Key points

NATO’s tactical nuclear weapons are dangerous relics. Whereas during the Cold War tactical nuclear weapons were believed to help bolster deterrence, today they serve no functional purpose other than to unnecessarily escalate a local crisis—such as in the Baltic states—into a potential strategic calamity.

Operationally, the 150 B61 bombs the United States still deploys in Europe are effectively useless. They are basic gravity (or free-fall) bombs whose delivery would require a non-stealth plane like the F-16 or Tornado strike aircraft to fly into the teeth of Russia’s advanced air defense capabilities where it would face certain destruction well before reaching its target.

Removing U.S. B61s from Europe would not be a panacea for NATO-Russia relations, but it could be a first step in reestablishing a constructive dialogue with Moscow, one that would cost the alliance nothing in actual warfighting capability.

Russia is an illiberal regime with capable military forces within its own region. But it is not “the Soviet Union 2.0.” Russia does not pose the same global, existential threat it once did. In dealing with Moscow, there is thus no reason to perpetuate nuclear policies from another era that were designed to address a significantly greater challenge.

Tactical nuclear weapons: unwelcome return1

In 1953, Robert Oppenheimer likened the United States and the Soviet Union to two scorpions locked in a bottle—"each capable of killing the other, but only at the risk of his own life."2 That analogy should not obtain today. America and Russia are no longer equals, nor should they be seen as "locked" into conflict. The ideological underpinnings of the Cold War and its zero-sum nature are not relevant to current disputes between the two nations. Promulgating nuclear policies created and designed for that era serves no useful purpose.

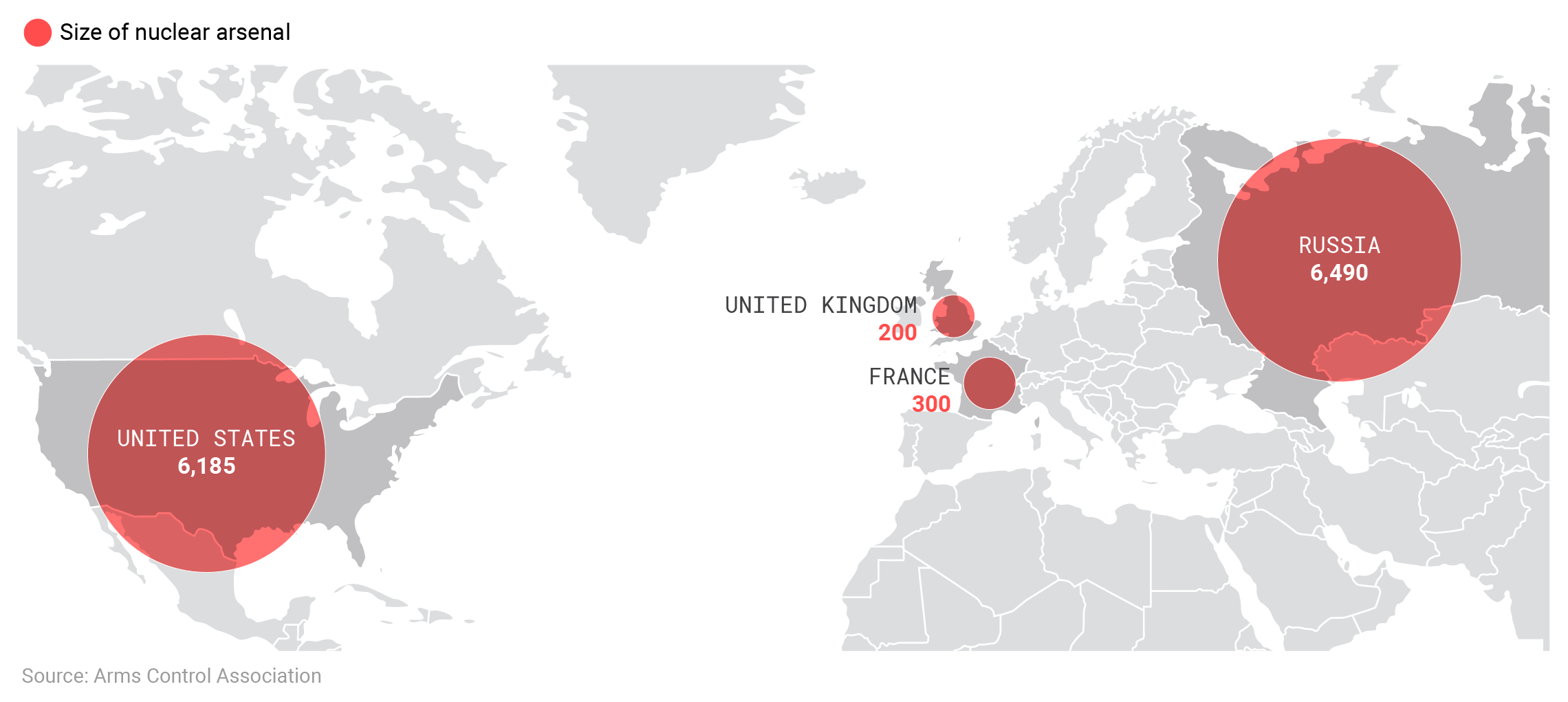

Nuclear arsenals of the U.S., Europe, and Russia

The U.S. and Russia currently have more than 6,000 nuclear weapons each, including stockpiled warheads and retired warheads awaiting dismantlement.

The United States has more concerns—both at home and abroad—than its differences with Russia. Fixating on Russia as a peer competitor—and particularly a nuclear one—is a needless, self-fulfilling prophecy, one that distracts the United States from other concerns. Furthermore, it risks an unnecessary and potentially catastrophic clash over minor interests. Nowhere is this more obvious than in current debates about modernizing NATO's nuclear weapons and their possible applicability to a crisis involving the Baltic states.

Current plans to enhance U.S. tactical nuclear holdings in line with the findings of the 2018 Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) are therefore a mistake.3 Rather than fielding new and upgraded weapons, the United States should unilaterally withdraw its remaining force of B61 bombs from Europe.

In the specific instance of the Baltic states, tactical nuclear forces are unlikely to aid their defense without devastating large portions of their territory and possibly inciting a strategic nuclear exchange. They will not effectively compensate for Russia's local conventional superiority in northeast Europe. Nor will tactical nuclear weapons inherently bolster deterrence, contrary to the arguments of their proponents.4

Rather than enhanced nuclear planning, NATO needs a new mechanism for strategic dialogue with Russia. Throughout the Cold War, such mechanisms existed—whether in the form of the Mutual and Balanced Force Reduction (MBFR) talks of the 1970s or the Conventional Forces in Europe (CFE) negotiations of the 1980s. Although the latter produced a landmark treaty, the former nominally produced nothing. But the dialogue itself was useful in managing the Cold War standoff and likely laid the diplomatic foundation for more concrete steps in the 1980s, such as the CFE Treaty and the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty.

A similar approach is required now. Removal of the B61s could be a literal peace offering to promote such a discussion, one that would cost NATO nothing in terms of actual warfighting capability. As will be discussed below, the B61s have practically no utility due to the constraints on their employment and their severe operational limitations.

The early days of Armageddon

To understand why the B61s remain an issue today, consider the history of tactical nuclear weapons since the 1950s. The concept of "battlefield nukes" was embraced early by U.S. planners who saw the systems as a means to compensate for U.S. conventional weakness in both Asia and Europe. Confronted with the early defeats of the Korean War and the daunting challenge of defending Western Europe against a numerically superior Red Army, tactical nuclear weapons seemed an obvious answer.5 Their budgetary savings (compared to large standing military forces) also played a role as both the Truman and Eisenhower administrations were loath to overextend the United States financially in support of its defensive commitments.

