Key points

The 2021 Global Posture Review now underway should move the nation toward a strategy of restraint for three reasons: the need for domestic renewal, the drawdown from counterterrorism wars, and allies’ ability to do far more to maintain stable balances of power in the world’s key regions.

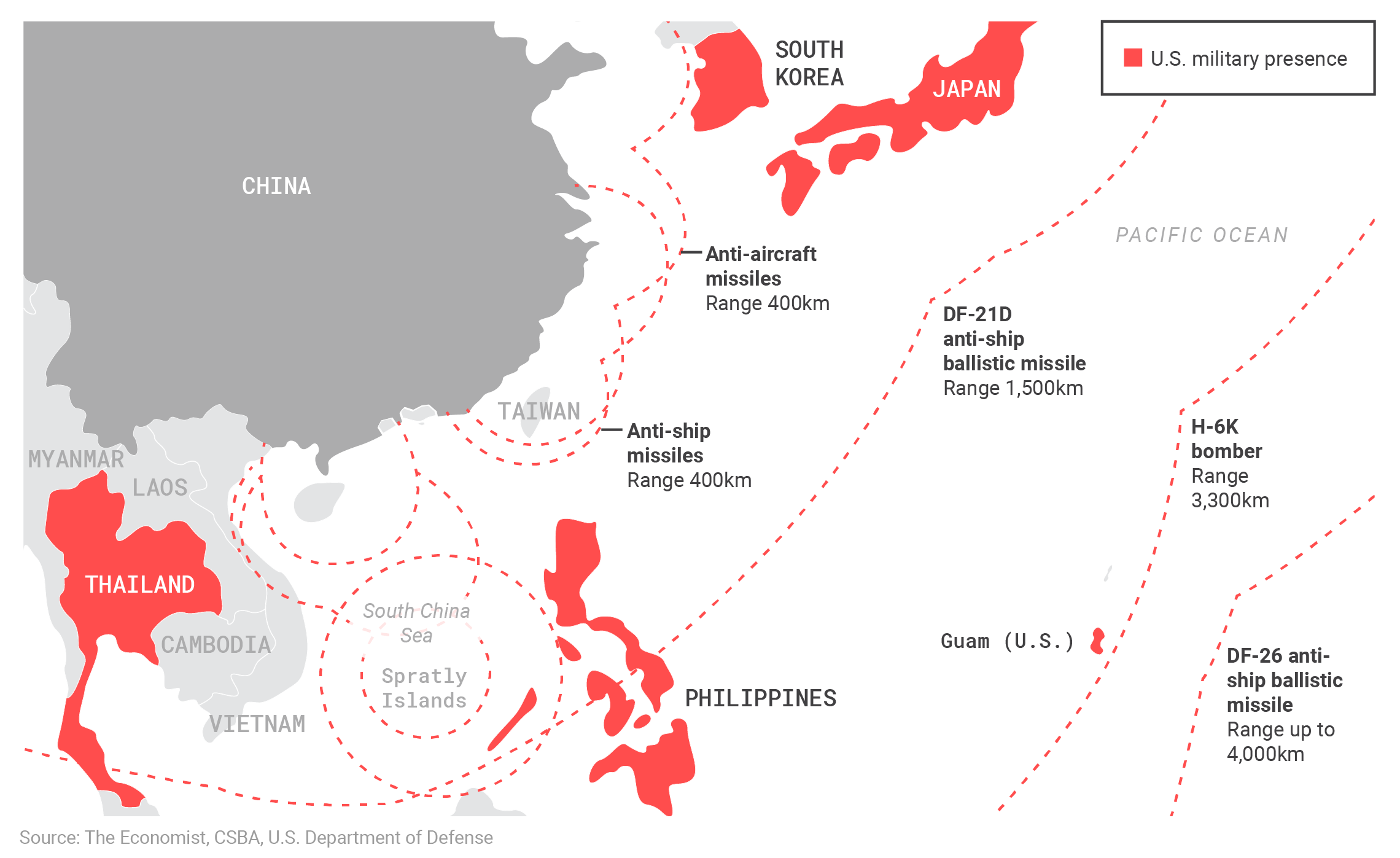

The increased accuracy of Chinese missiles calls the U.S. force posture in the Pacific into question. America should disperse and harden its forces in the region, push its allies to do more, and rely more heavily on long-range strike options to serve as a balancer of last resort.

European allies are wealthy and more than capable of preventing Russia from dominating Europe. U.S. forces in Europe can be significantly reduced.

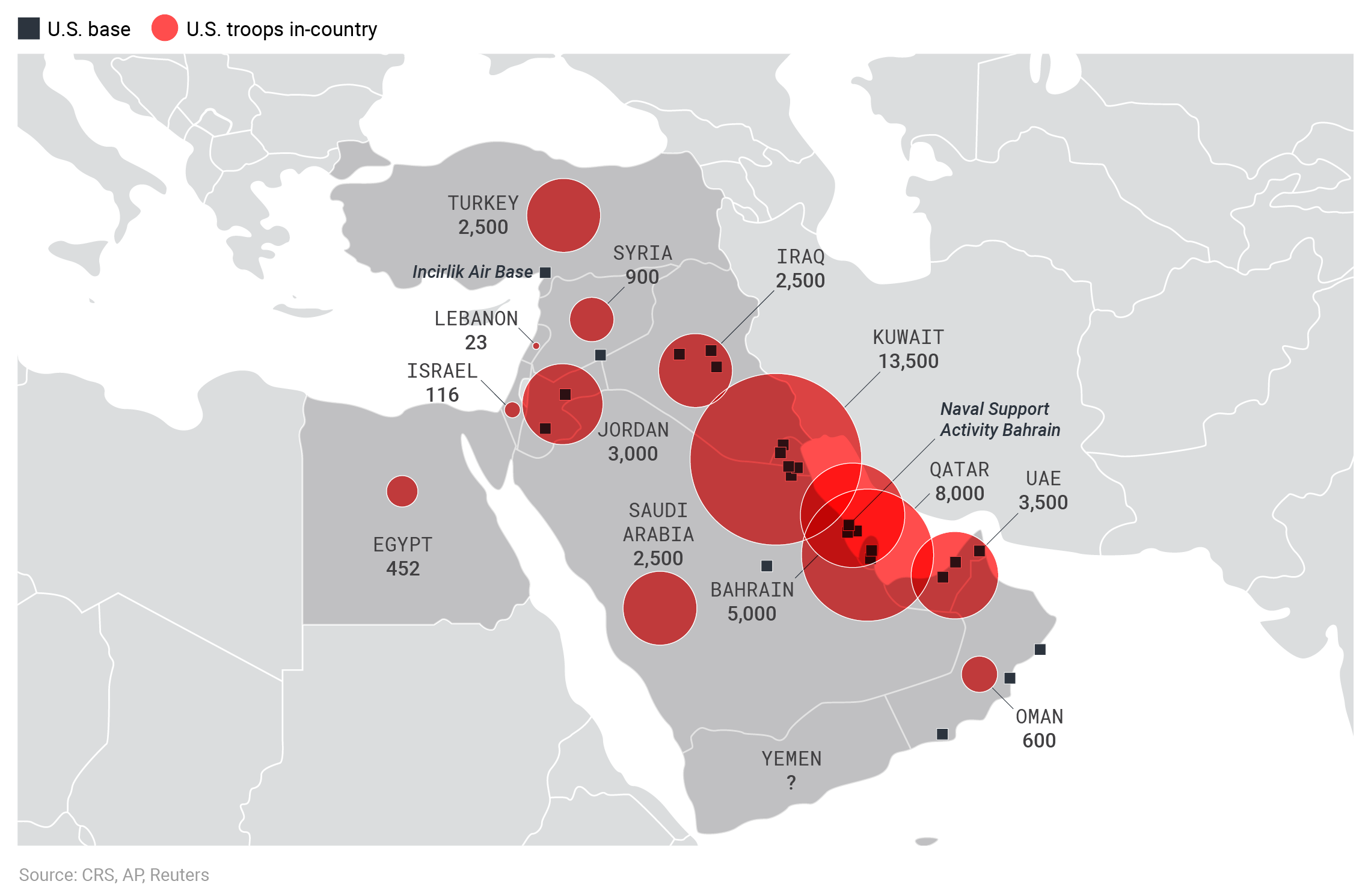

None of the major U.S. goals in the Middle East—countering terrorism, avoiding major oil supply shocks, and defending Israel from attack—require major U.S. bases in the region or a significant military footprint. The United States is overdue to minimize its military role in the Middle East.

