Key points

ISIS’s caliphate—a radical Sunni protostate—enabled it to recruit jihadists globally, collect taxes to fund terror, and train militants to carry out attacks. Liberating ISIS-held territory was an achievable military mission that enhanced U.S. security.

With the loss of its caliphate, the anti-ISIS mission should have ended. ISIS now consists of scattered groups of fighters, lacks a coherent organization, and has lost its aura of success. It is surrounded by local state and non-state actors opposed to its existence and no longer directly threatens the U.S.

ISIS’s remnants do not justify keeping an indefinite U.S. ground presence. If ISIS manages to reconstitute itself and local forces fail to contain it, U.S. forces could always return with congressional authorization.

Staying to conduct local policing operations is a misuse of the military that risks broader conflict with Iran, Iran-backed Shia militias, Russia, Syria, and others. These dangers make the need to withdraw more urgent.

ISIS’s caliphate is destroyed—end the U.S. military mission

The killing of Iranian IRGC Gen. Qassem Soleimani should mark the beginning of the end of the U.S. counter-ISIS campaign in Iraq and Syria. Though it remains unclear whether Baghdad will legally evict U.S. forces from Iraq, it is likely the continued presence of U.S. forces will, at a minimum, become far more fraught in the midst of escalating tensions with Iran and Shia militias in Iraq. Iranian forces, led by Soleimani, and Iran’s many proxy forces played a key role in defeating ISIS in both Iraq and Syria. Soleimani’s death, ironically, should mark the end of the U.S. military mission in both countries.

The U.S. should re-examine its priorities and strategy in Iraq and Syria. That assessment should acknowledge the decrease in ISIS’s power, capabilities, and potential. U.S. forces are not needed to take on ISIS’s remnants—there is no good reason to run the risks of continued deployment.

The physical caliphate of the Islamic State (ISIS) has been destroyed by the forces of the U.S.-led coalition, in which the U.S. provided most airpower and advising while allied forces carried the ground fight. ISIS, the latest and most dangerous incarnation of Sunni jihadism, has been shattered. The U.S. accomplished its military mission. ISIS’s remnants may regenerate themselves to some degree as an insurgency, but history suggests insurgencies can only suffer permanent defeat at the hands of the governments they have rebelled against. Third-party, expeditionary counterinsurgency (COIN) is only rarely successful, as Americans have been repeatedly learning for the better part of the last two decades.

What made ISIS uniquely threatening was its physical caliphate, a protostate of up to 12 million inhabitants. This caliphate, which would have helped it organize and mount terrorist attacks against the West, is gone.

ISIS has lost most of its fighters and its treasury, as well as most of its intangible power to inspire jihadist recruits and lone wolf attacks. ISIS’s remnants can launch local attacks, but these are primarily squad-sized ambushes and assassinations. At the moment, ISIS is not a serious threat to the states of Iraq and Syria, let alone the U.S. ISIS’s infamy should not distract us from the core questions of capability and national interest: if ISIS is not a credible threat to the U.S., it does not justify the attention of U.S. ground troops, especially in a volatile region where those troops are vulnerable to other threats.

