Disentangling from Syria’s civil war

The case for U.S. military withdrawal

Benjamin H. Friedman and Justin Logan

May 29, 2019

Key points

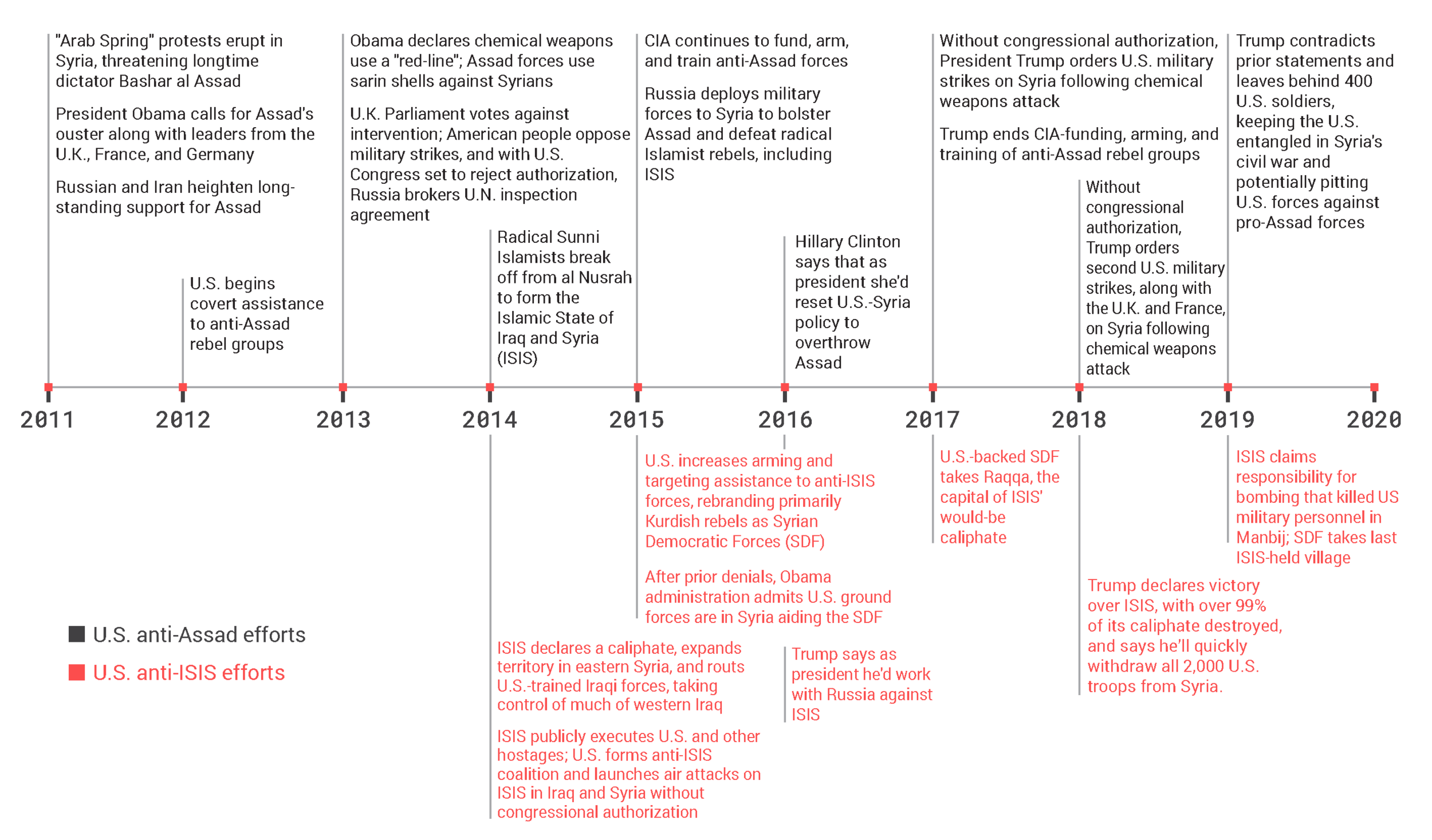

The United States intervened in Syria’s civil war in two ways: (1) anti-Assad efforts—through aid to rebels to help foster regime change and with airpower, troops and support to a militia—and (2) anti-ISIS efforts—through aid to the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) to destroy the Islamic State’s territorial caliphate. The first mission was an ill-considered failure, the second a success.

