Key points

The Middle East is a small, poor, weak region beset by an array of problems that mostly do not affect Americans—and that U.S. forces cannot fix. The best thing the U.S. can do is leave.

The immense cost and evident fruitlessness of U.S. wars in the Middle East are widely lamented in American politics, but not enough to extricate U.S. troops. And even beyond the wars, U.S. policy in the region is an expensive and unnecessary disaster.

The cost of maintaining forces to protect the Middle East from itself is extraordinary, even in peacetime. Conservatively, attempting to control the Middle East costs Americans on the order of $65–70 billion each year, apart from the trillions spent on wars there. The number should be closer to zero.

Nothing about the Middle East warrants the U.S. investment there over the past 30 years. The few important interests there—preventing major terrorist attacks, stopping the emergence of a market-making oil hegemon, curbing nuclear proliferation, and ensuring no regional actor destroys Israel—do not require American troops.

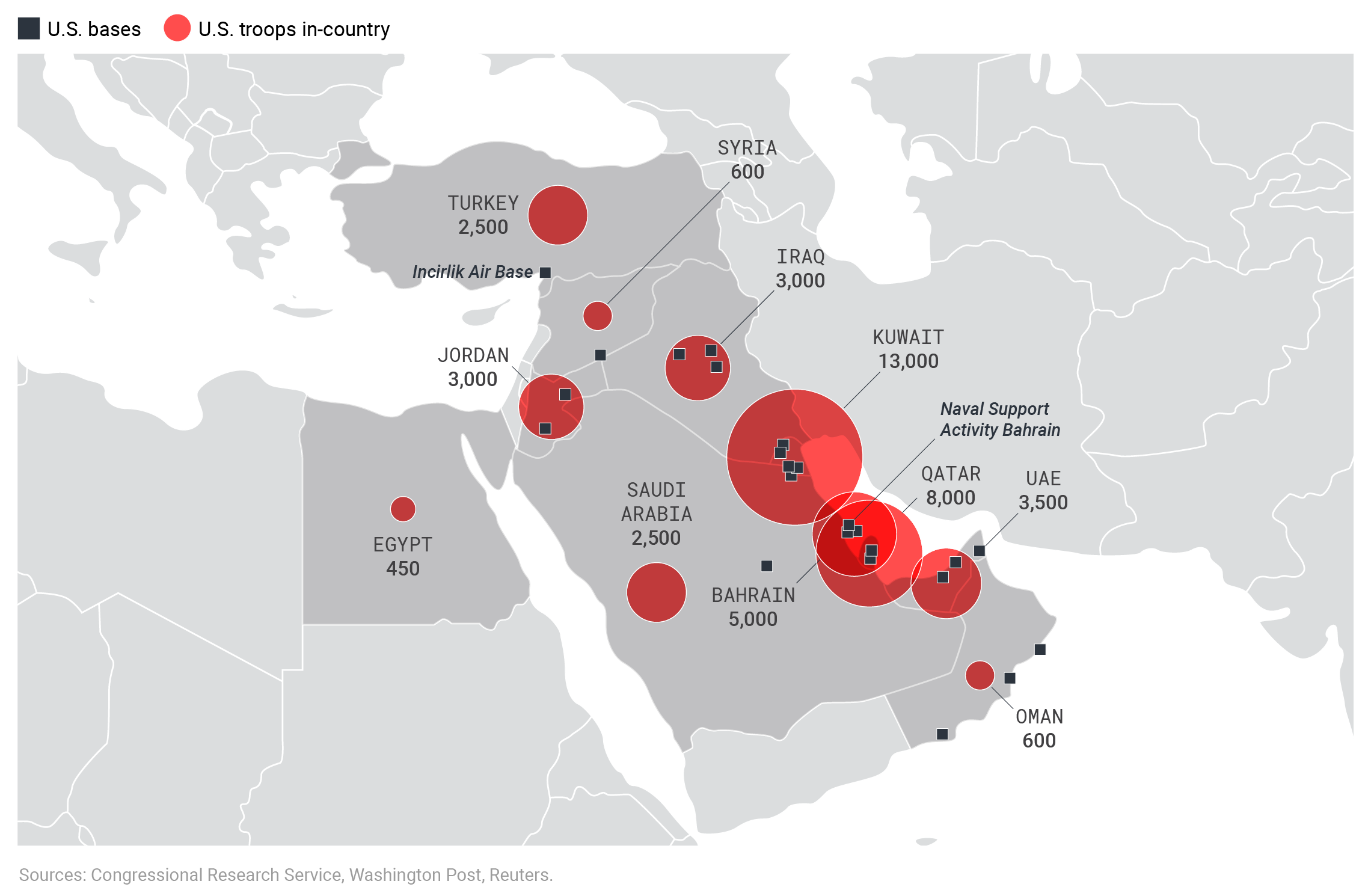

The roughly 60,000 U.S. troops in the region should leave. American efforts to manage the Middle East make nothing about oil, Israel, or terrorism better. The U.S. would be better off withdrawing all forward-deployed troops from the region, while maintaining access agreements for naval ports with the consent of host countries.

Withdrawing ground forces from the Middle East will make it harder for the U.S. to start or join any wars there. Shrinking the U.S. armed forces to reflect the lack of threat from the Middle East will free up resources for any number of higher priorities at home or abroad.

