November 15, 2021

The futility of U.S. military aid and NATO aspirations for Ukraine

Key points

- Since the 2014 Russian annexation of Crimea, the U.S. has provided $2.5 billion in military aid to Ukraine. Continued security assistance prolongs the conflict and heightens U.S.-Russia tensions.

- Russia shares a 1,200-mile border with Ukraine and views the prospect of Kyiv joining NATO and basing U.S. and allied forces there as a threat. Russia will absorb significant costs—monetary and human—to prevent this outcome.

- A resolution in Ukraine that does not account for Russia’s concerns is unrealistic; therefore, U.S. and European leaders should account for them, starting with ruling out Ukrainian accession to NATO.

- Because of the risk of escalation, potentially to nuclear war, the U.S. should seek détente with Russia and support the establishment of a neutral, non-aligned Ukraine that serves as a buffer state between Russia and the West.

Repeating the same mistakes in Ukraine

President Biden met with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky at the White House in September 2021 and reiterated the U.S. commitment to Ukraine’s territorial sovereignty. The meeting suggests the Biden administration intends to continue the failed policy of his two predecessors: providing piecemeal security assistance to Ukraine and supporting its eventual accession to NATO.

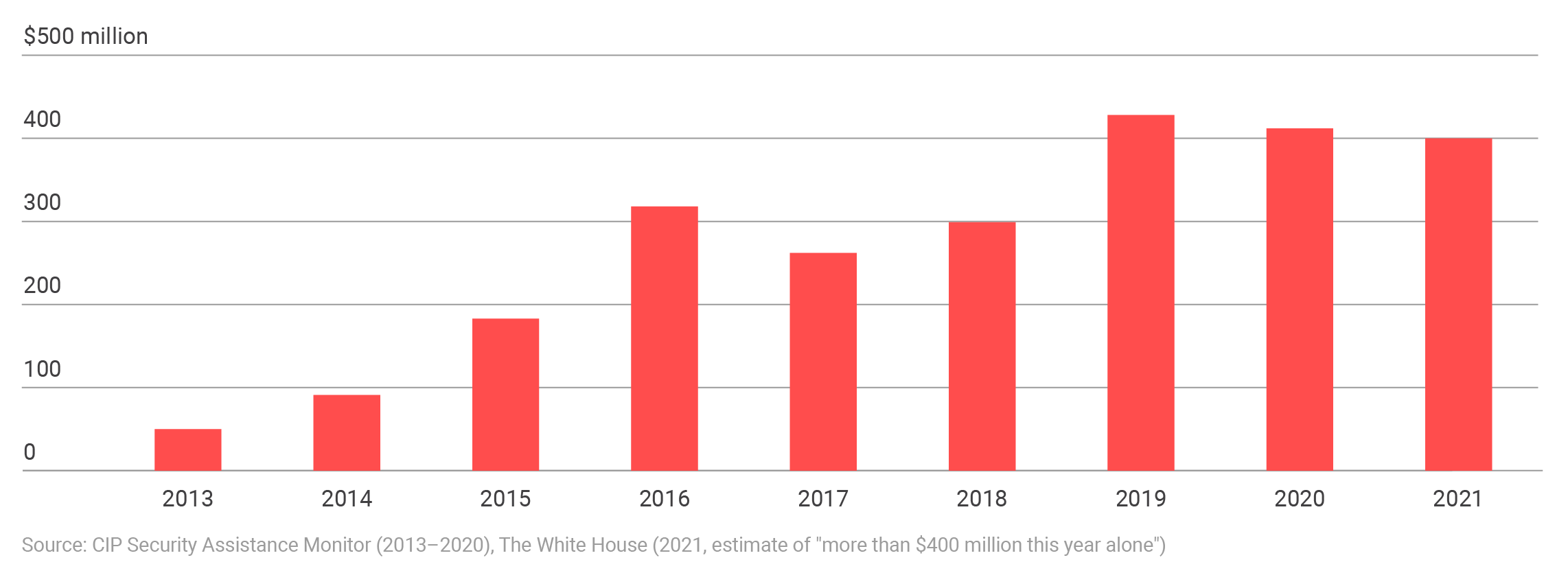

Annual U.S. military aid to Ukraine

The U.S. has provided $2.5 billion in military support to Ukraine since 2014, including more than $400 million in 2021 alone.

