July 19, 2022

War is a choice, not a trap: the right lessons from Thucydides

Key points

- A careful reading of the Greek Thucydides’ The History of the Peloponnesian War suggests that a U.S.-China war is hardly inevitable.

- Such a war is a choice, not a trap, and selecting the appropriate U.S. grand strategy is the way to avoid it.

- China faces important geographical and technological obstacles to expanding its hegemonic position in the region.

- Thucydides’ fundamental lessons for the contemporary United States in its rivalry with China is that democratic Athens erred when it sought primacy by expanding its empire during the Peloponnesian War; today we do not need to preserve a position of primacy in East Asia but can instead rest content with maintaining a balance of power.

- Despite China’s rise, the United States and its regional allies are in a strong position to maintain a regional balance of power that keeps a peace and serve U.S. interests in Asia.

Taking the right lessons from Tucydides

Thucydides claimed that his history would be relevant for all time. He was confident his work would survive his passing because he believed he had identified certain permanent features of human nature and statecraft that would remain relevant despite dramatic changes in technology and other elements of the modern world.1Robert B. Strassler, ed., The Landmark Thucydides: A Comprehensive Guide to the Peloponnesian War (New York: The Free Press, 1996), 1.22.4. His bold prediction of his book’s enduring value may strike readers as intellectual hubris—but its impact upon the ancient Romans; Thomas Hobbes during the English Civil War; the American Founders (both as a positive and negative example), particularly John Adams and John Quincy Adams; Edward Everett’s Gettysburg Address; and even the newly unified Germany of the late nineteenth century is testament to the failed Athenian general’s success at remaining relevant.2In addition to Plutarch’s Lives and Hobbes’ translation of Thucydides, see Carl J. Richard, The Founders and the Classics: Greece, Rome, and the American Enlightenment (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1994) and Thomas E. Ricks, First Principles: What America’s Founders Learned From the Greeks and Romans and How That Shaped Our Country (New York: Harper, 2020); Charles N. Edel, Nation Builder: John Quincy Adams and the Grand Strategy of the Republic (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2014), 18–22; Garry Wills, Lincoln at Gettysburg: The Words That Remade America (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1992); and Hans Delbrücke, Die Strategie des Perikles erläutert durch die strategie Friedrichs des Grossen. Mit einem anhang über Thueydides und Kleon (Berlin: G. Reimer, 1890).

The book’s Cold War relevance to the United States was widely recognized. As Secretary of State George Marshall told the Princeton class of 1947, “I doubt seriously whether a man can think with full wisdom and with deep conviction regarding certain of the basic issues today who has not at least reviewed in his mind the period of the Peloponnesian War and the Fall of Athens.”3“Speech at Princeton, February 22, 1947” at https://www.marshallfoundation.org/articles-and-features/marshall-plan-princeton-speech/. Also see State Department Official Louis J. Halle, Civilization and Foreign Policy: An Inquiry for Americans (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1975 [1952]), Appendix: “A Message from Thucydides.” If anything, it is even more relevant to the post-Cold War United States.4Making this argument are Danielle S. Allen, “The Aims of Education Address 2001,” University of Chicago, September 20, 2001, https://college.uchicago.edu/student-life/aims-education-address-2001-danielle-s-allen; George Bornstein, “Reading Thucydides in America Today,” Sewanee Review 123, no. 4 (Fall 2015): 661–667. It describes the continuing domestic and international challenges a democracy faces in playing a leading role in great power politics, especially when it is a dominant hegemon. It also prescribes concrete policies that might make it possible for contemporary America to square the strategic circle ancient Athens never could.

A Thucydides’ trap?

The most widely discussed contemporary work using Thucydides as a guide for twenty-first century grand strategy is Graham Allison’s Destined for War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides’ Trap?5Graham Allison, “The Thucydides Trap: Are the U.S. and China Headed for War?” Atlantic, September 24, 2015, https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2015/09/united-states-china-war-thucydides-trap/406756/; Graham Allison, Destined for War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides’ Trap? (Boston, MA: Mariner Books, 2018). Like power transition theorists, Allison regards the decline of existing hegemonic powers and the rise of new ones as a major source of great power conflict and war.6Robert Gilpin, “The Theory of Hegemonic War,” The Journal of Interdisciplinary History 18, no. 4 [The Origin and Prevention of Major Wars] (Spring 1988): 591–613; A.F.K. Organski and Jacek Kugler, The War Ledger (Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press, 1980), 19–22. Also see Mark Kauppi, “Thucydides: Character and Capabilities,” Security Studies 5, no. 2 (Winter 1995): 142; William C. Wohlforth, “Gilpinian Realism and International Relations,” International Relations 25, no. 4 (December 2011): 499–511. Richard Ned Lebow, “Thucydides, Power Transition Theory, and the Causes of War” in Hegemonic Rivalry, eds. Richard Ned Lebow and Barry Strauss (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1991), 125–165 rejects the PTT account of the origins of the Peloponnesian War on the grounds that Athens’ power was not in fact growing. Indeed, by his calculation, in three quarters of such cases rising and declining great powers became entrapped in war.7Allison, Destined for War, 42. It is not surprising Allison and others would look to the Peloponnesian War because here is evidence that another power transition is going on with China “rising” relative to the United States in many direct and latent indicators of national power.8Also see Robert B. Zoellick, “U.S., China, and Thucydides,” National Interest, no. 126 (July/August 2013): 22–30. I find Joshua Itzkowitz Shifrinson’s part of his correspondence with Michael Beckley in “Debating China’s Rise and Decline,” International Security 37, no. 3 (Winter 2012/13): 172–177 makes a compelling case that China is indeed a “rising” power and closing the gap with the United States in some important measures of power. China, once a hierarchical power in East Asia, seems bent on reestablishing something like that today.9David C. Kang, “Hierarchy and Legitimacy in International Systems: The Tribute System in Early Modern Asia,” Security Studies 19, no. 4 (2010): 591–622. How would Thucydides recommend that the United States respond?