With the ISIS caliphate destroyed, U.S. troops have achieved all they reasonably can and should be fully withdrawn.

The best way to combat ISIS’s remnants, in the long-term, is to compel local actors take the lead in counterterrorism in Syria by removing U.S. forces, but retain the ability to monitor and strike terrorists from distance, given the need and proper legal authority.

The Assad regime, backed by Russia and Iran, has essentially won the civil war. Keeping U.S. forces in Syria creates needless risk of conflict with Syria, Russia, Iran, and even NATO ally Turkey.

Continuing U.S. military occupation of eastern Syria, which Congress never authorized, risks mission creep into indefinite efforts at nation building, which could increase U.S. war costs, give insurgents and terrorists opportunities to attack U.S. forces, tie down U.S. forces, and limit military readiness for core missions.

No outside power—including the United States—would benefit from occupying Syria and managing its civil war and post-war rebuilding. A continued Russian or Iranian presence in Syria does not threaten the U.S. or justify keeping U.S. forces there.

U.S. military withdrawal should not be contingent on negotiations, but the United States should push the Syrian government to limit humanitarian abuses and should support a deal restoring roughly pre-war conditions in eastern Syria: the Kurds keep their YPG militia but not autonomy; regime forces control the border, protecting the Kurds from Turkish forces; and both the YPG and Syrian government forces target surviving ISIS militants.

Overview

Removing U.S. forces from Syria’s civil war is the right policy. With the destruction of ISIS’s caliphate, U.S. military forces have accomplished all they can there. All that’s left are needless dangers: of escalation into war with Syria, Russia, Iran and its proxies, or even NATO ally Turkey; and of mission creep into an open-ended policing or nation-building campaign that allows various groups to target U.S. forces.

Several realities should inform U.S. policy in Syria.

1. U.S. forces in Syria have achieved what they reasonably can by denying ISIS territory.

Without its erstwhile “caliphate,” ISIS lost organizational capacity, as well as the mystique that fueled its emergence as the world’s leading terrorist brand and its recruiting success. Keeping U.S. forces in Syria to eliminate it as a terrorist entity or radical ideology is an invitation to stay forever—and failure.

Combatting ISIS, should it survive as a guerrilla or clandestine organization, is a poor mission to give U.S. military forces. A variety of actors in Syria are prepared to attack ISIS’s remnants: the Kurds of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), who did the bulk of the ground fighting against ISIS in Syria; Syrian government forces; the Iranians and their affiliated forces; the Russians; and even NATO ally Turkey.

This position does not forswear future U.S. strikes against some future threat from ISIS. The United States will retain the will and technical capability to strike from distance should local actors fall short. The point is instead that the United States does not need to be first in line to fight ISIS—in fact, U.S. ground forces may simply fuel the political resistance that ISIS needs to survive. The most realistic path to ISIS’s destruction is an end to the civil war.

Keeping troops in Syria—even a few hundred—to combat a post-territorial ISIS invites a broader nation-building campaign in an attempt to reform the politics that give rise to extremism in Syria’s Sunni community, something the United States has proven unable to do in Afghanistan, Iraq, and elsewhere. To an even larger degree than other recent U.S. wars of this sort, this mission would be severely undermanned and in clear opposition to the national government of the state. It would not only risk tying down U.S. forces in another failed effort that distracts from more important missions, but also risk an attack from Syrian forces that can overwhelm them or spark a wider war.

2. The array of outside powers pursuing varied interests in Syria’s civil war creates special dangers for U.S. forces.

Indefinitely backing the Kurds could bring conflict with Turkey. Israeli airstrikes against Iran and Iran-backed militia could draw U.S. forces rapidly into a wider conflict between those regional rivals. U.S. forces have reportedly clashed several times with Russian forces in Syria, risking escalation with a nuclear power. War with any one of these powers is possible, and policymakers should avoid even a low probability of dire consequences, especially when there is so little to gain.