U.S. military aid to Ukraine

Ahead of the meeting, President Biden presented a $60 million military aid package to Ukraine, which included Javelin anti-tank missiles, small arms, and ammunition.1“Joint Statement on the U.S.-Ukraine Strategic Partnership,” White House, September 1, 2021, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/09/01/joint-statement-on-the-u-s-ukraine-strategic-partnership. Since hostilities broke out between Ukraine and Russia in 2014, the United States has provided $2.5 billion in security aid to Kyiv, with more than $400 million in the last year alone.2“Joint Statement on the U.S.-Ukraine Strategic Partnership,” White House. U.S. security assistance has come in the form of training, equipment, and weaponry, including tactical unmanned aerial vehicles, night vision devices, sniper rifles, small arms, Javelin anti-tank missiles, high-mobility multipurpose wheeled vehicles, and Mark VI patrol boats. The United States has also provided secure communications, satellite imagery and analysis support, counter-battery radars, and equipment to support military medical treatment and combat evacuation procedures.3“U.S. Security Cooperation with Ukraine,” U.S. Department of State, July 2, 2021, https://www.state.gov/u-s-security-cooperation-with-ukraine. While these weapon systems and equipment increased the warfighting capabilities of Ukraine’s security forces, they failed to meaningfully alter the balance of power between Ukraine and the Russian-backed separatists or bring an end to hostilities. They also failed to stop Russian interference in Ukraine, ranging from direct military aid to influence operations and cyber-attacks.

Despite these continued military transfers from the United States, the conflict continues into its seventh year because the underlying causes of the war have not been sufficiently addressed—particularly Russia’s concern Ukraine will become a western bulwark by allowing U.S. and NATO forces to station there.

Holding out prospects for Ukrainian membership in NATO

The Biden administration continues to rhetorically support Ukraine’s aspirations to join NATO. A joint statement released after the White House meeting in September declared “the United States supports Ukraine’s right to decide its own future foreign policy course free from outside interference, including with respect to Ukraine’s aspirations to join NATO.”4“U.S. Security Cooperation with Ukraine,” U.S. Department of State. Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin reinforced this message during a visit to Kyiv in October.5Matthias Williams and Pavel Polityuk, “Russia Is Obstacle to Peace in East Ukraine—U.S. Defence Secretary,” Reuters, October 19, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/russia-cannot-block-ukraines-nato-aspirations-us-secretary-defence-says-2021-10-19/. Yet even as the administration voiced its support, it has, wisely, not formally extended membership. President Zelensky previously discussed his annoyance at the reluctance of western leaders to admit Ukraine into NATO, and the lack of a firm commitment by Biden likely exacerbates Zelensky’s frustrations.6Isabelle Khurshudyan, “Ahead of White House Meeting, Ukraine’s Zelensky Expresses Frustration with Western Allies,” Washington Post, August 19, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/europe/ukraine-zelensky-interview-russia/2021/08/19/93b475e6-fabe-11eb-911c-524bc8b68f17_story.html.

The reasons for the administration’s apparent hesitancy to extend outright NATO membership likely reflect an understanding of the dangers of admitting Ukraine into the alliance. Rather than decrease the possibility of war, offering Ukraine NATO membership risks provoking a Russian military response which has the potential to instigate a larger war between the United States and a nuclear-armed Russia. Not only would such a scenario be devastating for Ukrainians, but it also could escalate to the nuclear level; therefore, avoiding this outcome should be a top policy priority. Even short of war, protracted hostility between the United States and Russia over Ukraine could spill over into other areas, costing the United States time and resources better devoted to higher priorities. Nevertheless, the United States and NATO continue to play to the edge of offering full membership, recognizing Ukraine as an Enhanced Opportunities Partner in 2020 and conducting joint military exercises as recently as September 2021 to increase Ukraine’s interoperability with NATO forces.7“NATO Recognizes Ukraine as Enhanced Opportunities Partner,” NATO, June 12, 2020, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/news_176327.htm; Pavel Polityuk, “Ukraine Holds Military Drills with U.S. Forces, NATO Allies,” Reuters, September 20, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/business/aerospace-defense/ukraine-holds-military-drills-with-us-forces-nato-allies-2021-09-20.

Continued U.S. security assistance to Ukraine and dangling false hopes of NATO membership prolong the conflict in Ukraine and increase the risk of counterproductive war between the United States and Russia. The Biden administration’s current policy draws out the suffering of Ukrainians and prevents the possibility of establishing stable and constructive relations between the world’s two greatest nuclear powers.

