Key points

Over the past several decades, the United States has made the advance of democracy its great purpose in foreign policy. The Biden administration’s rhetoric about a global struggle between autocracy and democracy is the old habit in new form.

U.S. leaders market this goal as consonant with the U.S. liberal tradition, but it in fact offends the nation’s founding ethos, especially in relegating state sovereignty and national independence to secondary status. In the older teaching, accepted even by liberal internationalists like President Woodrow Wilson and President Franklin Roosevelt, free institutions were to expand by example, not by force.

After the Cold War, U.S. efforts to push states into becoming democracies by instruction, war, and sanctions have been an abject failure, in large part because they offended against the principle of national independence.

Defining U.S. efforts today as the defense of democracy obscures vital problems in the U.S. alliance system, including its expansionist tendencies, its unfair sharing of burdens, and the risks it poses of a major war that would be detrimental to U.S. security.

The U.S. should reject the revolutionary policy of regime change and return to the respect for national independence once embedded in the U.S. diplomatic tradition. Overturning autocratic governments is an aim that is antithetical to peace, the most favorable environment for the growth of liberal democracy.

Wither history

Francis Fukuyama’s 1989 essay on “The End of History?” had as its provocative tease the thesis that humankind had reached the endpoint of its ideological evolution. What went before—what Edward Gibbon called a “register of the crimes, follies, and misfortunes of mankind”—had culminated after all those years in the institutions of the modern liberal democratic state. Communism was busted. In 1989, no other model looked like much of a rival, save Islam, whose appeal was inherently particularistic. None could make a claim to universality; none, that is, except the democratic institutions practically invented in the United States.1

For most of the nineteenth century, the United States was a rather lonely outpost among the world’s few democracies, which generally in that day didn’t call themselves that. By the end of the 1980s, it looked like democracy was running the table. Its charms were irresistible. Political scientist Samuel P. Huntington called it “the third wave” of democratic advance.2 Begun in the mid-1970s, the third wave proved stronger than the previous two, sweeping through South America and East Asia before it went on to dispose of Communism and Apartheid. Most remarkably, the democratic conquest was achieved peacefully, conducted to victory by “people power.” To many, the only logical stopping point was the triumph of the liberal democratic idea across the entire planet.

In the subsequent 30-plus years, Fukuyama’s striking argument—History Has Ended!—has been misinterpreted and masticated countless times in universities all over the world, chewed up, spit out, rejected. The academics, then, didn’t like it, but America’s political nation did. Fukuyama’s general idea won great favor in Washington. Indeed, this political triumph didn’t need Fukuyama’s essay as a spark; the fire was already burning. Four months before his essay appeared, President George H.W. Bush had stated about 98 percent of the Fukuyama thesis (leaving out the continental philosophy) in his inaugural address:

We know what works: Freedom works. We know what’s right: Freedom is right. We know how to secure a more just and prosperous life for man on Earth: through free markets, free speech, free elections, and the exercise of free will unhampered by the state. For the first time in this century, for the first time in perhaps all history, man does not have to invent a system by which to live. We don’t have to talk late into the night about which form of government is better. We don’t have to wrest justice from the kings. We only have to summon it from within ourselves. We must act on what we know.3

In one respect, President Bush was simply reiterating those features of the American way of life that, in 1989, made it attractive for other peoples as an example to emulate, but it could also be read as a call to launch a crusade on behalf of freedom and democracy. President Bush was suspected by the neoconservatives of not buying into the implied program of global reconstruction, and in fact the United States wavered between the roles of exemplar and crusader in the 1990s. In 2001, all that changed. The administration of his son, President George W. Bush, showed no such reticence in embracing the role of crusader for freedom and democracy, in which America would emphatically enforce its will in conviction of the right. The elder President Bush, it seems fair to say, recoiled from the full implications of what he had said. Not so his son.

Four doctrines for democracy: Reagan, Clinton, Bush, and Biden

The defense and advance of democracy has been the great theme of U.S. statecraft over the last 40 years. It took various forms. The most important landmarks in the past were the Reagan Doctrine of the 1980s, the Clinton Doctrine of the 1990s, and the Bush Doctrine of the 2000s.

The Reagan Doctrine was christened as such by columnist Charles Krauthammer in 1985. It meant U.S. support for insurgencies against communist regimes in Nicaragua, Afghanistan, Angola, and Cambodia. Its most important exposition was a February 1985 speech by Secretary of State George Shultz, who held it vital to stand with “the forces of democracy around the world.”4 To abandon young Afghans, Nicaraguans, or Cambodians to oppression “would be a shameful betrayal—a betrayal not only of brave men and women but of our highest ideals.”5 The new policy represented a departure from the language that President Reagan had previously used. “The basis of a free and principled foreign policy,” he said in accepting the Republican nomination in 1980, “is one that takes the world as it is, and seeks to change it by leadership and example; not by harangue, harassment or wishful thinking.”6

Despite an initially cautionary stance, President Reagan came to see arms transfers to insurgents as a force of change and liberation. He insisted his policy would advance freedom and democracy, but it required association with unsavory characters. Angolan insurgent Jonas Savimbi, anointed in the 1980s as a freedom fighter by President Reagan and seen as such by numerous newspapers and think tanks in the United States, was later deemed a dangerous bandit by U.S. diplomats in the 1990s. The right-wing forces supported by the United States on Cambodia’s border, in opposition to the new regime imposed on Cambodia by North Vietnam, were joined on their left flank by the surviving remnants of Cambodia’s Khmer Rouge, responsible for Cambodia’s genocide in the late 1970s. However, these and other cautionary tales from the 1980s were swept aside in the euphoria accompanying the downfall of communism in Europe.

The Clinton Doctrine spoke of enlarging the community of liberal and market states; it launched the campaign to expand NATO into Eastern Europe. While President Clinton intervened in Haiti to “restore democracy” in 1994, his largest effort lay in the reconstruction of European order under the auspices of NATO. This meant abandoning the pledge to Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev that NATO would expand “not one inch” to the East.7 NATO, it was said in the mid-1990s, must go “out of area” or “out of business,” suggesting security for its members was no longer a sufficient objective of the alliance. Russia, ravaged by 70 years of Communist rule, was in no position to resist. In time the objective would compromise the arms control treaties that initially defined the post-Cold War security order in Europe.

The Bush Doctrine of 2002 was the most grandiose of all. Its guiding inspiration was to press on all fronts for the victory of freedom and democracy. President Bush eloquently summarized the charge in his second inaugural address. His premises were twofold: “The survival of liberty in our land increasingly depends on the success of liberty in other lands. The best hope for peace in our world is the expansion of freedom in all the world.” His conclusion was that “it is the policy of the United States to seek and support the growth of democratic movements and institutions in every nation and culture, with the ultimate goal of ending tyranny in our world.”

The history of NATO EXPANSION

After the Cold War, NATO expanded eastward in successive waves, breaking pledges made to Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev in 1990. U.S. diplomat George Kennan warned in 1997 that expansion to Russia’s borders, intended to consolidate democracy in Europe’s east, would be a fateful error. He predicted that it would inflame the nationalistic and anti-Western tendencies in Russian opinion, hinder Russia’s democratization, and impel Russian foreign policy in hostile directions.

The United States under President Biden portrays its fundamental purpose in the world as defending Democracy against Autocracy. That theme was also characteristic of the Reagan, Clinton, and Bush doctrines. As this is a central aim of U.S. foreign policy, the entirety of the national security state, at more than $1 trillion a year, is arguably pledged to this end. For this reason, what is counted as a line item in the federal budget for “democracy building,” at some $2 billion a year, is insignificant in comparison with this larger purpose.

Officials do not distinguish in their rhetoric between “defending” and “advancing” democracy, but in budgetary terms we can distinguish between expenditures for protecting America’s allies in Europe and Asia and the “regime change” wars of the last generation. In fundamental respects, both are tokens of America’s self-declared devotion to democracy, but they raise separate issues. “Defending” is different from “advancing.” While America’s treaties of mutual support with democratic allies have raised issues of equity, expense, and security, no one can deny the United States has a right to form alliances with fellow republics or democracies. The right to overturn governments, which the United States sought to do on many occasions in the last 30 years, raises an entirely different set of issues. Remarkably, almost imperceptibly, it came to be taken for granted that the United States enjoyed a right to engage in “regime change” through coercive means. This was not the traditional American diplomatic posture.

