution: Technological Visions, Counterinsurgent Criticism, and the Rise of Special Operations,” Journal of Strategic Studies (February 2013): 1–32; Asfandyar Mir, “What Explains Counterterrorism Effectiveness? Evidence from the U.S. Drone War in Pakistan,” International Security (Fall 2018): 45–83.

A second reason is that the Taliban have strong reason to police against international terrorists. True, the Taliban is decentralized, so enforcement of any deal’s anti-terrorism provisions may prove uneven at best, with rogue commanders not necessarily following central direction.9John R. Allen, “The U.S.-Taliban Peace Deal, a Road to Nowhere,” Brookings Institution, March 5, 2020, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2020/03/05/the-us-taliban-peace-deal-a-road-to-nowhere; Frud Bezham, “Iranian Links: New Taliban Splinter Group Emerges That Opposes U.S. Peace Deal,” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, June 9, 2020, https://www.rferl.org/a/afghanistan-taliban-splinter-group-peace-deal-iranian-links/30661777.html. But the Taliban have a distinct self-interest to avoid provoking a return of U.S. forces after they withdraw. Given the existing hostility between the Taliban and radical elements like ISIS-K, it is unlikely such groups would thrive even if the Taliban were to dominate the country. The mainline Taliban seems capable of enforcing its edicts on recalcitrant elements if sufficiently motivated.

Third, after U.S. departure, whatever one fears of the Taliban, they are unlikely to take over the country entirely. A U.S. withdrawal would weaken the Kabul government, but its collapse is hardly guaranteed. It is certainly possible that the Afghan state will retain partial control over the bulk of the country either in alliance with other non-state actors or as a result of patronage from other regional states. Should this happen, the internationally recognized government will be the primary recipient of foreign aid. With no more U.S. presence to complicate the calculations of other powers, the odds of Kabul finding increased patronage from Beijing, Moscow, or both increase dramatically. Due to geographic proximity alone, these countries would be invested in the fate of a government that could show its continued survival, even if in a reduced territorial capacity.10Craig Nelson and Thomas Grove, “Russia, China Vie for Influence in Central Asia as U.S. Plans Afghan Exit,” Wall Street Journal, June 19, 2019, https://www.wsj.com/articles/russia-china-vie-for-influence-in-central-asia-as-u-s-plans-afghan-exit-11560850203.

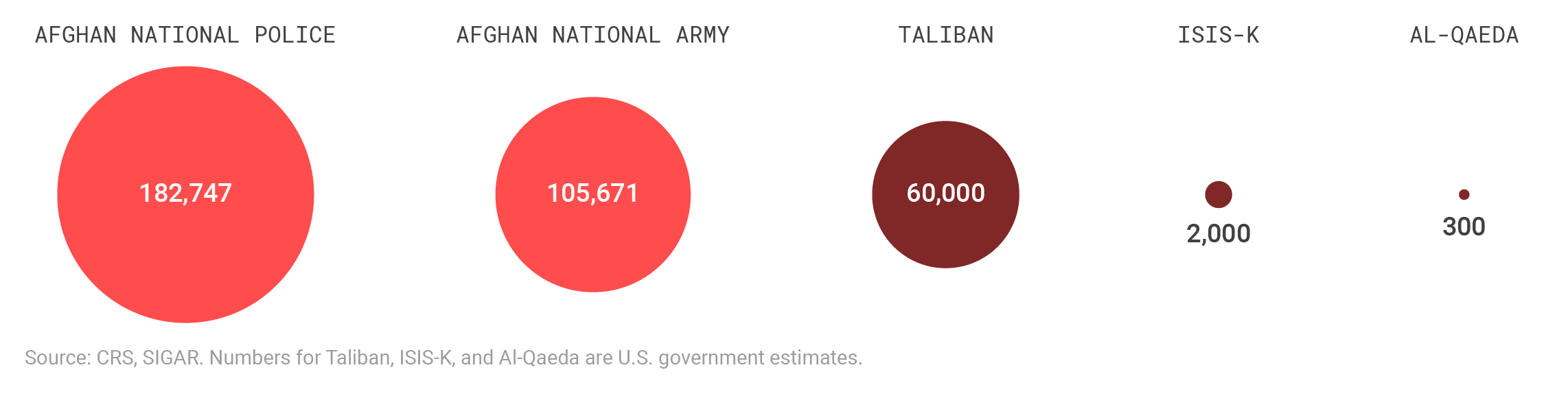

Afghan national security forces compared with insurgent and terrorist forces

The government in Kabul has resources to vie for control after a U.S. withdrawal, including active personnel in its police and army that far outnumber Taliban fighters and terrorist members in ISIS-K and Al-Qaeda.

On the other hand, should Kabul fall, the resulting patchwork of forces—including internal divisions in the Taliban itself—do not make the conquest of the entire country by the Taliban inevitable. The Taliban are as likely to face regional warlords and rebellion as the Kabul government has, especially in non-Pashtun areas. A power vacuum could also lead to a fracturing of the dominant coalitions and the collapse of alliances only kept together by the existence of U.S. forces, a common enemy.

