Key points

Questions about nuclear use should be foremost in U.S. defense planning debates over Taiwan and policy discussions on maintaining strategic ambiguity.

If China moves against Taiwan, the stakes will be life-and-death for China’s leadership, given the potential political and personal consequences should an invasion fail.

In the face of battlefield defeats or setbacks, China could find itself more willing to use nuclear weapons, even if it had not intended to do so before the conflict.

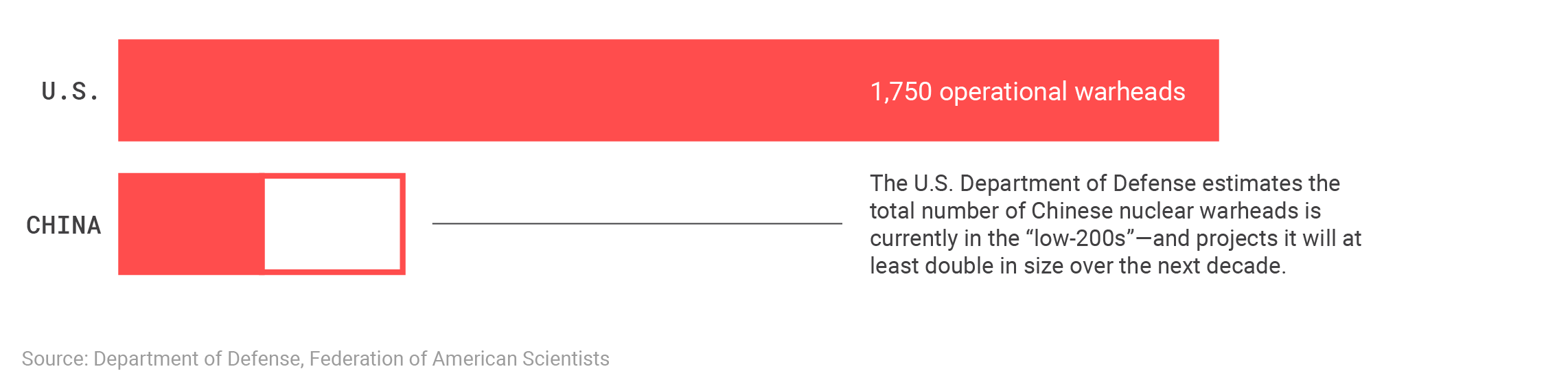

China’s nuclear arsenal is significantly outnumbered by that of the United States, but China maintains sufficient strategic forces that it could still inflict unacceptable damage on some U.S. cities.

The U.S. style of warfare, coupled with China’s co-mingling of its conventional and nuclear missile forces, creates the opportunity for inadvertent escalation if U.S. forces were to unintentionally strike Chinese strategic assets.

As discussion intensifies over U.S. policy toward Taiwan under the new Biden administration, nuclear issues should be at the core of that debate. Various proposals have been put forth for and against abandoning the concept of strategic ambiguity, and it is an important discussion to have. But unless nuclear stability between China and the United States is at the forefront of that discourse, it misses the central question regarding how and whether the United States should defend Taiwan.