An overview of the conflict

Hostilities in Ukraine began in November 2013 when, under heavy pressure from Moscow, Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych rejected an association agreement that would have led to greater economic integration with the European Union.8“Conflict in Ukraine,” Council on Foreign Relations, September 13, 2021, https://www.cfr.org/global-conflict-tracker/conflict/conflict-ukraine. This decision sparked large protests in Kyiv against Yanukovych, which escalated tensions throughout Ukraine between citizens who preferred closer ties with Europe and those who preferred closer ties with Russia.

As protests intensified and became more violent, Yanukovych fled to Russia in February 2014. The following month, Russian forces seized, and ultimately annexed, the Crimean Peninsula.9“Conflict in Ukraine,” Council on Foreign Relations. Pro-Russian separatists, with Russian backing, fought Ukrainian security forces in the eastern Ukrainian regions of Donetsk and Luhansk. These two regions declared themselves independent from Ukraine following disputed local referendums in May 2014.10Larina Oganesyan, “Donetsk, Luhansk: The ‘People’s Republics’ One Year On,” Deutsche Welle, May 11, 2015, https://www.dw.com/en/donetsk-luhansk-the-peoples-republics-one-year-on/a-18444476.

As a result of a long-intertwined history, eastern Ukraine has strong cultural, economic, and political ties with Russia. These factors intensified the conflict, igniting a civil war between pro-Russian separatists and pro-Ukrainian security forces. A national census conducted in 2001 found that while 77 percent of Ukrainian citizens identify as ethnic Ukrainians, a sizable minority (17 percent) identify as ethnic Russians.11“All-Ukrainian Population Census 2001,” State Statistics Committee of Ukraine, accessed November 12, 2021, http://2001.ukrcensus.gov.ua/eng/results/general/nationality. The majority of those claiming Russian ethnicity reside in eastern and southern Ukraine. Indeed, ethnic Russians make up the majority of Crimea.12“World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples—Ukraine,” UNHRC, 2007, https://www.refworld.org/docid/4954ce5123.html. The Russian language is used extensively throughout the eastern and southern regions of the country, and 29 percent of Ukrainians consider Russian to be their first language.13“Russophone Identity in Ukraine,” Ukrainian Center for Independent Political Research, March 2017, http://www.ucipr.org.ua/publicdocs/RussophoneIdentity_EN.pdf. Survey data illuminates this geographical divide further: Ukrainians living in central and western Ukraine prefer closer relations with Europe while those residing in the south and east prefer closer relations with Russia.14Mike Sweeney, “Saying ‘No’ to NATO: Options for Ukrainian Neutrality,” August 2020, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/saying-no-to-nato-options-for-ukrainian-neutrality.

Diplomatic efforts so far have failed to end the violence. In September 2014, Ukrainian, Russian, and separatist leadership signed the Minsk Protocol, seeking to achieve a ceasefire and create the conditions necessary to resolve the conflict. The implementation of the agreement quickly broke down with both sides accusing the other of ceasefire violations.

In February 2015, a renewed effort in the form of Minsk II between the leaders of Ukraine, Russia, Germany, and France was agreed upon. Minsk II called for several conflict management measures, including a ceasefire and the pullback of heavy weaponry from the front line; amnesty for fighters; an exchange of hostages; humanitarian assistance; Ukraine resuming socio-economic ties with the Donbas region; the disarmament of all illegal groups; and the withdrawal of all foreign armed formations, mercenaries, and military equipment from the country. The agreement also attempted to address key political issues and called for Ukrainian authorities to reestablish full control over the Ukraine-Russia border, a dialogue on local elections in the Donbas region in accordance with Ukrainian law, and constitutional reform that would provide greater autonomy for the Donbas region.15“Package of Measures for the Implementation of the Minsk Agreements,” United Nations, February 12, 2015, https://peacemaker.un.org/ukraine-minsk-implementation15. Like its predecessor, Minsk II failed to end the conflict—ceasefire violations and sporadic heavy fighting have continued since 2015.16“Ukraine: The Minsk Agreements Five Years On,” European Parliament, March 2020, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/ATAG/2020/646203/EPRS_ATA(2020)646203_EN.pdf.

Geography is destiny for Ukraine

Ukraine must live within the politics of its geography. Kyiv’s ability to manage its foreign affairs is largely dictated by the country’s location.