A full takeover by the Taliban, while unifying the country, would likely prompt outside containment. Neighboring powers would likely either support armed rivals to the Taliban to extract concessions or use pan-regional diplomacy to curtail Islamist movements from spreading further in Central Asia.11Yun Sun, “China’s Strategic Assessment of Afghanistan,” War on the Rocks, April 8, 2020, https://warontherocks.com/2020/04/chinas-strategic-assessment-of-afghanistan.

Even the worst-case scenario—a complete state collapse—would not necessarily prompt a rise in non-state extremists’ ability to operate in Afghanistan. Anarchic environments often spur armed groups to focus more on survival than on plotting sophisticated acts of terrorism, and subnational authorities in Afghanistan are unlikely to find global jihad—or being on the receiving end of American, Russian, or Chinese responses to it—a welcome addition to their autonomous fiefdoms.12Jennifer Keister, “The Illusion of Chaos: Why Ungoverned Spaces Aren’t Ungoverned, and Why That Matters,” Cato Institute, December 9, 2014, https://www.cato.org/publications/policy-analysis/illusion-chaos-why-ungoverned-spaces-arent-ungoverned-why-matters.

Should the Taliban become the dominant actor among many in the country, their control will likely be regionally limited and locally challenged, demanding an internal focus and leaving few resources for broader aims. Any independent groups seeking to set up terrorist networks in this environment would lack state sponsorship and thus defense from outside powers.13Anne Stenerson, “Are the Afghan Taliban Involved in International Terrorism?” CTC Sentinel 2, no. 9 (September 2009): 1–5, https://ctc.usma.edu/are-the-afghan-taliban-involved-in-international-terrorism-3.

U.S. departure will change the Taliban’s priorities. As the Taliban transitions from an insurgency to a formal political movement, it would be able to access official revenue streams and outside support to battle its more radical offshoots. Existing Taliban hostility to ISIS’s presence in the country could increase. The two groups have already fought openly, and without the strain of battling the U.S., the far larger Taliban is likely to eradicate the ISIS presence over time.

How outside powers will respond to events inside Afghanistan

Following U.S. withdrawal, Afghanistan’s neighbors are likely to coalesce around similar strategies to deal with the aftermath. Their preferred outcomes are peace through unification or a power-sharing arrangement.

A Taliban amenable to negotiation would also be an outcome that regional powers could adapt to and contain. The least desirable path for the region is the total collapse of centralized authority in the country or a Taliban unwilling to pursue normal relations and returning to its pre-9/11 international stance. As previously noted, this final outcome is unlikely because the Taliban would not want to invite additional intervention by either the U.S. or other great powers.

Scenario 1: Stability through unification or power-sharing

The best feasible outcome for the U.S. is the survival of the Kabul government in more or less its present form. Most of Afghanistan’s neighbors would agree. Diplomacy and business would continue as normal and the country would enjoy some measure of security and international support.

China, which is linked to Afghanistan not only by a short border, but also by its deep suspicion of Islamist radicals, could well find it expedient to support the current government. Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)—which includes expanding infrastructure projects in Afghanistan—as well as ongoing projects in Badakshan Province, give China an economic reason to avoid political disruption. Beijing could well find itself backing and brokering any Kabul-Taliban negotiations, especially following the U.S. departure—leaving would pressure China to take on those burdens.14Sudha Ramachandran, “Is China Bringing Peace to Afghanistan?” Diplomat, June 20, 2018, https://thediplomat.com/2018/06/is-china-bringing-peace-to-afghanistan.