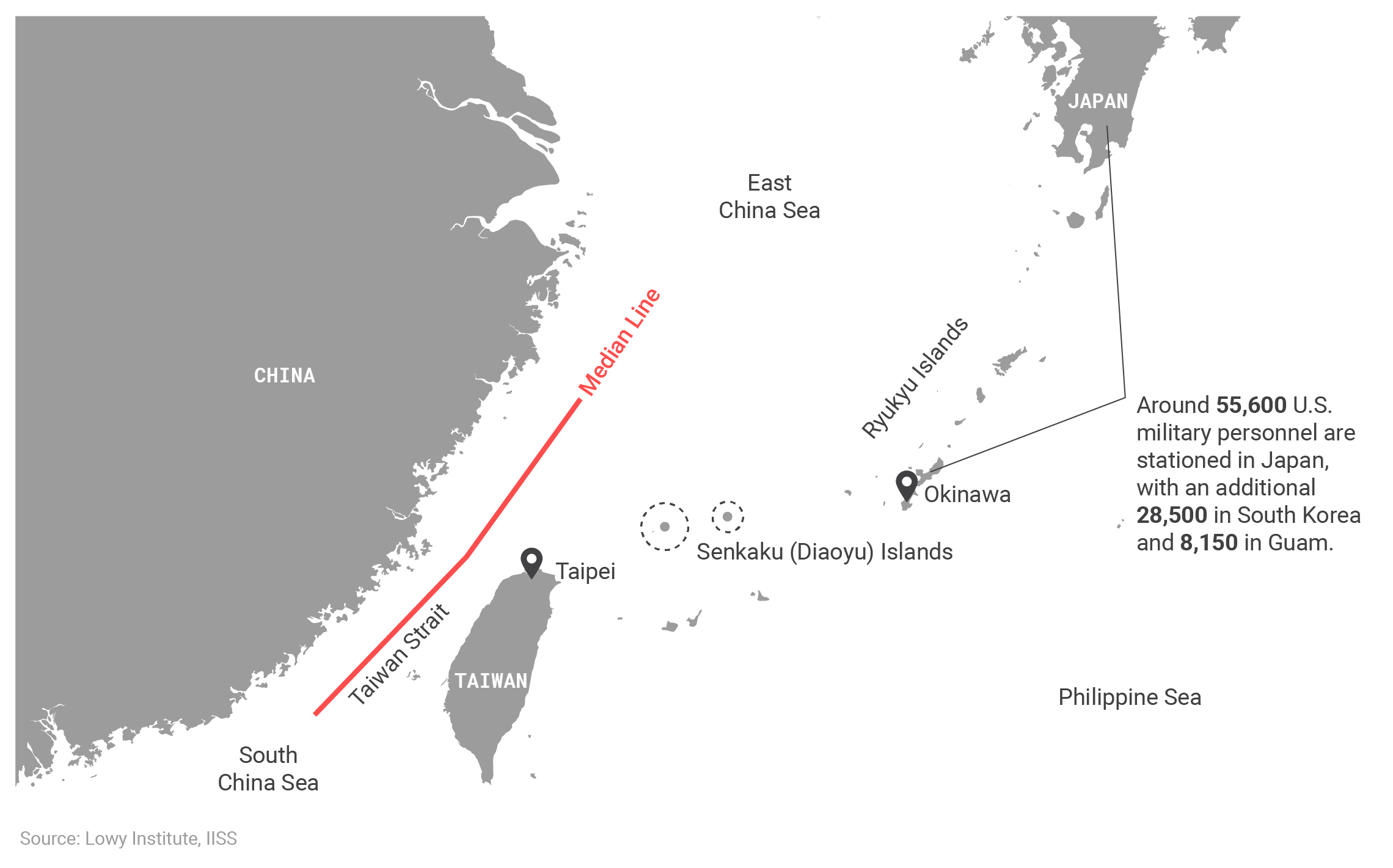

Taiwan’s strategic environment

Approximately 100 miles from mainland China, Taiwan is sensitive to Chinese incursions across the so-called “median line” that bisects the Taiwan Strait. Disputed islands and a large U.S. military presence are also nearby.

The battle over fighting for Taiwan

From 1954 onwards, the United States and the Republic of China (ROC), informally known as Taiwan, had a mutual defense treaty that committed America to the ROC’s defense. The United States based forces on the island, including nuclear weapons,1 at various points in support of this commitment, which was abrogated in 1979 in deference to the normalization of diplomatic relations between the United States and the People’s Republic of China (PRC).2 In the treaty’s place, Congress passed the Taiwan Relations Act (TRA) which requires the United States to a) equip Taiwan with the means to defend itself and b) necessitates the United States “maintain the capacity” to resist efforts aimed at infringing on Taiwanese security and freedom.3

However, the TRA does not definitively state whether the United States should use said “capacity” in the event Taiwan is actually threatened with invasion or other forms of coercion designed to formally bring the island under the PRC’s direct rule. Subsequent U.S. administrations have left the answer unclear, though some have leaned closer to outright support than others.4 Collectively, the policy of never officially declaring how the United States would respond in the event of a direct threat from the mainland against Taiwan has been known as strategic ambiguity.

For most of the forty years in which it held sway, strategic ambiguity was abetted by China’s inability to seriously threaten Taiwan with invasion. Even now, the challenges inherent in an amphibious assault across the 100-mile Taiwan Strait remain formidable.5 Despite its impressive naval build up, amphibious lift remains a weak point for China. A 2020 assessment by the Department of Defense (DoD) found China is not investing in the necessary amphibious capabilities required for a major beach landing at this time.6

That said, China does possess other means of indirectly coercing Taiwan through force, including air power and missiles capable of strategic bombardment and naval forces which could attempt to blockade the island.7 And China’s ability to contest its littoral waters has increased dramatically over the past quarter century, creating challenges for the U.S. Navy even outside the specific context of Taiwan contingencies.8

In general, as China’s conventional capabilities continue to mature, the prospect of direct action against Taiwan will only become more realistic. This, in turn, has forced a renewed debate over strategic ambiguity, with some commentators calling for greater fidelity on the issue—i.e., “strategic clarity”—as a way to make U.S. intentions plain, ideally to deter China from military action. More nuanced takes on the policy argue not for explicit U.S. support to Taiwanese independence, but rather for an express rejection of any attempt by China to settle the issue by force.9 (Whether such a declaration might, in turn, provoke Beijing to act or overly embolden Taipei is the other side of that argument.)10

At the same time as there is renewed debate over strategic ambiguity, the Department of Defense has designated China as the “pacing threat” for the U.S. military services in their programs and training.11 In other words, Chinese capabilities are now the threat against which the services must essentially take their own measure. U.S. ability to ensure freedom of navigation in the Asian littoral seas (i.e., the South and East China Seas and the Yellow Sea) has already become an important element in operational concepts for all four services. Some analysts have gone so far as to state that defending Taiwan should be the explicit guiding scenario for U.S. force planning and strategy.12 Possible clandestine training missions by Marine Corps special forces in Taiwan during 2020 add weight to such public deliberations.13

Yet significant in the debate over both strategic ambiguity and defense planning for Taiwan-related scenarios has been a consistent lack of attention to nuclear matters.14 Indeed, whereas nuclear considerations are central to discussion of potential conflicts between the United States and Russia, they are surprisingly lacking in similar examinations of U.S.-Chinese conflicts. As will be discussed below, U.S. strategic forces significantly outnumber those of China, but that does not inherently mean either side could not resort to nuclear use in the event of open conflict, particularly over Taiwan.