The conflict remains frozen with neither side claiming new territory for several years. The 260-mile-long contact line runs across the Donbas region, effectively splitting the country into east and west. Both sides implement restrictions on civilian movement, and the overall security situation remains volatile. While the intensity of the fighting has died down from the initial stages of the conflict, the possibility of further escalation remains high with 250 ceasefire violations (mostly small arms fire and shelling) per day observed in September 2021.17“OSCE Says September Sees Peak Number of Ceasefire Breaches in Donbas since July 2020,” Ukrinform, accessed November 10, 2021, https://www.ukrinform.net/rubric-defense/3324607-osce-says-september-sees-peak-number-of-ceasefire-breaches-in-donbas-since-july-2020.html. So far, the war has killed more than 14,000 people and wounded more than 30,000. More than 1.6 million Ukrainians were internally displaced because of the fighting.18“Conflict in Ukraine’s Donbas: A Visual Explainer,” International Crisis Group, accessed November 12, 2021, https://www.crisisgroup.org/content/conflict-ukraines-donbas-visual-explainer; “Conflict in Ukraine Enters Its Fourth Year with No End In Sight—UN Report,” Office of the High Commissioner, United Nations Human Rights, June 13, 2017, https://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=21730; “Death Toll Up to 13,000 in Ukraine Conflict, Says UN Rights Office,” Radio Free Europe Radio Liberty, February 26, 2019, https://www.rferl.org/a/death-toll-up-to-13-000-in-ukraine-conflict-says-un-rights-office/29791647.html.

Why current U.S. policy is not working

Given the significant power disparity between Ukraine and Russia, U.S. military aid does little but prolong a civil war and heighten U.S.-Russia tensions. Modestly increasing the capabilities of Ukraine’s military forces by providing high-tech equipment and lethal weaponry provides a minuscule benefit at the expense of a vast risk.

Providing military aid risks a tit-for-tat escalation with Russia as Moscow can assist its proxies in kind, essentially canceling out any U.S. efforts. Security aid that provides Ukraine an opportunity to retake contested territory could escalate the conflict to the point where Moscow may commit overt conventional military forces in support of the separatists. Moscow has periodically moved tens of thousands of troops to the Ukrainian border, reminding Kyiv that it is outmatched militarily. In Spring 2021, Russia stationed close to 80,000 troops near Ukraine’s border at the same time as major NATO exercises were being conducted in eastern Europe.19Helene Cooper and Julian E. Barnes, “80,000 Russian Troops Remain at Ukraine Border as NATO Holds Exercise,” New York Times, May 5, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/05/us/politics/biden-putin-russia-ukraine.html. In November 2021, Russia stationed 90,000 troops near Ukraine’s borders, signaling again its military superiority.20Yuras Karmanau, “Ukraine Now Says 90,000 Russian Troops Not Far from Border,” Associated Press, November 3, 2021, https://apnews.com/article/europe-russia-ukraine-f356c933c1ac8993aee383ed30d1e017. A direct conflict with Russia would surely prove devastating for Ukraine.

Supporters of providing U.S. security aid might argue Ukraine need not defeat Russia in the event of a full-scale invasion. Rather, the goal should be to deter further Russian aggression by inflicting significant damage to Russian military forces. The United States provided Javelin missiles and Mark VI patrol boats explicitly with the intention of deterring Russian armor and naval threats.21“U.S. Security Cooperation with Ukraine,” U.S. Department of State, July 2, 2021; Lara Seligman and Natasha Bertrand, “Can Ukraine Deploy U.S.-Made Weapons against the Russians?” Politico, April 12, 2021, https://www.politico.com/news/2021/04/12/ukraine-us-missile-weapons-russia-480985. Besides being dismissive of the brutal consequences to Ukrainians, this line of thinking omits the reality that Moscow views the prevention of a pro-western Ukraine as a core strategic interest.22Tom Balforth, “Kremlin Says NATO Expansion in Ukraine Is a ‘Red Line’ for Putin,” Reuters, September 27, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/world/kremlin-says-nato-expansion-ukraine-crosses-red-line-putin-2021-09-27. Russia will therefore go to great lengths to prevent that outcome. Despite years of tough economic sanctions from the United States and Europe, Russia’s primary aims and its resolve in Ukraine remain unchanged. The historical record also suggests Russia will tolerate great military costs in pursuit of national security, as evident by World War II, the Soviet-Afghan War, and the Chechen Wars. More recently, Moscow demonstrated its resolve to use military force in Georgia, Syria, and parts of Ukraine. As many as 500 Russian personnel died in Ukraine in the first year after the annexation of Crimea, according to the U.S. State Department.23“U.S. Policy in Ukraine: Countering Russia and Driving Reform,” Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, U.S. Senate, March 10, 2015, https://www.foreign.senate.gov/hearings/us-policy-in-ukraine-countering-russia-and-driving-reform-03-10-15. Given Russia’s view of Ukraine’s significance to its security, one can reasonably expect Russian forces will bear a substantial burden to prevent a western-oriented Ukraine.