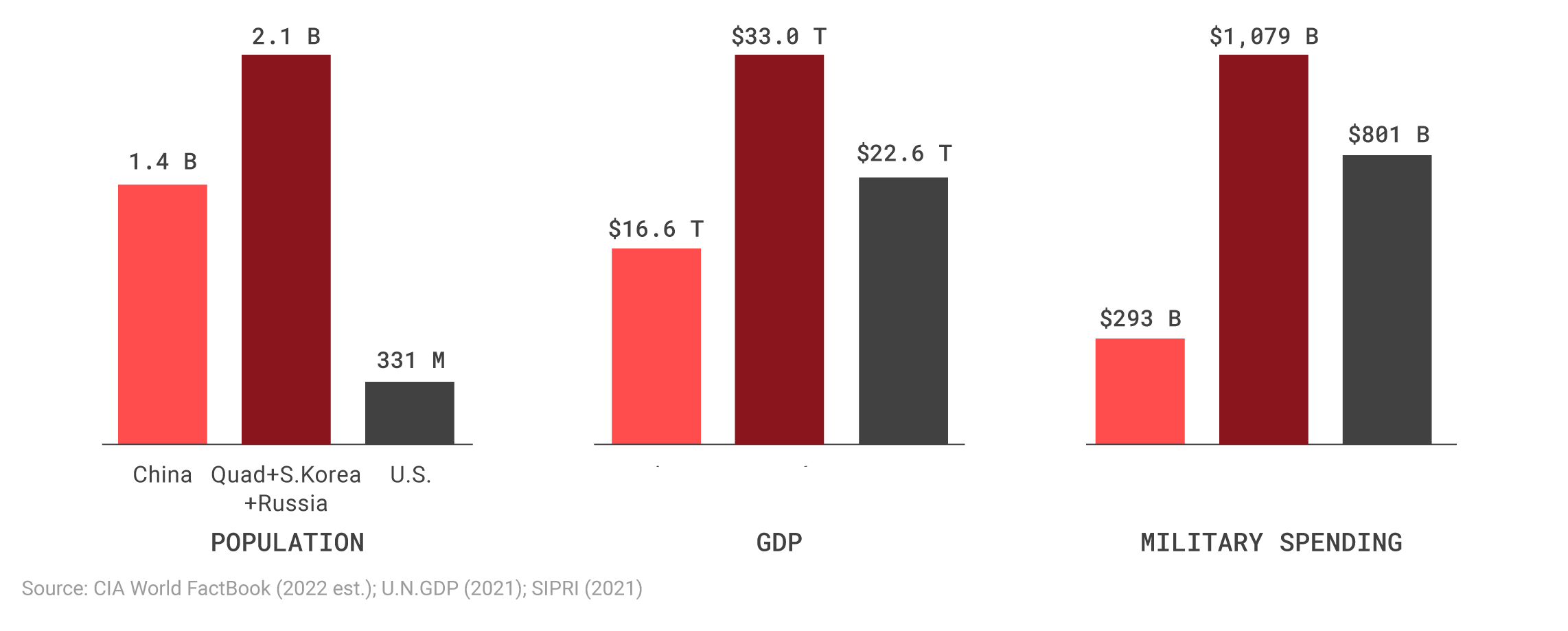

The Quad, South Korea, and Russia vs. China by indicators of national power

As China rises and narrows the relative power advantage of the United States, Thucydides offers insights into how the United States should respond. A careful reading of Thucydides suggests that a balance, rather than trying to maintain preponderance, should be sufficient to protect U.S. interests.

Criticism of Allison’s take on Thucydides has become something of a cottage industry. Not all Western scholars would go so far as Jonathan Kirshner in dismissing Destined for War out of hand as “sloppy, superficial, oversimplified, overconfident, and repetitive,” but it is fair to say many found much wanting in the book.10Jonathan Kirshner, “Handle Him With Care: The Importance of Getting Thucydides Right,” Security Studies 28, no. 1 (January–March 2019): 12. Nor have Chinese leaders or scholars found the analogy between the great war between Athens and Sparta and the twenty-first century U.S.-China rivalry useful, save perhaps as an indicator of how America views their rise. Chinese President Xi Jinping categorically denied there is any “such thing as the so-called Thucydides trap in the world.”11“Speech by H.E. Xi Jinping,” Welcoming Dinner Hosted by Local Governments and Friendly Organizations in the United States, September 24, 2015, https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/topics_665678/2015zt/xjpdmgjxgsfwbcxlhgcl70znxlfh/201510/t20151013_705321.html. The majority of Chinese scholars “reject the so-called metaphor from history and regard this simplistic historical analogy as the newest version of the longstanding ‘China Threat Theory.’”12Mo Shengkai and Chen Yue, “The U.S.-China ‘Thucydides Trap’: A View From Beijing,” National Interest, July 10, 2016, https://nationalinterest.org/print/feature/the-us-china-thucydides-trap-view-beijing-16903. China Threat Theory is an umbrella under which a number of arguments come together about why China’s rise is not likely to be peaceful.13Emma V. Broomfield, “Perceptions of Danger: The China Threat Theory,” Journal of Contemporary China 12, no. 35 (August 2010): 265–284. Not to pile on, but Allison’s use of Thucydides is muddled. Allison himself puts this slightly differently: He admits he holds “two contradictory ideas in [his] head at the same time.”14John Mecklin, “Interview with Graham Allison: Are the United States and China charging into Thucydides’ trap?” Bulletin of Atomic Scientists, March 10, 2022, https://thebulletin.org/premium/2022-03/interview-with-graham-allison-are-the-united-states-and-china-charging-into-thucydidess-trap/. Either way, Allison is not clear on some important points as to how we ought to think about the U.S.-China rivalry through Thucydides’ lens.

A trap or a choice?

For instance, he is equivocal about what he means by a “trap.” In some places he suggests “destiny” is not “inevitability,” and smart leadership can avoid this geopolitical snare.15Allison, Destined for War, 187–213 and 287. But in other places, Allison notes the trap defied “the ancient world’s two most fabled powers’” leaders’ efforts to “avoid” war. Elsewhere, he adds the Thucydides trap “create[s] a dynamic that is extremely difficult to manage successfully.”16Mecklin, “Interview with Graham Allison.” If not “inevitable,” war between the United States and China is highly probable given his gloss on the history of great power conflict.17Allison, Destined for War, 30 and 39–40. Indeed, in his assessment of 500 years of the rise and fall of great powers he calculates 75 percent of the time rising and declining powers come to blows.18Allison, Destined for War, 42. Given that, it is not surprising the title of his book is Destined for War.

