Counting the cost of financial warfare

Recalibrating sanctions policy to preserve U.S. financial hegemony

Enea Gjoza

November 11, 2019

Key points

The American economy, dollar, and banking system create unparalleled power for the U.S. in the global financial system. This power provides disproportionate influence over the world’s key economic and financial institutions, regulatory authority over major foreign companies and banks, and allows borrowing on favorable terms and in dollars, enabling long-term deficit spending.

U.S. policymakers are increasingly deploying financial sanctions to punish or coerce other states. Once targeted at weak rogue states, sanctions are now used against great powers and allies.

These sanctions yield few political victories because they ask too much and are often implemented reflexively, to punish, rather than strategically, to achieve a desired outcome. But they carry serious political and economic costs—damaging relations with allies and locking American companies out of foreign markets.

The overuse of financial sanctions has spurred Russia, China, and now the EU to work on alternative institutions that would place their companies outside the reach of the U.S.

While this parallel infrastructure is still in the early stages, it could threaten U.S. financial dominance and the status of the dollar if it succeeds—balkanizing the global financial system into different spheres of influence.

The U.S. need not forswear sanctions altogether but should dial them back. Sanctions should be deployed against adversaries rather than allies or partners—rarely and strategically against great powers—in pursuit of clear, attainable goals, and continually re-evaluated for effectiveness.

With no perceived threat, other countries will likely abandon their alternative institutions, which are expensive and worthwhile only so long as U.S. action makes the current system unreliable.

OVERVIEW

Dominance in global finance benefits the U.S. in several ways. The U.S. government disproportionately shapes the rules and norms governing global economic activity, can borrow on favorable terms and in its own currency—allowing it to run up massive, consistent deficits with little penalty—and can influence foreign firms and nations in pursuit of its foreign policy goals.

In recent decades, the U.S. has liberally leveraged this position to pressure foreign governments, including European allies, in the hopes of changing their political behavior.1 The results of this effort have largely been unsatisfactory, yielding little in the way of political gains while inflicting costs on the U.S. economy and degrading the foundation of U.S. financial power.

Access to the American financial system and U.S. dollars (USD) is essential for global transactions. By implementing financial sanctions—locking other nations out of its system until they submit to political demands—the U.S. has a powerful tool to extract political concessions. Overusing this tool motivates other states to develop alternatives to U.S.-dominated institutions, however, which erodes U.S. financial hegemony—and might eventually end it.

Although financial sanctions have come into vogue among policymakers as a seemingly low-cost, effective way to manage hostile states, other nations are increasingly alarmed at the weaponization of commercial institutions. Financial coercion has made both allies and adversaries aware of just how vulnerable they are to U.S. pressure. This realization has spurred other major economies to invest in alternatives to the current U.S.-led system.

Aside from carrying long-term costs for U.S. dominance, the efficacy of liberally applied sanctions deserves further scrutiny. Sanctions often succeed in punishing adversaries but this tactical achievement rarely reforms target states’ behavior when important policies are at stake.1 Sanctions do shift commercial activity to channels outside the reach of the U.S., however, and change the cost benefit calculus for affected nations, making them more likely to invest in building their own alternative institutions to bypass the American-led system.

The U.S. should not renounce sanctions as a policy tool but should use them far more judiciously. In many cases, policymakers have reacted to the failure of sanctions to change a target’s behavior with even more sanctions, locking in hostile relationships and locking American firms and those of U.S. allies out of the sanctioned economy. This means forgone opportunities for wealth creation in the U.S. and a market opening for competitors, often from great power rivals like China and Russia.

There are currently 20 country-based or country-related sanctions programs

Foreign governments and companies aren’t bound to use the U.S.-led system—they do so because it’s the most attractive among existing alternatives. As that appeal wanes through increased financial and economic weaponization, they will inevitably seek out other avenues to conduct business.

Many of these alternatives are still in their infancy but as they grow, they will diminish the U.S.’s dominance of the global financial system. Should they become fully viable competitors to the U.S.-led order, they will undermine a key pillar of American power. The U.S. gains many economic benefits from its role as the world’s financial hub, as this paper will demonstrate. The ultimate cost of losing financial hegemony will far outweigh the often-modest gains the U.S. secures by weaponizing its dominance.

UNDERPINNING THE GLOBAL ECONOMY AND THE U.S. DOLLAR

The U.S. emerged from World War II as a superpower, the preeminent capitalist nation, and was in the enviable position of being able to shape the institutions that would govern the world economy. In the 1944 Bretton Woods conference, the U.S., along with 43 other nations, established the so called “twin pillars” of the global economic and financial system: the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), later to become part of the World Bank; and the International Monetary Fund (IMF).3

The IBRD was created to promote economic development and rebuild nations devastated by the war, while the IMF was designed to provide short-term financing to nations facing financial crises and maintain “a system of fixed exchange rates centered on the U.S. dollar and gold.”4 By the end of WWII, the U.S. held 75 percent of the world’s monetary gold reserves and was the only nation with a currency still pegged to gold, making it the only viable candidate to be the lynchpin of this system.5 An informal agreement among the allies meant that the head of the World Bank would always be an American, and the head of the IMF would always be a European.6 The Soviet Union, while present at Bretton Woods, never ratified the treaty and did not participate in these institutions until its successor states joined following the Soviet collapse.7

The system of fixed exchange rates that emerged from Bretton Woods lasted until 1971, when President Nixon ended the international convertibility of USD to gold.8 By 1973, the world had transitioned into a system of floating exchange rates and fiat money—meaning currencies backed by government decree and the wealth of each country, rather than explicitly supported by precious metals. Despite this transition, given that America was still the preeminent political and economic powerhouse, the USD supplanted gold to become the world’s only reserve currency.

The dollar being the world’s reserve currency means that other countries are willing to hold USD they receive and not demand American goods or their own currencies in return. Their monetary authorities build up USD “reserves,” which they use to back the value of their money. In the developed world, countries do not need to hold dollars to back their currencies. But because almost everyone has USD, the dollar is used for much more than simply backing the value of foreign currencies.

Currencies serve several functions:9

Medium of exchange—a means of facilitating trade;

Store of value—a mechanism of preserving existing wealth;

- Unit of account—the currency in which many goods and services are priced; and

- Standard of deferred payment—the means of pricing bonds and other debt.

In the decades after WWII, USD gradually became the predominant mechanism for fulfilling all these functions. Most global trade was and is conducted in USD. Even trade done by eurozone countries with non-eurozone countries is largely conducted in USD.

Furthermore, a key global commodity—oil—is also mostly priced in USD, forcing those who wish to buy and sell it to use the dollar. No longer backed by gold after 1971, the USD was instead supported by a deal cut in 1974 with Saudi Arabia and other Middle Eastern oil producers. In exchange for U.S. political and military support, major oil producers agreed to only accept USD for oil and reinvest some of their profits into U.S. Treasury bonds (reserves to back their own currencies).10 This arrangement stimulated massive international demand for “petrodollars,” as countries needed to acquire USD and dollar assets to purchase oil, which in turn helped finance U.S. deficit spending.11

As global trade was dominated by the dollar, so went the global financial system. While the world was transitioning into a floating exchange rate regime in 1973, a consortium of 239 banks from 15 countries launched the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT).12 Headquartered in Belgium, SWIFT’s purpose was to standardize inter-bank communications globally, allowing banks to communicate (and thus transact) across borders despite differences in language and systems. Over the years, membership in the consortium has become essential for banks to operate internationally. As a result, SWIFT has grown to 11,000 member institutions, representing nearly every country.

Because the world needs USD, and because the dollar runs through American banks and ultimately the Federal Reserve, the U.S. also has incredible control over foreign banks who need USD, their clients who need to transact in USD, and institutions such as SWIFT. The dollar overwhelmingly dominates the foreign exchange markets, accounting for 87.6 percent of global market turnover in 2016.13 This means those looking to convert one third-party currency to another (say Chinese yuan to Pakistani rupees) will often have to convert their own currency to USD before buying the destination currency. The ability to limit access to USD thus creates a potent bottleneck even for those not trading with the U.S.

TOOLS IN THE TOOLBOX

Foreign regimes often behave in ways the U.S. finds distasteful, but given the high cost of military action, the U.S. government has sought ways to coerce or punish them short of war. By offering a means to exert pressure at a seemingly low cost (given the size and strength of the U.S. economy relative to many of its targets), sanctions have become a preferred policy tool for such ventures.