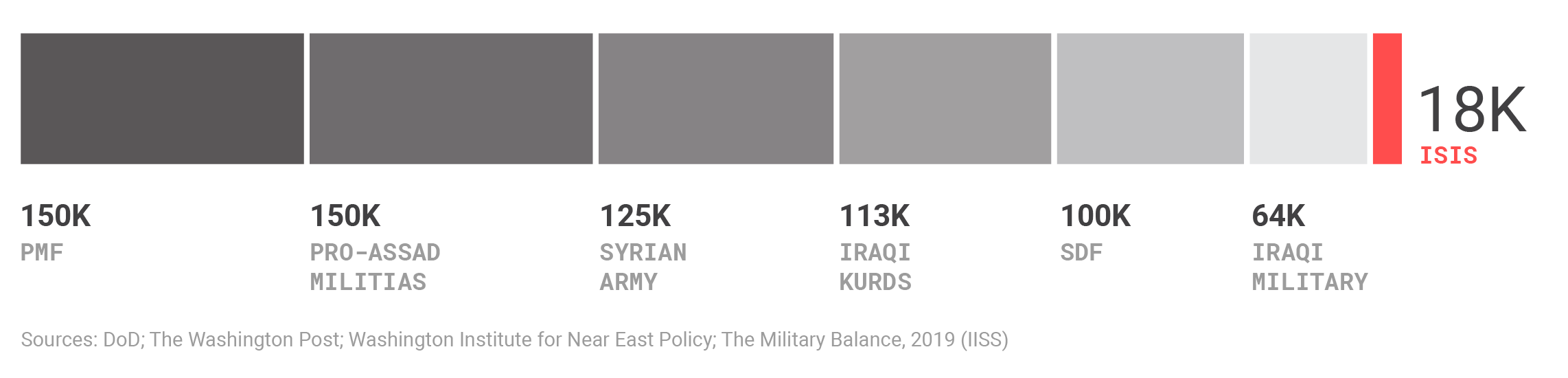

All major regional actors oppose ISIS. Syria, Iraq, Turkey, and Iran can employ far more combat power against an ISIS resurgence than the remaining U.S. forces in Syria can. Syria’s Kurds, after all, were the most significant and successful combat force employed against ISIS—and they themselves were easily routed by the Turkish Army last year.

U.S. withdrawal would force these local forces to take the lead in dealing with ISIS. All of them have a far stronger vested interest in crushing ISIS remnants than the U.S. does. If necessary, U.S. forces could project power to take out any anti-U.S. threats that emerge unchecked by local powers.