Allison’s muddle on this issue may in part reflect the debate among scholars and translators about Thucydides’ own views of the “inevitability” of the great war between Athens and Sparta. The famous Crawley translation of section 1.23.6 translates Thucydides as declaring “the growth of the power of Athens, and the alarm which this inspired in Sparta, made war inevitable” (emphasis added).19Landmark Thucydides, 123.6.; Allison, Destined for War, xiv. Other translations, though, are far less determinative. Jeremy Mynott, for example, translates Thucydides as suggesting “the Athenians were becoming powerful and inspired fear in the Spartans and so forced them into war.”20The Jeremy Mynott translation of Thucydides, The War of the Peloponnesians and the Athenians (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 1.23.6. I agree, therefore, with Arthur M. Eckstein that Thucydides did not mean the war is “inevitable” absent decisions of the leaders of Sparta and especially Athens, so the widely used Richard Crawley translation is misleading on this score.21Arthur M. Eckstein, “Thucydides, the Outbreak of the Peloponnesian War, and the Foundation of International Systems Theory,” The International History Review 25, no. 4 (December 2003): 757–774. Arlene Saxenhouse concedes there is what she calls a “power trap” in Thucydides—fear makes the powerful pursue yet more power to counter the power-seeking of others, resulting in a spiral of conflict—but notes neither Thucydides nor his hero Pericles thought all-out, catastrophic war was inevitable.22Arlene W. Saxonhouse, “Kinēsis, Navies, and the Power Trap in Thucydides” in Ryan K. Balot, Sara Forsdyke, and Edith Foster, eds., The Oxford Handbook of Thucydides (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017), 351. Indeed, in his famous eulogy for Pericles in Book II, Thucydides praises Pericles’ strategic prudence and deplores the lack of it among his successors, thereby suggesting a major role for choice.23Landmark Thucydides, 2.65.6-7 and 10–11.

Relatedly, in some places, Allison seems to advocate some elements of a Balance of Power-type strategy as means to avert U.S.-China conflict; but elsewhere in the book he indicts realpolitik as part of the problem, associating it with the later Athenian thesis at Melos—”the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must”24Landmark Thucydides, 5.89.1.—and perhaps tying it to those contemporary analysts who think that the way the U.S. should respond to the rise of China is to keep it down.25Compare Allison, Destined for War, 235–238 with footnote 38. Given that, the balance of power realist case for how to deal with a rising China still remains to be made.

U.S. grand strategic options today

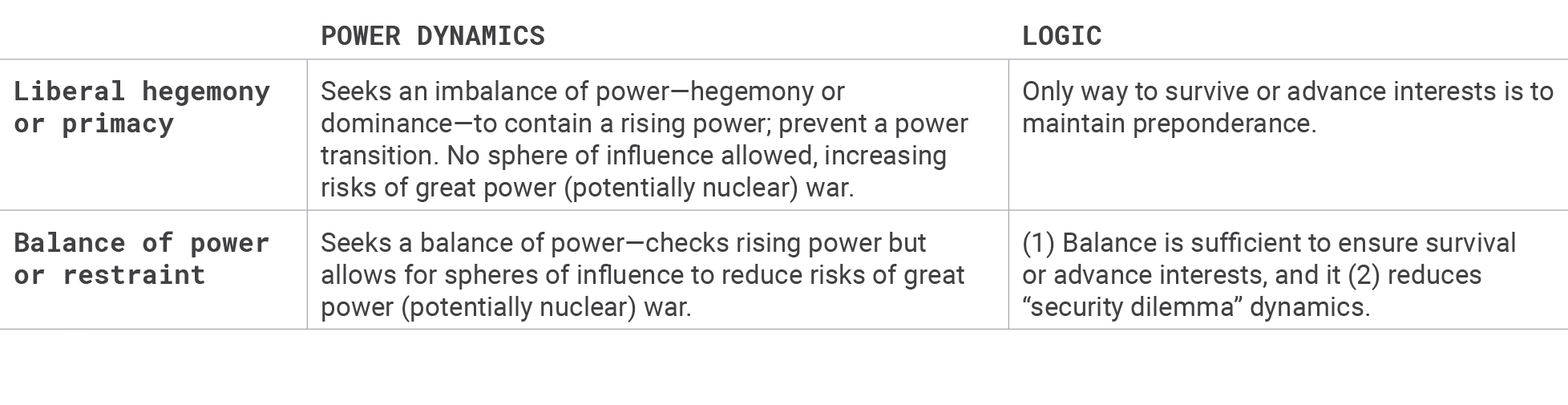

What are the strategic choices available to the United States to deal with the rise of China? There are essentially two: One approach, which is widely embraced within the U.S. government and endorsed by many pundits and scholars, is that the way to avoid hegemonic war is to avert power transition altogether by maintaining U.S. dominance. Indeed, the notion we need to contain or otherwise stay ahead of China dominates much official thinking in Washington, DC. This could be done unilaterally by simply staying as far ahead of the Chinese as possible in terms of both direct and latent indices of power. This is the power maximization of grand strategies like “primacy.”26Richard Bernstein and Ross H. Munro, “The Coming Conflict With America,” Foreign Affairs 76, no. 2 (March/April 1997): 18-32 make the baldest case for this power maximalist approach to China. Aaron L. Friedberg, A Contest for Supremacy: China, America, and the Struggle for Mastery in Asia (New York: W.W. Norton 2011), 274–284 urges the United States to preserve a “favorable balance of power,” by which he clearly means U.S. hegemony. Predicting that the United States will try to maintain its power advantage over China and endorsing “containment” as a means of doing so is John J. Mearsheimer, “Can China Rise Peacefully?” National Interest, October 25, 2014, https://nationalinterest.org/commentary/can-china-rise-peacefully-10204. Finally, arguing that this will be easy because the U.S. is so far ahead of China are Michael Beckley, “China’s Century? Why America’s Edge Will Endure,” International Security 36, no. 23 (Winter 2011/12): 41–78 and Stephen G. Brooks and William C. Wohlforth, “The Once and Future Superpower: Why China Won’t Overtake the United States,” Foreign Affairs 95, no. 3 (May/June 2016): 91–104. However, the more widely embraced strategy for maintaining U.S. hegemony these days is to emphasize its collective benefits and constrain its power through international institutions. Both “deep engagement” (the forward deployment of U.S. power to directly manage the international system) and “liberal internationalism” (the use of international institutions by the United States to do so) employ versions of this argument.27The Hegemonic Stability case for continuing U.S. leadership was expanded and applied to the People’s Republic of China in Zalmay M. Khalilizad, Abram N. Shulsky, Daniel L. Byman, Roger Cliff, David T. Orletsky, David Shlapak, and Ashley Tellis, The United States and a Rising China: Strategic and Military Implications (Santa Monica, CA: The RAND Corporation, 1999), 69–75. For an illustration of how easily Liberals can embrace this basic logic, see G. John Ikenberry, “The Rise of China and the Future of the West: Can the Liberal System Survive?” Foreign Affairs 87, no. 1 (January/February 2008): 23–37.