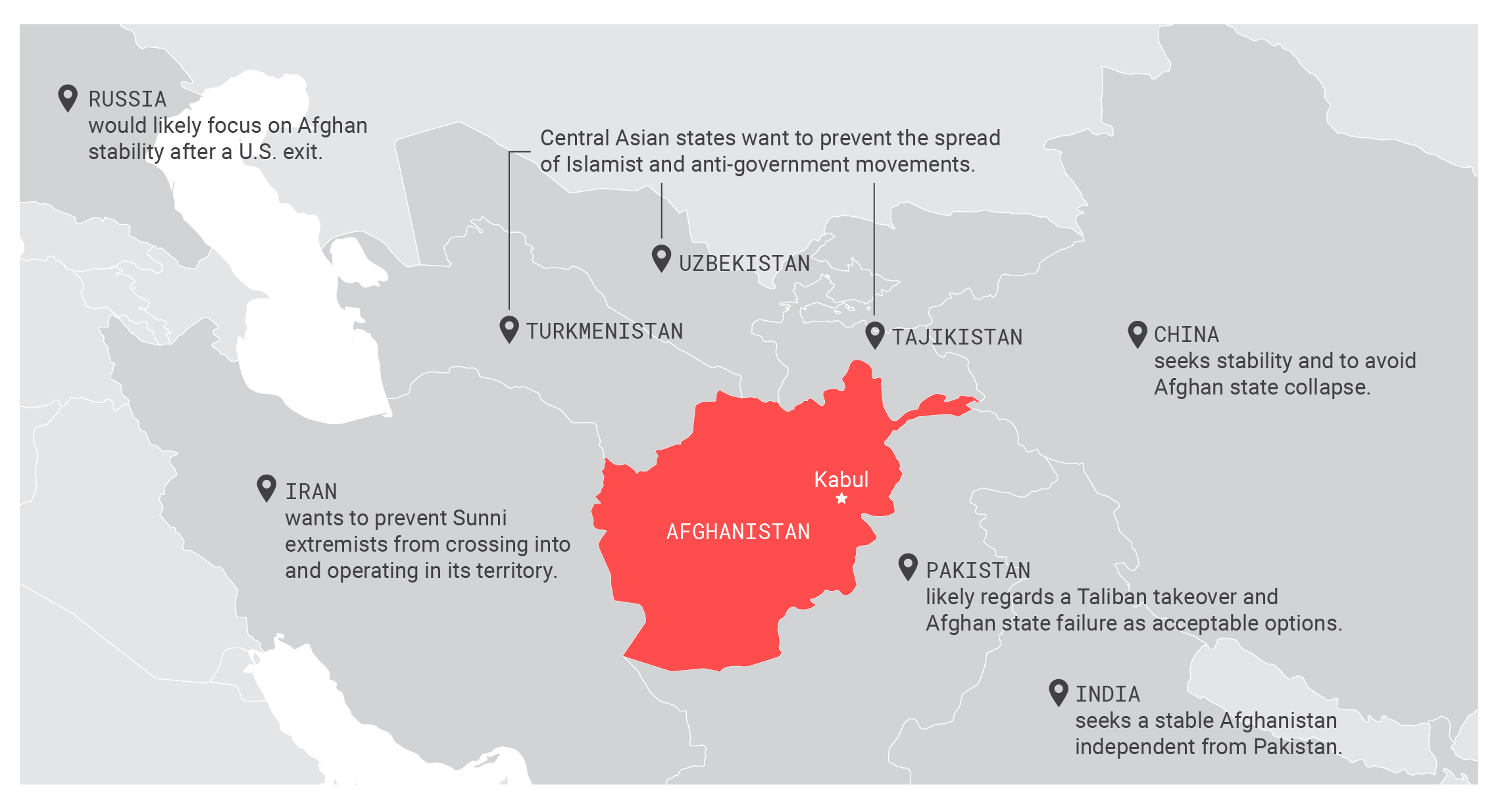

Map of Afghanistan’s neighbors and regional powers

With the possible exception of Pakistan, which may find state failure acceptable, countries near Afghanistan likely will seek to prevent it from degenerating into a more chaotic state that exports trouble.

Only Pakistan, a key supporter of the Taliban, would likely welcome its victory. Should that fail to materialize, however, Islamabad’s past behavior implies it would likely seek to avoid a total collapse of governance in Afghanistan, which would diminish its ability to influence events and create a power vacuum that others might exploit.15Mark Mazzetti, “The Devastating Paradox of Pakistan,” Atlantic, March 2018, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2018/03/the-pakistan-trap/550895/. Furthermore, Pakistan’s dire financial situation means that it is easily influenced by wealthier patrons, like China, which already exercises a large degree of sway over Islamabad and has little interest in facilitating Islamist militancy.16Zia Ur Rehman, “China Pushes Pakistan to Open Trade Routes with Afghanistan,” Nikkei Asian Review, August 24, 2020, https://asia.nikkei.com/Spotlight/Belt-and-Road/China-pushes-Pakistan-to-open-trade-routes-with-Afghanistan.

China might apply pressure on Pakistan to either rein in the Taliban or aid negotiations between the Taliban and Kabul. Should the Taliban take a more hostile approach, Beijing could pressure the Pakistani government, leading it to make its Taliban clients more amenable to Beijing’s priorities.17Shubhangi Pandey, “Understanding China’s Afghanistan Policy: From Calculated Indifference to Strategic Engagement,” Observer Research Foundation, August 6, 2019, https://www.orfonline.org/research/understanding-chinas-afghanistan-policy-from-calculated-indifference-strategic-engagement-54126. Chinese policymakers fear the consequences of an Islamist Afghanistan, which could disrupt order in their restive Xinjiang province.

Additionally, the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia recently managed to extract concessions from Pakistan on Taliban-U.S. talks in exchange for loans. Because these countries want Pakistan on their side as part of a containment strategy against Iran, it is likely they will seek to reorient Pakistani policy away from Afghanistan as a primary focus.18Barnett R. Rubin, “Everyone Wants a Piece of Afghanistan,” Foreign Policy, March 11, 2019, https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/03/11/everyone-wants-a-piece-of-afghanistan-russia-china-un-sco-pakistan-isi-qatar-saudi-uae-taliban-karzai-ghani-khalilzad-iran-india/.