This essay seeks to make two large points. First, the doctrine of ending tyranny throughout the world, or of advancing democracy coercively, makes an appeal to the Founding Fathers and to what “we’ve always believed,” but in fact going abroad in search of monsters to destroy had nothing to do with the philosophy of international affairs embraced by the Founders and their followers in the American diplomatic tradition. They saw such doctrines of forcible revolution as offensive to the principles of natural right and independence on which they had built the United States. Second, these coercive efforts have been an abject failure. The two points, one may suggest, are related. By offending against the principle of national independence, the United States committed itself to an enterprise doomed to frustration.

Old teaching vs. new teaching

Founding injunctions

Thomas Jefferson wrote in the Declaration of Independence that life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness were at the core of the natural rights of man. Did nations enjoy the same rights? It is the assumption of contemporary U.S. statecraft, which takes as its creed the advance of democracy, that they do not legitimately have the choice of their own institutions, or rather that this choice must logically take the form of democracy if it is to have any meaning. It has been America’s mission in the twenty-first century to overthrow tyrants and to bring democracy to people suffering under tyranny. That was not how Jefferson conceived of America’s mission. He thought that other nations “had the right, and we none, to choose for themselves.”8

On this point Alexander Hamilton was entirely in accord with his great adversary. Dictating to other nations the form of government they must have, as Hamilton put it, was contrary “to the general rights of Nations, to the true principles of liberty, [and] to the freedom of opinion of mankind.”9 Jefferson reproved the French on the same ground but thought the alliance of monarchies directed against France was more guilty than France on that score. Hamilton and Jefferson differed profoundly on whether France or the confederacy of kings was most responsible for the European conflagration, that is, who was most guilty of violating the norm of non-intervention. But they both appealed to the same norm.

In embracing this view, neither of these men was plowing new ground. This was also the teaching of the law of nations, and especially of its most recent refined statement by Emer de Vattel in his treatise, The Law of Nations: Principles of the Law of Nature Applied to the Conduct and Affairs of Nations and Sovereigns (1758), a book widely approved in the United States.10 The law of nations, and then of international law, made the domestic government and constitution of every nation a matter of its own will. The law of nations sought rules of the road that did not bring that contested question into play.

History, to be sure, often brought that question very much into play, from the religiously motivated interventions of the seventeenth century to the wars of the French Revolution to the humanitarian interventions of the nineteenth century.11 The history of European diplomacy and war, it might be said, is the history of intervention. The history of international law, by contrast, is the attempt to restrict that tendency. Extended controversies existed over when military intervention might be legitimate, but international law rejected the idea that international society could be constructed on the basis of a universal concordance among the various types of domestic regimes. To do so would create enormous fractures within it. In the old teaching, observance of the rule of non-intervention in the internal affairs of other states was seen as indispensable to the preservation of peace. These ideas were reiterated constantly by American diplomatists in the nineteenth century, of whom the greatest figures were John Quincy Adams, Daniel Webster, and William Seward.12

Woodrow Wilson and his legacy

Was their teaching overthrown by liberal internationalism in the twentieth century? The belief that it was is often asserted. President Woodrow Wilson, especially, plays the starring role in this ideological transformation from exemplar to crusader. And President Wilson was a crusader—a big change—but more for collective security than democracy. President Wilson wanted to make the world safe for democracy, not shove democracy down everybody’s throat. The League of Nations he wanted desperately for America to join, but which it did not join, was dedicated to the prevention of aggression, not the spread of democracy, though it required for its efficacy cooperation among the oldest and newest democracies in Europe.13

What makes President Wilson’s outlook difficult to interpret is that his most prized ideal, self-determination, was subject to multiple meanings. The biggest difficulty was identifying “the self” that would be doing the determining. Was it the nation, the state, the volk, or a community of citizens? One scholar identified three meanings: external self-determination, or freedom from alien rule; internal self-determination, the right of a people to choose its form of government; and democracy, which embraced not only the will of the people or nation, but also did so in constitutional forms.14

President Wilson placed greater weight on external self-determination than either internal self-determination or democracy. His idea for the League of Nations centered on the guarantee of the political independence of states, a political independence that was to be “absolute in domestic matters, limited in external affairs only by the rights of other nations.”15 He believed in democracy as the best way forward, but also understood and accepted that every people had the choice of their own institutions. “If they don’t want democracy,” he said of the new peoples emerging from the war, “it’s none of my business.”16

President Wilson expressed this view in relation to many different conflicts, especially the Mexican and Russian revolutions. The people on the ground had to figure it out, he believed, even if they had to go through hell to get there. Foreigners had neither the right nor the wisdom to find that resolution for them. In the case of neither Mexico nor Russia did the U.S. government exactly follow President Wilson’s prescriptions, and President Wilson himself changed his mind on some occasions. He waded thickly into Mexico in 1913 and 1914, then turned away in disgust. Nevertheless, this view of national right strongly figured in his philosophy of international relations. On this point he simply restated the traditional American consensus aiming not at a fully democratic world but a world that was safe for democracy and political diversity.

President Wilson may fairly be charged with ignoring the right to national self-determination of non-European peoples, who immediately recognized—from Korea, Vietnam, and China to India, Syria, and Egypt—the relevance of President Wilson’s principle to their own situation. That fact, however, does not diminish the intrinsic merit of the principle that President Wilson set forth.17

The right of national independence and the prevention of aggression were also central to President Franklin Roosevelt’s conception of international order. “There never has been, there isn’t now and there never will be, any race on earth fit to serve as masters of their fellow men,” declared President Roosevelt. “We believe that any nationality, no matter how small, has the inherent right to its own nationhood.”18 The United Nations that President Roosevelt shepherded to its birth in 1945 contained many nondemocratic states. Its charter gave no powers in its chief policy-making institution, the U.N. Security Council, to change the governments of other states. Its purpose was to ensure international peace and security. So, too, the signatories of the North Atlantic Treaty in 1949 pledged fidelity to the principles of the U.N. Charter and emphasized “their desire to live in peace with all peoples and all governments.”19

Public aims and covert actions during the Cold War

The old teaching became battered and bruised during the Cold War. As shown in the meticulous research of Lindsey O’Rourke and other scholars, America’s Cold War record blossomed with interventions across the globe, some little and covert, some big and overt.20 The warrant for this had been given in the Truman Doctrine, offered by President Harry S. Truman in 1947. The United States, President Truman declared, “must “support free peoples who are resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities or by outside pressures.” As Walter Lippmann complained at the time, President Truman’s declaration was open-ended and could only be implemented “by recruiting, subsidizing and supporting a heterogeneous array of satellites, clients, dependents, and puppets.” The management of this ungainly coalition would require “continual and complicated intervention by the United States in the affairs of all the members of the coalition,” however much such intervention was disavowed. Meanwhile, Congress and the American people “would have to stand ready to back their judgments as to who should be nominated, who should be subsidized, who should be white-washed, who should be seen through rose-colored spectacles.”21

COUNTRIES TARGETED FOR REGIME CHANGE BY THE U.S. DURING THE COLD WAR

Although the United States put the principles of the UN Charter at the center of its foreign policy pronouncements during the Cold War, its strictures against intervention were often covertly violated by U.S. diplomats and spies during that time. The great purpose of such intervention was usually to fight communism, not build democracy.

Lippmann’s warnings proved prophetic in both parts. Intervention would occur. It would also be disavowed. In his inaugural address in 1953, President Dwight D. Eisenhower seemed to foreswear such activity: “Honoring the identity and the special heritage of each nation in the world, we shall never use our strength to try to impress upon another people our own cherished political and economic institutions.”22 In practice, his administration gave carte blanche to the CIA to meddle endlessly in the internal affairs of other governments, though in none of these cases was the result a reproduction of America’s cherished institutions.

This contrast between what was said in public and what was going on behind the scenes came out during the Vietnam Era, most notably in congressional investigations of the mid-1970s. In the minds of ordinary Americans, however, it was taken for granted that America was among the peacekeepers, not the peacebreakers. As President John F. Kennedy summarized the old consensus in 1963 in a speech at American University: “World peace, like community peace, does not require that each man love his neighbor—it requires only that they live together in mutual tolerance, submitting their disputes to a just and peaceful settlement.”23 At that time, based on Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev’s ringing call to support wars of national liberation against the colonial powers, President Kennedy put the blame on the Soviet bloc. “The Communist drive to impose their political and economic system on others is the primary cause of world tension today. For there can be no doubt that, if all nations could refrain from interfering in the self-determination of others, the peace would be much more assured.” President Kennedy’s leitmotif was not the convergence of the world’s peoples on the American form of government. It was to “make the world safe for diversity.”