Eisenhower in particular embraced the frugality of tactical nuclear weapons, accepting major reductions in conventional forces in favor of a doctrine of massive retaliation.6 As part of this, a dizzying array of tactical nuclear systems were deployed to Asia and Europe, including short-range missiles, gravity bombs, artillery shells, land mines, and even nuclear-armed bazookas. These were backed by additional tactical nuclear weapons at sea on U.S. Navy ships and submarines. These deployments, coupled with liberal preauthorization orders for many tactical systems, made the potential for unintentional nuclear use exceptionally high in the 1950s.7

From the Soviet side, the cost-saving aspect of nuclear weapons also held great appeal. Nikita Khrushchev saw nuclear weapons as a means of freeing up badly needed funding for other aspects of the Soviet economy.8 To drive home his point, he disbanded the Ground Forces (heroes of World War II) as an independent service and subordinated them to the Strategic Rocket Forces; the army's budget was gutted accordingly.9

Each side's early plans for the use of tactical nuclear weapons were ghoulish, as illustrated by what is known of major exercises from that era. In NATO, the most infamous was Operation Carte Blanche, a 1955 simulation that gamed out the use of tactical nuclear weapons to halt a Soviet invasion. In the simulation, 355 nuclear weapons were deployed by NATO to stop the Soviet offensive, with most strikes taking place over German territory. Analysts estimated 1.5 million Germans would have been killed outright, with another 3.5 million wounded in the process of "defending" their country with nuclear weapons.10

For the Soviets, a command post exercise in 1961 similarly projected devastating casualties for a plan that would see the Warsaw Pact essentially bomb its way to Paris. Codenamed "Buria," the wargame explicated Soviet plans for a response in the event of a renewed crisis over West Berlin. In the simulation, the Soviets employed 1,000 tactical nuclear weapons and anticipated NATO retaliating with up to 1,200 of its own. Despite the massive death and destruction caused by detonating a combined 2,200 nuclear devices over the European landscape, the Soviets still expected a decisive victory: Warsaw Pact forces would reach the French capital and then Calais within ten days, regardless of the Armageddon unfolding around them.11

Enter flexible response

The 1960s saw a somewhat more enlightened approach from both sides. In Moscow, Khrushchev's ouster in 1964 allowed for renewed debate on the relationship between conventional and nuclear forces, as well as the reinstitution of the Ground Forces as an independent command. As the Soviets were presumed to be the ones with the conventional advantage for most of the 1960s and 1970s, they saw nuclear use as detrimental in most instances. Significantly, they worried over their ability to control escalation once nuclear employment was initiated—by either side.12 As the 1970s progressed into the 1980s, Soviet military thinkers such as Marshal Nikolai Ogarkov began to conceptualize applications of advanced conventional weapons mated to enhanced sensors—the reconnaissance-strike complex—that could produce effects similar to tactical nuclear weapons, perhaps obviating their need entirely.13

In the United States, the Kennedy administration sought options beyond the all-or-nothing strategy of massive nuclear retaliation, especially in the event of a small-scale or limited conflict. Influenced in part by the thinking outlined in Maxwell Taylor's 1959 book, The Uncertain Trumpet, the Kennedy administration wanted to move the United States away from a choice between resort to total nuclear war on the one hand or acquiescence to low-level aggression on the other.14

At the same time, European nations—spurred in part by exercises like Carte Blanche—were seeking means of defending their countries without the immense devastation that came with tactical nuclear employment. These trends led to increased emphasis on developing NATO's conventional capabilities while still retaining the possibility for tactical nuclear use. This policy, based on a range of potential responses to any aggression, was known as flexible response.15

NATO also began to institutionalize thinking and consultation on nuclear issues. Predelegated authority for use of U.S. tactical nuclear weapons was rescinded in favor of "dual key" structures that provided host states a veto. European members would operate some of the delivery vehicles for tactical nuclear weapons while the United States retained final say over the release of the weapons themselves. In theory, the United States could authorize the weapons to be used and the host country could decline.

These procedures persist to this day with the residual B61 inventory. Although commonly referred to as "NATO's tactical nuclear weapons," the B61s are wholly owned by the United States, with their employment requiring release authorization from the U.S. president. Delivery of the weapons are tasked to the host country who operate what are referred to as Dual Capable Aircraft (DCA)—fighter-bombers certified to perform nuclear delivery in addition to their traditional conventional roles.

The Presidential Nuclear Initiatives

As the Cold War wore on, both sides seemed to have decreased impetus to use tactical nuclear weapons. From the Soviet side, greater faith in conventional capabilities discouraged resort to nuclear weapons unless absolutely necessary. From NATO's side, growing concerns over the collateral damage inflicted by battlefield weapons pushed for limits on their employment and the implementation of policies that, at least theoretically, allowed for the possibility of warfighting without nuclear use. Still, actual stockpiles remained high and planning for employment continued. NATO's tactical nuclear inventory reached a peak of between 7,000 and 8,000 weapons in the 1970s, and by the end of the Cold War the Soviet Union may have had as many as 22,000 tactical weapons.16 This class of weaponry consistently eluded arms control efforts, unlike strategic and intermediate-range systems.

Nuclear arsenals of the U.S. and USSR/Russia since 1945

The United States and the USSR together had more than 60,000 nuclear warheads during the Cold War. Today, the U.S. and Russia each has around 4,000, not including retired warheads awaiting dismantlement.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall, a massive reduction in tactical nuclear weapons took place. Significantly, it was the result of unilateral U.S. action. In September 1991, President George H.W. Bush announced the United States was withdrawing almost all of its tactical nuclear weapons from the field as part of a series of changes to the nation’s nuclear posture stemming from the end of the Cold War.17 The United States was acting of its own volition, but encouraged the Soviet Union to respond in kind. Subsequent statements by Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev and Russian President Boris Yeltsin (following the USSR’s break up) pledged reciprocal reductions focused on tactical nuclear weapons. Collectively, these measures were known as the Presidential Nuclear Initiatives (PNIs).

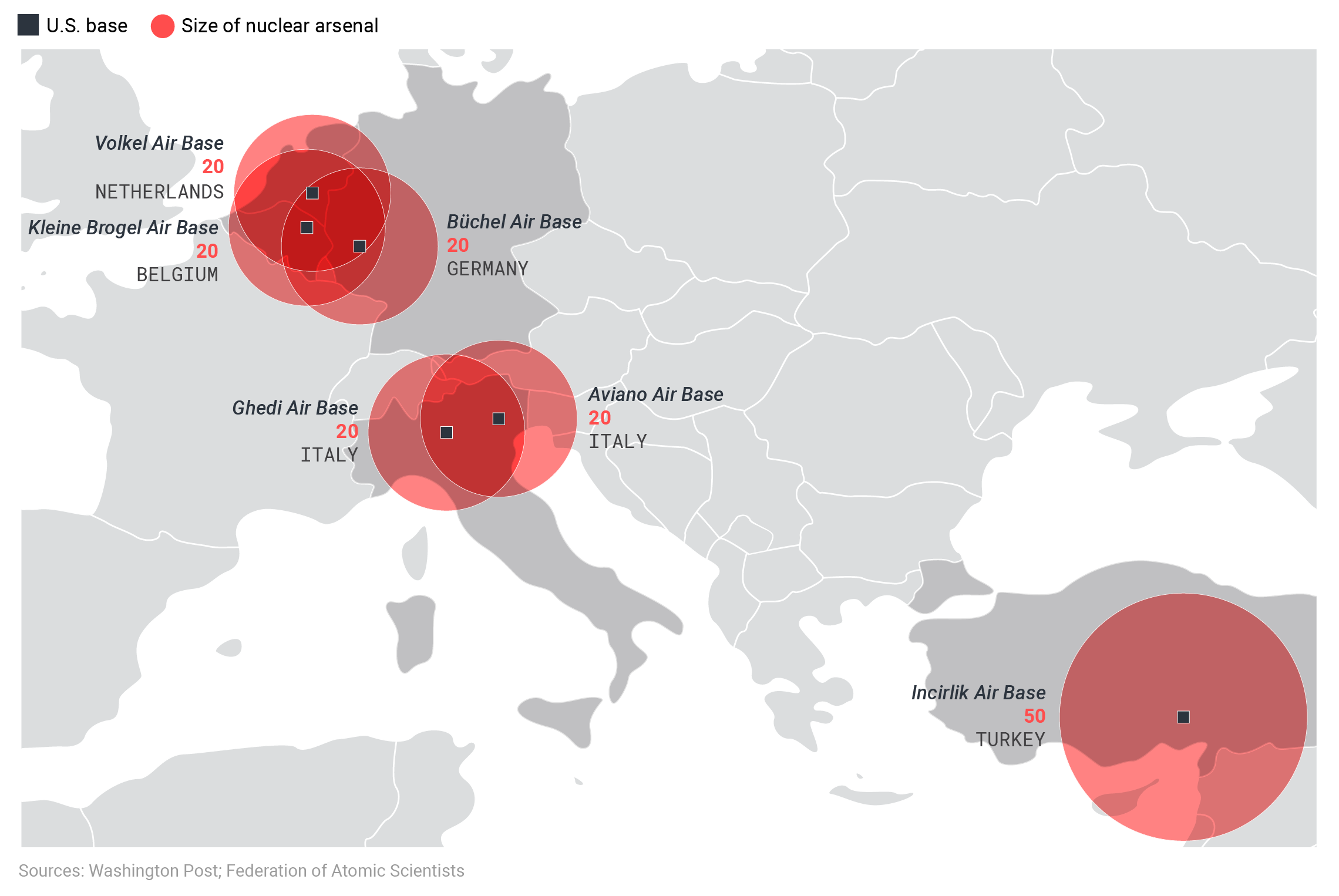

Although the United States withdrew (and subsequently destroyed) its short-range nuclear-armed missiles and nuclear artillery shells from Europe under the PNIs, it chose to retain its force of air-delivered nuclear bombs. Reductions have been made in the ensuing 30 years in terms of the number of bombs and storage sites.18 But the United States today still deploys an estimated 150 B61s in Europe at six facilities spread over five countries: Belgium, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, and Turkey.19

Are tactical nuclear weapons still necessary?