The other approach would set a more realistic goal for the United States in response to the rise of China: work to maintain a balance of power. This choice, in turn, hinges on a central issue in international relations theory: Is a concentration of power the natural equilibrium, hence it is the case that great powers, and perhaps lesser powers, should seek hegemony? Or is a balance of power the best situation and the most that great powers can reasonably aspire to and maintain?28Paul C. Avey, Jonathan N. Markowitz, and Robert Reardon, “Disentangling Grand Strategy: International Relations Theory and U.S. Grand Strategy,” Texas National Security Review 2, no. 1 (November 2018): 30. Table 1 nicely summarize the basic theoretical fault-line undergirding post-Cold War grand strategy debates as being between proponents of power maximization as opposed to power balancers. The “balance of power” refers to an equilibrium of peace between states or groups of them maintained by the military policies of each side.29In balance of power theory, the balance of power is both a prediction about what states will seek to secure themselves and also a normative objective, a way to keep the peace by matching strength with strength, rather than seeking dominance, an imbalance likely to prove dangerous due to fear on the weaker side and potentially destabilizing security dilemmas. See Barry R. Posen, The Sources of Military Doctrine: France, Britain, and Germany between the World Wars (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1984), 59–74. The latter is the lesson readers should take away from Thucydides’ chronicle of the great war between Athens and Sparta.

Liberal hegemony/primacy vs. balance of power/restraint

A careful reading of Thucydides shows that he inclines toward the latter view. Power maximization strategies are unsustainable because they tempt powerful states to overreach, as Athens did in Sicily in Books VI and VII. Given that propensity, other actors will balance against it, as do Sparta and its allies in the Peloponnesian League in Book I, the Sicilian Greek colonies in Books VI and VII, and dissatisfied members of the Athenian empire in Book VIII. Thucydides is also skeptical that benign hegemony is a stable situation long-term. Athens, which led the Greeks against the Persians and founded the Delian League as a voluntary alliance, soon gave way to the tyranny that reached its nadir at the Melian Dialogue in Book V. Given that, Thucydides’ message, while not identical to a restrained balance of power realism, seems most compatible with it.30For a similar reading, see Patrick Porter, “Thucydides Was a Realist,” Engelsberg Ideas, April 1, 2022, https://engelsbergideas.com/essays/in-defence-of-thucydides-the-realist/.

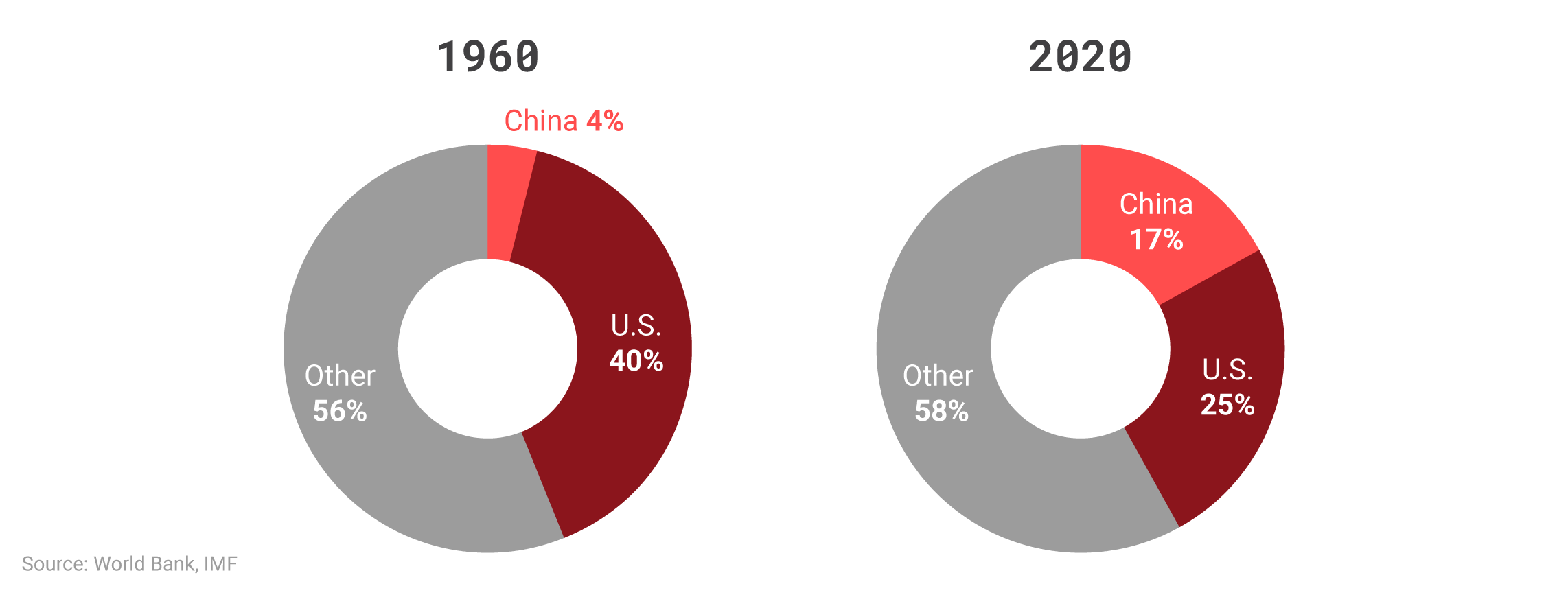

Such a reading of Thucydides suggests U.S. efforts to maintain its hegemonic position, either unilaterally or through popular consent, are bound to fail.31Christopher Layne, “This Time It’s Real: The End of Unipolarity and the ‘Pax Americana,’” International Studies Quarterly 56, no. 1 (March 2012): 203–213. The post-Cold War “unipolar moment” is an artifact of the sudden and unexpected collapse of one pole in a bipolar system. By virtue of its large population and high level of economic growth, China is soon to replace the Soviet Union as another pole in the twenty-first century international system. The interesting question now is not how much longer unipolarity will last but whether it will be replaced with a bipolar or multipolar system. And if it in fact turns out to be bipolar, why would not structural theory lead us to see how it might be stable—defined in terms of the absence of great power war—in the same way the Cold War was?32The classic articulation of this argument remains Kenneth N. Waltz, “The Stability of a Bipolar World,” Daedalus 93, no. 3 (Summer 1964): 881–909. I thank William Ruger for this observation. For a less sanguine view of bipolarity in the context of the Peloponnesian War, see Peter J. Fliess, C. Bradford Welles, Thucydides and the Politics of Bipolarity (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1966).

Share of global GDP (MER)

The U.S. commanded an outsized share of the global economy after World War II, but in recent years, China’s rise has moved its economy closer to parity.