As with the Eisenhower Administration, there was more there than met the eye. The CIA continued its interventionist ways under President Kennedy and his successors. But the idea of world order they put forward to the American public was not that of such intervention. They repudiated in public what they were doing in private, but hypocrisy was in this instance a tribute paid to virtue. It did bespeak the continued salience, in public opinion, of the substratum of belief and conviction underlying the old American consensus. The same understanding was reflected in the writings of strategists like Bernard Brodie. The United States, Brodie wrote in the late 1950s, “is, and has long been, a status quo power. We are uninterested in acquiring new territories or areas of influence or in accepting great hazard in order to rescue or reform those areas of the world which now have political systems radically different from our own. On the other hand, as a status quo power, we are also determined to keep what we have, including existence in a world of which half or more is friendly, or at least not sharply and perennially hostile.”24

What can we conclude from this history? The conclusion is irresistible that the quest to advance democracy that captured American statecraft after the end of the Cold War was not an authentic transmitter of the old teaching, but a perversion of it. It took a practice once hidden behind secrecy, because it crossed the norm against intervention and aggression, and dressed it up as something Americans had always believed. It changed the United States from a status quo power to a revolutionary power. It made it the imperative of American foreign policy to bend History to its will, force it into certain grooves and not others. By doing so, it made peace secondary, if not tertiary, substituting a new quest for the older teaching. Being the best example for the nations, standing for the independence of the nations, was no longer sufficient; indeed, it was craven and unworthy. The United States could only fulfill its historic mission by becoming a crusader for democracy.

That was both a great departure and a great mistake. And it didn’t work out.

Three methods for advancing democracy: Instruction, war, and economic sanctions

The American project of advancing democracy has taken three main forms over the last four decades: educational instruction, military invasion, and economic pressure. The National Endowment for Democracy (NED) was established in 1983 to teach democratic procedures and institutions to newly democratizing nations. There were the wars in Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, and Libya launched with the extension of democracy and human rights as an invariable standard-bearer, though each intervention had other justifications and motives usually attached to them. Finally, there were a vast array of economic sanctions, intended usually to punish those who violated human rights or democratic procedures. A Defense Priorities report of 2019 counted 20 countries under sanctions at that time.25

Bad teacher

The creation of the NED was the leading manifestation of America’s wish to teach democracy by instruction. Joining in these efforts were institutes directed by the Democratic and Republican parties. These efforts promised to teach democratic principles in a non-partisan manner and as such were perfectly compatible with America’s traditional mission of being an exemplar for freedom. In practice, however, the story differed. U.S. efforts often became attached to particular political movements in the countries where their efforts took place. Ukraine is the most notable example. According to Assistant Secretary of State Victoria Nuland, the United States invested $5 billion in efforts to build democracy in Ukraine as of late 2013. These efforts culminated in U.S. support for the February 2014 Revolution that overthrew democratically elected Ukrainian President Victor Yanukovych.

Top recipients of U.S. democracy promotion aid

Most of U.S. democracy promotion assistance, as categorized by the Congressional Research Service, goes though the United States Agency for International Development, the State Department, and the National Endowment for Democracy. Real expenditures are far greater, however, because the national security establishment also justifies itself in relation to this end.

Here we note a most striking anomaly. The peaceful transfer of power in the aftermath of constitutionally authorized elections is at the heart of constitutional democracy. There is no higher principle in the democratic pantheon. Yet in Ukraine, American policymakers countenanced the blatant violation of this first principle. Not surprisingly, the violation of that essential rule produced a civil war in Ukraine. While the president who was unceremoniously deposed was deeply unpopular in the west and center of Ukraine, he received 90 percent of the vote in Ukraine’s far eastern province of Crimea.

Evidently, the lesson taught by the NED was: First you make a constitution, then you break it, then you make another. The NED’s leader, Carl Gershman, saw regime change in Ukraine as a prelude to regime change in Russia,26 but in supporting the February Revolution in 2014, he and fellow democracy enthusiasts turned their back on the experience of another “young democracy,” the United States of America. From the first moments of the new government created in the Federal Convention it was understood that civil war was the alternative to the observance of the Constitution’s electoral rules. None of the statesmen who made the government and then shepherded its subsequent operation would for a moment have countenanced the idea that a transfer of power could be accomplished by assembling a crowd in the capital city for the purpose of storming the office of the president, as that would have instantly produced the dissolution of the government, not its regeneration. The alternative to the Constitution, it was said a thousand times, was disunion and war.27

Considered candidly, the observance of constitutional rules for the transfer of power is a vital bulwark that protects the United States from civil conflict today. The furor aroused, legitimately so, by the events of January 6, 2021, came from that deep recognition. Yet what could never pass muster in the United States was adopted by the U.S. government, cheered on by the U.S. commentariat, as entirely unobjectionable when applied to Ukraine in 2014. Nor was this violation of democratic rules by the February 2014 Revolution an anomaly. Ukraine after 2014 became effectively a state at war. It closed critical media outlets, pursued charges of treason against political opponents, and violated human rights with officious language laws.28

Why war can’t produce democracy

The second method adopted for the advancement of democracy and human rights, a hallmark of the George W. Bush administration especially, was military intervention. The four main cases were Afghanistan (2001), Iraq (2003), Libya (2011), and Syria (2012), the latter two undertaken by the Obama Administration. In each of these, the rhetoric of advancing democracy and protecting human rights was prominently advanced as fundamental objectives of U.S. policy at the outset. In every case, however, there emerged a striking contrast between the bright hopes announced at the beginning and the grim reality that ultimately transpired. In a word, the military operations intended to produce democracy produced anarchy.

Afghanistan

Afghanistan held democratic elections during America’s nearly 20-year occupation of the country, but the governments elected failed to achieve legitimacy with their own population. The Afghan government, U.S. officials came to realize, could not stand without expensive U.S. support, reaching in 2011 and 2012 more than $100 billion a year. When the United States withdrew in August 2021, the Afghan government disintegrated.

Iraq

Iraq under U.S. occupation wrote a new constitution, created a parliament, and held democratic elections, but it did so under circumstances of civil war. Once the Iraqi state was broken by the U.S. invasion, mortal rivalries reemerged among the Sunni, Shia, and the Kurds.29 Iraqi political parties usually came equipped with armed militias, not the typical phenomenon in a liberal democratic state. Throughout the years of the U.S. occupation (2003¬¬–2011), Iraq’s internal politics were the catspaw of external powers. They remain so today, though Iran rather than the United States has the greatest sway in Iraq’s affairs.

Libya

Libya fell into protracted civil war after the 2011 NATO operation to oust its leader Muammar Gaddafi.30 Attempts by Libyans to write a new constitution fell apart and the nation was consumed by a protracted civil war. Innumerable militias formed, based largely on tribal loyalties, with a big role played by external governments in supporting the various factions. Open-air slave markets emerged in parts of Libya, as did the formation of ISIS. The dissolution of the Libyan state opened the door to a flood of refugees, overwhelming Europe and disordering its politics.31

U.S. SPENDING ON THE WAR IN AFGHANISTAN

The United States spent billions of dollars a year on the war in Afghanistan only to have the U.S.-backed Afghan government collapse before the U.S. military could complete its withdrawal.

Syria

In Syria, the United States fell in with so-called “moderate rebels” intent on bringing down the government of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad. The overthrow of President Assad, it was hoped by the State Department, would deliver a sharp blow to Iran in its competition with Israel and usher in some more liberal alternative. In 2011, the United States called for President Assad’s removal, but President Obama was reluctant to involve U.S. forces. In 2012, however, the administration agreed, covertly, to send small arms from Libyan arsenals to Syria. In June 2013, it announced publicly it was providing military support to the opposition and it also facilitated the provision of arms behind the scenes, mostly paid for by Saudi Arabia and other Persian Gulf states, to the anti-Assad insurgency, which came to be dominated by jihadists seeking religious rule, not western-style democracy. The anarchy ensuing in 2012 and 2013 allowed ISIS to seize territory in Syria and then Iraq, prompting its great offensives in the summer of 2014.

U.S. anti-ISIS efforts came via cooperation with the Kurdish YPG (closely linked with the Turkish PKK, which has been designated as a Foreign Terrorist Organization since 1997)32 and Iranian-linked militias that worked with U.S. forces, under the watchful eye of Kurds, to drive ISIS out of northern Iraq. U.S. efforts successfully pulverized ISIS but failed to overthrow President Assad, who was saved by Russian intervention in 2015. Nothing resembling democracy and human rights was achieved on the territories where these efforts took place.