Russia, while seeking to oust the U.S. from a region it considers its backyard, is also alarmed by the spread of Islamist insurgencies in Central Asia, and it would welcome a stable government in Afghanistan.19Lara Seligman, “As U.S. Mulls Withdrawal from Afghanistan, Russia Wants Back In,” Foreign Policy, January 31, 2019, https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/01/31/us-mulls-withdrawal-from-afghanistan-russia-wants-back-in-taliban-peace-talks. Currently, Washington is serving Moscow’s interests by expending its own resources to battle radical insurgents in the region.

The U.S. and Afghan governments have both suggested that Moscow developed indirect ties to the Taliban in order to sow division between that group and ISIS (as well as make the U.S. position more difficult).20Sune Engel Rasmussen, “Russia Accused of Supplying Taliban as Power Shifts Create Strange Bedfellows,” Guardian, October 22, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/oct/22/russia-supplying-taliban-afghanistan; “Afghanistan: Background and U.S. Policy: In Brief,” Congressional Research Service R45122, June 25, 2020, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/R45122.pdf. Even if these suspicions are true, they will cease being relevant upon U.S. departure from Afghanistan, as Russia’s position toward Afghanistan will adapt to the new reality.21Nicholas Trickett, “Making Sense of Russia’s Involvement in Afghanistan,” Diplomat, August 2, 2018, https://thediplomat.com/2018/08/making-sense-of-russias-involvement-in-afghanistan. U.S. withdrawal would likely compel Moscow to play a more constructive role in the country—Afghanistan’s stability is more important to Russia’s long-term interests than it is to the U.S. This also comes with the added benefit of taking Russian resources away from potential Moscow-directed meddling elsewhere in the world.

Should Kabul achieve stable governance, the post-Soviet Central Asian states will be the first to seek more trade with their neighbor.22Humayun Hamidzada and Richard Ponzio, “Central Asia’s Growing Role in Building Peace and Connectivity in Afghanistan,” United States Institute of Peace, August 27, 2019, https://www.usip.org/publications/2019/08/central-asias-growing-role-building-peace-and-regional-connectivity. Uzbekistan, as the most influential of these states, often takes a quite independent line in the region and could be expected to want to play a major diplomatic role in bringing Afghan factions together.23Wilder Alejandro Sanchez, “Central Asia and Afghanistan: Helping Your Neighbor,’ Geopolitical Monitor, August 7, 2018, https://www.geopoliticalmonitor.com/central-asia-and-afghanistan-helping-your-neighbor. Tajikistan and Turkmenistan will utilize as much diplomatic outreach as they can muster to support a peace considering their fear of instability bleeding over the borders and into their own struggles with anti-government groups. A Taliban takeover would be a massive danger worth balancing against in a regional coalition but could also present an opportunity for negotiation.24John C. K. Daly, “Central Asia Nervously Awaits Withdrawal of Foreign Militaries from Afghanistan,” Central Asia-Caucasus Analyst, April 8, 2020, https://www.cacianalyst.org/publications/analytical-articles/item/13612-central-asia-nervously-awaits-withdrawal-of-foreign-militaries-from-afghanistan.html. Uzbekistan has cultivated informal relations with the Taliban just in case this scenario comes to pass.25Umida Hashimova, “What is Uzbekistan’s Role in the Afghan Peace Process?” Diplomat, March 11, 2019, https://thediplomat.com/2019/03/what-is-uzbekistans-role-in-the-afghan-peace-process.

In Afghanistan, the U.S. is fighting Iran’s enemy for them. Iran and the Taliban were foes in the 1990s, then gradually became very reluctant associates against a common enemy as the U.S. occupation dragged on and U.S.-Iran relations worsened.26Ariane M. Tabatabai, “Iran’s Cooperation with the Taliban Could Effect Talks on U.S. Withdrawal from Afghanistan,” RAND Corporation, August 9, 2019, https://www.rand.org/blog/2019/08/irans-cooperation-with-the-taliban-could-affect-talks.html. But the expediency of this relationship would not continue at the same level upon U.S. departure.27Mahan Abedin, “How Iran Found Its Feet in Afghanistan,” Foreign Affairs, October 24, 2019, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/afghanistan/2019-10-24/how-iran-found-its-feet-afghanistan.

Tehran’s goals are to maintain security for its porous eastern border and prevent Sunni extremists from operating in its territory. It would likely work with any non-Taliban government that is divorced from U.S. support. Taliban takeover is Tehran’s worst-case scenario, even though Iranian-Taliban relations have improved in recent years as a partnership of convenience to thwart U.S. goals in Afghanistan.