One of the most important causes of hegemonic wars in the wake of power transitions is the “security dilemma,” the ubiquitous yet unintended dynamic in which the efforts one state takes to ensure its security invariably undermine that of other states.33John H. Herz, “Idealist Internationalism and the Security Dilemma,” World Politics 2, no. 2 (January 1950): 157–180; Robert Jervis, “Cooperation Under the Security Dilemma,” World Politics 30, no. 2 (January 1978): 167–214. While in an anarchical international system, the security dilemma can never be eliminated, it can be mitigated in many cases by the policies states embrace. Thucydides thinks the Peloponnesian War results from the breakdown of the balance of power between Athens and Sparta and he applauds Pericles’ efforts to try to reestablish it through restraint.

How to balance the dragon

Not only is a balance of power strategy—like offshore balancing or restraint—less likely to exacerbate the security dilemma, it is eminently more feasible and will better serve American security and prosperity interests. Both offshore balancing and restraint are based upon balance of power theories of international relations. Where they differ is on the specific values of the variables in the strategic equation (does current technology favor offense or defense, the specific geography involved, the strength of the adversary, and the capabilities of the other members of the balancing coalition?) that would lead us to think the United States, or any other hegemon, needs to take a more or less active role in balancing or whether they can rely more on the efforts of the other states in its coalition.34On the former, see John J. Mearsheimer and Stephen M. Walt, “The Case for Offshore Balancing: A Superior U.S. Grand Strategy,” Foreign Affairs 95, no. 4 (July/August 2016), https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2016-06-13/case-offshore-balancing; Benjamin Schwarz and Christopher Layne, “A New Grand Strategy,” Atlantic, January 2002, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2002/01/a-new-grand-strategy/376471/; and Christopher Layne, “From Preponderance to Offshore Balancing: America’s Future Grand Strategy,” International Security 22, no. 1 (Summer 1997): 86–124; on the latter, see Eugene Gholz, Daryl G. Press, and Harvey M. Sapolsky, “Come Home, America: The Strategy of Restraint in the Face of Temptation,” International Security 21, no. 4 (Spring, 1997): 5–48.

As Thucydides’ history of the Peloponnesian War suggests, a balance of power approach by the United States in its contemporary rivalry with China will be more effective and less destabilizing. The key reason it will do so is it builds upon a number of well-established facts about how international politics operates, which we have known for more than 2,500 years.35A Thucydidean approach shares some superficial similarities with the bargaining approached offered in Charles L. Glaser, “A U.S.-China Grand Bargain? The Hard Choice Between Military Competition and Accommodation,” International Security 39, no. 4 (Spring 2015): 49–90, but its logic is much closer to the tacit spheres of influence approach of James Kurth, “America’s Grand Strategy: A Pattern of History,” National Interest, no. 43 (Spring 1996): 13–14 and 18–19. First, in most cases, states balance against threats, rather than bandwagoning–throwing their lot in with a stronger state in hopes that fealty rather than military capability will preserve their security.36Most balancing involves internal build-ups and imitation of the military practices of the leading powers. See Stephen M. Walt, The Origins of Alliances (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1987); Joseph M. Parent and Sebastian Rosato, “Balancing in Neorealism,” International Security 40, no. 2 (Fall 2015): 51–86. As China grows more powerful and assertive, states closest to it are feeling a greater sense of peril. Their response will be to seek ways to mitigate that threat by counterbalancing it, particularly in concert with the United States. A less forward and assertive U.S. posture will not only mitigate the security dilemma with China but also dampen common pathologies of balancing such as buck-passing by allies to the larger power and otherwise under-providing for their own security. The common problem behind both is what economists call “moral hazard,” or the propensity of actors to behave recklessly if another is insuring them against its consequences.37On these problems, see Thomas J. Christensen and Jack Snyder, “Chain Gangs and Passed Bucks: Predicting Alliance Patterns in Multipolarity,” International Organization 44, no. 2 (Spring 1990): 137–168; Mancur Olson, Jr. and Richard Zeckhauser, “An Economic Theory of Alliances,” The Review of Economics and Statistics 48, no. 3 (August 1966): 266–279; on the moral hazard problem in international relations, see Alan Kuperman, “The Moral Hazard of Humanitarian Intervention: Lessons from the Balkans,” International Studies Quarterly 52, no. 1 (March 2008): 49–80.