A confluence of factors has refocused attention on NATO's B61 inventory. An important aspect has been concerns over the defensibility of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. A series of RAND wargames conducted in 2014 and 2015 revealed severe shortcomings in the alliance's defenses in the Baltic region and suggested Russian forces could easily reach Tallinn and Riga within 60 hours.20 Mated with Russia's recent history of using military force against its neighbors—including the 2008 August War against Georgia, the 2014 seizure of Crimea, and its ongoing support to the Donbas insurgency—speculation arose NATO could only defend the Baltic region through nuclear deterrence.21

At the same time, more aggressive interpretations of Russia's emerging military doctrine on nuclear employment stoked fears it might use nuclear weapons to intimidate or even attack the Baltic states or other NATO members.22 It is worth noting here that Russia never completely fulfilled its obligations under the PNIs.23 To the contrary, it has invested heavily in modernizing this class of weaponry and has been frustratingly opaque about the numbers of tactical weapons it now maintains. Estimates from inside and outside government have pegged Russia's inventory at between 1,830 and 2,000 operational tactical weapons, though some analysts suggest the figure could be closer to 1,000.24 But even at this lower number, Russia massively outguns NATO and the United States in terms of the sheer number of tactical nuclear weapons it could employ.

The Soviet Union long had an official position of No First Use—i.e., it would never be the one to initiate a nuclear conflict. This was generally regarded as propaganda and not truly binding.25 When Russia abandoned this pledge in 1993, it essentially adopted the same position on the issue as the United States. However, Russian military doctrine—beginning in 2000—expanded the circumstances under which nuclear weapons could be used, to include responses to conventional attack. For some, this development, coupled with the abandonment of No First Use, led to the prospect of Russia initiating nuclear use in a conventional conflict. Some analysts even interpreted Russia's intention as proposing to use nuclear weapons to terminate a conventional war on favorable terms.26 This has come to be known as "escalate to de-escalate" in the West, although the Russians themselves never use that terminology.27

There is no definitive evidence this is the intent of Russian doctrine, however.28 Indeed, subsequent iterations actually narrowed the circumstances under which Russia would use nuclear weapons.29 For example, the 2000 version of the doctrine stated nuclear weapons could be used in the response to conventional attack "in situations deemed critical to the national security of the Russian Federation," a fairly open-ended determination.30 Yet the 2010 doctrine replaced that phrase with wording that suggested nuclear weapons would only be used if the very existence of the Russian state was in danger.31 Despite this, fear Moscow will use tactical nuclear weapons to threaten or intimidate its neighbors persists.32 Most significantly, "escalate to de-escalate" is accepted as gospel in the 2018 Nuclear Posture Review, which mentions it explicitly as Russia's policy.33 Not surprisingly then, the NPR called for modernizing U.S. tactical nuclear weapons, in a bid to give the United States a tit-for-tat deterrence option at the substrategic level.34

Two years after the NPR's release, this modernization is well underway. An improved version of the B61—the Mod 12—is in production, though it has encountered technical delays.35 Although some of these bombs will be assigned to the U.S. domestic arsenal, they will also serve as replacements for the existing stock of B61s in Europe. A tactical nuclear warhead has also been deployed at sea for the first time in three decades—the W76-2, a low-yield (5 kiloton) warhead mated to the Trident submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM).36 A submarine-launched cruise missile for tactical nuclear delivery is also in development.37

But is this wise? Given the risks—and costs—associated with a reintroduction of sea-launched tactical nuclear weapons and upgrades to air-delivered bombs, more careful consideration should be given to these steps—particularly when it comes to the European theater. Tactical nuclear weapons do not enhance deterrence, nor would they compensate for conventional weakness in a Baltic contingency.

Tactical nuclear weapons don’t enhance deterrence

The logic behind the NPR's expansion of U.S. substrategic capabilities rests heavily on fears over Russian tactical capabilities. Two main concerns are cited: Russian threats to use tactical nuclear weapons to coerce NATO or actual employment by Russia of limited nuclear strikes to achieve military and political objectives.38 The goal of fielding improved U.S. tactical capabilities is thus to enhance deterrence, or as one participant in the NPR phrased it, "to reduce Russian confidence in their coercive escalation strategy."39

In short, the more tactical options the United States has, the more credibly it can threaten to match Russia's own tactical use (whether implied or actual) and thereby deprive Russia of the coercive benefit of its tactical nuclear weapons.

But this line of reasoning founders on the obvious fact that the United States already has a substantial strategic arsenal. Russian tactical use against NATO forces risks inciting a broader nuclear exchange. Even though these weapons might be "small" relative to larger strategic bombs, tactical nuclear weapons still possess significant destructive capability, as well as the moral weight of breaking the nuclear taboo.

This calls to mind the oft-repeated maxim among many senior U.S. military officers that there is no such thing as a "tactical" nuclear weapon.40 All nuclear use automatically becomes strategic insofar as it raises the prospect of uncertain retaliation by the opposing nuclear power. As such, the weight of deterrence falls on U.S. strategic forces; tactical nuclear weapons are not specifically needed to enhance deterrence.

U.S. nuclear weapons in Europe

The United States has dozens of nuclear weapons located at military bases in Belgium, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, and Turkey.

In this light, it is also worth revisiting Russia’s numerical superiority in tactical nuclear weapons. Yes, Russia might have as much as a 13-to-1 advantage in substrategic warheads within the European theater. But how many of them can they use before it triggers a strategic response? Fifty? Five? Certainly not the whole 2,000 that DoD believes is in its arsenal.41 As such, because the United States retains robust strategic forces, it does not need to match Russia bomb for bomb at the tactical level. Long before it exhausts its tactical stockpile, Russia would have sparked a strategic nuclear exchange.

The uncertainty of escalation management

In theory, tactical nuclear weapons could fill a gap between conventional forces and strategic nuclear weapons use—as the architects of the NPR likely intend—if it could be absolutely assured that their use would remain limited in scope. But this simply is not the case in the real world. Once a tactical nuclear weapon is employed, there is no way to determine decisively how an adversary will view its effects and whether it will decide to retaliate with tactical- or strategic-level forces.

The results of recent wargames conducted by RAND on nuclear use in a Baltic contingency are illuminating in this regard.42 In one excursion, NATO initiates tactical nuclear use, targeting a mobile Russian air defense system, just inside the Latvian border. In response, Russia retaliates with nuclear strikes of its own against F-22 and F-35 bases in Western Europe.43 Significantly, NATO’s nuclear use was not seen by game participants as impacting the Russian advance, yet it opened the door for Moscow to launch its own nuclear strikes, arguably achieving more important battlefield effects by depriving NATO of its qualitative advantage in tactical aircraft.

There is also another dimension at play, though. In the game, Russia uses "moderately sized" warheads of 50 kilotons in response to NATO's initial battlefield use of low-yield warheads.44 This illustrates how hard it can be to control escalation once the nuclear threshold is breached. In short, because one side uses weapons of a specific yield, there is no guarantee the opposing side will restrict itself to that same limit—assuming that the yield of nuclear detonations can even be gauged accurately midbattle.

Just as importantly, the theorized Russian counterstrikes quickly blurs the border between "tactical" and "strategic." Russia's attacks are nominally executed to deprive the alliance of warfighting capabilities (its F-22s and F-35s), but there also would be significant casualties that carry their own consequences. Using Aviano in Italy and Ramstein in Germany as examples, projected fatalities for each base were estimated to be 5,000 dead with another 15,000 wounded.45 Presumably some of these are U.S. service personnel and their dependents. Although the RAND game does not address this directly, it is worth wondering if the U.S. response at that point would not be strategic in nature due to such large casualties. Has Russia crossed a threshold?

The inability to answer that question definitively shows the folly of believing that tactical nuclear war can be inherently limited. Though the RAND wargame is just a tabletop exercise, it shows that once the nuclear taboo is broken, there is no certitude about what happens next. All the more reason to avoid making tactical use more likely, as the modernization efforts under the NPR do. Tit-for-tat deterrence capabilities make no sense if there is no guarantee the other side will abide by the perceived rules of what constitutes “acceptable” use.

The preceding example highlights another challenge for deterrence in Europe now as opposed to during the Cold War era. Whereas Russia can target NATO territory without directly striking the U.S. homeland, a reverse option is not available to the alliance. When the Warsaw Pact existed, its territory provided something of a strategic neutral zone where NATO could conceivably employ nuclear forces to demonstrate resolve in an effort to halt or deter Soviet aggression.46

One can debate, in retrospect, whether a nuclear detonation over Poland would have truly given Moscow pause (or just encouraged retaliation), but it is worth acknowledging that the geography of Cold War Europe made such a strike possible. NATO could use nuclear weapons without targeting Soviet territory proper, a move which carried the risk of an immediate strategic response.

That is no longer the case. As discussed in greater detail below, it is nearly impossible to find viable nuclear targets in a Baltic contingency unless strikes on Russian territory are willing to be considered, which they should not. That limitation is another factor undermining effective tactical nuclear use by NATO, which in turn further weakens whatever deterrence value substrategic weapons are said to have.