The reasons for the stark failure of building democracy through force are various. The emphasis placed by most writers is the resistance of foreign political cultures to a direct transplantation of habits, customs, procedures, and institutions formed elsewhere. Whereas Germany and Japan both had parliamentary traditions to draw on after World War II, Afghanistan, Iraq, and Libya had tenuous memories of such at best.33 While this interpretation has merit, it doesn’t reach the primordial problem, which was the condition in which external military intervention placed the inhabitants of the states newly liberated from tyranny. The military intervention effectively cast them into a state of nature, requiring them to rebuild political authority from the bottom up. That, however, is an extraordinarily difficult thing to do when rival domestic groups hold mutual suspicions of one another.

Major U.S. military interventions since the Cold War

The end of the Cold War created a new structure of power in the world that helped enable U.S. intervention. There were multiple motives for such interventions, but presidential rhetoric usually stressed the promotion of democracy and human rights as a fundamental U.S. purpose. Attempts at regime change usually followed.

The overriding obstacle to a successful democratic transition, then, is not so much differing political cultures but the near impossibility of garnering the necessary consent, in circumstances of anarchy, from the relevant political and military groupings. The same inherent difficulties would be faced if suddenly the citizens of the United States were left without their Constitution by a victorious invader, who then decreed: Make a new one in accord with the principles of democracy. Would Americans then be able to do so, like their distant forbears did in 1787? The “concurrent majorities” required by such an act seem on their face to be insuperable. After all, they called it the “Miracle at Philadelphia” for a reason. As Daniel Webster later noted in a commemorative address, establishing a united government “over distinct and widely extended communities . . . has happened once in human affairs, and but once; the event stands out as a prominent exception to all ordinary history; and unless we suppose ourselves running into the age of miracles, we may not expect its repetition.”34 Webster was perhaps too pessimistic about the requirements of constitution-making, but it follows from his observation that making a durable constitution in the middle of a civil war would require something like a miracle.

As Washington’s interventions unfolded in Afghanistan and Iraq, a cottage industry emerged acknowledging that America was doing it all wrong. The advocates of forced democratization set forth ideas for doing it right.35 Experience shows, however, that bright ideas run aground in circumstances of anarchy, which the occupying power can seek to dispel but which is created by the act of intervention itself. Foreign intervention creates nationalist or tribal resistance, like a body’s immune system repelling a virus, even unto death. The resulting anarchy creates a void into which good works vanish.

Building a democracy through war is like making a pyramid stand by inverting it. It must rest on the willingness of the participants to respect their divergences and to yield to persuasion. Its very breath is abhorrence of the gun. The conqueror, having appealed to the gun, cannot tell the locals convincingly that henceforth persuasion, rather than the gun, shall be the rule. In building a democracy, in short, a 500-pound bomb is not “fit for purpose.”36

Why economic sanctions likewise fail

The record is no better when we come to the application of economic sanctions to promote human rights and democracy. These have been “successful” in imposing pain on the recipients, but no progress in the way of promoting democracy and human rights has followed. Foreign cultures and polities display tremendous powers of resistance when put under external pressure. They can be broken by military force, but economic sanctions reveal in episode after episode an incapacity to bring the enemy to a decision. Renouncing regime change by force, as President Biden and Secretary of State Antony Blinken have done, while embracing regime change by economic sanctions, as they have also done, leaves American foreign policy in a no-man’s-land. It doesn’t achieve the objective. All it does is register America’s abstract commitment to democracy and human rights through collective punishments of ordinary people unfortunate enough to have problematic rulers.

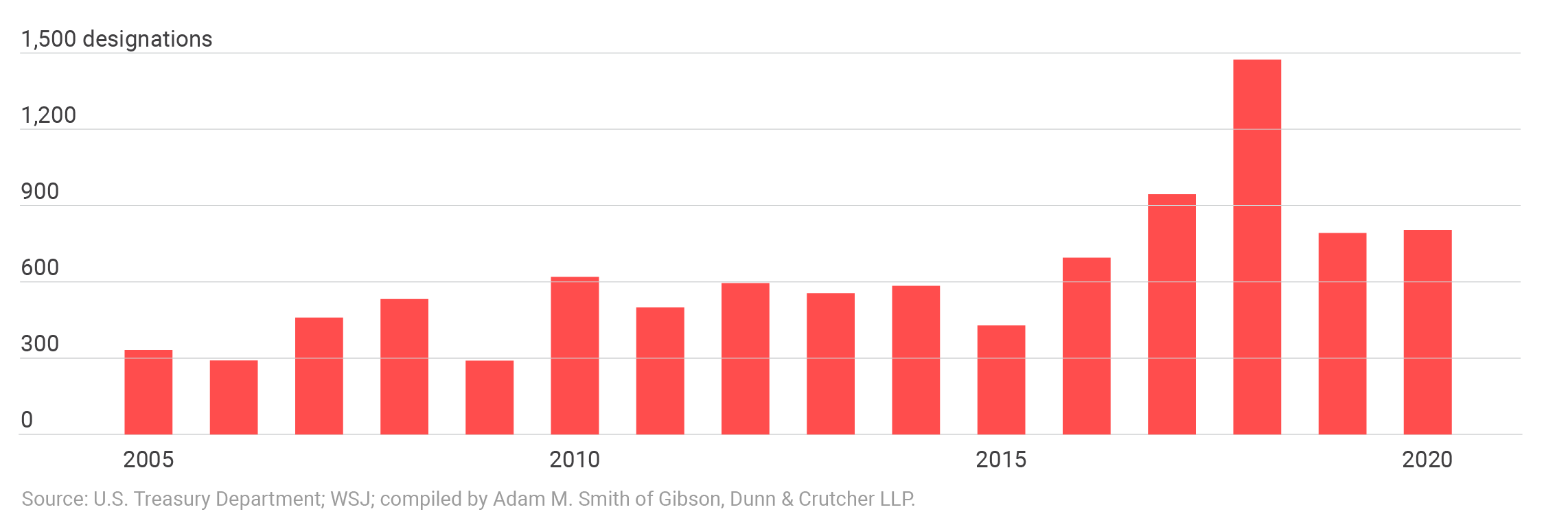

ADDITIONS TO THE U.S. SANCTIONS LIST

The number of states, entities, and individuals added to the U.S. sanctions list each year has increased, but their effectiveness in promoting democracy and human rights has not.

Economic sanctions are preeminently an instrument for the imposition of collective punishments, more so at least in some circumstances than military power. Their analogue in military strategy is the maritime blockade or, in land warfare, the siege.37 They are capable of exacting a fearsome toll, as witnessed in the 1990s by malnutrition and death among civilians, including babies, as a consequence of draconian sanctions imposed on Iraq after Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait. Advocates of sanctions, who invariably style themselves as great humanitarians, have sought to avoid such dire results by adopting “targeted” sanctions, but these are mostly symbolic and have an effect primarily propagandistic.38 The sanctions against Afghanistan, Syria, and Venezuela, to take three prominent examples today, bear harshly on the people already suffering under the rule of these illiberal regimes, with little prospect of changing the governments or any other clear measure of success. With conditions in both Afghanistan and Syria verging on widespread famine, it cannot help but injure the good name of democracy and human rights for U.S. policy to invoke these concepts while dealing death on a large scale. Former UK Foreign Secretary David Miliband, now of the International Rescue Committee, noted in January 2022 that “The current humanitarian crisis could kill far more Afghans than the past 20 years of war.”39 President Biden had promised the preceding August that withdrawing from Afghanistan would not mean the end of U.S. support for the Afghan people, but U.S. policy, Miliband noted, had done the opposite, “instead delivering isolation, economic mayhem and human misery.”40 On February 11, the Biden administration responded to Miliband’s plea not by unfreezing Afghanistan’s central bank reserves but by seizing $7 billion of them and distributing half the proceeds to 9/11 plaintiffs, in effect imposing the burden of collective responsibility on the some 20 million Afghans born since 9/11.41

