Key points

In 2021, the U.K., France, and Germany deployed 21 naval ships to the Indo-Pacific with a stated aim of helping the U.S. shoulder the burden of collective security and sustaining the “rules-based international order.”

Naval deployments by the U.K., France, and Germany are symbolic and unlikely to affect the balance of power in Asia.

A European pivot to the Indo-Pacific draws scarce attention and resources away from defense issues in Europe.

Instead of encouraging Asian forays, the U.S. should encourage its European allies to assume primary responsibility for European security, freeing the United States to focus on the Pacific, if needed.

Europe pivots to the Indo-Pacific with naval patrols

Major European powers are increasing their naval deployments in the Indo-Pacific, an area stretching from the east coast of Africa to the western Pacific. In the last three years, France, Germany, and even the European Union have issued Indo-Pacific strategies, following the model of the United States.1 Last year alone, three of Europe’s biggest powers—the United Kingdom, France, and Germany—backed these strategies and sailed 21 naval ships to the Indo-Pacific to show maritime presence.2 What unifies these recent developments is their loud support for the “rules-based international order” and for the U.S.-run freedom of navigation operations meant to reassure regional partners and contest China’s expansive territorial claims.3

The United States has for years demanded greater burden sharing from its European allies. However, the past two administrations in Washington have directed these demands toward the Chinese threat to the “rules-based international order,” incentivizing European allies to show symbolic support for this ill-defined mission with flashy naval deployments. But European naval patrols in the Indo-Pacific do not correct the imbalance in alliance burden-sharing in Europe, because of the low deterrence value of naval presence missions and the inefficiency of European power projection at that distance. It also distracts from building a common front in Europe against Russia, the only real threat to European states’ territorial integrity.

From the standpoint of U.S. security interests, the greatest contribution the United Kingdom, France, and Germany can make is to assume greater responsibility for balancing Russia and deterring its aggression, along with the rest of the European allies, freeing the United States to prioritize the Pacific. By failing to correct its overextension, the United States not only expends limited resources, but also risks defaulting on competing security commitments.

NATO-Europe should devote its military resources, not toward Asia, but where its interests and advantages are greatest: Europe.

United Kingdom Indo-Pacific activity

The United Kingdom’s first military foray into the Pacific after a five-year hiatus came in the summer of 2018.4 The Royal Navy’s HMS Albion, an amphibious transport dock, sailed close to the Paracel Islands in the South China Sea, which China claims as its own.5

In May 2021, the United Kingdom dispatched a carrier strike group led by the HMS Queen Elizabeth with an escort, including the American destroyer USS The Sullivans and Dutch ship HNLMS Evertsen, on a 26,000-mile mission to the western Pacific. The British government hailed the aircraft carrier’s maiden deployment as the largest concentration of maritime power to leave the United Kingdom in 20 years.6 It left from Portsmouth in England; went through the Strait of Gibraltar, Mediterranean Sea, and Suez Canal; then sailed into the Indian and Pacific oceans.

According to British Prime Minister Boris Johnson, the goal of the mission was to “demonstrate our interoperability with allies and partners—in particular the United States—and our ability to project cutting-edge military power in support of NATO and international maritime security.”7 The carrier strike group sailed through the South China Sea in July, and in September, the frigate HMS Richmond detached from the group to sail through the Taiwan Strait, the first British warship to do so since 2008.

The United Kingdom also sent two offshore patrol vessels to the Indo-Pacific in September 2021. They will rotate between friendly ports for “at least the next five years.” The Royal Navy is planning to replace these combat patrol ships with two frigates by 2030.8

