U.S. interests in Yemen are narrow and undermined by Saudi Arabia’s intervention

U.S. interests in the Middle East are limited: (1) prevent major, long-term disruptions to the flow of oil and (2) counter anti-U.S. terror threats. In Yemen, threats come primarily from Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), not from the civil war combatants.

Yet President Obama provided, and President Trump continued, support for the Saudi-led coalition, which intervened on behalf of the faction led by Addrahhuh Mansur Hadi, Yemen’s internationally recognized president, against the Houthis.

U.S. military support for the Saudi-led coalition has included the sale of precision-guided munitions, intelligence on Houthi targets, mid-air refueling, and diplomatic backing at the U.N.

U.S. participation in this proxy war prolongs it, exacerbates human suffering, and gives AQAP greater space to operate. Ending U.S. support could help reinvigorate the now-stalled U.N. peace process by encouraging Saudi Arabia to settle.

Lines of control in Yemen

The local conflict between Houthi forces and the recognized Yemeni government gives AQAP room to operate, undercutting the narrow U.S. counterterrorism goal in that country.

Support for the Saudi-led war undermines U.S. interests and values

Saudi Arabia views its intervention as aiding its domestic security and combating Iran’s influence—neither is a vital U.S. interest.

Saudi Arabia is a major oil supplier and at times assists the U.S. on counterterrorism. But it sells oil and counters terrorists out of self-interest—not as a favor to the U.S.—and there is no evidence it will stop when the U.S. exits the Yemen conflict.

Saudi airstrikes consistently kill civilians. Aiding the Saudis is an affront to U.S. values and, on balance, bad for U.S. interests because it generates resentment from Yemenis that could lead to harmful consequences including terrorism.

Iran’s involvement in Yemen pre-dates Saudi Arabia’s 2015 intervention, but it supports the Houthis with arms today to bleed the kingdom at low cost. Its control over Houthi forces is limited.

Protecting Saudi Arabia from the consequences of its mistaken intervention is not a sound rationale for U.S. military support, which gives the kingdom the confidence to perpetuate a stalemated war and brings Iran and the Houthis closer together.

While AQAP is still regularly targeted by U.S. drone strikes, the civil war aids the group with recruitment and provides operation space. AQAP is concentrated in the south, in areas nominally control by pro-Saudi Hadi forces.

Reports the U.S. could designate the Houthis as terrorists seem to be a sop to the Saudis with no benefit to the U.S. The designation would complicate humanitarian aid but would not meaningfully affect the balance of power or peace negotiations.

