Key Points

- Achieving greater European defensive autonomy is unlikely to be quick or easy. While there are alternatives, adapting NATO to this end is arguably the most realistic path.

- Pointing out the significant challenges to European defensive autonomy should not be construed as an endorsement of the status quo. Contending demands for limited U.S. military resources in Asia and elsewhere augur a reduced U.S. role in NATO regardless of Europe’s capacity to defend itself.

- Given current deficiencies with European capabilities and the failure of many NATO members to meet basic funding obligations, significant spending increases are likely needed to actualize greater independent European military capabilities.

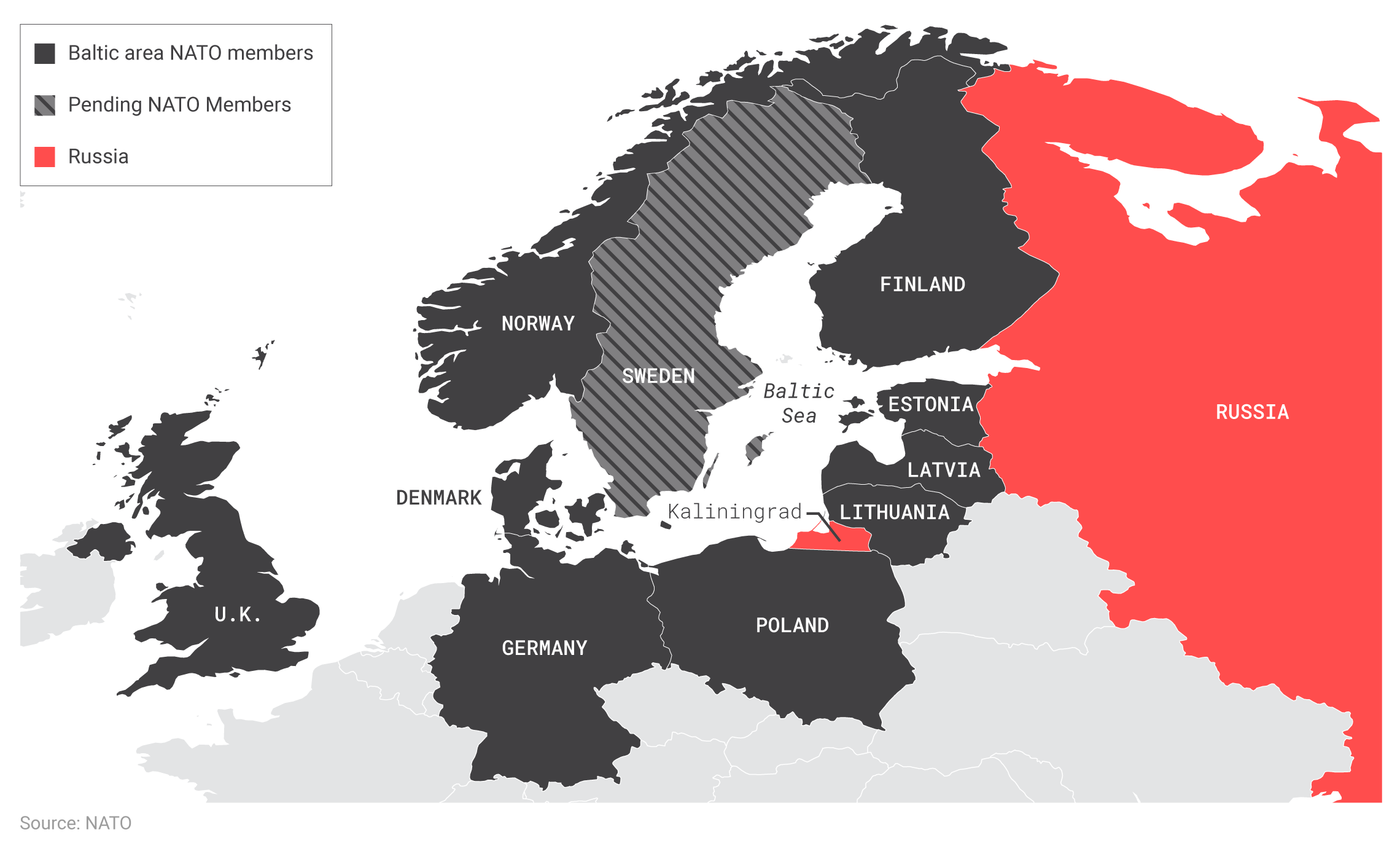

- Smaller coalitions within NATO could achieve more effective solutions at the regional level, as opposed to trying to achieve full defensive autonomy among all 29 European members. In particular, defense of the Nordic-Baltic region could be an important test case.

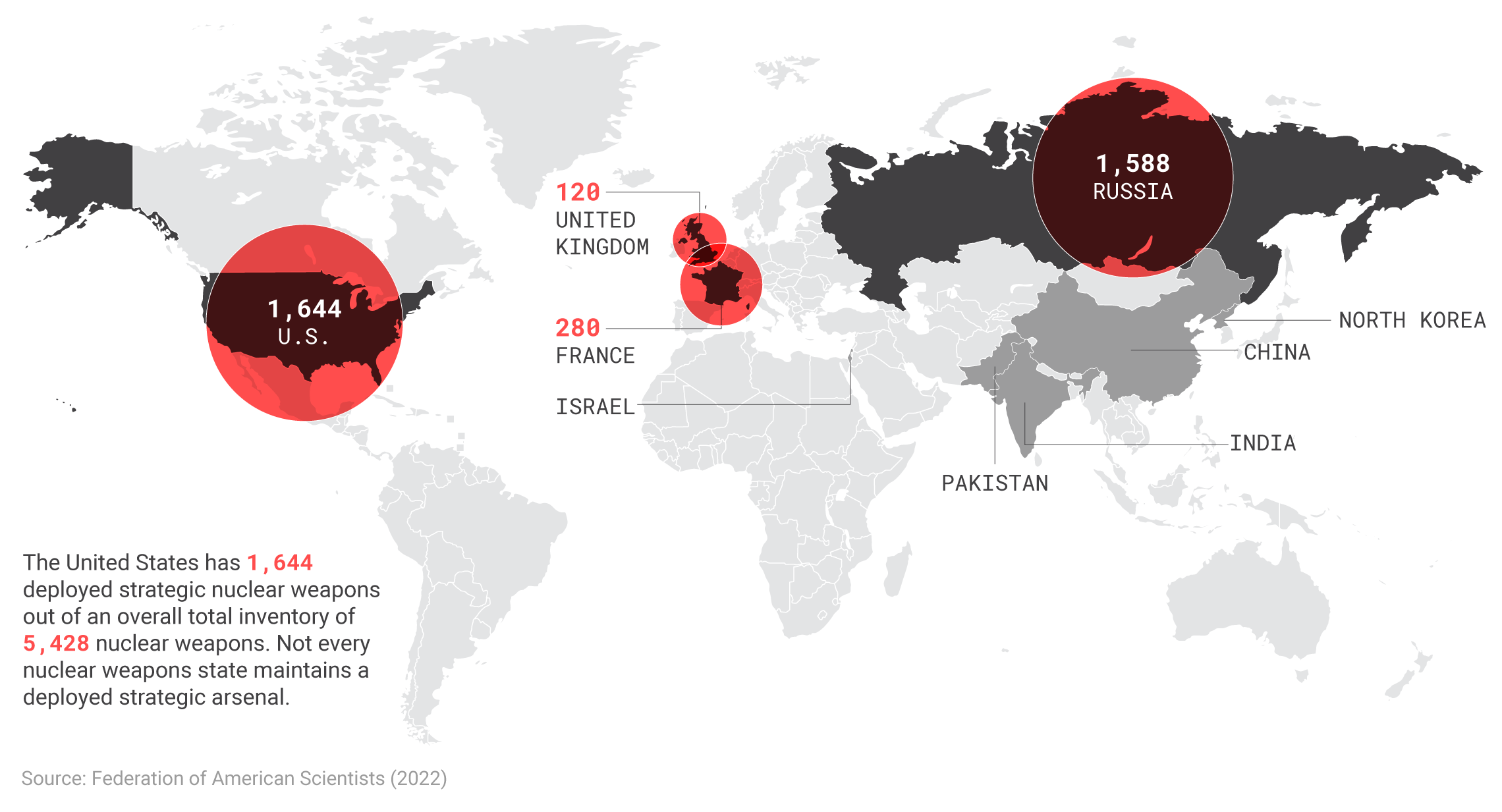

- Nuclear issues will be particularly difficult to navigate. Reliance on either British or French nuclear forces as NATO’s primary deterrent comes with important challenges. Likewise, retaining the U.S. nuclear umbrella absent U.S. ground forces in Europe could prove unworkable.

- Russia’s capacity to rebound long term and pose a more robust threat to Europe should not be discounted. This underscores the importance of working through the difficult issues associated with European defensive autonomy in the current strategic window of Russian weakness.1

Introduction

This paper is an exploration of issues that would need to be addressed to make greater European defensive autonomy a reality. It is not intended as an explicit argument in favor of the United States leaving NATO. Yet it needs to be acknowledged the United States might depart the alliance at some point. Even if it remains in NATO, U.S. contributions could be scaled back in the face of contending domestic priorities or competing demands for military resources in Asia.2 In either event, Europe would need to take up the primary burden for its defense. Realistic discussions of what that could look like in practice are therefore required.

The paper examines greater European defensive autonomy through the specific lens of NATO. While it is possible Europe could create a new security organization or try to employ the European Union (EU) to this end, building on the alliance’s established planning and command structures seems the more viable course.3 Focusing on NATO also accommodates a continuum of possible U.S. involvement in European security even as Europe assumes more direct responsibility for its own defense. This might seem contradictory, yet a truly clean break between the United States and Europe is unlikely. As will be discussed, the degree of cooperation between the two would be an important variable in how and when Europe assumes greater responsibility for its defense.