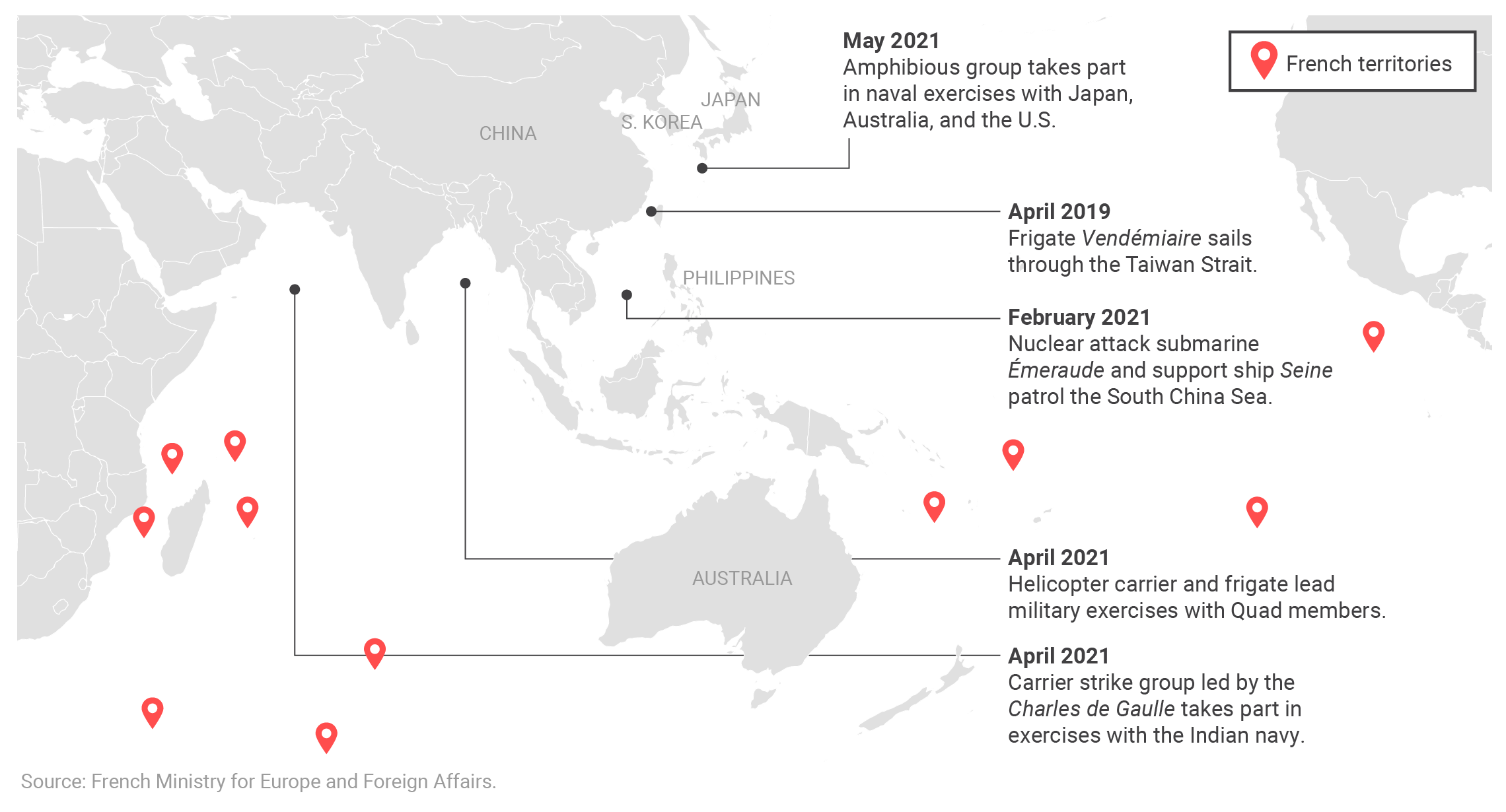

French expeditions in Asia

France, the only European power with significant territorial holdings in Asia, was the first to lay out its strategy for the Indo-Pacific during French President Emmanuel Macron’s visit to Australia in May 2018. More than 1.6 million French citizens live in the Indo-Pacific, spread between the territories of Réunion and Mayotte in the South Indian Ocean and New Caledonia and French Polynesia in the Pacific. These make up more than 90 percent of France’s global exclusive economic zones, rich with mineral and fishing resources.

According to the French Indo-Pacific strategy, France’s forward presence—including 8,000 military personnel divided between the South Indian Ocean territories, New Caledonia, and French Polynesia—is there to protect its overseas territories and economic resources and to serve as a base for joint military exercises with partners.9 However, starting around 2014, France’s military deployments there increasingly focus on ensuring freedom of navigation in the waters claimed by China—thousands of miles away from French territories.