Parsing China’s “no first use” policy

Even as its geopolitical clout has risen considerably, China’s nuclear arsenal has remained modest. Most Americans would be surprised to learn China has only the world’s fourth biggest nuclear force. China’s operational warhead stockpile is estimated by the Department of Defense to number “in the low 200s,” roughly on par with the United Kingdom’s 215 weapons and less than France, currently the third largest nuclear power with about 290 warheads.15 The Department of Defense does expect China’s nuclear force to more than double over the next decade, but even at 500 weapons, China’s would lag far behind the U.S. arsenal, which features 1,750 operational warheads, plus another 2,050 in reserve.16

China has maintained a “no first use” (NFU) policy since the inception of its nuclear capability, meaning it asserts to never be the party that will initiate a nuclear conflict. Unlike the Soviet Union, whose NFU policy was largely seen as propaganda, China’s commitment to its NFU stance appears more genuine, at least as a starting point for understanding Chinese thinking on nuclear employment.17 That said, much about Chinese nuclear doctrine and decision-making remains opaque, with ultimate authority left to the Central Military Committee of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), which includes, most prominently, President Xi Jinping.18 The question of whether and when to use nuclear forces is thus—as in all nuclear states—ultimately malleable, a factor of the personal judgments and temperaments of those with control over weapons release.

Additionally, a range of writings exist within the Chinese military community on whether the NFU policy should eventually be abandoned, particularly if the vital interests of the Chinese state were at risk from conventional attack.19 Additional calls for the development of lower-yield warheads have also been proffered in Chinese defense literature.20 This at least suggests a possible future warfighting role for tactical nuclear weapons beyond just strategic retaliation. Western analysts have also noted that Chinese officials privately assert a conventional attack on Chinese strategic forces would allow for legitimate first use of surviving nuclear forces.21 China’s NFU pledge is thus more nebulous than it might seem and is open to subsequent evolution.

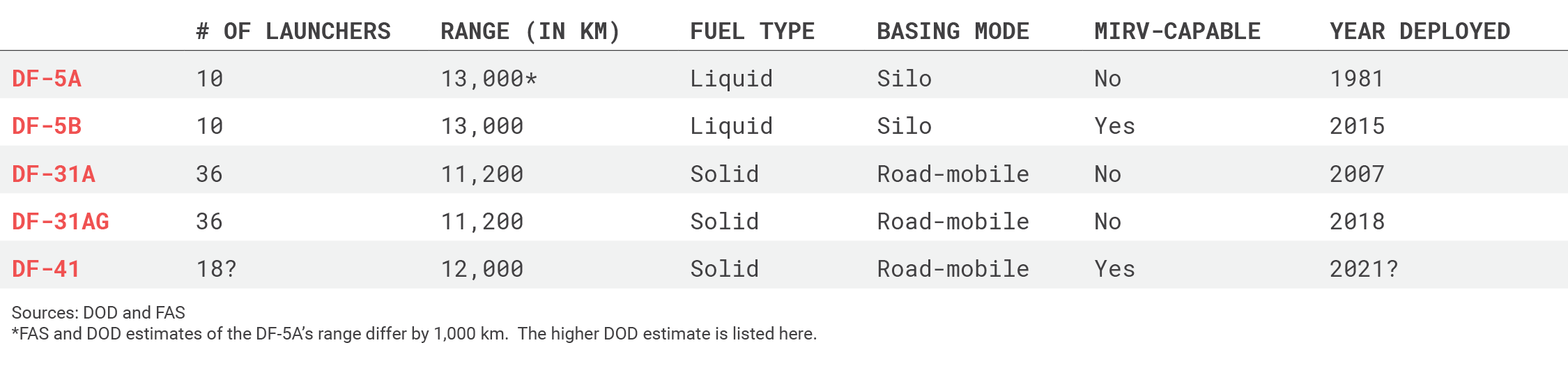

Assessing Chinese intercontinental nuclear strike capabilities

The Department of Defense’s assessments argue that enhancing survivability and second-strike capabilities are the focus in the expansion of China’s nuclear inventory and the development of new delivery systems.22 These will include more advanced mobile missile launchers on land and, eventually, a more robust sea-based deterrent to replace the current Jin-class of nuclear ballistic missile submarine (SSBNs) which suffer from deficiencies in acoustic quieting and missile range.23

Putting aside the limitations of its current sea-based deterrent, it is worth emphasizing that China could still inflict significant punishment on the United States with its land-based weapons. China has two types of intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) capable of hitting the contiguous United States—the older, silo-based DF-5 and the newer, road-mobile DF-31A and DF-31AG. A second road-mobile ICBM—the DF-41—is also in the early stages of being deployed but is not yet believed to be operational.24

Chinese ICBMs capable of striking the contiguous United States

The DF-5 can range most of the lower 48 states, including major East Coast cities, while the DF-31 variants can hold at risk cities in the Northwest and Upper Midwest.25 Once it is deployed, the DF-41’s reach will fall somewhere in between, with the ability to target the American Northeast and the western half of the country.26

The DF-41 is believed to have the capability to carry multiple independent re-entry vehicles (MIRVs), which essentially means several warheads can be carried by one missile or, a combination of warheads and decoys to help defeat U.S. missile defense interceptors.27 Over half the existing force of DF-5s (the DF-5B variant) also have a MIRV-capability of up to five warheads.28

China fields an estimated 36 DF-31As and another 36 DF-AGs; their road-mobility makes them extremely difficult to target, particularly in mountainous terrain.29 And the planned deployment of the DF-41 (possibly expected in the next year) will only enhance the overall survivability of China’s strategic forces, while adding additional MIRV-capable delivery vehicles. China also has a number of intermediate and medium-range missiles that can target both U.S. allies (such as Japan) and U.S. territories in the Pacific, like Guam.30

In a nuclear war with the United States, China could never hope to match the United States warhead-for-warhead as the Soviet Union once did (and as Russia still does). Instead, China would rely on the calculation that its ability to target at least some U.S. cities would make a nuclear exchange untenable for Washington. In truth, would the United States be willing to defend Taiwan if there was a legitimate prospect of a nuclear war, even one it might “win”? Would maintaining Taiwanese sovereignty be worth the cost of direct nuclear strikes on, say, Anchorage, Honolulu, Los Angeles, and Seattle even if the United States inflicted far greater devastation on Chinese cities? Would it be worth one of them?