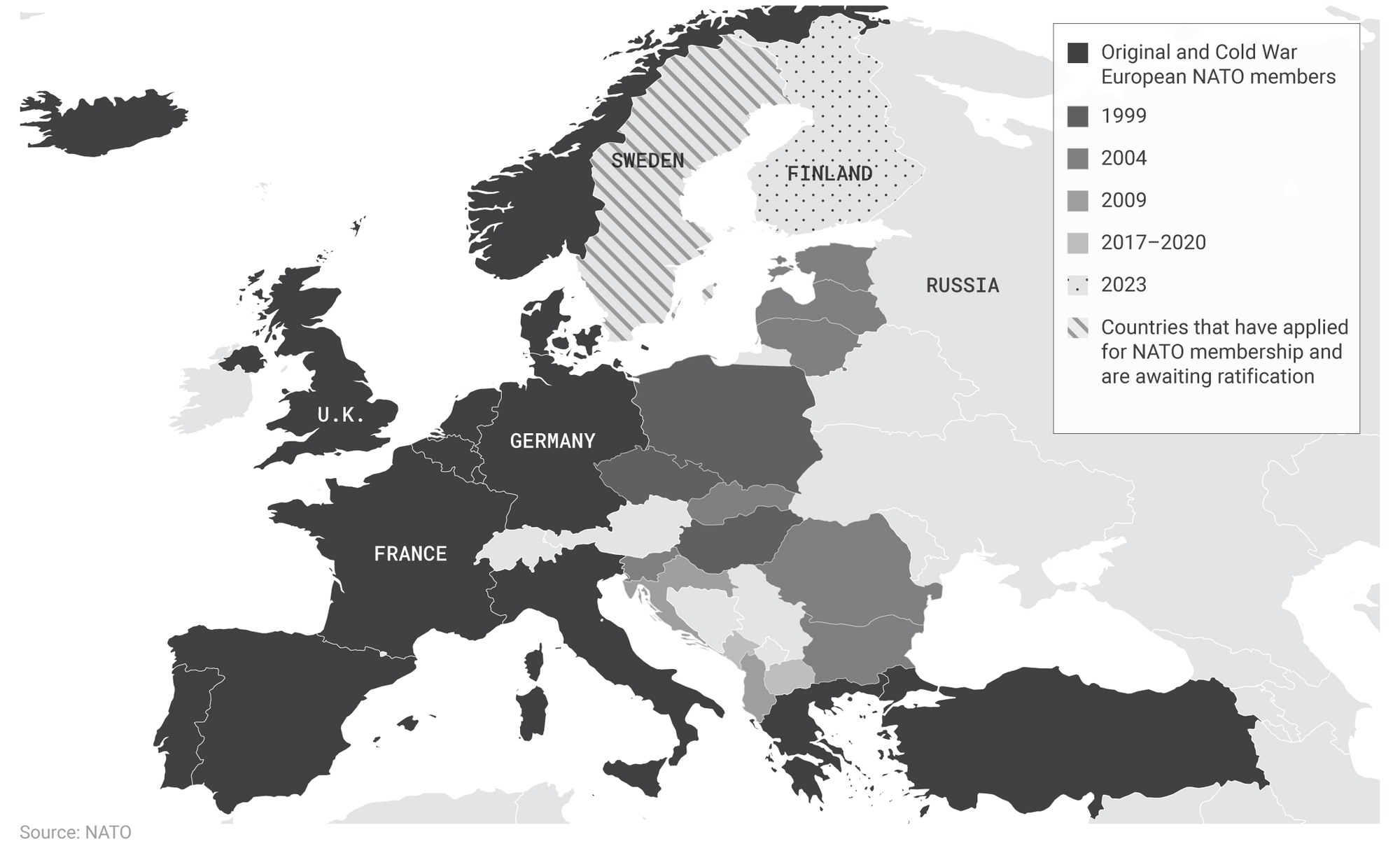

NATO THROUGH THE YEARS

The alliance could thus be retained absent formal U.S. participation or with a more limited role by the United States in deference to greater European capabilities. This paper allows for both possibilities. It begins with a brief overview of the extant literature on the question of whether Europe is able to defend itself. There follows an extended section examining defense funding and the shortcomings of existing European capabilities. The paper then proceeds to assess three other areas that could prove challenging with respect to greater European defensive autonomy: command relationships, C4ISR and interoperability,4 and nuclear forces. The paper concludes with some thoughts on the nature of the future Russian threat and the importance of the current strategic window for reassessing Europe’s contribution to its own defense.

If what follows is a critical analysis, it is not intended to endorse the status quo. Changes to the European security architecture are likely inevitable. The more honest we are about the difficulties of Europe assuming more responsibility for its own defense, the better the chances of overcoming those challenges.

The IISS-Posen debate

Prior to Russia’s mass invasion of eastern Ukraine, there was already a burgeoning scholarly debate over whether Europe was capable of providing its own defense absent a direct U.S. role. The discussion was initiated by an analysis published in April 2019 by a team of researchers at the International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS).5 Using scenario-based planning, they argued Europe was incapable of the task of self-defense. That paper sparked a 2020 article by MIT’s Barry Posen in the journal Survival, which rebutted the IISS assessment in favor of the viability of an autonomous European defense capability.6 Posen’s intervention, in turn, led to subsequent replies by the IISS team and additional scholars, including François Heisbourg, Stephen G. Brooks, and Hugo Meijer, as well as a final riposte by Posen, all of which appeared in a 2021 issue of Survival.7

To briefly summarize, the IISS analysis posited a scenario in which the United States suddenly withdrew from NATO.8 This was a step frequently discussed by former President Donald Trump and one which most legal analysts concede is within any U.S. president’s purview to take.9 Following the United States’ departure, the European members retain NATO, attempting to fill the gaps left by U.S. forces. However, faced with a Russian invasion of Lithuania and part of Poland, the Europeans are unable to mount an effective counterattack and liberate occupied allied territory.10 Among the many deficiencies emphasized by the IISS team are the poor readiness of European units, insufficient commonality of equipment, which impairs logistical support, and a general lack of armored forces for conducting offensive operations to retake territory.11

Posen countered that the IISS approach essentially predetermines its answers via choice of scenario. By forcing the Europeans to go on the offensive to liberate territory, it necessitates far more robust capabilities than other scenarios.12 Posen also objects to some of the IISS team’s forgiving assays of Russian readiness and argues factors like lack of commonality in European equipment can be overstated.13

Each analysis has its merits. The IISS team rightly demonstrates an abrupt U.S. withdrawal from NATO would be the worst of both worlds. Not only would this leave Europe unprepared to take over primary responsibility for its own defense, but also it would likely create significant challenges for U.S. force deployments—in Europe itself and in regions like Africa and the Middle East that depend upon the logistical bridge afforded by bases in Europe.14

For his part, though, Posen makes a case Europe could defend itself within reasonable parameters (i.e., defensive missions absent a strong offensive component). Indeed, it is hard to argue in the abstract that a region as rich and technologically advanced as Europe is not capable of providing for its own defense. But said wealth does not easily or automatically translate into an effective, unified defensive capability in reality. Here, analysts who argue for a quick transition to European defensive autonomy may be overly optimistic.

The U.S. vs. NATO-Europe vs. Russia along three common measures of power

Overall, the IISS-Posen debate is an important contribution because it puts forward the basic question of whether it is possible for Europe to defend itself, thereby opening the door for a follow-on conversation regarding the more salient question of how it could do so.

However, the discussion is also inherently Manichean. The analyses are structured in terms of a comparison between the current situation, where the United States is dominant in European security, and a potential future, where it is completely removed from the continent. More likely scenarios could entail some U.S. involvement along a continuum. For example, even if it was formally removed from the alliance, it is difficult to conjure scenarios where the United States would be completely neutral in the event of a Russian attack on either the Baltic states or Finland. At a minimum, the United States could provide intelligence support and munitions stocks (assuming they are available), as it has done for Ukraine.

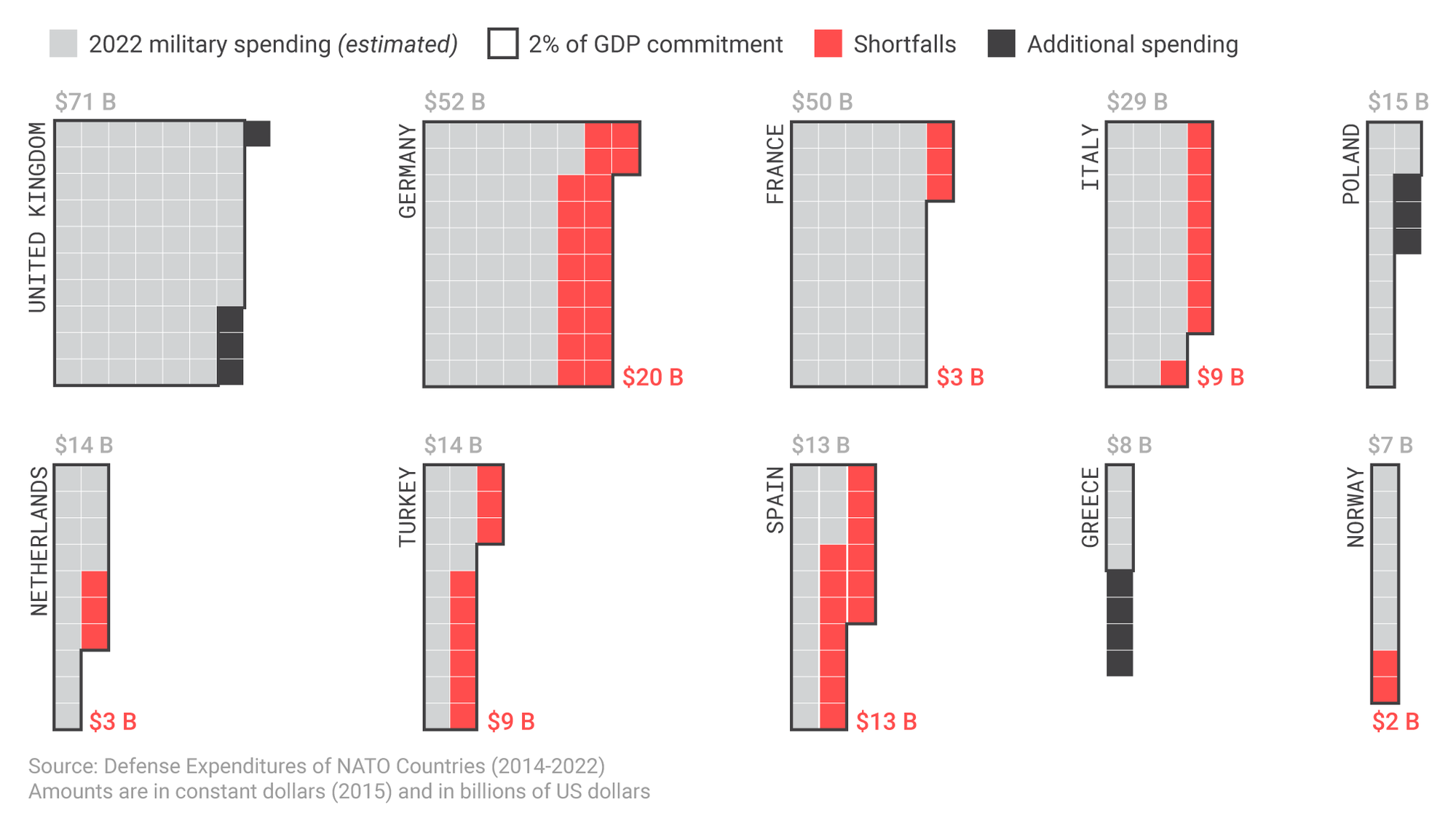

Funding

Yet such support also raises the prospect of continued overreliance by Europe on U.S. capabilities. If Europe didn’t feel it were truly on its own—if the prospect of a U.S. “rescue” were always in the background—how would it affect calculations regarding defense expenditures? Would Europe actually increase its defense spending if the United States pulls back or withdraws from NATO outright? Or would the Europeans continue to abjure difficult budgetary choices regarding their defensive needs? As will be discussed later, the issue of funding cuts to the heart of the viability of European defensive autonomy.

Burden shifting and the post-Vietnam era

But first, one historical precedent is worth exploring. In the late 1970s, the United States was able to reduce defense spending while European NATO members enhanced theirs. The Carter administration set forth goals for increased alliance capabilities and spending at the 1977 London meeting of the NATO Council. Excepting Iceland and Portugal, all European members of the alliance eventually increased defense spending, even as U.S. outlays declined (at constant prices). The result was that by 1980, the distribution of spending on defense between the United States and Europe reached its most equitable level of the Cold War, an approximately 56 percent to 44 percent split. These gains were short-lived, however. The onset of the Reagan administration and increased U.S. defense spending coincided with almost immediate decreases in European outlays.15

Estimates of NATO-Europe’s top 10 military spenders (2022)

Significantly, Carter never threatened troop withdrawals from Europe nor did he present NATO’s European members with a clear ultimatum on spending.16 However, he did table major U.S. defense programs—such as the B-1 bomber and the enhanced radiation weapon (or “neutron bomb”)—that could have played important roles in Europe’s defense.17 These steps arguably spoke louder than any overt threat the administration could have made about European spending, particularly when taken against the lingering backdrop of U.S. defeat in Vietnam.