Iranian interests are more focused on its proxy conflicts in Iraq and Syria, so Tehran’s primary goal is simply a stable border region free of a U.S. presence or militant Sunni Islamists. Therefore, Tehran could either leverage the goodwill it gained with the Taliban to help restrain them, or, should these relationships break down, act as another anti-Taliban containment force via logistical support of proxies in the region, as it has done in Iraq and Yemen.

New Delhi has become Afghanistan’s most consistent supporter, though to limited effect.28Harsh V. Pant and Avinash Paliwal, “India’s Afghan Dilemma Is Tougher Than Ever,” Foreign Policy, February 19, 2019, https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/02/19/indias-afghan-dilemma-is-tougher-than-ever. India has committed $3 billion of developmental assistance to Kabul over the years to promote stability, but its ability to mold events on the ground is limited due to a lack of ability to project hard power.29Dipanjan Roy Choudhry, “Miffed Government Lists $3 Billion Projects as Donald Trump Mocks India’s,” Economic Times, January 4, 2019, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/miffed-govt-lists-3-billion-projects-as-donald-trump-mocks-indias-afghanistan-aid/articleshow/67375954.cms?from=mdr; “India’s Afghanistan Policy Should Rapidly Adapt to the Evolving Realities,” Economic Times, January 4, 2019, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/view-indias-afghanistan-policy-should-rapidly-adapt-to-the-evolving-realities/articleshow/70951897.cms. A stronger, more stable Afghanistan under the present Kabul government or a coalition arrangement is the best outcome for India. A relative peace holding between different autonomous factions is also acceptable to India, as it diminishes Pakistan’s influence and guarantees India could still invest and play some role in Afghanistan’s future. A Taliban takeover, on the other hand, is undesirable to New Delhi. But it still presents potential opportunities should the new government seek to distance itself from Pakistan.

In the best-case scenario, a U.S. withdrawal would spur regional powers to engage in constructive diplomatic engagement with whatever government is dominant in Afghanistan. China, wanting to achieve the most favorable conditions for BRI, would facilitate the diplomatic normalization of any dominant government in Afghanistan. Russia most likely would be far more reticent but would want to follow a course that maximizes its influence with its smaller Central Asian partners.

No matter which faction comes out on top, however, a dominant domestic power in the country of any type, even the Taliban, is an outcome that could be tolerated by the U.S. Achieving minimal counterterrorism goals and letting neighbors do more will allow the U.S. to leave and focus on more rewarding endeavors.

Scenario 2: State failure and collapse

In Afghanistan, Pakistan is a possible wrench in a sustainable peace under either one controlling power or a stable factionalism. Pakistani intelligence’s longstanding links with the Taliban are coupled with a fear of any kind of strong state on their northern border which is not ruled by the Taliban. Islamabad’s first concern is that such a state would correctly regard Pakistan as its primary foreign security threat and reach out to India for warmer relations.30William Dalrymple, “A Deadly Triangle: Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India,” Brookings Institution, June 25, 2013, http://csweb.brookings.edu/content/research/essays/2013/deadly-triangle-afghanistan-pakistan-india-c.html#. Fearing encirclement and an increase in Indian influence near its borders, Pakistan likely regards both Taliban takeover and utter state failure in Afghanistan as acceptable options, unlike other nearby powers, even if state collapse could harm Islamabad.31Vanda Felbab-Brown, “Pakistan’s Relations with Afghanistan and its Implication of Regional Politics,” National Bureau of Asian Research, Brookings Institution, May 14, 2015, https://www.brookings.edu/research/pakistans-relations-with-afghanistan-and-implications-for-regional-politics/. This is, however, an outlier position in the international community.

Overwhelmingly, the consensus in the region is that state collapse is both a possibility and a negative outcome. This implies that neighboring states would take action to either contain chaos in Afghanistan through regional security measures, and erect hard borders around the country, back more moderate factions to battle the radicals, and potentially directly employ forces to counter non-state actors through joint actions.

Afghanistan’s neighbors would have a slew of options for dealing with non-state and rogue actors that are not presently available with the current U.S. presence. Russian special forces teams operating out of their bases in Tajikistan would be able to gather intelligence and launch targeted missions against radical groups deemed threatening. Chinese and perhaps even Indian financial contacts could be set up with specific warlords and autonomous regions in order to pursue localized development projects and combat opium production.