Extended deterrence is compromised in the Baltic region

The deterrence value of tactical nuclear weapons is also undercut in the specific instance of the Baltic region by the imbalance of interests between Russia and the United States. Would Russia realistically believe the United States was willing to employ tactical nuclear weapons—potentially risking escalation to a strategic exchange—to defend countries in which the United States could be said to have minor interests at best? If not, U.S. tactical weapons rapidly become an empty bluff.

This cuts to the heart of the challenge of making effective nuclear guarantees. A nuclear-armed opponent like Russia must believe that the United States is willing to risk its own territory and population to protect those it has pledged to defend. As Henry Kissinger once put it, the credibility of American nuclear guarantees is thus based on the perception of its willingness to commit "mutual suicide."47

During the Cold War, this prospect was embodied in the question posed by General Charles de Gaulle—whether the U.S. president was really willing to sacrifice Chicago for Lyon. Or, as Joshua Shifrinson has updated the query for the twenty-first century, is the United States willing to trade Toledo for Tallinn?48

The response is almost certainly a negative one. In the 1990s, perhaps overly ambitious hopes were placed on the prospect of NATO and EU membership encouraging and solidifying democratic trends in Central and Eastern Europe.49 Two decades on, the overall results are mixed. But, by and large, the three Baltic states have vindicated the alliance’s faith. They are strong democracies who have effectively handled the difficult question of incorporating the large Russophone minorities left on their territory after the breakup of the USSR.50 All three states also are consistently at or near the 2 percent GDP defense spending goal set for NATO, unlike most European members.51 From this perspective, the Baltic states can be counted as success stories.

The proximity of Eastern Europe to Russia

Eastern Europe’s proximity to Russia and limited economic and security importance to the U.S. present a challenge in making effective nuclear guarantees.

That said, they simply are not worth fighting a nuclear war over. Certainly, losing the Baltic states to Russia would have consequences for the alliance and for the legitimacy of U.S. security guarantees. But NATO can survive the loss of the Baltic states and still function as a defensive alliance. It would not be a death blow to NATO equivalent to the Red Army sweeping across West Germany and the Low Countries at the height of the Cold War.

U.S. security and vital interests would also not be irretrievably harmed by a defeat in the Baltics—provided the conflict stays conventional. The United States suffered and survived a devastatingly painful loss in Vietnam and still went on to win the Cold War. It has engaged in several wars in the Middle East over the last twenty years, with questionable results and high costs, and yet it remains the preeminent global power. The outcome of a Baltic war will not make or break American strategic relevancy—so long as the conflict does not go nuclear.

Deploying additional and more capable tactical nuclear weapons thus does not make sense. They will not enhance deterrence and risk unnecessarily escalating a crisis into the one situation where a Baltic conflict can irreversibly harm U.S. security: general nuclear war.

In this regard, if more effective deterrence options are truly desired, it could be worth considering recent proposals to bolster NATO's stocks of conventionally-armed, theater-range ballistic missiles.52 Though not without risk and potential for escalation, an enhanced conventionally-armed missile force would at least reinforce the notion that whatever response NATO takes to potential aggression by Russia in the Baltic region, it definitely should not be of a nuclear nature.

Operational limitations on NATO’s tactical nuclear weapons

For the sake of analytic thoroughness, it is still worth exploring a final conceit of tactical weapons advocates: that they could be decisive, if needed, in compensating for NATO’s conventional weakness in northeast Europe.

To be clear, the balance of forces in the Baltic region does not favor NATO. Although NATO has attempted to buttress Baltic defenses in recent years, most analysts believe Russia could easily invade and take Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania if it chose to do so.53 In part this is because the alliance and the United States have been wary of permanently basing forces in Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, fearing that such a presence would be overly antagonistic towards Russia.54 This complicates the already challenging problem of defending the small, exposed Baltic states that are linked to the rest of alliance territory through the narrow strip of border between Poland and Lithuania, an area known as the Suwalki Gap.

Given these shortcomings, could tactical nuclear weapons provide effective compensation for Russia’s local superiority in conventional forces? The answer is a resounding "no" due to the operational weaknesses of the B61s and additional factors in the Baltic region that would inhibit effective nuclear use.

First, the B61 is a traditional "dumb" bomb reliant on gravity to free-fall out of an aircraft. A plane carrying a B61 must fly over its target and release it in a manner little different from World War II bombers, exposing itself to air defenses. As discussed earlier, the aircraft that would likely convey the B61 under NATO auspices belong to the host countries where the weapons are stored: Belgium, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, and Turkey. The only European aircraft currently certified for the DCA role are the F-16 and the Tornado. These are fourth-generation aircraft without stealth characteristics. There is almost no chance such an aircraft would survive the intense web of air defenses Russia has built up in northeast Europe and deliver its B61 on target.

Admittedly, improvements are planned to NATO capabilities. The Mod 12 version of the B61 will have a new tail-kit to enhance accuracy.55 And three of the DCA nations—Belgium, Italy, and the Netherlands—are in the process of acquiring the stealthy F-35. However, none of this will change the fundamental nature of the B61 as a free-fall bomb. The F-35s will still need to fly into the teeth of Russian air defenses and pass over their intended target to deliver the B61. Even with its stealth characteristics, the F-35's ability to survive and deliver its payload is doubtful. Also, the F-35's certification for the nuclear role is still three years away.56

U.S. planes could also conceivably fly the missions, but currently the only two American fighter aircraft rated to deliver the B61 are the non-stealthy F-15 and the F-16. America also has the F-35, but it would, again, face the same operational limitations in trying to deliver a gravity bomb discussed above. The B-2 bomber is yet another option and might have the best chance of accomplishing the task from a survivability standpoint, but it is generally considered an element of the U.S. strategic nuclear posture. Its use could be misread as the start of a general nuclear war, not just a "tactical" employment.57 Also, if the B-2 was used, it could launch from CONUS, obviating the need for the forward deployment of the B61s in Europe.

Second, there is the complex nature of the "dual-key" arrangements in which the United States authorizes release of the B61 and the host nation sanctions use of its aircraft as a delivery system.58 At the height of the Cold War, these procedures were cumbersome, and that was when they were routinely practiced. One estimate from 1987 suggested it would take 24 hours to process a "top down" request to use tactical nuclear weapons—that is, the senior NATO commander, SACEUR, asking for the requisite authorization. A "bottom up" request—i.e., from a commander in the field—might have taken up to 60 hours.59 (That is the same period of time the RAND wargame estimated it would take Russia to capture two of the three Baltic capitals.) It seems unlikely NATO has expedited the authorization process in the intervening 33 years given that the prospect of employing tactical nuclear weapons has been dormant for so long.

It is also possible a host country might conceivably veto a request to deploy a B61, should the United States approve release of the weapon. Many of the countries which operate DCA aircraft have strong anti-nuclear lobbies. In January 2020, for example, Belgium's parliament narrowly defeated a measure that would have necessitated the withdrawal of the B61s from its soil.60 More recently, leading members of Germany’s Social Democrats—part of Chancellor Angela Merkel's ruling coalition—called for removal of U.S. nuclear weapons from German territory.61 Whether such opposition would translate to hesitation to use nuclear weapons in an actual crisis is uncertain, of course, but it adds yet another variable to NATO’s ability to effectively employ its tactical nuclear weapons in a timely manner.

A word is also needed here about the W76-2. It is true the United States and the United Kingdom each have a submarine-launched tactical nuclear weapon that could be applied to a Baltic contingency if necessary.62 But this presents a final problem: warhead ambiguity. Although the warhead in the American and British arsenals is low-yield and thus technically "tactical," the delivery vehicle—the Trident submarine-launched ballistic missile—is strategic. It is the same delivery system that carries the larger warheads that would be used to conduct a global nuclear war. From the Russian perspective, it is impossible to know the yield of the warhead on the missile that has been launched. Is it the W76-2 with a single 5-kiloton yield or a W88 with a 475-kiloton yield?63 Moreover, does the Russian early warning system have the fidelity to tell the warhead will come down in, say, Latvia as opposed to further east on Russian territory?

If those questions cannot be answered definitively—and it can strongly be argued they cannot—then resort to a submarine-launched low-yield weapon becomes an extraordinarily dangerous crap shoot. Realistically, how can its use be sanctioned if the intent of its employment is opaque and the potential response indeterminate?

A final factor works against effective nuclear use in a Baltic contingency: the absence of viable targets.64 There are three areas where NATO could direct a tactical nuclear strike: on Russian forces once they enter the Baltic states, on Russian forces transiting Belarus, or on Russia itself. The latter option should be categorically ruled out: tactical employment would immediately take on strategic consequences and the possibility for a general nuclear war would loom.