A balance sheet

During the early phases of the Cold War, the covert interventions were “anti-communist” but not pro-democratic. The United States had security relationships with states run by autocrats, and so extensive were these that one commentator could complain in the late 1960s of “counterrevolutionary America.”42 Under the imprint of the Reagan Doctrine, embraced by many Democrats, that changed in vital ways, though not completely. Autocratic regimes in Latin America and East Asia received pressure to democratize, but not Arab oil producers in the Persian Gulf. Calling insurgents “freedom fighters,” moreover, did not miraculously transform them into true believers in western-style freedom and democracy. Ted Galen Carpenter, in his book Gullible Superpower, examines a dozen different countries over 40 years where the United States styled its local allies as brave fighters for freedom and democracy. As he observes, the United States could do so only by wildly distorting the facts of the situation.43

Carpenter’s case studies are the Nicaraguan contras; the Afghan Mujahideen; Jonas Savimbi’s UNITA in Angola; the Kosovo Liberation Front; Color Revolutions in Lebanon, Kyrgyzstan, and Georgia; the Iraqi National Congress led by Ahmed Chalabi; the Mujahadeen-e-Khalq (MEK), an insurgent group seeking to overthrow Iran’s government; Libyan insurrectionists of various stripes; the Ukrainian nationalists who led the February 2014 Revolution; and Syria’s “moderate rebels” (who were anything but). Gullible Superpower forms a compliment to a previous book of Carpenter’s, written with Malou Innocent, Perilous Partners: The Benefits and Pitfalls of America’s Alliances with Authoritarian Regimes.44 This examines Washington’s relations with a dozen different authoritarian rulers since World War II. Although most foreign policy analysts characterize successive presidential administrations according to their words, their deeds—as these two books show—reveal a bizarre mishmash, at once incoherent and imprudent, between revolutionary and counterrevolutionary tendencies in U.S. policies. Both strains were antithetical to the older teaching, which bid this nation, as all nations, to neither suppress nor abet revolutions in other governments.45

However misguided America’s enterprises in the Global South have been, the United States in the past at least had candidates to replace the existing regimes. Today, in Afghanistan and Syria, the United States continues to impose a withering economic embargo on both states but has no plausible candidates to replace their existing rulers. Its aim seems to be the perpetuation of as much misery and anarchy as the peoples of the two territories can bear. For what earthly purpose? It cannot be to defeat terrorism, as terrorists invariably find their greatest room for maneuver when state authority has collapsed. It cannot be to build democracy, as that requires deliberation, not desperation, in the people. It cannot be to promote human rights, as both places are stalked by famine in which the most basic of human rights, to life itself, hangs by a thread. One cannot believe Americans, if fairly appraised of the situation, would approve the starvation of little children as a means to get the Taliban to respect women’s rights, but that is effectively the policy of the United States government.

Washington’s embrace of “regime change” as both a right and a duty for the United States took place at a time of great optimism, as President George H.W. Bush’s effusive celebration of freedom in his inaugural address makes plain. The era in which it was hatched, the 1980s, saw peoples in South America, East Asia, Eastern Europe, and Southern Africa hitch a ride on the democratic wave. While some of these changes were provoked by American power, like the surrender of Paraguay’s old dictatorship to democracy, what made them prevail was the idea of democracy that came to be held in the eyes of their peoples. What it was in the abstract, after all, could only be understood by looking at it concretely, and here the United States seemed to provide the example of a successful country that had proved a lot better than its ideological competitors in delivering the goods that people wanted.

At the very moment, then, when the power of the American example in changing the world was most potent, policymakers began thinking of changing the world through coercion. Great results were expected from that coercive campaign; the celebrations that had rocked Europe in 1989, bringing down communist autocrats, were expected to roll on throughout the world. It turned out, however, that the United States could not force the process, and for the simplest of reasons. For it to be durable, the peoples had to want it and to build it for themselves. They could not be forced to conform to a script written by outsiders, however lovely the words.

The failure of this enterprise was predictable. Indeed, it was predicted. Writing in 1951 in Foreign Affairs on “America and the Russian Future,” George Kennan observed: “The ways by which peoples advance toward dignity and enlightenment in government are things that constitute the deepest and most intimate processes of national life. There is nothing less understandable to foreigners, nothing in which foreign interference can do less good.”46

Democracy, autocracy, and the Biden Doctrine

The previous efforts to advance democracy through instruction, war, and sanctions have culminated today in the Biden Doctrine, which understands the central problem and challenge for the United States to be the great battle between democracy and autocracy. “Over the last 30 years, the forces of autocracy have revived all across the globe,” said President Biden in his speech at Warsaw Castle in April 2022. Ironically, it was in that very period of America’s undisputed prominence as the unipolar power that this revival took place. Freedom House reports that 2021 “marked the 15th consecutive year of decline in global freedom,” with the countries experiencing deterioration outnumbering those with improvements by the largest margin since 2006, when the negative trend began.47 Autocracy advanced, in other words, just at the moment when the defeat of tyranny became America’s foremost objective. That fact doesn’t speak especially well of the prospects of President Biden’s crusade for democracy.

The autocratic world is easily identified. It consists of more than half the world’s states. Its most prominent members from the U.S. perspective are China, Russia, and Iran. The democratic camp, however, has a more uncertain shape. Practically speaking, it consists of the West and East wings of the American alliance system—the democracies of Europe and North America, together with Japan, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand—with Ukraine in the West and Taiwan in the East often treated and described as “allies” though they have no security treaty with the United States. The states within this enlarged “West” seek or gain protection from their U.S. ties and together constitute the preponderance of the world’s wealth, as measured by GDP and stock market capitalization. For all that, they are by population only one-eighth of humanity. When we venture outside this charmed circle, we encounter figures—Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, Saudi Arabian Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, and Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi—whose trademark style is contempt for certain features of liberal democracy—despite most of them having come to power through elections.

The Summit for Democracy

The invitation list to the Biden Administration’s 2021 Summit for Democracy includes a wide range of nations from the Global South whose democratic credentials might well be challenged. Very few of the invited states outside the West can be said to be part of a “democratic coalition.” They all oppose, for instance, the unilateral or secondary sanctions imposed with growing frequency by the United States. Invited states from the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) want good relations with states from ASEAN that were not invited to the summit. Turkey was not invited, though a member of NATO. India and Pakistan are deeply at odds with one another, showing the fictitiousness of the “democratic camp” as a real geopolitical concept in the Global South. Many of the African states invited have very troubled histories by way of ensuring fair elections and respect for individual rights. Angola, an important oil producer, has a constitution vesting total control in the president, a post held by one man, José Eduardo dos Santos, from 1979 to 2017. There a tiny oligarchy, living in luxury, rules over masses beset by squalor.48

President Biden’s Summit for Democracy in 2021 was weak tea by comparison with the League of Democracies promoted by Sen. John McCain in his 2008 presidential bid, long a favorite concept among neoconservative writers.49 The effective aim of such a grouping would be to displace the U.N. as the world’s leading security organization. But very few if any of the states of the Global South, including those invited to the 2021 meeting, would favor that arrangement. The United States might see a League of Democracies as a bid to lead the world, but a majority of the world’s peoples would see such an alliance as a secession from it.

Inconsistent standards

Washington does not adhere to a consistent standard in its approach to democracy and human rights. As State Department official Brian Hook explained to Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, then newly appointed by Donald Trump, “allies should be treated differently—and better—than adversaries.” The United States should stand up for principle sometimes but not all times. Against adversaries such as China, Russia, North Korea, and Iran, Hook explained, human rights should be considered an important issue, because “we look to pressure, compete with, and outmaneuver them.” But “U.S. allies such as Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the Philippines” should be treated differently. This flexible attitude, otherwise known as hypocrisy, allows for the weaponization of principle against adversaries but avoids the coercion of friends.50

Countries and governments invited to the 2021 Summit for Democracy

The 2021 Summit for Democracy reflects the Biden Administration’s attempt to put democracy promotion at the center of U.S. foreign policy, but the 110 nations invited reflect neither a coherent geopolitical concept nor a common commitment to liberal democracy.

What makes the stark contrast between democracy and autocracy especially misleading is that it mischaracterizes what is at stake in the clashes among the nations. While autocratic governments do not represent the will of their people in some respects, they do represent the will of their people on most questions of foreign policy. China has a set of interests on a dozen different questions that would make for continuity of policy in the unlikely event it made a successful transition to a representative constitutional democracy. It might, in those circumstances, be even more avid in bringing Taiwan under its jurisdiction. Russia’s democratic government in the 1990s, such as it was, objected to NATO expansion and Western intervention in the Balkans, just as Russian President Vladimir Putin would later do; even Alexei Navalny, erstwhile leader of Russia’s liberals, supported Russia’s 2008 war against Georgia and the 2014 annexation of Crimea. No government in Iran, were democracy to replace the rule of the mullahs, would accept discriminatory treatment in the application of the rules of the Non-Proliferation Treaty.51 By personalizing foreign policy disputes and making it all about President Putin, President Xi, and other hated leaders, the nations they lead are blotted out of the account. If all nations have equal rights, as was once a central part of the American creed, that attribution is both a philosophical mistake and an invitation to imprudent action.