High operational tempo continues to weaken the U.S. armed forces, burning through readiness and equipment and threatening personnel retention. The solution is not a bigger force but fewer missions.

What is a Global Posture Review?

On February 4, President Biden ordered Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin to lead a Global Posture Review of all U.S. forces deployed overseas to ensure that “our military footprint is appropriately aligned with our foreign policy and national security priorities.”1 The United States’ global defense posture encompasses the size, location, types, and capabilities of its forward-deployed military forces. Along with force structure, the U.S. global defense posture is a crucial element of American defense strategy and military planning.

An old saying in national defense circles goes, “Show me your budget, and I’ll tell you your strategy.” As true as that is, America’s national defense strategy is also demonstrated by where it deploys forces and maintains bases. Overseas bases enable the United States to project power by providing hubs for transportation and logistical sustainment. Air bases are the most obvious example, given the fuel and maintenance needs of modern military aircraft. Naval bases provide sites for refueling, replenishment, and repair, as well additional security for both vessels and crews. Land bases permit the staging of ground forces and maintenance and repair of weapons and vehicles. Some larger overseas U.S. Army bases, particularly in Europe, provide ample live-fire ranges and maneuver training areas. Smaller U.S. bases—known as “lily pads”—are more austere and facilitate partnered operations with local forces, especially in counterterrorism operations in Africa, Asia, and the Middle East.

The forthcoming review is an opportunity for a form of “zero-based budgeting” for the United States’ enormous list of overseas military commitments and infrastructure. It is true the posture review of 2004, like most strategy documents, was a vague exercise that led to minimal change.2 This review may well follow that pattern of being more a justification for the present set-up than a point of departure. But there are three good reasons why this review should reflect an effort to restrain U.S. global military activities by reducing bases.

First, the United States seems to be moving toward exiting the series of wars and military actions originally dubbed the “Global War on Terrorism,” at least when it comes to large military deployments in warzones in the greater Middle East. The most obvious manifestation of this is the withdrawal of U.S. forces from Afghanistan. But there are many other smaller commitments and bases of even more dubious importance.

On counterterrorism missions alone, U.S. troops operated in at least 85 countries from 2018 to 2020.3 The United States has hundreds of overseas military installations, ranging from tiny expeditionary lily pads to sprawling mini-cities.4 But the post-9/11 fixation on a large U.S. military presence in the Middle East is perhaps finally, fitfully, ending.

Second, there is an evident need, reflected in statements from the Biden administration, to focus resources more on domestic renewal than foreign affairs. As in so many other spheres of life, the COVID pandemic has been an accelerant here. In a time of exploding national debt, with a new administration that has promised that its highest priority is to “build back better” at home and that U.S. foreign policy must better serve the American middle class, the review offers a unique opportunity to reduce America’s swollen overseas military footprint.5

U.S. military and DoD personnel deployed overseas

The U.S. military maintains hundreds of thousands of personnel, and hundreds of bases to house them, far beyond U.S. borders.

Third, America’s global defense posture remains far larger and more expensive than what is required to protect vital U.S. national interests: the security of the U.S. itself, free passage in the global commons, the security of U.S. treaty allies, and preventing the emergence of a Eurasian hegemon. This last goal, which justified U.S. participation in World War II and much of the extensive basing infrastructure put in place during the Cold War, now requires far less U.S. effort than it did then.

Yet U.S. force posture remains largely a hangover of the Cold War; more than 80,000 U.S. servicemembers and Department of Defense (DoD) personnel remain in Europe, despite the fall of the USSR and the size and wealth of European NATO. U.S. forces can shift far more of the burden of maintaining the balance of power against Russia and China to wealthy allies.

If Secretary Austin and President Biden want to recalibrate America’s global military posture, they should be guided by four imperatives:

- Burden-sharing in the Pacific

- Recognizing that Europe can and should defend itself from Russia

- Minimizing America’s military presence in the Middle East

- Reducing deleterious operational tempo

Balance and burden sharing in the Pacific

- U.S. forces in Asia are vulnerable to Chinese missiles and airpower; increasing the U.S. military footprint in the western Pacific is unwise.

- America’s wealthy allies and partners should devote more resources to their own defense, none more so than Taiwan. They should focus especially on improving their anti-access and area-denial (A2/AD) capability.

- Instead of staging more forces in the western Pacific and planning more naval patrols close to China’s shores, the United States should adopt a robust, hedged defensive posture in Asia, focusing on long-range-strike options to aid allies should the need arise.

Doubling down on the language and thrust of the 2018 National Defense Strategy, the Biden Administration’s Interim National Security Strategic Guidance, released in March, zeroes in on the threat China poses to the international system: “It is the only competitor potentially capable of combining its economic, diplomatic, military, and technological power to mount a sustained challenge to a stable and open international system.”6 President Biden and his national security team rightly consider China the United States’ preeminent competitor.

The modernization and expansion of China’s military is roughly commensurate with China’s prodigious economic growth, but it should not be understated. China now boasts the world’s largest army, a larger fleet than the U.S. (though lighter and less capable), and a growing missile arsenal. While nothing compels war between China and the United States, China’s rise may not remain peaceful. China’s increasingly assertive actions, from fighting India in the Himalayas to sanctioning Australian goods, do not necessarily mean it is seeking territorial gains, but they do show a rising power unsatisfied with the American-led status quo in Asia.

China has gotten far better at defending itself by tying ISR (intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance) systems to a growing missile arsenal. This creates a potential denied area for attacking ships and aircraft within the range of China’s shore-based radar systems, which are key to guiding cruise missiles. Chinese airpower, both manned and unmanned, provides a further threat to U.S. forces and tactical infrastructure, with the threat increasing with proximity to China’s coast. China’s ballistic missile arsenal can target U.S. forces in the Pacific, bar submarines, potentially as far out as Guam. While the accuracy of China’s ballistic missiles is unproven, especially against moving targets like ships, it is undeniable that bases are growing more vulnerable to accurate missile strikes.7

The United States’ primary response to this problem has been to spend more money on military platforms in Asia, most recently in the form of the Pacific Deterrence Initiative (PDI), and to promise to send more forces to the region.8 President Biden is the third consecutive White House occupant to promote a reorientation of America’s strategic focus to the Pacific. But stationing more U.S. forces in the Indo-Pacific region is not likely to hinder China’s rise or enhance regional stability—it may indeed be counterproductive.