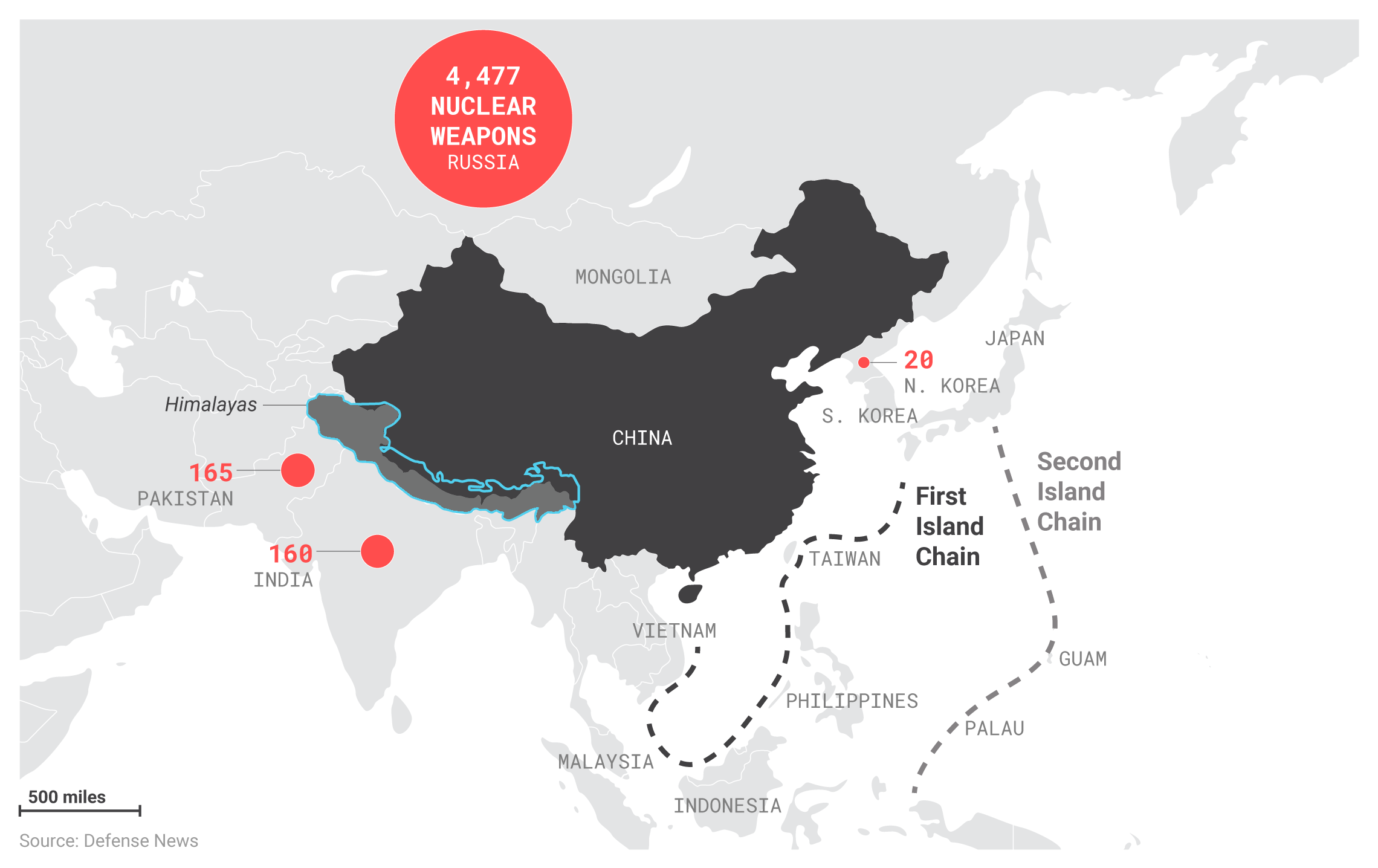

Geographical constraints on China’s maritime power

To China’s east, the first and second island chains, formed by the various islands of the East and South China Seas, create natural bottlenecks and hamper China’s ability to project power across the Pacific. Likewise, the Himalayas, combined with the nuclear capabilities of China’s neighbors, impacts China’s reach into South Asia.

Second, geography matters. While power degrades as a function of distance it also is diluted by dense forests, high mountain ranges, and especially wide bodies of water.38Kenneth Boulding, Conflict and Defense: A General Theory (New York: Harper, 1962), 262; John J. Mearsheimer, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics (New York: W.W. Norton, 2001), 114–128. The U.S.-China rivalry, in contrast to the Cold War with the Soviet Union, will be waged across wide moats rather than contiguous borders, so it is even less likely to deteriorate into hegemonic war. Taiwan, for example, is further from mainland China than Great Britain was from Nazi-held Europe and about the same distance Cuba was from Cold War Florida. Despite these relatively short distances, neither was ever successfully invaded.

Third, it is true the United States opened a considerable gap in nuclear capability between itself and other major nuclear powers, such as Russia and especially China, that leads some to believe that the United States could fight and win a nuclear war, especially with the latter.39Keir A. Lieber and Daryl G. Press, “The New Era of Counterforce: Technological Change and the Future of Nuclear Deterrence,” International Security 41, no. 4 (Spring 2017): 9–49; Lyle Goldstein, “Raising the Minimum: Explaining China’s Nuclear Buildup,” Defense Priorities, April 5, 2022, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/raising-the-minimum-explaining-chinas-nuclear-buildup. But given that both the United States and China have substantial nuclear capabilities, the Nuclear Revolution should further reduce the chances of major war between them, in much the same way it kept the Cold War from turning hot.40John Lewis Gaddis, “The Long Peace: Elements of Stability in the Postwar International System,” International Security 10, No. 4 (Spring, 1986): 120–123. Indeed, even when the United States had an even greater nuclear advantage over the Soviet Union than it has over China today, and in the face of multiple serious crises, it never executed a preemptive nuclear first strike.41On the Nuclear Revolution see Robert Jervis, The Meaning of the Nuclear Revolution (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1989). On the stability of deterrence with even a very small number of nuclear weapons, see Kenneth N. Waltz, “More May Be Better” in Scott D. Sagan and Kenneth N. Waltz, The Spread of Nuclear Weapons: A Debate Renewed (New York: W.W. Norton, 2003), 17–29.

Fourth, states’ strategic choices matter, particularly in how they choose to arm themselves, and that will continue to be true in the twenty-first century. Many fret that recent Chinese investments in anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) technologies make it harder for the United States to continue to project power close to China. However, these same technologies could also bolster America’s beleaguered allies in the region.42Eugene Gholz, Benjamin Friedman, and Enea Gjoza, “Defensive Defense: A Better Way to Protect U.S. Allies in Asia,” The Washington Quarterly 42, no. 4 (2019): 171–189, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/0163660X.2019.1693103; Michael Beckley, “The Emerging Military Balance in East Asia: How China’s Neighbors Can Check Chinese Naval Expansion,” International Security 42, no. 2 (Fall 2017): 78–119, https://direct.mit.edu/isec/article/42/2/78/12177/The-Emerging-Military-Balance-in-East-Asia-How. To defeat them militarily, China will have to project power across water, always a dicey proposition, but one made even harder now if U.S. allies in the region invest in their own A2/AD technologies.

Finally, and most important, we should keep in mind that despite the power transition that is taking place, the United States still wields considerable actual and latent power compared to China.43Michael Beckley in “Debating China’s Rise and Decline,” 172–181 also makes a convincing case the United States is still ahead of China in some important measures of power. Even if it is challenged in the East Asian region, the United States nonetheless retains what Barry Posen calls “the command of the commons” globally.44Barry R. Posen, “Command of the Commons: The Military Foundation of U.S. Hegemony,” International Security 28, no. 1 (Summer, 2003): 5–46.

Conclusion

In sum, Thucydides’ fundamental lessons for the contemporary United States in its rivalry with China is that democratic Athens erred when it sought to maintain its primacy by expanding its empire during the Peloponnesian War; today, we do not need to preserve a position of primacy in East Asia but can instead rest content with a modest and attainable goal of maintaining a balance of power. Therefore, the best grand strategy for the contemporary United States I believe, and the Thucydidean approach I know, favors the more restrained balance of power approach. Grand strategies based upon balance of power, like restraint or offshore balancing, will prove more feasible and successful than those based upon some form of power maximization, such as conservative internationalism, primacy, deep engagement, or liberal internationalism, for the United States to manage its rivalry with China in this century without blundering into the “Thucydides trap.” War is a choice.

Endnotes

- 1Robert B. Strassler, ed., The Landmark Thucydides: A Comprehensive Guide to the Peloponnesian War (New York: The Free Press, 1996), 1.22.4.

