Key points

The wisdom of making wars easier depends on the wisdom of the wars. Rapid military response to all global trouble may sound good, but it can tempt policymakers to intervene even for non-vital interests.

U.S. military bases and logistics hubs in and near the Middle East are the primary examples—they make foolish wars too easy to start.

Maintaining the ability to use rapid military force in the region has become an end unto itself, unmoored from any clear vital strategic interest.

Closing bases will make wars more challenging to start, which will help spur public debate about potential interventions due to the transparent upfront costs required. This will give diplomacy an opportunity to return as the primary policy option in the region.

This recommendation is consistent with the U.S. Constitution’s logic. Democracy’s benefit for foreign policymaking is its ability to consider many options and give more time to think through various proposals.

The logistics of a global military posture and the temptation problem in the Middle East

The Department of Defense’s (DoD) recent Global Posture Review, rather than considering any major re-orientation or new strategic thinking, cemented the existing posture, and failed to further disengage the United States from the Middle East.1 Even with President Joe Biden promising to end endless wars in the region, his administration wants current basing to remain in case of unforeseen contingencies and to serve as a theoretical stabilizing presence in the region.2 It seemingly has not considered how the presence of these bases contributes to the instability and endless wars he says he wants to end.

U.S. defense strategy sees military tools that facilitate combat in key global regions as an unvarnished good.3 As a consequence of this strategy, U.S. military posture has developed to include more than 600 bases in 45 countries, supported by a rapidly deploying intervention force with global reach.4

This force posture rests on an unstated assumption that logistical capacity and basing infrastructure to support it will not tempt policymakers into unwise and costly interventions for non-strategic interests. Current military posture obscures the true costs of each additional use of force in a region because it places intervention on permanent retainer.5 To begin a new intervention, the necessary manpower and material do not require costly and lengthy mobilization from outside the region. With marginal costs (in time and resources) lower, temptation to use military force to intervene increases, as Kenneth Waltz explains: the United States’ “ability to act militarily carries with it the temptation to take military action.”6

This dynamic is most recognizable in the Middle East, where a preponderance of power allowed the United States to grow an expansive presence for counterterrorism, and European bases became critical logistics hubs to help serve these wars. As a result, the United States turns to its military in the Middle East too quickly, taking advantage of the ease of deployment and overlooking long-term costs.7 In the words of former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, this belief manifests as: “What’s the point of having this superb military you’re always talking about, if we can’t use it?”8

Maintaining the current force posture allows policymakers to avoid re-thinking the logic of U.S. presence in the region. Limited anti-U.S. terror threats—that can be better thwarted via intelligence and targeted strikes and raids—mean securing vital U.S. interests does not require a permanent presence.9 Indeed, permanent bases harm U.S. interests there, and closing bases will help future presidents avoid strategic temptation and appreciate the actual costs of wars.