It is interesting to consider the last time the United States was able to extract more equitable burden-sharing in NATO, it had just lost a major war in Asia. One wonders if legitimate concerns over doing so again could have a similar effect on European calculations now. If the United States made it clear it had other strategic priorities and unilaterally asserted it was adjusting its global defense posture accordingly, would that spur greater European defense outlays as U.S. capabilities receded?

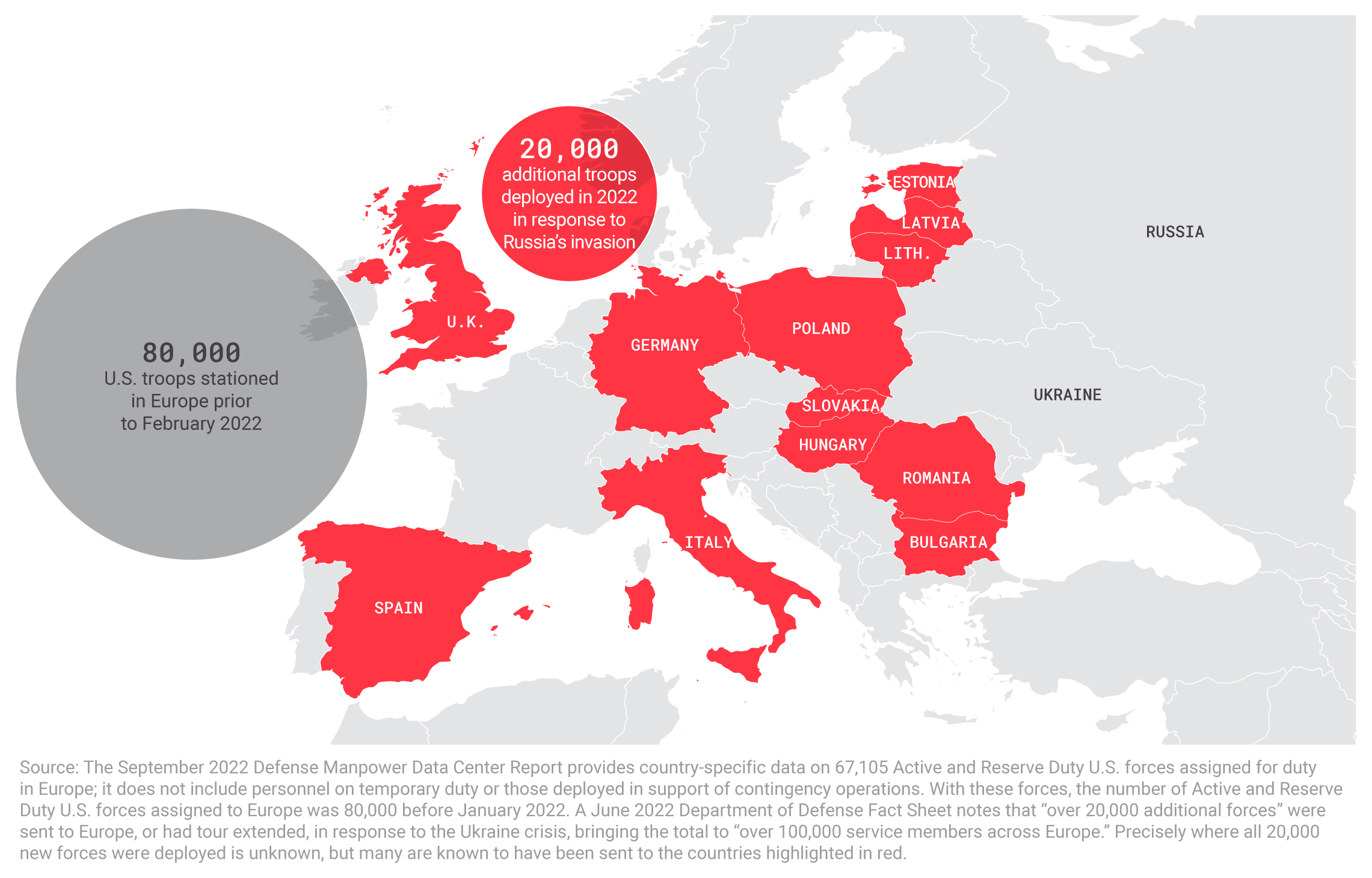

In contrast, greater U.S. force contributions to NATO seem to have the opposite effect in some cases. Already, for example, Germany appears to be modifying the ambitious funding commitments proffered after Russia’s assault on Ukraine.18 But this has occurred against the backdrop of the United States reinforcing its own capabilities in Europe. U.S. moves have included deploying an additional 20,000 troops to Europe, sending two additional squadrons of F-35s to Lakenheath airbase in the United Kingdom, permanently stationing V Corps headquarters in Poland, forward-basing two additional destroyers in Spain, and positioning a Brigade Combat Team in Romania.19

U.S. forces in Europe and post-February 2022 deployments

While this package of forces might have seemed prudent in the immediate wake of Russia’s mass invasion of eastern Ukraine, it now appears far less necessary. It is curious to act as if Russia is in danger of breaching the Vistula or the Elbe when it can scarcely cross the Dnieper.

More important to the issue at hand, U.S. reinforcements may have stymied momentum on spending increases in Europe, with the exception of a handful of countries. This is unfortunate, as European defensive autonomy is unlikely to be realized without significant increases in defense outlays across multiple states.

Major rivers in Central and Eastern Europe

Independent capabilities

Why are funding increases needed? French President Emmanuel Macron touched on the heart of the matter when he announced increases in his country’s future defense budgets in January 2023. President Macron said France needed to “repair” its armed forces then “transform” them, hinting at a two-phase process.20

“Repair” is the first step. Simply put, European capabilities are not what they should be in practice. In some cases, they constitute “a hollow force,” or one that lacks the manpower and equipment to execute its assigned missions. Consider this assessment of the United Kingdom’s sole armored division:

For many decades, we have not really delivered what we said on the tin . . . If I look on paper at the current armored division we have, it is lacking in all sorts of areas. It is lacking in deep fires, in medium-range air defense, in its electronic warfare and signals intelligence capability, in its modern digital and sensor-to-shooter capability. On top of that, it is probably lacking in weapons stocks.21

This analysis is damning for at least two reasons. First, it concerns a core combat capability of one of the European members of NATO that is generally regarded as taking its defense commitments seriously. Second, it comes from Ben Wallace, the sitting British Defense Minister. But Wallace’s remark in many ways embodies the problem that has long plagued NATO, particularly its European members—the gap between what capabilities look like on paper and what they actually constitute in reality.

Germany is among the worst offenders in this regard. Investments in basic military capabilities—secure radios, combat boots, cold weather gear—are needed to simply bring the Bundeswehr up to basic levels of competency.22 Also required, symbolically, is procurement of a standard-issue rifle that shoots straight, after the German military spent the last three decades with one that consistently lost accuracy at high rates of fire.23 Weapon shortages infamously forced some German troops to wield broomsticks during a 2014 exercise in Norway, an extraordinary step for soldiers of the world’s fourth largest economy.24

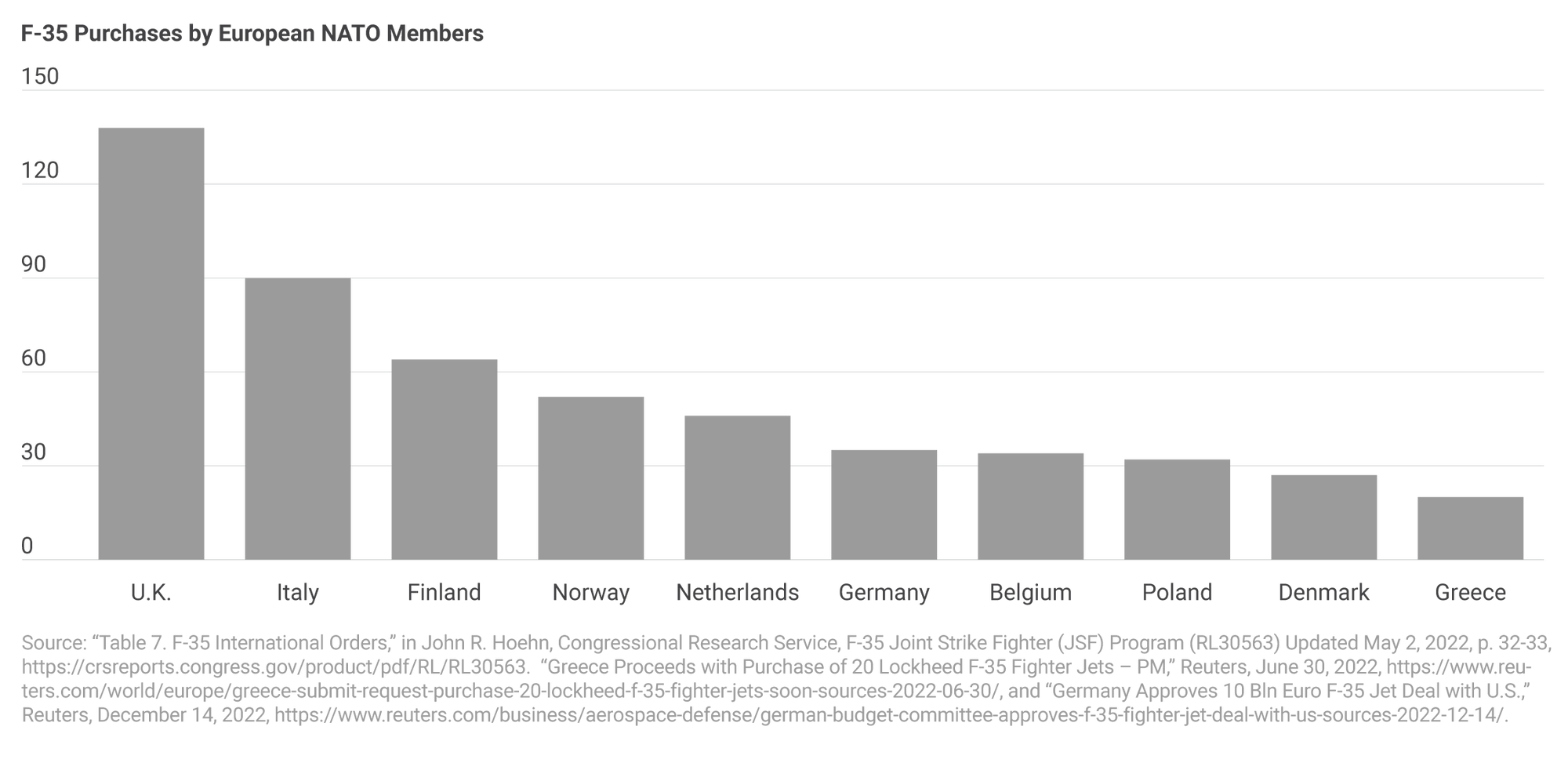

The need to rectify these fundamental shortages cuts into funding for more ambitious capabilities. For example, while Germany’s decision to acquire the F-35 is welcome, it is currently slated to buy only 35 aircraft or about half as many as Finland.25 (Or compare with Japan, the third largest economy, which is acquiring at least 105 F-35s and possibly as many as 147 for its defensive needs in the Pacific.)26 German readiness has also been hurt by design flaws in several of its domestically produced systems, including major problems with its next-generation frigate, the F-125, and its Puma infantry fighting vehicle, 18 copies of which broke down during a recent NATO exercise focused on rapid response.27

France itself has significant materiel problems, exacerbated by a broken maintenance system and spare parts shortages.28 A 2018 study revealed only one in three helicopters in the French armed forces were operational.29 The French military also has a curious shortage of some key combat systems. For example, it only fields 13 units of the multiple launch rocket system (MLRS), or 7 fewer than the United States has already transferred to Ukraine.30

Current proposed funding increases—be it those announced by President Macron in January, the German Zeitenwende, or the tentative British plan to hit 3 percent of GDP in defense spending—thus only serve the interests of baseline respectability, rather than underwriting a situation where Europe collectively fields real independent capabilities with a capacity for successful operations absent U.S. support.31 This is true even in the French case. Although President Macron correctly saw the need to first repair and then transform, it is unclear the proposed French funding increases will meet that latter objective. The increased outlays will also cover expanded military intelligence capabilities, undersea surveillance, and modernization of French nuclear forces.32 These are all important areas for French defense, but they will limit the monies available for recapitalizing French conventional forces.