The successful campaign to liberate ISIS-held territory

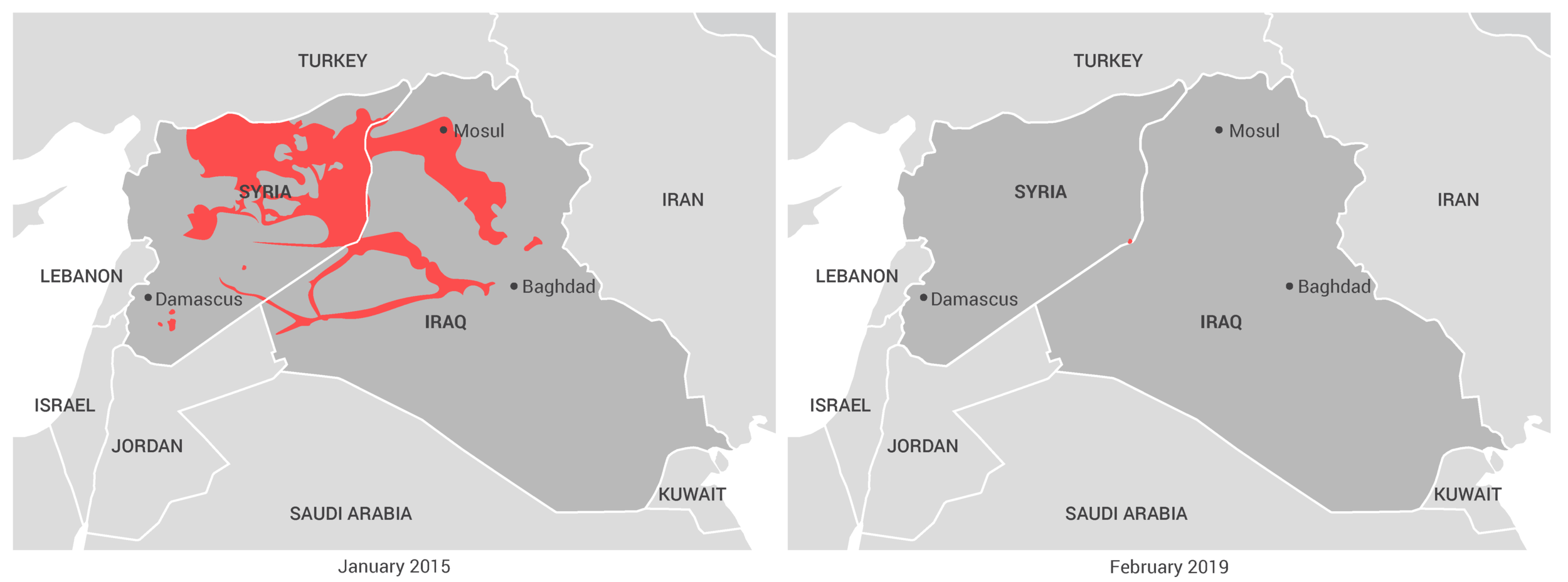

The last remnants of the physical caliphate of ISIS were destroyed when the U.S.-backed Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) declared victory after the Battle of Baghuz Fawqani in March 2019. After peaking in 2015 with control of an embryonic state the size of Great Britain, ISIS has been decimated. It now lacks central organization and physical territory. Losing the caliphate was a massive blow to its prestige, which costs it recruits and discourages jihadists elsewhere from claiming adherence to it. Losing territory meant losing organizational capacity to train and plan anti-Western terrorist attacks.

The conquest of ISIS’s caliphate, and the recent killing of the group’s founding leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, are real victories that should be acknowledged by concluding the missions that achieved them. The rationale for military intervention in Iraq and Syria has ended.