In April 2019, the French frigate Vendémiaire sailed through the Taiwan Strait, provoking a harsh rebuke from Beijing.10 In February 2021, the French defense minister revealed a French nuclear-propelled attack submarine, the SNA Émeraude, completed a patrol in the South China Sea, crowning a seven-month deployment to the region.11 The same month, France sent the landing helicopter carrier FS Tonnerre and frigate Surcouf on a three-month mission that culminated in a joint exercise with the Japanese and U.S. navies off the coast of Kagoshima in May.12 To increase interoperability between France and its Indo-Pacific partners, the two warships also took part in the Perouse 21 naval exercise in the Bay of Bengal, a third iteration of the annual event that for the first time saw the Indian navy’s participation.13 Over the course of the deployment, the amphibious group crossed the South China Sea twice. France also sent its carrier strike group led by the Charles de Gaulle, France’s only aircraft carrier, to the Indian Ocean in February 2021 where it participated in the Veruna 21 naval exercise in the Indian Ocean.

French territories and recent naval operations in the Indo-Pacific

While France has several territories in the Indo-Pacific, its recent naval patrols and military exercises have mirrored U.S. operations near China.

German frigate deployment

Unlike the United Kingdom and France, Germany has neither overseas territories nor ambitions to maintain a global military footprint. Nevertheless, in a gesture widely seen as a break from its postwar pacifist tradition, in August 2021, Germany sent the frigate Bayern on a six-month deployment to Japan, the German navy’s first in 20 years.14 The frigate participated in NATO’s Sea Guardian exercise in the Mediterranean Sea before sailing on, through the Suez Canal, to the Indian and Pacific Oceans. Its stops included Australia, Japan, South Korea, Singapore, and Vietnam. The Bayern passed through the South China Sea in December 2021 before traveling to Singapore and Vietnam.

There is no concrete plan for a permanent German presence in the Indo-Pacific. But following the arrival of the Bayern in Japan in November 2021, the then-chief of the German navy, Vice Adm. Kay-Achim Schönbach, expressed hope German warships would deploy to the region every two years, beginning in 2023.15 Germany also committed to send six Eurofighter jets and other aircraft to take part in Australia’s Pitch Black biennial military exercise in September 2022, in what the German Air Force Chief of Staff Lt. Gen. Ingo Gerhartz called the “first and biggest deployment” to the Indo-Pacific by the Luftwaffe.16

The route of the German frigate Bayern

German officials talk about Germany’s first major naval operation in the Indo-Pacific in 20 years as a new prioritization of the region, with more operations to follow.

A gesture toward Washington

What explains this newfound interest of the United Kingdom, France, and Germany in the Indo-Pacific and the apparent enforcement of freedom of navigation half a world away from Europe? First, the United States has urged European allies to contribute more to NATO’s collective defense, sometimes warning a failure to do so would undermine U.S. security commitment to Europe. At the same time, the United States has singled out China as the greatest threat to its own security, and thus, by extension, a serious threat to the “international order.”

During the NATO foreign ministerial in April 2019, at the urging of then-Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, NATO members initiated a reassessment of the emerging threat of China.17 This internal review concluded with NATO leaders, for the first time, discussing the security consequences of China’s rise for NATO at the London Summit in December 2019.18 Throughout 2020, the Trump administration insisted European countries follow its more confrontational line on China, pressuring the British government to cut the Chinese telecoms giant Huawei out of its 5G network infrastructure, implying a failure to do so would undermine intelligence sharing with the United States.

Since President Joe Biden assumed office in January 2021, the United States has continued to advocate for greater NATO action against China under the banner of assembling democracies in a global fight against authoritarianism. In February 2021, President Biden argued democracies needed to prepare for a “long-term strategic competition with China,” and that the United States, Europe, and Asia must rally together to defend our “shared values and advance our prosperity across the Pacific.”19 At the NATO Summit in Brussels in June 2021, NATO leaders elevated the rise of China to a “systemic challenge” that required closer cooperation with Asia-Pacific democracies Australia, Japan, New Zealand, and South Korea in support of the “rules-based international order.”20

Responding to this call by two U.S. administrations, major European powers have intensified partnerships with regional democracies threatened by China and sent warships through disputed waters. Naval presence missions are a low-cost, high-visibility way of convincing the United States that European allies are sharing the burden of collective security by playing into Washington’s framing of a global competition with China. By insisting NATO take an active part in security competition with China, the United States incentivizes European allies to chip in token military contributions in the Indo-Pacific, often instead of committing more attention and resources toward defending their own neighborhood.