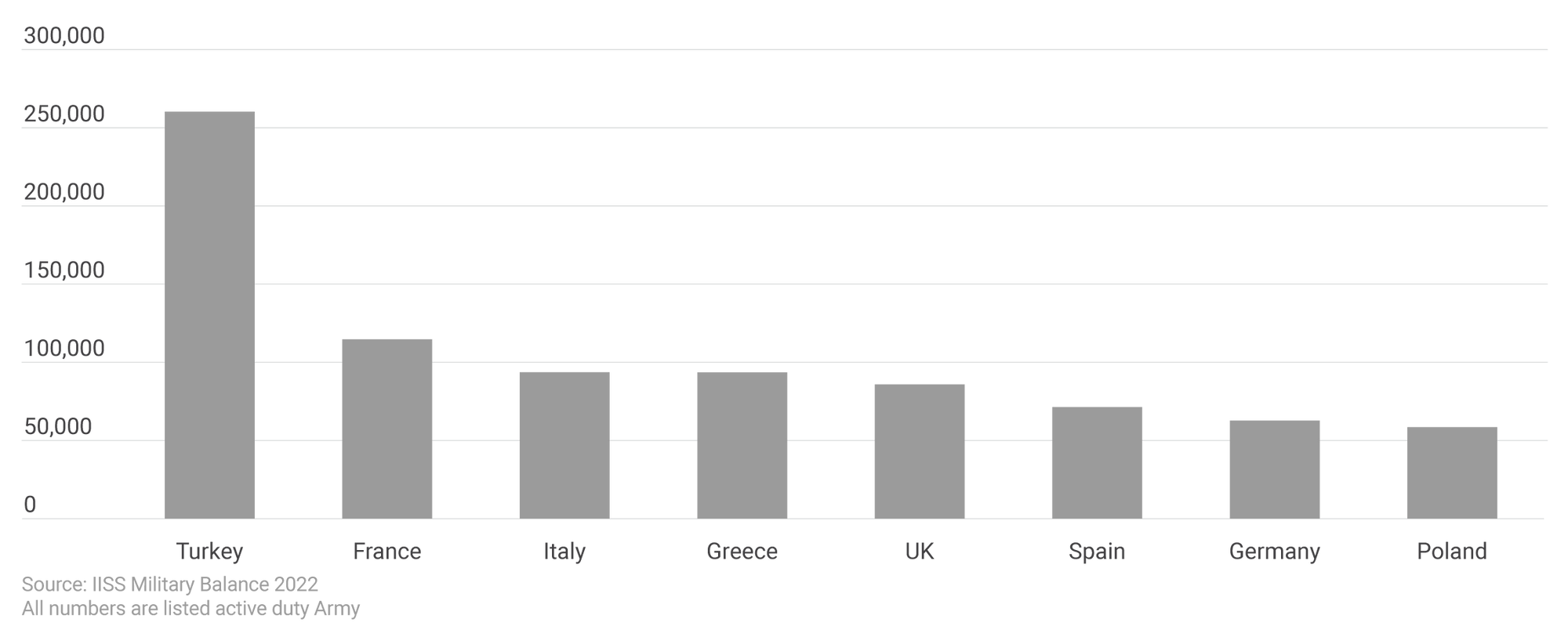

The return of mass

It is not empty chest-thumping to suggest U.S. military forces are substantially more relevant in NATO’s defense at this time than any one European state or even several states combined. It is not only a question of those U.S. forces actually on the ground in Europe—significant though they are—but also what assets the United States can flow into the theater from its own national stockpiles.

For example, open-source analyses suggest the U.S. Army’s goal is to have 12 combat brigades fighting in Europe within 3 months of an attack on NATO. This includes the two active brigades currently based in Europe, prepositioned equipment in Europe for another two, and eight brigades based in the United States.33 The 12 brigades the Army eventually would deploy constitute a considerable fighting force; no single European country could come close to matching it.

Indeed, given Defense Minister Wallace’s comments above, it is reasonable to question if the United Kingdom could send more than a single combat brigade. In the same testimony, Wallace observed that, at the time of the 1991 Gulf War, Britain was only able to deploy three brigades—two armored and one airborne assault—to help liberate Kuwait, instead of a full division.34 Given ensuing force reductions over the past 30 years, would the United Kingdom be able to match that now for a deployment in Central or Northern Europe? Could it generate two well-equipped combat brigades?

These types of questions are more relevant, as the Ukraine War has returned the concept of mass to discussions of modern warfare. Russia’s ability to absorb dizzying losses and remain in the field is one aspect driving this discussion; concerns that Ukraine lacks sufficient numbers of trained infantry to conduct additional counteroffensives is another. In either case, raw numbers seem to matter again, and this does not bode well for Europe’s major militaries.

The eight largest NATO-Europe Armies

Consider NATO’s eight largest armies after the United States (see chart). While they might appear impressive on paper, at least half are unlikely to make substantive contributions outside their own territory. By the far the biggest NATO European ground force belongs to Turkey. Yet Ankara’s troops are difficult to count on given the many differences between Turkey and its other European allies and the general independent bent of Turkish foreign policy under President Recep Tayyip Erdogan.35 Moreover, Turkey lacks power projection capabilities and traditionally has not been considered a direct player in conflicts in Central or Northern Europe. The same can be said of Greece even as it has begun exploring expeditionary operations by niche units, like its Patriot batteries.36 Italian forces are cordoned off from its allies to the north by the Alps, and the government of Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni has shown no signs of increasing defense spending beyond the current level of 1.5 percent of GDP.37 At best, Italy could contribute some air forces to a fight in Central or Northern Europe.38 Like Greece, Spain could send Patriots—as seen in its ongoing deployment of the missile defense system to Turkey—but its large standing army is confined to a territorial defense role.39

To put it simply, the Greek, Italian, Spanish, and Turkish armies might do a decent job of defending their home countries in the unlikely event Russia were somehow able to directly attack them with conventional forces. But those four armies might be of little relevance to a fight in, say, Estonia or Finland, despite their size. Those countries still might contribute some useful capabilities, like air defenses or a fighter squadron, but they are unlikely to make a difference with respect to strategic mass on the ground in Central or Northern Europe, where a direct clash between NATO and Russia is most likely.

That could change, of course, with major investments in strategic lift and other means for sustaining armies abroad for extended periods. But that, again, could only come about with major increases in funding, as well as a fundamental realignment in thinking on how those countries have operated their land forces since at least the end of World War II.

NATO's European core

Barring such a radical sea change, four other countries are left to form NATO’s European core: France, Germany, Poland, and the United Kingdom. Germany and Poland would be proximate to most future crises by virtue of their geographic position. France and the United Kingdom have some means to deploy forces beyond their own borders, but it is important to understand only a fraction of their total force might be available for forward-deployment to Central Europe.40 All four states could encounter major logistical difficulties sending substantial reinforcements to Finland.41

Basic markers—like number of main battle tanks (MBTs)—are also not encouraging. France, Germany, and the United Kingdom collectively field fewer tanks than Ukraine started the 2022 war with (slightly more than 800), although the western tanks are of better quality than Ukraine’s Soviet legacy systems.42 Poland is slightly more encouraging: It has almost 800 total MBTs, but the quality is also mixed, as the Polish army still relies on legacy systems such as the Soviet-designed T-72 for the bulk of its force with the rest of its inventory consisting of secondhand, Cold War-era platforms, like older models of the Leopard 2 tank.43 Poland is in the early stages of acquiring the M1A1 Abrams tanks, and this is an important development for NATO’s armored forces.44 At the same time, though, British plans call for slashing its tank force by one-third to just 148 upgraded Challenger 3 MBTs over the next few years.45

Estimated 2022 defense spending of NATO’s European members

By comparison, the U.S. Army now has 2,645 good-quality tanks in its active inventory with another 3,450 in reserve.46 As will be discussed, European inventories do not need to correspond with U.S. figures exactly to be effective at the regional level, but Europe still needs to do much more than simply “repair” its forces. NATO-Europe requires much more substantive capabilities, and that augmentation can only be attained with further spending increases by multiple states.

Signs of promise?

None of this is to completely doom-say the notion of European defensive autonomy. Indeed, it would be wrong to dismiss some of the extant capabilities of NATO’s European members. Perhaps most notable is Europe’s growing stock of F-35s. More through serendipity than coordinated planning, one-third of European NATO members are in the process of acquiring the stealth fighter. Once the individual national procurements are completed—likely by early next decade—more than 500 copies of the F-35 will be in service with NATO’s European members.47 This will significantly enhance interoperability and help standardize logistical support in one of the most critical areas of modern warfare: tactical air.48

F-35 purchases by NATO-Europe

NATO militaries in Europe also already field a number of sophisticated air defense systems. For example, four current members—Germany, Greece, the Netherlands, and Spain—operate Patriot, and the pending addition of Sweden to the alliance would make it five.49 Both Poland and Romania are in the early stages of acquiring Patriot as well, eventually giving NATO seven European members with some capability against theater ballistic missiles in addition to cruise missiles.50

The alliance would probably benefit from even more robust ballistic missile defense capabilities, like the U.S.-made Theater High Altitude Air Defense (THAAD) system or even the Israeli Arrow 3 missile defense system.51 Either would help protect the breadth of NATO territory against strikes from longer-range Russian systems employed either as terror tactics or to strike rear-area logistical nodes.

Still, even with existing capabilities, NATO’s European members are already better equipped in terms of air forces and air defenses than they are with respect to ground forces relative to Russia. Here, the importance of the Polish Abrams tank purchase should not be underestimated. Warsaw plans to eventually acquire 366 U.S.-made tanks in total, with the first copies to arrive this year.52 When completed, the Abrams buy will represent a significant armored capability based in a geographic area critical for Europe’s defense.

Coupled with its planned acquisition of the HIMARS version of the MLRS system, the F-35 stealth fighter, and Patriot, Poland isn’t just spending on its defense but appears to be spending well.53 Yet welcome as the Polish procurements are, they also bring up another potential issue for European defensive autonomy: overreliance on the United States as a munitions supplier.