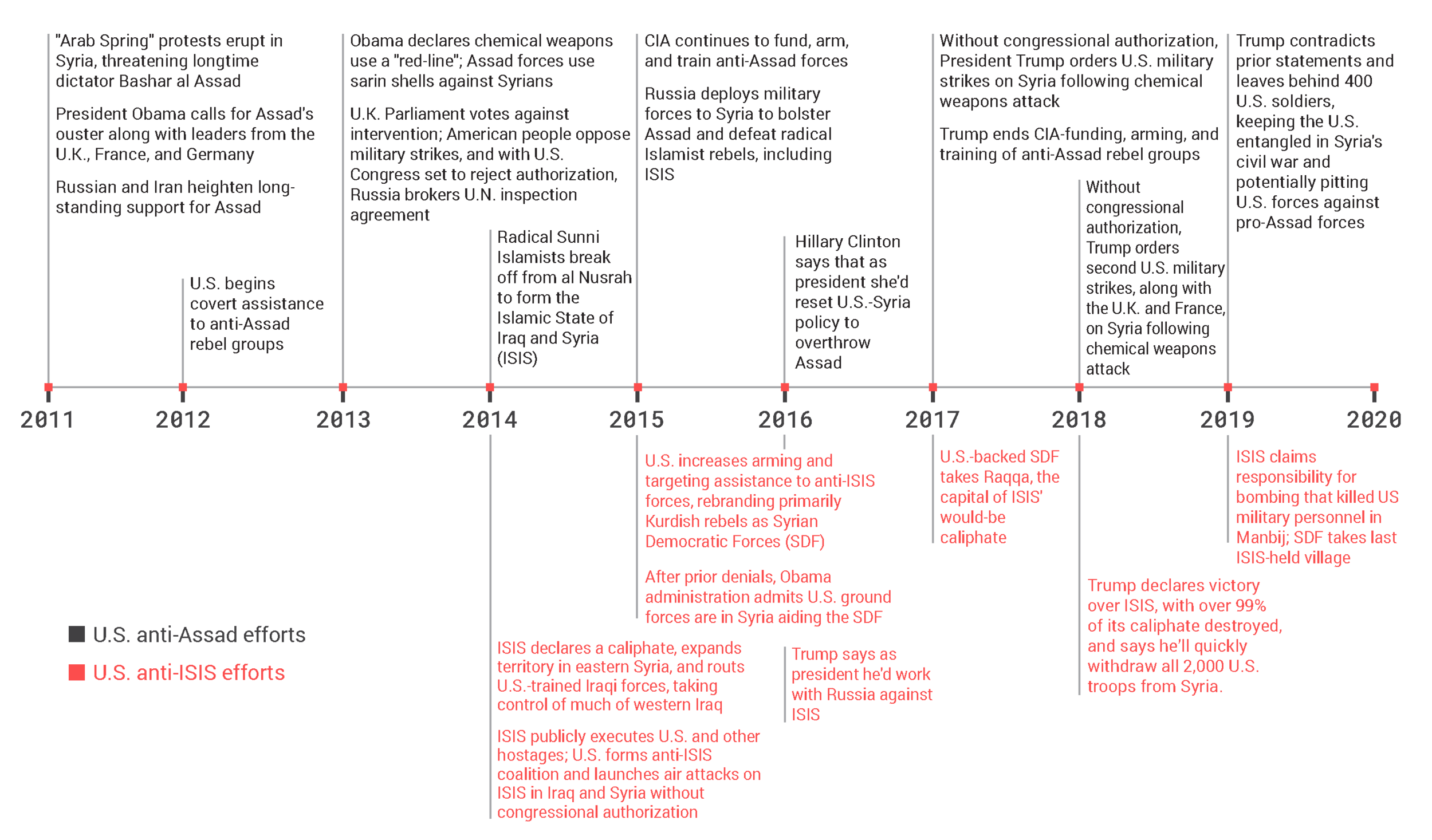

Timeline of U.S. involvement in Syria’s civil war

U.S. intervention in Syria preceded ISIS’s rise, but direct U.S. military engagement continues despite the successful campaign to liberate ISIS-held territory, which ended March 2019.

ISIS, however, will continue as a Sunni insurgency in Iraq and Syria. The weak governance in Iraq and Syria, and the dominance of those governments by non-Sunni Muslims, will make some continued jihadist insurgency likely, whether or it continues to call itself ISIS. ISIS’s remains will continue to claim credit for the attacks by its global affiliates, regardless of how little it actually controls them. With modern mass communications allowing propaganda to cross borders instantly, military force cannot destroy the ideology that drives a group like ISIS, as long as new converts can be found more quickly than they are attrited. This explains why two decades of the Global War on Terror has actually increased the number of anti-U.S. terror groups.

At its peak, ISIS controlled an army of perhaps 60,000, reportedly including 30,000 foreign fighters.1 Its battlefield leaders blended irregular tactics, like suicide vehicle-borne improvised explosive devices (SVBIEDs), with the expertise of some of Iraq’s remaining Sunni officer class.2 The brutality of its army also gave it a psychological edge, especially against a poorly-motivated enemy (the Iraqi forces U.S. military trained for years). That advantage culminated in the surrender of Mosul, a city of nearly two million inhabitants, and the effective collapse of four divisions of U.S.-supported Iraqi Army troops in June 2014.

Destroying the caliphate required block-by-block urban fighting, especially in Mosul, Iraq, and ISIS’s capital of Raqqa, Syria. In this campaign, the U.S. primarily contributed airpower, while local partners took the lead on the ground war. The Battle of Mosul took more than nine months, while the operation to isolate and then reduce Raqqa lasted nearly a year. The Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) alone lost more than 11,000 fighters during the campaign. When it was over, however, ISIS’s hybrid army had been shattered.

Despite the caliphate’s fall, however, U.S. forces deployed to Iraq and Syria for the anti-ISIS mission did not depart. Washington shifted the mission from a legitimate military aim to murky and unclear goals: denying the Assad regime control of a large portion of Syria, and in Iraq to “contain” Iranian influence (which is a direct result of the U.S. invasion and introduction of electoral democracy).

ISIS still boasts perhaps 18,000 members in Iraq and Syria—not all of whom are actually fighters.3 These diehards conduct assassinations, bombings, crop burnings, and other attacks on security forces and civilians in both countries. Most attacks are conducted by fewer than a dozen fighters and take place in rural areas, not centers of government power.4 The security forces of both Iraq and Syria have been reconstituted and—along with other regional actors—are capable of countering this dispersed and low-intensity threat. ISIS’s post-caliphate terror campaign is a problem but not a major threat to Syrian or Iraqi states.

Assessing the threat of ISIS’s remnants

ISIS maintains some support in the traditional heartland of Iraqi Sunni insurgency: Anbar, Ninewa, Salah ad Din, Kirkuk, and Diyala Provinces. Scattered media reports suggest that ISIS is regaining strength via “safe havens” in rural and mountainous regions of Iraq.5 NBC News reported in November that some ISIS fighters had ensconced themselves in the Makhmour District in northern Iraq, exploiting a seam between the Iraqi army and Kurdish peshmerga.6 Small groups of ISIS fighters—generally a dozen or fewer—conduct small-scale attacks and hide out from attacks by Peshmerga and Iraq state forces.

In theory these ISIS fighters have access to a war chest of between $50 and $300 million.7 This is a significant sum for a terrorist group, but it amounts to less than one-fifth of ISIS’s annual revenue at its peak. It is unclear how ISIS fighters can access these funds today. ISIS has also lost control over Syria’s oil fields, once a significant source of revenue for the group.