Chinese ICBM coverage of the contiguous United States

China currently has two types of land-based ICBMs, the DF-5 and DF-31 variants, capable of striking the contiguous United States, with a third, the DF-41, developed but not yet operational.

The centrality of Taiwan in Chinese thinking

At this point, it is worth underscoring the obvious: Not all U.S.-China conflicts must inevitably end in a nuclear exchange. It is possible to imagine scenarios in which there is a military clash that remains limited to conventional forces. A war over the Senkakus in the East China Sea or the Spratlys in the South China Sea has less chance of escalating to the level of an existential conflict. But that is not true where those two seas meet: Taiwan. It is physically closer to the mainland—essentially China’s “doorstep”—and also occupies a far more prominent place in China’s national psyche. Taiwan is unlike any other issue in Chinese foreign policy precisely because that is not the prism through which Beijing views the island. Rather, it is a domestic issue. Put differently, for Beijing, Taiwan is already Chinese territory.31

While one can technically make the argument that China feels the same about various disputed islands in both the South and East China Seas, uninhabited atolls do not carry the same historical weight as Taiwan, not just for modern China but for the CCP itself. Since the end of the Chinese civil war in 1949, CCP leadership has sought to absorb the island. During the 1950s, a series of clashes played out between Communist and Nationalist forces on the ancillary islands of the Taiwan Strait, each of which ended with some form of U.S. intervention on the side of Taipei.

The intervening decades have done little to cool China’s enthusiasm for reunification. The early years of the post-Cold War world saw a revival in tension over Taiwan after the election of Lee Teng-hui, who was perceived by the mainland as overly assertive on Taiwanese sovereignty. Lee’s presidency sparked a renewed crisis in the Taiwan Strait during 1995 and 1996, with China employing missile tests and military exercises to deter action toward greater ROC independence.32 The Clinton administration responded at one point with the deployment of two carrier battlegroups, one of which sailed through the Taiwan Strait itself in a deliberate, high-profile show of force. China’s inability to deter those U.S. deployments is often viewed as a precipitating event for its ambitious program of naval modernization during the ensuing 25 years.33

In a recent survey of China’s grand strategy, political scientist Avery Goldstein argues that under President Xi Jinping there has been even less room for diffidence on China’s core interests than his immediate predecessors, with no concern more basic to the regime’s concept of identity than dominion over Taiwan.34 The island will remain an obsession for the Chinese leadership because, as Goldstein notes, the CCP long ago “identified restoring sovereignty over Taiwan as an essential part of the effort to recover territory China lost during the ‘century of humiliation.’”35 Reunification goes beyond a vital interest to a basic article of faith in China’s destiny.

Compounding matters, the Chinese public is likely to be deeply invested and supportive of a Taiwan campaign once begun. While polling in China is hardly an exact science, one study of multiple opinion surveys found a discernible hawkish bent among the Chinese populace, especially among the younger generations who have undergone so-called “patriotic education,” instituted in 1994.36 This particularly could be the case if U.S. forces were to attempt conventional strikes against air bases, missile launchers, radars, and other facilities on the Chinese mainland. Even though these are military targets, additional collateral damage and civilian casualties are likely. Such attacks could further inflame public sentiment in favor of the war—and against capitulation in the face of defeat—boxing in China’s leadership in the event of conventional setbacks.37

Finally, the existential nature of a potential Taiwan campaign is underscored by China’s understanding of its own military history. As naval scholar Toshi Yoshihara has pointed out, there is heightened recognition among the Chinese of the relationship between major defeat at sea and regime stability.38 For example, it is possible to draw a line from the Japanese destruction of the Qing Dynasty fleet at the Battle of the Yalu River in 1894 through to the Boxer Rebellion five years later.39 Fleets that take immense treasure and decades to construct can be destroyed in a matter of days (or even an afternoon) and the consequences for the nation seldom end with the loss of tonnage.

Maximalist aims will invite maximalist means

These factors raise an essential point in the calculation regarding Chinese nuclear use: how does any leader survive a defeat over a core tenet of modern Chinese identity like dominion over Taiwan? Or as Ambassador Chas Freeman has put it, for Beijing, a war over Taiwan could “escalate to the nuclear level against the domestic political consequences of accepting humiliation on the core issue of Chinese nationalism.”40

Freeman’s point is worth dwelling on. Any battle over Taiwan will not just be a question of territorial aggression but a fight over the core conception of modern China’s soul. And for the leaders who launch such an endeavor, their political futures will hinge on the outcome, as will, possibly, their physical safety and that of their families in the event of failure. Under such circumstances, nuclear use might not be palatable, but it could seem far more plausible if military defeat were to equate to loss of domestic power and possible death anyway.