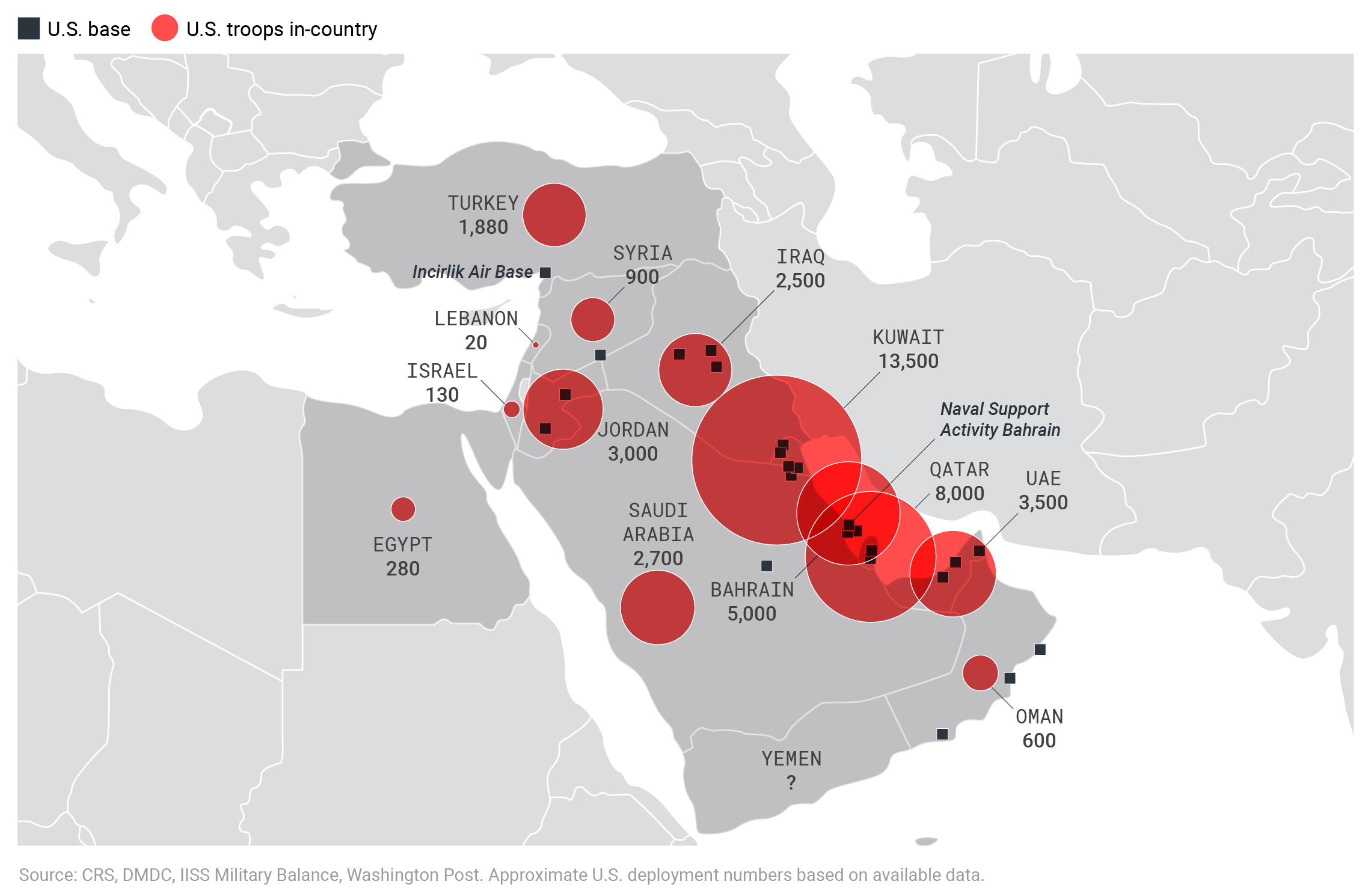

U.S. bases and troop levels in the Middle East

The U.S. military maintains an outsized basing presence for ground troops in the Middle East, which tempts policymakers to use force in a region increasingly marginal to U.S. national security interests.

Putting intervention on retainer leads to the problem of temptation

The problem of temptation means that more forward basing and easier logistics increases the risk of engaging in unwise wars. While some wars would, of course, still occur with a less expansive military posture, the problem of temptation highlights that with greater debate and upfront cost transparency, the time and effort required to mobilize for war could serve as a brake on some unwise interventions. Further, there is a path dependency created from previous wars where the basing and logistical presence created to facilitate that mission remain present after the conflict, permitting the easier use of force in the future.

The current over-militarized U.S. foreign policy in the Middle East results from the preponderant power that the United States has enjoyed since the end of the Cold War. U.S. global power projection capacity has led Washington to viewing global instability as a U.S. responsibility to solve. Fear of regional instability intensified following 9/11, and U.S. basing expanded to support the wars in Iraq, Afghanistan, and other areas in the region. These wars also required support from supply lines through Europe. Existing bases in Europe filled this role—a useful way to renew their purpose after the Cold War. However, even after the logic behind the Global War on Terror (GWOT) and the invasion of Iraq proved faulty, the infrastructure put in place to facilitate these wars remained, tempting policymakers to escalate and start new wars in the region.

Timeline of U.S. interventionS in the IRAQ

The United States’ perpetual interventions in Iraq over the last 30 years serve as a powerful example of how U.S. force postures contribute to an over-militarized foreign policy.

The temptation problem helps explain why presidents cannot seem to deliver on restraint-minded rhetoric. Each of the last four presidential administrations arrived in office after campaigning against the incumbent’s overly-interventionist foreign policy. President George W. Bush derided the nation-building of the Clinton administration, and President Barack Obama campaigned against the disastrous Iraq War.10 President Donald Trump scorned nation-building, while President Biden ridiculed previous administrations for not ending the so-called forever wars.11 Yet each president who campaigned on stopping the interventionist mistakes of the previous administration started new conflicts or escalated existing ones in the Middle East, with President Biden being the notable exception so far. The reasons for this are many and complex, but bases helped: they made it easy to start new interventions and allowed presidents to discount war costs required for each due to the yearly infrastructure retainer paid through the DoD budget. This inability to resist continuous intervention in the region due to the logistical ease of doing so is the strategic problem of temptation.

The current logistical posture

Temptation is most apparent in the Middle East, where the U.S. continues to frequently use military force throughout the region, even as policymakers promise to emphasize great power threats instead.12 To permit for this operational tempo, the United States deploys around 36,500 troops across 18 bases in Kuwait, Qatar, Bahrain, UAE, Jordan, Iraq, Oman, and Saudi Arabia.13 This includes forward basing at Camp Arafjan in Kuwait, Al-Asad Air Base in Iraq, and Al Udeid Air Base in Qatar and relying on prepositioned materiel at Kuwait’s International Airport and the aforementioned Al Udeid Air Base. U.S. combat aircraft and Patriot missile systems are stationed at Al Dhafra airbase in the UAE and Shaykh Isa Air Base in Bahrain, and the U.S. military maintains its own access to the Jebel Ali Port and Port Khalifa bin Salman, including the Naval Support Activity Bahrain complex that houses the Fifth Fleet. U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM) also relies on maritime prepositioning ships stationed in Diego Garcia for logistical needs if mobilizing for conflict.14

Perhaps more important, European bases have been largely transformed to “logistically supporting other combatant commands…including (CENTCOM) and U.S. Africa Command (AFRICOM)” following the Cold War.15 Regular operations in the Middle East and North Africa meant these bases serve as logistics hubs rather than operational forward basing focused on potential great power threats, hampering readiness. Today, for instance, the U.S. Army’s 21st Theater Sustainment Command at Rammstein and Mihail Kogalniceanu Air Base in Romania serve as significant logistics hubs for CENTCOM and house material needed for Middle East contingencies.16

U.S. military and DoD personnel deployed overseas

U.S. troops and bases in Europe have increasingly been employed as logistical support for other regions, specifically Africa and the Greater Middle East.