ISIS’s remnants are really a problem with at least three facets: remaining ISIS fighters in Iraqi and Syrian territory, foreign jihadist volunteers who may return to the West and continue the fight, and ISIS prisoners in detention camps—many of whom are women and children.

ISIS’s survivors—of whom perhaps 2,000 have returned to Europe—are a potential terrorist threat to Europe. Lone wolf attacks continue (like the recent one at London Bridge), though a predicted 2019 wave of terror didn’t occur.8 ISIS’s ability to direct and control these lone wolf jihadis is likely low.

ISIS foreign volunteers, however, are not a serious threat to the U.S. There are just 16 known American Syrian jihad returnees, most of whom came back in chains.9 Every terror attack since 9/11 that killed Americans on U.S. soil was carried out by a U.S. citizen or permanent legal resident.10 Distance and stringent U.S. homeland security measures implemented over the last two decades create a formidable barrier for the small number of terrorists with the capability and intent to attack the U.S. There have been just seven successful foreign terrorist attacks on U.S. soil since 9/11. The odds of an American being killed in such an incident are 1 in 140 million.11 By comparison, the odds of being struck by lightning are 1 in 700,000.

In the wake of Turkey’s incursion into northeastern Syria, the security of the detention camps holding up to 80,000 ISIS members and their families is important.12 The mass release of detainees would boost ISIS’s attempts to rebuild. This is a complex problem with security, aid, and legal ramifications.13 It is not, however, a mission for U.S. troops but one that local actors should cooperate to manage.

The limited threat of a post-caliphate ISIS

The specter of a renewed ISIS safe haven in Iraq, Syria, or elsewhere is wielded by defenders of continued and enduring U.S. military intervention. This argument conflates two very different things: small, rural ungoverned spaces in conflict zones and a protostate of millions with the ability to administer and levy taxes. The former is inevitable as long as weak governance is the norm in Iraq and Syria and provides limited advantages to terrorists in an age of porous borders and the internet.14 The latter is a real threat.

Control of a state—de facto or de jure—grants enormous manpower, revenue, and perhaps most important, symbolic prestige and branding that aids in recruitment. ISIS’s physical caliphate, an embryonic state governed according to the group’s medieval version of Islam, provided a global example and rallying point for disaffected Muslims, particularly in Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East. The caliphate, however brutal and tenuous, provided proof of jihadist victory for those who wanted to see it. The victories attracted recruits from around the world while the territory gave them a place to go and live.

Ungoverned spaces, on the other hand, provide no such advantages. At worst, they enable limited training of terrorists and insurgents and some small-scale sources of illicit income. Contrary to Washington’s conventional wisdom, most ungoverned spaces do not export their chaos in any significant way. Many potential terrorists find themselves fighting for their lives against both their own governments (however limited) and rival militant groups.15

ISIS-held territory in Iraq and Syria

The U.S.-led coalition destroyed the last remnant of ISIS’s caliphate in March 2019. That attainable military mission removed the threat posed by the radical Islamist protostate. ISIS’s remnants, however, pose nowhere near the same threat and do not justify prolonging the U.S. military mission.

Neither U.S. forces nor U.S. “partners”—even by the most generous definition of that term—are entirely able to prevent ungoverned spaces from appearing. Many states, especially in the Middle East and Africa, simply lack a monopoly on violence throughout the entirety of their territory.

A terrorist state, as the ISIS caliphate briefly was, is more than an ungoverned space. Such an entity is a real, though not existential, threat to the West. The campaign against ISIS’s caliphate was an appropriate use of U.S. power, though absence of congressional authorization and its prosecution by local partner forces are both deserving of criticism. In the absence of will or capability by regional actors, a future jihadist state could justify an acute, devastating U.S. expedition, as exemplified by the initial overthrow of the Taliban following the attacks on 9/11.

ISIS can only be completely destroyed by local forces

No Middle East power wants to see ISIS return. Syria (backed by Russia), Iraq, Iran, the Kurds, Hezbollah, and a host of lesser proxy forces have fought and bled to destroy the Islamic State.16 Even Erdogan’s Turkey, rightly excoriated for turning a blind eye to the growth of ISIS before 2015, has suffered major ISIS attacks. Turkey can be justly accused of negligence in regard to the initial growth of ISIS, but not actual support or collusion.