The post-Brexit United Kingdom is racing ahead of other NATO allies to demonstrate to the United States that it remains a valuable ally, even as the United States shifts its attention to the Indo-Pacific to confront China. In March 2021, the United Kingdom published its Integrated Review, which proclaimed the nation’s “tilt to the Indo-Pacific,” a term that echoes the United States’ own “pivot to Asia.”21 The document predicts that the United States will “continue to ask more from its allies in Europe in sharing the burden of collective security.”22 Despite acknowledging that Russia will remain the most “acute threat” to the United Kingdom, the document focuses on the Indo-Pacific, promising that the United Kingdom will be “the European partner with the broadest, most integrated presence” in the Indo-Pacific by 2030.

Germany’s deployment of the frigate Bayern to the Indo-Pacific stemmed from a similar desire to prove useful to the United States—something Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer, when she was the German minister of defense, expressed on the eve of the 2020 U.S. presidential election. The German defense minister said that if Germany was to successfully continue the policy of binding German security to the United States (Westbindung), it had to demonstrate to the future administration in Washington that it is prepared to help the United States shoulder the burden of being a “regulatory power.”23

The first German frigate to sail to Japan in 20 years was intended as a sign of German military commitment to upholding the “rules-based multilateral order” in the Indo-Pacific as well as an example of “solidarity” with partners in the region.24 However, the German government was careful not to antagonize China with the frigate, choosing a path around the Taiwan Strait and even requesting a port call in Shanghai before entering the South China Sea on the frigate’s way back to Germany. The request was denied.25

The French case is unique, given France’s overseas territories and hence stronger interests in the region.26 Even so, France does not articulate its interest in the region in terms of defending its overseas territories from the threat of Chinese aggression. Rather, France is concerned with charting its own course as an alternative security provider to regional powers wishing to retain some latitude in an environment increasingly polarized by Sino-American tensions. India, which is emerging as the cornerstone of the French engagement in the Indo-Pacific, was the number one buyer of French arms between 2016 and 2020, accounting for over one-fifth of France’s total sales.27

The French approach may become less tenable as the security competition between the United States and China intensifies. Recently, Australia’s decision to risk its relationship with France by dropping its contract to purchase 12 diesel-powered submarines from Paris to instead partner with the United States in building nuclear-powered submarines showed the French security alternative may not be appealing enough for countries hedging against Chinese aggression. Nevertheless, since the AUKUS deal, President Macron has met with the leaders of India, Indonesia, and South Korea, as well as announced enhanced French cooperation with India through greater intelligence sharing and new bilateral initiatives in “maritime, space, and cyber domains.”28 France is likely to further increase its military presence in the Indo-Pacific to position itself as a player in an area of global economic significance.

Europe should focus on Europe: A division of labor suited to U.S. interests

European forays into the Indo-Pacific do not help the United States, but they do weaken NATO’s ability to defend Europe.

Low deterrence value of naval presence missions

Naval presence missions in the Indo-Pacific are not a good indicator of European willingness to fight a shooting war with China. The United States sails dozens of warships through the Taiwan Strait and the South China Sea each year to contest China’s maritime claims. But the deterrent value of these freedom-of-navigation operations on Chinese behavior, beyond routinely provoking a flurry of heated statements from Beijing, is negligible.

Beijing has not rescinded any of its territorial claims or backed away from upgrading military infrastructure on archipelagos such as the Spratly Islands where a United States destroyer just sailed within 12 nautical miles of the Chinese-occupied Mischief Reef last September. The United States may challenge Chinese legal claims to sovereignty over these reefs but risking military confrontation with another nuclear power over them is another matter. Likewise, both France and the United Kingdom have provoked criticism from Beijing sending their warships through the Taiwan Strait, but China has not deemed these transits threatening enough to respond with more than diplomatic formalities. European patrols do not alter the balance of power or aid deterrence in East Asia.29

Any indication European states are interested in joining a potential war against China is undercut by their leaders’ open skepticism of the threat China poses to NATO. At the NATO Brussels Summit in June 2021, President Macron said bluntly, “NATO is an organization that concerns the North Atlantic, China has little to do with the North Atlantic.”30 President Macron has argued before that China is not a military challenge to NATO and building a coalition against China would be needlessly hostile. When she was the chancellor of Germany, Angela Merkel warned NATO should not overstate the importance of the Indo-Pacific to its collective security. She emphasized instead, “Russia, above all, is the major challenge” for NATO.31

European publics also seem to recognize that while China poses challenges, NATO cannot or should not address them. In a German Marshall Fund poll conducted in April 2021, among 11 NATO members, only 15 percent of respondents believed China to be an important issue for the trans-Atlantic alliance.32 The low threat perception of China among NATO members casts further doubts on the deterrence and reassurance value of naval missions.