Munitions supply and U.S. industrial base limitations

Issues related to munitions supply have already come to the fore because of the demands of the Ukraine War and are briefly worth recapping. According to some estimates, the United States has depleted its own supply of Javelin anti-tank missiles by 40 to 45 percent in an effort to meet Ukrainian demands for the weapon.54 It could take up to five years to replace those stocks.55 The United States has also reduced its reserve of 155 mm howitzer ammunition through transfers to Ukraine, perhaps dangerously so. According to one U.S. Department of Defense official, U.S. 155 mm ammunition stocks are now far below optimal levels if the United States needed to fight a war with its own forces.56

At the same time, NATO-Europe’s munition stocks are widely understood as threadbare. One analysis found Russia expended more ammunition in the Donbas over a 48-hour period than the United Kingdom had in its total national stockpile; at best, British reserves were thought to last a week in a high-intensity fight.57 In 2021, a senior French flag officer similarly confided to RAND analysts his own country wouldn’t be able to sustain a high-intensity fight for very long.58 A 2019 estimate suggested Germany might exhaust its ammunition stocks in as little as 72 hours; more recent reports caution munition reserves for some systems might not last a day.59 That is staggering. Finally, it is worth recalling that in the one instance where European members of NATO took the lead in a major operation—the 2011 intervention in Libya—they quickly ran out of precision-guided munitions.60

All of this points to a munitions problem with multiple and related layers. First, there are fundamental and longstanding issues with European munitions stocks. Second, the Ukraine War has exposed the limitations of the U.S. industrial base. This creates a third problem in which U.S. resupply might not be forthcoming if European militaries again run out of ammunition, particularly if the United States is concerned about its own ability to source a fight in the Pacific.

Dumb vs. smart munitions production

A fourth dimension of the problem can be thought of as “smart versus dumb.” Dumb ammunition, like 155 mm shells, is something that can probably be addressed solely with increased spending to build capacity and pay for more output. Even then, it will still take a few years to see results, and the scale of the challenge should not be underestimated. The U.S. Army recently invested $600 million in a plan that will result in U.S. manufacturers churning out 40,000 155 mm rounds per month by 2025.61 This monthly figure is still only comparable to what Russia fires every 48-hours in Ukraine.62

Smart systems are even more challenging. There are a limited number of factories that either produce key components for various U.S. missile systems or assemble the final product. The specialized nature of the work limits surge capacity. For example, a single Lockheed Martin facility in Camden, AR, manufactures the full suite of MLRS munitions (i.e., HIMARS, GMLRS, and ATACMS), as well as components for both Patriot and THAAD missile-defense interceptors.63 This places a hard cap on how many U.S. missile systems could be produced at any one time and raises unexpected concerns about purchases of U.S. systems by European militaries. Will there be enough “bullets” available for Patriot, HIMARS, and other advanced U.S.-made systems in Europe to shoot?64

Conceivably, additional manufacturing plants could be built for smart systems. It is even worth asking whether U.S. suppliers would sanction franchising a European factory to this end. But these are solutions that would likely take several years to implement given the sophistication of the systems being produced. There is no good, immediate answer here, but the dynamic of European dependency on U.S. munitions—and the limitations of the U.S. industrial base—is something that nonetheless needs to be understood when discussing the feasibility of European defensive autonomy.

Command relationships

At the risk of belaboring the point, the preceding discussion hopefully makes plain that European NATO members must increase defense spending in order to develop more robust, organic capabilities for Europe’s defense. But such capabilities might not be sufficient on their own. There also will be the matter of how Europe attempts to organize its disparate forces and what command arrangements it employs to pool its military power. These also could have important utility in situations where the United States remains in NATO but decreases its forces in Europe, handing off primary responsibility for specific defensive tasks in the process. Finally, there ideally could be synergy between assigning Europeans more direct responsibility for their defense at the regional level and encouraging increased defense outlays.

With that in mind, it is worth taking a moment to be clear on what NATO is and is not. Most importantly, it is not a supranational organization, like the European Union, with the ability to direct its members to take specific actions. Rather NATO operates entirely on consensus and bargaining with voluntary force contributions. For example, if the NATO commander, SACEUR,65 wanted to deploy a specific Italian battalion for a given task, he has no direct authority to do so. Instead, he needs to ask the Italian government, through its defense ministry, for permission. Rome can then say “Yes” or “No,” but is under no formal obligation to comply. There are instances where member states pre-designate forces to be available for specific NATO commands; SACEUR and other NATO commanders can more immediately access those units. Still, the preponderance of authority for employing force remains with national governments.66 “NATO” actually controls very few military assets directly.

NATO is thus perhaps best thought of as a standing military coalition rather than a rigid entity, albeit one with long established procedures and extensive organizational capacity for planning. The need for consensus and voluntary force contributions can, of course, work against military effectiveness. But it also gives the alliance a high degree of adaptability, one reason it has likely lasted for so long.67

Coalitions within NATO?

These considerations are relevant because they suggest the alliance could accommodate regional groupings in which select European members assume primary responsibility for specific defensive tasks.

Recall Posen’s point about choice of scenario and the general question, “Can Europe defend itself?” If the task is a continent-wide defense against a threat on the level of the Soviet Union at its peak, then the answer is, “No,” even with increased spending. But what if instead the problem is posed as, “Could a coalition of European NATO members defend the Baltic states or Finland from the reduced Russian threat that will emerge from the Ukraine War?” The answer then is likely to be “Yes”—if sufficient resource investments are made by the Europeans and regional planning duly integrated.68

To flesh out this idea, a “sub-NATO” consisting of Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Latvia, Lithuania, Norway, Poland, Sweden, and the United Kingdom would have primary responsibility for the Nordic-Baltic region. If each state enhanced its defense spending and committed appropriate forces, it seems reasonable they could manage the task of providing a sufficient defense of the Nordic-Baltic region against short- and mid-term threats from Russia, at least of a conventional nature. If further backed by additional contributions from France and a Germany that responsibly funded its military, prospects improve significantly.

Potential “sub-NATO” for the Nordic-Baltic region

Revisiting AFNORTH

The idea of such subgroupings being relevant to NATO is hardly new. Indeed, several smaller alliances and military pacts were important precursors to the Atlantic Alliance, as was the case with the Ogdensburg Agreement, signed between Canada and the United States in 1940, and the Brussels Pact, agreed in 1948 by Belgium, France, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom.69 In the post-Cold War world, regional groupings also formed important channels for cooperation, as in the case of the Visegrád Group (the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia).70

More formally, within NATO itself, regionalism provided the basis for allied commands throughout the Cold War. The original plan outlined by the alliance’s first SACEUR, Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, divided NATO territory and its surrounding seas into a series of geographic commands. On land, there were three: Allied Forces South (AFSOUTH), which, at the time, dealt primarily with Italy;71 Allied Forces Central (AFCENT), which focused on the bulk of Western Europe; and Allied Forces North (AFNORTH), which concerned Scandinavia.72

AFNORTH is worth dwelling on for a moment. It was arguably a secondary theater compared to AFCENT—where the main thrust of a Soviet attack was feared. But AFNORTH was unique among the three commands in that it was led by a European, a British admiral. Under him was a U.S. Air Force general, who served as the air component commander, and land commanders from Denmark and Norway overseeing ground forces in each of those countries.73 Eventually, an additional subordinate command was stood up under AFNORTH to guard the approaches to the Baltic Sea; it was led, on an alternating basis, by a Danish or West German general officer.74 Excepting air forces, AFNORTH was the one NATO command where the Europeans clearly dominated in terms of both force commitments and command positions.

NATO began to abandon its geographic-based command system in the 1990s; AFNORTH itself stood down in 1994. Eventually, the geographic command system was replaced entirely with two joint force commands (JFCs), based at Naples, Italy, and Brunssum, The Netherlands, and a joint force headquarters dedicated to maritime operations at Lisbon, Portugal.75 These changes, initiated at the 2002 NATO Summit in Prague, were intended to better attune the NATO command structure for the type of out-of-area operations which were seen as the alliance’s new priority in the wake of the 9/11 attacks.76

While the JFCs retain the ability to plan and execute territorial defense, it is but one of their competencies. Explicitly refocusing NATO’s command structure along geographic lines could underscore the alliance’s primary mission should again be defense of European territory. With an emphasis on defending their own borders, fewer forces from European member states would be available for out-of-area missions (where NATO’s track record is mixed, at best). This would obviate the main rationale for the JFC command structure. Instead, new geographic commands could be established in their place—perhaps one each focused on the Baltic Sea and Black Sea region—as a means of concentrating coalitions within NATO on specific, regional defensive missions.

In particular, a contemporary version of AFNORTH, with an all-European command structure, could be an important proof of concept for European defensive autonomy.77 If it can be made to work at the regional level in what is a major potential flashpoint with Russia, a modern-day AFNORTH would validate the basic idea of a European-led NATO. This could make all sides more comfortable with a genuine drawdown in U.S. forces in Europe at some future point.

A European SACEUR?

In closing this section, a word is needed about the potential for a European SACEUR in scenarios where the United States remains in the alliance. The position has always been held by an American with a European serving as deputy. As an American, SACEUR derives a significant element of their authority from being dual-hatted as the commander of U.S. European Command (EUCOM) and thus can directly control U.S. military assets in Europe, with the prospect of additional reinforcement from U.S. national reserves.78 Unless a European SACEUR had access to forces of comparable scale and quality, they are unlikely to carry the same weight in alliance circles, not least because they could only request to employ U.S. forces, instead of simply ordering it as in the case of an American SACEUR.

Using a European SACEUR as a forcing function for increased European focus on its own defense thus seems questionable, as has sometimes been suggested in policy debates.79 Rather it makes more sense for Europe to first field robust military forces and then present a candidate SACEUR capable of drawing on those capabilities. The approach outlined above—emphasizing European leadership on the regional level—would seem more advisable, at least in the near term.

Any scenarios where the United States retained its nuclear forces in Europe but assented to a European SACEUR could also raise difficult questions about the operational employment of those weapons. SACEUR is not the only—or even the final—decision-maker on alliance nuclear employment. But the position is nonetheless a critical voice in that process.80 Would the United States be willing to accept a European in that role given NATO’s tactical nuclear weapons—B61 air-delivered bombs—are ultimately U.S. national assets?81 This question points to the dilemmas that could arise if the United States drew down its conventional forces in Europe but left its nuclear umbrella in place through NATO. As discussed in more detail later, nuclear issues are among the most challenging when contemplating major changes to the U.S. role in European security.

C4ISR and interoperability

Another major challenge will be European NATO members’ ability to effectively pool and coordinate their military forces absent a direct role by the United States. Interoperability and C4ISR capabilities have long been NATO’s Achilles Heel even with strong U.S. involvement.

A cumbersome acronym, C4ISR encompasses “command, control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance.” It has been more succinctly described as a military’s “nervous system.”82 That is, C4ISR entails the systems through which military leaders—at various levels of command—employ their forces and the means by which the same leaders receive feedback on enemy movements and intentions. Roughly speaking, “C4” covers the control of forces while “ISR” the technical means of collecting information on the enemy.

The problem for NATO is its 31 members come to the table with heterogenous forces and equipment. While there are some commonalities in the systems fielded, there are inevitable divergences and idiosyncrasies across national militaries. This compromises the ability of military units and platforms to share data and effectively communicate across national lines. NATO’s diverse and expansive membership complicates the C4 picture considerably.