A region of limited strategic importance

The Trump administration’s National Security Strategy states that the U.S. “seeks a Middle East that is not a safe haven or breeding ground for jihadist terrorists, not dominated by any power hostile to the United States, and that contributes to a stable global energy market.”1 These priorities echo those of prior administrations. Terrorism, Israel’s well-being, and oil are the main reasons the U.S. cares about the Middle East.2

In service of these interests, the U.S. spends tens of billions of dollars every year trying to manage the region’s politics. In one of the most careful estimates of the cost savings, Eugene Gholz concludes that jettisoning the Middle East mission would produce savings on the order of $65–70 billion per year.3

The U.S. also keeps tens of thousands of military personnel on bases in the region. From Bahrain to Egypt to Iraq to Kuwait to Qatar to Syria to the United Arab Emirates, the U.S. has dozens of military bases and installations across the CENTCOM Area of Responsibility.

The U.S. has also fought wars and engaged in costly diplomacy across the region. Although some wars, like the 2011 air campaign in Libya, are not directly related to oil, Israel, or terrorism, the two wars in Iraq, the U.S. involvement in the wars in Syria and Yemen, and the “maximum pressure” campaign against Iran all grew in part from those underlying worries. Similarly, bipartisan devotion to the Saudi royal family and the Israeli government are tied to beliefs about the region’s importance to Americans.

These costly policies are puzzling because, on paper, the region is a strategic backwater. Its GDP constitutes 3.3 percent of world GDP, compared to 32.5 percent in the Western Hemisphere and 25 percent each in Europe and East Asia.4 The Middle East’s population is between 3.5 and 5 percent of the world total, depending on how one counts.5 Even if one country were to dominate—or conquer—a region with those economic and human resources, it could not pose a serious military threat to the U.S. In order to think that the region has great importance to U.S. national security, policymakers have relied on murky theories about energy economics, the regional balance of power, and the threat of terrorism.

None of these theories justify current U.S. policy in the region. U.S. interests in the Middle East do not require stationing American troops in the region. Moreover, the ideas justifying a permanent troop presence there have been wrong for decades; they did not become wrong once the U.S. became a net exporter of petroleum, or once Israel developed Iron Dome, or once Al-Qaeda was dispersed in 2001 and 2002.

U.S. military presence in the Middle East

The U.S. military maintains an outsized basing presence for ground troops in the Middle East despite the region’s marginal and shrinking strategic importance. The narrow and manageable potential threats from there can be defended against with an offshore posture.

The goal of this paper is not to lay out a detailed plan or timeframe for withdrawing U.S. troops from the region, but rather to scrutinize the justifications for U.S. policy in the region to date. Although mostly unspoken, these justifications are bad in their best rendering. If there is no good justification for a costly and destructive government policy, it should end.

Energy markets are resilient and the oil weapon is a dud

For decades, U.S. policy in the Middle East has been based on shaky premises, mostly centering on oil. These fears come in two variants. The first is that U.S. troops prevent regional wars or other types of instability that threaten the ability of oil producers to get their product onto world energy markets. So U.S. troops are thought to prevent price volatility, which could potentially hamper U.S. economic growth and war-fighting capability, as well as produce second- and third-order effects that could send the global economy into a tailspin. The second belief is that U.S. troops prevent one country from controlling so much oil production capacity that it could use its control of oil markets to extort the U.S. and other consumers.

The idea that U.S. troops are in the region to prevent instability and regional wars comes both from American clients in the region as well as U.S. officials. American politicians rarely state that U.S. troops are in the region to help control oil prices, but as former Pentagon official Ken Pollack testified in 2015, many believe “the problems of the region are creating chronic internal instability which is ultimately the greatest threat to the oil exports of the region.”6 By stationing U.S. troops in the region, this thinking goes, America can deter any aspiring regional aggressor—like Iraq in 1990 or Iran today—while assuaging the many fears of U.S. partners in the region.

One can find the second type of oil fear as far back as 1946, when the Joint Chiefs of Staff offered the political judgment that “If the peoples of the Middle East turn to Russia, this would have the same impact in many respects as the military conquest of this area by the Soviets.” They also offered a warning about economics and military power: “A great part of our military strength, as well as our standard of living, is based on oil.”7 President Truman remarked during a discussion about the Korean War that “if we just stand by, [the Soviets] will move into Iran and they’ll take over the whole Middle East.”8 Similarly, a memo from the Departments of State, Defense, Interior, and Justice to the NSC alleged that if U.S. and UK “companies were for any reason expelled from Venezuela and the Middle East, the oil from those areas would to a serious extent be lost to the free world.”9

Similar logic was at work in 1980, when President Jimmy Carter proclaimed his doctrine:

An attempt by any outside force to gain control of the Persian Gulf region will be regarded as an assault on the vital interests of the United States of America, and such an assault will be repelled by any means necessary, including military force.

At the time, the U.S. was worried about the Soviet Union seizing the Khuzestan oil fields in Iran, which would have given it control over a substantial natural resource and increased its influence over oil prices.10 Earlier, in the 1970s, the Arab oil embargo had led the Nixon administration to impose price controls, which caused severe shortages and gas lines that voters and the government attributed to the embargo, instead of the price controls.11 Confusion about energy markets and the “control of oil” led policymakers to fret about the Middle East.