Surveying the multiple conflicts in the world, they are invariably best understood as conflicts of nationalities, riven by conflicting conceptions of what belongs to them and what belongs to others. The form of government may affect the conception of national interest held by these conflicting nationalities and their leaders, but the core of their political conflict would in most cases persist even with a change in regime. Democratic peoples, no less than autocratic leaders, are capable of great bellicosity.

If the United States is inconsistent in its approach to sanctions against offenders against democracy and human rights, its conception of human rights has also undergone substantial change. It used to mean the cherished rights identified in the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Today, at least judging by the attention given to the issue by the U.S. State Department, its foremost feature is a dedication to the rights of LGBTQI+ persons. That seems more like a transplantation of America’s culture wars onto the world than a steadfast policy for which there is a domestic consensus in the United States. If taken seriously, it is certain to generate huge resentment in the Islamic world.52

Americans take it as a self-evident truth, or used to, that a state that suppresses free thought is injuring its nation, for every nation needs the creativity that only free thought can produce. That self-evident truth surely holds for China, Russia, and Iran, as it does for the autocratic states with which the United States maintains friendly ties. Lest we forget, it holds for the United States itself.53 At the same time, the measures the West takes against these governments have the invariable effect of hurting those very forces in their own societies that are most amenable to some form of “westernization.” There are innumerable casualties to be found in Russia’s response since 2014 to Western sanctions, most of which fell on organizations that sought to build a bridge between the two cultures. The latest organizations to get the axe (15 in all) include the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, the Friedrich Naumann Foundation for Freedom, the Friedrich Ebert Foundation, and the Aga Khan Foundation.54 The enforced breakage of communication between East and West, now considered a moral imperative, is ominous for world peace, as nations who do not communicate have little hope of understanding the other’s way of thinking. How then can they know the other’s red lines?

Disguising the stakes

Perhaps the greatest problem that arises from framing the issue of foreign policy as “democracy vs. autocracy” is it disguises the real stakes for the United States. Consider the transformation of NATO, formed between the United States and its democratic partners in Western Europe after World War II. Whereas the old NATO was a defensive alliance—forged to deter Soviet aggression against Western Europe—post-Cold War NATO became a platform for U.S. intervention in places like Libya. It also became committed to the principle of unlimited expansion, something that was not forbidden by its Charter but by no means required by it. In contrast to today’s policy, NATO back then was willing to accept “neutralization” as an eligible formula for security, as it did in the case of Austria in 1955. The admission of Greece and Turkey in 1952 was widely seen as the ne plus ultra of expansion to the East, as they had called it the North Atlantic Treaty for a reason. Subsequent ventures in collective defense took the form of regional associations like SEATO and CENTO.

The most consequential change of European policy in the unipolar era was the rejection by President George W. Bush of Ukrainian neutrality. His father, by contrast, had warned of the dangers of “suicidal nationalism.” Bush II wanted to put Ukraine on a fast track to membership in NATO. The European allies demurred on the “fast track” option but compromised and signed on at the 2008 Bucharest Summit to the principle of expansion at some time in the future.55 This posture had unfortunate political effects. It convinced Russia the United States and the West were hostile to its vital interests; it encouraged Ukrainian nationalists to press hard against the Russophone population in Ukraine. That proved the perfect formula for a war and was at play in both 2014 and 2022.56

A second objection to the current structure of alliance obligations is it imposes unfair burdens on the American people. An annual disparity of 3 percent of GDP in “defense” expenditures may not sound like much, but over time it inevitably impinges on domestic welfare, whether through onerous taxes, increased debt, or crowding out expenditures needed at home, like long-delayed programs to upgrade the nation’s infrastructure. In statecraft, a classic piece of wisdom is to warn against making foreign policy a mere matter of the counting shop, of dollars and cents, but this is a permanent disability, a structural disadvantage that impairs the well-being of the American body politic.

A third deficiency with this arrangement is it relieves the nations under the wing of American protection of the need to take measures for their own security. The old rule was that each nation was to take care of itself. Singly, each people could summon great resources in resistance to external conquest, and if weak by itself could ally with others in its neighborhood. It is understandable why, in the twentieth century, America focused on the need for union and saw itself at the head of the posse to combat aggression. It had the memory of Adolf Hitler and World War II as a standing lesson of the need to establish enduring friendships among nations closely aligned in belief over the fundamentals.

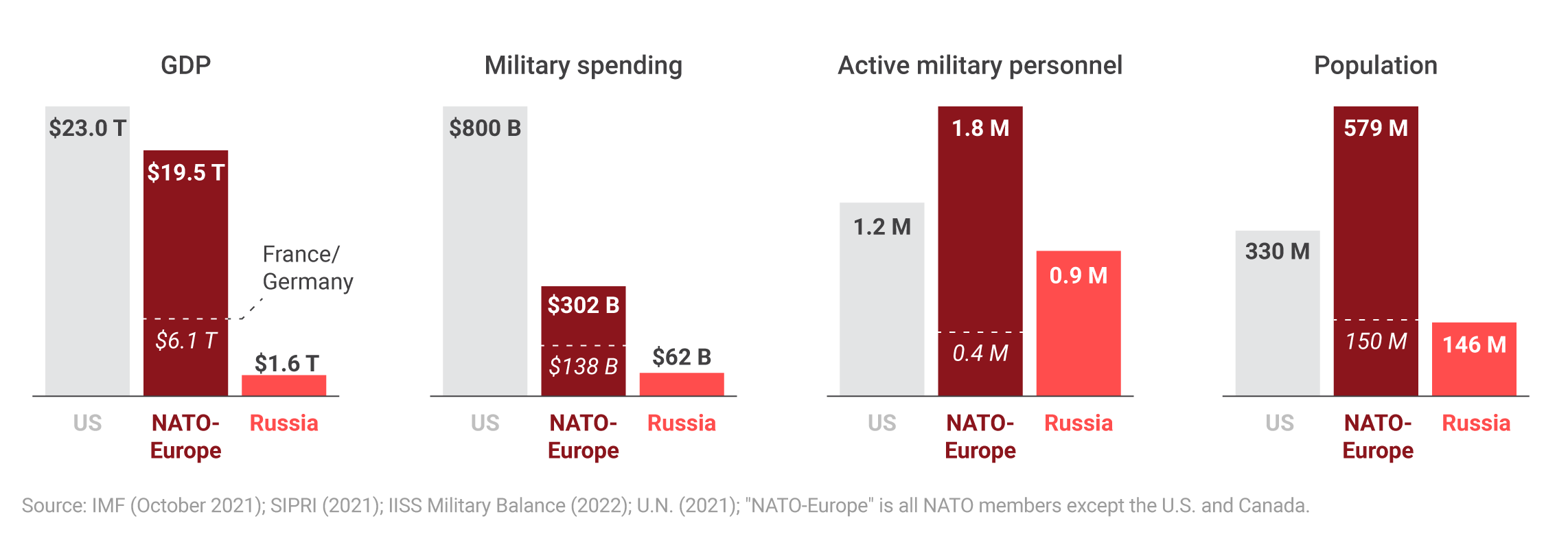

THE BALANCE OF POWER BETWEEN NATO-EUROPE AND RUSSIA

The U.S. security umbrella in Europe is an emblem of the great conflict that Biden has posed between democracy and autocracy, but it has fostered dependence, not self-rule, among the nations of Europe. Though Russia generates far more effective military power than the $62 billion figure would indicate, America’s European allies clearly have the economic capacity to end their dependence on the United States and provide for their own defense.

When that mission was undertaken, however, the common expectation was that it was not to last forever. President Eisenhower was insistent on the point that time would bring a more balanced relationship between protector and protected. Unfortunately, America’s allies never got that memo, largely because the U.S. government failed to send it. U.S. leaders gave speeches to that effect, to be sure, but all these meant was that the allies were expected to buy U.S.-manufactured arms. Under the American security umbrella, the allies scarcely developed past adolescence and retain to this day the classic marks of infancy—the well-known inability to get along without protective parents. In 2020, the GDP of European countries in NATO totaled $19.5 trillion; that of Russia, $1.66 trillion, more than 9 times larger. NATO military expenditures outpace Russia many times over. The disparity between U.S. and allied defense expenditures suggests the United States cares more for the security of allies than allies do themselves. In most locales, its novel political theology became the implausible doctrine that God helps those who do not help themselves.