Paul Heer, a former National Intelligence Officer for East Asia, has argued that China is not seeking excuses to invade Taiwan. To the contrary, in his view, Beijing fears action by either Washington or Taipei to alter the status quo thereby forcing China’s hand militarily.41

Given the stakes for any leader who ordered an invasion, such trepidation is understandable. Even with highly favorable conditions, amphibious landings remain among the most complex and risky of all military operations. And current conditions—including the immaturity of China’s anti-submarine warfare (ASW) capabilities,42 its lack of amphibious lift, the capabilities of the U.S. Navy, and the 100-mile width of the Taiwan Strait—cannot be construed as entirely favorable despite other advantages, such as Taiwan’s overall proximity and the general growth in Chinese military power.

On the one hand, this is good news as it discourages the likelihood of an overt attempt by China to capture Taiwan. On the other, it means that should such an operation be dared, all elements of Chinese national power would eventually be on the table, especially if U.S. intervention is forthcoming and proves decisive in the early going. This might be the case even if nuclear use was not seen as a viable option by Chinese leaders at the outset of the campaign. The prospect of catastrophic defeat could change their thinking.

Could the United States resort to nuclear use?

It is also not entirely outside the realm of possibility that the United States could contemplate nuclear use. (Indeed, some of the main advocates for more openly planning to defend Taiwan have also expressed interest in enhancing U.S. tactical nuclear options for Chinese and Russian conflict scenarios.)43 Up to this point, this paper has mainly addressed the notion that the China’s leadership could be panicked into nuclear escalation. But defending Taiwan should not be seen as either an easy or certain victory for the United States. Although China would face important challenges in accomplishing an amphibious landing on the island, U.S. forces would also have to surmount their own difficulties, which include operating in close proximity to the air and missile forces based on the Chinese mainland. In addition, U.S. warfighting efforts could be impeded by unreliable access to some regional bases (such as in the Philippines) and the vulnerability of other bases (such as in Japan) to Chinese conventional missile attacks.44

Nuclear arsenals of the U.S. and China

China’s nuclear arsenal is significantly outnumbered by that of the United States, but it is large enough to inflict significant damage and will expand further over the next decade.

How would the American leadership respond in the event of an unexpected reversal? How would the American public? If, say, China was able to sink a single U.S. aircraft carrier—killing perhaps 5,000 Americans—it would inflict in an afternoon more fatalities than U.S. forces suffered in the eight-year Iraq War. As questionable and costly as its post-9/11 conflicts have been, U.S. forces were never routed in massive numbers. Even Vietnam was considered a slow bleed. And after that war’s end, it was frequently asserted as gospel that U.S. forces were never defeated outright on the battlefield. One has to go back 70-years to the Korean War to find examples of U.S. forces taking massive casualties in a single battle and openly retreating in ignominy. It would be jarring to an American public ensconced in the myth of post-Gulf War military superiority to suffer a sudden loss of thousands of lives on a carrier or other high profile naval asset.

Alternately, if China did use conventionally armed missiles against U.S. bases in Japan and Guam, perhaps killing not only U.S. and Japanese military personnel, but also local civilians and U.S. dependents, what reaction would that spark? Is it so far-fetched to consider the United States initiating nuclear use under those circumstances? The United States does have viable tactical options, which it has sought to make more robust in accordance with the findings of 2018 Nuclear Posture Review (NPR).45 These include the deployment of the submarine-launched low-yield W76-2 warhead and development of an upgraded version of the B61 tactical gravity bomb.46 Chinese observers have expressly noted that these systems could make U.S. nuclear use more likely, a situation compounded by diminishing U.S. conventional superiority in the Western Pacific.47

To be clear, as with all aspects of this discussion, the point is not to state with certainty that the United States would resort to nuclear use. It might not be even likely. But it is worth acknowledging that it is possible. That is the element that needs to be injected into the debate not only over the future of strategic ambiguity, but over defense planning for Taiwan scenarios more broadly.

The preferred U.S. style of warfare—to conduct attacks deep throughout an enemy’s territory rather than simply meeting them at a forward line of engagement—also presents problems and contains the prospect that non-nuclear strikes might unintentionally trip Chinese redlines regarding nuclear use. Within the U.S. academic community, this has produced a small, but important body of literature focused on the subject of “entanglement,” or the co-mingling of systems with both conventional and nuclear applications.48 This discussion has primarily focused on China’s ballistic missile force, as most of its systems are capable of firing both nuclear and non-nuclear warheads.49

China’s increasing reliance on road-mobile ICBMs (such as the DF-31 variants and the new DF-41) complicates this problem, creating the potential for their misidentification as shorter-range systems, such as the road-mobile DF-21 and DF-26, that might be used against U.S. ships or regional bases.50 Analysts have also expressed concern over the potential for U.S. forces to inadvertently sink a Chinese SSBN as part of its ASW campaign during a Taiwan conflict, a fear that echoes similar worries from the U.S.-Soviet struggle.51 Recall again the private comments of Chinese officials about conventional attacks on nuclear systems nullifying its NFU policy.

The potential for mutual miscalculation

Entanglement issues are far from the whole of the problem. There is still a fundamental misreading—perhaps on both sides—of the ability to manage escalation in Taiwan contingencies for reasons beyond strict operational matters. The very fact of China attempting something as complex and challenging as an amphibious invasion of an island of 24 million people would show an unwelcome tolerance for risk. For that matter, U.S. efforts to defend said island—halfway around the world on another nuclear power’s doorstep—also shows a fair amount of audacity. Put differently, the act of aggression against Taiwan and the effort to repel such an attack both demonstrate that each side is willing to take actions which could be viewed as inherently risky.