The popular confusion about what caused this disruption is characteristic of how policymakers and the public think about energy security. Energy markets do not work in the way that U.S. foreign policymakers seem to believe that they do. As a leading oil economist explained in 2004, “U.S. oil policies are based on fantasies not facts.”12

How energy markets work

Oil is a fungible commodity sold on world markets. A metaphor used in the literature on oil markets is that of a bathtub into which producers pour oil and out of which consumers suck by opening a drain. What matters is how much is pouring in, how many drains are in the bathtub, and how wide open they are. Many foreign policy writers misapprehend the international oil market, assuming there is some sort of relationship between fillers and drainers—“How much Saudi oil comes to the U.S.?”—that determines a country’s energy security.

It is wrong to think of the U.S., or any country, as “dependent on Persian Gulf oil.” For that reason, efforts to foist the self-appointed U.S. role in stabilizing Middle East oil supply onto Europeans or Asians cast the problem wrongly.13 The question is not who is importing oil from the Middle East. Rather it is which countries are net importers versus net exporters and how price volatility would affect their economies.

If the states in the Persian Gulf pour more or less oil into the bathtub, that influences world price. For this reason, two energy scholars suggested in 2013 that “what Americans import from the Persian Gulf is not so much the actual black liquid as its price.”14 The same is true for all oil consumers.

When the price of oil in one country rises, it rises in all countries—even those that claim to have achieved the Shangri-La of “energy independence.” There is no way to make a country independent from the world price of oil. When supply decreases, price goes up, and producers have an incentive to produce more oil to reap the higher profits. Around the world, oil wells come on and offline, and companies increase and decrease production in response to these price signals. OPEC was created in an effort to pool member-states’ production to control what, from a producer’s point of view, are perverse incentives. The cartel seeks to maintain high, stable prices. But it fails to extinguish members’ individual interest in increasing production when price rises. Throughout OPEC’s existence, prices have been high and prices have been stable, but they have not been both for long. 15 Some scholars have argued that developments in energy markets—the shale oil revolution, for example—have diminished the Middle East’s role in oil markets. The data do not bear this out. The Middle East share of global production of petroleum and other liquid fuels has remained remarkably stable over the years, hovering close to 30 percent.

The static nature of Middle East energy production over the last three decades indicates that increased U.S. production has not made the region irrelevant to oil price concerns. The Middle East should have roughly the same effect on world petroleum prices today, at roughly 30 percent of world production, as it did in 1995, at roughly 30 percent of world production. The world simply produces and consumes more oil today than it did then. The importance of Middle Eastern oil remains roughly the same.

There is little reason to believe that political volatility in the Middle East has economic effects that warrant the costs of trying to prevent it, even if the U.S. military were able to do so. In his examination of price shocks through history, Eugene Gholz demonstrates that in all of the major oil supply shocks since 1978, prices rebounded quickly in five of the six cases due to price incentives for non-affected suppliers to ramp up production. 16

World oil production after major disruptions

The global nature of the oil market means that a major disruption in one location, temporarily reducing global supply and raising prices, incentivizes producers elsewhere to increase oil production.

Historically, most major oil price fluctuations have been the result of changing demand, not military or political tensions.17 Given that this was true both before and after the modern era (with tens of thousands of U.S. troops in the Middle East), it suggests that the presence of U.S. troops in the region is not preventing major oil price volatility today. Moreover, U.S. policy in the region has itself contributed to oil price shocks. The regime change war in Libya, tensions with Iran in 2012, and other recent U.S. policy initiatives have increased the price and volatility of oil.18

When one combines the self-interest of producers with financial innovations like sophisticated spot and futures markets that allow consumers to hedge risks, it is easy to see why even the worst supply disruptions have had limited and ephemeral effects on price.19 Nor are oil price shocks necessarily an economic calamity. Price shocks today, according to recent research, would be substantially less economically damaging than those of the 1970s, due to the declining economic burden of energy costs in countries like the U.S.20 And if one did occur, existing public and private reserves could help mitigate its effects. U.S. troops in the Middle East are not lowering the price of oil, certainly not by enough to warrant their expense.

Middle East production of petroleum and other liquids as percent of world total

The Middle East’s share of global petroleum output has remained relatively steady for decades.

The control of oil

The other big oil-related fear said to justify U.S. troop presence—preventing an oil hegemon—also does not stand up to inspection. As seen above, part of this worry relies on misunderstandings of how energy markets work, but it also overlooks the lack of plausible candidates for a run at regional hegemony. The prospect of a regional hegemon in the Middle East would warrant American policymakers’ attention and possibly a military effort, but so would an alien invasion.

For example, one possible scenario in which the U.S. military might come in handy is if a state like Iran were poised to conquer and consolidate control over a major oil terminal such as Ras Tanura in Saudi Arabia, giving it an uncomfortable, not to say market-making, amount of control over world oil markets. Fortunately, though, Iran will not have anywhere near that kind of power-projection capability in the policy-relevant future. If it did, America’s carrier-based airpower and long-range bombers could handle the threat relatively easily, meaning that nearby ground forces would not be needed. As one study of the military balance in the Gulf put it, “Iran’s land forces are shaped largely for defense in depth and seem to have limited long-range maneuver capability and uncertain survivability in the face of Arab Gulf and allied airpower.”21 This is not an offensive military power poised for conquest.

No Middle Eastern country has a shot at regional hegemony. The regional balance of power, in particular the defensive capabilities of the major states, prevents it. Power in the region is divided among Iran, Saudi Arabia (and its Gulf allies), Egypt, Turkey, and Israel. Successful conquest of even a smaller weaker state like Yemen or Lebanon would likely inflame local identity politics, which would inhibit further expansion.