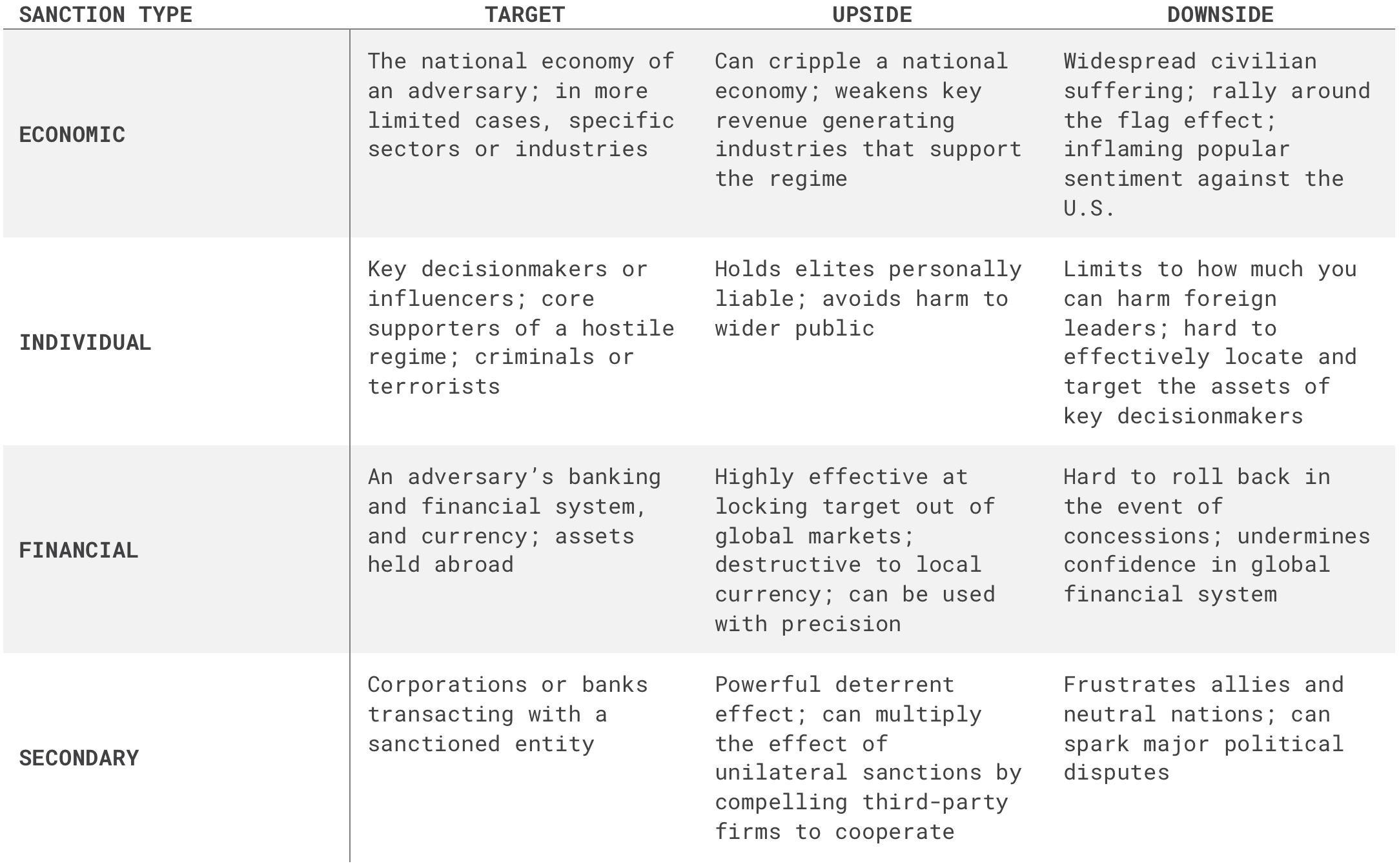

The U.S. has historically deployed several types of sanctions to achieve its foreign policy goals:

- Economic sanctions are designed to sever a target nation from its international trade relationships at either the industry or economy-wide level, drying up markets for its products and denying it crucial imports. They have been a longstanding and particularly popular tool for U.S. policymakers and have often been undertaken unilaterally, as in the case of Cuba, which has been under U.S. economic sanctions for decades.14

- Individual sanctions represent an attempt to avoid harming the adversary’s civilian population by personally punishing key elites. These sanctions were first introduced against Haitian military leaders in 1993 and have since grown to include visa bans, asset freezes, and blacklisting of the affected individual (and sometimes their family members) from conducting business with reputable financial institutions.15

- Financial sanctions are designed to block the target from transacting with the financial institutions and in the financial markets of the U.S. and its commercial partners. In practice, this severing from the dollar system can undermine the target nation’s banking industry, currency, and ability to process international payments. With the so-called War on Terror, the U.S. honed its ability to apply pressure on adversaries via the international financial system and has deployed such sanctions repeatedly against both state and non-state actors.16

- Secondary sanctions are used to sanction third-party economic actors that attempt to do business with sanctioned entities. While they are simply an enforcement mechanism for primary sanctions and often take the form of financial sanctions on banks or corporations that transact with a sanctioned entity, it is useful to treat them as distinct because they must inevitably target the firms of allied or neutral states, thus generating detrimental political consequences.

Cost-benefit analysis of various types of sanctions

DO SANCTIONS WORK?

Sanctions are a frequently-used tool because the domestic politics behind them are compelling. Imposing sanctions provides a political bump to policymakers who want to appear strong during international disputes without incurring domestic political risk.17 In these cases, whether the sanction works well or not as a policy tool is less important than its ability to be touted before domestic audiences. As long as sanctions remain on, policymakers can argue that the target entity is paying a price for its behavior, regardless of whether the sanction is actually advancing the desired foreign policy objective.

Scholars have extensively examined the effectiveness of sanctions; the research shows economic sanctions tend to be ineffective at changing state behavior, primarily because other self-interested nations will step in to fill the void where the U.S. or its allies have severed relations.18 For example, with U.S. and European firms locked out of Iran due to the Trump administration’s “maximum pressure” policy, Chinese companies have provided Iran with a lifeline, in the process establishing near monopolies for themselves in key sectors of the Iranian economy.19 In this way, sanctions can at times be strategically self-defeating.

Additionally, sanctions are often used to compel a costly political concession from an adversary—one that touches on a perceived national interest that the target government is willing to endure economic hardship to protect. Despite several rounds of U.S. sanctions designed to deter Pakistan from pursuing a nuclear weapon, Pakistan ultimately ignored outside pressure and acquired its own nuclear arsenal to defend against archrival India.20 Germany is proceeding with the construction of the Nord Stream 2 pipeline despite U.S. sanctions threats because of the importance of Russian natural gas to its economy.21 Similarly, Turkey demonstrated it is willing to accept mandatory U.S. sanctions in order to purchase the S-400 air defense system over U.S. objections.22

The most comprehensive sanctions ever imposed—on Iraq between 1990 and 2003—nearly halved its GDP but led to neither regime change nor major political concessions.23 In autocracies, which tend to be the primary targets, sanctions often help strengthen the ruling regime, allowing it to deny scarce resources to domestic opponents while lavishing them on a narrow group of supporters.24 Rather than weakening the regime in Tehran with its domestic public, “maximum pressure” actually helped Iran’s Revolutionary Guards sell a nationalist message to Iranians—convincing many to rally behind the regime against the perceived foreign adversary.25 Thus, paradoxically, the oppressive regimes most likely to be on the receiving end of U.S. sanctions are least likely to alter their behavior, since they are least accountable to their constituents suffering economic hardship.

Coercive actions like sanctions can work well in situations of deterrence. This is when the credible threat of sanctions dissuades a state from pursuing a venture they are not otherwise already engaged in, by raising the perceived cost.26 They work less effectively in situations of “compellence,” where a nation has already invested considerable resources going down a particular path and the coercive action seeks to force them to back off. Denial—preventing the adversary from acquiring the means to engage in harmful activities, such as nuclear weapon components—can work well as a substitute measure in these situations.

When sanctions are effective, it tends to be under the following conditions: they are applied quickly, decisively, and in a multilateral manner; the target is “small and weak;” they are used in pursuit of “modest policy goals;” they are used against semi-democratic rather than authoritarian regimes; they are coupled with positive inducements; and the target believes the sanctions will be adjusted based on its behavior.27 Targeted sanctions, while cheaper to enforce and less damaging to the civilian population, have proven to be even less effective than broad economic sanctions—serving primarily as a symbolic means of signaling U.S. displeasure.28

While economic sanctions have a disappointing track record, financial sanctions have proven to be a potent tool, being “more effective and of shorter duration than trade sanctions.”29 Financial sanctions have succeeded in compelling capitulations on lower-priority issues like money laundering and even major ones like nuclear weapons, and have been effective in inflicting serious damage to the target economy, even for countries with undeveloped financial sectors. However, dealing the appropriate amount of economic damage to a target and converting that damage into political gains remains a challenge.

The case of financial sanctions imposed against Russia following its 2014 takeover of Crimea illustrates how difficult it is to calibrate the tool to the desired objective. The U.S.-imposed sanctions were intended to target the assets of the Kremlin-linked elite, pressuring President Vladimir Putin to return Crimea. However, they coincided with EU sanctions and a global drop in oil prices, doing widespread damage to the Russian economy that the U.S. did not intend.30 This made relations with Russia—a nuclear armed adversary—substantially more hostile. Furthermore, rather than backtrack, the Kremlin expropriated property from liberal-leaning elites to compensate for the losses of Putin’s inner circle.31

Encouraging moral hazard

While sanctions are often conceived as an attempt to take action without using military force, they can incentivize behavior that makes an unwanted military confrontation more likely. When imposing sanctions, the U.S. is essentially trying to cause economic harm that can later be reversed for concessions, but target states can resist by shifting the baseline on other issues of importance to the U.S. They seek to create new, alarming conditions—developing new weaponry or taking provocative military action—that they can later trade for sanctions relief.

Iran did this following U.S. attempts to drive its oil exports to zero in 2019, launching attacks on shipping in the Strait of Hormuz, shooting down a U.S. drone, and violating uranium enrichment caps in the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA).32 Similarly, North Korea expanded its nuclear and missile arsenal despite intensifying U.S. and UN sanctions over the last few years, drawing calls for more forceful military action against the regime.33 In these cases, sanctions were envisioned as a cheap alternative to war—punishing the target state while hopefully changing its calculus. Instead, they increased the probability of a potentially very costly military confrontation.

Speedy removal is difficult

A key impediment to the success of financial sanctions (and indeed all sanctions) is that their power to derive political concessions comes primarily from the promise of their repeal, rather than the economic damage inflicted. When it comes to removing financial sanctions, however, repeal is not a clear-cut process.

Iran, considered the marquee success case for financial sanctions, illustrates this problem. Following Iran’s entry into and compliance with the JCPOA, the five permanent members of the UN Security Council and Germany (P5+1), which negotiated the deal with Tehran, rolled back some of their restrictions on the Iranian financial system and allowed Iran to rejoin SWIFT. This permitted non-U.S. banks to resume business with Iran.

