Securing U.S. interests while avoiding a war with Iran

May 30, 2019

Vital U.S. interests in the Middle East are narrow

Preventing significant, long-term disruptions to the global oil supply

Eliminating anti-American terrorists with the capability and intent to attack the U.S.

Minimal U.S. effort is required to protect regional interests and contain Iran

There is no threat of a dominant regional power (hegemon) in the Middle East that could substantively disrupt global energy markets; the U.S. could not pacify Iraq after a decade and more than $2 trillion; Iran is far too weak to dominate its neighbors

The U.S. should not pick sides in the Middle East’s Sunni and Shiite power struggles; it should not confront Iran or Saudi Arabia on the other’s behalf; U.S. intervention in the region’s civil wars exacerbates and prolongs those conflicts (see Iraq, Syria, and Yemen)

Iran’s malign activity is troublesome but not unique—if anything, Gulf states have done more to aid terrorists, particularly radical Sunni jihadis prone to strike the West, like Saudi Arabia’s funding of Wahhabism

Anti-American terrorist threats can be confronted through cooperation with local actors, intelligence and domestic security, and if necessary, congressionally-authorized strikes; the U.S. should end “endless wars” and force regional powers (including Iran) to confront its own problems, like local extremists

Assessing the threat from Iran—weak, contained, and of peripheral concern to the U.S.

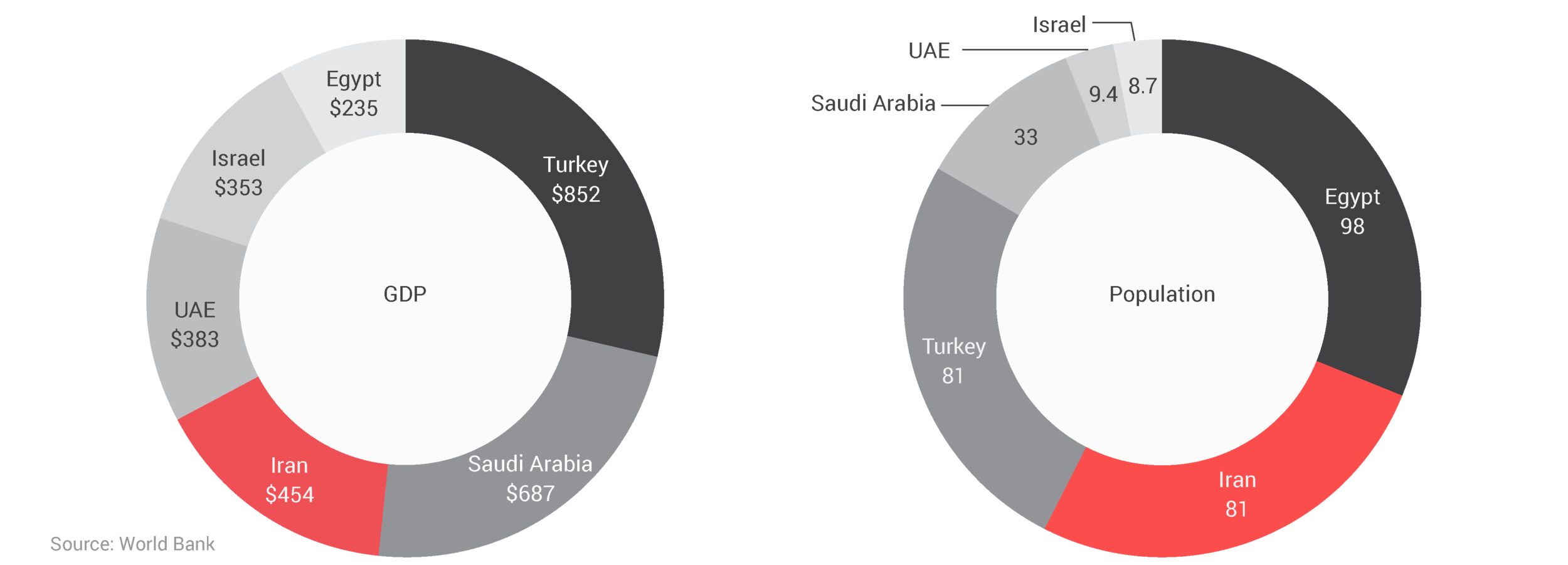

Iran by the numbers—GDP: $454B (the Pentagon’s budget is 50 percent greater than Iran’s entire economy); Population: 81.2M; military spending: $14.5B; active military personnel: 523,000 (including 125,000 IRGC forces)