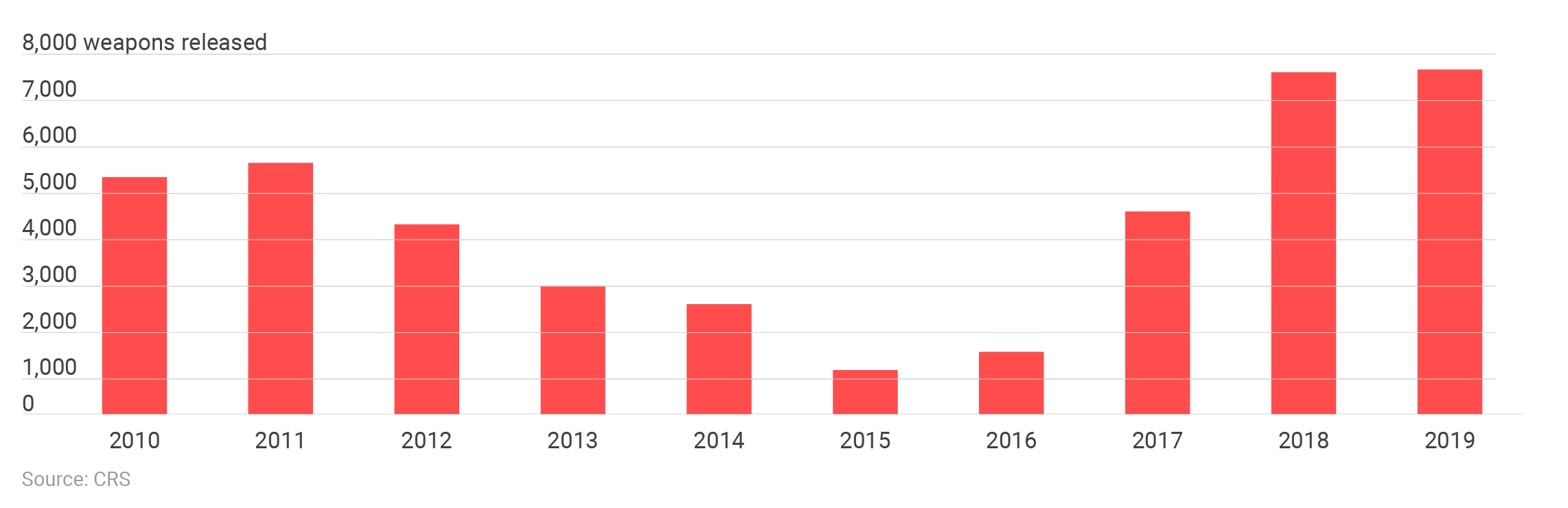

Number of weapons released by U.S. aircraft in Afghanistan

U.S. air operations in Afghanistan have increased in recent years, even as the number of U.S. troops has fallen, indicating that the ability of the U.S. to strike is not a direct function of the number of personnel garrisoned in the country.

All of this could increase the odds of regional foreign investment in Afghanistan on a time scale that the distant and overextended U.S. never could. While foreign spending is no more likely to ameliorate Afghanistan’s political strife than U.S. spending, it can at least help prop up the national or local authorities. Should this not work out, a worst-case scenario where the neighboring Central Asian countries could coordinate a common containment policy in partnership with Russia and China is feasible. No power in Afghanistan would be strong enough to meaningfully object.

While this worst-case scenario brings together many U.S. rivals, it does so in a way that minimizes the potential negative fallout of U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan.

Yet even if regional powers and their proxies in Afghanistan compete rather than cooperate, that competition would keep them fixated on nearby goals, not the distant target of the U.S. For instance, Iranian backing of a potential warlord running afoul of a Russian backed faction simply means more difficulty for Tehran and Moscow, more regional problems for Afghan actors, and no negative security result for the U.S.

Conclusion

The end of direct U.S. involvement in Afghanistan does not guarantee a long-term decline in regional stability. It does, however, guarantee a shift in U.S. attention away from unwinnable conflicts and increased efforts by local powers to stabilize Afghanistan.

Most regional powers must in some way deal with the aftermath of a U.S. withdrawal, whether through diplomacy, military containment, or some combination. The U.S. presence in Afghanistan distorts regional dynamics between Afghanistan and its neighbors. Though short-term instability will likely rise after withdrawal, the interests of neighboring states, some of them U.S. strategic competitors, ensure they will work to restore some sort of balance to Afghanistan’s affairs. The region may end up looking similar to its geopolitical equilibrium prior to the U.S. invasion—but with regional states having increased interests to deal with terrorist organizations. This also means that the nearby countries are not likely to object to the U.S. retaining some ability to strike at non-state actors through indirect methods and proxies in the region should the need arise. Or—to keep the U.S. out—other countries may volunteer to do these operations themselves.

Almost all of Afghanistan’s neighbors have an interest in preventing regional chaos. Only Pakistan seems a likely dissenter. This puts Islamabad in an unenviable position vis-à-vis its relationships with the Central Asian republics, Russia, and, above all its unofficial patron, China. Though Pakistan’s ability to influence the situation on the ground remains unrivaled due to its geographic location and 1,659-mile shared border with Afghanistan, the harder it pushes to help the Taliban, the more pushback it will receive in turn from almost every other significant nation concerned with Afghanistan’s future. This is a dynamic aided by the removal of all U.S. forces in the Afghanistan.