Because the U.S. continued to maintain some sanctions on Iran and parts of the U.S. government were publicly hostile to the JCPOA, however, many foreign banks were afraid to re-enter for fear of running afoul of U.S. law.34 This problem arose even before the U.S. decided to withdraw itself from the agreement. As a result, Iran complained that it did not receive the promised benefits of sanctions relief, and that the U.S. was not adhering to the spirit of the deal.35

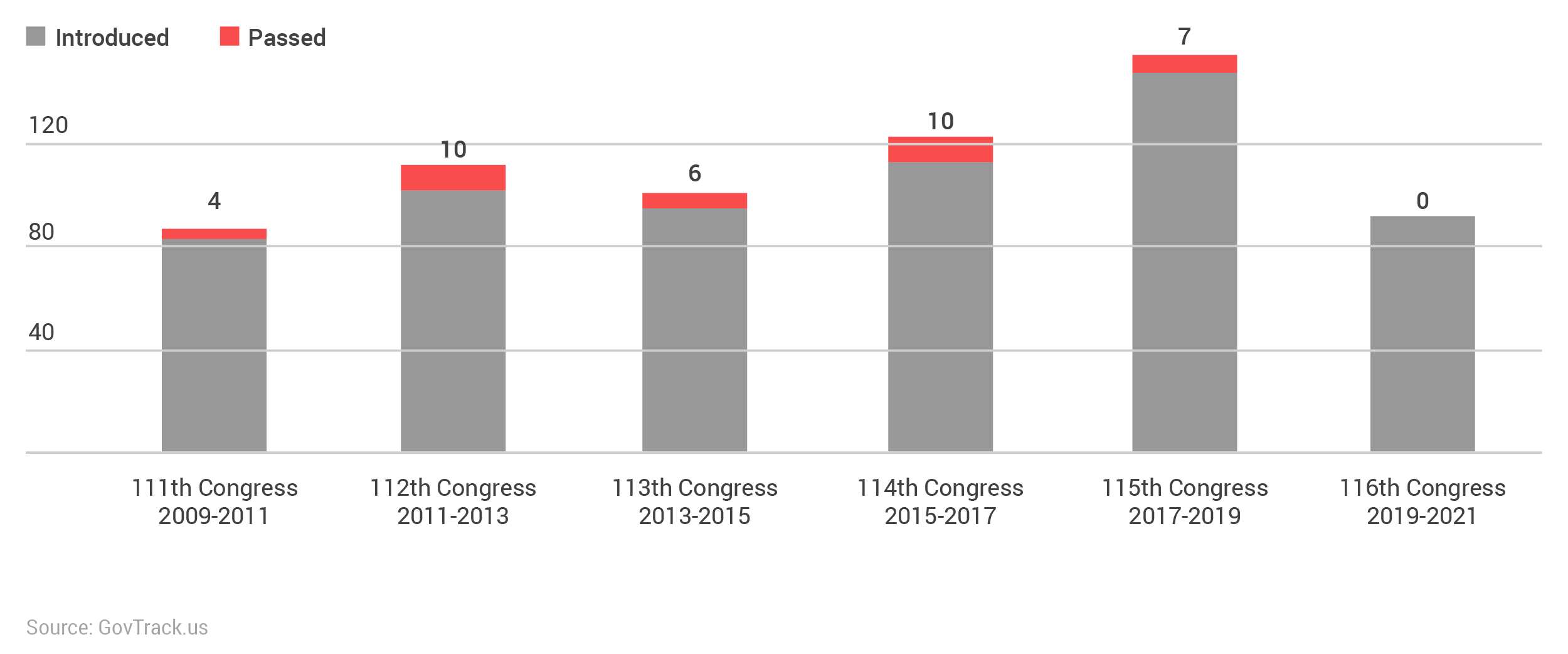

Despite these vulnerabilities, policymakers have become over-reliant on financial sanctions to punish bad behavior or attempt to extract concessions from adversaries and even friends.36 Even in cases where decades of sanctions have failed to yield results, such as Cuba and North Korea, policymakers continue to layer on new punitive measures. Congress in particular has vigorously sought new sanctions—with strong support among members from both parties. As the table below shows, members of Congress have introduced hundreds of bills over the past decade alone seeking to impose sanctions on various nations.

Sanctions bills introduced in Congress and signed into law

Congress has initiated scores of sanctions bills each session over the past decade. Legislative sanctions are especially difficult to reverse or repeal as circumstances change.

Congress’ increased use of sanctions is troubling because laws have tremendous inertia. The status-quo has a strong hold on policy. Therefore, the sanctions prove difficult to lift even after the underlying motivation for them no longer exists. A clear example of this is the Jackson-Vanik Amendment, introduced in 1972 and signed into law in 1975, ostensibly to sanction the USSR for charging a “diploma tax” to emigrating Jewish citizens. The Soviet Union had actually stopped charging these exit fees in late 1972, but the amendment was passed anyway and was not repealed until 2012, nearly a quarter century after the USSR’s collapse.38

As sanctions have proliferated in recent years, a large industry of law firms, think tanks, and other institutions has arisen that has a vested interest in keeping and expanding them, making repeal even harder.39 Given how important timely lifting of sanctions is to their success as a negotiating tool, it is clear that in practice, most sanctions only punish rather than achieve policy change, and thus do nothing but harden the hostility between the U.S. and the target.

IT'S GOOD TO BE KING

The U.S. is the world’s largest national economy, but its economic influence pales in comparison to its dominance of the global financial system. U.S. financial dominance is predicated on three pillars:

- U.S. dollar dominance makes it the world’s foremost reserve currency;

- U.S. banks’ role as a clearinghouse for most global financial transactions; and

- The reach of its regulatory apparatus.

The USD is the global reserve currency, meaning central banks and other financial institutions stockpile USD to make investments and transactions or influence exchange rates.40 Although there are other reserve currencies, USD accounts for more than 60 percent of central bank currency reserves. Furthermore, roughly half of loans worldwide are denominated in USD, and 40 percent of international payments are processed using the dollar.41 Because USD can only be acquired by other nations through the U.S. banking system and thus the Federal Reserve, the U.S. has substantial power to dictate who can participate in the global system simply by managing access to foreigners’ ability to clear and settle dollar transactions.

Breakdown of $10.6 trillion in global reserves by currency (2018)

Central banks prefer holding U.S. dollars as part of their reserves because of its widespread use, stability, and the strength of the U.S. economy.

The centrality of U.S. banks to the correspondent banking system is also a major source of leverage. Correspondent banking refers to “an arrangement under which one bank (correspondent) holds deposits owned by other banks (respondents) and provides payment and other services to those respondent banks.”42 For smaller banks and those outside of major economies, correspondent relationships with multinational financial institutions are key to their ability to transact in other currencies or move funds across borders. The importance of USD as a transaction currency means international banks often need to make loans in USD, in turn requiring them to borrow USD from others. By mid-2018, non-U.S. banks had amassed a staggering $12.8 trillion in USD liabilities.43

Correspondent banking in the global financial system

In the above example, a factory in “Country A” pays for minerals from “Country B.”

Relationships with U.S. banks (or European ones licensed to clear USD transactions) are therefore essential for many financial institutions. When the U.S. government appears unfavorably disposed to specific banks or even whole nations, the main correspondent banks move to sever those relationships, essentially sealing the conduit to the USD or Euro markets for their counterparties.44 Losing access to this massive market is effectively a death sentence for a major financial institution.45 Since the 2008 financial crisis, U.S. banks have overtaken the previously larger European banking sector in profit and market capitalization and have become even more crucial in global finance.46

The importance of the American market to multinational corporations also means the American regulatory system affects nearly every significant economic actor, even outside its borders.47 Firms that run afoul of U.S. sanctions laws can be subject to heavy fines or even locked out of the U.S. altogether. The U.S. is such a crucial market that the Department of Financial Services, a state-level New York regulator with no prosecutorial authority, has been able to extract billions of dollars in fines and force the ouster of executives at foreign banks simply by threatening to revoke their charter to operate in New York City.48

The U.S. also wields substantial influence over the global economic order through institutions like the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, and SWIFT. Because of the close relationship between the U.S. and EU, European regulators often coordinate sanctions activity with the U.S. (as they did against Iran, Iraq, North Korea, and Russia), increasing its effectiveness. The integration of China and Russia’s financial systems into the U.S.-led order also works as a low-level deterrent to hostilities between those nations and the U.S. The certainty that their economies would suffer in the event of conflict augments other key deterrents—U.S. military dominance and the U.S. nuclear arsenal. The interconnectedness of the U.S. and Chinese economies has likely also deterred the U.S. from more forcefully confronting China militarily.

In addition to its political advantages, U.S. financial dominance yields economic gains. Among these is the so-called “exorbitant privilege,” which allows the U.S. to borrow at low interest rates and in its own currency, reducing the cost of debt and minimizing exchange risk.49 Access to capital at such favorable terms permits the U.S. to run long-term deficits and avoid fiscal discipline in a way no other country can.50 The U.S. also generates funds through seigniorage—the money made by selling USD to foreigners—and U.S. banks and firms can do business in their own currency internationally, reducing transaction costs.51

WEAPONIZING ECONOMIC INTERDEPENDENCE

As policymakers have realized the power financial dominance confers, they have weaponized economic interdependence—to use the term coined by political scientists Henry Farrell and Abraham Newman—against an increased set of targets.52 The first major targets of U.S. financial sanctions in the post-Cold War era—Iraq, North Korea, and Iran—were fringe states with few allies. U.S. attempts to isolate them were also multilateral, an approach that has largely been discontinued.

