The U.S. must find a way to co-exist with Russia to advance U.S. interests

Russia possesses the world’s largest nuclear arsenal, which poses an existential threat to the U.S. Avoiding escalation that could result in hostilities—and potentially nuclear war—remains the highest U.S. national security priority with respect to Russia.

While its behavior is often destabilizing, aggressive, and illiberal, U.S. analysts and decision makers can better predict and counter Russia’s foreign policies by understanding the logic of how it seeks to fulfill its core national interests, as it understands them.

Treating Russia as a perennial pariah makes advancing U.S. interests more difficult. Russia is a veto-wielding member of the U.N. Security Council. Its limited but potent regional power allows it to play spoiler and power broker on some issues tied to important U.S. interests.

Cyber hacks, misinformation, and espionage will remain a bone of contention between the U.S. and Russia. The U.S. has an interest in limiting these activities from Russia, but they are not a casus belli or a cause for great alarm.

U.S. interests should guide Russia policy, not an urge to dispense justice for its numerous sins. Inflating the threat Russia poses to the U.S.—or confusing its violations of liberal values with hard security interests—risks conflict that could go nuclear.

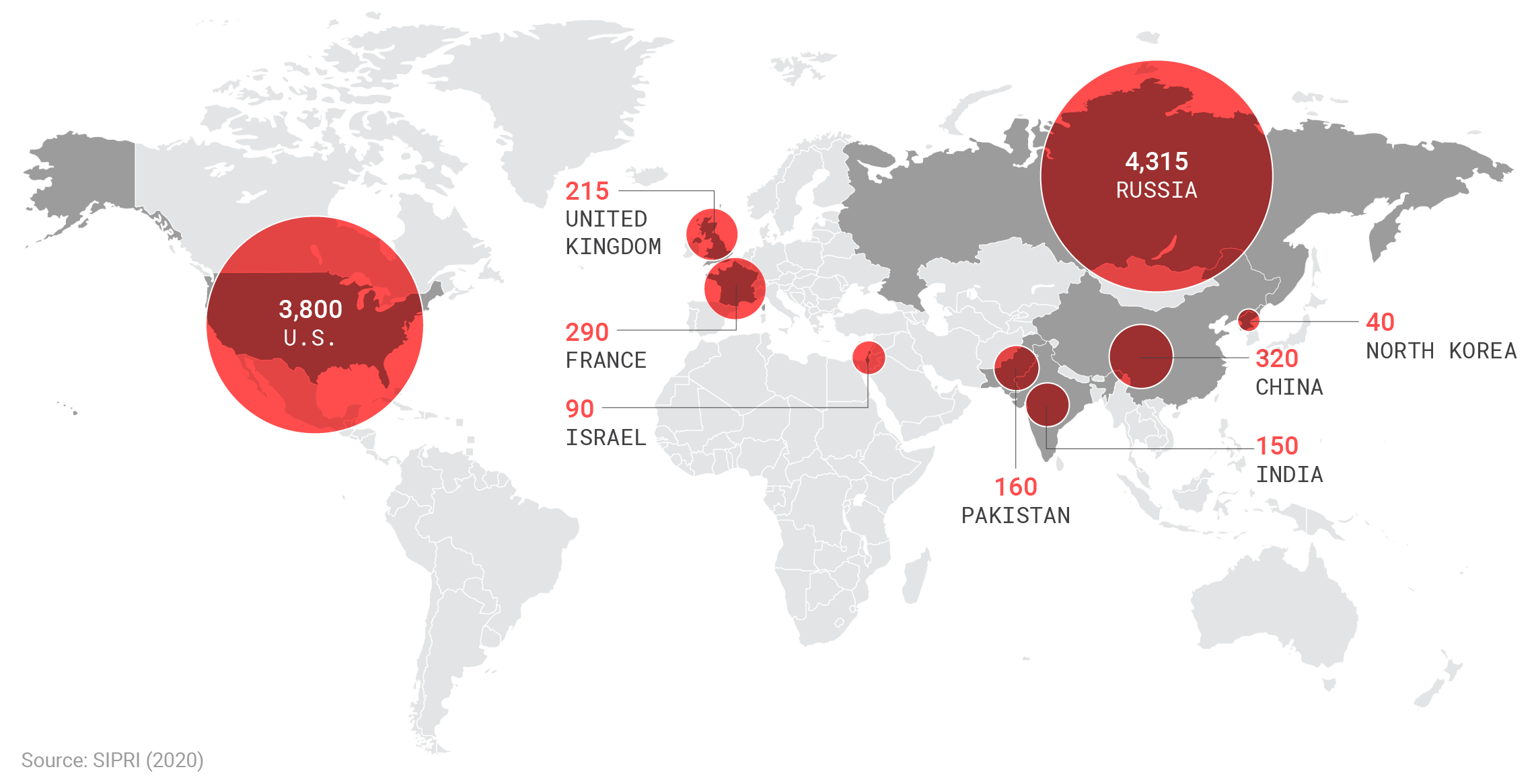

Number of nuclear weapons (deployed plus stored) by country

The U.S. and Russia account for nearly nine of every ten deployed or stored nuclear warheads in the world. Avoiding a nuclear conflict remains the highest U.S. national security priority with respect to Russia.

Assessing Russia’s power

NATO was formed for realist reasons: to prevent the USSR from dominating and organizing Europe, which would directly threaten the U.S. Russia is a shell of the former USSR and is now a regional power, not a potential Eurasian hegemon. Russia also has no major allies.

Internally, Russia confronts demographic decline and a sclerotic, hydrocarbon-dependent economy. Measured in purchasing power parity (PPP), Russia is projected to grow the slowest of any of the 10 largest economies in 2021, according to the IMF.