Global power projection is costly and inefficient

European allies can more efficiently and effectively defend their own backyard than project power across the globe. Military spending involves tradeoffs. France and Britain could pay for a second and third aircraft carrier, along with naval auxiliaries including fleet-replenishment oilers to enable long-distance naval operations in Asia. Alternatively, they could address gaping shortfalls in military capabilities, like strategic airlift to allow their brigades to deploy at a moment’s notice to reinforce NATO’s eastern flank in case of Russian aggression.33

Assuming the United Kingdom, France, and Germany would be willing to support the United States in a war on the Pacific, they would need to overcome the logistical hurdles of moving the military assets to a distant theater in a short time. To improve response time, Europeans would have to permanently station more warships and combat aircraft in the Indo-Pacific, making use of the French territories, for example, redirecting sea and airpower away from home. Meanwhile, long-awaited improvements in military mobility in Europe, such as upgrading ground infrastructure, roads, and railways to enable NATO tanks and artillery to move swiftly across the continent would likely lose out in European defense budgets.

Even with the costly adjustments in military spending and force posture to acquire global power projection capabilities, the few dozen warships Europeans could collectively marshal would change little about the balance of power in a possible conflict scenario with China. In a war on Taiwan, China could bring to bear most of its 355-vessel navy and potentially hundreds more civilian ships, fighting within the range of missile batteries on the Chinese mainland.34 If the United States wants more help against China, it can start with local allies and focus on bolstering their defensive anti-access area denial (A2/AD) capabilities to impose costs on Chinese aggression without getting drawn into a potentially nuclear war.35

Europe’s major powers can balance against Russia

Any European contribution, whether in deterring or fighting China in the Indo-Pacific, is not likely to offset the effort the United States expends on defending Europe. The reason for the dominant U.S. role in European security institutions has been to prevent a hostile power from overrunning enough of the continent to pose a threat to the United States. In contrast to their relative insignificance in the Indo-Pacific, the three main European powers jointly have the economic potential and political clout in key European institutions to lead the effort of building collective defense capable of deterring Russia.36 The United Kingdom, France, and Germany assuming the responsibility for the conventional aspect of European defense would serve the United States, as the U.S. military shifts focus to Asia. A better division of labor within NATO would also ensure the security architecture in Europe reflects the threats Europeans perceive, not those the United States decides for them.

Russia is the only plausible threat to the territorial integrity of Europe. The Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014 and the war in eastern Ukraine resulted in a sustained increase in military spending in Europe’s major powers. The United Kingdom has increased its annual military spending by 13 percent in real terms since 2014, France by 16 percent, and Germany by 37 percent.37 Major European powers can spend even more if they perceive Russia to be threatening enough, but their combined military spending already exceeds Russia’s.

Even with spending increases, however, European militaries face readiness challenges that will require political attention and coordination. Germany still must address chronic equipment and staffing shortages. Twenty percent of its military personnel positions above the junior level remain vacant.38 Only a little more than half of France’s military aircraft are combat-ready—the “Achilles’ heel” of the French armed forces, according to the French defense minister, Florence Parly.39 Combat readiness is a problem that affects other branches of the French military, too, owing in part to France’s extended global posture from the Sahel to the Pacific. The pursuit of global power projection capabilities in the Indo-Pacific, especially if it increases, will distract from creating a conventional force calibrated to the task of deterring Russia in coalition with other European partners.

Comparison of Europe’s major powers and Russia’s economies and military spending

Europe’s major powers present a formidable balance against Russia; when other European countries join with them (even excluding the U.S.) their advantage is substantial.