This arrangement has worked splendidly for the U.S. national security state, whose interests are distinct from those of the American people. Politically, it presents a situation of concentrated benefits and diffuse costs, giving the security establishment a potent electoral advantage.57 In most states and congressional districts, spending on the military has a core constituency that is seen to hold the balance of political power, thus an interest not to be offended.58 This situation also helps explain the strange anomaly that non-interventionist voices, a half or more of public sentiment, should have little representation in Congress. In an era in which the Republican and Democratic leadership in Congress are deeply estranged, recalling the irreconcilable conflicts of the 1850s, the one thing they can agree on is steady increases in the defense budget.59

U.S. leaders have said for a generation that the allies were to step up and assume the burdens, but the real meaning was that they were to sign on to American purposes in thus increasing their contribution to the common till. They weren’t particularly keen on that and got the protection regardless, so generally didn’t bother. That reasoning is perfectly understandable. It is also perfectly obvious that the great disparity in contribution works to the disadvantage of the American people.

But the most important reason for reconsidering these alliances is the threat they have come to pose to American security. They are ostensibly about providing for that security—that is their announced mission—but the consequence of U.S. commitments is a set of war crises, singly and collectively, with Russia, Iran, China, and North Korea. President George W. Bush promised a world of such overwhelming U.S. military power that no others would dare challenge it. Experience has shown that expectation to have been incorrect. Rather than a barrier to war, U.S. alliances function as a transmission belt to U.S. involvement.60

From liberty to force

These worldwide commitments pose a critical question for Americans to consider. One of the oldest lessons in the traditional American philosophy of international relations is that force holds a logic that is ultimately inimical to liberty. Nations at war become less free and more regimented. As Alexander Hamilton expressed this idea, war compels “nations the most attached to liberty to resort for repose and security to institutions which have a tendency to destroy their civil and political rights. To be more safe, they at length become willing to run the risk of being less free.”61 John Quincy Adams spied the same danger, noting that if America enlisted in the wars of others “the fundamental maxims of her policy would insensibly change from liberty to force.” The excesses of the war on terror and the creation of a surveillance state of universal penetration bear out Adams’s prophecy.

An international environment distinguished by the threat of constant war, moreover, tends to encourage the modern equivalent of the “man on horseback”: the strong leader who will defend the nation against its enemies. The strong leaders who populate most of the world’s big states are strong most of all for their nation, under perceived attack by foreign adversaries. Such types tend to be less powerful, or less attractive to their people, in a less conflictual foreign environment. On this accounting, the overall dynamic is not that democracy leads to peace, but rather that peace is the condition most favorable to the growth of democracy.62

The most potent objection against America’s formula of democratic universalism—apart from its failures in Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, and Syria—is that it puts the United States in a state of remorseless conflict with non-democratic countries. America’s formula of “ending tyranny,” in fact, almost exactly describes the conditions under which Immanuel Kant defined the “unjust enemy”—”it is an enemy whose publicly expressed will (whether by words or deed) reveals a maxim by which if it were made a universal rule, any condition of peace among nations would be impossible and, instead, a state of nature would be perpetuated.”63 By stating the cause of war or sanctions as the “being,” rather than the “doing,” of an undemocratic state, the United States puts itself in a posture that poses enormous obstacles to peace. It aims its coercive measures against the rulers, but the burdens, sure to be resented, fall on the people. In principle, this revolutionary purpose brings us much closer to a lawless international system, a state of nature tending toward war.

The primacy of foreign policy

The conviction of the Washington-based national security establishment is that the security, prosperity, and freedom of the American people can only be achieved if the United States seeks the reformation of the world. They have been looking abroad for the formula by which to secure the advance of democracy and the preservation of peace. They have asserted, in effect, the primacy of foreign policy as the rule by which America’s public household is managed. Unless democracy prevails everywhere, it will be imperiled at home.

Although they may believe it, it really isn’t true. Indeed, the quality of American democracy has manifestly been impaired by its extensive global commitments. When President Wilson bid America to join the League of Nations and to commit itself against aggression, the alternative world he conjured was a set of institutions at home that would be fatal to liberty: vastly enlarged executive powers, “a great standing army,” “secret agencies planted everywhere,” “universal conscription,” “taxes such as we have never seen,” restrictions on the free expression of opinion, a “military class” that would dominate civilian decision-making—all of it “absolutely antidemocratic in its influence” and representing an “absolute reversal of all the ideals of American history.”64 Not all the elements in President Wilson’s dark prophecy came true, but many of them did; moreover, they did so as a consequence of America’s global military commitments, not because it retreated into political isolation after World War I. So acclimated are the contemporary generations of Americans to these institutions that they seem like a normal part of the democratic scenery. President Wilson recognized them to be in downright contradiction with the democratic ideal he held in his minds’ eye.

Whether America entertains modest or ambitious objectives in the world, it needs a foreign policy, but the foreign policy adopted by the United States has been altogether too ambitious. It has sought the reformation of the entire world. It enlists valuable ideas like freedom and democracy in enterprises that have that as a rhetorical aim, but never as a practical effect. Its military expenditures constitute a burden on the well-being of its people. Its global commitments threaten its national security rather than ensuring it.

The realization we most need is that putting first the reformation of the world has meant putting last the things that ought most to concern us, which is the preservation of the security, freedom, and prosperity of the American people.65 Putting one’s own country first, to be sure, does not relieve any state or nationality of its duty to respect the obligations of good neighborhood, nor of making contributions to global goods. There are ways for nations to pursue their interests without committing a slew of injustices along the way, in basically the same way that ordinary people can become prosperous without robbing banks.

The United States could make a signal contribution to the world by ceasing to inflict injuries upon those parts of it that have run afoul of Washington’s campaign to extend democracy and human rights by external pressure. The injuries inflicted don’t actually cause the objects of U.S. power to mend their ways. American ideals, together with an inflated idea of its coercive power, encourage the American nation to a crusade that, intrinsically, it cannot win, because the world is too intractable in its many enmities and irresolvable conflicts. In trying to solve them by military intervention or the methods of the long-distance blockade, the sum total is just a lot of other-inflicted injuries, along with a now-growing list of self-inflicted ones.

Endnotes

1 Francis Fukuyama, “The End of History?” National Interest 16 (Summer 1989): 3–18.

2 Samuel P. Huntington, The Third Wave: Democratization in the Late Twentieth Century (Norman, OK: Oklahoma University Press, 1991).

3 George H.W. Bush, Inaugural Address, January 20, 1989, https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/news/inaugural-address.html.

4 “Excerpts from Shultz’s Speech Contrasting Communism and Democracy,” New York Times, February 23, 1985, https://www.nytimes.com/1985/02/23/world/excerpts-from-shultz-s-speech-contrasting-communism-and-democracy.html.

5 “Excerpts from Shultz’s.”

6 Ronald Reagan, Republican National Convention acceptance address, July 17, 1980, https://www.reaganlibrary.gov/archives/speech/republican-national-convention-acceptance-speech-1980.

7 M.E. Sarotte, Not One Inch: America, Russia, and the Making of Post-Cold War Stalemate (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2021).

8 Thomas Jefferson to John Adams, May 17, 1818, in The Adams-Jefferson Letters, ed. Lester J. Cappon (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1959), 524.

9 “Pacificus No. 2, July 3, 1793,” The Papers of Alexander Hamilton, ed. Harold C. Syrett et al., vol 15, (New York: Columbia University Press, 1961–1979), 59–62.

10 Theodore Christov, “Emer de Vattel’s Law of Nations in America’s Independence,” Justifying Revolution: Law, Virtue, and Violence in the American War of Independence, eds. Glenn A. Moots and Phillip Hamilton (Norman, OK: Oklahoma University Press, 2018), 64–82; Otto Gierke, Natural Law and the Theory of Society, 1500—1800 Introduction by Ernest Barker, introduction to Natural Law and the Theory of Society, 1500—1800 (Boston, MA: Beacon Press, [1934] 1957), xlvi–xlvii.

11 Brendon Simms and D.J.B. Trim, eds., Humanitarian Intervention: A History (Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press, 2011); Gary J. Bass, Freedom’s Battle: The Origins of Humanitarian Intervention (New York: Vintage, 2008).

