Narrow targeted killings to terrorists with the capability and intent to attack the U.S.

- Targeted killings are the deliberate use of lethal force against a specific combatant who is not already in custody. They are an oft-used tool of U.S. counterterrorism policy, generally executed by armed unmanned aerial vehicles (drones), manned aircraft, or cruise missile strikes.

- This paper is chiefly concerned with the overuse of targeted killings, especially by drones, not the existence or use of any particular technology.

- The U.S. developed drones for surveillance during the Cold War. Equipped with HD cameras, GPS navigation, and laser-guided hellfire missiles, drones became independently capable of targeted killing—just about when Al-Qaeda’s attacks ramped up demand for this capability in 2001.1

- The U.S. continued drone strikes—in at least seven countries since 2018—even as it reduced combat operations in the greater Middle East in recent years. In December 2021, the U.S. killed a senior Al-Qaeda planner in Syria using a MQ-9 Reaper drone.2

U.S. drone and air strikes between 2018 and 2020

The U.S. conducted drone and air strikes in at least seven countries since 2018 as part of the Global War on Terror, expanding the list to at least 79 countries in which the U.S. military conducted strikes or provided training and assistance.

- Three general objectives of targeted killings are:

1) Disruption, where strikes keep terrorists on the run to degrade their organizations’ ability to function and erode their morale;

2) Decapitation, which means killing a group’s leaders to achieve those results; and

3) Elimination, where strikes aim to kill off an organization entirely.3

- The U.S. does face threats, and the correct number of U.S. targeted killings abroad is unlikely to ever reach zero. Yet U.S. strikes should be focused on exceptional circumstances, where taking life stops terrorists with the capability and intent to attack the U.S.

What are the incentives to use targeted killings?

- U.S. military casualties and deaths are politically costly. Compared to using other kinds of military force, targeted killings are a low-cost, low-risk tool to eliminate terrorist leaders, inflict damage on terrorist groups, and disrupt the planning of future terror attacks.

- Targeted killings via drones and missiles are often used in areas where local governance is weak and deploying U.S. troops is dangerous. The military can launch such attacks from afar at little immediate risk to U.S. troops.

- Killing terrorist leaders and facilitators can be tactically effective: forcing terrorist groups to elevate less experienced replacements, prioritize survival over external attack planning, and limit communications. It can also generate suspicion about informants among the rank-and-file.4

- Targeted killings via drones and air strikes have killed high-profile terrorists, including ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi in Syria, Al-Qaeda deputy commander Abu al-Khayr al-Masri in Syria, and AQAP chief Qasim al-Raymi in Yemen.