Moreover, U.S. and European leaders have naively strung along Ukraine with the notion it may one day join NATO.24“Poland and Other NATO Countries Support Granting Ukraine MAP—Duda,” Ukrinform, April 5, 2021, https://www.ukrinform.net/rubric-polytics/3239770-poland-and-other-nato-countries-support-granting-ukraine-map-duda.html; Ben Wolfgang, “Open Door to NATO for Georgia, Ukraine as Pentagon Chief Austin Visits Eastern Europe,” Washington Times, October 17, 2021, https://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2021/oct/17/open-door-nato-georgia-ukraine-pentagon-chief-aust. This would be a tremendous miscalculation—Russia has made it clear it views accession as a “red line” the West should not cross.25Tom Balforth, “Kremlin Says NATO Expansion in Ukraine Is a ‘Red Line’ for Putin.” Failing to rule out Ukrainian membership in NATO risks a sudden Russian attack on Ukraine, with the potential of igniting a major NATO-Russia conflict. With Russia already at war in eastern Ukraine, acceptance into the alliance could immediately trigger NATO’s Article 5 and bring the United States and all other NATO allies to militarily defend Ukraine. Such a scenario could quickly escalate to the nuclear level, making it imperative western policy makers honestly assess the devastating consequences that could follow such a misguided policy.

Reaching a realistic resolution in the U.S. interest

Unlike Russia, the United States does not have a strong security interest in Ukraine that would provide an impetus for U.S. service members to fight and die over it. The United States does, however, have a strong incentive to lower the risk of war with Russia and work toward improved U.S.-Russia relations. On humanitarian grounds, it would also be good to avoid prolonging the suffering of Ukrainians.

Ending the conflict requires a political settlement that accounts for the geopolitical anxiety of Russia. One need not agree with Russia’s concerns, but accounting for them is necessary to ensure a prudent Ukraine policy. U.S. and European leaders should pursue a policy that would see Ukraine become a neutral buffer state, neither aligned with Russia nor the West.26Mike Sweeney, “Saying ‘No’ to NATO-Options for Ukrainian Neutrality.” A neutral Ukraine would not seek integration with western or Russian security institutions, nor would it allow either side to utilize its territory for military purposes. Rather, it would tactfully reflect its precarious geographical reality—being a large but relatively weak state situated on the border of a great nuclear power. The United States has two main levers to incentivize Russia and Ukraine to bring about this resolution: Ending the possibility of Ukraine becoming a NATO member and halting direct security aid to Ukraine.

A neutral status would not preclude Ukraine from establishing stronger trade ties with the United States, other European countries, and Russia; however, it would require taking NATO expansion off the table.27While Russia opposes Ukraine’s European Union aspirations, it is unlikely that their interests would be threatened by trade that does not come with institutional ties. Preventing Ukraine from joining NATO enhances U.S. security by reducing the risk of war with nuclear-armed Russia over a territory with little geopolitical significance to the United States—keeping Ukraine out of NATO also happens to be Russia’s primary objective. Even without a formal membership action plan for Ukraine to join NATO, rhetoric of potential membership from U.S. and European leaders counterproductively incentivizes Russia to continue its interference in Ukraine. Such rhetoric should stop, otherwise Russia will seek to keep Ukraine divided to prevent NATO accession and will maintain the possibility of further escalation, if needed, to do so.

The United States should cease direct security aid, and in particular lethal aid, as it has protracted the conflict, can be equally matched by Russia, and risks further escalation. Given the imbalance of power between Russia and Ukraine, the United States cannot realistically provide enough security aid to tip the scale in Ukraine’s favor at an acceptable level of cost and risk. Security aid may also have unintended escalatory consequences should Ukrainian forces gain an acute military advantage over the separatists. Moscow may commit overt military forces should it believe Ukraine will attempt to retake contested territory. Moreover, U.S. security aid makes Ukraine more dependent on the wherewithal of the United States to continue the conflict, shifting Ukraine’s security burden to American taxpayers.