Similarly, for China or Russia to dominate the Middle East, it would need to displace the governments of (at least) Iran and Saudi Arabia, then put down rebellions, establish a new, reasonably stable political order, and then usurp the vanquished states’ oil supply for its own gain, impoverishing the locals. Any such effort would likely be destructive to those aggressor countries, not beneficial. Both Russia and China have been opportunistic in the region but trying to run a remote Middle East empire from Moscow or Beijing seems unlikely to appeal to two countries that appear to have their hands full today.

In fact, after the last decades of American military experience in the region, the fear that China or Russia might displace U.S. leadership there recalls the fable of Br’er Rabbit and the briar patch. After being caught by the fox, Br’er Rabbit, understanding his plight, asks the fox to do anything with him but throw him into the briar patch below. The fox, acting purely out of spite, tosses Br’er Rabbit into the briar patch only to watch him escape from beneath the cover of the thorns, which he can navigate but the fox cannot. American policymakers might follow the example of the rabbit and trick U.S. competitors into weakening themselves by squandering money, attention, and military power attempting to run the Middle East.

The U.S. finds itself in a worse position today than in 1948, when during negotiations for the Saudi oil concession, finance minister Abdullah Suleiman “insisted that [J. Paul] Getty pay for a Saudi Army unit to defend the area of the concession against any potential Iranian or Soviet threats.”22 Dean Acheson intervened to clarify that it was illegal for private American companies to fund foreign militaries, but at least in that case the Saudis would have been defending their own oil on a private company’s dime. Today, the U.S. military holds itself responsible for protecting Middle Eastern oil, and on the American taxpayer’s dime.23

U.S. troops in the Middle East do not stabilize the price of oil. They do not protect the flow of oil to American consumers. No state inside or outside the region is poised to consolidate control over the region’s oil. Nothing about oil justifies an American military presence in the Middle East.

Israel does not need U.S. troops in the Middle East

One also hears concerns regarding the safety and power position of American partners in the region, especially Israel. For example, President Trump recently claimed, “we don’t have to be in the Middle East, other than we want to protect Israel.”24 Concern over Israel’s well-being is a longstanding component of U.S. policy. In 1970, Secretary of State William P. Rogers told Face the Nation in the context of arms sales to Israel that:

[I]t’s in our best interest to be sure that Israel survives as a nation. That’s been our policy, and that will continue to be our policy. So we have to take whatever action we think is necessary to give them the assurance that they need that their independence and sovereignty is going to continue.25

But here again, the mechanism through which Israel’s security turns on a robust American military posture in the region is unclear. Since the Israel Defense Forces shellacked the Egyptians, Syrians, and Jordanians in the Six-Day War in 1967, Israel has aggressively pursued its interests throughout the region with relative impunity, except for terrorism. (A forward U.S. military presence in the region does nothing to help the Jewish state with its terrorism problem.)

Israel today enjoys an enormous qualitative military edge over any combination of potential regional rivals in conventional military terms. Last year Israel spent $20.5 billion on its military, making it the fifteenth largest spender in the world and second largest in the Middle East behind Saudi Arabia. In the last decade Israel has increased its annual military spending by 30 percent.26 Israel also has at least 90 nuclear weapons deployed on an array of platforms, including submarines, that give it a secure second-strike capability against any state in the region that might threaten its survival.27 No other state in the region has nuclear weapons. Moreover, the maelstrom of sectarian conflict that recent U.S. policy in the region helped unleash harms, rather than benefits, Israel.

Israel likes having U.S. diplomatic cover for its policies in the Occupied Territories, but whatever the merits of providing it, doing so does not require tens of thousands of U.S. servicemembers deployed in the region. Similarly, the current Israeli leadership seems to want the U.S. to confront, or perhaps attack, Iran.28 But the conventional military balance in the region, combined with the uselessness of nuclear weapons for compellence—as opposed to deterrence—means that Israel's security does not require attacking Iran.29 American leaders should find the wherewithal to say so.

Military expenditures of Israel and Iran

Israel has substantially increased its defense spending in recent years, giving the country a decisive conventional military edge over Iran, its main rival in the region. Israel also has nuclear weapons and a secure second-strike capability to deter threats.

Iran’s lack of offensive military power combined with the growing ties between Israel and the Gulf Arabs, including Saudi Arabia, show that Iran has no hope of major conventional military gains against any of the region’s major powers. The U.S. military presence in the Middle East does nothing to protect Israel, and it does not need much protection.

Sensibly advancing nuclear nonproliferation

A concern related both to the fear of a regional hegemon and to Israel’s well-being concerns the longstanding U.S. goal of slowing or preventing the spread of nuclear weapons. U.S. policymakers have generally opposed the spread of nuclear weapons to both its partners and its adversaries since the dawn of the nuclear age. Washington opposes nuclear acquisition in its partners because it would diminish U.S. influence with those countries and grant them more say in decisions about their own defense. Washington opposes nuclear acquisition in its adversaries because, as Kenneth Waltz wrote, “if weak countries have some, they will cramp our style. Militarily punishing small countries for behavior we dislike would become much more perilous.”30

The U.S. presence in the Middle East likely makes its partners feel somewhat more secure and its adversaries somewhat less secure. If we were able to quantify the two effects, we could judge their value against one another, but they are impossible to quantify.