At the same time, U.S. intelligence collection assets dominate on the ISR side of the equation. This has repeatedly been seen in the Ukraine War, where U.S. intelligence accurately predicted the Russian invasion and has contributed important battlefield information to Kyiv since.83 As one of the more effective ripostes to Posen’s argument on European defensive autonomy points out, it would be extremely challenging for the alliance’s European members to replicate U.S. national ISR capabilities, particularly its space-based assets. Furthermore, this process could take two decades or more based on military satellite development timelines.84

NATO’s extant C4ISR capabilities

Still, there are important reasons to temper pessimism on European C4ISR capabilities. In the late 1970s, NATO initiated a collective purchase of 18 E3-A airborne warning and control (AWACS) aircraft, 14 of which are still in service.85 More recently, the alliance acquired five Phoenix high-altitude, long-endurance drones as part of its Alliance Ground Surveillance (AGS) initiative.86 The Phoenix is a version of the Global Hawk drone that still forms the backbone of the U.S. high-altitude drone fleet. The AWACS and Phoenixes are one instance where NATO actually fields its own forces as an alliance instead of relying on national contributions.

An obvious question is whether these assets are sufficient, especially if U.S. ISR contributions were removed or reduced. The answer is almost certainly, “No,” at least with respect to drones. For comparison’s sake, the U.S. Air Force alone is thought to have at least 45 to 50 high-altitude, long-endurance platforms in its unmanned fleet. This includes 30 Global Hawks and perhaps 15 to 20 copies of its classified RQ-170 and RQ-180 drones.87 These latter systems have stealth capabilities.88

Even if one considers the United States has global responsibilities requiring a far greater number of systems, five Phoenixes is likely too few for the whole of Europe. Doubling or tripling the AGS purchase seems a reasonable step to give NATO the core of a more robust unmanned capability. It is also worth considering a U.S. sale to NATO of a capability like the RQ-170. Although stealth remains one of the United States’ most carefully guarded military secrets, it has already crossed a line in terms of technology transfer with the sale of the F-35 stealth fighter to various European and Asian allies.89 Selling NATO a stealth drone could deepen the alliance’s ISR capabilities in important ways, including battlefield survivability.

NATO’s AWACS will also require replacement as they reach the end of their service lives around 2035.90 The point to emphasize here is improving NATO’s organic ISR capabilities is not a physical impossibility. Rather, it is a matter of political will and, as always, money.

It is worth reiterating U.S. support to NATO need not disappear entirely (as posited in the original IISS scenario). A reasonable division of labor can be suggested: alliance drones and AWACS supplemented by U.S. satellites and unique signals intelligence capabilities. This isn’t to encourage prolonged European dependency, but rather to emphasize Europe does not need to replicate all U.S. ISR capabilities. Such a task could, in fact, take decades and makes greater European defensive autonomy appear all the more elusive. More workable solutions are nearer at hand, at least with respect to ISR.

C4 integration

C4 integration remains more challenging. Fundamentally, the alliance is set up to fight in support of U.S. military power, not independent of it. Moreover, the United States doesn’t just provide NATO’s muscle in many cases, but also its sinew. Washington has been a leader in pushing for greater interoperability and has backed various initiatives to that end. The Bold Quest exercise series, funded by the Joint Staff, and the Maritime Theater Missile Defense (MTMD) Forum, in which the U.S. Navy figures prominently, are key examples.91 U.S. European Command also oversees and funds initiatives to promote greater technical integration specifically within Europe, while the U.S. Sixth Fleet at Naples plays a similar role among the alliance’s naval forces.92

That the United States would take such a lead is understandable: The more it can work effectively with allies at the regional level, theoretically, the better it can fight alongside them. The question for NATO is who would assume that leadership role if the United States pulled back from its alliance commitments or abrogated them entirely. As touched on earlier, France, Germany, Poland, and the United Kingdom would be the four key players in a NATO with reduced or no U.S. participation. But none of these emerges as an obvious first among equals, and there are significant differences between and among them.93

It is possible, though, C4 integration could proceed more smoothly within small coalitions inside NATO rather than across the alliance as a whole. For example, the head of the Royal Norwegian Air Force proposed establishing a Nordic Air Operations Center as a way to integrate air operations across Scandinavia with Finland now in the alliance and Sweden’s application pending. Conceivably, this could entail sharing of radar and sensor data in addition to coordinated mission planning.94 The Norwegian proposal could be an important test case, especially if it is instituted and fully funded by the Nordics themselves without direct U.S. involvement. (It would also dovetail nicely with the reemergence of an AFNORTH-like geographic command in NATO’s High North, as touched on above.)

Functional tasks—like maritime air and missile defense—can also be the basis for effective, small coalitions within the alliance. To date, the emphasis within the MTMD Forum has been on integrating individual allied ships with U.S. Navy battlegroups.95 But this need not be the sole focus moving forward. Greater European-to-European integration is certainly possible and is being explored.96 Even if only a half-dozen European navies achieve greater data sharing and sensor netting, that could still constitute an important allied capability absent a direct U.S. role. This would particularly be the case if it involved larger European navies, like the British and French fleets, both of which participate in the MTMD Forum.97 Interoperability within NATO need not be universal to be effective.

Overall, though, the difficulties of C4 integration without a strong U.S. lead should not be underestimated. It is one of the more challenging obstacles to European defensive autonomy. But small coalitions within NATO—both functional and geographic—can help bound the problem, as they do with respect to defense planning more generally.

Nuclear forces

A guiding assumption of this paper has been that a greater role for Europe in its own defense does not have to be a zero-sum game with respect to U.S. involvement. Whether it entails intelligence-sharing or other non-kinetic forms of support, there is a fair amount of middle ground between the current situation, where the United States leads decisively in European defense, and some future scenario, where all U.S. ties to NATO are severed. That said, questions related to the alliance’s nuclear forces complicate matters considerably.

Assume European members of NATO develop more robust conventional capabilities and take on primary responsibility for the defense of specific regions while the United States remains a member of the alliance. At some point, the viability of the U.S. nuclear umbrella would eventually need to be reexamined. One unspoken reason for keeping U.S. conventional combat power at the heart of NATO is it affords the United States primary control over military engagements short of nuclear employment. Removing U.S. combat power but leaving its nuclear guarantee in place outsources the conventional side of the equation to the Europeans—how and when they chose to fight could dictate if and when U.S. nuclear forces were required. This could be particularly problematic in either a Baltic or Finnish scenario, where there would be a high likelihood of NATO forces conducting conventional strikes against forces and facilities on Russian territory.

Would the United States stay in NATO under those circumstances? From the European side, would U.S. nuclear assurances still be considered valid if there were no or few U.S. ground forces left on the continent? This leads to a third, essential question: What measures could Europe take to field a viable nuclear deterrent on its own if the United States eventually left NATO?

Britain alone?

One obvious answer would be for British nuclear forces to assume a more prominent role in European nuclear deterrence. The United Kingdom already coordinates its nuclear planning with NATO through its Nuclear Planning Group (NPG), as does the United States.98 But numerically, British nuclear forces are simply not comparable to their American counterparts.

The U.S. strategic nuclear arsenal is estimated at about 5,428 warheads, although only 1,644 of these are believed to be deployed and operational.99 Still, that figure dwarfs the British arsenal of just 120 operational strategic warheads.100 These are deployed at sea, via a fleet of four Vanguard-class nuclear ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs.)101

Deployed strategic nuclear weapons

Would the United Kingdom’s comparatively small nuclear arsenal be sufficient to deter Russia on its own? Moscow possesses nuclear forces on the same scale as the United States, with an estimated 1,588 strategic warheads in operational service.102 Here, again, scenario selection is critical. If the question is whether British forces alone could deter Russian nuclear use in the event of a direct clash between NATO and Russian forces over Ukraine, the answer is almost certainly, “No.” On any matter of essential importance to Moscow, the size and scope of its nuclear forces will give it a trump card over London.103 Ukraine would clearly fit that definition.

But would that consideration apply in scenarios involving, say, the Baltic states or Finland? Then the answer becomes less clear. In a strictly defensive role, the United Kingdom’s small nuclear force could possibly be enough to give Russia pause. British SSBNs have a high degree of survivability, ensuring a second strike even if Russia were to launch a devastating initial attack. All 4 submarines in the Vanguard-class would not be deployed at the same time, but even 1 is believed to carry about 40 warheads.104 That would be more than sufficient to assure destruction of Moscow and select other Russian cities. Would that be enough to deter a Russian leader where a vital Russian interest were not considered to be at stake?

It is worth noting here that, were British nuclear forces to become NATO’s primary deterrent, the United States still would not be entirely removed from the equation. Foremost, the Trident D-5 missiles carried by the British Vanguards are drawn from a shared pool with the United States; under a somewhat convoluted arrangement, London has title to 58 Trident missiles, but the D-5’s are manufactured and technically owned by the United States.105 Newly commissioned Royal Navy SSBNs first deploy unarmed to King’s Bay, Georgia, to receive their allotment of missiles and occasionally return them for maintenance.106 Both the United States and the United Kingdom are also designing a new warhead for the Trident. Officially, these designs are separate with some collaboration, but less charitable analyses suggest the British are simply copying the U.S. warhead design, which has been designated the W93.107

The British nuclear deterrent is thus reliant in several critical ways on U.S. support. It remains to be seen how or if any substantive change in U.S. involvement in European security would affect that relationship.

French credibility issues

French nuclear forces do not have the same concerns regarding their independence. They also are somewhat larger than the British arsenal, with an estimated total inventory of 290 warheads (with 280 deployed), the bulk of which also deploy on SSBNs.108 Rather, credibility is more the issue in the French case when considering extended deterrence in Europe, particularly through NATO.

Unlike London, Paris has eschewed cooperative nuclear planning with the alliance, even after France rejoined NATO’s integrated military command in 2009.109 France is the only NATO member that does not participate in the NPG.110 At times, France has presented its nuclear forces as an alternative to NATO’s U.S.-led nuclear umbrella. In February 2020, for example, President Macron suggested French nuclear forces could be at the core of “strategic autonomy,” i.e., a more independent European foreign and defense policy absent U.S. involvement.111 But after more than 50 years of operating its nuclear force solely as an independent national asset, would other European states deem French extended deterrence credible?

During the Ukraine War, President Macron has kept diplomatic channels open to Russian President Vladimir Putin, including a series of phone calls between the two leaders. While such action can be seen as necessary statecraft, it has also sparked a backlash in parts of Europe, with some of the harshest criticism coming from states in NATO’s east, most notably Poland.112 This leads to questions about the willingness of these and other NATO members to accept French leadership on a European nuclear deterrent. Well before the Ukraine War, one survey of Estonian and Latvian security officials found a preference for nuclear guarantees from the United States and the United Kingdom (in that order) rather than France.113 Of course, if U.S. nuclear weapons were no longer a consideration, regional calculations could change.

New nuclear powers?

It is also worth considering whether new nuclear powers could arise. For example, more than is sometimes recognized in the United States, Germany has engaged in an extended public discussion over a possible independent nuclear deterrent since the 2016 U.S. presidential election, although prevailing opinion remains opposed.114 Poland would also seem a possible candidate for nuclear forces.115 Such a step would be in keeping with the overall leadership role Poland has assumed in NATO’s east.

Of course, the preceding speculation needs to be tempered by realistic appraisals of the time, effort, and cost of developing nuclear weapons. Particularly if no assistance is forthcoming from an existing nuclear power, it would be a significant undertaking even for technologically advanced states like Germany and Poland. Moreover, the importance of survivable, reliable means of delivery should not be underestimated. Germany and Poland lack immediate access to the deep waters of the Atlantic, an important precondition for a viable SSBN program (which itself would be a major technological challenge). This would leave both states reliant on land-based delivery options—either aircraft or missiles—that have less assured survivability than sea-based forces.