The overemphasis on rapid response

This current basing and logistical posture is built on the assumption that surging force rapidly to a region is a priority and necessary for U.S. strategic interests. It prioritizes the rapid use of force—seen as a net positive for U.S. intervention—but this is the problem. Examining the logic behind the emphasis on rapid response for the region and its role in subverting democratic foreign policy’s benefits helps illustrate the temptation problem this creates.

The emphasis on rapidity first emerged as a part of the Carter Doctrine that committed U.S. forces to stabilize the Middle East in case of a Soviet movement to control the Persian Gulf following the invasion of Afghanistan out of fear of what it could mean for global oil markets. It was a dubious argument then, but even more dubious now with no credible hegemonic threat and developments that insulate the United States from oil shocks.17 Following this fear of not having rapid military options to keep the Persian Gulf open, the Rapid Deployment Force, later the Rapid Deployment Joint Task Force (RDJTF), was created. A few years later, though, the RDJTF was turned into a permanent combatant command that still exists today—CENTCOM.18

Rapidity regained steam as an idea to support the GWOT, with the 2004 Global Posture Review advocating for “less emphasis on numbers of forward forces than upon capabilities and desired effects that can be achieved rapidly.” In justifying basing and deployments in Iraq and Syria today, the Biden administration’s Global Posture Review similarly calls for the United States to “always have the capability to rapidly deploy forces to the region based on the threat environment.”19 It reflects the troublesome idea that the ability to send force rapidly is more important than considering what purpose the force will serve.20

To support this preference for rapid options, defense planning emphasizes global logistical infrastructure. As a 2013 RAND report states, “U.S. defense strategy calls for a global response capability, so posture decisions should maintain an effective global en route infrastructure. The United States can maintain relatively rapid global response capabilities as long as this infrastructure and strategic lift assets are maintained.”21 As seen above, this mindset encourages the United States to maintain basing structure in Europe that would facilitate “rapidly deployable for early entry into conflict well beyond Europe,” specifically the Middle East.22

The 2011 crisis in Libya highlights how the logistics that permit rapidity can tempt policymakers into poor intervention decisions. As the crisis unfolded, it became clear that even though Libya was in AFRICOM’s area of responsibility, the rapid intervention could only be carried out from European bases with prepositioned forces and material. U.S. and NATO planners turned to Aviano and Sigonella in Italy, Moron and Rota in Spain, and Souda Bay in Greece to base air operations and manage the mission’s logistics.23 Each of these bases existed during the Cold War, but they transformed during the GWOT to support logistics and operations in Iraq, Afghanistan, and the Middle East.24

It was relatively simple to re-route this logistics flow to North Africa and prepare for Operation Odyssey Dawn and Operation Unified Protector, the U.S. and NATO-led military interventions in Libya. In less than a month from the first calls of a no-fly zone for Libya at the U.N., the United States started a new war that had profound consequences still reverberating today. Given that other NATO allies wanted to move fast in the intervention, existing U.S. forces were called upon to maintain the no-fly zone and target various government forces. Without the pre-positioned material and logistical hubs the United States maintained, the mission would have needed to be much smaller, or it would have required more preparation time. The logistics developed in Europe to support wars in the Middle East and Afghanistan provided an efficient means to prepare for a rapid intervention in Libya.25

This quick movement obviated the need for a healthy debate about whether the war truly served U.S. interests. With the material already in Europe, the U.S. intervention proceeded before the American public, or even their congressional representatives, could debate mobilization. It only took 10 days to act compared to the 11 months required to mobilize for the Kosovo War over a decade earlier.26 The retainer fee paid to facilitate this intervention appeared worth it at the time, but the pace at which the mission moved did not allow proper consideration of the cost which proved high in the long run, a regret even President Obama shares now.27

Overall, rapid response capabilities create the temptation “to strike quickly to nip trouble in the bud” without thinking if it genuinely achieves any strategic ends.28 Rapid response further engenders a feeling of having to act now, which means military policymakers focus more on whether they can do something than if they should. Making force deployments emphasize rapidity reduces cost transparency while simultaneously reducing the amount of time built in to consider if military options are the right course. This limits the time to consider the strategic rationale of the mission in depth.29

Side-stepping the benefits of democratic foreign policy

The emphasis on rapid response also subverts the virtues of democratic foreign policymaking. Policymakers desire more readily available military options because they feel that if presidents have multiple options to use force quickly, they can select between them to provide better strategic outcomes.30 In reality, it often does the opposite—tempting policymakers into unwise intervention.

Bernard Brodie highlighted this problem when he questioned “the notion that expanding the [p]resident’s military options is always a good thing.”31 Instead of considering all issues related to the deployment of force, he argued that presidents end up with an extensive menu of military options presented that tempt them because the upfront costs appear lower and the interventions easier to implement due to pre-exisiting logistics. As Brodie anticipated, the robust U.S. military posture in the Middle East undermines the supposed democratic benefits of providing decision-makers multiple options. The ease of selection means that less effort and time is put into understanding all costs required to support the mission accurately. This subverts the way the United States should make strategic choices, where deliberation and consideration should precede policy response.