Even given the U.S. presence in the region, American partners in the Middle East seem to have an unslakable thirst for protection and reassurance. In the words of one former Pentagon official, they “are always trying to get us to pour more concrete.”31 Israel and the Gulf Arab states persistently request U.S. security assistance and claim their insecurity requires it. The U.S. provides almost $4 billion in military aid to Israel each year32 and the Gulf Arabs purchase tens of billions of dollars of military hardware each year.33

At the same time, Iran sees itself surrounded by hostile states, all of whom are backed to one degree or another by the U.S. American political leaders have consistently threatened Iran with preventive attack, made fanciful demands of it, and attacked Iraq and Libya while leaving North Korea alone. The obvious lesson has not been lost on Tehran.34 Even so, Iran signed the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action in 2015, which made the prospect of a nuclear Iran during the period covered by the agreement close to zero. Some analysts, including this author, questioned whether Iran would feel it could trust American commitments under the agreement, but it did so, complying with its own commitments under the deal—until the Trump administration reneged, of course.35

If the U.S. withdrew its troops from the Middle East, Saudi Arabia in particular may amplify its hints at interest in a nuclear deterrent.36 It is possible that Iran could then race for the bomb as well, though the shift in U.S. policy would undermine its incentives to do so. But the logics of nuclear acquisition apply to these states just as to any other state. Neither country has meaningful offensive military capability and nuclear weapons do not let states simply get their way in international politics. This limits their appeal, particularly given the significant economic and political costs of going nuclear.

Historically, the spread of nuclear weapons has been slow and halting, for reasons that have little to do with American regional domination.37 Americans should oppose the spread of nuclear weapons, but keeping in mind the consequences and with an eye on what is most effective. The present policy makes adversaries more likely to seek them.

Effective counterterrorism does not require permanent ground troops

Finally, there is terrorism. Here the striking fact is that less than two decades after the 9/11 attacks, the Washington establishment has almost completely moved on from the subject, yet it retains a central place in U.S. foreign policy.38 One never hears reference to a Global War on Terrorism. There are no longer any discussions of whether terrorism represents an “existential” threat.

Moreover, since the basic contours of American policy in the region predate 9/11 by decades, it is strange to think that a concern that emerged after a policy began explains the policy. But there is no evidence that terrorism is a threat that warrants an effort to manage the Middle East militarily.39 The chance of an American being killed by terrorism outside a war zone from 1970 to 2012 was roughly one in 4,000,000.40 By any conventional risk analysis, this is an extraordinarily low risk. As early as 2002, smart analysts were asking questions about counterterrorism policy such as “How much should we be willing to pay for a small reduction in probabilities that are already extremely low?”41

To the extent American policy and politics still turn on fears about terrorism, Al-Qaeda’s twitching carcass has been displaced by fears of ISIS. Its brutality and initial run of success made it sensational, but the ease with which its vaunted caliphate was dispatched indicates that it is no colossus requiring thousands of American troops to fight. Its scattered remnants, already being chased by local actors, require far less.42

Formerly ISIS-held territory in Syria and Iraq

The U.S.-led coalition destroyed the last of ISIS’s territorial caliphate in March 2019. Today, local forces are capable of hunting the scattered remnants of ISIS without the presence of the U.S. military.

Terrorist groups with serious political ambitions discover that hit-and-run insurgencies are less satisfying than seizing power and governing. Then they discover that behaving like a state makes you supremely vulnerable to American—and regional—firepower.43

The amount Americans pay now to fight Islamist terrorism—conservatively, somewhere between $50–100 billion per year, depending on how one counts—is absurdly divorced from the risk it chases.44 If someone ran a hedge fund assessing risk the way the U.S. government has responded to terrorism, it would not be long for the world. Moreover, it is difficult to identify how U.S. policy across the region—with the possible exception of some drone strikes and special operations raids—has reduced the extremely low probability of another major terrorist attack in the U.S. If anything, our policies may have increased them.45

Acknowledging reality and withdrawing from the Middle East

The idea that the Middle East is not very important for U.S. national security has begun to gain traction in the Washington foreign policy elite.46 This follows the efforts of earlier scholars during the 2000s and 2010s, all of whom made similar arguments.47 The debate appears to be broadening.

At the same time, it is unfortunate that many of the more recent analysts who argue for the limited importance of the Middle East leave rhetorical flourishes that would keep the U.S. deeply engaged in trying to run the region. For example, Mara Karlin and Tamara Cofman Wittes declared that the Middle East “matters markedly less than it used to,” and that accordingly “Washington should reduce its role in the Middle East.”48 At the same time, they suggested that America pursue the below policy objectives:

- Intervening militarily in the region's civil wars “to contain them”;

- Returning to the status quo strategy in the event “one of its core partners or interests is threatened”;

- “[P]revent[ing] new [terrorist] threats from emerging in the Middle East”; and

- Keeping “its main partners—however imperfect they are—stable and secure.”

Leaving these goals in the hands of U.S. defense policymakers—and their interpretation to America’s partners and clients in the region—is a recipe for maintaining or even expanding the U.S. role in the Middle East.