In truth, were the United States to withdraw from NATO tomorrow, it would likely be a decade at least—and quite possibly longer—before any new state in Europe were able to field an effective, survivable nuclear deterrent. In the interregnum, the only option for nuclear protection in Europe would be either of its established nuclear powers—France or the United Kingdom.

The X factor: Russia 2040

In closing this discussion, it is worth emphasizing Europe faces a unique moment of opportunity. Russia will likely emerge from the Ukraine War a hobbled power, with limited conventional capabilities for threatening other states, at least in the near term. That window creates a safe strategic space in which more honest discussions about European defensive autonomy can take place.

Before the Ukraine War, Russia’s scope for offensive operations against NATO territory was realistically considered to be the Baltic states and perhaps the northeastern quadrant of Poland to the so-called Vistula-Wieprz line, named after the two rivers that bound the salient.116 Even that seems an overestimation in hindsight. Deep penetration of Polish territory was likely beyond Russia’s reach and will continue be so until major changes are made to its logistical capabilities for supporting ground attack.117 For at least the next decade, the main threat to allied territory—to the extent Russia can mount one—will be to the Baltic states and Finland.

It is against the confines of that limited Russian challenge that a more autonomous European defense is far more feasible. But what about the decade beyond? What could Russian military capabilities look like in 2035 or 2040?

As a great power, Russia has the potential to rebuild and reconstitute its military, although this will require both time and perspective. A central variable will be the capacity of the Russian defense industry and how isolated it is from foreign parts and technology moving forward. Equally critical will be Russia’s ability to learn and adapt from its mistakes—something it was incorrectly believed to have done following its lumbering performance in its brief 2008 war with Georgia.118

Still, there are numerous examples of a great power rebounding from major defeats to later emerge with more robust and capable forces. The most infamous example is nonetheless worth restating: It took Germany just two decades to go from crushing defeat in World War I to the military juggernaut of the late 1930s. The United States itself needed fewer than 20 years to replace ignominious withdrawal from Vietnam in 1973 with a transformative performance in the 1991 Gulf War. It would be foolish to assume Russia could not reconstitute itself into a more effective military power given time. As two informed observers have noted, Russia is “down but not out.”119

A 20-year imperative

Looking at a potentially resurgent Russia along a 20-year horizon corresponds with China’s own declared goal for completing its long-term program of military modernization.120 Concerns in Asia are unlikely to abate as a strategic counterbalance to U.S. interests in Europe. And there remains the prospect of the United States fighting a major war in the Pacific during the interim, one that could significantly deplete its conventional capabilities even if it were to prevail.121 This reiterates the necessity of looking at the current strategic setting in Europe as a unique window.

If greater European defensive autonomy cannot be attained during a period of comparative Russian weakness, prospects for doing so if Russia renews its military strength seem even dimmer. This paper has suggested ways to adapt NATO to that end. But the alliance need not be the only pathway. The imperative, though, is to begin identifying and working through realistic steps—regardless of the specific mechanism employed—to enhance Europe’s role in its own defense now, while there is room for adaptation (and error). Increasingly, then, the discussion over European defensive autonomy must dwell on the question of “how,” not simply “if.”

This paper suggests some general notions to that end: Increased European defense spending is a prerequisite for even considering the prospect of greater European defensive autonomy. Future U.S. participation in European security does not necessarily need to be seen in zero-sum terms. Smaller coalitions within NATO might be able to move the ball further on defensive autonomy rather than waiting for all 29 European members of NATO to be in sync. The Nordic-Baltic region emerges as an important test case and likely would benefit from re-establishing a geographic command structure in NATO. ISR might present more ready solutions (through the acquisition of more high-endurance, long-range drones) as opposed to the difficulty of C4 integration across the alliance. Nuclear matters present no easy answers.

But these conclusions only begin to limn the many problems implementing European defensive autonomy involves. In general, this is a conversation that will not be easy or simple. It is worth repeating the premise voiced in the introduction: Unless there are realistic discussions of the problems European defensive autonomy could entail, those obstacles will never be surmounted.

Endnotes

1 Russian “weakness” is intended to convey the state of Russia’s capacity to threaten NATO-Europe directly at this time. It is not meant to undervalue the damage Russia has done in Ukraine. Indeed, while the efficacy of Russia’s invasion can be questioned, its cruelty and destructiveness should not be. Rather, the point here is Russian forces have already suffered remarkable losses, are still mired in a grinding war in southern and eastern Ukraine, and have little prospect of extracting themselves from said conflict anytime soon. This results in a much-decreased threat to NATO-Europe for the immediate future, even as it continues to exact a terrible price on Ukraine itself.

2 To date, the debate over U.S. strategic interests and force availability has largely been framed in terms of “Asia vs. Europe.” Less discussed are the significant force deployments the United States still maintains in the Middle East to uncertain effect. See David Blagden and Patrick Porter, “Desert Shield of the Republic? A Realist Case for Abandoning the Middle East,” Security Studies 30, no. 1 (2021): 5–48, https://doi.org/10.1080/09636412.2021.1885727.

3 The mutual defense clause of the Treaty of European Union (as amended by the Lisbon Treaty) explicitly defers to NATO on hard security concerns in the case of EU states with membership in both organizations. That is, NATO takes precedence in their defense. And with Sweden’s impending admission into the alliance, only four of the EU’s 27 states will be outside NATO: Austria, Cyprus, Ireland, and Malta. See Robert Bell, “The War in Ukraine, the Strategic Compass, and the Debate over EU Strategic Autonomy,” The Alphen Group, August 9, 2022, https://thealphengroup.com/2022/08/09/the-war-in-ukraine-the-strategic-compassand-the-debate-over-eu-strategic-autonomy/; Article 42.7 in “The Consolidated Treaty of European Union,” The Official Journal of the European Union, October 26, 2012, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:2bf140bf-a3f8-4ab2-b506-fd71826e6da6.0023.02/DOC_1&format=PDF.

4 C4ISR stands for “command, control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance.”

5 Douglas Barrie et al., “Defending Europe: Scenario-based Capability Requirements for NATO’s European Members,” International Institute for Strategic Studies, April 2019, https://www.iiss.org/blogs/research-paper/2019/05/defending-europe.

6 Barry R. Posen “Europe Can Defend Itself,” Survival 62, no. 6 (2020): 7-34, https://doi.org/10.1080/00396338.2020.1851080.

7 Douglas Barrie et al., “Europe’s Defense Requires Offense,” Survival 63, no. 1 (2021): 19-24, https://doi.org/10.1080/00396338.2021.1881249; François Heisbourg, “Europe Can Afford the Cost of Autonomy,” Survival 63, no. 1 (2021): 25-32, https://doi.org/10.1080/00396338.2021.1881250; Stephen G. Brooks & Hugo Meijer, “Europe Cannot Defend Itself: The Challenge of Pooling Military Power,” Survival 63, no. 1 (2021): 33-40, https://doi.org/10.1080/00396338.2021.1881251; Barry R. Posen, “In Reply: To Repeat, Europe Can Defend Itself,” Survival 63, no. 1 (2021): 41-49, https://doi.org/10.1080/00396338.2021.1881252.

8 Barrie, “Defending Europe,” 5.

9 Scott R. Anderson, “Saving NATO,” Lawfare, July 25, 2018, https://www.lawfareblog.com/saving-nato.

10 Barrie, “Defending Europe,” 15–34.

11 Barrie, “Defending Europe,” 4–5.

12 Posen, “Europe Can Defend Itself,” 12–13.

13 Posen, “Europe Can Defend Itself,” 13–22.

14 Alexander Lanoszka and Luis Simón, “A Military Drawdown in Germany? U.S. Force Posture in Europe from Trump to Biden,” The Washington Quarterly 44, no. 1 (Spring 2021): 206, https://doi.org/10.1080/0163660X.2021.1894718.

15 Wallace J. Thies, Friendly Rivals: Bargaining and Burden-Shifting in NATO (Armonk: M.E. Sharpe, 2003), 181–183, 202. Carter would likely have also increased defense spending substantially had he been re-elected, as shown by his proposed 1981 budget. George C. Wilson, “Carter Is Converted To a Big Spender On Defense Projects,” Washington Post, January 29, 1980, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1980/01/29/carter-is-converted-to-a-big-spender-on-defense-projects/6a04fed3-ca48-433e-a972-cca13bdf83a0/.

16 Thies, Friendly Rivals, 181.

17 Drew Middleton, “NATO Views Carter Policies with Unease,” New York Times, May 9, 1978, https://www.nytimes.com/1978/05/09/archives/nato-views-carter-policies-with-unease-military-analysis-bomber-and.html.

18 Alexander Luck, “Does ‘Zeitenwende’ Represent a Flash in the Pan or Renewal for the German Military?” Foreign Policy Research Institute, June 27, 2022, https://www.fpri.org/article/2022/06/does-zeitenwende-represent-a-flash-in-the-pan-or-renewal-for-the-german-military/.

19 “FACT SHEET—U.S. Defense Contributions to Europe,” U.S. Department of Defense, June 29, 2022, https://www.defense.gov/News/Releases/Release/Article/3078056/fact-sheet-us-defense-contributions-to-europe/.

20 Vivienne Machi, “Macron Wants €400 Billion to ‘Transform’ France’s Forces through 2030,” Defense News, January 20, 2023, https://www.defensenews.com/global/europe/2023/01/20/macron-wants-400-billion-to-transform-frances-forces-through-2030/.

21 House of Lords, International Relations and Defence Committee, UK defence policy: from aspiration to reality? HL Paper 124, January 12, 2023, 29, https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld5803/ldselect/ldintrel/124/124.pdf.

22 Georg Löfflmann, “The German Army Has Bigger Problems than Funding,” Spectator, March 20, 2022, https://www.spectator.co.uk/article/more-money-won-t-turn-germany-s-army-into-a-credible-fighting-force/; Matthias Gebauer and Konstantin von Hammerstein, “An Examination of the Truly Dire State of Germany’s Military,” Spiegel International, January 17, 2023, https://www.spiegel.de/international/germany/the-bad-news-bundeswehr-an-examination-of-the-truly-dire-state-of-germany-s-military-a-df92eaaf-e3f9-464d-99a3-ef0c27dcc797.

23 Joseph Trevithick, “HK416 Finally Looks Set To Become Germany’s Next Service Rifle,” The Drive, December 16, 2022, https://www.thedrive.com/the-war-zone/the-hk416-finally-looks-set-to-be-germanys-next-standard-rifle.

24 Rick Noack, “Germany’s Army Is So Under-Equipped that It Used Broomsticks Instead of Machine Guns,” Washington Post, February 19, 2015, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2015/02/19/germanys-army-is-so-under-equipped-that-it-used-broomsticks-instead-of-machine-guns/.

25 See Table 7 in John R. Hoehn, F-35 Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) Program, CRS Report No. RL30563 (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, 2022), 32–33, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/RL/RL30563.

26 See Table 7 in Hoehn, F-35 Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) Program, 32–33.

27 Guy Chazan, “Germany Reassures Nato on Task Force after Equipment Failure,” Financial Times, December 19, 2022, https://www.ft.com/content/b4fd05ff-02a5-47a3-9b6f-82eb44067c38.

28 Stephanie Pezard, Michael Shurkin, and David Ochmanek, A Strong Ally Stretched Thin, (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2021): 35–37, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA231-1.html.

29 Dominique de Legge, “Le Parc d’Hélicoptères des Armées: Une Envolée des Coûts de Maintenance, Une Indisponibilité Chronique, des Efforts Qui Doivent Être Prolongés,” Sénat, July 11, 2018, as cited in Pezard, Shurkin, and Ochmanek, A Strong Ally Stretched Thin, 36.