The inconvenient truth is Iran and its proxy forces played a critical role in defeating ISIS in both Iraq and Syria. Shiite forces, including Lebanese Hezbollah and Pakistani and Afghan units, stiffened Bashar al-Assad’s military at critical points, while Iraq’s Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) defended their country from being overrun by ISIS in late 2014. By contrast, Iraq’s regular army—stood up, trained, and supported by the U.S.—melted in the face of ISIS, with four entire divisions abandoning their posts.17

All of these state and non-state forces have a strong interest in opposing ISIS, and all of them have far more skin in the game than the United States. All of them also have far more combat power than ISIS. In the event of an ISIS resurgence that cannot be handled completely by local actors, the U.S. can play a supporting role by providing air support and supplying anti-ISIS factions with heavy weaponry, as in the recently concluded campaign. Only the full-blown return of an ISIS caliphate should justify the re-insertion of U.S. combat troops. In that unlikely event, U.S. forces should be immediately withdrawn upon completion of that narrowly defined military mission.

Washington’s failed post-9/11 wars point to the key issue in destroying ISIS: An insurgency can only suffer enduring defeat at the hands of the government it attempts to overthrow and only with brutal tactics no liberal society would sanction. Third-party counterinsurgency, which our enduring U.S.-driven campaign in Syria or Iraq is, has a historical track record of such failure. The U.S. debacles in Afghanistan and Iraq are only the latest examples. Vietnam (twice), Algeria, and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan are other expeditionary counterinsurgency wars that ended in humiliating defeat for the outside powers.18

Local security forces—and the governments and societies that man, pay, and empower them—are the best solution to Sunni insurgency in the Middle East. As the failure of both Iraqi and Afghan security forces in 2014 demonstrated, even a decade-long U.S. effort costing hundreds of billions of dollars to stand up local armies is woefully inadequate without legitimate local will to fight.

Armed factions in Iraq and Syria oppose and outnumber ISIS

ISIS, a minor presence, is opposed by the many armed factions competing for power in Iraq and Syria.

Governance is also critical. An insurgency can either be repressed to the point of annihilation, as in Sri Lanka, or defeated through compromise, negotiation, and some concessions to address root causes, as in Northern Ireland.19 Iraq and Syria are more likely to take the former option, though Assad’s local truces throughout the Syrian civil war show that a combination of stick and carrot is usually possible. It is notable that Idlib Province, where ISIS founder Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi was killed, remains the one major piece of Syria not under government control.

However, Bashar al-Assad’s rapprochement with the Kurdish YPG and the continued military capability of Iraq’s Kurdish peshmerga also indicate the seams for an ISIS resurgence remain thin. U.S. military presence—and diplomatic pressure—actually stalled this deal and delayed the region’s return to a strategic equilibrium.20 Though an uglier one than we might wish, Assad and the Kurds are a solution to what remains of ISIS in Syria. There are ample military forces in the field to counter ISIS, and, absent a full unraveling of Iraq’s government, they are likely sufficient to keep ISIS violence to a manageable level.

The U.S. role in countering ISIS

Past predictions of ISIS’s irrelevance or demise have been premature: President Obama famously labeled ISIS “a JV team” less than six months before the group began its 2014 blitzkrieg through Syria and Iraq.21 ISIS is likely to remain a local security challenge that can best be managed by regional actors.

The best thing the U.S. can do is remove U.S. forces from harm’s way. A limited force of 500 soldiers can achieve nothing of strategic value for U.S. security but is vulnerable to reprisals from Iran, amid “maximum pressure,” and local forces anxious for the U.S. to leave.

Ostensibly now aimed at protecting Syria’s oil from falling into the hands of ISIS, the mission creep in U.S. policy is aimed at countering Assad and Iran.22 ISIS’s ability to seize Syria’s oil fields is doubtful and any oil would have to be smuggled through hostile Iraq, Turkey, or Syria. What this policy really does is inhibit Syrian reconstruction—a process that actually could destroy any chance of an ISIS resurgence. Washington’s refusal to accept Bashar al-Assad’s victory in the Syrian civil war aids ISIS—U.S. withdrawal would benefit U.S. security and humanitarian aims.