- 2In addition to Plutarch’s Lives and Hobbes’ translation of Thucydides, see Carl J. Richard, The Founders and the Classics: Greece, Rome, and the American Enlightenment (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1994) and Thomas E. Ricks, First Principles: What America’s Founders Learned From the Greeks and Romans and How That Shaped Our Country (New York: Harper, 2020); Charles N. Edel, Nation Builder: John Quincy Adams and the Grand Strategy of the Republic (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2014), 18–22; Garry Wills, Lincoln at Gettysburg: The Words That Remade America (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1992); and Hans Delbrücke, Die Strategie des Perikles erläutert durch die strategie Friedrichs des Grossen. Mit einem anhang über Thueydides und Kleon (Berlin: G. Reimer, 1890).

- 3“Speech at Princeton, February 22, 1947” at https://www.marshallfoundation.org/articles-and-features/marshall-plan-princeton-speech/. Also see State Department Official Louis J. Halle, Civilization and Foreign Policy: An Inquiry for Americans (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1975 [1952]), Appendix: “A Message from Thucydides.”

- 4Making this argument are Danielle S. Allen, “The Aims of Education Address 2001,” University of Chicago, September 20, 2001, https://college.uchicago.edu/student-life/aims-education-address-2001-danielle-s-allen; George Bornstein, “Reading Thucydides in America Today,” Sewanee Review 123, no. 4 (Fall 2015): 661–667.

- 5Graham Allison, “The Thucydides Trap: Are the U.S. and China Headed for War?” Atlantic, September 24, 2015, https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2015/09/united-states-china-war-thucydides-trap/406756/; Graham Allison, Destined for War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides’ Trap? (Boston, MA: Mariner Books, 2018).

- 6Robert Gilpin, “The Theory of Hegemonic War,” The Journal of Interdisciplinary History 18, no. 4 [The Origin and Prevention of Major Wars] (Spring 1988): 591–613; A.F.K. Organski and Jacek Kugler, The War Ledger (Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press, 1980), 19–22. Also see Mark Kauppi, “Thucydides: Character and Capabilities,” Security Studies 5, no. 2 (Winter 1995): 142; William C. Wohlforth, “Gilpinian Realism and International Relations,” International Relations 25, no. 4 (December 2011): 499–511. Richard Ned Lebow, “Thucydides, Power Transition Theory, and the Causes of War” in Hegemonic Rivalry, eds. Richard Ned Lebow and Barry Strauss (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1991), 125–165 rejects the PTT account of the origins of the Peloponnesian War on the grounds that Athens’ power was not in fact growing.

- 7Allison, Destined for War, 42.

- 8Also see Robert B. Zoellick, “U.S., China, and Thucydides,” National Interest, no. 126 (July/August 2013): 22–30. I find Joshua Itzkowitz Shifrinson’s part of his correspondence with Michael Beckley in “Debating China’s Rise and Decline,” International Security 37, no. 3 (Winter 2012/13): 172–177 makes a compelling case that China is indeed a “rising” power and closing the gap with the United States in some important measures of power.

- 9David C. Kang, “Hierarchy and Legitimacy in International Systems: The Tribute System in Early Modern Asia,” Security Studies 19, no. 4 (2010): 591–622.

- 10Jonathan Kirshner, “Handle Him With Care: The Importance of Getting Thucydides Right,” Security Studies 28, no. 1 (January–March 2019): 12.

- 11“Speech by H.E. Xi Jinping,” Welcoming Dinner Hosted by Local Governments and Friendly Organizations in the United States, September 24, 2015, https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/topics_665678/2015zt/xjpdmgjxgsfwbcxlhgcl70znxlfh/201510/t20151013_705321.html.

- 12Mo Shengkai and Chen Yue, “The U.S.-China ‘Thucydides Trap’: A View From Beijing,” National Interest, July 10, 2016, https://nationalinterest.org/print/feature/the-us-china-thucydides-trap-view-beijing-16903.

- 13Emma V. Broomfield, “Perceptions of Danger: The China Threat Theory,” Journal of Contemporary China 12, no. 35 (August 2010): 265–284.

- 14John Mecklin, “Interview with Graham Allison: Are the United States and China charging into Thucydides’ trap?” Bulletin of Atomic Scientists, March 10, 2022, https://thebulletin.org/premium/2022-03/interview-with-graham-allison-are-the-united-states-and-china-charging-into-thucydidess-trap/.

- 15Allison, Destined for War, 187–213 and 287.

- 16Mecklin, “Interview with Graham Allison.”

- 17Allison, Destined for War, 30 and 39–40.

- 18Allison, Destined for War, 42.

- 19Landmark Thucydides, 123.6.; Allison, Destined for War, xiv.

- 20The Jeremy Mynott translation of Thucydides, The War of the Peloponnesians and the Athenians (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 1.23.6.

- 21Arthur M. Eckstein, “Thucydides, the Outbreak of the Peloponnesian War, and the Foundation of International Systems Theory,” The International History Review 25, no. 4 (December 2003): 757–774.

- 22Arlene W. Saxonhouse, “Kinēsis, Navies, and the Power Trap in Thucydides” in Ryan K. Balot, Sara Forsdyke, and Edith Foster, eds., The Oxford Handbook of Thucydides (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017), 351.

- 23Landmark Thucydides, 2.65.6-7 and 10–11.

- 24Landmark Thucydides, 5.89.1.

- 25Compare Allison, Destined for War, 235–238 with footnote 38.

- 26Richard Bernstein and Ross H. Munro, “The Coming Conflict With America,” Foreign Affairs 76, no. 2 (March/April 1997): 18-32 make the baldest case for this power maximalist approach to China. Aaron L. Friedberg, A Contest for Supremacy: China, America, and the Struggle for Mastery in Asia (New York: W.W. Norton 2011), 274–284 urges the United States to preserve a “favorable balance of power,” by which he clearly means U.S. hegemony. Predicting that the United States will try to maintain its power advantage over China and endorsing “containment” as a means of doing so is John J. Mearsheimer, “Can China Rise Peacefully?” National Interest, October 25, 2014, https://nationalinterest.org/commentary/can-china-rise-peacefully-10204. Finally, arguing that this will be easy because the U.S. is so far ahead of China are Michael Beckley, “China’s Century? Why America’s Edge Will Endure,” International Security 36, no. 23 (Winter 2011/12): 41–78 and Stephen G. Brooks and William C. Wohlforth, “The Once and Future Superpower: Why China Won’t Overtake the United States,” Foreign Affairs 95, no. 3 (May/June 2016): 91–104.