The UN imposed “comprehensive sanctions” on Iraq in 1990, which featured a near total ban on both economic and financial activity with Iraq.53 These sanctions led to a collapse of the Iraqi dinar, a halving of its national GDP, and 5,000 percent inflation over five years.54 Combined with broader sanctions on trade and oil sales, these measures caused lasting damage to Iraq’s economy and society.55 But they failed in their aim of causing political capitulation. Widespread Iraqi suffering did not cause Iraq’s government to back down. Instead, it provided an opportunity for the Hussein regime to consolidate its power over the population by controlling access to scarce necessities.56

North Korea has been under various U.S. economic and financial sanctions since 1950 when it invaded South Korea. It was targeted further in response to its nuclear program when the Treasury Department sanctioned Macau-based Banco Delta Asia in 2005.57 The bank—which was reportedly assisting with North Korean money laundering efforts—was seized by the Macau government, along with North Korea’s assets there. Fear of further U.S. sanctions led two dozen other banks to voluntarily reduce or end their North Korean exposure.58

The financial sanctions seriously hampered the regime’s ability to buy and sell abroad (combined with the broader economic sanctions implemented both unilaterally and through the UN), but North Korea eventually succeeded in acquiring nuclear weapons. New UN and U.S. sanctions imposed during the Trump administration have not diminished North Korea’s ability to expand its arsenal, which it has pledged to keep until it no longer perceives a threat from the U.S.59

Much like Iraq and North Korea, Iran was targeted with a broad array of economic, financial, and individual sanctions against its leadership once it was discovered to have violated its obligations under the Non-Proliferation Treaty in 2005. The U.S., UN, and EU imposed multiple rounds of sanctions between 2006 and 2016.60 The most damaging of these was the removal of Iran’s banks from the SWIFT system in 2012, an unprecedented move that severed Iran’s financial sector from the rest of the world.

The SWIFT sanctions helped drive an already weak economy into contraction. Iranian GDP growth went from roughly 4 percent in 2011 to negative 9 percent in 2012, while by 2013, annualized inflation exceeded 40 percent.61 In 2012, the Iranian currency lost 80 percent of its value. Between 2011 and 2013, oil revenues, which generated 60 percent of the government’s funding, had dropped from $100 billion to $35 billion.62 At the same time, oil exports more than halved from 2.5 million barrels per day (BPD) to 1.1 million. Although many credit the sanctions regime with driving Iran to the negotiating table, plummeting crude oil prices and the self-inflicted wound of economic mismanagement did as much, or more, to get them there.63

FROM MARGINAL STATES TO MAJOR POWERS AND ALLIES

As policymakers became more aware of the ability of financial sanctions to do damage, they increasingly became a response of first resort for expressing U.S. displeasure, even toward major powers like Russia and allies like Turkey. Following Russia’s seizure of Crimea in 2014, the U.S. and EU implemented a growing list of financial sanctions that targeted scores of Russian individuals, companies, and banks, including major state-owned banks Gazprombank and Vnesheconombank.64 The sanctions also restricted exports of equipment for the energy and arms sectors. Several U.S senators publicly advocated for punishing Russia by expelling it from SWIFT, a move which was ultimately not adopted.65 The sanctions on Russia, combined with lower global prices of oil (Russia’s primary export) led the ruble to lose more than half its value against the dollar from 2014 to 2016.66

Similarly, as a result of the conflict between the U.S. and Turkey over the imprisonment of American pastor Andrew Brunson and other matters, the U.S. imposed financial sanctions on two top Turkish officials.67 These sanctions were quickly followed with a doubling of tariffs for Turkish steel and aluminum, leading the lira to drop by 20 percent and the Turkish president to declare America’s actions an “economic war.”68 These sanctions were unique in that they were imposed on a treaty ally and NATO member at a time when its currency was already weakening, with the explicit intent of generating political pressure by hurting its economy.

The U.S. almost imposed sanctions on a powerful ally yet again as Jamal Khashoggi’s murder frayed relations between the U.S. and Saudi Arabia.69 Members of Congress argued for sanctions against the Saudis, and the Kingdom responded by threatening to hit the U.S. where it hurt—by selling oil in Chinese renminbi (RMB) instead of USD.70 Had an RMB market for oil actually been created, it would have represented a remarkable about-face for the Saudis. The Kingdom’s traditional policy of selling its oil for USD on the international markets remains a core driver of demand for USD since the end of the gold standard.71 Although the administration wisely sidestepped a potential crisis, the proposed Saudi countermeasures showed an increasing willingness by even an ostensible ally to go after the source of U.S. financial dominance.

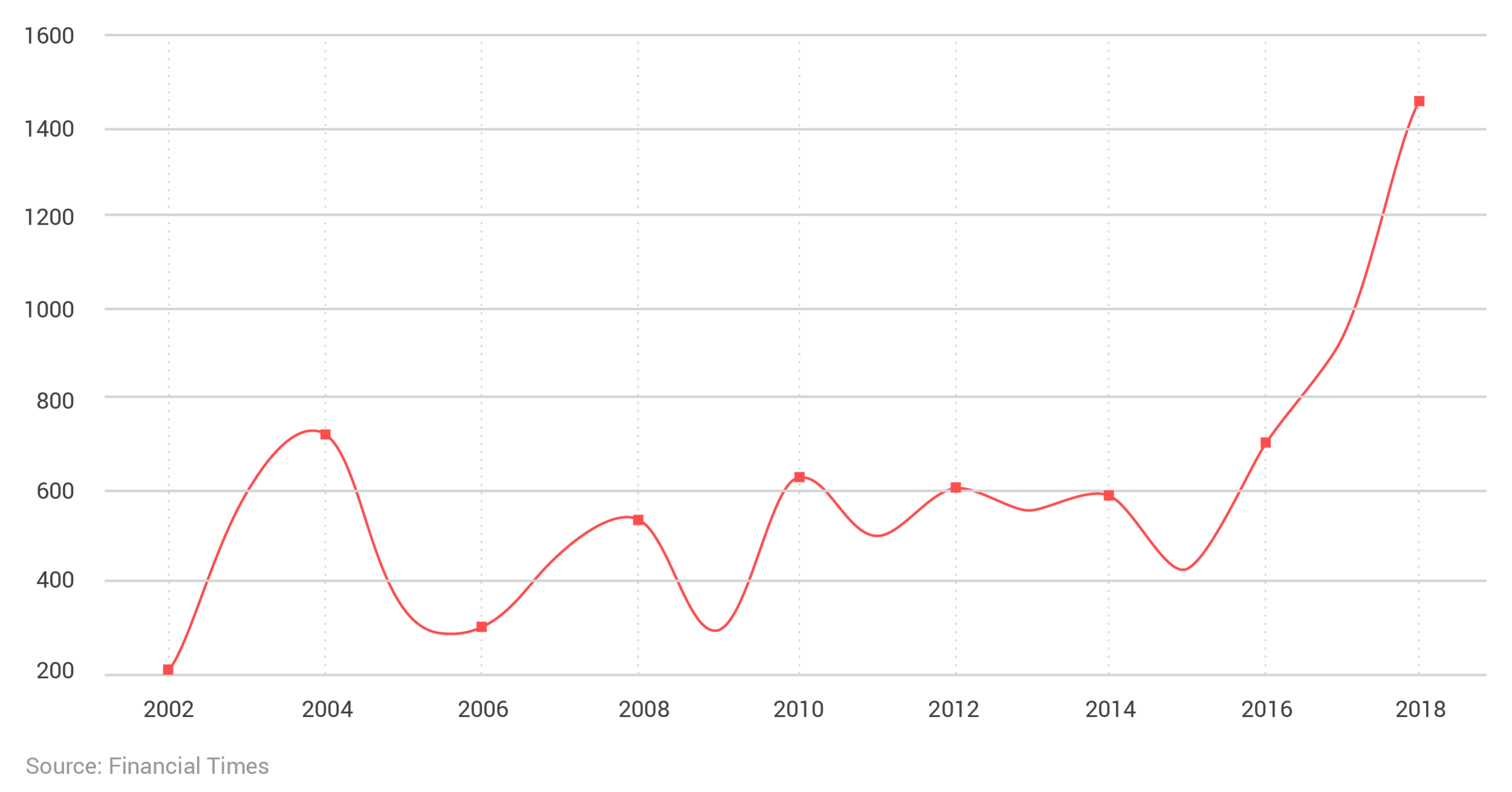

New entities targeted by U.S. sanctions from 2002–2018

The number of new entities targeted by U.S. sanctions has spiked significantly during the second half of the decade.

Tightening the Net with Secondary Sanctions

As the U.S. has become more comfortable with financial sanctions, it has also taken to using secondary sanctions to completely isolate targets even from neutral third parties. An example is the Helms-Burton Act of 1996, which allows suits in U.S. courts against foreign companies doing business with the Castro regime in Cuba.72 The passage of the act led the Europeans and Canada to pass “blocking statutes,” which forbid their companies from cooperation with U.S. sanctions efforts.73 De-escalation was achieved before the conflict came to a head after the Europeans and the Clinton administration agreed not to pursue sanctions against each other.

The August 2017 passage of the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA) stimulated new secondary sanctions, with the act prescribing punishments for third-party entities transacting with sanctioned nations like Russia, Iran, and North Korea.74 That same month, the Treasury Department imposed secondary sanctions on Chinese and Russian firms doing business with North Korea, and contemplated but did not follow through on sanctions targeting Chinese banks.75 In September, the U.S. sanctioned the Chinese military’s weapons development department following the purchase of Russian weapons in violation of U.S. sanctions on Russia.76

More recently, the chief financial officer of Chinese tech giant Huawei was arrested in Canada at the request of the U.S. for allegedly helping violate sanctions on Iran, sparking a diplomatic row and the retaliatory arrests of Canadians in China.77 The U.S. has followed up with criminal charges against Huawei itself for sanctions evasion and other crimes, a move that is a negotiating chip in a trade dispute, but also likely to further harm U.S.-China relations.78

Recently, the U.S. has begun threatening to use secondary sanctions to coerce allies. Turkey was repeatedly threatened with sanctions under CAATSA for purchasing Russia’s S-400 air defense system instead of the U.S.-made Patriot. The Erdogan government proceeded with the purchase anyway, and will now likely be subject to the mandatory sanctions enshrined in the law for major buyers of Russian defense equipment.79 The administration has done its best to stall the implementation, but it appears Congress will eventually force the president’s hand.