To best counter ISIS’s potential resurgence, the U.S. should:

- Remove all U.S. forces from Syria and accept the unfortunate reality that Assad will remain in power and Syria’s forces are best suited to the task of ISIS’s suppression in Syria. Keeping a foothold, and especially denying the Syrian state oil revenues, prolongs the violence, encourages Balkanization, and inhibits reconstruction in Syria.

- Remove all U.S. forces from Iraq, in accordance with the end of the mission to defeat the caliphate—even if the Iraqi government invites the U.S. to stay. These U.S. troops are vulnerable to Iranian retaliation, and their presence keeps Shiite militias focused on them rather than destroying the remnants of ISIS.

- Avoid escalation that would bring the U.S. into direct conflict with Iran or its proxy militias in Iraq. These entities, while hostile to U.S. forces in country, provide a natural counterbalance to Sunni radicals. Their collapse would pave the road for a resurgent ISIS or equivalent radical Sunni entity.

- Ensure ISIS detention centers, especially at Al Hol, do not release prisoners through diplomacy and coordination with the dominant factions on the ground in Syria.

- Use diplomatic and financial tools to compel other countries to repatriate, punish, and deradicalize all foreign ISIS fighters and their families.

- Preempt legitimate anti-U.S. threats through targeted raids and military strikes.

- Use the U.S. military’s global intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance, and strike (ISR-Strike) capabilities to monitor and disrupt an anti-U.S. terror threats emanating from Iraq, Syria, and the broader region. 23

Should ISIS reconstitute its physical caliphate, and should Congress authorize the mission, the U.S. can project significant combat power in a devastating but discrete punitive expedition. In the meantime, the “dangerous dregs of ISIS”24 should not justify mission creep and another forever war that drains U.S. power in the Middle East. The situation in Iraq does not justify the deployment of U.S. troops, especially when those troops are vulnerable to Iranian proxies and missiles.

The U.S. has higher priorities at home and arguably in Asia—a few thousand insurgents in nonessential states should not occupy nearly this much U.S. attention.

Endnotes

1 Efraim Benmelech and Esteban F. Klor, “What Explains the Flow of Foreign Fighters To ISIS?” National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 22190 (April 2016), http://www.nber.org/papers/w22190; Samia Nakhoul, “Saddams’ Former Army is Secret of Baghdadi’s Success,” Reuters, June 16, 2015, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-mideast-crisis-baghdadi-insight/saddams-former-army-is-secret-of-baghdadis-success-idUSKBN0OW1VN20150616.

2 Ben Hubbard and Eric Schmitt, “Military Skill and Terrorist Technique Fuel Success of ISIS,” New York Times, August 27, 2014, https://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/28/world/middleeast/army-know-how-seen-as-factor-in-isis-successes.html.

3 Anthony H. Cordesman and Abdullah Toukan, with the assistance of Max Molot, “The Return of ISIS in Iraq, Syria, and the Middle East,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, Working Draft, September 3, 2019, https://www.csis.org/analysis/return-isis-iraq-syria-and-middle-east.

4 Eric Schmitt, Alissa J. Rubin, and Thomas Gibbons-Neff, “ISIS Is Regaining Strength in Iraq and Syria, New York Times, August 19, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/08/19/us/politics/isis-iraq-syria.html.

5 Schmitt, Rubin, and Gibbons-Neff, “ISIS is Regaining”; Orla Guerin, “ISIS in Iraq: Militants ‘Getting Stronger Again,’” BBC News, December 23, 2019, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-50850325.

6 Courtney Kube, “‘Defeated’ ISIS Has Found Safe Haven in an Ungoverned Part of Iraq,” NBC News, November 4, 2019; Paul Pillar, “The Safe Haven Notion,” The National Interest, August 29, 2017, https://www.nbcnews.com/news/mideast/defeated-isis-has-found-safe-haven-ungoverned-part-iraq-n1076081.

7 Cordesman, Toukan, and Molot, “The Return of ISIS in Iraq, Syria, and the Middle East.”

8 Jason Burke, “New Wave of Terrorist Attacks Possible Before End of Year, UN Says,” The Guardian, August 3, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/aug/03/new-wave-of-terrorist-attacks-possible-before-end-of-year-un-says.