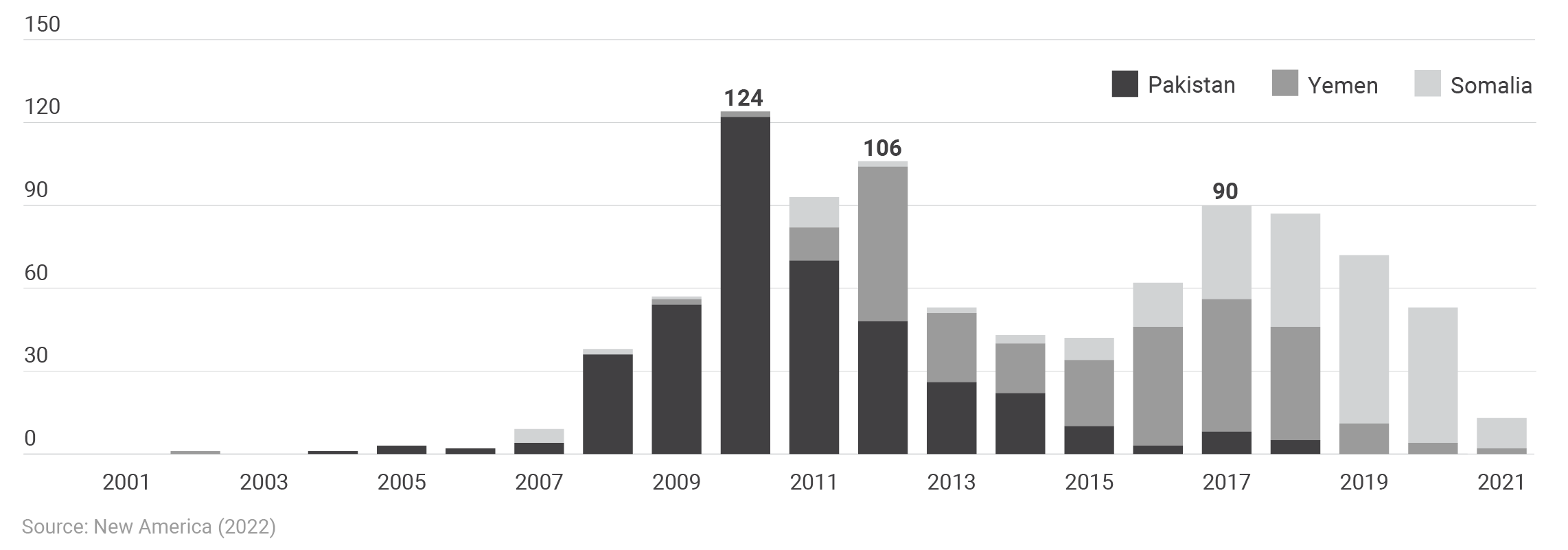

U.S. air and drone strikes in Pakistan, Yemen, and Somalia

Complete accounting of U.S. targeted killings is not public, but recorded U.S. air and drone strikes in Pakistan, Yemen, and Somalia illuminate the pace of targeted killings from year to year.

Why targeted killings do not work as intended

- Targeted killings prioritize short-term results over longer-term outcomes, tactics over strategic effect. The low risk to U.S. forces, the ease with which the U.S. can conduct strikes, and an assumption that decapitation strikes will neutralize terrorist organizations propel a self-reinforcing hunt for targets.

- Inaccurate intelligence and a bias toward lethal action exacerbate the risks of civilian casualties and tragic failures.5 There is no such thing as a clean war, no matter how sophisticated the technology used.

- Even with good intelligence and care taken to avoid it, it is not uncommon for drone and air strikes to kill innocent civilians, as in an errant strike in Afghanistan in August 2021, which killed ten civilians, including an aid worker.6

- Civilian causalities generate “blowback” in the form of anti-U.S. hostility that can boost terrorists’ recruitment efforts, undermine cooperation of host governments, and create other negative effects.7

- Strategic counterterror success remains elusive. Killing high-profile terrorist operatives can interrupt a group’s operations for a time, but it is unlikely to end them, resulting in open-ended campaigns.8 There are as many as three times as many Islamic terrorist groups today than there were before 9/11.9

- Narrowing the focus of U.S. counterterrorism efforts is a better strategy. The most effective forms of counterterrorism are policing and cooperation with foreign security services or even militias. Direct U.S. strikes are a useful tool of counterterrorism that should be used more rarely.

Targeted killings expanded with the war on terror

- The first known targeted killing operation after 9/11 occurred on October 7, 2001, when a series of missiles targeted the compound of Taliban leader Mohammad Omar in Kandahar, Afghanistan, but failed to kill him.10

- The Bush administration conducted a total of 61 strikes in Pakistan, Yemen, and Somalia. Forty-eight occurred in Pakistan, with 38 percent targeting Al-Qaeda fighters in the tribal areas near the Afghan-Pakistani border.11

- The Obama administration increased the pace of strikes, including so-called “signature strikes.” First authorized under the Bush administration, signature strikes authorize lethal action against unidentified militants within a strike zone based on observed patterns of behavior. Identifying individuals is not required to kill them.12

- By the end of President Obama’s second term, the U.S. launched a combined 586 strikes in Pakistan, Yemen, and Somalia—a nearly 10-fold increase from the prior administration.13

- Continuing the practice of signature strikes, President Trump also granted more operational control to military commanders and CIA operatives on the ground. The Trump administration issued rules lowering the evidence threshold for killing suspected militants.14

Terrorist leaders are a fraction of the total killed in U.S. drones strikes

The overwhelming majority of deaths from U.S. drone and air strikes are not terrorist leaders but other people, including militants, civilians, and unknown deaths.

- In Somalia, the Trump administration conducted 202 drone strikes—more than three-times the number of the previous two administrations combined. Over the same period, however, strikes in Pakistan declined and then stopped in 2018 due to the U.S. winding down the war in Afghanistan. Strikes in Yemen also declined from 41 in 2018 to just 4 in 2020.

- In its first year, the Biden administration tightened the rules of engagement, requiring White House approval for strikes in countries with few U.S. troops.15 The number of strikes in Somalia and Yemen fell in 2021 from 2020.

- In Iraq and Syria, U.S. drones and aircraft released an average of 726 munitions per month in 2018, but just 47 in 2021. In Afghanistan, the U.S. has not launched a drone strike since the last U.S. troops withdrew at the end of August 2021.16

The U.S. should narrow the scope of its targeted killing operations

- The Biden administration is currently completing a review of U.S. targeted killing policy. The review should institutionalize the recent decrease in strikes and place stricter limits on when, where, and against whom the U.S. employs them.