A 2017 analysis of a potential Chinese missile attack on U.S. forces in the Pacific, authored by two U.S. Navy officers, makes for grim reading: U.S. missile defenses overwhelmed, almost every fixed headquarters struck within minutes, all major airbases cratered, all pierside ships in Japan hit by ballistic missiles.9 In range of an arsenal of accurate missiles, a navy cannot ensure its survival by staying in port.

Analysts at the Pentagon’s Office of Cost Assessment and Program Analysis (CAPE) and Office of Net Assessment are also reportedly pessimistic about the survivability of U.S. forces facing Chinese missile and rocket attacks. CAPE argues for a Pacific posture based on stealth bombers and emerging long-range strike technology like hypersonic missiles.10

The vulnerability of U.S. forces in Asia argues against reinforcing the current laydown of U.S. troops, ships, and planes in the western Pacific. U.S. forces stationed on the territory of treaty allies are primarily tripwire forces—there to ensure that both the United States and its allies are committed in the event of a shooting war with China.

China’s A2/AD capabilities and the U.S. military presence in East Asia

The potential range and accuracy of Chinese missiles means the U.S. should avoid consolidating large numbers of troops in static locations in the region.

Some combination of survivability enhancements, dispersion, and deception must be ready in the event of war to minimize the immediate attrition of those U.S. forces and their allies. In Japan, for example, the United States should insist on being able to disperse its planes across Japanese air bases and civilian airfields in the event of heightened tensions with China.11

The land services are attempting to justify an increased role in the maritime Asian theater. The U.S. Army and Marine Corps are both formulating ambitious plans to fight close in the Pacific, inside Chinese weapons engagement zones (WEZs).12 These plans, island-hopping in reverse, aim to seed friendly islands with small U.S. detachments to threaten Chinese ships and close off sea lanes. There is reason to be skeptical of this attempt to give land forces a prominent role in a potential Pacific war. Before the U.S. begins to operationalize these concepts, the DoD must be satisfied the logistical and command-and-control challenges to this concept are not insurmountable. War games and simulations have a deservedly mixed reputation, especially when they concern military services competing for shares of flat or declining defense budgets.13

A major increase in missile defense systems would lessen the damage from a Chinese missile barrage, though the exchange ratio would still favor the People’s Liberation Army Rocket Force. But China’s missile threat argues for basing the preponderance of U.S. Pacific forces where they can be protected—beyond the “third island chain,” in Guam and Hawaii—and preparing for a long war of attrition with the People’s Republic of China.

Such a war would probably require the U.S. Navy to fight its way back into the western Pacific, whether to defeat the People's Liberation Army Navy in battle or to strangle China through a blockade of its energy imports. In any event, given anticipated attrition to air and naval forces in U.S. Indo-Pacific Command and the limited U.S. shipbuilding industrial base, U.S. allies must be prepared to hold out without substantial U.S. support for what could be weeks or even months.14

The simplest way for the United States to respond to the Chinese threat is to push Asian allies to arm themselves with thousands of cruise and ballistic missiles. The U.S. should mimic China in making its missiles as mobile as possible, enabling survivability and thus increasing deterrence.

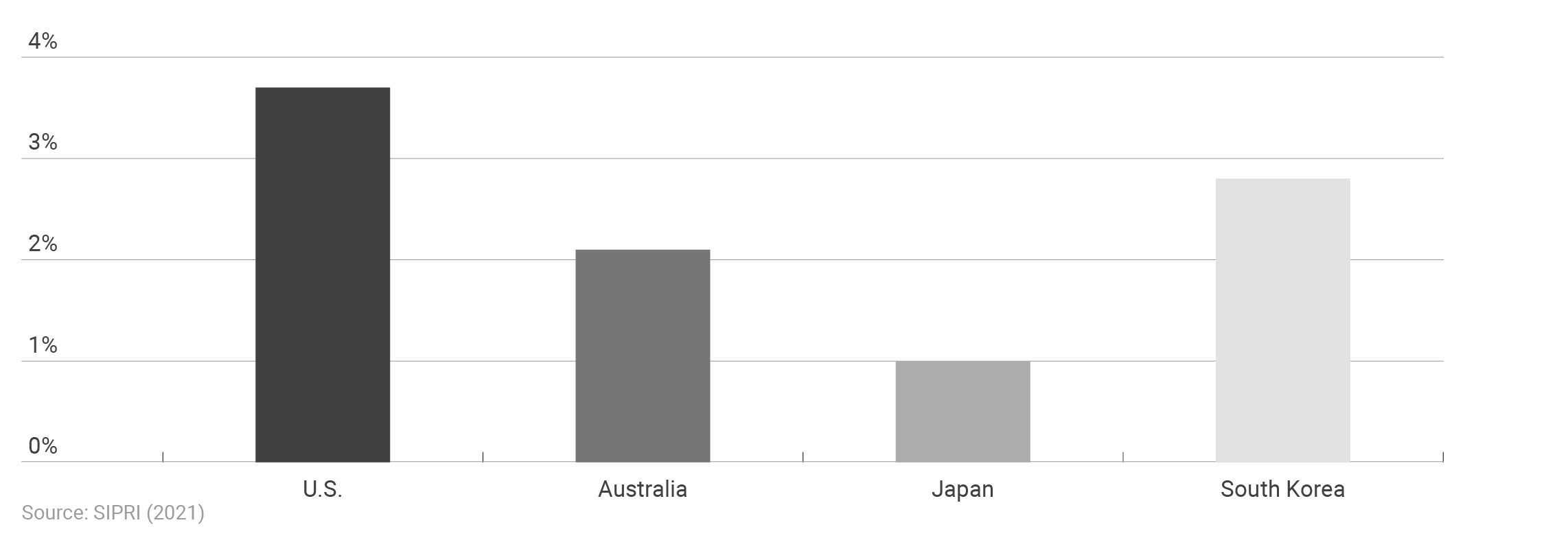

U.S. and major Indo-Pacific allies’ defense spending as a share of GDP

As a share of GDP, U.S. military spending far outpaces spending by major allies in the Indo-Pacific, suggesting that allies have the capacity to increase spending and provide more for their own defense.

The United States must also pursue policies that require its Pacific allies to increase their commitment to their own defense. Japan and Australia are wealthy countries that field modern, well-trained forces used to working with the U.S. military. Their problem is not capability but capacity. The United States must rely on these allies pulling their weight, particularly in the maritime domain, to balance a large and growing Chinese threat.

Taiwanese defense spending as a share of GDP

Taiwan’s defense spending has fallen as a share of its GDP since the 1990s. It has the capacity to increase spending if it perceives an increased threat of invasion from China.

Taiwan must reform

Various commentators have recently proposed discarding strategic ambiguity, the long-standing policy where the United States does not say if it will defend Taiwan from Chinese attack, in favor of an unambiguous commitment.15 This would be a mistake, not least because it could dissuade Taiwan from committing far more seriously to its own defense and broader societal resilience.16 Taiwan’s military, once a well-trained and serious force, has failed to keep pace with China’s. In 2017, Taiwan reduced its conscription term of service to a wholly inadequate and basically symbolic four months. Taiwan’s reserves, supposedly two million men strong, have been described as “a pure fantasy”: poorly organized, armed only with rifles, and commanded by inexperienced officers.17

Taiwan’s geography gives it enormous advantages in a war or even a non-kinetic confrontation with China. Missile and mine technology is making amphibious invasion even more difficult. Not only is Taiwan an island nation, but its limited beaches and strong tides severely constrain Chinese invasion options, with reliably good conditions for an amphibious landing only available two months out of the year.18 If Taiwan can be induced to become a true nation in arms on the Israeli or Finnish model, the odds of a successful Chinese invasion or blockade will drop substantially. Taiwan should be pressured to return to a minimum of a one-year conscription term, to toughen standards and training, and to make its reserves a viable military force through regular call-ups and exercises. It should invest more heavily in surveillance systems and mobile cruise missiles.19 Sustained pressure on allies, not enhanced forward military presence, is currently the United States’ most powerful weapon in the Pacific.