Following the U.S.’s unilateral withdrawal from the JCPOA, the U.S. also threatened EU companies with sanctions unless they cease business activities with Iran, even while the EU continues to adhere to the deal. Despite the strenuous objections of EU leaders and their claims of a breach of sovereignty, the U.S. has successfully pressured European companies, and even the nominally independent Belgium-based SWIFT, to once again sever ties with Iran.80

The EU lacks an effective mechanism to shield its corporations from U.S. sanctions. Although EU law can protect them within its jurisdiction, all European companies need to access the global banking system, and often have customers or suppliers associated with America’s economy, easily exposing them to U.S. financial sanctions.81 In an attempt to provide some legal shelter for companies doing business in Iran, the EU recently updated the decades-old Blocking Statute that originated with Helms-Burton, forbidding European companies from cooperating with U.S. sanctions, negating any legal judgments against European firms arising from sanctions, and allowing European companies to file suit for damages incurred as a result of sanctions.82

Ironically, these rules accelerated the rate at which major European companies left Iran. Under the Blocking Statute, European companies would have to explain a decision to exit Iran to the EU authorities, who at the same time lacked the ability to truly protect them from U.S. retaliation. Caught between European law and the credible American threat of huge fines, major firms like Total, Maersk, and Allianz opted to leave Iran immediately for “business reasons” once the updated rules were proposed, rather than formally defend their decision following the Statute’s passage.83

A similar scenario played out with SWIFT. Although SWIFT is a nominally independent institution governed by European law, the U.S. possessed multiple ways to punish non-compliance. It could sanction SWIFT directly (albeit at a big cost for global financial stability), issue visa bans and asset freezes for its board of directors, or directly target member banks that fail to comply with sanctions through fines and criminal charges.84 The U.S. ultimately did not have to actually carry out any of these measures, as despite the EU’s best efforts, SWIFT participated in renewed U.S. sanctions—the messaging service was forced to suspend several Iranian banks.85

The ease with which the U.S. was able to ignore a multilateral legal framework to which it had signed on, and compel compliance by corporations around the world motivated the EU, Iran, China, and Russia to work together to build alternative channels of keeping the deal afloat.86 This development threatens to further undermine the effectiveness of U.S. sanctions—because the EU is a crucial partner whose cooperation the U.S. often relies on in sanctions enforcement—and could also undermine cooperation in other policy areas.

More recently, the U.S. has also returned to a hardline embargo policy against Cuba that features punitive measures against foreign and domestic firms. Title III of the Helms-Burton Act that tightened sanctions on Cuba allows Americans to sue foreign companies that benefit from properties confiscated by the Cuban government after the revolution.87 It has traditionally been suspended in six-month intervals since the law was passed. But the law was allowed to go into effect in April of 2019, opening the door for as many as 200,000 lawsuits to be filed against long-established foreign companies on the island, and rankling relations with allied governments in Europe and Latin America.88

TARGETS OF U.S. SANCTIONS

As noted earlier, sanctions tend not to change the target state’s political behavior, leading to the continual imposition of more and more sanctions in an attempt to achieve the goal. The usual result is that the target state, feeling besieged but without an opportunity to arrive at a compromise, continues to defy U.S. demands. Allies can also peel off from a multilateral sanctions effort over time if they feel the U.S. is being unreasonable.

U.S. sanctions imposed on major targets

Where the U.S. imposes one type of sanction, it tends to layer on others as well.

In aggressively enforcing secondary sanctions, the U.S. is essentially claiming an expansive right to impose its own laws internationally, even where third parties are transacting with each other in compliance with their own laws.89 Again, the U.S. has this clout because of two advantages competitors lack—its dominant position over key aspects of the global financial system and a set of highly developed institutions.90 These advantages allow it to exploit the “weaponized interdependence” created by an interconnected global financial system.91 Such an approach is not without consequences, however.

CHALLENGES TO U.S. FINANCIAL HEGEMONY

The U.S. has dominated the global financial system for a long time. As long as other nations perceived U.S. power to be exercised judiciously and with a nod to their interests, they had no incentive to pursue radical change. But as the U.S. weaponized this system in recent years, the risk of relying on U.S. goodwill has become evident to other nations, leading them to take steps to counter American dominance. This manifests primarily in efforts to build alternative infrastructure and moves to chip away at the dominance of the dollar.

Russia and China have been two of the first movers in this regard, due to their size and role as traditional rivals of the U.S. After the first round of sanctions forced Visa and Mastercard, two major payment processors in Russia, to cut ties with some of their customers, Russia introduced a national payment system known as Mir in 2014.92 It also developed a domestic messaging service known as SPFS that mirror’s SWIFT’s function.93

Since then, it has taken steps to strengthen this system by having state banks wind-down relationships with American payment processors and reduce their USD holdings.94 According to its deputy prime minister, Russia has also hardened its financial system so it can operate independently in case it is severed from SWIFT.95 In 2019, Turkey, which has increasingly been at odds with the U.S., became the first non-Russian speaking country to begin accepting Mir payments.96

For its part, China—a growing economic power with a GDP that may surpass the U.S. as early as 2030, and which already has in terms of purchasing power parity—has launched several new institutions to challenge the U.S.-led equivalents while simultaneously attempting to increase the prominence of the RMB.97 These include the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), and the Cross-Border Interbank Payment System (CIPS).98

The AIIB is designed as a World Bank equivalent for Asia where China is the dominant shareholder, as opposed to the Asian Development Bank dominated by Japan and the U.S. It is currently making loans in USD but looking to eventually expand into RMB. BRI is an infrastructure funding effort for developing nations that incentivizes increased use of RMB among loan recipients. CIPS, an RMB-based SWIFT equivalent, is particularly important to strengthening the RMB by “providing the infrastructure that will connect global RMB users through one single system.”99 It also provides a mechanism for China to continue to operate its banking system should it be sanctioned from SWIFT, and allows it to carry out transactions that are harder for Western intelligence services to monitor.100

China has also sealed well over $400 billion worth of trade swap agreements with partners like Argentina, Indonesia, and Pakistan since 2008, using the RMB and partner states’ currencies to bypass the dollar entirely in those country-to-country transactions.101 Recently, China struck a $30 billion swap with Japan, which the Chinese government-affiliated Global Times called “clearly a significant step toward eroding the USD’s status in the global financial system” and a response to the “U.S. government’s reckless, unilateral moves.”102

During the Cold War, the Soviet Union played the role of “black knight” in U.S. sanctions policy, driving additional business and economic support to nations sanctioned by the U.S. in order to help them resist U.S. pressure.103 While no state has emerged as the clear successor to the Soviets in this role, China appears to be the most likely candidate. Chinese support helped keep both North Korea and Iran afloat during stringent U.S. sanctions, although primarily to advance its own economic and political interests rather than sabotage U.S. policy. As U.S.-China relations continue to degrade due to trade and political disputes, China’s role as a “black knight” will likely become more pronounced.

Both China and Russia have also dramatically increased their purchases of gold over the last 15 years, presumably to strengthen their currencies and reduce their dependence on dollar reserves. Gold was instrumental in Iran’s ability to continue trading when under U.S. sanctions prior to the JCPOA, and thus would no doubt also be useful to manage payments in the event of a financial or actual war between the U.S. and Russia or China.104

Europe has also tried to increase its independence from the U.S. following America’s withdrawal from the JCPOA. Given the success the U.S. has had in deterring European companies from doing business with Iran and forcing SWIFT to evict Iranian banks from the system, it became obvious that where U.S. and European security and prosperity interests diverged, the U.S. was willing and able to run roughshod over the Europeans.105 The French foreign minister complained that Europe was in danger of becoming an American “vassal,” while the German foreign minister pushed for a European alternative to SWIFT that was insulated from U.S. pressure.106

To help continue to facilitate trade with Iran, the Europeans launched a Special Purpose Vehicle, the “Instrument In Support of Trade Exchanges (INSTEX),” whose headquarters are in the French Ministry of Economy and Finance.107 INSTEX provides a platform for handling trade-related payments through a barter-like system of credits that would not require the exchange of money, thus circumventing financial controls on Iran.108

The U.S. initially expressed strong opposition to INSTEX, rightly viewing it as an attempt to create a viable means of circumventing U.S. financial dominance.109 Ironically, when Iran began violating the JCPOA following the U.S. withdrawal, some American officials quietly began hoping INSTEX succeeded as a way to keep Iran compliant with the deal’s nuclear restrictions.110 Although at present, INSTEX is far from a viable alternative to the U.S. financial system given the relatively small volume of business it handles, the determined attempt to move forward in the face of intense U.S. pressure signals Europe’s growing resentment at American heavy-handedness and desire to limit U.S. dominance of global finance.

ASSESSING THE CONSEQUENCES

The growing pushback to U.S. dominance has not yet materialized into a full-fledged decline of the dollar and American banking influence. Building credible alternatives is an expensive and time-consuming effort. Currency dominance tends to outlast economic dominance—the pound remained the dominant currency for 70 years after the American economy overtook the British economy.111

China achieved a major victory for the RMB when it was added to the IMF’s special drawing rights basket of currencies in 2016, making it an official reserve currency.112 Despite this success, the RMB comprises only roughly 2 percent of central bank reserves, and relatively little global trade is conducted in RMB.113

Capital markets that are “open and free of controls, but also deep and well-developed” are crucial to fostering a truly international currency.114 Private property rights—the ability to use a currency to securely purchase and then sell that country’s assets, are also essential. China’s extensive capital controls and the central’s bank’s active management of the RMB’s price are a major barrier to widespread adoption of the RMB by foreign investors.

Dominant global currencies in the past six centuries

Foreign investors’ inability to purchase assets in China and be guaranteed proper legal protection is another barrier—not to mention the uncertainties about whether they will be able to get their money out. A substantial shift in the Chinese government’s approach to regulation in financial and capital markets, and maybe even better legal protections that would require a change in governance, would be necessary to attract significant foreign interest in the RMB.