Outside of Islamabad, the consensus is a peace that retains a non-Taliban government is the best option and the one most amenable to trade, diplomacy, and working on cross-border extremism problems endemic to the region. However, nearly all powers have retained a large degree of flexibility regarding the possibility of a Taliban takeover.

The instinct of these societies to balance threats to their sovereignty and support of China and Russia for the smaller states of the region could modify Taliban behavior. A Taliban that restrains itself and respects the sovereignty of its neighbors could find that surrounding countries are willing to do business just as they are with the current government in Kabul.

Whatever differences divide Russia, China, the Central Asian republics, and Iran, all share one vital interest: countering a hotbed of expansionist extremism on their borders. Knowing this, the Taliban would be wise to work to avoid being the target of yet another international coalition. This is one reason why even a full Taliban victory need not meaningfully harm U.S. security.

Withdrawal yields substantial benefits for the U.S. A localized future for Afghanistan should be welcomed by U.S. strategists and decision makers, as it removes U.S. reliance on cordial relations with increasingly dysfunctional Pakistan and frees up U.S. policymakers to pursue a more flexible stance towards Southern Asia and India in particular. No longer burdened with sustaining a permanent force in landlocked and remote Afghanistan, the U.S. could pursue more important, and fruitful, goals elsewhere.

Endnotes

- 1Jennifer Hansler, “U.S. and Taliban Sign Historic Agreement,” CNN, February 2, 2020, https://www.cnn.com/2020/02/29/politics/us-taliban-deal-signing/index.html.

- 2Thomas Gibbons-Neff, “More U.S. Troops Will Leave Afghanistan Before the Election, Trump Says,” New York Times, August 4, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/04/world/asia/us-troops-afghanistan.html.

- 3Benjamin H. Friedman, “Exiting Afghanistan: Ending America’s Longest War,” Defense Priorities, August 2019, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/exiting-afghanistan.

- 4Daniel L. Davis, “Debunking the Safe Haven Myth,” Defense Priorities, May 2020, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/debunking-the-safe-haven-myth.

- 5Gil Barndollar, “U.S. Military Withdrawal from Afghanistan, With or Without an Agreement,” Defense Priorities, August 2019, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/us-military-withdrawal-from-afghanistan-with-or-without-an-agreement.

- 6Barry R. Posen, “It’s Time to Make Afghanistan Someone Else’s Problem,” Atlantic, August 18, 2017, https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2017/08/solution-afghanistan-withdrawal-iran-russia-pakistan-trump/537252/.

- 7Davis, “Debunking the Safe Haven Myth.”

- 8John Mueller and Mark G. Stewart, “Public Opinions and Counterterrorism Policy,” Cato Institute, February 20, 2018, https://www.cato.org/publications/white-paper/public-opinion-counterterrorism-policy; Jon R. Lindsay, “Reinventing the Revolution: Technological Visions, Counterinsurgent Criticism, and the Rise of Special Operations,” Journal of Strategic Studies (February 2013): 1–32; Asfandyar Mir, “What Explains Counterterrorism Effectiveness? Evidence from the U.S. Drone War in Pakistan,” International Security (Fall 2018): 45–83.

- 9John R. Allen, “The U.S.-Taliban Peace Deal, a Road to Nowhere,” Brookings Institution, March 5, 2020, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2020/03/05/the-us-taliban-peace-deal-a-road-to-nowhere; Frud Bezham, “Iranian Links: New Taliban Splinter Group Emerges That Opposes U.S. Peace Deal,” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, June 9, 2020, https://www.rferl.org/a/afghanistan-taliban-splinter-group-peace-deal-iranian-links/30661777.html.

- 10Craig Nelson and Thomas Grove, “Russia, China Vie for Influence in Central Asia as U.S. Plans Afghan Exit,” Wall Street Journal, June 19, 2019, https://www.wsj.com/articles/russia-china-vie-for-influence-in-central-asia-as-u-s-plans-afghan-exit-11560850203.

- 11Yun Sun, “China’s Strategic Assessment of Afghanistan,” War on the Rocks, April 8, 2020, https://warontherocks.com/2020/04/chinas-strategic-assessment-of-afghanistan.

- 12Jennifer Keister, “The Illusion of Chaos: Why Ungoverned Spaces Aren’t Ungoverned, and Why That Matters,” Cato Institute, December 9, 2014, https://www.cato.org/publications/policy-analysis/illusion-chaos-why-ungoverned-spaces-arent-ungoverned-why-matters.

- 13Anne Stenerson, “Are the Afghan Taliban Involved in International Terrorism?” CTC Sentinel 2, no. 9 (September 2009): 1–5, https://ctc.usma.edu/are-the-afghan-taliban-involved-in-international-terrorism-3.

- 14Sudha Ramachandran, “Is China Bringing Peace to Afghanistan?” Diplomat, June 20, 2018, https://thediplomat.com/2018/06/is-china-bringing-peace-to-afghanistan.