The desire for rapid response also can create a form of self-entrapment, where the desire for a small force to maintain future flexibility ends up entrapping the United States in a more permanent intervention without broader democratic debate on its merits. Today, the United States faces this problem in Iraq, Syria, Iran, Yemen, and Saudi Arabia. In each, continued U.S. presence suffers from a self-fulfilling rationale for its existence. For instance, in response to Iranian strikes on Saudi Arabian oil facilities in 2019, President Trump ordered the deployment of U.S. forces, F-15s, and THAAD missile defense systems to Saudi Arabia to deter future strikes. There was limited American appetite for broader military conflict to defend Saudi oil fields. Still, given existing assets in the region, it was logistically simple to deploy back to the bases that were left 17 years previously.32

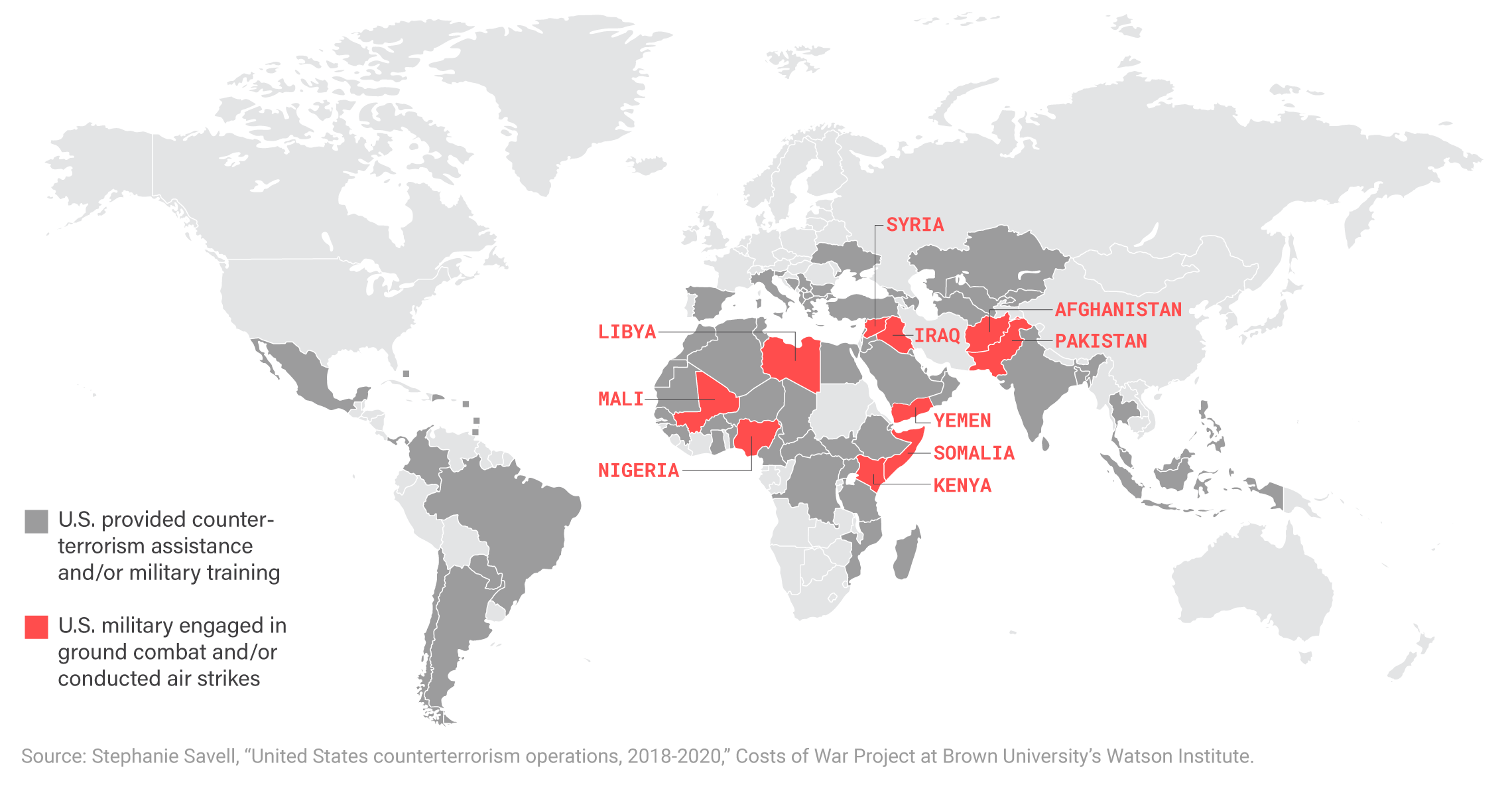

GLOBAL U.S. COUNTERTERROISM OPERATIONS

The U.S. has conducted drone and airstrikes or provided counterterrorism training assistance to at least 79 countries since 2018 as part of the Global War on Terror. The flexibility permitted by a global troop presence has enabled these operations.

Overall, this temptation to use force in the Middle East is a concern when the costs for intervention appear lower than they are in reality due to pre-positioning and pre-paying for logistics capacity. It requires increasing the marginal costs of intervention to encourage greater consideration of the utility of a military option. If the decision to use force is selected following a robust democratic debate on the merits, it will confirm its strategic importance.