Use on the territory of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania is problematic for obvious reasons. They are not large countries and even limited nuclear employment could have massive humanitarian and environmental consequences. And once Russian forces reach major cities, it truly would be impossible to “save” the Baltic states through nuclear use without killing significant portions of their population. At worst, NATO nuclear use could devolve into a microversion of "Carte Blanche" played out in real life.

That leaves Belarus.65 As already discussed, a significant difference from Cold War targeting options is the absence of Warsaw Pact territory to strike as a means of signaling NATO intent without actually detonating weapons over the Soviet/Russian homeland. Belarus theoretically comes closest to fulfilling the Warsaw Pact's role today, but that is a deeply imperfect analogy.

Although Belarus is often taken for granted as a Russian stooge, the reality is quite different. It is possible Western planners overestimate how much Belarus would overtly cooperate with Russia in a Baltic invasion scenario.66 Indeed, some have suggested Belarus itself might be a potential victim of invasion rather than a willing partner.67 Thus, strikes against Belarus could result in the bombing of a third-party country that is not even a willing participant in the conflict.

In summary, the argument that tactical nuclear weapons could help defend the Baltic states in the face of local Russian conventional superiority unravels quickly. The weapons are unlikely to be effectively delivered, numerous factors work against their timely employment, and, perhaps most importantly, there are no viable targets that would not involve either starting a general nuclear war or destroying the people and territory NATO is intending to defend.

Assessing Russian intentions

In this discussion, it is also worth considering how much of a threat Russia actually is to the Baltic states. The region's historical relationship to Russia is marginal; the Baltic states do not fall into the same category as Ukraine or Crimea, areas many Russians have always considered essential parts of their country. Other than creating a land bridge to the Kaliningrad enclave, there is little apparent strategic value to Russia invading the Baltic states.

Added to this is the fact that Russia under Putin has been a bit like a vampire: it seems to need an invitation to enter. With the notable (and painful) exception of Chechnya, Russia has only deployed its military forces into regions where it could expect a favorable or at least neutral local response. This has been the case in Abkhazia, Crimea, the Donbas, South Ossetia, and even Syria to an extent. While it is certainly possible Russia could invade a more hostile populace, it would come with costs that Russia might not want to pay unless there was a clear strategic advantage.

Sacking the Baltic states does not meet that criteria. There would be a significant price—economic and militarily—to occupying and garrisoning those three states indefinitely, possibly while facing ongoing low-level insurgencies post-invasion. As one retired Russian general staff officer told the writer Mark Galeotti, "The problem with the Baltic states is that they’re full of Balts."68

If it is not actually clear Russia wants to invade Estonia, Latvia, or Lithuania, it seems even less likely that Russia would risk nuclear employment to do so. Tactical nuclear use on Baltic territory would essentially be irradiating and destroying the territory Russia allegedly covets and which most Western analysts believe it could take handily through conventional means.

There are also serious questions about whether Russia would detonate nuclear weapons so close to its own territory. A conflict in Estonia, for example, would take place less than 100 miles from Russia's second city, St. Petersburg. Significantly, one academic assay of views among military planners in Estonia and Latvia found that there was very limited concern over direct Russian nuclear threats or potential use against their territory.69

To be clear, Russia is far from a benign dove. There is no question Russia interferes in the affairs of its neighbors, most prominently in Ukraine. Its seizure of the Crimea in 2014 was patently illegal. Through its ongoing support to the Donbas insurgency, it abets Europe's longest running war, one that has taken at least 14,000 lives.70 Russia has also shown revanchist tendencies in its support for a number of other quasi-ministates on the territory of the former Soviet Union, including Transnistria in Moldova and Abkhazia and South Ossetia in Georgia.

And because Russia might not want to openly invade the Baltic states does not mean it will not seek other means to destabilize or manipulate them. The same Estonian and Latvian military planners who dismissed direct nuclear threats did worry Russia could leverage its nuclear arsenal to deter NATO forces from intervening against hybrid warfare or low-level aggression in the Baltic states.71 But Russia is also something else that is not commonly accepted: weak. Its strategic position has declined significantly over the last thirty years through the collapse of the Soviet Union, via the enlargement of NATO, with the ascendance of American unipolarity, and also through the rise of China. Russia has seen its status and power diminished.

None of this is to excuse Russian actions. But it is to provide context for them. For all the fear Russia engenders, it is easy to forget it operates from a position of deep inferiority vis-à-vis NATO and the United States. The alliance's position has improved markedly from the Cold War. Where once it had to defend from a central front located east of Berlin, Russian forces are now located almost 1,000 miles further away from the heart of NATO territory. The alliance has added the territory of East Germany and Poland to its strategic depth, as well as the buffer created by independent states in Belarus and Ukraine. A Russian invasion would have to traverse at least two large countries before coming close to the old border of NATO.

Meanwhile, Moscow has lost the territory and forces of the Warsaw Pact and major portions of the Soviet Union. After decades of decay and decline it has begun to rebuild its armed forces into a capable regional force. But it is no longer the global power the Soviet Union was and has no reasonable prospect of again being so.

To call Russia a "near-peer competitor" on the same scale as China is generous. In truth, Russia is a middling power with an economy that does not even crack the top ten for GDP, coming in eleventh—right behind Canada.72 Moreover, it has unwisely chosen to expend its limited economic resources on ill-advised neo-imperial projects, such as its open-ended military adventure in Syria and support to the various "quasi-states" cited above. This is one reason Russia has largely invested in modest modernization instead of next-generation capabilities when it comes to its military.73 To cite the most salient example, despite having developed an impressive capability in the T-14 Armata tank, Russia is deferring mass production, opting instead to invest in an upgraded version of the T-72, a standard from the Cold War.74

With this as background, Russia's military doctrine reads quite differently. Instead of an aggressive warning that Russia will use nuclear weapons widely and openly to achieve its ends, the doctrine instead illustrates Russia is a lesser power dealing with what it views as superior threats. This should, incidentally, include not only NATO and the United States, but also China. For all the concern over Russian-Chinese fraternity against American power, it should not be forgotten Moscow still eyes its eastern neighbor with long-term concern.

Russia's nuclear posture thus appears designed to deter aggression, not one that openly advocates for unlimited nuclear use as a substitute for conventional war. Russia, in short, views tactical weapons much in the same way NATO did when it believed it faced a much superior conventional Soviet threat.

The altered equation of nuclear burden-sharing

To summarize, in looking at tactical nuclear weapons in a Baltic contingency, the threat is uncertain, the cause does not merit nuclear use, and the weapons are not applicable. So why modernize them? Why keep them at all given their potential to turn a regional crisis into something far more dangerous?

The only possible answer is the traditional role the weapons are said to play in nuclear burden-sharing between the European allies and the United States. This recently became an issue again, following the aforementioned call by some German Social Democrats to withdraw the B61s from German territory. In response, two foreign policy advisers to former Vice President Biden penned an essay in Der Spiegel reminding the German public of the dual nature of NATO's nuclear commitment.75 On the one hand, the United States pledges to defend member states from nuclear attack with the attendant danger to its own population and territory—to risk "Chicago for Lyon" as De Gaulle put it. On the other, the European allies participate in NATO nuclear operations—including hosting weapons and maintaining DCA aircraft—to share the burden (and risk) of nuclear employment should it be needed.

Deployed and reserve U.S. nuclear forces by type

The problem though, as discussed in this paper, is that NATO's tactical nuclear weapons have no functional value at this point. It is essentially a debate over a gun that cannot shoot. How does German maintenance of delivery systems for weapons that cannot be used (never mind should not be used) somehow bolster its relationship with America in the twenty-first century?

This is a point often missed by alliance advocates on both sides of the Atlantic. Whereas once nuclear burden-sharing may, in fact, have strengthened alliance cohesion, in the current environment, the prospect of nuclear use is likely to drive the United States away in the long run, rather than keep it anchored in Europe.76

While it can be debated in retrospect, during the Cold War, the stakes were seen as sufficiently high that nuclear risks were worth incurring. Each side perceived its own system as being incompatible with the other's—capitalism and communism could not coexist. Any open conflict between the two would thus rapidly take on a zero-sum nature. The stakes of a NATO-Warsaw Pact war therefore were no less than each side’s way of life.

Under those circumstances resort to nuclear weapons made sense (if such a phrase can be used) given the enormous consequences of defeat. Operations and arrangements that enhanced European participation in nuclear planning and delivery bolstered Alliance cohesion under those unique circumstances.

That is simply not the case now. There is no existential struggle between NATO and Russia, and it is wrong to base nuclear planning—to include burden-sharing—on an outdated assumption.

President Trump's administration has undoubtedly placed renewed strains on the alliance. But his policies are less the source of that stress than a symptom of long-growing concerns across the American political spectrum over NATO's value.77 At the core of these doubts are the potential for NATO to ensnare the United States in a nuclear war it otherwise would not fight.78

Unless NATO can find a way to conduct its defensive mandate more effectively through conventional means, pressure will grow to reexamine the maintenance of strong Transatlantic links in America. Burden-sharing has been turned on its head: the nuclear mission is far more likely to end NATO than preserve it.