30 Pezard, Shurkin, and Ochmanek, A Strong Ally Stretched Thin, 33; “Chapter Four: Europe,” The Military Balance (London: International Institute for Strategic Studies, 2022): 105, https://doi.org/10.1080/04597222.2021.1868793; and Michael R. Gordon and Gordon Lubold, “U.S. Altered HIMARS Rocket Launchers to Keep Ukraine from Firing Missiles into Russia,” Wall Street Journal, December 5, 2022, https://www.wsj.com/articles/u-s-altered-himars-rocket-launchers-to-keep-ukraine-from-firing-missiles-into-russia-11670214338.

31 The 3 percent commitment was made by the former government of Liz Truss but has yet to be officially endorsed by the new prime minister, Rishi Sunak. Tim Martin, “UK Delays Defense Spending Increase, Raising Fears 3% GDP Target Will Be Axed,” Breaking Defense, November 17, 2022, https://breakingdefense.com/2022/11/uk-delays-defense-spending-increase-raising-fears-3-gdp-target-will-be-axed/.

32 Machi, “Macron Wants €400 Billion.”

33 See Albin Aronsson et al., Western Military Capability in Northern Europe 2020 Part II: National Capabilities, (Stockholm, Sweden: Swedish Defense Research Agency, 2021): 152–153, https://www.foi.se/rest-api/report/FOI-R--5013--SE.

34 House of Lords, U.K. defence policy, 29.

35 See, for example, Asli Aydintasbas, “Turkey Will Not Return to the Western Fold,” Foreign Affairs, May 19, 2021, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/turkey/2021-05-19/turkey-will-not-return-western-fold; Kali Robinson, “Turkey’s Growing Foreign Policy Ambitions,” Council on Foreign Relations, Backgrounder, Updated August 24, 2022, https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/turkeys-growing-foreign-policy-ambitions.

36 Lefteris Papadimas, “Greece Signs Deal to Provide Saudi Arabia with Patriot Air Defense System,” Reuters, April 20, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/greece-signs-deal-provide-saudi-arabia-with-patriot-air-defence-system-2021-04-20/.

37 Tom Kington, “Italian Defense-Investment Hikes Appear to Taper Off,” Defense News, December 9, 2022, https://www.defensenews.com/global/europe/2022/12/09/italian-defense-investment-hikes-appear-to-taper-off/.

38 See Table 7 in Hoehn, F-35 Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) Program, 32–33.

39 “Spain Extends Patriot Deployment in Türkiye until June 2023,” Hurriyet, November 13, 2022, https://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/spain-extends-patriot-deployment-in-turkiye-until-june-2023-178480.

40 See, for example, Aronsson et al., Western Military Capability, 117–118; 133–135.

41 On the logistical challenges of reinforcing southern Finland, see Mike Sweeney, “Questions Concerning Finnish Membership in NATO,” Defense Priorities, June 29, 2022, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/questions-concerning-finnish-membership-in-nato.

42 “Chapter Four: Europe” and “Chapter Five: Russia and Eurasia,” The Military Balance (London: International Institute for Strategic Studies, 2022): 105, 109, 160, and 212, https://doi.org/10.1080/04597222.2022.2022930.

43 “Chapter Four: Europe,” The Military Balance, 135.

44 Jen Judson, “U.S. State Dept. Clears Sale to Abrams Tanks to Poland,” Defense News, December 7, 2022, https://www.defensenews.com/land/2022/12/07/us-state-dept-clears-sale-of-abrams-tanks-to-poland/.

45 Jonathan Beale, “British Army to Get 148 Challenger 3 Tanks in £800m Deal,” BBC News, May 7, 2021, https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-shropshire-57025266.

46 “Chapter Three: North America,” The Military Balance (London: International Institute for Strategic Studies, 2022): 50, https://doi.org/10.1080/04597222.2022.2022928.

47 See Table 7 in Hoehn, F-35 Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) Program, 32–33. That chart includes orders placed by eight European NATO members through 2021; in 2022, Greece and Germany also joined this group with orders for 20 and 35 aircraft, respectively. Renee Maltezou and Lefteris Papadimas, “Greece Proceeds with Purchase of 20 Lockheed F-35 Fighter Jets–PM,” Reuters, June 30, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/greece-submit-request-purchase-20-lockheed-f-35-fighter-jets-soon-sources-2022-06-30/; Sabine Siebold and Holger Hansen, “Germany Approves 10 Bln Euro F-35 Jet Deal with U.S.,” Reuters, December 14, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/business/aerospace-defense/german-budget-committee-approves-f-35-fighter-jet-deal-with-us-sources-2022-12-14/.

48 For preliminary efforts in this regard, see Tom Kington, “Users of the F-35 Huddle in Italy to Tout Joint Maintenance Plans,” Defense News, November 23, 2022, https://www.defensenews.com/global/europe/2022/11/23/users-of-the-f-35-huddle-in-italy-to-tout-joint-maintenance-plans/.

49 “Chapter Four: Europe,” The Military Balance, 111, 114, 131, 141, and 148.

50 Jen Judson, “It’s Official: Romania Signs Deal to Buy U.S. Missile Defense System,” Defense News, November 29, 2017, https://www.defensenews.com/land/2017/11/30/its-official-romania-signs-deal-to-buy-us-missile-defense-system/; Jen Judson, “Poland Officially Signs Deal to Buy Patriot from U.S.,” Defense News, March 28, 2018, https://www.defensenews.com/land/2018/03/28/poland-officially-signs-deal-to-buy-patriot-from-us/.

51 Reports appeared in the latter half of 2022 that Germany was considering an Arrow 3 purchase, but there has been no firm action to date. Thomas Newdick, “Germany Choosing Arrow 3 Missile Defense System Would Be A Big Deal,” The Drive, September 16, 2022, https://www.thedrive.com/the-war-zone/germany-choosing-arrow-3-missile-defense-system-would-be-a-big-deal; Aron Aronheim, “Defense Minister Benny Gantz Hopeful about Arrow-3 Sale to Germany,” Jerusalem Post, December 6, 2022, https://www.jpost.com/israel-news/article-724188.

52 Judson, “U.S. State Dept.”

53 Bartosz Głowacki, “Poland Moves to Buy HIMARS, Capping Major May Modernization Push,” Breaking Defense, June 6, 2022, https://breakingdefense.com/2022/06/poland-moves-to-buy-himars-capping-major-may-modernization-push/; Table 7 in Hoehn, F-35 Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) Program, 32–33; Judson, “Poland Officially Signs.”

54 Austin Dahmer, “Strategic Scarcity: Allocating Arms and Attention in Washington,” The National Interest, November 5, 2022, https://nationalinterest.org/feature/strategic-scarcity-allocating-arms-and-attention-washington-205726.

55 See comments by Ellen Lord, former Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment, in Hearing to Receive Testimony on the Health of the Defense Industrial Base, United States Senate, 117 Cong. 2 (2022), 25, https://www.armed-services.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/22-28_04-26-2022.pdf.

56 Gordon Lubold, Nancy A. Youssef, and Ben Kesling, “Ukraine War Is Depleting U.S. Ammunition Stockpiles, Sparking Pentagon Concern,” Wall Street Journal, August 29, 2022, https://www.wsj.com/articles/ukraine-war-depleting-u-s-ammunition-stockpiles-sparking-pentagon-concern-11661792188.

57 Mykhaylo Zabrodskyi et al., Preliminary Lessons in Conventional Warfighting from Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine: February–July 2022, Royal United Services Institute, November 30, 2022, 55, https://rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/special-resources/preliminary-lessons-conventional-warfighting-russias-invasion-ukraine-february-july-2022.

58 Pezard, Shurkin, and Ochmanek, A Strong Ally Stretched Thin, 38.

59 Löfflmann, “The German Army Has Bigger Problems than Funding;” Hans Von Der Burchard, “German Defense Minister Comes under Heavy Fire over Ammunition Shortages,” Politico, December 1, 2022, https://www.politico.eu/article/german-defense-ministerchristine-lambrecht-under-heavy-fire-over-ammunition-shortages/.

60 Karen DeYoung and Greg Jaffe, “NATO Runs Short on Some Munitions in Libya,” Washington Post, April 15, 2011, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/nato-runs-short-on-some-munitions-in-libya/2011/04/15/AF3O7ElD_story.html; Steve Erlanger, “Libya’s Dark Lesson,” New York Times, September 3, 2011, https://www.nytimes.com/2011/09/04/sunday-review/what-libyas-lessons-mean-for-nato.html.

61 See Sam Cranny-Evans, “Ramping Up: What Will It Take to Boost the UK’s Magazine Depth?” Royal United Services Institute, December 6, 2022, https://www.rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/commentary/ramping-what-will-it-take-boost-uks-magazine-depth; Joe Gould, “Army Plans ‘Dramatic’ Ammo Production Boost as Ukraine Drains Stocks,” Defense News, December 5, 2022, https://www.defensenews.com/pentagon/2022/12/05/army-plans-dramatic-ammo-production-boost-as-ukraine-drains-stocks/.

62 Jack Watling and Nick Reynolds, Ukraine at War: Paving the Road from Survival to Victory, Royal United Services Institute, July 4, 2022, 6, https://rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/special-resources/ukraine-war-paving-road-survival-victory.

63 See Dahmer, “Strategic Scarcity;” Bryan Bender, “The Struggling Arkansas Town That Helped Stop Russia in Its Tracks,” Politico, September 9, 2022, https://www.politico.com/news/magazine/2022/09/09/ukraine-war-arkansas-weapons-00055124; “Camden Operations is a Lockheed Martin Center of Excellence for Precision Fires and Ground Vehicle Production,” Lockheed Martin, accessed January 23, 2023, https://www.lockheedmartin.com/en-us/who-we-are/business-areas/missiles-and-fire-control/camden.html.

64 Cranny-Evans, “Ramping Up.”

65 SACEUR stands for “Supreme Allied Commander, Europe.” The term has its origins in World War II but was adopted in 1951 for use with NATO.

66 Dieter Krüger, “Institutionalizing NATO’s Military Bureaucracy: The Making of an Integrated Chain of Command,” in NATO’s Post-Cold War Politics: The Changing Provision of Security, ed. Sebastian Mayer (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014): 59–60.

67 See Wallace J. Thies, Why NATO Endures (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009): 287–307.

68 Both Posen and the IISS team are pessimistic regarding a European-led NATO’s ability to defend the Baltic states in their scenarios. However, they were writing prior to Russia’s 2022 invasion of eastern Ukraine and subsequent poor military performance. I also assume here that the alliance’s European members proceed with the level of increased funding for independent capabilities discussed in the first half of this paper.

69 Krüger, “Institutionalizing NATO’s Military Bureaucracy,” 50-52; Alexander Lanoszka, Military Alliances in the Twenty-First Century (Medford: Polity Press, 2022): 138.

70 Marcin Urbański and Karol Dołęga, “The Visegrad Group in the Western Security System,” Security & Defense Quarterly 9, no. 4 (2015) 5–37, https://doi.org/10.35467/sdq/103285.

71 AFSOUTH would eventually gain responsibility for Greece and Turkey as well once they joined the alliance in 1952.

72 Gregory W. Pedlow, “The Evolution of NATO’s Command Structure, 1951-2009,” North Atlantic Treaty Organization, 1, accessed September 1, 2022, https://shape.nato.int/resources/21/Evolution%20of%20NATO%20Cmd%20Structure%201951-2009.pdf.