Raise logistical costs to reduce temptation

It is precisely because the long-term costs of intervention are so easy to overlook when pre-paying short-term logistical costs that the costs of using force in the Middle East should be made more transparent. That means increasing the cost at the time of intervention. Changing U.S. force posture and logistical infrastructure is prudent. All attendant costs of deployment to that region should be priced in and paid for upfront when deciding to use force to allow more significant consideration of whether it is in the national interest. This will raise the costs for each war in the short term, but it would lower the overall amount spent on wars by avoiding the temptation current logistics help create.

Trying to ensure the true costs of war are considered pre-war to provoke greater consideration of its strategic utility is not new. After Vietnam, there was genuine concern the war was too easy to initiate and escalate without realizing the full costs it would carry. In response, three key proposals tried to make the decision to go to war rely on greater resource commitments and public consideration to determine if an issue was a genuine strategic threat. These were: (1) the so-called Abrams Doctrine that placed combat support roles in the reserves that would mandate activation to deploy,33 (2) the creation of the War Powers Resolution Act that increased the role of Congress and required an authorization to use military force,34 and (3) doctrinal changes such as the Weinberger and Powell Doctrines that tried to make all military operations focus on using overwhelming force to make sure policymakers discussed the resource commitments upfront.35

Unfortunately, U.S. military forays in the Middle East since 2001 have shown that all three checks have eroded since. National Guard and reserve units regularly deploy with an intense operational tempo alongside active-duty units.36 Congress has essentially given a blank check in authorizing force and rarely constrains any action under the War Powers Act.37 And efficiencies in DoD deployments have been prioritized instead of focusing on the doctrine of overwhelming force.38

Deprioritize prepositioning and rapid response

How then can temptation be reduced in the Middle East today? First, de-prioritizing prepositioning and rapid response for the region is necessary. Maintaining the patchwork of bases highlighted above in the region just for unforeseen contingencies related to non-strategic interests only lowers marginal costs for intervention and places these forces in harm’s way. Instead of justifying presence based on reducing future logistical costs, policymakers should prioritize consideration of strategic interest. In the Middle East, this would mean removing remaining U.S. forces in Syria and Iraq, removing the garrisons in Saudi Arabia, and ending logistical support for the war in Yemen. Eliminating or reducing the size of the current logistical hubs in Kuwait, UAE, Qatar, and Bahrain that supply these missions is also required. It would also call for the removal of the Maritime Prepositioning Ships (MPS) deployment at Diego Garcia and potentially also require the repositioning of the Fifth Fleet from the region. If a contingency does arise that mandates U.S. presence, agreements for airlift capacity and naval stationing can be re-activated, but with a more significant lead time.

Fewer forward troops reduce the risk from the temptation to fight for peripheral interests without leaving the United States bereft of striking power. With its sea and airlift to deploy forces, refueling, bombers, missiles, and various naval strike options, the United States will remain in the enviable position of having peerless global power projection capabilities to respond to threats in any region.

Prevent resource sharing between combatant commands

Second, once the basing and pre-positioning of material in the Middle East ends, DoD should further prevent basing and logistics in one regional command to support intervention in other regions. DoD should remove the efficient logistics mindset that developed to allow European bases to support CENTCOM and AFRICOM missions in the region.39 This would also mandate returning U.S. Army Europe and Africa back into U.S. Army Europe only to similarly avoid the ability to use prepositioned forces and material for incursions in Northern Africa. Removing the role of Europe as a logistical waystation would allow bases to focus on their role as strategic assets for deterrence in Europe proper and remove their more destabilizing effect as a critical node of American interventionism in the Middle East. By forcing bases in Europe to focus on their area of responsibility only, they can better concentrate on marshaling power to deter great powers, rather than facilitate punitive raids into the Middle East and North Africa.

Additional benefits of raising logistical costs

Four additional benefits would emerge from increasing logistical costs by reducing U.S. military posture in the Middle East:

- There will be greater incentives for regional diplomacy as a quick U.S. response will not be guaranteed. Reduced U.S. rapid response capabilities will make regional actors focus on diplomatic agreements to balance the region among themselves, knowing U.S. presence cannot be assured.40

- Repeated interventionism for force protection to support the garrisons in the region will be reduced. With fewer vulnerable forces in the region, there will be less reason to station more U.S. forces in the region to protect them.

- There will be a reduction in the moral hazard problem of partners blustering and expecting U.S. support.41 Without U.S. support assured due to permanent basing, destabilizing actions will not have the insurance of U.S. protection, making them less likely to be undertaken. It will also mean that regional actors will more closely compete for U.S. support rather than assuming the United States will have to go along with their misguided policies to maintain basing access.

- Finally, the treadmill of U.S. deployments to the Middle East will stop, allowing for reserve units to serve as an actual strategic, rather than operational, reserve force once again and prepare for contingencies elsewhere. This will enable reserve forces to prioritize strategic threats, and their call-up can again be a possible brake on rapid military action. It will allow the United States to conserve power to augment deterrence of great powers and avoid overstretch in service of peripheral interests.