European nations should defend Europe

- NATO’s European members have the wealth and population to more than match Russia’s defense spending and military capability. They should be responsible for their own defense.

- NATO should not focus on out-of-area operations, let alone military competition with China. European nations should focus on Russia and their own defense, freeing U.S. resources for the Indo-Pacific.

- The United States should substantially, if gradually, reduce its military footprint in Europe.

America’s global alliance structure is a unique U.S. advantage. No other power has the breadth and depth of allies and partners that the United States enjoys around the world. American allies provide the United States with intelligence and situational awareness, basing and overflight rights, and additional combat power in the event of war.

These alliances and partnerships, however, mostly date from the Cold War era, and especially the immediate post-World War II period of unfettered U.S. hegemony. The U.S. economy’s share of global GDP peaked in the two decades after World War II at around 40 percent and has since fallen closer to 25 percent. U.S. alliances and partnerships have not reflected this change. As a result, many of these nations more closely resemble clients than partners—and many are free-riding on American security guarantees and forward-deployed forces.

Nowhere is this more clear than in Europe. Ravaged by war when the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) was founded in 1949, Europe is now the richest continent on earth. NATO had 16 member states at the conclusion of the Cold War. With the accession of North Macedonia in 2020, the alliance now has 30 members. The politics of past and future NATO enlargement are beyond the scope of this paper, but the current defense expenditures and capabilities of NATO members are extremely relevant to the United States’ global force posture. Just one-third of the alliance’s members meet the arbitrary benchmark of spending 2 percent of GDP on defense. As one retired U.S. naval officer recently wrote, most NATO states are either “Show Ponies,” spending too little but at least buying effective equipment, or abject "Free Riders."20

Most of NATO’s purported “War Horses” are barely clearing the 2 percent hurdle, with post-COVID cuts likely to come. The balance between capability and capacity also varies greatly among NATO members. Greece, for example, fields a large but ill-equipped garrison army that is more of a jobs program than an expeditionary force. In contrast, even as it devotes more money to defense, the United Kingdom is cutting 10,000 servicemembers from its total force by 2025. This will leave the British military the smallest it has been since the Napoleonic Wars.21

NATO’s only potential adversary takes its defense more seriously. The Russian military, a hollow force after the USSR’s dissolution, has undergone dramatic reform and rejuvenation over the past decade. Vladimir Putin and his regime, aided by high oil prices until recently, have stopped the bleeding and at least halted Russian decline. In some areas, like heavy artillery and electronic warfare, Russian capabilities likely exceed those of the United States and NATO.22 Russia’s economic and demographic difficulties are also often overstated.23

Russia’s defense spending is frequently underestimated. As the University of Birmingham’s Richard Connolly showed in a 2019 paper, Russia is consistently the fourth-largest military power in the world by purchasing power parity (PPP) annual expenditure.24

Russia and NATO-Europe’s defense spending (PPP) and active military personnel

Measuring Russia’s annual military spending in PPP avoids understating Russian power, yet NATO-Europe’s combined spending still outpaces Russia’s, as does its number of active military personnel.

Excluding the United States, Canada, and an increasingly obstreperous Turkey, NATO still fields about 1.5 million active military personnel—two-thirds more than Russia’s 900,000.25 The European Union, even without the United Kingdom, has a population triple Russia’s. As MIT’s Barry Posen has noted, “any inability on the part of European members of NATO to muster the military wherewithal to oppose Russian aggression involves more than a mere incapacity to allocate sufficient national resources to the challenge. It would be a defense-management failure of truly heroic proportions.”26

Technological shifts that give a larger advantage to the defensive side in land warfare underscore Posen’s conclusion.27 With the end of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty, wealthy and heavily industrialized European nations are well-positioned to turn to missiles, drones, and other standoff technology to augment their defenses against Russian offensive military power. The United States should also encourage greater cooperation among European nations to reduce dependence on U.S. logistics and intelligence support—rather than suppressing European defense autonomy in order to maintain U.S. dominance over its oldest allies.

Irregular warfare trends point in the same direction. Even in NATO’s extremely vulnerable Baltic salient, drones, improvised explosive devices, cell phones, and other commercial, off-the-shelf technology promise to make life difficult for an invader or occupier.28 As a defensive alliance, NATO’s hand is even stronger than the topline numbers suggest.

Given Europe’s ability to outgun Russia and thus maintain the traditional U.S. goal of preventing one power from controlling Eurasia, the United States can safely do less in Europe and save considerable sums. The United States currently accounts for more than 70 percent of total NATO defense spending.29 Americans should not be subsidizing Europe’s defense against a Russia whose population and economy are both far smaller, even when using purchasing power parity accounting. The implications are clear: Europe can and should defend itself against Russia with minimal U.S. support, at most a tripwire force and the promise of being under the U.S. nuclear umbrella.

Despite some provocative language earlier this year—like calling Vladimir Putin “a killer”—President Biden and his administration seem to be taking a pragmatic approach to Russia, which means not letting tension over human rights and Ukraine distract from making progress on other issues.30 An effort to shift the burden of European defense to European militaries could contribute to that effort, reduce incentives for Russia and China to more closely align, and allow the U.S. to focus more on China.

Tensions with China are rising just as fast, regardless of the wisdom of a “Cold War 2.0” construct. The solution to this heightened competition is not to summon European frigates to the South China Sea, dragging already free-riding allies into a new competition they prefer to avoid.31 Instead, Europe should carry the burden of its own continental security needs.

Minimize the Middle East

- The United States has limited vital interests in the Persian Gulf and the Middle East more broadly; the U.S. military posture in the region should reflect this.

- U.S. military missions in Iraq and Syria should be ended in an orderly fashion. U.S. forces in the Middle East should be withdrawn, with only a few exceptions.

- The Strait of Hormuz remains a key chokepoint for global oil and gas flows, but the U.S. Navy can control it from the outside in. The U.S. Fifth Fleet should be moved from Bahrain to a smaller base in Oman.

The first-order question in the Middle East is what vital interests require a U.S. military presence. The traditional trinity has been oil, Israel, and counterterrorism. But as scholars and policy experts have argued with increasing vigor, none of these issues have the salience they once did.32 None of these interests demands much in the way of a permanent U.S. regional military presence.

In a resource-constrained era of great power competition, avoiding distractions and resource drains is imperative. Forty years after the Carter Doctrine was promulgated, the Middle East is now rightly seen as a tertiary security concern of the United States. After two decades of intractable, Sisyphean wars in the greater Middle East, Americans also have little stomach for the continued expenditure of blood and treasure in the region. When Iranian drones and missiles struck Saudi Arabia’s Abqaiq and Khurais oil refineries in September 2019, causing an enormous initial disruption to global oil supplies, one poll showed that just 13 percent of Americans were in favor of the U.S. retaliating on behalf of Saudi Arabia.33

A 20-year counterterrorism campaign is used to justify the continued deployment of combat troops to Iraq and Syria. In reality, these troops are also employed as a hedge against Iranian influence.34 Yet these small military footprints (about 900 troops in Syria and 2,500 in Iraq) make U.S. troops more like hostages than assets.35 As we have seen repeatedly over the past four years, Iranian proxies can dial up the pressure at will by using rockets to threaten American troops and contractors at the handful of remaining big bases that house them. Tit-for-tat retaliatory strikes may be small scale and wholly symbolic, but they nonetheless risk drawing the United States and Iran into an unnecessary conflict that could be hugely destabilizing for the region.