3. The territory the U.S. military now occupies in Syria is not a prize that will benefit any outside power.

It is the Syrian government that is ultimately likely to rule there, not its Iranian or Russian backers. Even if Russia or Iran were to take over a swath of territory for a time, U.S. security would not suffer. There is little that outside powers can extract from Syria to enhance their power. As the civil war concludes, Syria’s meager oil revenue will flow mostly to Syria’s government, as it did before the war. Anyone trying to run part of Syria will be caught in a sectarian tinderbox, if not an outright civil war, and will pay for it. None could use Syria’s chaos to gain power, let alone propel itself to regional hegemony.

4. A U.S. military presence in Syria was not necessary to protect Syria’s Kurds before the civil war and is not necessary now.

It is true that the Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG militia) did most of the ground fighting against ISIS in Syria and a quick U.S. exit could expose them to attack by Turkey. That is why the United States should support (rather than block, as Washington is currently doing) the deal that the Kurds are pursuing—essentially to restore the status quo ante bellum—where Syrian government forces control Syria’s borders, and they operate at some distance from Turkey. The United States never signed up to protect an autonomous Kurdish statelet. That mission would keep U.S. forces engaged in an indefinite standoff or worse with Syrian and Turkish forces.

5. The Syrian government has essentially won the war.

The Syrian government has retaken most of densely populated western Syria, driven rebels into the northeast, and denied them any credible path to victory. The remaining non-jihadist rebels and the Kurds, who are not quite rebels, are all seeking a negotiated peace with the Syrian government.

The Assad regime has committed heinous crimes, including recurrent civilian massacres using bombs, chemical weapons, and missiles, and the widespread torture, rape, and murder of prisoners. But there was never a clearly superior alternative, even from a purely humanitarian perspective. The rebels were never poised to win, and if they had overthrown Assad, their disunity might have ushered in greater chaos and given a lasting role to jihadist groups. If a new government had managed to pacify the country, it would likely be one run by either Sunni extremists or a strongman that ruled similarly to Assad.

The liberal, unitary Syria that advocates of overthrowing Assad imagined was always a chimera. The way to minimize civilian harm now is to deal directly with Syria’s government and use what leverage the United States retains to push for decent treatment of civilians, the end of mass executions, the release of political prisoners, and amnesty or safe emigration for U.S.-backed rebels and anti-government activists.

This paper makes the case for getting U.S. troops out of Syria. It does so first by explaining the circumstances that produced U.S. intervention there and by showing that the mission against ISIS succeeded. It then lays out the dangers of keeping troops in Syria indefinitely and counters the major arguments offered for staying in Syria.

U.S. intervention in the Syrian civil war

U.S. involvement in Syria’s civil war

The United States intervened in Syria’s civil war in two ways:

- Anti-Assad intervention: In 2012, the Obama administration began a limited attempt to overthrow the Assad regime by aiding rebels.

- Anti-ISIS intervention: In 2014, the United States launched an ultimately successful effort to liberate territory taken over by the Islamic State, using airstrikes and local proxies assisted by a small U.S. ground force.

This section explains the circumstances that led to those parallel efforts. Although regime change failed, ISIS’s caliphate was successfully destroyed.

Syria’s fracture

American policymakers tend to underestimate the difficulty of maintaining political order in weak states. They often conflate state repression with state strength and imagine that the natural alternative to autocratic rule is liberal democracy. Syria’s descent into a multi-sided civil war is another reminder of that error.