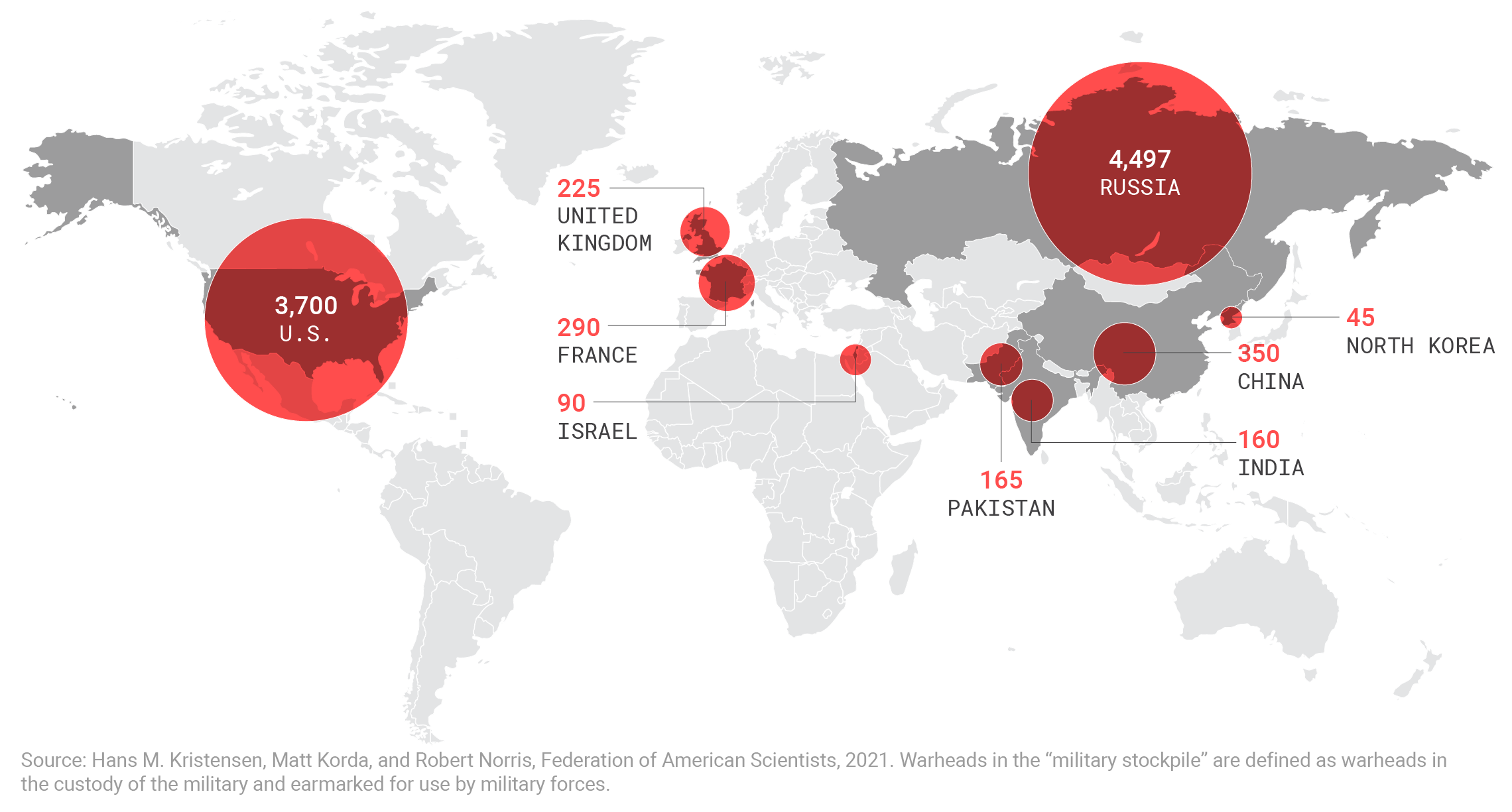

Number of nuclear weapons in each country’s military stockpile

The U.S. and Russia hold nearly nine of every 10 deployed and stored nuclear warheads in the world. Avoiding a nuclear conflict remains the highest U.S. national security priority with respect to Russia.