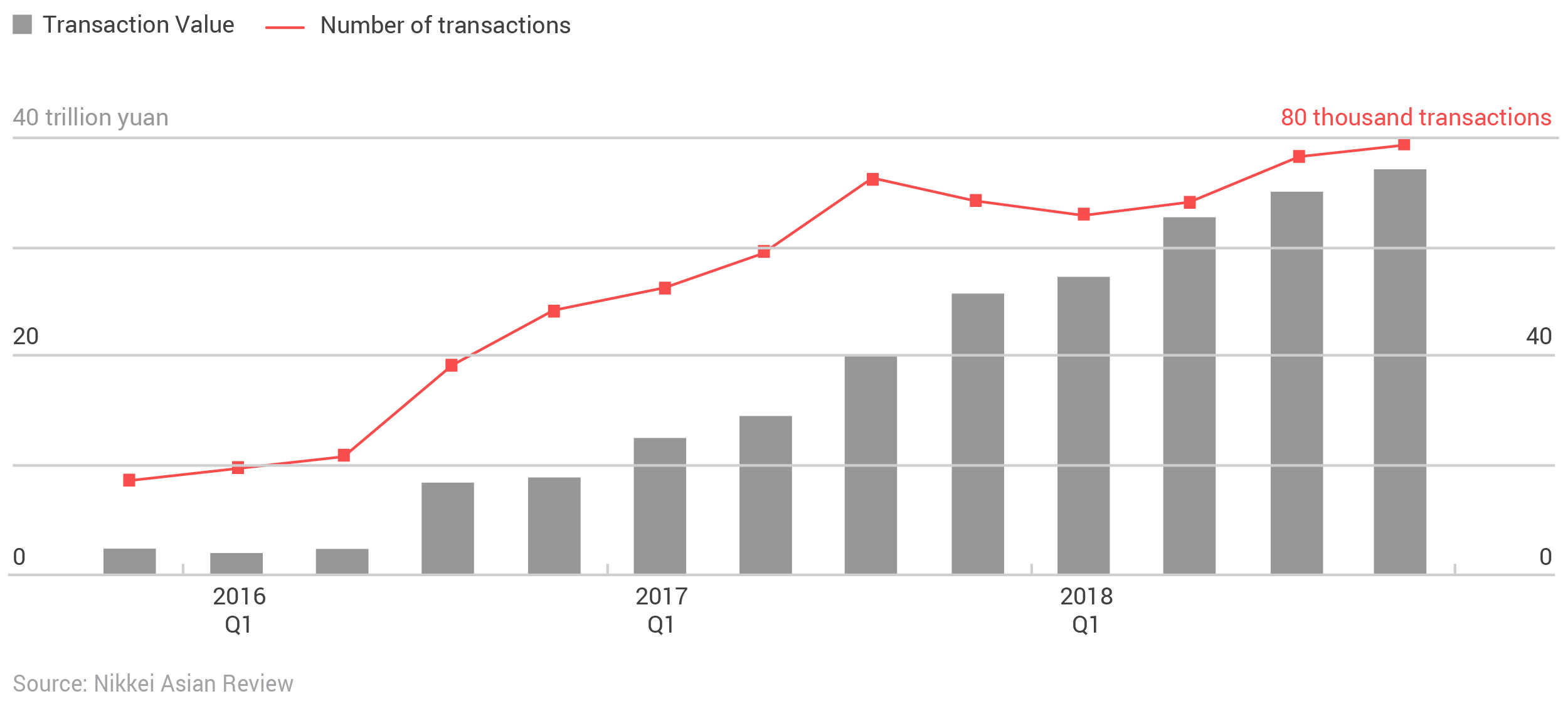

Nevertheless, China is trying. CIPS has come a long way since its 2015 founding. It has grown from 19 direct participants and 176 indirect participants at its inception to 31 direct participants and 829 indirect participants today, while also expanding service to cover more time zones and standardizing its protocols to bring them in line with SWIFT.115 It has also significantly expanded both in the volume and value of transactions it handles.

The growth of CIPS, China’s native payment clearing and settlement system

China’s payment clearing and settlement system has seen rapid growth since its launch in 2015.

Similarly, the BRI, while facilitating increased use of RMB in some areas, has seen a decline of RMB use in others.116 Out of the 68 BRI nations, 33 are rated below investment grade, suggesting that they pose too much of a credit risk to secure development loans on the open market.117

China’s willingness to fund projects in these nations will no doubt buy loyalty from their governments, but China will pay for this privilege in the form of higher than normal defaults. Politically, however, as long as China is able to bear the cost of these projects, it will have an easier time pushing adoption of its own currency, commercial norms, and financial institutions among the participants.

Russia by itself can chip away at the USD and dollar-based institutions, but it lacks the financial heft (its GDP is just $1.6 trillion versus $19.4 trillion for the U.S.) to do major damage unless it is integrated into a major coalition.

The EU’s drift from the U.S. is more alarming, since the Euro is the closest thing to a peer competitor for the USD, accounting for roughly 20 percent of global central bank reserves, second only to the dollar.118 At the same time, the EU requires consensus to function, is politically fractious, and the U.S. can slow the bloc’s initiatives by peeling off member states.119

Snapshot of China’s “Belt and Road Initiative”

China’s Belt and Road Initiative attempts to fill a massive infrastructure financing need in developing Asia, and could impact more than half the world’s population and a quarter of the world’s economy.

The Scope of Sanctions

As former Fed Chair Paul Volcker said, “Exorbitant privilege is also an invitation or temptation to lack discipline,” and this has been borne out in the sheer scope of U.S. sanctions policy.121 The U.S. currently imposes about 8,000 distinct sanctions affecting targets across the vast majority of countries—undermining the trust and relationships that underpin the global economic system.122 In the near term however, the most severe consequences for overactive sanctions use will be political and diplomatic. Frustration at U.S. heavy handedness is driving diplomatic blowback and making allies more willing to depart from their traditional acquiescence to U.S. policy objectives. The EU, whose cooperation on Russian and Iranian sanctions among others was crucial to their bite, has grown frustrated with the U.S., and is unlikely to be as cooperative in the future when dealing with other problem nations.

Distribution of parties sanctioned by the U.S.

Almost every nation in the world has some person or entity currently facing U.S. sanctions.

Europe’s continued commitment to remain in the Iran deal despite U.S. opposition highlights its growing desire for “strategic autonomy.”123 The Europeans have been counseling Iran on how to make the deal work despite the U.S.’s withdrawal, and have reportedly advised Iran to wait out President Trump’s term in the hopes of receiving more favorable treatment from another administration.124

Even in Venezuela, where there is widespread global support for sanctions against the Maduro regime, U.S.-EU acrimony has made the formation of a unified policy difficult. In Iran, the damage dealt to the economy by U.S. sanctions has made the public skeptical of the value of negotiating with foreign powers, highly supportive of attempts to acquire missiles and develop a nuclear program, and has created an overwhelming majority who view the U.S. unfavorably.125

China and Russia, whose initial support was crucial in securing UN sanctions on Iran, have been pushed away as a result of latest round of unilateral U.S. sanctions. It is highly unlikely the U.S. will be able to rely on them in future attempts to pressure Iran or any other state where their own interests are not explicitly involved.

Given that multilateralism is an important component of effective sanctions, this is a problematic trend.

LOOKING TO THE FUTURE

Despite the strong grip the U.S. exerts on global financial infrastructure, U.S. financial power has begun to degrade in some areas. The dollar accounted for 72 percent of global reserves in 2001. Today, that figure is down to 62 percent.126

Under pressure from aggressive money-laundering regulations, Western banks have also engaged in widespread de-risking since the financial crisis, severing correspondent banking relationships with mostly developing world clientele.

Between 2009 and 2016, there was a drop in the number of USD- and Euro-based correspondent relationships of 15 percent and 23 percent, respectively, while Chinese-based correspondent relationships grew by 3,355 percent over the same period.127

Growth of banking system by size of assets (trillions)

Since the financial crisis, China’s banking sector has boomed, the U.S. banking sector has grown slightly, and Europe’s banking sector has declined significantly.

As Western banks have de-risked, financial traffic has either shifted to competitors or moved to grey and black financial markets.128 Should this trend continue, it will reduce the use of USD in financial activity outside the main global economic hubs. It will also allow competing firms abroad, many of them from rival powers like China, to capture developing markets at a time when U.S. financial institutions are handicapped by their strict compliance.

New technologies are also leapfrogging some of the institutions that act as chokepoints in the financial system. Cryptocurrencies and blockchain technology are facilitating financial transactions that are difficult to prevent by any one state.

Ripple, a blockchain company started in 2012 and currently boasting over 200 bank partnerships, has developed technology that allows both messaging and extremely cheap, nearly instantaneous point-to-point payments.129

Should it become widespread, this technology would present an appealing alternative to both SWIFT and correspondent banking. Highly secure “privacy coins” like ZCash and Monero also facilitate anonymous transactions, helping evade traditional monitoring and compliance systems.130 It is no accident that states targeted for sanctions by the U.S., including Russia, Venezuela, and North Korea, have been actively experimenting with cryptocurrencies.131 The more aggressively the U.S. employs sanctions to target adversaries’ ability to transact, the more investment and partnerships will flow to technological innovators that can circumvent these barriers, accelerating the current system’s decline.

Cryptocurrencies do have limitations, of course, and are unlikely to replace the traditional banking system. For the time being, they are nowhere close to providing the liquidity of reputable government-backed currencies, or commanding the public trust held by the traditional banking system.132

What they do provide is an alternative avenue for states or organizations to carry out international business without the consent of the U.S. or the buy-in of traditional financial gatekeepers.