This is to say nothing of the very real possibility of accidents or brinksmanship putting U.S. troops into a clash with a more substantial power than Iran, namely Russia in Syria. U.S. and Russian forces in Syria have successfully deconflicted to date, but past incidents have included a full-blown battle in which hundreds of Russian mercenaries were killed by U.S. fires.36 There is no guarantee of similar good judgement in the future.

Though the United States is not truly energy independent, the shale revolution has provided America with far more proven oil reserves and energy security (albeit with a high breakeven price). Most Middle East oil now goes to Asia; more than three-quarters of the oil transiting the Strait of Hormuz in 2018 went east. China draws nearly 40 percent of its imported oil from the Middle East, nearly triple as many barrels per day as the United States.37 (The percentages for U.S. allies Japan and South Korea are even higher).

Though China was the world’s fifth-largest oil producer in 2020, it consumes about three times as much oil as it produces.38 China’s oil vulnerability should be a factor in the U.S. military posture in the Middle East—but it does not require U.S. forces in the Persian Gulf or regular patrols to safeguard oil sea lanes. On the contrary: America’s most important Middle East oil security mission is being able to interdict oil flows to China in the event of war.

U.S. military presence in the Middle East

The U.S. military maintains an outsized basing presence for ground troops in the Middle East, despite the region’s marginal and shrinking strategic importance.

The U.S. economy is also far better insulated from oil price shocks than it was during the 1970s OPEC embargo.39 In five of the six major oil shocks since 1978, the price of oil recovered in three months or less.40 And unlike in the 1970s, there is no power with the ability to control the Persian Gulf’s reserves: sanctions-wracked Iran is a poor substitute for the USSR.

Israel, the region’s pre-eminent military power, is able to take care of itself. With the only nuclear arsenal in the Middle East (and a secure second-strike capability), conventional forces that have repeatedly trounced all of its neighbors, and cutting-edge missile defense, cyber, and drone technology, Israel is more militarily secure than it has ever been. Its shadow war with Iran has only underscored this reality, as Israel has repeatedly struck Iran-linked targets in Syria and penetrated Iran for sabotage missions and high-level assassinations, including the killing of Iran’s top nuclear scientist, Mohsen Fakhrizadeh.

After the failed war in Iraq, the United States grew less enthusiastic about regional transformation and counterinsurgency. Though U.S. partners in the region provide valuable intelligence sharing and counterterrorism coordination, these ends do not require a significant troop presence. Relationships are best sustained by the regular intelligence and security cooperation coordinated from U.S. embassies, supplemented by drone strikes or over-the-horizon special operations raids on those rare terrorist targets that have both the intent and the capability to attack the United States.

There is also a larger problem with the logic underpinning America’s Middle East security posture. The belief that a robust U.S. military presence in the region, with forward deployed American troops, promotes order and stability is an article of faith to many in Washington. The history of U.S. military operations in the Middle East suggests foreign forces are more often a source of instability—a motivator of violent resistance—than a source of order.41 There are now roughly four times as many Sunni Islamic militants as there were 20 years ago on 9/11.42

Moreover, the region’s future demographic, economic, and climate challenges argue against any security-focused solution. Both demographic and climate change are being aptly described as “force multipliers” for the Middle East’s existing social and political instability.43 Birth rates and slow growth suggest the region’s high youth unemployment is likely to worsen, creating a large cadre of young men available for extremist and insurgent groups.44 Climate change, by diminishing farmland, water resources, and potentially displacing large numbers of people, will probably exacerbate instability.45 The challenges of stabilizing the region with U.S. military forces—already insurmountable—will become even more difficult.

President Biden’s decision to unequivocally withdraw all U.S. troops from Afghanistan was a strong first step in recognizing the limits of U.S. military power in the greater Middle East. The recent withdrawal of eight Patriot missile defense batteries and one Terminal High-Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) battery, primarily from Saudi Arabia, rightly prioritized the reallocation of key military assets.46

Further drawdowns are warranted, particularly in the Persian Gulf. The vulnerability of U.S. aircraft carriers and naval vessels in the narrow Gulf has been clear since at least the 2002 Millennium Challenge exercise.47 The utility of basing the Fifth Fleet at Bahrain thus deserves special scrutiny. With more than two-thirds of Persian Gulf oil now going to Asia, where it feeds both China and U.S. allies, the ability to control the Strait of Hormuz remains a powerful strategic lever. However, U.S. naval and air forces can best control the Strait from the outside in, via a naval base on Omani territory—perhaps as a neighbor to the United Kingdom’s new Joint Logistics Support Base in Duqm.48 U.S. forces in Bahrain are vulnerable to Iranian missiles and proxy forces. The Fifth Fleet can better and more safely conduct its mission from a naval base several hundred miles farther south.

Cut missions to improve readiness

- Despite the absence of a major conflict, the U.S. continues to burn up readiness through unsustainable operational tempo, largely in the Middle East. The U.S. Navy’s aircraft carriers, in particular, should immediately return to a sustainable deployment cycle.

- The force is large enough—DoD should learn to say “no” to the endless requests for forces from the geographic combatant commanders.

- The current deployment rate erodes the health of the force and works to the detriment of U.S. power in the long term.

The U.S. military is conducting operations all over the world every day (a very small percentage of which are combat operations) but the nation is not at war in any meaningful sense. Military competition with China is likely to be an enduring challenge. The sustainability and preservation of U.S. military forces for this competition should be a key consideration in any evaluation of America’s global military posture and operational tempo.

For active-duty units, the DoD seeks a 1:3 deployment-to-dwell ratio, meaning a servicemember who spends six months overseas should have eighteen months at home before his or her next deployment. This allows time for family stability, the maintenance of physical and mental health, and the accomplishment of individual training and education (both military and civilian schooling). Deployment-to-dwell ratios do not account for the fact that many soldiers and units spend much of their stateside time away from their home station, whether on major exercises, at training courses, or fulfilling other obligations.

The U.S. Army considers a 1:2 deployment-to-dwell ratio to be a redline that risks the long-term health and sustainability of the force. Currently much of the Army is failing to meet this mark. Armor brigade combat teams (BCTs), combat aviation brigades (CABs), and Patriot missile defense batteries—collectively much of the Army’s “teeth”—are all short of a 1:2 deployment-to-dwell ratio.49 Corps headquarters are currently at less than a 1:1 deployment-to-dwell ratio.50

As bad as the Army’s operational tempo is, the U.S. Navy’s is worse. In 2014 the Navy rolled out its Optimized Fleet Response Plan, mandating 36-month cycles for ships and their crews, of which 8 months would be spent deployed. Yet the Navy has failed to meet its own milestones. This became tragically clear in 2017, when overworked sailors were judged to be a key factor in a pair of Pacific collisions between Navy ships and civilian vessels that left 17 sailors dead.51 Despite these disasters, the problem has not been solved.