Unsurprisingly, the head of the hawkish Washington Institute for Near East Policy responded to the essay by writing that “Flesh out what it would take to achieve those objectives—the attention from the U.S. administration, the military deployments, the diplomatic effort—and one is left with a rather substantial agenda.”49

Almost all of what the U.S. needs from the Middle East, regional countries need more than the U.S. does. Without selling their oil, countries in the region would suffer terribly. Allowing one country to grow big enough to dominate the region would invite war and even state death. Given that states prefer survival and relatively favorable balances of power, we should expect states to make efforts to protect themselves. Acquiring a nuclear weapon may tantalize Iran or Saudi Arabia, but there are large costs to doing so and limited payoffs—this would be especially true in Iran’s case if Washington stopped threatening to attack the country. And although most terrorist organizations affect countries in the region far more than the U.S., Washington can credibly threaten severe punishment against any state aiding anti-U.S. terrorists.

The U.S. would profit from withdrawing almost all of its military forces from the Middle East. Leaving them there—and believing the fog-machine logics used to justify their deployment—threatens to expand the costs and prolong the suffering the region has brought to Americans, and to so many in the region. U.S. interests in the Middle East are limited, and forward-deployed military power is not needed to protect them.

Some scholars object that countries in the region help pay for U.S. bases, whereas withdrawing and then basing them at home would cost more money. But the acknowledgment that their mission does not require their efforts would mean allowing the force to shrink. That is, they would not be based in newly constructed bases in the U.S.; the U.S. would simply have a smaller military.

Hearing American foreign policy thinkers discuss the Middle East brings to mind a passage from George Orwell’s The Road to Wigan Pier, in which Orwell laments that:

[T]he high standard of life we enjoy in England depends upon our keeping a tight hold on the Empire, particularly the tropical portions of it such as India and Africa... an evil state of affairs, but you acquiesce in it every time you step into a taxi or eat a plate of strawberries and cream. The alternative is to throw the Empire overboard and reduce England to a cold and unimportant little island where we should all have to work very hard and live mainly on herrings and potatoes.50

Later, of course, England saw the Empire pried from its grip, but became a country that still had affordable taxis and strawberries and cream. Likewise, not only could the U.S. retain its way of life and prosperity having departed the Middle East, it would benefit by shedding the unnecessary costs of attempting to manage the unruly region.

If the past 20 years should have proved anything, it is that the U.S. does not have the answers to the problems of the Middle East. The good news is that it does not need them.

Costly foreign policies based on unsound logic should be updated or discarded. The justifications for U.S. policy in the Middle East are like a faded, sacred manuscript that scholars have tiptoed around for decades. It is time for policymakers to take a closer look at that manuscript and interrogate what, exactly, it says.

Endnotes

1 “National Security Strategy of the United States of America,” The White House, December 2017, 48, https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/NSS-Final-12-18-2017-0905.pdf.

2 Daniel Byman, “Assessing Current U.S. Policies and Goals in the Persian Gulf,” in Charles L. Glaser and Rosemary A. Kelanic, eds., Crude Strategy: Rethinking the U.S. Military Commitment to Defend Persian Gulf Oil (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 2016), 50.

3 Eugene Gholz, “U.S. Spending on Its Military Commitments to the Persian Gulf,” in Glaser and Kelanic, Crude Strategy, 167–195. Gholz emphasizes the importance of whether divesting from the Persian Gulf shifted defense planners from a two-war military strategy to a one-and-a-half or even a one-war strategy. If planners stuck with a two-war construct, the savings would be low: on the order of $5 billion per year in addition to any wars not fought. However, if the realization that U.S. interests in the Middle East did not necessitate a U.S. military presence in the region or the occasional war there shifted U.S. defense strategy, the savings would be significant. Another analysis from 2010 suggested the cost of the Middle East oil mission was roughly $50 billion per year, suggesting Gholz’s estimate is conservative. Michael O’Hanlon, “How Much Does the United States Spend Protecting Persian Gulf Oil?” in Carlos Pascual and Jonathan Elkind, eds., Energy Security: Economics, Politics, Strategies, and Implications (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 2010), 59–72.

4 "GDP, Current Prices," International Monetary Fund, April 2019), https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/NGDPD@WEO/OEMDC/ADVEC/WEOWORLD.

5 “World Population Prospects 2017,” United Nations Population Division, 20, https://population.un.org/wpp/Publications/.

6 "Testimony of Kenneth M. Pollack, U.S. Policy Toward a Turbulent Middle East,” U.S. Senate Armed Services Committee, March 24, 2015, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Pollack_SASC-Testimony032415-1.pdf.

7 Joint Chiefs of Staff to State-War-Navy Coordinating Committee, June 21, 1946, FRUS 1946 vol. VII, 632–633.

8 Daniel Yergin, The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money, and Power (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1991), 475.

9 Foreign Relations of the United States, 1952–1954, General: Economic and Political Matters, Vol 1, Part 2, “Report to the National Security Council by the Departments of State, Defense, the Interior, and Justice: National Security Problems Concerning Free World Petroleum Demands and Potential Supplies,” NSC 138/1, January 6, 1953, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1952-54v09p1/d279.

10 Micah Zenko, “U.S. Policy in the Middle East: An Appraisal,” Chatham House Research Paper, October 2018, 5, https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/publications/research/2018-10-18-us-military-policy-middle-east-zenko-final.pdf.

11 Jerry Taylor and Peter Van Doren, “The Case Against the Strategic Petroleum Reserve,” Cato Institute Policy Analysis no. 555, November 21, 2005, 4–5, https://www.cato.org/publications/policy-analysis/case-against-strategic-petroleum-reserve.