Through that lens, the additional step to unwanted nuclear escalation is not a great leap. States act rationally, right up until they do not. In considering how a Taiwan contingency would play out, it would therefore be prudent to assume that nuclear use is more viable than cold assessments of each side’s pre-conflict intentions suggest. If academic surveys of Chinese strategic literature are correct, overoptimism on the ability to manage escalation once hostilities commence is not confined to the U.S. side.52

The summation to the issues discussed in this paper is thus not a traditional list of hard policy recommendations but more the urging of a specific mindset moving forward. While all those attempting to think through U.S. policy on Taiwan should be commended for contributing to the debate, the starting and end point for such discussions must be strategic stability between the United States and China. Nuclear issues—more than any other aspect—have to be foremost as the United States reexamines strategic ambiguity and debates defense planning options for Taiwan. To do otherwise is ultimately faulty policymaking.

Endnotes

1 For more on the deployment of U.S. nuclear weapons on and around Taiwan during the Cold War, see Hans Kristensen, “Nukes in the Taiwan Crisis,” Federation of American Scientists, May 13, 2008, https://fas.org/blogs/security/2008/05/nukes-in-the-taiwan-crisis/.

2 President Jimmy Carter notified Taiwan on January 1, 1979, that the U.S. was withdrawing from the treaty, giving the requisite one-year notification of withdrawal called for in the accord. It formally took effect on January 1, 1980.

3 Full text of the Taiwan Relations Act, January 1, 1979, https://www.ait.org.tw/our-relationship/policy-history/key-u-s-foreign-policy-documents-region/taiwan-relations-act/. For a good explication of the U.S. obligations under the TRA, see Julian Ku, “Taiwan’s U.S. Defense Guarantee Is Not Strong, But It Isn’t That Weak Either,” Lawfare, January 15, 2016, https://www.lawfareblog.com/taiwans-us-defense-guarantee-not-strong-it-isnt-weak-either.

4 For example, in the early months of his presidency, President George W. Bush affirmed that the U.S. had an obligation to defend Taiwan and that the U.S. would do “whatever it took” to protect the island. Although his views subsequently moderated and he would later discourage a Taiwanese referendum on independence, at the time, Bush’s comments were interpreted as moving the U.S. further outside strategic ambiguity than at any point since 1979. See David Sanger, “U.S. Would Defend Taiwan Bush Says,” New York Times, April 26, 2001, https://www.nytimes.com/2001/04/26/world/us-would-defend-taiwan-bush-says.html.

5 For an extended discussion of the challenges faced by the Chinese in conducting an amphibious assault, see Michael Beckley, “The Emerging Military Balance in Asia,” International Security 42, no. 2 (Fall 2017): 87–90; Michael Hunzeker and Alexander Lanoszka, A Question of Time: Enhancing Taiwan’s Conventional Deterrence Posture (Arlington, VA: Center for Security Policy Studies, November 2018): 53–57.

6 Office of the Secretary of Defense, “Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China,” Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 2020: 117.

7 For more detailed discussions of strategic bombardment and blockade scenarios, see Beckley, “The Emerging Military Balance in Asia,” 91–95; Hunzeker and Lanoszka, A Question of Time, 50–53.

8 Mike Sweeney, “Assessing Chinese Maritime Power,” Defense Priorities, October 2020, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/assessing-chinese-maritime-power.

9 Richard Haass and David Sacks, “American Support for Taiwan Must Be Unambiguous,” Foreign Affairs, September 2, 2020, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/american-support-taiwan-must-be-unambiguous.

10 Bonnie Glaser and Michael J. Mazarr, “Dire Straits,” Foreign Affairs, September 24, 2020, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2020-09-24/dire-straits.

11 Mark T. Esper, “Secretary of Defense Speech at RAND (As Delivered),” U.S. Department of Defense, September 16, 2020, https://www.defense.gov/Newsroom/Speeches/Speech/Article/2350362/secretary-of-defense-speech-at-rand-as-delivered/.

12 Elbridge Colby and Jim Mitre, “Why the Pentagon Should Focus on Taiwan,” War on the Rocks, October 7, 2020, https://warontherocks.com/2020/10/why-the-pentagon-should-focus-on-taiwan/.

13 In November 2020, Taiwan’s Naval Command publicly announced a deployment on the island by U.S. Marine Raiders before subsequently retracting the statement, which was also disavowed by the Department of Defense. See Abhijnan Rej, “U.S. Marine Raiders Arrive in Taiwan to Train Taiwanese Marines,” Diplomat, November 11, 2020, https://thediplomat.com/2020/11/us-marine-raiders-arrive-in-taiwan-to-train-taiwanese-marines/; Seth Robson, “Pentagon Refutes Reports That Marine Raiders Are Training Forces on Taiwan,” Stars & Stripes, November 10, 2020, https://www.stripes.com/news/pacific/pentagon-refutes-reports-that-marine-raiders-are-training-forces-on-taiwan-1.651679; Thomas Newdick, “Taiwan Issues Rare Confirmation That U.S. Special Operators Are Training on the Island (Updated),” Drive, November 10, 2020, https://www.thedrive.com/the-war-zone/37549/taiwan-issues-rare-confirmation-that-u-s-special-operators-are-training-on-the-island.