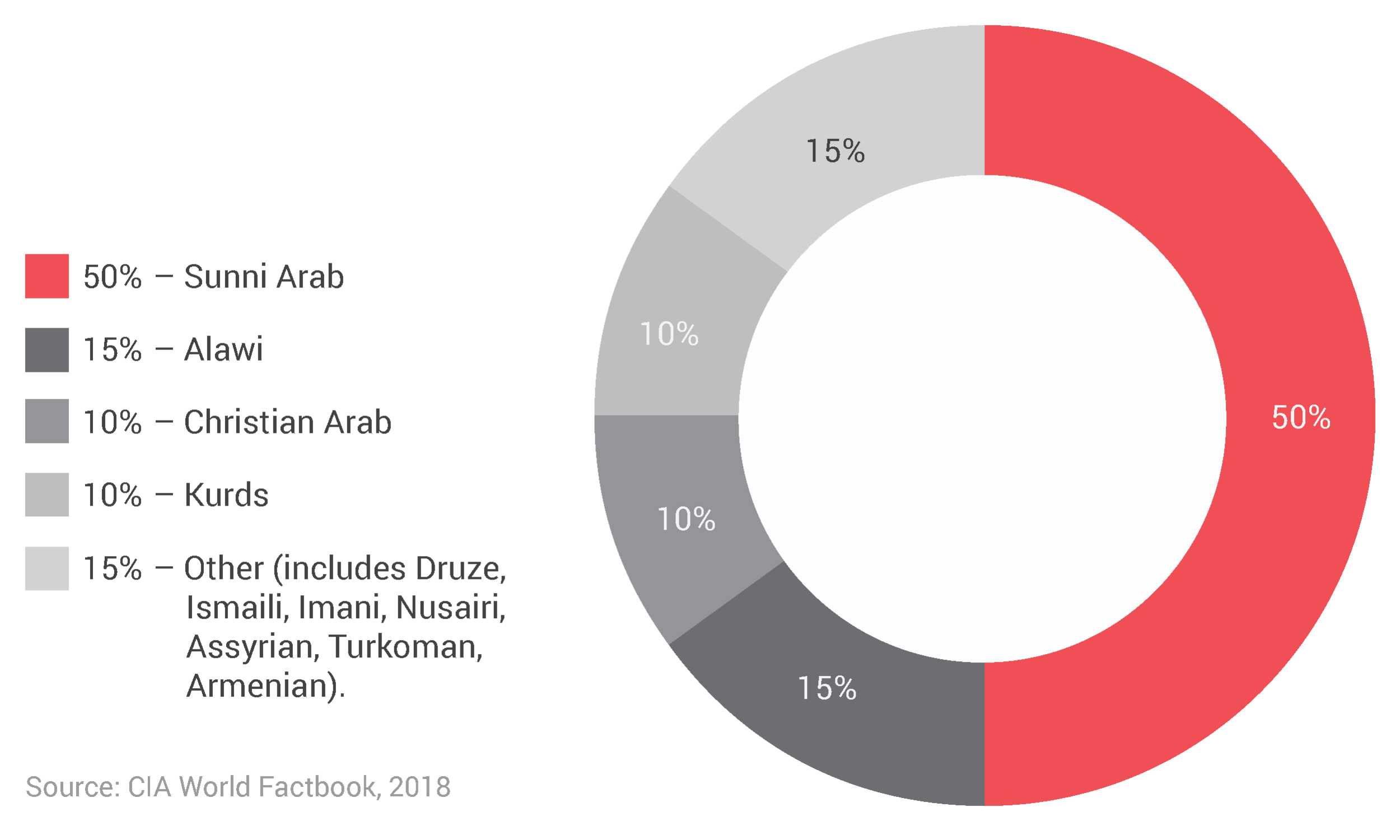

Syria is a poor, weak state: a “fragile mosaic” of communities prone to breaking apart.1 In the twentieth century, it emerged from Ottoman rule, became a French protectorate between the wars, and gained independence after World War II only to suffer a wave of military coups. The eighth coup, in 1970, installed Bashar al-Assad’s father, Hafez, a Baathist—an Arab nationalist and socialist—who ruled until his death in 2000, proving that Syria could be ruled enduringly, if not liberally. His regime, like his son’s, was dominated by co-religionists of the Alawite offshoot of Shiite Islam, and it relied on security services to dominate a Sunni-majority nation.

Breakdown of Syrian population

Other minority groups—such as Kurds, Christians, and Druze—tended to support the regime. Government forces put down Muslim Brotherhood-linked unrest in the Sunni community in 1964, in the 1970s, and in the early 1980s, culminating in the 1982 Hama massacre, where the Syrian army killed upwards of ten thousand civilians.2 From then until 2011, repression kept Syria fairly stable.