From Europe's perspective, the money expended on nuclear burden-sharing could be better applied to conventional force investments and infrastructure improvements that allow NATO to better deter without recourse to nuclear weapons. That Germany has signaled its intent to buy a less capable aircraft (the F-18) specifically to meet the DCA mission—instead of purchasing a more advanced platform better suited to modern warfighting—embodies how skewed NATO nuclear thinking has become.79

Dialogue should be the imperative

There is only one purpose the B61s in Europe can now serve: as a gesture, through their removal, to restart a constructive dialogue with Russia on reducing risks—including nuclear threats—in Europe. Talking to Russia would not reward its bad behavior, it simply would be recognizing diplomatic discussions are useful in and of themselves for promoting stability and resolving conflict—even with states we dislike. It is again worth emphasizing NATO and the United States routinely held talks with a far more dangerous and insidious state—the Soviet Union—at various points during the Cold War.

Moreover, there are ample subjects for such a dialogue now, from the near misses between NATO and Russian air and naval forces (which occur all too regularly) to major questions surrounding security and stability in Ukraine. The Donbas insurgency and Russia’s annexation of Crimea will not be resolved through NATO's military might. They can only be addressed through diplomatic discussion.

Such talks would no doubt be challenging. Past efforts to "reset" the U.S.-Russia relationship largely foundered, in part because the ambition was to fundamentally change Russian behavior or somehow turn Moscow to Washington's side.80 That is unlikely to happen. Russia is an illiberal, authoritarian regime. Major differences between it and NATO's core states will remain.

But that does not mean there cannot be compromise or that differences cannot be addressed in a manner promoting stability instead of promulgating dangerous nuclear policies from the past. More modest ambitions can succeed, as attested to by various limited U.S.-Russia ventures, such as the Cooperative Threat Reduction program and New START, agreed to in 2010. The simple act of talking can have long-term benefits in trust-building, as examples from the Cold War, such as the MBFR dialogue, illustrate.

There will, of course, be those who argue that the B61s should not be unilaterally withdrawn without reciprocal concessions by Russia, such as reduction of its own tactical weapons stock. But this misses two points: first, Russia's tactical nuclear weapons are likely a fixed variable so long as Russia operates from a position of weakness vis-à-vis NATO, a situation which will not change in the foreseeable future. Second, withdrawing the B61s can be useful precisely because it is nonreciprocal—an unambiguous gesture to reduce tension that costs NATO nothing in terms of operational capability.

Withdrawal of the B61s would be a bold move, but a minor one compared to the risk President Bush incurred when unilaterally reversing decades of tactical nuclear deployment in September of 1991—also without hard assurances the Soviets would reciprocate. Yet that step helped lay the groundwork for a decade of cooperation with Moscow on nuclear reductions.

Neither Oppenheimer's "two scorpions" nor Kissinger's "mutual suicide" analogy should obtain today. Russia and the United States have important differences and there are legitimate defense planning concerns for NATO in the Baltic region. But neither of these should rise to the level of nuclear war. The days of the zero-sum, existential competition are over. So, too, should be the nuclear policies and strategies that era begat.

The B61s are anachronisms. It is long past time they were removed.

Endnotes

1 There are multiple ways to attempt to clarify what constitutes a “tactical nuke,” but none is wholly satisfying. The most common delineations relate to their yield (low), range of their delivery systems (short), or even their purpose (usually some form of battlefield employment). But these criteria quickly break down when applied to the real world. If the low-yield W76-2 warhead were launched into a Russian city, the effects would be decidedly strategic. Likewise, “battlefield employment” of a tactical nuclear weapon against, say, an airfield on Russian territory, could have unwanted strategic implications. Even range is not an entirely fixed criteria as, in theory, NATO’s B61 bombs could be carried deep into Russian territory if the delivery aircraft were refueled en route. For the purposes of this paper, “tactical nuclear weapons” is meant to mean, from the U.S. side, the B61 air-delivered bomb and the W76-2 submarine launched low-yield warhead; the estimated 1,000 to 2,000 active Russian nuclear warheads not governed by extant arms control agreements, such as New START; and U.S. and Soviet battlefield weapons deployed during the Cold War and eventually withdrawn under the Presidential Nuclear Initiatives. For an extended discussion of the difficulty in defining “tactical nuclear weapons,” see U.S. Library of Congress, Congressional Research Service, Nonstrategic Nuclear Weapons, R32572 (2019), 7-10, and Paul Schulte, “Tactical Nuclear Weapons in NATO and Beyond: A Historical and Thematic Examination,” in Tactical Nuclear Weapons and NATO, ed. Tom Nichols, Douglas Stuart, and Jeffrey D. McCausland (Carlisle, PA: Strategic Studies Institute, 2012), 13–15, https://www.hsdl.org/?view&did=706112.

2 J. Robert Oppenheimer, “Atomic Weapons and American Policy,” Foreign Affairs, 31, no. 4 (July 1953): 529, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/1953-07-01/atomic-weapons-and-american-policy.

3 See Office of the Secretary of Defense, Nuclear Posture Review, February 2018, 30–31, 52–55, https://media.defense.gov/2018/Feb/02/2001872886/-1/-1/1/2018-NUCLEAR-POSTURE-REVIEW-FINAL-REPORT.PDF.

4 See, for example, Elbridge Colby, “If You Want Peace, Prepare for Nuclear War,” Foreign Affairs, 97, no. 6 (November/December 2018): 25–32, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/china/2018-10-15/if-you-want-peace-prepare-nuclear-war.

5 Schulte, “Tactical Nuclear Weapons in NATO and Beyond: A Historical and Thematic Examination,” 19–20.

6 Schulte, “Tactical Nuclear Weapons in NATO and Beyond: A Historical and Thematic Examination,” 21.

7 Schulte, “Tactical Nuclear Weapons in NATO and Beyond: A Historical and Thematic Examination,” 24.

8 Dale Herspring, The Soviet High Command 1967–1989: Personalities and Politics (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1990), 34.

9 Herspring, The Soviet High Command 1967–1989: Personalities and Politics, 37.

10 J. Michael Legge, Theater Nuclear Weapons and the Strategy of Flexible Response (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 1983): 6–7, https://www.rand.org/pubs/reports/R2964.html.

11 Matthias Uhl, “Storming onto Paris,” in War Plans and Alliances in the Cold War: Threat Perceptions in the East and West, eds. Vojtech Mastny, Sven Holtsmark, and Andreas Wenger (Zurich: Center for Security Studies, 2006), 65, as quoted in Schulte, “Tactical Nuclear Weapons in NATO and Beyond: A Historical and Thematic Examination,” 33–34.

12 Herspring, The Soviet High Command 1967–1989: Personalities and Politics, 83–84.

13 Herspring, The Soviet High Command 1967–1989: Personalities and Politics, 174–176.

14 On the influence of Maxwell Taylor’s The Uncertain Trumpet, see Peter F. Wittereid, “A Strategy of Flexible Response,” Parameters, 2, no. 1, 1972, 2–16.

15 For an excellent discussion of this policy’s development and implications, see Legge, Theater Nuclear Weapons and the Strategy of Flexible Response.

16 Catherine McArdle Kelleher, “NATO Nuclear Operations,” in Managing Nuclear Operations, ed. Ashton B. Carter, John D. Steinbruner, and Charles A. Zraket (Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution, 1987), 447, and Hans S. Kristensen and Matt Korda, “United States Nuclear Forces, 2019,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 75, no. 5 (August 30, 2019): 252.

17 For a good overview of the PNIs from the U.S. side, see Susan J. Koch, The Presidential Nuclear Initiatives of 1991–1992, Center for the Study of Weapons of Mass Destruction Case Study 5 (Washington, DC: National Defense University Press, 2012), https://ndupress.ndu.edu/Portals/68/Documents/casestudies/CSWMD_CaseStudy-5.pdf.

18 One informed observer cites Presidential Decision Directive 74, signed by President Bill Clinton in November 2000, as fixing the B61 force level in Europe at 480 bombs, over three times the current stockpile. See the discussion in Hans S. Kristensen, U.S. Nuclear Weapons in Europe a Review of Post-Cold War Policy, Force Levels, and War Planning (New York, NY: Natural Resources Defense Council, 2005): 8–17.

19 Hans S. Kristensen and Matt Korda, “United States Nuclear Forces, 2019,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 75, no. 3 (April 29, 2019): 124, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00963402.2019.1606503.

20 David A. Shlapak and Michael W. Johnson, Reinforcing Deterrence on NATO’s Eastern Flank (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2016): 1, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR1253.html.

21 Loren B. Thompson, “Why the Baltic States Are Where Nuclear War Is Most Likely to Begin,” National Interest, July 20, 2016, https://nationalinterest.org/blog/the-buzz/why-the-baltic-states-are-where-nuclear-war-most-likely-17044.