14 There have been a few notable exceptions. See, for example, Caitlin Talmadge, “Beijing’s Nuclear Option,” Foreign Affairs, 97, No. 6, (November/December 2018), 44–50, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/china/2018-10-15/beijings-nuclear-option.

15 Estimate of the Chinese nuclear inventory is from Office of the Secretary of Defense, “Annual Report to Congress,” 85. Figures on British and French nuclear holdings taken from Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation: “Fact Sheet: The United Kingdom’s Nuclear Arsenal,” April 22, 2020, https://armscontrolcenter.org/fact-sheet-the-united-kingdoms-nuclear-arsenal/; Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation, “Fact Sheet: France’s Nuclear Arsenal,” March 27, 2020, https://armscontrolcenter.org/fact-sheet-frances-nuclear-arsenal/.

16 Hans M. Kristensen and Matt Korda, “United States Nuclear Forces, 2020,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 76, No. 1, January 13, 2020, 47, https://doi.org/10.1080/00963402.2019.1701286.

17 For more on China’s NFU policy, see Hans. M. Kristensen and Matt Korda, “China’s Nuclear Forces, 2020,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 76, No. 6, December 10, 2020, 447, https://doi.org/10.1080/00963402.2020.1846432; David Santoro and Robert Gromoll, “On the Value of Nuclear Dialogue with China,” Pacific Forum Issue & Insights, 20, No. 1, November 2020, 13–14, https://pacforum.org/publication/issues-insights-vol-20-sr-1-on-the-value-of-nuclear-dialogue-with-china; Gregory Kulacki, “Would China Use Nuclear Weapons First in a War with the United States?” Diplomat, April 27, 2020, https://thediplomat.com/2020/04/would-china-use-nuclear-weapons-first-in-a-war-with-the-united-states/.

18 Fiona S. Cunningham and M. Taylor Fravel, “Dangerous Confidence? Chinese Views on Nuclear Escalation,” International Security, 44, No. 2, (Fall 2019), 83.

19Office of the Secretary of Defense, “Annual Report to Congress,” 86; Santoro and Gromoll, “On the Value of Nuclear Dialogue with China,” 13–14.

20 Office of the Secretary of Defense, “Annual Report to Congress,” 88.

21 Kristensen and Korda, “Chinese Nuclear Forces, 2020,” 447.

22 Office of the Secretary of Defense, “Annual Report to Congress,” 85–87.

23 Regarding the acoustic deficiencies of the Jin-class SSBN, see the chart “Submarine Quieting Trends” in Office of Naval Intelligence, “The People’s Liberation Army Navy: A Modern Navy with Chinese Characteristics,” August 2009, https://fas.org/irp/agency/oni/pla-navy.pdf; Jeffrey Lewis, “How Capable Is the Type 094?” Arms Control Wonk, July 31, 2007, https://www.armscontrolwonk.com/archive/201579/how-capable-is-the-094-23/; Hans M. Kristensen, “China’s Noisy Nuclear Submarines,” Federation of American Scientists, November 21, 2009, https://fas.org/blogs/security/2009/11/subnoise/; Tong Zhao, Tides of Change: China’s Nuclear Ballistic Nuclear Submarines and Strategic Stability, Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2018, 26–27, https://carnegietsinghua.org/2018/10/24/tides-of-change-china-s-nuclear-ballistic-missile-submarines-and-strategic-stability-pub-77490.

24 Office of the Secretary of Defense, “Annual Report to Congress,” 86; Kristensen and Korda, “Chinese Nuclear Forces, 2020,” 448.

25 See chart “Nuclear Ballistic Missiles” in Office of the Secretary of Defense, “Annual Report to Congress,” 58.

26 See chart “Nuclear Ballistic Missiles” in Office of the Secretary of Defense, “Annual Report to Congress,” 58.

27 Office of the Secretary of Defense, “Annual Report to Congress,” 56; Kristensen and Korda, “Chinese Nuclear Forces, 2020,” 448.

28 Office of the Secretary of Defense, “Annual Report to Congress,” 56; Kristensen and Korda, “Chinese Nuclear Forces, 2020,” 448.

29 The figure of 36 DF-31As and 36 DF-31AGs is taken from “Table 1. Chinese Nuclear Forces, 2020,” in Kristensen & Korda, “Chinese Nuclear Forces, 2020,” 444.

30 See Office of the Secretary of Defense, “Annual Report to Congress,” 56, and Kristensen and Korda, “Chinese Nuclear Forces, 2020,” 448.

31 Perhaps the most explicit manifestation of China’s thinking regarding Taiwan is the Anti-Secession Law adopted by the Tenth National People’s Congress in 2005, which essentially bars Taiwan from declaring independence under penalty of force and fully encodes the notion that Taiwan is already Chinese territory proper. For text of the act, see Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in the United States of America, “Anti-Secession Law (Full Text),” March 15, 2005, http://www.china-embassy.org/eng/zt/999999999/t187406.htm.

32 Avery Goldstein, “China’s Grand Strategy Under Xi Jinping,” International Security, 45, no. 1, Summer 2020, 173¬–174.

33 J. Michael Cole, “The Third Taiwan Strait Crisis: The Forgotten Showdown Between China and America,” National Interest, March 10, 2017, https://nationalinterest.org/feature/the-third-taiwan-strait-crisis-the-forgotten-showdown-19742.