Another critical missing piece of collective European defense is interoperability between national militaries that would allow for rapid deployment of coalition forces to areas of conflict, such as northeastern Europe. Rather than devoting more attention to achieving interoperability in naval operations with partners such as Japan, India, and Australia, European powers should integrate their militaries with the overarching goal of defeating Russia in a high-intensity conflict.40

NATO should defend Europe, not the rules-based international order

The United States should not encourage European deployments to the Indo-Pacific—it should abandon the rhetoric that NATO must uphold global rules.41 Instead, the United States should put a renewed emphasis on the original purpose of the trans-Atlantic alliance: defending Europe. The Russian force of more than 150,000 soldiers mobilized on the border with Ukraine amid escalating tensions with NATO is a forceful reminder that large-scale conventional conflict on the European continent is a possible scenario, even for nations, unlike Ukraine, with a security guarantee from the United States.42

At the upcoming NATO summit in Madrid in June 2022, NATO leaders will approve a new Strategic Concept identifying the security priorities of the alliance for the upcoming decade and the military means to implement them. The Biden administration should stress that the divergent security environments and priorities of the United States and Europe are best served by a smarter division of labor, one that is not possible without European powers eventually taking over responsibility for the defense of the continent. The United States should push for the Strategic Concept to include an actionable and time-constrained plan for European members to increase their military interoperability.

Thus, a nebulous goal such as upholding the “rules-based international order” outside of the North Atlantic area should yield to the tangible objective of building a conventional deterrent against Russia. At the same time, Washington should reverse the long-running trend of the United States suppressing initiatives by European powers to bolster their collective security outside of NATO.43 The goal of the United States should not be the preservation of NATO as the only forum for trans-Atlantic security cooperation, but rather the cultivation of strong, independent partners that can respond to security threats in their own neighborhood, while the United States increasingly concentrates on rebuilding at home and advancing its interests in Asia.

Endnotes

1 “The Indo-Pacific Region: A priority for France,” Ministry of European and Foreign Affairs, Government of France, accessed December 2021, https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/en/country-files/asia-and-oceania/the-indo-pacific-region-a-priority-for-france/; “Policy Guidelines for the Indo-Pacific,” Federal Government of Germany, accessed December 2021, https://www.auswaertiges-amt.de/blob/2380514/f9784f7e3b3fa1bd7c5446d274a4169e/200901-indo-pazifik-leitlinien--1--data.pdf; “Joint Communication on the Indo-Pacific,” High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy of the European Commission, September 16, 2021, https://eeas.europa.eu/headquarters/headquarters-homepage/104126/joint-communication-indo-pacific_en.

2 The United Kingdom sent two 2 offshore patrol vessels to the Indo-Pacific, HMS Tamar and HMS Spey; the Carrier Strike Group 2021 led by HMS Queen Elizabeth with 7 British escorts (not counting two allied escort vessels, American and Danish). The French total includes the Amphibious Ready Group made up of landing helicopter dock FS Tonnerre and frigate Surcouf, the carrier strike group led by the Charles de Gaulle with 5 French escorts (not counting 3 allied vessels, American, Greek, and Belgian escorts), as well as the nuclear attack submarine Émeraude and the Offshore Support and Assistance Vessel Seine. Germany sent the frigate Bayern.

3 All three European powers in their strategic documents justify increasing maritime presence in the Indo-Pacific in terms of upholding global rules even if they differ slightly in their language. The Boris Johnson administration wrote in the Integrated Review that HMS Queen Elizabeth deployment in 2021 would “support norm and laws in the region.” France’s Indo-Pacific strategy envisions increased maritime presence in the Indo-Pacific to “ensure freedom of navigation and overflight.” Lastly, the German policy guidelines for the Indo-Pacific state that Germany is prepared to increase maritime presence to “protect and safeguard the rules-based international order in the Indo-Pacific.” See “Global Britain in a Competitive Age, the Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development, and Foreign Policy,” Government of the United Kingdom, March 16, 2021, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/global-britain-in-a-competitive-age-the-integrated-review-of-security-defence-development-and-foreign-policy; “The Indo-Pacific Region: A priority for France,” Ministry of European and Foreign Affairs, Government of France; “Policy Guidelines for the Indo-Pacific,” Federal Government of Germany.

4 Louisa Brooke-Holland, “Royal Navy: A Return to the Far East?” House of Commons Library, U.K. Parliament, May 24, 2018, https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/royal-navy-a-return-to-the-far-east/.

5 “British Navy’s HMS Albion Warned over South China Sea ‘Provocation,’” BBC, September 6, 2018, https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-45433153.

6 “Press Release: Carrier Strike Group Sets Sail on Seven-Month Maiden Deployment,” Government of the United Kingdom, May 22, 2021, https://www.gov.uk/government/news/carrier-strike-group-sets-sail-on-seven-month-maiden-deployment--2.