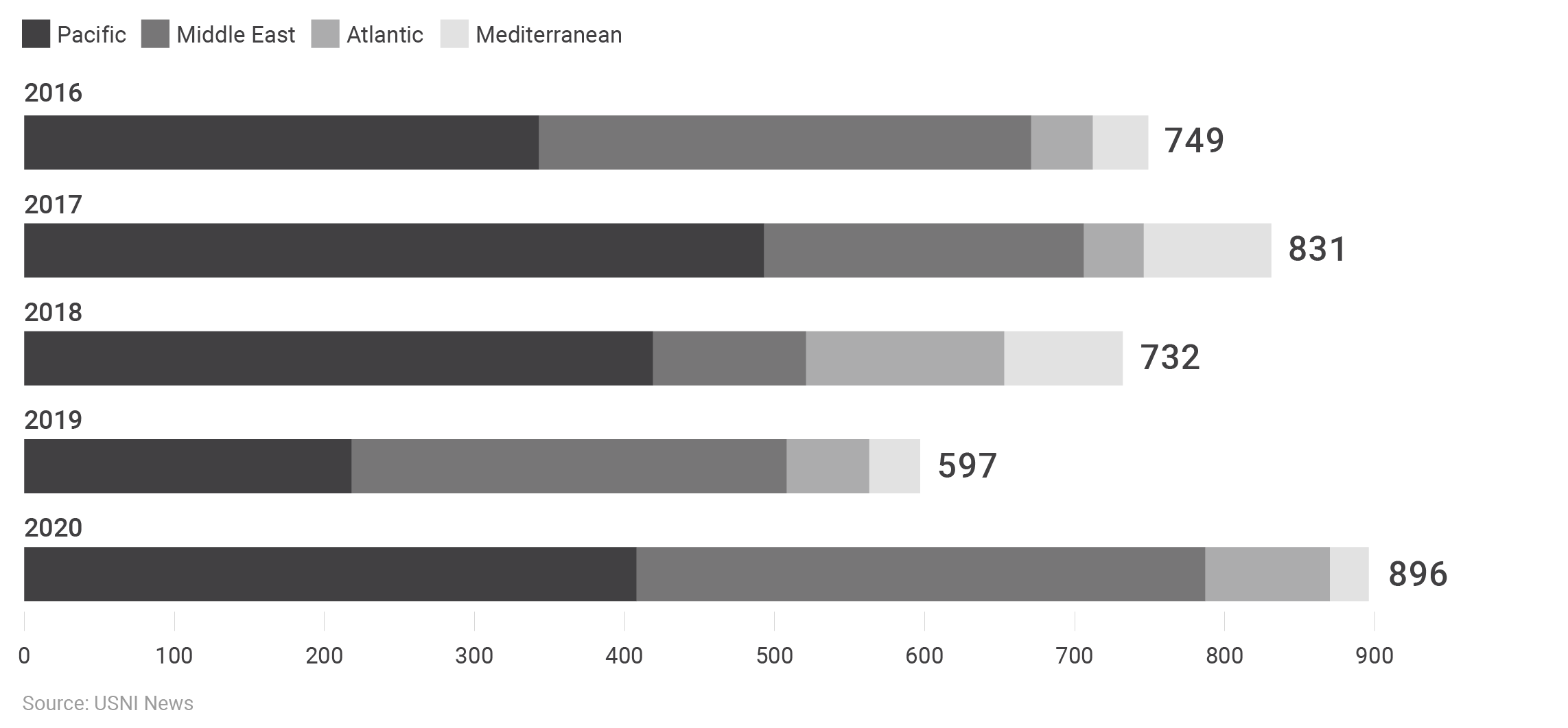

Operational tempo is highest in the Navy’s crown jewels, its nuclear supercarriers. Last year was the busiest for the carrier fleet since the Arab Spring nearly a decade ago.52 Several carriers were tasked to “double pump,” to conduct back-to-back deployments without a major maintenance period in between. As the U.S. Naval Institute’s Megan Eckstein reported in November, “Today, the Pentagon is using up aircraft carrier readiness faster than the Navy can generate it.”53

The Middle East has been the primary culprit. The U.S. Naval Institute found that the Middle East drew almost as much carrier presence as the entire Pacific in 2020.54 This is despite evidence that U.S. adversaries, such as Iran, seem increasingly unfazed by the presence of aircraft carriers in their neighborhoods.1 The United States now faces the temporary absence of a carrier from the entire Pacific, as the USS Ronald Reagan, homeported in Japan, covers the Afghanistan withdrawal this summer.56

History suggests that overworking Navy ships and crews eventually yields a steep bill in both personnel and materiel. Retention will suffer as good sailors leave the Navy after too much time away from their families. The maintenance toll will also be substantial. When the USS Dwight D. Eisenhower (CVN 69) did two sets of double pumps a few years ago, its subsequent 14-month maintenance period ballooned to 23 months because of the wear and tear that had been inflicted on the ship.57

Total carrier days deployed per year

Due mostly to overstretch from continuing missions in the Middle East and new missions in the Indo-Pacific, U.S. Navy carrier operations reached a recent high in 2020.

The situation is better in the special operations community, at least compared to its recent past. Former Assistant Secretary of Defense for Special Operations and Low Intensity Conflict (ASD/SOLIC) Owen West testified before the Senate in February 2019 that 90 percent of special operations forces (SOF) were meeting their desired dwell time—a 1:2 deployment-to-dwell ratio.58 Gen. Richard Clarke, commander of U.S. Special Operations Command, testified in March that there are currently fewer special operators deployed overseas than at any time since the 2001 terrorist attacks.59

However, it was just three years ago that inadequate dwell time was blamed for training shortfalls that contributed to the deaths of four U.S. Army Special Forces personnel after a firefight in Niger on October 4, 2017.60 Increasing ethical and behavior problems in the SOF community, especially among Naval Special Warfare operators, may also be due to years of unsustainable operational tempo.61

In response to the purported demands of the present and the future, some argue that the United States should grow the force, as was done at the height of the post-9/11 wars.62 But manpower is expensive; pay and benefits for military and civilian employees is the single largest item in the Pentagon’s budget.63 In making the U.S. military’s modern marathon sustainable, the correct course is not to grow the force but to put the geographic combatant commands on a diet and dramatically reduce unnecessary overseas deployments and presence missions. The overworked carrier fleet is the best place to start.

What a successful Global Posture Review would look like

The 2021 Global Posture Review has the chance to be a meaningful strategic document, reordering the U.S. military footprint for great power competition abroad and reinvestment and renewal at home, as the Biden administration’s national security principals have repeatedly promised.64 For decades now, the U.S. global security posture has been predicated on the leftover assumptions of the Cold War and the War on Terror. These legacy deployments are even less sustainable than the legacy weapons systems that conduct them.65

America’s diminishing military and economic primacy demands a revision of outmoded commitments, deleterious deployments, and obsolete strategic thinking. Through balancing and burden sharing in Asia, major troop reductions in Europe and the Middle East, and limiting presence deployments to preserve military readiness, the United States can reset itself for both renewal at home and enduring competition with China.

Endnotes

1 “Remarks by President Biden on America’s Place in the World,” White House, February 4, 2021, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/speeches-remarks/2021/02/04/remarks-by-president-biden-on-americas-place-in-the-world.

2 Jon D. Klaus, “U.S. Military Overseas Basing: Background and Oversight Issues for Congress,” Congressional Research Service (RS21975), November 17, 2004, https://www.everycrsreport.com/files/20041117_RS21975_07d98b917769a1d334b626796485a5c699a47fd8.pdf.

3 George Petras, Karina Zaiets, and Veronica Bravo, “Exclusive: U.S. Counterterrorism Operations Touched 85 Countries in the Last 3 years Alone,” USA Today, updated February 26, 2021, https://www.usatoday.com/in-depth/news/2021/02/25/post-9-11-us-military-efforts-touched-85-nations-last-3-years/6564981002.