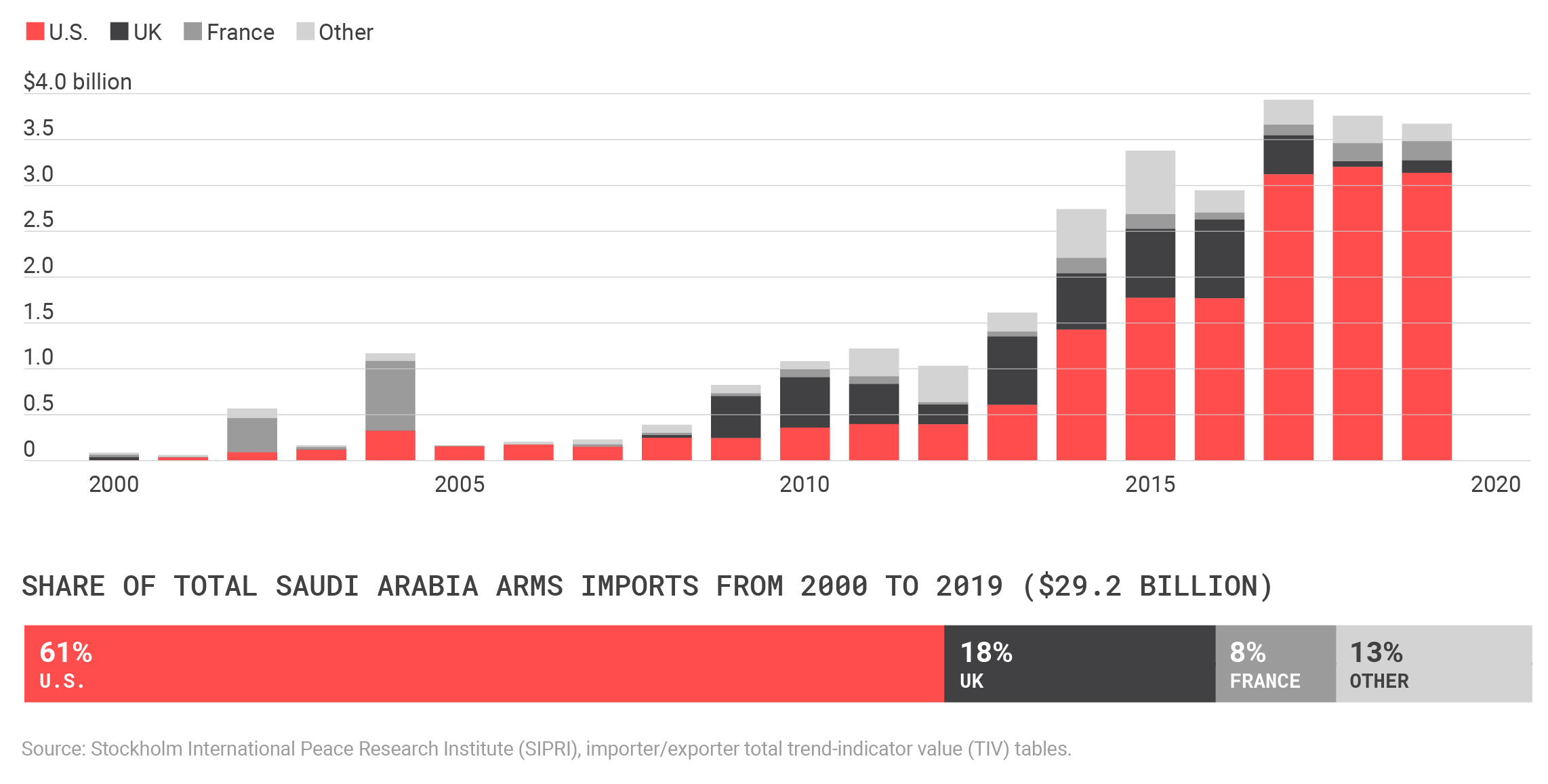

Arms suppliers to Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia has become the largest importer of arms in the world, and the U.S. is its biggest supplier.

Reevaluate drone strikes

Since 2009, well before Saudi Arabia’s intervention, the U.S. has conducted more than 300 airstrikes (mostly by drone) and a few ground raids against AQAP, killing more than 1,200 militants and hundreds of civilians.

With the onset of Yemen’s civil war, chaotic conditions allowed AQAP to grow its ranks and even hold territory, while embedded within local tribal structures. The Houthis violently oppose the primary U.S. enemy in Yemen, AQAP.

The U.S. responded with increased strikes, especially after the Trump administration loosened rules of engagement in 2017. Strikes have lately slowed to a near halt.

While drone strikes can disrupt terrorist operations, they can also create a self-perpetuating cycle by (1) creating enemies as locally focused militants turn their attention more toward the distant enemy attacking them and (2) creating bureaucratic processes which continue to generate targets as a matter of course.

It is difficult to evaluate the effectiveness of drone strikes without more public information, but it makes sense to pause strikes and subject them to exacting oversight to determine whether their counterterrorism benefit justifies their various costs.

A settlement of the civil war would aid stability and efforts to deal with tribal rulers who make AQAP operations even more difficult—that is a local counterterrorism solution not reliant on continual U.S. airstrikes.

Recalibrate the U.S.-Saudi relationship

Yemen is the world’s worst humanitarian crisis. More than 100,000 civilians have been killed, and 80 percent of the population requires humanitarian aid. Many Yemenis hold the U.S. responsible for its role in the death and destruction perpetrated by Saudi Arabia.

U.S. interests and values both call for exiting the conflict and ending all support for the Saudi-UAE campaign—including the sale and operation of offensive weaponry.

Ending support would encourage the Saudis to unwind the counterproductive intervention, boost the U.N.-led peace process, and pressure the parties to negotiate a settlement.

The kingdom is not an ally and does not deserve unconditional support. The U.S. should cooperate with Saudi Arabia where our interests align and recognize where our interests diverge: its war in Yemen and sectarian rivalry with Iran.

The U.S. should treat Saudi Arabia like other authoritarian states—preserving trade and maintaining productive diplomatic relations while being critical of its illiberal practices.