- 15Mark Mazzetti, “The Devastating Paradox of Pakistan,” Atlantic, March 2018, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2018/03/the-pakistan-trap/550895/.

- 16Zia Ur Rehman, “China Pushes Pakistan to Open Trade Routes with Afghanistan,” Nikkei Asian Review, August 24, 2020, https://asia.nikkei.com/Spotlight/Belt-and-Road/China-pushes-Pakistan-to-open-trade-routes-with-Afghanistan.

- 17Shubhangi Pandey, “Understanding China’s Afghanistan Policy: From Calculated Indifference to Strategic Engagement,” Observer Research Foundation, August 6, 2019, https://www.orfonline.org/research/understanding-chinas-afghanistan-policy-from-calculated-indifference-strategic-engagement-54126.

- 18Barnett R. Rubin, “Everyone Wants a Piece of Afghanistan,” Foreign Policy, March 11, 2019, https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/03/11/everyone-wants-a-piece-of-afghanistan-russia-china-un-sco-pakistan-isi-qatar-saudi-uae-taliban-karzai-ghani-khalilzad-iran-india/.

- 19Lara Seligman, “As U.S. Mulls Withdrawal from Afghanistan, Russia Wants Back In,” Foreign Policy, January 31, 2019, https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/01/31/us-mulls-withdrawal-from-afghanistan-russia-wants-back-in-taliban-peace-talks.

- 20Sune Engel Rasmussen, “Russia Accused of Supplying Taliban as Power Shifts Create Strange Bedfellows,” Guardian, October 22, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/oct/22/russia-supplying-taliban-afghanistan; “Afghanistan: Background and U.S. Policy: In Brief,” Congressional Research Service R45122, June 25, 2020, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/R45122.pdf.

- 21Nicholas Trickett, “Making Sense of Russia’s Involvement in Afghanistan,” Diplomat, August 2, 2018, https://thediplomat.com/2018/08/making-sense-of-russias-involvement-in-afghanistan.

- 22Humayun Hamidzada and Richard Ponzio, “Central Asia’s Growing Role in Building Peace and Connectivity in Afghanistan,” United States Institute of Peace, August 27, 2019, https://www.usip.org/publications/2019/08/central-asias-growing-role-building-peace-and-regional-connectivity.

- 23Wilder Alejandro Sanchez, “Central Asia and Afghanistan: Helping Your Neighbor,’ Geopolitical Monitor, August 7, 2018, https://www.geopoliticalmonitor.com/central-asia-and-afghanistan-helping-your-neighbor.

- 24John C. K. Daly, “Central Asia Nervously Awaits Withdrawal of Foreign Militaries from Afghanistan,” Central Asia-Caucasus Analyst, April 8, 2020, https://www.cacianalyst.org/publications/analytical-articles/item/13612-central-asia-nervously-awaits-withdrawal-of-foreign-militaries-from-afghanistan.html.

- 25Umida Hashimova, “What is Uzbekistan’s Role in the Afghan Peace Process?” Diplomat, March 11, 2019, https://thediplomat.com/2019/03/what-is-uzbekistans-role-in-the-afghan-peace-process.

- 26Ariane M. Tabatabai, “Iran’s Cooperation with the Taliban Could Effect Talks on U.S. Withdrawal from Afghanistan,” RAND Corporation, August 9, 2019, https://www.rand.org/blog/2019/08/irans-cooperation-with-the-taliban-could-affect-talks.html.

- 27Mahan Abedin, “How Iran Found Its Feet in Afghanistan,” Foreign Affairs, October 24, 2019, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/afghanistan/2019-10-24/how-iran-found-its-feet-afghanistan.

- 28Harsh V. Pant and Avinash Paliwal, “India’s Afghan Dilemma Is Tougher Than Ever,” Foreign Policy, February 19, 2019, https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/02/19/indias-afghan-dilemma-is-tougher-than-ever.

- 29Dipanjan Roy Choudhry, “Miffed Government Lists $3 Billion Projects as Donald Trump Mocks India’s,” Economic Times, January 4, 2019, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/miffed-govt-lists-3-billion-projects-as-donald-trump-mocks-indias-afghanistan-aid/articleshow/67375954.cms?from=mdr; “India’s Afghanistan Policy Should Rapidly Adapt to the Evolving Realities,” Economic Times, January 4, 2019, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/view-indias-afghanistan-policy-should-rapidly-adapt-to-the-evolving-realities/articleshow/70951897.cms.

- 30William Dalrymple, “A Deadly Triangle: Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India,” Brookings Institution, June 25, 2013, http://csweb.brookings.edu/content/research/essays/2013/deadly-triangle-afghanistan-pakistan-india-c.html#.

- 31Vanda Felbab-Brown, “Pakistan’s Relations with Afghanistan and its Implication of Regional Politics,” National Bureau of Asian Research, Brookings Institution, May 14, 2015, https://www.brookings.edu/research/pakistans-relations-with-afghanistan-and-implications-for-regional-politics/.