7 “Global Britain in a Competitive Age,” Government of the United Kingdom.

8 Ben Barry, “Posturing and Presence: The United Kingdom and France in the Indo-Pacific,” Military Balance Blog, International Institute for Strategic Studies, June 11, 2021, https://www.iiss.org/blogs/military-balance/2021/06/france-uk-indo-pacific.

9 “The Indo-Pacific Region: A Priority for France,” French Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs, accessed December 2021, https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/en/country-files/asia-and-oceania/the-indo-pacific-region-a-priority-for-france/.

10 “Exclusive: In Rare Move, French Warship Passes through Taiwan Strait,” Reuters, April 29, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-taiwan-france-warship-china-exclusive/exclusive-in-rare-move-french-warship-passes-through-taiwan-strait-idUSKCN1S10Q7.

11 Sébastian Seibt, “France Wades into the South China Sea with a Nuclear Attack Submarine,” France 24, February 12, 2021, https://www.france24.com/en/france/20210212-france-wades-into-the-south-china-sea-with-a-nuclear-attack-submarine.

12 Xavier Vavasseur, “French Amphibious Ready Group Set Sails for the Indo-Pacific,” Naval News, February 18, 2021, https://www.navalnews.com/naval-news/2021/02/french-amphibious-ready-group-set-sails-for-the-indo-pacific/.

13 Xavier Vavasseur, “Australia, France, India, Japan, and the United States Take Part in Exercise La Pérouse,” Naval News, April 6, 2021, https://www.navalnews.com/naval-news/2021/04/australia-france-india-japan-and-the-united-states-take-part-in-exercise-la-perouse/.

14 “Policy Guidelines for the Indo-Pacific,” Federal Government of Germany.

15 “German Navy Looks to Send Vessels to Indo-Pacific Every Two Years,” Japan Times, November 7, 2021, https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2021/11/07/asia-pacific/german-navy-indo-pacific/.

16 Vivienne Machi, “As Europe looks to the Indo-Pacific, so does the Luftwaffe,” Defense News, November 5, 2021, https://www.defensenews.com/digital-show-dailies/feindef/2021/11/05/as-europe-looks-to-the-indo-pacific-so-does-the-luftwaffe/.

17 Lesley Wroughton and David Brunnstrom, “Pompeo Calls on NATO to Adapt to New Threats from Russia, China,” Reuters, April 4, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-nato/pompeo-calls-on-nato-to-adapt-to-new-threats-from-russia-china-idUSKCN1RG1JZ; Fabrice Pothier, “How Should NATO Respond to China’s Growing Power?” International Institute for Strategic Studies, September 12, 2019, https://www.iiss.org/blogs/analysis/2019/09/nato-respond-china-power.

18 “NATO Recognizes China ‘Challenges’ for the First Time,” Deutsche Welle, December 3, 2019, https://www.dw.com/en/nato-recognizes-china-challenges-for-the-first-time/a-51519351.

19 “Remarks by President Biden at the 2021 Virtual Munich Security Conference,” White House, February 19, 2021, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/speeches-remarks/2021/02/19/remarks-by-president-biden-at-the-2021-virtual-munich-security-conference/.

20 “Brussels Summit Communiqué,” NATO, June 14, 2021, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/news_185000.htm.

21 “Global Britain in a Competitive Age,” Government of the United Kingdom.

22 “Global Britain in a Competitive Age,” Government of the United Kingdom.

23 “Speech by Federal Minister of Defense Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer on the Occasion of the Presentation of the Steuben Schurz Media Award,” Federal Ministry for Defense (Germany), October 23, 2020, https://nato.diplo.de/blob/2409698/75266e6a100b6e35895f431c3ae66c6d/20201023-rede-akk-medienpreis-data.pdf.

24 A. Kramp-Karrenbauer (@akk), “Gemeinsam mit unseren Wertepartnern in der Region zeigt Deutschland mit der Fregatte „Bayern“ Präsenz im #Indopazifik und setzt ein Zeichen der Solidarität. 3/3,” Twitter, August 2, 2021, https://twitter.com/akk/status/1422095744798953472.

25 Bastian Giegerich, “Germany Must End the Confusion over Security and Defence,” Financial Times, August 19, 2021, https://www.ft.com/content/9c93225c-4b63-4a6b-8700-d590dc882a50.