Existing force posture leads to more instability, not less

Fundamentally, U.S. force posture emphasizing rapid response to the Middle East has had disastrous consequences for U.S. security and interests due to the temptation it has created. Since 1989, the United States has engaged in more than 200 military interventions, with a large percentage of these interventions in the Middle East, Africa, and South Asia as part of the GWOT, well outside core areas of American strategic interest.42 Today, the U.S. continues to be tempted into seemingly endless efforts to mop up ISIS remnants in Syria, keep forces in Iraq to combat Iranian proxies, and support Saudi Arabia and UAE against Houthi rebels from Yemen. The costs in terms of blood, treasure, and civilian deaths are immense.43

The desire for rapid response and the logistics to support it has only placed U.S. forces in harm’s way, antagonized regional actors, and harmed overall military readiness.44 Far from providing any stabilizing role, U.S. presence contributes to greater instability in the region, undermining the purported purpose for its existence.45 It succeeds in allowing rapid response, but rapid response to the instability created by the presence in the first place. Even when it’s clear other strategic priorities demand attention, the inability to desist from continual deployment in the Middle East provides strong evidence policymakers should not discount the temptation costs of an expansive military posture.46

Today, most rapid responses of force in the Middle East are to defend against attacks on currently stationed forces that exist primarily to facilitate their own rapid response. For instance, U.S. service members continue to be placed in dangerous situations in Syria where they face attacks from Iranian proxies and other actors, all to maintain its presence unwisely to support rapid response in the region.47 Without a clear strategic rationale beyond facilitating rapid presence in the region, the United States is essentially paying for the pleasure of over-extending itself and making its troops being vulnerable to attack from actors who otherwise could not reach them.48

Even the advocates of an expansive global military posture admit the problem of temptation can undermine the proposed benefits. For instance, Stephen G. Brooks, G. John Ikenberry, and William C. Wohlforth, advocates of greater forward basing for its stabilizing role, argue that a military posture that enshrines rapid response and global reach will always “increase the opportunity and thus the logical probability of U.S. use of force.”49 Supporting such a posture, they admit, requires accepting as the “cost of doing business” misadventures, like Vietnam, Libya, and Iraq.

While blunders of the magnitude of Iraq and Vietnam every few decades are a significant price to pay, unfortunately, these are not the only costs. The legacy of the infrastructure created to support these misadventures has a long shadow when maintained to deal with future instability directly created by the original interventions themselves. If future interventions are justified based on dealing with the instability created in large parts from the misadventures in the first place, the costs of a global military posture are much higher than advocates claim.50 U.S. basing posture then is justified by fighting instability in a region their own presence helps to create.

The unfortunate outcome of the current posture is that it makes military intervention falsely appear as a cheap tool and easy solution to various crises without considering this posture's full cost. Rather than relying on self-sagaciousness to avoid missteps and disasters, creating logistical barriers to limit rapid military response will encourage greater deliberation and consideration of its true worth and utility for various issues.

Indeed, the temptation problem will continue to exist as long as the United States remains a great power with extensive power projection capabilities, but that does not mean it should make interventions easier to start. Instead, making the price of additional use of force more transparent by making logistics for intervention more costly and stored at a further distance is beneficial. Making military force more costly to use in the region will increase the interrogation upfront if other tools are better suited to advance U.S. interests exist. If the logistical lift to carry out intervention to defend a territory abroad or resist a different expansionary power serves U.S. interests, then the cost to deploy from home can be debated and confirmed during the mobilization period, providing additional verification it is indeed a vital national interest. Being able to send force rapidly across the globe is an impressive feat the U.S. accomplished. Having proven able to do so, now is the time for the United States to take the even more remarkable step to limit this capability.

Endnotes

1 Department of Defense, “Statement by Secretary of Defense Lloyd J. Austin III on the Initiation of a Global Force Posture Review,” February 4, 2021, https://www.defense.gov/News/Releases/Release/Article/2494189/statement-by-secretary-of-defense-lloyd-j-austin-iii-on-the-initiation-of-a-glo/.

2 Kimberly Dozier, “Biden Wants to Keep Special Ops in the Mideast. That Doesn’t Mean More ‘Forever Wars,’ His Adviser Says,” Time, September 23, 2020, https://time.com/5890577/biden-middle-east-special-operations-forces/.

3 Stephen G. Brooks, G. John Ikenberry, and William C. Wohlforth, “Don’t Come Home, America: The Case Against Retrenchment,” International Security 37, no. 3 (2012): 7–51.

4 Renanah M. Joyce and Brian Blankenship, “Access Denied? The Future of U.S. Basing in a Contested World,” War on the Rocks, February 1, 2021, https://warontherocks.com/2021/02/access-denied-the-future-of-u-s-basing-in-a-contested-world/.

5 This force posture “requires military capacity easily used for other ends. Forces stationed abroad in the name of primacy enable wars justified by humanitarianism, liberalism, and other goals outside primacy’s logic.” Campbell Craig et al., “Debating American Engagement: The Future of U.S. Grand Strategy,” International Security 38, no. 2 (2013): 188.

6 Kenneth N. Waltz, “A Strategy for the Rapid Deployment Force,” International Security 5, no. 4 (1981): 49.

7 For more on discounting long-term costs and time horizons, see Ronald R. Krebs and Aaron Rapport, “International Relations and the Psychology of Time Horizons,” International Studies Quarterly 56, no. 3 (2012): 530–543.