- The U.S. should prioritize the few transnational terrorist groups with the capability and intent to strike the U.S., not insurgents fighting for local aims (such as Al-Shabaab in Somalia, Islamist militants in Mali, or most of the remnants of ISIS in Syria and Iraq).

- The government should provide greater public transparency on how targets are established, how strike decisions are made, the number of strikes conducted per year, details on individual targets, and cases of civilian casualties.

- Congress could reclaim its power to oversee targeted killings. It could repeal the 2001 AUMF, which grants broad authority for these strikes; increase its public oversight hearings; and create an independent, civilian-led oversight board to ensure allegations of civilian casualties are adequately assessed, with all findings and conclusions released to the public.

- U.S. policymakers should not view the additional measures outlined above as a replacement for a larger assessment on whether to continue the Global War on Terrorism. Adopting measures to curtail its excesses is not a way to shirk decisions about whether to end it.

Endnotes

1 Alexander Farrow, “Drone Warfare as a Military Instrument of Counterterrorism Strategy,” Air and Space Power Journal vol. 28, no. 8 (December 2016): 4–12.

2 “Pentagon Press Secretary John F. Kirby Holds an On-Camera Press Briefing,” U.S. Department of Defense, December 6, 2021, https://www.defense.gov/News/Transcripts/Transcript/Article/2863617/pentagon-press-secretary-john-f-kirby-holds-an-on-camera-press-briefing/.

3 Bryan C. Price, “Targeting Top Terrorists: How Leadership Decapitation Contributes to Counterterrorism,” International Security vol. 36, no. 4 (April 2012): 9–46; Benjamin H. Friedman, “Countering Terrorism with Targeted Killings,” Cato Institute, accessed January 14, 2022, https://www.cato.org/cato-handbook-policymakers/cato-handbook-policy-makers-8th-edition-2017/67-countering-terrorism-targeted-killings.

4 Daniel L. Byman, “Why Drones Work: The Case for Washington’s Weapon of Choice,” Brookings Institution, June 17, 2013, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/why-drones-work-the-case-for-washingtons-weapon-of-choice/.

5 Eric Schmitt, “A Botched Drone Strike in Kabul Started with the Wrong Car,” New York Times, updated November 3, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/09/21/us/politics/drone-strike-kabul.html.

6 Charlie Savage, Eric Schmitt, Azmat Khan, Evan Hill, and Christoph Koettl, “Newly Declassified Video Shows U.S. Killing of 10 Civilians in Drone Strike,” New York Times, January 19, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/01/19/us/politics/afghanistan-drone-strike-video.html.

7 John P. Abizaid and Rosa Brooks, “Recommendations and Report of the Task Force on U.S. Drone Policy: Second Edition,” Stimson, April 2015, http://stimson.org/wp-content/files/file-attachments/recommendations_and_report_of_the_task_force_on_us_drone_policy_second_edition.pdf.

8 Jenna Jordan, Leadership Decapitation: Strategic Targeting of Terrorist Organizations (Stanford University Press: Redwood City, California, 2019): https://www.sup.org/books/extra/?id=30621&i=Excerpt%20from%20Introduction.html.

9 Seth G. Jones, “The Evolution of the Salafi-Jihadist Threat,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, November 20, 2018, https://www.csis.org/analysis/evolution-salafi-jihadist-threat.

10 Chris Woods, “The Story of America's Very First Drone Strike,” Atlantic, May 30, 2015, https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2015/05/america-first-drone-strike-afghanistan/394463/.

11 Peter Bergen, David Sterman, and Melissa Salyk-Virk, “America’s Counterterrorism Wars,” New America, accessed January 14, 2022, https://www.newamerica.org/international-security/reports/americas-counterterrorism-wars/.

12 Eric Schmitt and David E. Sanger, “Pakistan Shift Could Curtail Drone Strikes,” New York Times, February 22, 2008, https://www.nytimes.com/2008/02/22/washington/22policy.html.

13 Peter Bergen, David Sterman, and Melissa Salyk-Virk, “America’s Counterterrorism Wars.”

14 Audrey Kurth Cronin, “The Future of America’s Drone Campaign,” Foreign Affairs, October 14, 2021, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/afghanistan/2021-10-14/future-americas-drone-campaign.

15 Ellen Nakashima and Missy Ryan, “Biden Orders Temporary Limits on Drone Strikes Outside War Zones,” Washington Post, May 4, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/national-security/biden-counterterrorism-drone-strike-policy/2021/03/04/f70fedcc-7d01-11eb-85cd-9b7fa90c8873_story.html.

16 “Combined Forces Air Component Commander 2014-2021 Airpower Statistics,” U.S. Air Forces Central, December 2021, https://www.afcent.af.mil/Portals/82/December%202021%20Airpower%20Summary_FINAL.pdf.