12 See essays on Adams, Webster, and Seward in Norman A. Graebner, ed., Traditions and Values: American Diplomacy, 1790–1865 (Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1985). The classic statement is John Quincy Adams, An Address . . . Celebrating the Anniversary of Independence, at the City of Washington on the Fourth of July 1821, Upon the Occasion of Reading the Declaration of Independence (Washington, DC: Davis and Force, 1821).

13 President Wilson’s place in the U.S. diplomatic firmament has attracted enormous interest from historians and political scientists. President Wilson’s zealotry is stressed in Walter A. McDougall, Promised Land, Crusader State: The American Encounter with the World since 1776 (Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin, 1996) and Walter A. McDougall, The Tragedy of U.S. Foreign Policy: How America’s Civil Religion Betrayed the National Interest (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2016). Presenting a somewhat more moderate picture of Wilsonian objectives are Michael Lind, The American Way of Strategy (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2006); David C. Hendrickson, Union, Nation, or Empire: The American Debate over International Relations, 1789–1941 (Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2009); G. John Ikenberry, A World Safe for Democracy: Liberal Internationalism and the Crises of Global Order (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2020); and Tony Smith, Why Wilson Matters: The Origin of American Liberal Internationalism and Its Crisis Today (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2017). The best short introduction is John A. Thompson, Woodrow Wilson (London, UK: Routledge, 2002).

14 Michla Pomerance, “The United States and Self-Determination: Perspectives on the Wilsonian Conception,” American Journal of International Law 70 (1976): 1–27. See parallel discussion in David C. Hendrickson, “Sovereignty’s Other Half: How International Law Bears on Ukraine,” The Institute for Peace and Diplomacy, May 17, 2022, https://peacediplomacy.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Sovereigntys-Other-Half-%C2%B7-How-International-Law-Bears-on-Ukraine-1.pdf.

15 “Woodrow Wilson, Address to Congress, January 22, 1917,” UVA Miller Center, https://millercenter.org/the-presidency/presidential-speeches/january-22-1917-world-league-peace-speech.

16 “Remarks to Foreign Correspondents, April 8, 1918,” in Thompson, Woodrow Wilson, 169.

17 The keen interest aroused among the nations subject to European imperialism by Wilson’s call for self-determination is traced in Erez Manela, The Wilsonian Moment: Self-Determination and the International Origins of Anticolonial Nationalism (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2009).

18 Roosevelt quoted in David Fromkin, In the Time of the Americans: FDR, Truman, Eisenhower, Marshall, MacArthur—The Generation That Changed America’s Role in the World (New York: Random House, 1995), 591.

19 “The North Atlantic Treaty,” North Atlantic Treaty Organization, April 4, 1949, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natolive/official_texts_17120.htm.

20 Lindsey O’Rourke, Covert Regime Change: America’s Secret Cold War (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2018); Tim Weiner, Legacy of Ashes: The History of the CIA (New York: Doubleday, 2007); Stephen Kinzer, The Brothers: John Foster Dulles, Allen Dulles, and Their Secret World War (New York: Times Books, 2013).

21 Walter Lippmann, The Cold War: A Study in U.S. Foreign Policy (New York: Harper & Row, 1972 [1947]).

22 Dwight D. Eisenhower, “Inaugural Address,” The American Presidency Project, https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/inaugural-address-3.

23 John F. Kennedy, “Commencement Address at American University, Washington, DC, June 10, 1963,” John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, https://www.jfklibrary.org/archives/other-resources/john-f-kennedy-speeches/american-university-19630610.

24 Bernard Brodie, Strategy in the Missile Age (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 1959), 269.

25 Enea Gjoza, “Counting the Cost of Financial Warfare,” Defense Priorities, November 11, 2019, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/counting-the-cost-of-financial-warfare.

26 Carl Gershman, “Former Soviet States Stand Up to Russia. Will the U.S.?” Washington Post, September 26, 2013, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/former-soviet-states-stand-up-to-russia-will-the-us/2013/09/26/b5ad2be4-246a-11e3-b75d-5b7f66349852_story.html.

27 For numerous expressions of this theme, see David C. Hendrickson, Peace Pact: The Lost World of the American Founding (Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2003), and ibid Union, Nation, and Empire. That America’s ‘young democracy’ contained combustible elements is shown in Richard Kreitner, Break It Up: Secession, Division, and the Secret History of America’s Imperfect Union (New York: Little Brown, 2020); and Elizabeth R. Varon, Disunion! The Coming of the American Civil War, 1789–1859 (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2010). The means of its preservation are detailed in Peter B. Knupfer, The Union as It Is: Constitutional Unionism and Sectional Compromise, 1787–1861 (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1991); and Paul C. Nagel, One Nation Indivisible: The Union in American Thought, 1776–1861 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1964).

28 Nicolai N. Petro, “America’s Ukraine Policy Is All About Russia,” National Interest, December 6, 2021; Ted Galen Carpenter, “Washington’s Foreign ‘Democratic’ Clients Become an Embarrassment Again,” Cato Institute, February 18, 2021, https://www.cato.org/commentary/washingtons-foreign-democratic-clients-become-embarrassment-again; “Council of Europe’s Experts Criticize Ukrainian Language Laws,” RFE/RL, December 7, 2019.

29 See further David C. Hendrickson and Robert W. Tucker, Revisions in Need of Revising: What Went Wrong in the Iraq War (Carlisle, PA: Army War College, Strategic Studies Institute, 2005).

30 Dominic Tierney, “The Legacy of Obama’s Worst Mistake,” Atlantic, April 15, 2016, https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2016/04/obamas-worst-mistake-libya/478461.

31 “Libya: New Evidence Shows Refugees and Migrants Trapped in Horrific Cycle of Abuses,” Amnesty International, September 24, 2020, https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2020/09/libya-new-evidence-shows-refugees-and-migrants-trapped-in-horrific-cycle-of-abuse.

32 “Foreign Terrorist Organizations,” Bureau of Counterterrorism, https://www.state.gov/foreign-terrorist-organizations.

33 The contention the occupation of Germany and Japan show that force can build democracy misses two other pertinent facts. Both countries had committed large-scale aggression and were destroyed in their turn, their cities reduced to ashes. That was something of a condition precedent for the subsequent reconstruction. No such sequence was imaginable in the cases of Afghanistan et al. The United States, moreover, did not go to war in 1941 to “advance democracy” but to defeat Germany and Japan. In the next three and a half years they did so remorselessly, with almost no thought given to life after V-Day. The duty to reconstruct those societies followed from the fact of occupation, for which representative democracy seemed not unreasonably the best choice, though with safeguards to ensure against a return to bad habits by the aggressor nations. Put in the language of the law, democracy building was not part of jus ad bellum, the reasons offered for going to war, but of jus post bellum, that is, the duties falling on occupiers to treat the conquered with respect for their human rights.

34 Daniel Webster, “The Character of Washington,” The Works of Daniel Webster, ed. Edward Everett, February 22, 1832, (Boston, MA: Wentworth Press, 1851), 230.

35 Larry Diamond, Squandered Victory: The American Occupation and the Bungled Effort to Bring Democracy to Iraq (New York: Times Books, 2005).

36 The U.S. approach to democracy building in Iraq is reflected in the comments of Gen. James Mattis, the Marine commander in Iraq who became Trump’s Secretary of Defense: “Be polite, be professional, but have a plan to kill everybody you meet.” And this: “I come in peace. I didn’t bring artillery. But I’m pleading with you, with tears in my eyes: If you fuck with me, I’ll kill you all.” These methods, needless to say, do not appear in Robert’s Rules of Order. Mattis is cited in Thomas Ricks, “Mattis as Defense Secretary,” Foreign Policy, November 21, 2016, https://foreignpolicy.com/2016/11/21/mattis-as-defense-secretary-what-it-means-for-us-for-the-military-and-for-trump/.

37 Nicholas Mulder, The Economic Weapon: The Rise of Sanctions as a Tool of Modern War (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2022).

38 Oona A. Hathaway and Scott J. Shapiro, The Internationalists: How a Radical Plan to Outlaw War Remade the World (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2017).

39 David Miliband, “The Afghan Economy is a Falling House of Cards,” CNN, January 20, 2022. https://www.cnn.com/2022/01/20/opinions/afghan-economy-falling-house-cards-miliband/index.html.

40 Miliband, “The Afghan Economy.”