Russia fields a formidable military and spends the fourth most in the world on its forces, behind India and above Saudi Arabia. Since 2010, its annual spending has increased by 30 percent, a result of new investments after a problem-prone 2008 campaign in Georgia.

Russia’s economy is small compared to NATO-Europe’s. Russia’s $4.3 T (PPP) economy is about one-sixth of NATO-Europe’s ($25.4 T). This limits Russia’s threat, since economic prosperity is the foundation of military power.

Russia’s military spending is 3.9 percent of GDP compared with NATO-Europe’s 1.7 percent, a greater burden for Russia to sustain that also constrains other investments to modernize its economy and increase productivity, keys to growth.

Comparison of NATO-Europe and Russia’s economies and military spending

NATO-Europe’s economic power and annual military spending dwarf Russia’s. Combined, Germany and France alone significantly surpass Russia on both measurements, even before the other 26 NATO members in Europe are included.

Arguments for NATO-Europe—not the U.S.—doing more to confront Russia

NATO is a military alliance designed to defend against possible Russian aggression. Russia remains a threat, primarily to Eastern Europe, but NATO should reform to reflect the drastically shifted balance of power since the early Cold War.

Anchored by Western Europe, NATO-Europe alone can balance Russia’s threat. Germany, France, and the U.K. together—not including 25 other NATO-Europe members—spend more than double what Russia does on military power.

Fewer U.S. forces in Europe would encourage wealthy European allies to field modern military power and shift the burden of defending the continent to European taxpayers and servicemembers.

Europe taking primary responsibility for matching up against Russia militarily would serve U.S. interests by (1) allowing the U.S. to focus on higher priorities in East Asia and at home and (2) giving Washington greater space to improve relations with Moscow.

NATO should not continue to drift toward out-of-area operations. Deployments in the greater Middle East or naval patrols in East Asia would drain NATO’s capacity and distract from its core mission of defending Europe from Russian aggression.

Since the Cold War ended, NATO membership has nearly doubled, adding expensive U.S. defense liabilities. NATO enlargement reinforced Russia’s perceived vulnerability, undermining U.S.-Russia relations and thereby strategic stability.

While Ukraine is not a NATO ally, Russia’s recent threats to its sovereignty by building up troops on their shared border are vexing. However, the U.S. should be wary of further entanglement in the Ukraine conflict.

Russia shares a border with Ukraine and has core security interests at stake there—the U.S. does not. Russia will always care more about Ukraine. U.S. policy cannot change geography or this imbalance of will.

Washington should cease intimating that military support or protectorate status for Kyiv through NATO is forthcoming. The threat of future U.S. military help may only encourage Ukraine to avoid a negotiated settlement and Russia to attack, taking now what may be harder to take later.

Russia’s overseas meddling is a nuisance, not a security threat to the U.S.

Russia’s ability to project power far from its borders faces fiscal and logistical constraints. Its interventions in recent years are concentrated in poorly governed areas of little geopolitical significance—more a nuisance than a direct security threat to the U.S.

Russia can negatively impact U.S. preferences around the world. Its meddling in Ukraine, Syria, Libya, and Nagorno-Karabakh are reasons for the U.S. to work with Russia on solutions. Policies to ostracize Russia for its power projection may temporarily feel good but solve nothing.

In Syria, for humanitarian reasons, the U.S. should want a diplomatic resolution to the civil war. No arrangement is likely without Russian buy-in. So, confrontation with Russia over other issues can frustrate a settlement there.

Russia’s intervention in Libya’s civil war via mercenary forces is limited, but it means it has some say there. A diplomatic solution to Libya’s fratricidal violence depends in part upon Russia exercising its role as a power broker.

Sanctions on Russia cost the U.S. and make diplomacy more difficult

Russian security services suppress domestic Russia opposition. The poisoning of Sergei Skripal in the U.K. in 2018, the ongoing arrests of Russian protesters, the imprisonment of Alexei Navalny in 2021, and other actions are condemnable.

The U.S. has enacted economic sanctions on Russia to signal its disproval, but history demonstrates they will not likely change its behavior. The U.S. has little leverage to make Russia more democratic or improve the human rights situation there.

Sanctions can negatively impact the Russian economy but often harden the leadership’s position, invite retaliation from Russia, and undermine dialogue on higher priority issues, such as arms control.

Tit-for-tat exchanges of sanctions and diplomatic expulsions unnecessarily burden bilateral diplomacy. Critically, imposing sanctions threatens the U.S. dollar’s advantageous role as the world’s reserve currency.

In retaliation for sanctions, the Russian government often expels or curtails the work of Western-based NGOs that would otherwise be advocating for liberalization, reform, and civil society in Russia.

Recommendations for U.S. policy toward Russia

Arrest the decline of U.S.-Russia relations to reduce the risks of a nuclear conflict between the two countries, an overriding interest.

Stop the overuse of U.S. sanctions, which do not achieve concrete political outcomes and come at great cost and risk to the U.S. and the U.S. dollar. Sanctions attempting to stop the nearly complete Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline from Russia to Germany seem doomed to fail and alienate our European ally.

Continue the drawdown of U.S. forces in Europe, which will shift the burden for European security onto European allies, including in Eastern Europe.

Halt NATO expansion. Adding security dependents weakens the U.S. and the alliance, which operates on consensus. Adding Ukraine or Georgia should be out of the question given their contested and nearly indefensible borders and lack of security benefit.

Build on the extension of New START in early 2021 to explore more wide-ranging talks on strategic stability issues.

Withdraw Cold War-era B-61 gravity bombs from Europe, starting with Turkey (Incirlik Air Base), which would lower tensions with Russia without compromising U.S. warfighting capability.

Avoid policies that drive Russia and China closer together—or worse, encourage them to move toward an anti-U.S. alliance. China is a far greater strategic challenge than Russia.