8 John Diamond and Washington Bureau, “In Farewell, Albright Jabs at Powell,” Chicago Tribune, January 10, 2001, https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/ct-xpm-2001-01-10-0101100176-story.html.

9 Justin Logan, “The Case for Withdrawing from the Middle East,” Defense Priorities, September 30, 2020, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/the-case-for-withdrawing-from-the-middle-east.

10 “THE 2000 CAMPAIGN; 2nd Presidential Debate Between Gov. Bush and Vice President Gore,” New York Times, October 12, 2000, https://www.nytimes.com/2000/10/12/us/2000-campaign-2nd-presidential-debate-between-gov-bush-vice-president-gore.html; John Whitesides, “Obama Says He Opposed Iraq War from Start,” Reuters, February 11, 2007, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-politics-obama/obama-says-he-opposed-iraq-war-from-start-idUSN0923153320070212.

11 “Transcript: Donald Trump’s Foreign Policy Speech,” New York Times, April 27, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/28/us/politics/transcript-trump-foreign-policy.html; Bill Barrow, “Biden Promises to End ‘Forever Wars’ as President,” Military Times, July 11, 2019, https://www.militarytimes.com/news/pentagon-congress/2019/07/11/biden-promises-to-end-forever-wars-as-president/.

12 “United States Counterterrorism Operations 2018–2020,” Abstract. Costs of War Project, https://watson.brown.edu/costsofwar/papers/2021/USCounterterrorismOperations.

13 Dakota L. Wood, ed., “2022 Index of US Military Strength,” Heritage Foundation, 2022, 152, https://www.heritage.org/sites/default/files/2021-09/2022_IndexOfUSMilitaryStrength.pdf.

14 Tyler F. Hacker, “Defense Primer: Department of Defense Pre-Positioned Materiel,” Congressional Research Service, December 9, 2020, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF11699/2.

15 Kathleen J. McInnis and Brendan W. McGarry, “United States European Command: Overview and Key Issues,” Congressional Research Service, August 4, 2020, https://sgp.fas.org/crs/natsec/IF11130.pdf.

16 Wood, ed., “2022 Index of US Military Strength,” 114–116.

17 David Blagden and Patrick Porter, “Desert Shield of the Republic? A Realist Case for Abandoning the Middle East,” Security Studies 30, no. 1 (2021): 5¬–48.

18 William E. Odom, “The Cold War Origins of the US Central Command,” Journal of Cold War Studies 8, no. 2 (2006): 52–82.

19 Jim Garamone, “Biden Approves Global Posture Review Recommendations,” DoD News, November 29, 2021, https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/2856053/biden-approves-global-posture-review-recommendations/.

20 Becca Wasser, “Drawing Down the U.S. Military Responsibly,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, May 18, 2021, https://carnegieendowment.org/2021/05/18/drawing-down-u.s.-military-responsibly-pub-84527. Even among advocates of drawing down forces in the Middle East, the idea that infrastructure for rapid response should remain is attractive.

21 Michael J. Lostumbo, et al., “U.S. Overseas Military Posture: Relative Costs and Strategic Benefits,” (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2013) 1, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_briefs/RB9708.html.

22 Ryan Henry, “Transforming the U.S. Global Defense Posture.” Naval War College Review 59, no. 2 (2006): 25–26.

23 Karl P. Mueller, ed., “Precision and Purpose: Airpower in the Libyan Civil War,” (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2015), 120, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR676.html.

24 Mueller, “Precision and Purpose: Airpower in the Libyan Civil War,” 94. Ironically, the 480th Expeditionary Wing based in Germany was already preparing to deploy to Afghanistan when they were transferred to the Libya mission.

25 Mueller, “Precision and Purpose: Airpower in the Libyan Civil War,” 26.

26 Thom Shanker and Eric Schmitt, “Seeing Limits to ‘New’ Kind of War in Libya,” The New York Times, October 21, 2011, https://www.nytimes.com/2011/10/22/world/africa/nato-war-in-libya-shows-united-states-was-vital-to-toppling-qaddafi.html.

27 Jeffrey Goldberg, “The Obama Doctrine,” Atlantic, April 26, 2016, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2016/04/the-obama-doctrine/471525/.

28 Kenneth N. Waltz, “A Strategy for the Rapid Deployment Force,” International Security 5, no. 4 (1981): 50.

29 Similar critiques have been discussed with the U.S. Army’s new multi-domain operational concept where their “obsession with speed and duration is a strategic miscalculation that…cedes the nation’s geostrategic advantages.” Christopher Parker, “Rushing to Defeat: The Strategic Flaw in Contemporary U.S. Army Thinking,” Strategy Bridge, July 6, 2020, https://thestrategybridge.org/the-bridge/2020/7/6/rushing-to-defeat-the-strategic-flaw-in-contemporary-us-army-thinking.

30 Kenneth Waltz, Foreign Policy and Democratic Politics: The American and British Experience (New York: Longmans, 1967).

31 Bernard Brodie, “The Development of Nuclear Strategy,” International Security 2, no. 4 (1978): 80–81.

32 John Haltiwanger, “Just 13% of Americans Would Support U.S. Military Going to War Over Saudi Oil Field Attack,” Business Insider, September 18, 2019, https://www.businessinsider.com/13-percent-americans-support-us-military-response-saudi-oil-attack-2019-9; Resources stationed in UAE, Syria, and elsewhere were used to reposition forces in the country without much debate at home about the potential consequences of re-starting U.S. deployments in Saudi Arabia. Jared Malsin, “U.S. Forces Return to Saudi Arabia to Deter Attacks by Iran,” Wall Street Journal, February 26, 2020, https://www.wsj.com/articles/u-s-forces-return-to-saudi-arabia-to-deter-attacks-by-iran-11582713002.