12 M. A. Adelman, “The Real Oil Problem,” Regulation (Spring 2004): 21.

13 Paul R. Pillar, Andrew Bacevich, Annelle Sheline, and Trita Parsi, “A New U.S. Paradigm for the Middle East: Ending America’s Misguided Policy of Domination,” Quincy Institute Paper 2, July 2020, 15–16, https://quincyinst.org/2020/07/17/ending-americas-misguided-policy-of-middle-east-domination/; Ilan Goldenberg and Kaleigh Thomas, “Demilitarizing U.S. Policy in the Middle East,” CNAS Commentary, July 20, 2020, https://www.cnas.org/publications/commentary/demilitarizing-u-s-policy-in-the-middle-east.

14 Gal Luft and Anne Korin, “The Myth of U.S. Energy Dependence,” Foreign Affairs, October 15, 2013, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/middle-east/2013-10-15/myth-us-energy-dependence.

15 M. A. Adelman, “The Clumsy Cartel,” Energy Journal 1, no. 1 (January 1980): 43–53.

16 Eugene Gholz, “Restraint and Oil Security,” in A. Trevor Thrall and Benjamin H. Friedman, eds., U.S. Grand Strategy in the 21st Century: The Case for Restraint (New York: Routledge, 2018), 58–79.

17 Lutz Kilian, “Oil Price Shocks: Causes and Consequences,” Annual Review of Resource Economics 6 (2014): 133–154.

18 Christiane Baumeister and Lutz Kilian, “Forty Years of Oil Price Fluctuations: Why the Price of Oil May Still Surprise Us,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 30, no. 1 (Winter 2016): 147.

19 Philip E. Auerswald, “Energy Conundrums: The Myth of Energy Insecurity,” Issues in Science and Technology 22, no. 4 (Summer 2006); Gholz and Press.

20 Olivier J. Blanchard and Jordi Galí, “The Macroeconomic Effects of Oil Price Shocks: Why Are the 2000s So Different from the 1970s?” in Jordi Galí and Mark J. Gertler, eds., International Dimensions of Monetary Policy (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009), 373–421.

21 Anthony H. Cordesman and Nicholas Harrington, “The Arab Gulf States and Iran: Military Spending, Modernization, and the Shifting Military Balance,” Center for Strategic and International Studies Working Paper, December 12, 2018, 17, https://www.csis.org/analysis/arab-gulf-states-and-iran-military-spending-modernization-and-shifting-military-balance. I do not deal in detail with the prospect of Saudi Arabia conquering Iran because Saudi Arabia has even less offensive military capability than Iran.

22 Yergin, Prize, 442.

23 On October 16, 2019, President Trump falsely claimed that “Saudi Arabia has graciously agreed to pay for the full cost of everything we’re doing for them… And that negotiation took a very short time—like, maybe, about 35 seconds.” The White House, State Department, and Defense Department all declined to explain how Riyadh would be paying. Glenn Kessler, “Trump’s Claim That the Saudis Will Pay ‘100 Percent of the Cost,’“ Washington Post, October 21, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2019/10/21/trumps-claim-saudis-will-pay-percent-cost/.

24 Barbara Boland, “White House Touts Plan to Decrease Iraq Troop Levels to 3K Soon,” American Conservative, September 10, 2020, https://www.theamericanconservative.com/articles/white-house-touts-plan-to-decrease-iraq-troop-levels-to-3k-soon/.

25 “Interview with Secretary of State William P. Rogers,” Face the Nation, June 7, 1970. Transcript included in the Department of State Bulletin LXII, no. 1618, 785–792, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=msu.31293008121992&view=1up&seq=1.

26 Nan Tian, Alexandra Kuimova, Diego Lopes da Silva, Pieter D. Wezeman, and Siemon T. Wezeman, “Trends in World Military Expenditure, 2019,” Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, April 2020, https://www.sipri.org/publications/2020/sipri-fact-sheets/trends-world-military-expenditure-2019.

27 Israel reportedly has enough plutonium for at least another 100 weapons. See Center for Arms Control and Nonproliferation, “Fact Sheet: Israel’s Nuclear Arsenal,” March 31, 2020, https://armscontrolcenter.org/fact-sheet-israels-nuclear-arsenal/.

28 Josh Lederman, “Netanyahu Appears to Say War with Iran Is Common Goal,” NBC News, February 13, 2019, https://www.nbcnews.com/news/world/netanyahu-appears-say-war-iran-common-goal-n971266; Ronen Bergman and Mark Mazzetti, “The Secret History of the Push to Strike Iran,” New York Times, September 4, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/04/magazine/iran-strike-israel-america.html.

29 Todd S. Sechser and Matthew Fuhrmann, Nuclear Weapons and Coercive Diplomacy (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2017). Indeed, the consequences of such an attack, including the blowback via Iranian linked forces near Israel’s borders, would likely damage its security.

30 Kenneth N. Waltz, “Waltz Responds to Sagan,” The Spread of Nuclear Weapons: A Debate, Kenneth N. Waltz and Scott D. Sagan, eds., (New York: W.W. Norton, 1995), 111. Or, as Thomas Donnelly wrote, “A nuclear-armed Iran is doubly threatening to U.S. interests not only because of the possibility it might employ its weapons or pass them to terrorist groups, but also because of the constraining effect it will have on U.S. policy in the region.” Donnelly, “Strategy for a Nuclear Iran,” Getting Ready for a Nuclear-Ready Iran, Henry Sokolski and Patrick Clawson, eds., (Carlisle, PA: Strategic Studies Institute, 2005), 159.