Providing hope to Ukraine that NATO will come to its defense, including by continuing U.S. security aid, allows Kyiv to avoid making difficult political accommodations necessary to end the war.28Ben Friedman, “Biden Doesn’t Like Russia’s Meddling in Ukraine. But He’s Not Prepared to Stop It,” NBC News, May 6, 2021, https://www.nbcnews.com/think/opinion/biden-doesn-t-russia-s-meddling-ukraine-he-s-not-ncna1266535. A political settlement will likely necessitate that Ukraine accepts its unique role as a neutral buffer state in Eastern Europe. The prospect of being protected forever by the United States lets Ukrainian leaders avoid pressing for a resolution to the conflict.

A settlement could result in Russia ending its support for separatist groups in the Donbas region, allowing Ukraine to work toward national reconciliation. Russia and European countries should take responsibility for providing significant humanitarian and economic aid to help those affected by the conflict. War-torn areas will need assistance rebuilding vital infrastructure to allow displaced citizens to return home and normal economic activity to resume. Since the civil strife has been partly fueled by ethnic and cultural tensions, a neutral Ukraine should also be encouraged to protect minority rights and increase local autonomy for the Donbas region.

The Ukraine crisis has poisoned U.S.-Russia relations for the last seven years, a dangerous status quo given the importance of avoiding conflict between nuclear weapons states. Sympathy for Ukraine’s unfortunate geopolitical circumstances is natural; however, current policy undermines U.S. security and exacerbates the suffering of Ukrainians. Working toward a realistic resolution in the form of a neutral, non-aligned Ukraine could provide an avenue for the United States and Russia to form a constructive and predictable relationship. As the United States shifts its focus to the greater threat of China, détente with Russia should guide U.S. policy.29Daniel DePetris, “Perils of Pushing Russia and China Together,” Defense Priorities, August 2021, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/perils-of-pushing-russia-and-china-together.

Endnotes

- 1“Joint Statement on the U.S.-Ukraine Strategic Partnership,” White House, September 1, 2021, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/09/01/joint-statement-on-the-u-s-ukraine-strategic-partnership.

- 2“Joint Statement on the U.S.-Ukraine Strategic Partnership,” White House.

- 3“U.S. Security Cooperation with Ukraine,” U.S. Department of State, July 2, 2021, https://www.state.gov/u-s-security-cooperation-with-ukraine.

- 4“U.S. Security Cooperation with Ukraine,” U.S. Department of State.

- 5Matthias Williams and Pavel Polityuk, “Russia Is Obstacle to Peace in East Ukraine—U.S. Defence Secretary,” Reuters, October 19, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/russia-cannot-block-ukraines-nato-aspirations-us-secretary-defence-says-2021-10-19/.

- 6Isabelle Khurshudyan, “Ahead of White House Meeting, Ukraine’s Zelensky Expresses Frustration with Western Allies,” Washington Post, August 19, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/europe/ukraine-zelensky-interview-russia/2021/08/19/93b475e6-fabe-11eb-911c-524bc8b68f17_story.html.

- 7“NATO Recognizes Ukraine as Enhanced Opportunities Partner,” NATO, June 12, 2020, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/news_176327.htm; Pavel Polityuk, “Ukraine Holds Military Drills with U.S. Forces, NATO Allies,” Reuters, September 20, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/business/aerospace-defense/ukraine-holds-military-drills-with-us-forces-nato-allies-2021-09-20.

- 8“Conflict in Ukraine,” Council on Foreign Relations, September 13, 2021, https://www.cfr.org/global-conflict-tracker/conflict/conflict-ukraine.

- 9“Conflict in Ukraine,” Council on Foreign Relations.

- 10Larina Oganesyan, “Donetsk, Luhansk: The ‘People’s Republics’ One Year On,” Deutsche Welle, May 11, 2015, https://www.dw.com/en/donetsk-luhansk-the-peoples-republics-one-year-on/a-18444476.

- 11“All-Ukrainian Population Census 2001,” State Statistics Committee of Ukraine, accessed November 12, 2021, http://2001.ukrcensus.gov.ua/eng/results/general/nationality.

- 12“World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples—Ukraine,” UNHRC, 2007, https://www.refworld.org/docid/4954ce5123.html.

- 13“Russophone Identity in Ukraine,” Ukrainian Center for Independent Political Research, March 2017, http://www.ucipr.org.ua/publicdocs/RussophoneIdentity_EN.pdf.