9 Ari Shapiro, “What Happens when Americans who Joined ISIS Want to Come Home,” All Things Considered, National Public Radio, February 21, 2019, https://www.npr.org/2019/02/21/696769808/what-happens-when-americans-who-joined-isis-want-to-come-home.

10 Alex Nowrasteh, “Terrorists by Immigration Status and Nationality: A Risk Analysis, 1975–2017,” Policy Analysis No. 866, The Cato Institute, May 7, 2019, https://www.cato.org/publications/policy-analysis/terrorists-immigration-status-nationality-risk-analysis-1975-2017.

11 Nowrasteh, “Terrorists by Immigration Status.”

12 Jane Arraf, “Families of ISIS Fighters Crowd Camps in Syria,” Weekend Edition Saturday, National Public Radio, March 30, 2019, https://www.npr.org/2019/03/30/708302371/families-of-isis-fighters-crowd-camps-in-syria.

13 Jessica Trisko Darden, “The Al-Hol Case: Left-Behind ISIS Adherents Pose a Unique Challenge,” Real Clear World, July 30, 2019, https://www.realclearworld.com/articles/2019/07/30/the_al-hol_case_left-behind_isis_adherents_pose_a_unique_challenge_113066.html.

14 See Micah Zenko and Amelia Mae Wolf, “The Myth of the Terrorist Safe Haven,” Foreign Policy, January 26, 2015, https://foreignpolicy.com/2015/01/26/al-qaeda-islamic-state-myth-of-the-terrorist-safe-haven/.

15 See countless examples of jihadist fratricide from Syria’s civil war and the Taliban—ISIS-K conflict. Thomas Gibbons-Neff and Julian E. Barnes, “U.S. Military Calls ISIS in Afghanistan a Threat to the West. Intelligence Officials Disagree,” New York Times, August 2, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/08/02/world/middleeast/isis-afghanistan-us-military.html.

16 Benjamin Friedman and Justin Logan, “Disentangling from Syria’s Civil War: The Case for U.S. Military Withdrawal,” Defense Priorities, March 2019, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/disentangling-from-syrias-civil-war.

17 Eric Schmitt and Michael R. Gordon, “The Iraqi Army Was Crumbling Long Before Its Collapse, U.S. Officials Say,” New York Times, June 12, 2014, https://www.nytimes.com/2014/06/13/world/middleeast/american-intelligence-officials-said-iraqi-military-had-been-in-decline.html.

18 Eliot Cohen, “Constraints on America’s Conduct of Small Wars,” International Security 9, no 2. (Fall 1984): 151–181.

19 See T.X. Hammes, The Sling and the Stone: On War In the 21st Century (New York: Zenith Press), 2006; Lionel Beehner, “What Sri Lanka Can Teach Us About COIN,” Small Wars Journal, August 27, 2010, https://smallwarsjournal.com/jrnl/art/what-sri-lanka-can-teach-us-about-coin.

20 Christopher Dickey and Spencer Ackerman, “The U.S. Spoiled a Deal That Might Have Saved the Kurds, Former Top Official Says,” The Daily Beast, October 14, 2019, https://www.thedailybeast.com/the-us-spoiled-a-deal-that-might-have-saved-the-kurds-former-top-official-says.

21 “Barack Obama,” Meet the Press, NBC, September 7th, 2014, https://www.nbcnews.com/meet-the-press/meet-press-transcript-september-7-2014-n197866.

22 Helene Cooper, Julian E. Barnes, Eric Schmitt, and Thomas Gibbons-Neff, “Trump and the Military: A Dysfunctional Marriage, But They Stay Together,” New York Times, November 14, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/14/us/politics/trump-military.html.

23 Defense Priorities, “Counter Anti-U.S. Terror Threats with Targeted Raids, Not Permanent Occupations,” October 2019, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/counter-anti-us-terror-threats-with-targeted-raids-not-permanent-occupations.

24 Robin Wright, “The Dangerous Dregs of ISIS,” New Yorker, April 16, 2019, https://www.newyorker.com/news/dispatch/the-dangerous-dregs-of-isis.