22 See, for example, Nikolai Sokov, “Why Russia Calls a Limited Nuclear Strike ‘De-escalation,’“ Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, March 13, 2014, https://thebulletin.org/2014/03/why-russia-calls-a-limited-nuclear-strike-de-escalation/#; Matthew Kroenig, “The Renewed Russian Nuclear Threat and NATO Nuclear Deterrence Posture,” Atlantic Council, February 3, 2016, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/issue-brief/russian-nuclear-threat/; and Elbridge Colby, “Russia’s Evolving Nuclear Doctrine and its Implications,” Fondation pour la Reserche Stratigique, January 12, 2016, https://www.frstrategie.org/en/publications/notes/russias-evolving-nuclear-doctrine-implications-2016.

23 Several factors make Russia’s compliance with its PNI commitments difficult to track. First, there was the sheer scale of its tactical nuclear holdings at the Cold War’s end—perhaps in excess of 20,000 weapons—not all of which were on Russian territory. The second was Russia’s dire financial situation in the 1990s and early 2000s, which limited the funds available for dismantlement of the weapons. Added to this was a lack of transparency on Russia’s part throughout the process. That said, it is believed Russia has dismantled a significant portion of its Cold War arsenal while other systems are no longer operational due to obsolescence. See the discussion in Library of Congress, Nonstrategic Nuclear Weapons, 26–28.

24 The figures of 1,000, 1,830, and 2,000 are cited, respectively, by analyses from the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI), the Federation of Atomic Scientists (FAS), and the Department of Defense (DoD). See Igor Sutyagin, Atomic Accounting: A New Estimate of Russia’s Non-strategic Nuclear Forces (London: Royal United Services Institute, 2012), 3, https://rusi.org/sites/default/files/201211_op_atomic_accounting.pdf; Hans S. Kristensen and Matt Korda, “Russian Forces, 2019,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 75, no. 2 (March 4, 2019): 80, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/00963402.2019.1580891?needAccess=true; and Office of the Secretary of Defense, Nuclear Posture Review, 58.

25 Serge Schmemann, “Russia Drops Pledge of No First Use of Atom Arms,” New York Times, November 4, 1993, https://www.nytimes.com/1993/11/04/world/russia-drops-pledge-of-no-first-use-of-atom-arms.html.

26 Part of the challenge in interpreting the precise meaning of Russia’s military doctrine as it relates to nuclear use is that opinions and writings on the subject are as wide and varied within the Russian defense establishment as similar subjects can be among U.S. strategic thinkers. The Center for Naval Analyses has conducted a meta-study of Russian writings on escalation, which provides important insight on the texture of the debate within Russia itself. See Anya Fink and Michael Kofman, with Kasey Stricklin and Mary Chesnut, Russian Strategy for Escalation Management: Key Debates and Players in Military Thought (Alexandria, VA: Center for Naval Analyses, April 2020), https://www.cna.org/CNA_files/PDF/DRM-2019-U-022455-1Rev.pdf.

27 U.S. Library of Congress, Nonstrategic Nuclear Weapons, 25, and Paul K. Davis, J. Michael Gilmore, David R. Frelinger, Edward Geist, Christopher K. Gilmore, Jenny Oberholtzer, and Danielle C. Taraff, Exploring the Role Nuclear Weapons Could Play in Deterring Russian Threats to the Baltic States, Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2019, 33–34, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR2781.html.

28 For a good discussion of doubts surrounding “escalate to de-escalate,” see Davis et al., Exploring the Role Nuclear Weapons Could Play in Deterring Russian Threats to the Baltic States, 33-35, and Olga Oliker, “Russia’s Nuclear Doctrine: What We Know, What We Don’t, and What That Means,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, May 5, 2016, https://www.csis.org/analysis/russia’s-nuclear-doctrine.

29 U.S. Library of Congress, Nonstrategic Nuclear Weapons, 24.

30 “Military Doctrine of the Russian Federation: Approved by the Order of the President of the Russian Federation, on April 21, 2000, Order No. 706,” as quoted in Oliker, “Russia’s Nuclear Doctrine,” 3.

31 Oliker, “Russia’s Nuclear Doctrine,” 2–3, and U.S. Library of Congress, Nonstrategic Nuclear Weapons, 23–24.

32 The release in June 2020 of Russia’s state policy of nuclear deterrence provided little additional clarity on Russia’s nuclear intentions beyond what was already known from examination of the various iterations of its military doctrine over the years. See “On Basic Principles of State Policy of the Russian Federation on Nuclear Deterrence,” Executive Order of the President of the Russian Federation, June 8, 2020, English translation via The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation, https://www.mid.ru/en/web/guest/foreign_policy/international_safety/disarmament/-/asset_publisher/rp0fiUBmANaH/content/id/4152094.

33 Office of the Secretary of Defense, Nuclear Posture Review, 8, 30–31.

34 Office of the Secretary of Defense, Nuclear Posture Review, 52–55.

35 “Testimony Statement of The Honorable Lisa E. Gordon-Hagerty, Under Secretary for Nuclear Security and Administrator of the National Nuclear Security Administration, U.S. Department of Energy, before the Subcommittee on Strategic Forces, Senate Committee on Armed Services,” Senate Armed Services Committee, May 8, 2019, 4, https://www.armed-services.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Gordon-Hagerty_05-08-19.pdf.

36 John Rood, “Statement on the Fielding of the W76-2 Low-Yield Submarine Launched Ballistic Missile Warhead,” U.S. Department of Defense, February 4, 2020, https://www.defense.gov/Newsroom/Releases/Release/Article/2073532/statement-on-the-fielding-of-the-w76-2-low-yield-submarine-launched-ballistic-m/.

37 Office of the Secretary of Defense, Nuclear Posture Review, 54.

38 Office of the Secretary of Defense, Nuclear Posture Review, ix–x, 8–9, 30–31.

39 See comments by Greg Weaver, Deputy Director for Strategic Stability, The Joint Staff (J-5), starting approximately at the 1:35 mark in “Nuclear Posture Review,” C-SPAN, February 18, 2018, https://www.c-span.org/video/?441268-1/policy-forum-focuses-trump-administrations-nuclear-policy.

40 See, for example, comments by then-Secretary of Defense James N. Mattis in Aaron Mehta, “Mattis: No Such Thing as a ‘Tactical’ Nuclear Weapon,” Defense News, February 6, 2018, https://www.defensenews.com/space/2018/02/06/mattis-no-such-thing-as-a-tactical-nuclear-weapon-but-new-cruise-missile-needed/.

41 Office of the Secretary of Defense, Nuclear Posture Review, 58.

42 Davis et al., Exploring the Role Nuclear Weapons Could Play in Deterring Russian Threats to the Baltic States.

43 Davis et al., Exploring the Role Nuclear Weapons Could Play in Deterring Russian Threats to the Baltic States, 79.

44 Davis et al., Exploring the Role Nuclear Weapons Could Play in Deterring Russian Threats to the Baltic States, 78–79.

45 Davis et al., Exploring the Role Nuclear Weapons Could Play in Deterring Russian Threats to the Baltic States, 78.

46 Davis et al., Exploring the Role Nuclear Weapons Could Play in Deterring Russian Threats to the Baltic States, xi, 40.

47 Paul Lewis, “U.S. Pledge to NATO To Use Nuclear Arms Criticized by Kissinger,” New York Times, September 2, 1979, https://www.nytimes.com/1979/09/02/archives/us-pledge-to-nato-to-use-nuclear-arms-criticized-by-kissinger-past.html.

48 Joshua Shifrinson, “Time to Consolidate NATO?” Washington Quarterly, 40, no. 1 (Spring 2017): 109–123.

49 Ronald D. Asmus, Richard L. Kugler, and F. Stephen Larrabee, “Building a New NATO,” Foreign Affairs, 72, no. 4 (September/October 1993): 28–40, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/southeastern-europe/1993-09-01/building-new-nato.

50 Though assimilation has been imperfect at times, by and large, Russian speakers in the Baltics perceive their economic prospects as far better in the Baltic states than in Russia. They also have mainstream political parties which represent their interests. In general, good governance has helped the Baltic states inoculate themselves from Russian information operations. See, for example, Kristian Nielsen and Heiko Paabo, “How Russian Soft Power Fails in Estonia: Or, Why the Russophone Minorities Remain Quiescent,” Journal of Baltic Security, 1, no. 2 (2015): 125–57, https://content.sciendo.com/view/journals/jobs/1/2/article-p125.xml.

51 “Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2011-2018),” North Atlantic Treaty Organization, March 14, 2019, https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/pdf_2019_03/190314-pr2018-34-eng.pdf.

52 Luis Simon and Alexander Lanoszka, “The Post-INF European Missile Balance: Thinking About NATO’s Deterrence Strategy,” Texas National Security Review, 3, no. 3 (Summer 2020), https://tnsr.org/2020/05/the-post-inf-european-missile-balance-thinking-about-natos-deterrence-strategy/.