- 27The Hegemonic Stability case for continuing U.S. leadership was expanded and applied to the People’s Republic of China in Zalmay M. Khalilizad, Abram N. Shulsky, Daniel L. Byman, Roger Cliff, David T. Orletsky, David Shlapak, and Ashley Tellis, The United States and a Rising China: Strategic and Military Implications (Santa Monica, CA: The RAND Corporation, 1999), 69–75. For an illustration of how easily Liberals can embrace this basic logic, see G. John Ikenberry, “The Rise of China and the Future of the West: Can the Liberal System Survive?” Foreign Affairs 87, no. 1 (January/February 2008): 23–37.

- 28Paul C. Avey, Jonathan N. Markowitz, and Robert Reardon, “Disentangling Grand Strategy: International Relations Theory and U.S. Grand Strategy,” Texas National Security Review 2, no. 1 (November 2018): 30. Table 1 nicely summarize the basic theoretical fault-line undergirding post-Cold War grand strategy debates as being between proponents of power maximization as opposed to power balancers.

- 29In balance of power theory, the balance of power is both a prediction about what states will seek to secure themselves and also a normative objective, a way to keep the peace by matching strength with strength, rather than seeking dominance, an imbalance likely to prove dangerous due to fear on the weaker side and potentially destabilizing security dilemmas. See Barry R. Posen, The Sources of Military Doctrine: France, Britain, and Germany between the World Wars (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1984), 59–74.

- 30For a similar reading, see Patrick Porter, “Thucydides Was a Realist,” Engelsberg Ideas, April 1, 2022, https://engelsbergideas.com/essays/in-defence-of-thucydides-the-realist/.

- 31Christopher Layne, “This Time It’s Real: The End of Unipolarity and the ‘Pax Americana,’” International Studies Quarterly 56, no. 1 (March 2012): 203–213.

- 32The classic articulation of this argument remains Kenneth N. Waltz, “The Stability of a Bipolar World,” Daedalus 93, no. 3 (Summer 1964): 881–909. I thank William Ruger for this observation. For a less sanguine view of bipolarity in the context of the Peloponnesian War, see Peter J. Fliess, C. Bradford Welles, Thucydides and the Politics of Bipolarity (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1966).

- 33John H. Herz, “Idealist Internationalism and the Security Dilemma,” World Politics 2, no. 2 (January 1950): 157–180; Robert Jervis, “Cooperation Under the Security Dilemma,” World Politics 30, no. 2 (January 1978): 167–214.

- 34On the former, see John J. Mearsheimer and Stephen M. Walt, “The Case for Offshore Balancing: A Superior U.S. Grand Strategy,” Foreign Affairs 95, no. 4 (July/August 2016), https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2016-06-13/case-offshore-balancing; Benjamin Schwarz and Christopher Layne, “A New Grand Strategy,” Atlantic, January 2002, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2002/01/a-new-grand-strategy/376471/; and Christopher Layne, “From Preponderance to Offshore Balancing: America’s Future Grand Strategy,” International Security 22, no. 1 (Summer 1997): 86–124; on the latter, see Eugene Gholz, Daryl G. Press, and Harvey M. Sapolsky, “Come Home, America: The Strategy of Restraint in the Face of Temptation,” International Security 21, no. 4 (Spring, 1997): 5–48.

- 35A Thucydidean approach shares some superficial similarities with the bargaining approached offered in Charles L. Glaser, “A U.S.-China Grand Bargain? The Hard Choice Between Military Competition and Accommodation,” International Security 39, no. 4 (Spring 2015): 49–90, but its logic is much closer to the tacit spheres of influence approach of James Kurth, “America’s Grand Strategy: A Pattern of History,” National Interest, no. 43 (Spring 1996): 13–14 and 18–19.

- 36Most balancing involves internal build-ups and imitation of the military practices of the leading powers. See Stephen M. Walt, The Origins of Alliances (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1987); Joseph M. Parent and Sebastian Rosato, “Balancing in Neorealism,” International Security 40, no. 2 (Fall 2015): 51–86.

- 37On these problems, see Thomas J. Christensen and Jack Snyder, “Chain Gangs and Passed Bucks: Predicting Alliance Patterns in Multipolarity,” International Organization 44, no. 2 (Spring 1990): 137–168; Mancur Olson, Jr. and Richard Zeckhauser, “An Economic Theory of Alliances,” The Review of Economics and Statistics 48, no. 3 (August 1966): 266–279; on the moral hazard problem in international relations, see Alan Kuperman, “The Moral Hazard of Humanitarian Intervention: Lessons from the Balkans,” International Studies Quarterly 52, no. 1 (March 2008): 49–80.

- 38Kenneth Boulding, Conflict and Defense: A General Theory (New York: Harper, 1962), 262; John J. Mearsheimer, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics (New York: W.W. Norton, 2001), 114–128.

- 39Keir A. Lieber and Daryl G. Press, “The New Era of Counterforce: Technological Change and the Future of Nuclear Deterrence,” International Security 41, no. 4 (Spring 2017): 9–49; Lyle Goldstein, “Raising the Minimum: Explaining China’s Nuclear Buildup,” Defense Priorities, April 5, 2022, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/raising-the-minimum-explaining-chinas-nuclear-buildup.

- 40John Lewis Gaddis, “The Long Peace: Elements of Stability in the Postwar International System,” International Security 10, No. 4 (Spring, 1986): 120–123.

- 41On the Nuclear Revolution see Robert Jervis, The Meaning of the Nuclear Revolution (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1989). On the stability of deterrence with even a very small number of nuclear weapons, see Kenneth N. Waltz, “More May Be Better” in Scott D. Sagan and Kenneth N. Waltz, The Spread of Nuclear Weapons: A Debate Renewed (New York: W.W. Norton, 2003), 17–29.

- 42Eugene Gholz, Benjamin Friedman, and Enea Gjoza, “Defensive Defense: A Better Way to Protect U.S. Allies in Asia,” The Washington Quarterly 42, no. 4 (2019): 171–189, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/0163660X.2019.1693103; Michael Beckley, “The Emerging Military Balance in East Asia: How China’s Neighbors Can Check Chinese Naval Expansion,” International Security 42, no. 2 (Fall 2017): 78–119, https://direct.mit.edu/isec/article/42/2/78/12177/The-Emerging-Military-Balance-in-East-Asia-How.

- 43Michael Beckley in “Debating China’s Rise and Decline,” 172–181 also makes a convincing case the United States is still ahead of China in some important measures of power.

- 44Barry R. Posen, “Command of the Commons: The Military Foundation of U.S. Hegemony,” International Security 28, no. 1 (Summer, 2003): 5–46.

More on Asia

By John Mueller

April 10, 2025

Featuring Jennifer Kavanagh

April 2, 2025

Featuring Lyle Goldstein

April 1, 2025

Featuring Jennifer Kavanagh

March 27, 2025