Metrics for comparing economic, diplomatic, and military power in the Middle East

Iran is a middling power, contained by the region’s stronger powers. Saudi Arabia and the UAE cooperate closely, and to a lesser degree, cooperate with Israel and Egypt. Even Turkey has competing interests.

Conventional power—Iran is a middling power with an aging military checked by other regional powers: Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Egypt, and Israel; these powers often maintain close partnerships (Saudi and UAE) or cooperate when convenient against Iran (Saudi and Israel); Iran’s size, terrain, and resilience make it very costly to attack, but its ability to project power regionally is minimal

Supporting extremist groups—Iran’s support for Shiite militias reflects its weakness—it lacks conventional power and must rely on unsavory partners; this is problematic and worth addressing through diplomacy; these local groups do not threaten the U.S. homeland; the greater extremist threat comes from the Gulf states’ support for radical Sunni Islam, like Wahhabism

Malign behavior—Iran’s behavior abroad is bad but not unique among other powers in the region—its rival Saudi Arabia forcibly detained Lebanon’s prime minister; killed a dissident journalist abroad for opposing the regime; launched a prolonged bombing campaign in Yemen, fostering a humanitarian crisis; and carries out domestic repression comparable to, if not worse than, Iran’s

Nuclear weapons development—Negotiating a deal that fundamentally improves on the concessions Iran made in the JCPOA seems out of the question given current policy and the climate of mistrust; even if Iran stops its compliance and restarts nuclear weapons development, a preventive war would harm U.S. interests; in that case, military intervention is only justified to pre-empt an imminent attack, not to destroy Iran’s nuclear capability; the U.S. can deter Iran indefinitely, like it has China and Russia

Oil—Iran possesses 10 percent of the world’s oil reserves—enough to be a market force but nowhere near enough to manipulate its price; Iran has neither capability nor intent to seize oil fields elsewhere; it could, however, disrupt oil production and transportation region-wide if attacked (current U.S. policy is to reduce Iranian oil exports to zero, which is also a threat to global supply)

Four myths driving Washington’s hostility toward Iran

Myth: The Middle East is of vital strategic importance to the U.S. and requires a permanent military ground presence to manage

The Middle East was more strategically important during the Cold War because of U.S. reliance on the region’s oil and the perceived threat of Soviet hegemony (U.S.-Saudi ties hedged against this); today, the region is less central to global energy supply

Power in the Middle East is diffused among several nations; none can dominate the region, let alone Iran, which has shown no interest in territorial acquisition and lacks the capability; Israel, the greatest regional military power by far, can easily defend against any Iranian aggression

Political instability is a challenge but not one best managed with U.S. ground forces; Washington’s regime-change policies and military occupations have led to more violence and conflict, not less, at great human and economic cost to Americans

Myth: The U.S. cannot coexist with Iran as long as it’s led by “the Mullahs”

The U.S. and Iran have co-existed for 40 years since the Iranian revolution; Iran has never attacked another country and has a shared interest in confronting Sunni extremism; its bad behavior is not unique, and regional actors contain it

The U.S. should deal with the Iranian regime through deterrence and diplomacy; U.S.-imposed regime change (even by non-military means) would backfire, as previous efforts in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Libya demonstrated

Myth: Sanctions and “maximum pressure” will improve the regime’s behavior or spur Iranians to overthrow the regime

States balance against threats; at least some of Iran’s concerning actions, like developing missiles, can be attributed to feeling threatened and attempting to defend itself; if “pressure” seems like a threat, it is likely to backfire