53 Steven Maguire, “The Positive Impact of NATO’s Enhanced Forward Presence,” Strategy Bridge, September 3, 2019, https://thestrategybridge.org/the-bridge/2019/9/3/the-positive-impact-of-natos-enhanced-forward-presence.

54 Instead, NATO has tried to bolster Baltic defenses through the rotational presence of Enhanced Forward Presence (EFP) battlegroups deployed in Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland. The initiative grew out of the 2016 Warsaw Summit and came in response to Russian actions in Ukraine two years earlier. The battlegroups themselves number from roughly 1,000 to 1,400 troops and are each led by a “traditional” ally, with Canada leading the Latvian deployment, the United Kingdom taking the lead in Estonia, Germany heading up the Lithuania mission, and the United States assuming responsibility for Poland. See “NATO’s Enhanced Forward Presence,” North Atlantic Treaty Organization, March 2019, https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/pdf_2019_04/20190402_1904-factsheet_efp_en.pdf.

55 Hans M. Kristensen, “General Confirms Enhanced Targeting Capabilities of B61-12 Nuclear Bomb,” Federation of Atomic Scientists, January 23, 2014, https://fas.org/blogs/security/2014/01/b61capability/.

56 January 2023 is currently the expected date for the F-35’s certification in the nuclear role. U.S. Library of Congress, Congressional Research Service, F-35 Joint Strike Fighter (JSF), RL30563 (2020), 22, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/weapons/RL30563.pdf.

57 Davis et al., Exploring the Role Nuclear Weapons Could Play in Deterring Russian Threats to the Baltic States, 52–53.

58 For an extended discussion of the complicated sequence of events necessary for NATO to execute a nuclear strike, see Karl-Heinz Kamp and Robertus C.N. Remkes, “Options for NATO Nuclear Sharing Arrangements,” in Reducing Nuclear Risks in Europe: A Framework for Action, ed. Steve Andreasen and Isabelle Williams, (Washington, DC: Nuclear Threat Initiative, 2011), 81–82.

59 Kelleher, “NATO Nuclear Operations,” 457.

60 Alexandra Brzozowski, “Belgium Debates Phase-out of U.S. Nuclear Weapons on Its Soil,” Euroactiv, January 17, 2020, https://www.euractiv.com/section/defence-and-security/news/belgium-debates-phase-out-of-us-nuclear-weapons-on-its-soil/.

61 Matthew Karnitschnig, “German Social Democrats Tell Trump to Take U.S. Nukes Home,” Politico, May 3, 2020, https://www.politico.eu/article/german-social-democrats-tell-donald-trump-to-take-us-nukes-nuclear-weapons-home/.

62 Public information on the United Kingdom’s submarine-launched tactical nuclear weapon is scarce, but its existence is generally acknowledged and pre-dates the U.S. W76-2 by more than a decade. See Michael Quinlan, Thinking About Nuclear Weapons: Principles, Problems, Prospects, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 127.

63 RAND’s Austin Long argues that the Russians would be able to discern a Trident carrying a W76-2 from a W88 or W76 (strategic warheads) because the latter are thought to be loaded in multiples aboard each SLBM. That is, if the Russians saw five warheads separate from a single Trident, they would know they were strategic warheads, while a single warhead would mean a tactical weapon. But there is nothing, from the Russian standpoint, to guarantee that a single W88 or W76 could not be on the missile. Depending on Russia to correctly “read the tea leaves” and accurately guess the nature of the warhead in question seems to be asking a lot under extreme crisis conditions with a great deal at stake. See Austin Long, “Discrimination Details Matter: Clarifying an Argument about Low-Yield Nuclear Warheads,” War on the Rocks, February 16, 2018, https://warontherocks.com/2018/02/discrimination-details-matter-clarifying-argument-low-yield-nuclear-warheads/.

64 A 2016 tabletop exercise conducted by the Center for American Progress also identified the lack of viable targets to be a major concern in a Baltic contingency in which NATO might need to resort to nuclear weapons. The game featured participation by twelve officials from former administrations with experience in the Departments of Defense and State and the national labs. See Adam Mount, “The Case Against New Nuclear Weapons,” Center for American Progress, May 2017, 21–31, https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/security/reports/2017/05/04/431833/case-new-nuclear-weapons/.

65 Russian forces would not necessarily need to transit Belarus, although it would be expedient if Lithuania were an objective, as well as Estonia and Latvia. More importantly, though, Russia would likely want to seal the so-called Suwalki Gap—the thin corridor along the Lithuanian-Polish border through which NATO reinforcements would flow—under most circumstances involving a move against any of the Baltic states. Doing so would require transiting Belarus.

66 Alexander Lanoszka, “The Belarus Factor in European Security,” Parameters 47, no. 4 (2017): 75–84.

67 Jeffrey Mankoff, “Will Belarus Be the Next Ukraine?” Foreign Affairs, February 5, 2020, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/belarus/2020-02-05/will-belarus-be-next-ukraine.

68 Mark Galeotti, “The Baltic States as Targets and Levers: The Role of the Region in Russian Strategy,” George C. Marshall Center for European Security Studies, April 2019, https://www.marshallcenter.org/mcpublicweb/mcdocs/security_insights_28_-_galeotti_-_rsi_-_march_2019_-_letter_size_-_aug_26.pdf.

69 Viljar Veebel, “(Un)justified Expectations on Nuclear Deterrence of Non-nuclear NATO Members: The Case of Estonia and Latvia?” Defense and Security Analysis 34, no. 3, August 2018, 12, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/326742485_Unjustified_expectations_on_nuclear_deterrence_of_non-nuclear_NATO_members_the_case_of_Estonia_and_Latvia.

70 Davis et al., Exploring the Role Nuclear Weapons Could Play in Deterring Russian Threats to the Baltic States, 52–53.

71 Veebel, “(Un)justified Expectations on Nuclear Deterrence of Non-nuclear NATO Members,” 12.

72 Russia’s GDP was 1.66 trillion in 2018, the most recent year compiled by the World Bank. “Gross Domestic Product 2018,” World Bank, December 23, 2019, https://databank.worldbank.org/data/download/GDP.pdf.

73 Richard Connolly and Mathieu Boulegue, “Russia’s Military: More Bark Than Bite,” National Interest, May 23, 2018, https://nationalinterest.org/feature/russias-military-more-bark-bite-25941.

74 Pavel Felgenhauer, “The Pros and Cons of a Russian Push into the Baltics. As Seen from Moscow,” in Security of the Baltic Region Revisited amid the Baltic Centenary, ed. Andris Spruds and Maris Andzans (Riga: Latvian Institute of International Affairs, 2018), 166, https://www.baltdefcol.org/files/files/publications/RigaConferencePapers2018.pdf.

75 Michèle Flournoy and Jim Townsend, “Striking at the Heart of the Trans-Atlantic Bargain,” Spiegel International, June 3, 2020, https://www.spiegel.de/international/world/biden-advisers-on-nuclear-sharing-striking-at-the-heart-of-the-trans-atlantic-bargain-a-e6d96a48-68ef-49ab-8a0c-8a979abf2bb4.

76 For more on this concept, see Mike Sweeney, “What Is NATO Good For?” Strategy Bridge, January 6, 2020, https://thestrategybridge.org/the-bridge/2020/1/6/what-is-nato-good-for.

77 Consider the range of op-eds and think pieces written in the lead up to NATO’s 70th anniversary questioning the alliance’s ongoing utility. See, for example, Barry R. Posen, “Trump Aside, What’s the U.S. Role in NATO?” New York Times, March 10, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/10/opinion/trump-aside-whats-the-us-role-in-nato.html; Walter Russell Mead, “NATO Is Dying, but Don’t Blame Trump,” Wall Street Journal, March 25, 2019, https://www.wsj.com/articles/nato-is-dying-but-dont-blame-trump-11553555665; Douglas Macgregor, “NATO Is Not Dying. It’s a Zombie,” National Interest, March 31, 2019, https://nationalinterest.org/feature/nato-not-dying-it%E2%80%99s-zombie-49747; William Ruger, “NATO at 70: Will Continued Expansion Endanger Americans?” War on the Rocks, April 4, 2019, https://warontherocks.com/2019/04/nato-at-70-will-continued-expansion-endanger-americans/; and Gil Barndollar, “NATO Is 70 and Past Retirement Age,” National Interest, April 8, 2019, https://nationalinterest.org/feature/nato-70-and-past-retirement-age-51482.

78 See the discussion in Shifrinson, “Time to Consolidate NATO?” 110–112.

79 Justin Bronk, “The German Decision to Split Tornado Replacement Is a Poor One,” RUSI Defence Systems, March 26, 2020, https://rusi.org/publication/rusi-defence-systems/german-decision-split-tornado-replacement-poor-one#.Xn6LcmQBhx4.twitterI.

80 Thomas Graham, “Let Russia Be Russia: The Case for a More Pragmatic Approach to Moscow,” Foreign Affairs, October 15, 2019, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/russia-fsu/2019-10-15/let-russia-be-russia.