33 Lewis Sorley, “Creighton Abrams and the Active-Reserve Integration in Wartime,” Parameters 21, no. 2 (Summer 1991): 35–50; While it is now unclear what the actual intent of the initial total force policy was, decisionmakers within the U.S. military have internalized it to mean the nation goes to war only if the Guard and Reserve are mobilized to join the fight.

34 Matthew C. Weed, “The War Powers Resolution: Concepts and Practice,” Congressional Research Service, March 8, 2019, https://sgp.fas.org/crs/natsec/R42699.pdf.

35 Patrick Porter “The Weinberger Doctrine: A Celebration,” Infinity Journal 3, no. 3 (Summer 2013): 8–11, https://www.militarystrategymagazine.com/article/the-weinberger-doctrine-a-celebration/.

36 Christopher M. Schnaubelt, et al., Sustaining the Army’s Reserve Components as an Operational Force, (Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 2017), https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR1400/RR1495/RAND_RR1495.pdf.

37 Daniel DePetris, “Checks and Balances on War Powers,” Defense Priorities, April 21, 2021, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/checks-and-balances-on-war-powers.

38 Christopher Preble, “The Powell Doctrine’s Wisdom Must Live On,” Atlantic Council, October 18, 2021, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/the-powell-doctrines-wisdom-must-live-on/.

39 The military hospitals that support operations in the Middle East should remain, at least until all operations and bases in the region are removed.

40 Thomas Grove, Stephen Kalin, and Summer Said, “Fear of Iran, Shrinking U.S. Role in Middle East Push Rivals Together,” Wall Street Journal, December 13, 2021, https://www.wsj.com/articles/israeli-u-a-e-leaders-meet-amid-flurry-of-middle-east-diplomacy-11639413346.

41 For a discussion of this problem, see: Barry R. Posen, "Pull Back: The Case for a Less Activist Foreign Policy,” Foreign Affairs 92, no. 1 (2013): 122–123.

42 Barbara Salazar Torreon and Sofia Plagakis, “Instances of Use of United States Armed Forces Abroad, 1798–2021,” Congressional Research Service, 2021, https://sgp.fas.org/crs/natsec/R42738.pdf.

43 Amanda Macias, “America Has Spent $6.4 Trillion on Wars in the Middle East and Asia Since 2001, a New Study Says,” CNBC, November 20, 2019, https://www.cnbc.com/2019/11/20/us-spent-6point4-trillion-on-middle-east-wars-since-2001-study.html; Neta C. Crawford and Catherine Lutz, “Human Cost of Post-9/11 Wars,” Costs of War Project, September 2021, https://watson.brown.edu/costsofwar/figures/2021/WarDeathToll.

44 Gil Barndolar, “Global Posture Review 2021: An Opportunity for Realism and Realignment,” Defense Priorities, July 12, 2021, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/global-posture-review-2021.

45 Mike Sweeney, “Considering the ‘Zero Option’,” March 3, 2020, Defense Priorities, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/considering-the-zero-option. U.S. forces in the region end up radicalizing and serving as targets for extremist organizations, thereby requiring greater deployments to protect these forces and furthering a cycle of instability.

46 David Blagden and Patrick Porter, “Desert Shield of the Republic? A Realist Case for Abandoning the Middle East,” Security Studies 30, no. 1 (2021): 5–48; Similarly, the oil justifications for maintaining a U.S. presence in the region continue to wane. See Justin Logan, “The Case for Withdrawing from the Middle East,” Defense Priorities, September 30, 2020, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/the-case-for-withdrawing-from-the-middle-east.

47 Jared Malsin and Nancy A. Youssef, “U.S. Soldiers Injured in Syria After Shelling Attack,” Wall Street Journal, April 7, 2022, https://www.wsj.com/articles/u-s-soldiers-injured-in-syria-after-shelling-attack-11649326303.

48 Natalie Armbruster, “Apply the Logic of the Afghanistan Withdrawal to Syria,” Defense Priorities, March 7, 2022, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/apply-the-logic-of-the-afghanistan-withdrawal-to-syria.

49 Stephen G. Brooks, G. John Ikenberry, and William C. Wohlforth. “Don’t Come Home, America: The Case Against Retrenchment,” International Security 37, no. 3 (2012): 31; As Brooks and Wohlforth subsequently admit, “in a world in which the United States retains its overwhelming military preeminence as its economic dominance slips, the temptation to overreact to perceived threats will grow-even as the margin of error for absorbing the costs of the resulting mistakes will shrink.” Stephen G. Brooks and William C. Wohlforth, “The Once and Future Superpower: Why China Won’t Overtake the United States,” Foreign Affairs 95, no. 3 (2016): 104.

50 Most uses of force in the region directly follow a previous intervention in the same country. This illustrates the stabilizing benefits are directly overstated. See Torreon and Plagakis, “Instances of Use of United States Armed Forces Abroad, 1798–2021.”