Should alternative systems gain serious traction and U.S. financial sanctions continue to reduce the luster of the USD and U.S. debt for foreign governments and corporations, the U.S. would bear substantial political and economic costs. On the political side, one risk is lost influence to combat various threats. As a recent report noted:

Global dependence on access to the dollar gives Washington leverage to coordinate battles against terrorism and cybercrime, to shape rules against corruption and tax avoidance, and to protect privacy through the regulation of global data flows.133

Decreased foreign dependence on the USD would translate to reduced influence on these issues and decreased ability to effectively pressure states like North Korea when it truly matters.

Economically, a fragmentation or balkanization of the international financial infrastructure could reduce the value of the dollar and drive up the cost of financing U.S. debt, even if the U.S. continues to lead the largest emergent system.

A shift in central bank purchases away from USD toward other currencies would represent a significant reduction in demand and lead to a devaluation of the dollar. That is not necessarily bad for the U.S. in the long term, as it would make U.S. exports more competitive, and force fiscal discipline in Washington. But in the short to medium term, it would drive up the price of all imports, and erode the American standard of living in an economy that imported $2.4 trillion worth of goods in 2017 alone.134

Already, the U.S. federal government has amassed national debt that exceeds 100 percent of GDP and has run annual deficits of between $400 billion and $1.4 trillion over the past decade, a figure that is expected to increase as federal spending grows.135

Waning interest in U.S. Treasury securities (“Treasuries”) by major foreign buyers of U.S. debt (or worse, a selloff of existing holdings) would shift the financing burden onto the American people, through some combination of lower growth, lower government spending, higher taxes, and inflation.136

Annual U.S. federal government deficits from 1989–2018 (billions)

Even without counting intragovernmental debt, the U.S. is consistently running massive deficits, making it vulnerable to a spike in interest rates.

That shift could be politically destabilizing in the U.S. Net interest payments in the 2019–2020 fiscal year amount to $479 billion, exceeding the annual cost of Medicaid.137 By 2027, even at the modest interest rate projections of 3.7 percent, the U.S. government will pay $788 billion in interest, surpassing the projected defense budget for that year and accounting for 13 percent of federal spending (up from roughly 9 percent in 2019).138 Should a loss of confidence in Treasuries spike interest rates far above those projections, the U.S. could be paying $1 trillion annually in interest alone.

While a full-scale withdrawal from Treasuries would be costly for major investors like China and Japan, declining foreign participation in Treasury auctions is already happening. The share of foreign-held Treasuries has dropped from 50 percent in 2013 to 40.5 percent today, mostly as a result of reduced buying by China and Japan.139 Russia, which has been hard hit by repeated sanctions, reportedly sold all of its Treasuries and most of its dollar-denominated assets in the past year.140

U.S. financial dominance is guarded by the high cost of building alternatives and the network effects of the USD. But whenever the U.S. weaponizes private financial institutions, it changes the cost-benefit calculus, making alternatives increasingly worth their startup costs. When financial warfare targeted only rogue states with minimal impact on the global system, the blowback was limited. The heavy-handed approach pursued over the last few years, however, is increasingly alienating all the major economic players outside of the U.S. Once other nations commit to the investment necessary to build a new system and establish a base of users, the shift away from the U.S. system would be difficult to reverse. We are likely at such a crossroads today.

The major changes in the global oil market in recent years illustrate this point. While the OPEC nations dominated the market for decades and wielded their influence both for profit and political ends, over the last 15 years rising prices and concerns about dependence on foreign oil supplies made hydraulic fracturing (fracking) in the United States commercially viable for the first time.141 In the last decade, U.S. oil production nearly doubled, and OPEC found its market dominance permanently reduced, a change that will be further cemented as more countries explore the use of fracking to access their own reserves. Just as the abuse of OPEC’s cartel power played to America’s advantage in this case, careless use of our financial power and the subsequent development of alternative financial institutions would be hugely detrimental to our national interests.

As Europe contemplated how to build INSTEX, one of the key questions it considered was whether to invite Russia and China to participate.142 Russia and China are not natural allies with each other or with the EU, and this sort of cooperation against the U.S. is exactly what policymakers should seek to avoid. This can best be achieved by using financial coercion cautiously, sparingly, and in a sequenced and prioritized manner, where potential unintended consequences are identified and steps are taken to mitigate them. The U.S. should be particularly careful about avoiding further secondary sanctions that could sour relations with allies or third parties, and compel them to find common cause with America’s adversaries. Should the U.S. continue its current path, outside actors will take more and more steps to chip away at American financial dominance wherever they are able, degrading the reach and stability of the dollar system. Squandering the exorbitant privilege this way would be a historic mistake but is still very much avoidable.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The political utility of sanctions makes it difficult to recalibrate the U.S. sanctions apparatus in the near term, but there are several steps the U.S. can take to reduce the incentives spurring alternative financial infrastructure. The U.S. should be cautious about the use of secondary sanctions on allies—particularly against those with large, influential economies—and use them in those cases only sparingly and when better alternatives are lacking. A more modest first step is to waive secondary sanctions on Europe for purchasing Iranian oil, thereby negating the need for INSTEX or similar measures, and allowing this experimental institution to dissolve before it becomes truly viable.

The provisions in CAATSA that impose mandatory sanctions under certain circumstances should also be repealed. This would allow sanctions decisions to be made on a case-by-case basis and after a serious assessment of the cost-benefit to deploying them in a particular circumstance. New sanctions, whether imposed by Congress or the executive branch, should be screened for the following criteria to ensure they have the best chance of achieving desired political outcomes:

- Sanctions should provide a clear statement of intent that outlines what behavior will get the sanctions either lifted or enhanced. There should be some stability and consistency to U.S. demands over time, both to create predictability for the target and to make it easier to benchmark how sanctions are performing against their intended goals.

- The target should ideally be offered a window of time in which to change its policies before sanctions take effect. It is difficult for foreign leaders to walk back a policy while still saving face domestically after sanctions are imposed.

- Legislation should include sunset clauses with reasonable timeframes so sanctions do not remain on the books forever unless Congress still deems it worth keeping.

- Sanctions should be accompanied with a required Treasury assessment of the cost to the American economy, in order to better assess their relative value.

This last point is particularly important, as despite 8,000 U.S. sanctions currently in place, policymakers have no reliable data about how much that forgone business has cost the American economy. China for example is investing $400 billion in Iran while U.S. sanctions lock out all of China’s competitors, indicating the current sanctions regime is imposing potentially massive opportunity costs on American companies.143

A recent Government Accountability Office report observed that the agencies tasked with implementing sanctions “analyze the impacts of specific sanctions on a particular aspect of the sanction’s target—for example, the sanctions’ impact on the target country’s economy or trade, according to agency officials. However, these assessments do not analyze sanctions’ overall effectiveness in achieving broader U.S. policy goals or objectives, such as whether the sanctions are advancing the national security and policy priorities of the United States.”144

Officials argued that tracking the performance of sanctions relative to U.S. goals was difficult because policy goals often shift, isolating the impact of sanctions from other factors is tricky, and reliable data is at times lacking. However, the officials interviewed also noted that “there is no policy or requirement for agencies to assess the effectiveness of sanctions programs in achieving broad policy goals,” and hence they preferred to shift scarce resources toward the easier task of measuring impact on the target rather than political gains.145

By requiring agencies involved in the sanctions process to regularly assess whether sanctions are serving broader U.S. goals instead of simply harming the target’s economy, and properly resourcing that effort, Congress can make this tool more effective.

The executive branch should also ensure that sanctions action from the Treasury Department is accompanied by a parallel diplomatic process with the target country at the State Department, in order to negotiate the political concessions the action is intended to achieve. Successful diplomacy on sensitive issues (nuclear weapons, territorial conquest) will often require the U.S. to make some concessions other than scaling back sanctions—there is no such thing as “something for nothing” when asking other states to compromise on what they perceive to be their core interests.

By acknowledging the limitations of U.S. financial power—and using it strategically and in pursuit of clear, attainable goals—the U.S. can better preserve that power, and the prosperity its ubiquitous financial influence underpins well into the future.

Endnotes

1 “Economic Sanctions: Agencies Assess Impacts on Targets, and Studies Suggest Several Factors Contribute to Sanctions’ Effectiveness,” Government Accountability Office, pg. 12, October 2019, https://www.gao.gov/assets/710/701891.pdf.

2 Gary Clyde Hufbauer, Jeffrey J. Schott, Kimberly Ann Elliott, and Barbara Oegg, “Economic Sanctions Reconsidered,” Peterson Institution for International Economics, November 2007, https://piie.com/bookstore/economic-sanctions-reconsidered-3rd-edition-paper.

3 “Bretton Woods Conference,” Encyclopedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/event/Bretton-Woods-Conference.

4 “The Bretton Woods Conference, 1944,” U.S. Department of State, https://2001-2009.state.gov/r/pa/ho/time/wwii/98681.htm.

5 Robert Mundell, “A Reconsideration of the Twentieth Century,” American Economic Review 90, no. 3 (June 2000): 327-340, https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/aer.90.3.327.

6 Jonathan Masters and Andrew Chatzky, “The World Bank Group’s Role in Global Development,” Council on Foreign Relations, April 9, 2019, https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/world-bank-groups-role-global-development.

7 Harold James, “Bretton Woods to Brexit,” International Monetary Fund, Finance & Development 54, no. 3 (September 2017): 4–9, https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2017/09/james.htm.

8 Mamdouh G. Salameh, “Salameh, Mamdouh G., Has the Petrodollar Had its Day?” USAEE Working Paper No. 15-216, June 22, 2015, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2621599.

9 Ronald McKinnon, “The World Dollar Standard and Globalization: New Rules for the Game?” Stanford Center for Global Development, September 2003, https://kingcenter.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/publications/181wp.pdf.

10 James Grant, “The End Of The Petrodollar?” American Foreign Policy Council, March 20, 2018, https://www.afpc.org/publications/articles/the-end-of-the-petrodollar.

11 Grant, “Petrodollar.”

12 “SWIFT history,” Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication, 2019, https://www.swift.com/about-us/history.