4 George Petras, Karina Zaiets, and Veronica Bravo, “Exclusive: U.S. Counterterrorism Operations Touched 85 Countries in the Last 3 years Alone.”

5 Asma Khalid and Barbara Sprunt, “Biden Counters Trump’s ‘America First’ With ‘Build Back Better’ Economic Plan,” NPR, July 9, 2020, https://www.npr.org/2020/07/09/889347429/biden-counters-trumps-america-first-with-build-back-better-economic-plan; Frank Hoffman, “U.S. Defense Strategy After the Pandemic,” War on the Rocks, April 20, 2021, https://warontherocks.com/2021/04/u-s-defense-strategy-after-the-pandemic.

6 “Interim National Security Strategic Guidance,” White House, March 2021, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/NSC-1v2.pdf.

7 Thomas Shugart, “First Strike: China’s Missile Threat to U.S. Bases in Asia,” Center for a New American Security, June 28, 2017, https://www.cnas.org/publications/reports/first-strike-chinas-missile-threat-to-u-s-bases-to-asia; Otto Kreisher, “China’s Carrier Killer: Threats and Theatrics,” Air Force Magazine, December 2013, https://www.airforcemag.com/PDF/MagazineArchive/Documents/2013/December%202013/1213china.pdf.

8 “Pentagon Issues Directive on Countering China, But Offers Few Details,” Reuters, June 9, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/world/us/pentagon-issues-directive-countering-china-offers-few-details-2021-06-09.

9 Thomas Shugart, “First Strike: China’s Missile Threat to U.S. Bases in Asia.”

10 Jack Detsch, “Pentagon Faces Tense Fight Over Pacific Pivot,” Foreign Policy, June 7, 2021, https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/06/07/biden-pivot-china-pentagon.

11 Tanner Greer, “American Bases in Japan Are Sitting Ducks,” Foreign Policy, September 4, 2019, https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/09/04/american-bases-in-japan-are-sitting-ducks.

12 Megan Eckstein, “Berger: Marines Focused on China in Developing New Way to Fight in the Pacific,” USNI News, October 2, 2019, https://news.usni.org/2019/10/02/berger-marines-focused-on-china-in-developing-new-way-to-fight-in-the-pacific.

13 Mark Cancian, “The Marine Corps’ Radical Shift Toward China,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, March 25, 2020, https://www.csis.org/analysis/marine-corps-radical-shift-toward-china.

14 Thomas Shugart, “First Strike: China’s Missile Threat to U.S. Bases in Asia.”

15 Richard Haas and David Sacks, “American Support for Taiwan Must Be Unambiguous,” Foreign Affairs, September 2, 2020, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/american-support-taiwan-must-be-unambiguous.

16 Elbridge Colby and Jim Mitre, “Why the Pentagon Should Focus on Taiwan,” War on the Rocks, October 7, 2020, https://warontherocks.com/2020/10/why-the-pentagon-should-focus-on-taiwan.

17 Paul Huang, “Taiwan’s Military Is a Hollow Shell,” Foreign Policy, February 15, 2020, https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/02/15/china-threat-invasion-conscription-taiwans-military-is-a-hollow-shell.

18 Tanner Greer, “Taiwan Can Win a War With China,” Foreign Policy, September 25, 2018, https://foreignpolicy.com/2018/09/25/taiwan-can-win-a-war-with-china.

19 Eugene Gholz, Benjamin Friedman, and Enea Gjoza, “Defensive Defense: A Better Way to Protect U.S. Allies in Asia,” Washington Quarterly 42:4 (2019), 171–189, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/0163660X.2019.1693103.

20 “An Alliance’s Four Quadrants,” U.S. Naval Institute Blog, March 17, 2021, https://blog.usni.org/posts/2021/03/17/an-alliances-four-quadrants.

21 Andrew Chuter, “Who Are the Winners and Losers in Britain’s New Defense Review?” Defense News, March 22, 2021, https://www.defensenews.com/global/europe/2021/03/22/who-are-the-winners-and-losers-in-britains-new-defense-review.

22 Madison Creery, “The Russian Edge in Electronic Warfare,” Georgetown Security Studies Review, June 26, 2019, https://georgetownsecuritystudiesreview.org/2019/06/26/the-russian-edge-in-electronic-warfare.

23 “Russia: An Assumptions Check, moderated by Andrea Kendall-Taylor, featuring Eddie Fishman, Michael Kofman, and Margarita Konaev,” Center for a New American Security, June 11, 2021, https://conference.cnas.org/session/russia-an-assumptions-check.

24 Richard Connolly, “Russian Military Expenditure in Comparative Perspective: A Purchasing Power Parity Estimate,” CNA, October 9, 2019, https://www.cna.org/CNA_files/PDF/IOP-2019-U-021955-Final.pdf.

25 “Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2013–2019),” NATO, November 29, 2019, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/news_171356.htm; “The Military Balance 2020,” International Institute for Strategic Studies (Abingdon: Routledge, 2020): 194.

26 Barry R. Posen, “Europe Can Defend Itself,” Survival 62:6 (December 2, 2020), 9, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00396338.2020.1851080.

27 Robert Scales, “Return to Gettysburg: The Fifth Epochal Shift in the Couse of War,” War on the Rocks, October 1, 2018, https://warontherocks.com/2018/10/return-to-gettysburg-the-fifth-epochal-shift-in-the-course-of-war.

28 T. X. Hammes, “The Melians’ Revenge,” Atlantic Council, June 27, 2019, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/issue-brief/the-melians-revenge-how-small-frontline-european-states-can-employ-emerging-technology-to-defend-against-russia.

29 Lucie Béraud-Sudreau and Nick Childs, “The U.S. and its NATO Allies: Costs and Value,” IISS Military Balance Blog, July 9, 2018, https://www.iiss.org/blogs/military-balance/2018/07/us-and-nato-allies-costs-and-value.

30 Anton Troianovski, “Russia Erupts in Fury Over Biden’s Calling Putin a Killer,” New York Times, March 18, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/18/world/europe/russia-biden-putin-killer.html; Vladimir Soldatkin and Steve Holland, “Far Apart at First Summit, Biden and Putin Agree to Steps on Cybersecurity, Arms Control,” Reuters, June 26, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/world/wide-disagreements-low-expectations-biden-putin-meet-2021-06-15.

31 Masaya Kato, “European Navies Build Indo-Pacific Presence as China Concerns Mount,” Nikkei Asia, March 4, 2021, https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/International-relations/Indo-Pacific/European-navies-build-Indo-Pacific-presence-as-China-concerns-mount.

32 Justin Logan, “The Case for Withdrawing from the Middle East,” Defense Priorities, September 2020, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/the-case-for-withdrawing-from-the-middle-east.

33 John Haltiwanger, “Just 13% of Americans Would Support U.S. Military Going to War Over Saudi Oil Field Attack,” Business Insider, September 18, 2019, https://www.businessinsider.com/13-percent-americans-support-us-military-response-saudi-oil-attack-2019-9.

34 Jacob Magid, “Ex-Syria Envoy Felt Trump Was Unqualified. Now He’s Sad to See Administration Go,” Times of Israel, December 5, 2020, https://www.timesofisrael.com/ex-syria-envoy-felt-trump-was-unqualified-now-hes-sad-to-see-administration-go.

35 David Cloud, “Inside U.S. Troops’ Stronghold in Syria, a Question of How Long Biden Will Keep Them There,” Los Angeles Times, March 12, 2021, https://www.latimes.com/politics/story/2021-03-12/us-troops-syria-civil-war-biden.