31 Daniel Benaim and Michael Wahid Hanna, “The Enduring American Presence in the Middle East,” Foreign Affairs, August 7, 2019, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/middle-east/2019-08-07/enduring-american-presence-middle-east.

32 Jeremy M. Sharp, “U.S. Foreign Aid to Israel,” Congressional Research Service RL33222, August 7, 2019, https://www.everycrsreport.com/files/20190807_RL33222_54f0e84c97f844c91d228835e6cbbd1618f97a2d.pdf.

33 Cordesman and Harrington.

34 As Kenneth Pollack admitted in 2006, “We didn’t invade North Korea because they had a nuclear weapon. We did invade Iraq because they didn’t have a nuclear weapon, but we thought they were trying to get one. If you’re Iran, what is the logical lesson?” Anne Gearan, “Analysis: Iraq War Ties U.S. Hands on Iran,” Associated Press, June 2, 2006.

35 Justin Logan, “U.S. Policy Toward Iran: Prospects for Success—and for Failure,” Cato Institute Conference, March 30, 2012, https://www.cato.org/events/us-policy-toward-iran-prospects-success-failure.

36 Saudi Arabia has dallied with nuclear technology for years, most recently in concert with China. Warren P. Strobel, Michael R. Gordon, and Felicia Schwartz, “Saudi Arabia, With China’s Help, Expands Its Nuclear Program,” Wall Street Journal, August 4, 2020, https://www.wsj.com/articles/saudi-arabia-with-chinas-help-expands-its-nuclear-program-11596575671.

37 John Mueller, Atomic Obsession: Nuclear Alarmism from Hiroshima to Al Qaeda (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 89–103.

38 Presidential candidate Joe Biden says that in the Middle East “our security interests are enduring but not unlimited. Our top priority should be counterterrorism.” Leo Shane III, “Military Times Questionnaire: Former Vice President Joe Biden,” Military Times, November 18, 2019, https://www.militarytimes.com/news/pentagon-congress/2019/11/18/military-times-questionnaire-former-vice-president-joe-biden/.

39 John Mueller and Mark G. Stewart, “Responsible Counterterrorism Policy,” Cato Institute Policy Analysis no. 755, September 10, 2014, https://www.cato.org/publications/policy-analysis/responsible-counterterrorism-policy.

40 Mueller and Stewart.

41 Howard Kunreuther, “Risk Analysis and Risk Management in an Uncertain World,” Risk Analysis 22, no. 4 (August 2002): 655–664.

42 Benjamin H. Friedman and Justin Logan, “Disentangling from Syria’s Civil War: The Case for U.S. Military Withdrawal,” Defense Priorities, May 2019, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/disentangling-from-syrias-civil-war.

43 Friedman and Logan, 9–10.

44 Mueller and Stewart.

45 In 2003, Paul Wolfowitz noted that the presence of U.S. forces in Saudi Arabia had been a “huge recruiting device” for Al-Qaeda and constituted one of Osama bin Laden’s “principal grievances.” For Wolfowitz, the Iraq War was attractive in part because it would allow Washington to withdraw these troops. “Deputy Secretary Wolfowitz with Sam Tannenhaus, Vanity Fair,” U.S. Department of Defense, May 9, 2003, https://archive.defense.gov/Transcripts/Transcript.aspx?TranscriptID=2594.

46 Martin Indyk, “The Middle East Isn’t Worth It Anymore,” Wall Street Journal, January 17, 2020, https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-middle-east-isnt-worth-it-anymore-11579277317; Mara Karlin and Tamara Coffman Wittes, “America’s Middle East Purgatory: The Case for Doing Less,” Foreign Affairs (January/February 2019), 88–100, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/middle-east/2018-12-11/americas-middle-east-purgatory; Goldenberg and Thomas; Mike Sweeney, “Considering the ‘Zero Option,’” Defense Priorities, March 2020, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/considering-the-zero-option.

47 Philip E. Auerswald, “The Myth of Energy Insecurity,” Issues in Science and Technology XXII, no. 4 (Summer 2006), https://issues.org/auerswald-2/; Auerswald, “The Irrelevance of the Middle East,” American Interest 2, no. 5 (May/June 2007), https://www.the-american-interest.com/2007/05/01/the-irrelevance-of-the-middle-east/; Edward Luttwak, “Middle of Nowhere,” Prospect (UK), May 26, 2007, http://www.prospectmagazine.co.uk/features/themiddleofnowhere; Toby C. Jones, “Don’t Stop at Iraq: Why the U.S. Should Withdraw From the Entire Persian Gulf,” Atlantic, December 22, 2011, https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2011/12/dont-stop-at-iraq-why-the-us-should-withdraw-from-the-entire-persian-gulf/250389/; Justin Logan, “Why the Middle East Still Doesn’t Matter,” Politico Magazine, October 9, 2014, https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2014/10/why-the-middle-east-still-doesnt-matter-111747; Glaser and Kelanic; Emma Ashford, “Unbalanced: Rethinking America’s Commitment to the Middle East,” Strategic Studies Quarterly (Spring 2018): 127–148, https://www.cato.org/sites/cato.org/files/articles/ashford-ssq-november-2018.pdf.

48 Karlin and Wittes.

49 Robert Satloff, “Commitment Issues,” Foreign Affairs (May/June 2019), https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/middle-east/2019-04-16/commitment-issues.

50 George Orwell, The Road to Wigan Pier (New York: Harcourt Brace & Co, 1958 [1937]), 159–160.