34 Goldstein, “China’s Grand Strategy under Xi Jinping,” 187–191.

35 Goldstein, “China’s Grand Strategy under Xi Jinping,” 191.

36 Jessica Chen Weiss, “How Hawkish Is the Chinese Public? Another Look at ‘Rising Nationalism’ and Chinese Foreign Policy,” Journal of Contemporary China, March 2019, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/328260672_How_Hawkish_Is_the_Chinese_Public_Another_Look_at_Rising_Nationalism_and_Chinese_Foreign_Policy.

37 Xi and the CCP have also burnished China’s great-power status for domestic propaganda purposes, raising popular expectations of how China will behave on the world stage. This, too, would complicate any effort to bargain or to settle a conflict over Taiwan short of reunification, once a military campaign is undertaken. See Goldstein, “China’s Grand Strategy under Xi Jinping,” 192–193.

38 Toshi Yoshihara, Dragon Against the Sun: Chinese Views of Japanese Maritime Seapower (Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, 2020), 89, https://csbaonline.org/research/publications/dragon-against-the-sun-chinese-views-of-japanese-seapower.

39 Yoshihara, Dragon Against the Sun, 89.

40 Ambassador Chas W. Freeman, Jr., “War with China Over Taiwan?” Remarks to a Salon of the Committee for the Republic, December 17, 2020, https://chasfreeman.net/war-with-china-over-taiwan/.

41 Paul Heer, “The Inconvenient Truth about Taiwan’s Place in the World,” National Interest, September 27, 2020, https://nationalinterest.org/feature/inconvenient-truth-about-taiwan%E2%80%99s-place-world-169659.

42 Sweeney, “Assessing Chinese Maritime Power,” 4–5.

43Elbridge Colby, “Against the Great Powers: Reflections on Balancing Nuclear and Conventional Power,” Texas National Security Review, 2, No. 1, November 2018, https://tnsr.org/2018/11/against-the-great-powers-reflections-on-balancing-nuclear-and-conventional-power/.

44 For the missile threat to Japanese bases, see, for example, the scenario put forward in Thomas Shugart and Javier Gonzalez, “First Strike: China’s Missile Threat to U.S. Basses in Asia,” Center for New American Security, June 2017, https://s3.amazonaws.com/files.cnas.org/documents/CNASReport-FirstStrike-Final.pdf.

45 See Office of the Secretary of Defense, Nuclear Posture Review, February 2018, 52–55, https://media.defense.gov/2018/Feb/02/2001872886/-1/-1/1/2018-NUCLEAR-POSTURE-REVIEW-FINAL-REPORT.PDF.

46 John Rood, “Statement on the Fielding of the W76-2 Low-Yield Submarine Launched Ballistic Missile Warhead,” U.S. Department of Defense, February 4, 2020, https://www.defense.gov/Newsroom/Releases/Release/Article/2073532/statement-on-the-fielding-of-the-w76-2-low-yieldsubmarine-launched-ballistic-m/, and National Nuclear Security Administration, “B61-12 Life Extension Program,” June 2020, https://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2020/06/f76/B61-12-20200622.pdf.

47 Santoro and Gromoll, “On the Value of Nuclear Dialogue with China,” 8.

48 Caitlin Talmadge, “Would China Go Nuclear? Assessing the Risk of Chinese Nuclear Escalation in a Conventional War with the United States,” International Security, 41, No. 4, Spring 2017, 50–92; David C. Logan, “Are They Reading Schelling in Beijing? The Dimensions, Drivers, and Risks of Nuclear-Conventional Entanglement in China,” Journal of Strategic Studies, November 12, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2020.1844671.

49 Concerns have also been expressed about the possibility of U.S. attacks on China’s command and control networks falling under the rubric of “entanglement,” in so far as these systems might be used to control both conventional missile forces and the nation’s strategic assets. There are some signs that this may not be as great a danger as previously thought, due in part to wide-ranging changes made to China’s military organizational structure beginning in late 2015. As a result of this reorganization, distinct lines of command were established for China’s conventional and nuclear missile forces, with the former apparently embedding in the military’s new regional Theater Commands and the latter running directly from the CMC to the operational units maintained separately by the newly created PLA Rocket Force. From an organizational standpoint, at least, command and control over conventional and nuclear missiles thus seems far more distinct (and presumably less susceptible to entanglement) than prior to 2015 reforms. Entanglement in this area cannot be completely discounted, though, due to inherent uncertainty surrounding China’s precise command arrangements and the question of whether there is overlap between the physical communication systems involved. That said, China has long been aware of the U.S. preference for attacking enemy command and control networks and has taken pains to harden its own systems in this regard. See the discussions in Logan, “Are They Reading Schelling in Beijing?” 25–27, and in Fiona S. Cunningham and M. Taylor Fravel, “Assuring Assured Retaliation: China’s Nuclear Posture and U.S.-China Strategic Stability,” International Security, 40, No. 2, (October 2015), 44–45.

50 Logan, “Are They Reading Schelling in Beijing?” 32.

51 For concerns over the unintentional sinking of a Chinese SSBN by U.S. forces, see Talmadge, “Would China Go Nuclear?” 53–55, 75–77. For a discussion of the original issue of the escalatory impact of the sinking of a Soviet SSBN during a potential conventional war between NATO and the Warsaw Pact, see Barry R. Posen, “Inadvertent Nuclear War? Escalation and NATO’s Northern Flank,” International Security, 7, No. 2, Fall 1982, 28–54.

52 Cunningham and Fravel, “Dangerous Confidence?” 61–109.