36 Thomas Gibbons-Neff, “How a 4-Hour Battle Between Russian Mercenaries and U.S. Commandos Unfolded in Syria,” New York Times, May 24, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/24/world/middleeast/american-commandos-russian-mercenaries-syria.html.

37 “Factbox: Asia Region Is Most Dependent on Middle East Crude Oil, LNG Supplies,” Reuters, January 8, 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/asia-mideast-oil-factbox/factbox-asia-region-is-most-dependent-on-middle-east-crude-oil-lng-supplies-idINKBN1Z71VW.

38 “What countries are the top producers and consumers of oil?” U.S. Energy Information Administration, accessed June 25, 2021, https://www.eia.gov/tools/faqs/faq.php?id=709&t=6.

39 Olivier J. Blanchard and Jordi Galí, “The Macroeconomic Effects of Oil Price Shocks: Why Are the 2000s So Different from the 1970s?” in Jordi Galí and Mark J. Gertler, eds., International Dimensions of Monetary Policy (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009), 373–421.

40 Justin Logan, “The Case for Withdrawing from the Middle East.”

41 Emma Ashford, “Unbalanced: Rethinking America’s Commitment to the Middle East,” Strategic Studies Quarterly vol. 12, no. 1 (2018), 127–48.

42 Seth Jones, “The Evolution of the Salafi-Jihadist Threat,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, November 20, 2018, https://www.csis.org/analysis/evolution-salafi-jihadist-threat

43 “The Impact of Climate Change on the Middle East,” Middle East Policy Council, April 23, 2021, https://mepc.org/hill-forums/impact-climate-change-middle-east.

44 Nader Kabbani, “Youth Employment in the Middle East and North Africa: Revisiting and Reframing the Challenge,” Brookings Institution, February 26, 2019, https://www.brookings.edu/research/youth-employment-in-the-middle-east-and-north-africa-revisiting-and-reframing-the-challenge.

45 Sagatom Saha, “How Climate Change Could Exacerbate Conflict in the Middle East,” Atlantic Council, May 14, 2019, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/menasource/how-climate-change-could-exacerbate-conflict-in-the-middle-east.

46 Gordon Lubold, Nancy Youssef, and Michael Gordon, “U.S. Military to Withdraw Hundreds of Troops, Aircraft, Antimissile Batteries from Middle East,” Wall Street Journal, June 18, 2021, https://www.wsj.com/articles/u-s-military-to-withdraw-hundreds-of-troops-aircraft-antimissile-batteries-from-middle-east-11624045575.

47 Micah Zenko, “Millennium Challenge: The Real Story of a Corrupted Military Exercise and Its Legacy,” War on the Rocks, November 5, 2015, https://warontherocks.com/2015/11/millennium-challenge-the-real-story-of-a-corrupted-military-exercise-and-its-legacy.

48 Mike Sweeney, “A Plan for U.S. Withdrawal from the Middle East,” Defense Priorities, December 2020, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/a-plan-for-us-withdrawal-from-the-middle-east.

49 Bradley Bowman, “Why We Should Grow the Active Duty Army,” RealClear Defense, February 14, 2020, https://www.realcleardefense.com/articles/2020/02/14/why_we_should_grow_the_active_duty_army_115042.html.

50 Bradley Bowman, “Why We Should Grow the Active Duty Army.”

51 Sam LaGrone, “NTSB: Lack of Navy Oversight, Training Were Primary Causes of Fatal McCain Collision,” USNI News, August 6, 2019, https://news.usni.org/2019/08/06/ntsb-lack-of-navy-oversight-training-were-primary-causes-of-fatal-mccain-collision.

52 Megan Eckstein, “No Margin Left: Overworked Carrier Force Struggles to Maintain Deployments After Decades of Overuse,” USNI News, November 12, 2020, https://news.usni.org/2020/11/12/no-margin-left-overworked-carrier-force-struggles-to-maintain-deployments-after-decades-of-overuse.

53 Megan Eckstein, “No Margin Left: Overworked Carrier Force Struggles to Maintain Deployments After Decades of Overuse.”

54 Sam LaGrone, “Japan-based Carrier USS Ronald Reagan Will Make Rare Middle East Patrol to Cover Afghanistan Withdrawal,” USNI News, May 26, 2021, https://news.usni.org/2021/05/26/japan-based-carrier-uss-ronald-reagan-will-make-rare-patrol-to-middle-east-to-cover-afghanistan-withdrawal.

55 Kathryn Wheelbarger and Dustin Walker, “Iran Isn’t Afraid of B-52s and Aircraft Carriers,” Wall Street Journal, December 21, 20202, https://www.wsj.com/articles/iran-isnt-afraid-of-b-52s-and-aircraft-carriers-11608593380.

56 Nancy Youssef and Gordon Lubold, “Sole U.S. Aircraft Carrier in Asia-Pacific to Help With Afghanistan Troop Withdrawal,” Wall Street Journal, May 26, 2021, https://www.wsj.com/articles/u-s-aircraft-carrier-leaving-asia-to-help-with-afghanistan-troop-withdrawal-11622034089.

57 Megan Eckstein, “No Margin Left: Overworked Carrier Force Struggles to Maintain Deployments After Decades of Overuse.”

58 “United States Special Operations Command and United States Cyber Command,” U.S. Senate Committee on Armed Services, February 14, 2019, https://www.armed-services.senate.gov/hearings/19-02-14-united-states-special-operations-command-and-united-states-cyber-command.

59 Corey Dickstein, “Fewest Number of Special Ops Forces Deployed Since 2001 as Pentagon Reviews Decisions to Draw Down Troops,” Stars and Stripes, March 25, 2021, https://www.stripes.com/news/us/fewest-number-of-special-ops-forces-deployed-since-2001-as-pentagon-reviews-decisions-to-draw-down-troops-1.667292.

60 “Terrorist Ambush in Niger,” U.S. Department of Defense, accessed June 25, 2021, https://dod.defense.gov/news/special-reports/niger.

61 Margaux Hoar and Jonathan Schroden, “Do the SEALs Have a Culture Problem or an OPTEMPO Problem? The Answer Might be ‘Yes,’” CNA, August 12, 2019, https://www.cna.org/news/InDepth/article?ID=8.

62 Kyle Rempfer, “The Force Is Still Too Small, Army Chief Says, and Afghanistan Withdrawal Won’t Really Help,” Army Times, April 27, 2021, https://www.armytimes.com/news/your-army/2021/04/27/the-force-is-still-too-small-army-chief-says-and-afghanistan-withdrawal-wont-really-help.

63 Katherine Blakeley, “Military Personnel,” Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, August 15, 2017, https://csbaonline.org/reports/military-personnel.

64 Salman Ahmed, Wendy Cutler, Rozlyn Engel, David Gordon, Jennifer Harris, Douglas Lute, Daniel Price, Christopher Smart, Jake Sullivan, Ashley Tellis, and Tom Wyler, “Making U.S. Foreign Policy Work Better for the Middle Class,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, September 23, 2020, https://carnegieendowment.org/2020/09/23/making-u.s.-foreign-policy-work-better-for-middle-class-pub-82728.

65 Megan Eckstein, “Navy ‘Struggling’ to Modernize Aging Cruiser Fleet As Tight Budgets Push Pentagon to Shed Legacy Platforms,” USNI News, April 5, 2021, https://news.usni.org/2021/04/05/navy-struggling-to-modernize-aging-cruiser-fleet-as-tight-budgets-push-pentagon-to-shed-legacy-platforms.