- 14Mike Sweeney, “Saying ‘No’ to NATO: Options for Ukrainian Neutrality,” August 2020, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/saying-no-to-nato-options-for-ukrainian-neutrality.

- 15“Package of Measures for the Implementation of the Minsk Agreements,” United Nations, February 12, 2015, https://peacemaker.un.org/ukraine-minsk-implementation15.

- 16“Ukraine: The Minsk Agreements Five Years On,” European Parliament, March 2020, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/ATAG/2020/646203/EPRS_ATA(2020)646203_EN.pdf.

- 17“OSCE Says September Sees Peak Number of Ceasefire Breaches in Donbas since July 2020,” Ukrinform, accessed November 10, 2021, https://www.ukrinform.net/rubric-defense/3324607-osce-says-september-sees-peak-number-of-ceasefire-breaches-in-donbas-since-july-2020.html.

- 18“Conflict in Ukraine’s Donbas: A Visual Explainer,” International Crisis Group, accessed November 12, 2021, https://www.crisisgroup.org/content/conflict-ukraines-donbas-visual-explainer; “Conflict in Ukraine Enters Its Fourth Year with No End In Sight—UN Report,” Office of the High Commissioner, United Nations Human Rights, June 13, 2017, https://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=21730; “Death Toll Up to 13,000 in Ukraine Conflict, Says UN Rights Office,” Radio Free Europe Radio Liberty, February 26, 2019, https://www.rferl.org/a/death-toll-up-to-13-000-in-ukraine-conflict-says-un-rights-office/29791647.html.

- 19Helene Cooper and Julian E. Barnes, “80,000 Russian Troops Remain at Ukraine Border as NATO Holds Exercise,” New York Times, May 5, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/05/us/politics/biden-putin-russia-ukraine.html.

- 20Yuras Karmanau, “Ukraine Now Says 90,000 Russian Troops Not Far from Border,” Associated Press, November 3, 2021, https://apnews.com/article/europe-russia-ukraine-f356c933c1ac8993aee383ed30d1e017.

- 21“U.S. Security Cooperation with Ukraine,” U.S. Department of State, July 2, 2021; Lara Seligman and Natasha Bertrand, “Can Ukraine Deploy U.S.-Made Weapons against the Russians?” Politico, April 12, 2021, https://www.politico.com/news/2021/04/12/ukraine-us-missile-weapons-russia-480985.

- 22Tom Balforth, “Kremlin Says NATO Expansion in Ukraine Is a ‘Red Line’ for Putin,” Reuters, September 27, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/world/kremlin-says-nato-expansion-ukraine-crosses-red-line-putin-2021-09-27.

- 23“U.S. Policy in Ukraine: Countering Russia and Driving Reform,” Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, U.S. Senate, March 10, 2015, https://www.foreign.senate.gov/hearings/us-policy-in-ukraine-countering-russia-and-driving-reform-03-10-15.

- 24“Poland and Other NATO Countries Support Granting Ukraine MAP—Duda,” Ukrinform, April 5, 2021, https://www.ukrinform.net/rubric-polytics/3239770-poland-and-other-nato-countries-support-granting-ukraine-map-duda.html; Ben Wolfgang, “Open Door to NATO for Georgia, Ukraine as Pentagon Chief Austin Visits Eastern Europe,” Washington Times, October 17, 2021, https://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2021/oct/17/open-door-nato-georgia-ukraine-pentagon-chief-aust.

- 25Tom Balforth, “Kremlin Says NATO Expansion in Ukraine Is a ‘Red Line’ for Putin.”

- 26Mike Sweeney, “Saying ‘No’ to NATO-Options for Ukrainian Neutrality.”

- 27While Russia opposes Ukraine’s European Union aspirations, it is unlikely that their interests would be threatened by trade that does not come with institutional ties.

- 28Ben Friedman, “Biden Doesn’t Like Russia’s Meddling in Ukraine. But He’s Not Prepared to Stop It,” NBC News, May 6, 2021, https://www.nbcnews.com/think/opinion/biden-doesn-t-russia-s-meddling-ukraine-he-s-not-ncna1266535.

- 29Daniel DePetris, “Perils of Pushing Russia and China Together,” Defense Priorities, August 2021, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/perils-of-pushing-russia-and-china-together.

Author

Sascha

Glaeser

Former Research Associate

More on Eurasia

By John Mueller

April 10, 2025

Featuring Lyle Goldstein

April 1, 2025

Events on Russia