13 “Foreign exchange turnover in April 2016,” Bank of International Settlements, September 2016, https://www.bis.org/publ/rpfx16fx.pdf.

14 Gary Clyde Hufbauer, Kimberly Ann Elliott, Tess Cyrus, and Elizabeth Winston, “US Economic Sanctions: Their Impact on Trade, Jobs, and Wages,” Peterson Institute for International Economics, 1997, https://ideas.repec.org/p/iie/wpaper/wpsp-2.html.

15 Elena Servettaz, “A Sanctions Primer: What Happens to the Targeted?” World Affairs 177, no. 2 (2014): 82–89, https://www.jstor.org/stable/43556206?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents); Peter Rutland, “The Impact of Sanctions on Russia,” Russian Analytical Digest 157, December 17, 2014, https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/186842/Russian_Analytical_Digest_157.pdf.

16 Juan Zarate, Treasury’s War: The Unleashing of a New Era of Financial Warfare, (New York: Public Affairs, 2013).

17 Taehee Whang, “Playing to the Home Crowd? Symbolic Use of Economic Sanctions in the United States,” International Studies Quarterly 55, no. 3 (September 2011): 787–801, https://academic.oup.com/isq/article-abstract/55/3/787/1834344.

18 Gary Clyde Hufbauer, Jeffrey Schoot, Kimberly Ann Elliott, Barbara Oegg, “Economic Sanctions Reconsidered,” Peterson Institute for International Economics, 2009, A. Cooper Drury, “Sanctions as Coercive Diplomacy: The U.S. President’s Decision to Initiate Economic Sanctions,” Political Research Quarterly 54, no. 3 (2001): 485–508, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/106591290105400301; Robert Pape, “Why Economic Sanctions Still Do Not Work,” International Security 23, no. 1, (Summer 1998): 66–77, https://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/abs/10.1162/isec.23.1.66?journalCode=isec; Bryan Early, Busted Sanctions: Explaining Why Economic Sanctions Fail, (Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 2015).

19 Jon Gambrell, “Iran looks warily to China for help as US sanctions resume,” Associated Press, September 12, 2018, https://apnews.com/b664060c6d5c46f3917ebb920f2af712.

20 Shubhangi Pandey, “U.S. sanctions on Pakistan and their failure as strategic deterrent,” ORF Issue Brief, August 1, 2018, https://www.orfonline.org/research/42912-u-s-sanctions-on-pakistan-and-their-failure-as-strategic-deterrent/.

21 “Despite Looming U.S. Sanctions, the Nord Stream 2 Pipeline Will Likely Proceed,” Stratfor, July 17, 2019, https://worldview.stratfor.com/article/despite-looming-us-sanctions-nord-stream-2-pipeline-will-likely-proceed.

22 Enea Gjoza, “U.S. Sanctions Will Not Stop Turkey’s Shift Towards Russia,” The National Interest, August 14, 2019, https://nationalinterest.org/blog/middle-east-watch/us-sanctions-will-not-stop-turkeys-shift-towards-russia-73521.

23 Daniel W. Drezner, “Targeted Sanctions in a World of Global Finance,” International Interactions 41, no. 4 (2015): 755–764.

24 Dursun Peksen and A. Cooper Drury, “Coercive or Corrosive: The Negative Impact of Economic Sanctions on Democracy,” International Interactions 36, no. 3 (2010), https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/03050629.2010.502436.

25 Narges Bajoghli, “Trump’s Iran Strategy Will Fail. Here’s Why,” New York Times, June 30, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/30/opinion/trump-iran-revolutionary-guards.html.

26 Thomas Schelling, Arms and Influence (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1966).

27 Dursun Peksen, “When Do Economic Sanctions Work Best?,” Center for a New American Security, June 10, 2019, https://www.cnas.org/publications/commentary/when-do-economic-sanctions-work-best; Jonathan Masters, “What Are Economic Sanctions?,” Council on Foreign Relations, August 12, 2019, https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/what-are-economic-sanctions#chapter-title-0-8; Gary Clyde Hufbauer, “Trade as a Weapon,” Peterson Institute for International Economics, April 12, 1999, https://piie.com/commentary/speeches-papers/trade-weapon.

28 David Cortright and George Lopez, Smart Sanctions: Targeting Economic Statecraft (Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2002), 8.

29 Drezner, “Targeted Sanctions in a World of Global Finance.”

30 Peter Feaver and Eric Lorber, “Understanding the Limits of Sanctions,” Lawfare, June 26, 2015, https://www.lawfareblog.com/understanding-limits-sanctions.

31 Feaver and Lorber, “Understanding the Limits of Sanctions.”

32 Natasha Turak, “Iran seizes foreign tanker in the Gulf, detains sailors, state TV says,” CNBC, August 4, 2019, https://www.cnbc.com/2019/08/04/iran-seizes-foreign-tanker-in-the-gulf-detains-sailors-state-tv-says.html.

33 Sharon Shi and Clément Bürge, “While Trump and Kim Talk, North Korea Appears to Expand Its Nuclear Arsenal,” Wall Street Journal, July 27, 2019, https://www.wsj.com/articles/while-trump-and-kim-talk-north-korea-appears-to-expand-its-nuclear-arsenal-11564059627.

34 Joel Schectman and Yeganeh Torbati, “New U.S. guidance on Iran sanctions seeks to reassure banks,” Reuters, October 10, 2016, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-iran-usa-sanctions-idUSKCN12A29Q.

35 Bozorgmehr Sharafedin, “Iran says European banks reluctant to resume transactions,” Reuters, March 5, 2016, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-iran-europe-banks-idUSKCN0W70OX; “Kerry and Zarif to meet again on Iranian sanctions relief,” Middle East Eye, April 21, 2016, https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/kerry-and-zarif-meet-again-iranian-sanctions-relief-1911411596.

36 Daniel W. Drezner, “Targeted Sanctions in a World of Global Finance,” International Interactions 41, no. 4, (2015): 755¬–764; Richard N. Haas, “Economic Sanctions: Too Much of a Bad Thing,” Brookings Institute, June 1, 1998, https://www.brookings.edu/research/economic-sanctions-too-much-of-a-bad-thing.

37 “Sanctions,” GovTrack, https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/subjects/sanctions/6232#_=.

38 Julie Ginsberg, “Reassessing the Jackson-Vanik Amendment,” Council on Foreign Relations, July 2, 2009, https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/reassessing-jackson-vanik-amendment.

39 Esfandyar Batmanghelidj and Nicholas Mulder, “Lifting Sanctions Isn’t as Simple as It Sounds,” Foreign Policy, April 15, 2019, https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/04/15/lifting-sanctions-isnt-as-simple-as-it-sounds-sudan-iran-bashir-rouhani-obama-trump-jcpoa-reconstruction.

40 Barry Eichengreen and Marc Flandreau, “The Rise and Fall of the Dollar (or when did the dollar replace sterling as the leading reserve currency?),” European Review of Economic History 13, no. 3, (December 2009): 377–411, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/european-review-of-economic-history/article/rise-and-fall-of-the-dollar-or-when-did-the-dollar-replace-sterling-as-the-leading-reserve-currency/9C78B88EBC0099E26A105DEC90CBE103; Peter Coy, “The Tyranny of the U.S. Dollar,” Bloomberg, October 3, 2018, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-10-03/the-tyranny-of-the-u-s-dollar.

41 “RMB Internationalization: Where we are and what we can expect in 2018,” SWIFT, January 2018, https://www.swift.com/resource/rmb-tracker-january-2018-special-report; Peter Coy, “The Tyranny of the U.S. Dollar,” Bloomberg, October 3, 2018, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-10-03/the-tyranny-of-the-u-s-dollar.

42 “Correspondent Banking,” Bank for International Settlements, July 2016, https://www.bis.org/cpmi/publ/d147.pdf.

43 Iñaki Aldasoro and Torsten Ehlers, “The Geography of Dollar Funding of non-US banks,” Bank of International Settlement, December 16, 2018, https://www.bis.org/publ/qtrpdf/r_qt1812b.htm.

44 Jim Woodsome, Vijaya Ramachandran, Clay Lowery, and Jody Myers, “Policy Responses to De-risking,” Center for Global Development, 2018, https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/policy-responses-de-risking.pdf; “A Crackdown on Financial Crime Means Global Banks Are Derisking,” Economist, July 8, 2017, https://www.economist.com/news/international/21724803-charities-and-poor-migrants-are-among-hardest-hit-crackdown-financial-crime-means.

45 Zachary Laub, “International Sanctions on Iran,” Council on Foreign Relations, July 15, 2015, https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/international-sanctions-iran.

46 Martin Arnold, “How US banks Took over the Financial World,” Financial Times, September 16, 2018, https://www.ft.com/content/6d9ba066-9eee-11e8-85da-eeb7a9ce36e4.

47 Masters, “What Are Economic Sanctions?”; Yalman Onaran, “Dollar Dominance Intact as U.S. Fines on Banks Raise Ire,” Bloomberg, July 16, 2014, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2014-07-15/dollar-dominance-intact-as-u-s-fines-on-banks-raise-ire.

48 Lynnley Browing, “Regulator Benjamin Lawsky Is the Man Banks Fear Most,” Newsweek, June 30, 2014, https://www.newsweek.com/regulator-benjamin-lawsky-man-banks-fear-most-256626.

49 Gary Richardson and Cathy Zhang, “Barry Eichengreen, Exorbitant Privilege. The Rise and Fall of the Dollar and the Future of the International Monetary System,” Oeconomia, 2013, https://journals.openedition.org/oeconomia/314; Thomas Palley, “Why Dollar Hegemony Is Unhealthy,” YaleGlobal Online, June 20, 2006, https://yaleglobal.yale.edu/content/why-dollar-hegemony-unhealthy.

50 Barry Eichengreen, “Global Imbalances and the Lessons of Bretton Woods,” NBER Working Paper No. 10497, May 2004, https://www.nber.org/papers/w10497.