U.S. threats and pressure will likely make Iran less cooperative, more prone to support extremists, and more eager to develop nuclear weapons; because nationalism makes people resist foreign powers’ demands, outside pressure and threats tend to heighten support for hardliners and hardline policies

In the wake of unilateral U.S. withdrawal from the JCPOA, Iranians view sanctions as increasingly harsh and unprovoked, making it politically difficult for Tehran to talk with the Trump administration, even if the regime wanted to negotiate

Sanctions are counterproductive to internal regime change prospects; economic pressure historically makes societies more authoritarian, repressive, and less democratic, as existing leadership denies their opponents scarce resources

Myth: Nuclear proliferation requires preventive actions, including war

Preventive war (offensive) to eliminate weapons capabilities—rather than to forestall an imminent attack (defensive)—encourages nuclear proliferation; it incentivizes nations to acquire nuclear deterrents to avoid regime change, to avoid the fate of former Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi

Arms control agreements, economic incentives, and improving trust and security limit nuclear proliferation at acceptable costs; regardless of its merits, the JCPOA showed Iran’s willingness to negotiate away key parts of its nuclear weapons program

Even if Iran acquired nuclear weapons, U.S. deterrence would hold, as with far greater powers, like China and Russia

“Maximum pressure” is more likely to lead to crisis or war with Iran than capitulation or negotiations

Withdrawing from the JCPOA despite Iran’s compliance, reinstituting crippling sanctions, designating the IRGC a Foreign Terrorist Organization (FTO), and issuing maximalist demands for future negotiations does not allow for diplomatic compromise

Iranian threats to restart its nuclear program are a sign of desperation to recapture the benefits promised to it through the JCPOA

A U.S-Iran war is likely to start in three ways: (1) a “preventive war” to take out Iran’s nuclear weapons capabilities; (2) a so-called “limited” or “targeted” U.S. response to an Iranian attack that escalates into a wider conflict (U.S. forces in Syria and Iraq could easily be entangled in a confrontation with an Iranian-linked militia); or (3) an accident or violent incident of uncertain origin

An alternate Iran policy that actually serves U.S. interests

Maintain deterrence—Iran is deterred; it understands it would lose any conflict with the U.S., but that doesn’t mean it will not respond if threatened; Washington should stop confusing Iran’s responses, like developing and deploying missiles, with aggression

U.S. military spending vs. Iran

The U.S. spends 47 times more than Iran ($14.5B) on its military. The DoD budget alone is 50 percent larger than Iran’s entire economy.

Avoid a costly, unnecessary war with Iran—Iran is a weak power that poses no direct threat to the U.S., but it could impose serious costs in the event of a war; a war on Iran could trigger anti-American terrorism among regional Shiite militias sympathetic to Iran, and further destabilize the Middle East, enhancing the recruiting and reach of various terrorist groups; the U.S. has higher priorities at home and arguably in Asia

Adopt an offshore, neutral approach—The U.S. should not pick sides in the current Iran-Saudi Arabia power struggle; Iran is guilty of malign activity but is not unique; the U.S. should recalibrate and normalize its relations with Middle East nations and reduce its footprint (currently more than 20,000 forces)

Remove all U.S. forces from Syria and Iraq—The greatest friction points for war are in Syria and Iraq; with ISIS’s caliphate destroyed, Washington should not leave soldiers behind in those countries to act as a tripwire for conflict with Iran; the U.S. should abandon its efforts at nation building, withdraw all troops, and instead monitor and target anti-American terrorists

Drop maximalist demands—Like the U.S., Iran faces domestic hardliners who oppose diplomacy; the U.S. should negotiate without preconditions and use confidence-building measures to encourage Iran to come to the negotiating table

Provide a diplomatic off ramp to “maximum pressure”—Coercion will lead to crisis or war before capitulation; to draw Iran back to the negotiating table, the Trump administration must rebuild trust; the U.S. and Iran should start by matching small, conciliatory gestures and progress to more substantial negotiations on more complex disagreements