26 “France’s Indo-Pacific Strategy,” Government of France.

27 Pieter D. Wezeman, Alexandra Kuimova and Siemon T. Wezeman, “Trends in International Arms Transfers, 2020,” Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, March 2021, https://sipri.org/sites/default/files/2021-03/fs_2103_at_2020.pdf.

28 “India, France to Expand Defence, Maritime Security Partnership,” Tribune (India), November 7, 2021, https://www.tribuneindia.com/news/nation/india-france-to-expand-defence-maritime-security-partnership-334813.

29 Erik Gartzke and Jon Lindsay, “Strategic Tradeoffs in U.S. Naval Force Structure—Rule the Waves or Wave the Flag?” War on the Rocks, March 1, 2021, https://warontherocks.com/2021/03/strategic-tradeoffs-in-u-s-naval-force-structure-rule-the-waves-or-wave-the-flag/.

30 David M. Herszenhorn and Rym Momtaz, “NATO Leaders See Rising Threats from China, but Not Eye to Eye with Each Other,” Politico, June 14, 2021, https://www.politico.eu/article/nato-leaders-see-rising-threats-from-china-but-not-eye-to-eye-with-each-other/.

31 “As It Happened: NATO Summit,” Politico, June 13, 2021, https://www.politico.eu/article/live-blog-nato-eu-us-summit-joe-biden-jens-stoltenberg-russia-china-cybersecurity/.

32 “Transatlantic Trends 2021,” German Marshall Fund, June 7, 2021, https://www.gmfus.org/news/transatlantic-trends-2021.

33 Hugo Decis, “European Naval Auxiliaries: Heading for Replenishment at Last,” International Institute for Strategic Studies, August 20, 2021, https://www.iiss.org/blogs/military-balance/2021/08/european-naval-auxiliaries.

35 Eugene Gholz, Benjamin Friedman, and Enea Gjoza, “Defensive Defense: A Better Way to Protect U.S. Allies in Asia,” Washington Quarterly vol. 42, no. 4 (2019): 171–189, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/0163660X.2019.1693103.

36 Barry R. Posen, “Europe Can Defend Itself,” Survival vol. 62, no. 6 (2020): 7–34, https://doi.org/10.1080/00396338.2020.1851080.

37 “Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2014-2021),” NATO, June 11, 2021, https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/2021/6/pdf/210611-pr-2021-094-en.pdf.

38 “Information from the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Armed Forces¬—Annual Report 2020 (62nd Report),” German Bundestag, February 23, 2021, https://www.bundestag.de/resource/blob/839328/e1a864120697c27057534944ceb20111/annual_report_2020_62nd_report-data.pdf.

39 Stephanie Pezard, Michael Shurkin, and David Ochmanek, “A Strong Ally Stretched Thin—An Overview of France's Defense Capabilities from a Burdensharing Perspective,” RAND Corporation, 2021, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA231-1.html.

40 Interoperability is lacking both on the defense industrial level as well as the operational level. For example, European states operate 17 different types of main battle tanks, compared to just one (M1 Abrams) in the United States. Moreover, despite military budget increases, the United Kingdom seems to be giving up on the capability to fight a peer adversary such as Russia in a high-intensity conflict, reducing its number of armored infantry brigades from 3 to only 1 by 2025. “Reflection Paper on the Future of European Defense,” accessed February 2022, https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/reflection-paper-defence_en.pdf. On the United Kingdom’s plans to lighten its only warfighting division, see https://www.iiss.org/blogs/military-balance/2021/01/british-army-heavy-division.

41 “U.S. Calls German Warship's Plan to Sail South China Sea Support for Rules-Based Order,” Reuters, March 3, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-southchinasea-germany-usa-idUSKCN2AW016.

42 Sascha Glaeser, “The Futility of U.S. Military Aid and NATO Aspirations for Ukraine,” Defense Priorities, November 15, 2021, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/the-futility-of-us-military-aid-and-nato-aspirations-for-ukraine.

43 Hans Binnendijk and Alexander Vershbow, “Needed: A Trans-Atlantic Agreement on European Strategic Autonomy,” Defense News, October 10, 2021, https://www.defensenews.com/global/europe/2021/10/10/needed-a-transatlantic-agreement-on-european-strategic-autonomy.