Protests broke out in the southern Syrian city of Daraa in March 2011 amid the “Arab Spring” rebellions and upheaval in Tunisia, Libya, and Egypt. These protests—mostly demonstrations—spread to various other mostly Sunni towns and centered on calls for political and economic reforms. The Assad regime responded with brutality, including military attacks on protestors and the widespread torture, rape, and execution of imprisoned activists by the security services.3

The crackdown on the protest movement quickly spawned a variety of armed groups seeking regime change, many with political headquarters in southern Turkey. Initially, the most prominent was the Free Syria Army (FSA), which consumed the alternative Free Officers Movement and attracted the bulk of the approximately 60,000 military personnel who reportedly defected from the Syrian Army in the first year of rebellion.4 The FSA’s leaders hoped it would serve as a military structure to coordinate the rebellion. It developed shaky ties to the Syrian National Council (later Syrian National Coalition), a Turkey- and Qatar-backed umbrella group dominated by exiles that sought to be the political voice of opposition to Assad.5

As the civil war intensified in 2012, the Assad regime increasingly relied on indiscriminate violence against rebels: mass executions, Scud missile launches, barrel bombs, and chemical weapons attacks.6

Deaths, refugees, and internally displaced persons (IDPs) from Syria’s civil war (2010–2019)

Islamist groups grew as a portion of the rebellion, partly because of foreign fighters and financial support from the Gulf States and Turkey.7 The most prominent was the Al-Qaeda-linked Al-Nusrah Front, which grew from consolidating local militias and foreign fighters.

The radicalization of the rebellion helped Assad paint all rebels as tainted by Islamist extremism, a move largely understood as a way to make it impossible for outside powers—including the United States—to fund, arm, and train radicals focused on regime change. According to some reports, the regime even intentionally swelled the ranks of Islamists rebels by releasing jailed extremists.8

The regime focused its forces in the populous central area of Syria between Damascus, the capital, and Aleppo, Syria’s largest city. Within that area, rebels controlled shifting pockets of territory including much of the countryside. In summer 2012, a coalition of rebel groups took much of Aleppo. Rebels also gained sway over an area in the southwest, near Jordan, and a larger swath of the northeast, near Turkey, largely in Idlib province.

The YPG took de facto control of northeast Syria and a smaller area around Afrin in the northwest. Islamists groups took areas to their south and east. A coalition of Islamists led by the Al-Nusrah front, which then contained fighters from ISIS, seized the eastern provincial capital of Raqqa in March 2013.

Even Damascus seemed vulnerable, with rebels holding much of the suburbs. In July 2012, a bomb in Syria’s National Security Headquarters killed the Defense Minister and his top deputy, Assad’s brother-in-law, plus two other top security officials, and wounded several others.9 The FSA and a jihadist group, the Salafist Liwa al-Islam, both claimed responsibility.

Effects of Syria’s civil war on GDP, population, and oil production (2010 vs. 2016)

From 2010 to 2016, Syria’s GDP decreased 75 percent, its population decreased 12.3 percent, and its production of oil decreased 97.4 percent. The discrepancy between the population figures here and the prior graphic is explained by births and differences in methods among sources.

President Obama backs the rebels

Many observers, including in the Obama White House, believed the Syrian government was losing its hold on power in 2012 and 2013.10 Rebel gains had disrupted Assad’s ability to reliably supply his already depleted forces, which in many cases were not deemed loyal enough to deploy.11 Damascus was reportedly running out of cash because of economic sanctions, dwindling oil sales, difficulties collecting revenues elsewhere, and the costs of prosecuting the war.12

Events in nearby countries encouraged the belief the rebels would win. The Arab Spring had felled longtime governments in Tunisia, Egypt, and Yemen. Rebels backed by foreign airpower had overthrown and killed Libya’s longtime dictator, Muammar Gaddafi. Intervention backers saw Libya as a blueprint for Syria.13

President Obama, joined by the heads of France, Germany, and the United Kingdom, called for Assad to step down in August 2011. Obama initially rejected a 2012 plan to arm and train FSA rebels while approving nonlethal aid.14 Informed by an intelligence report on the troubled history of past U.S. efforts to train and assist insurgents, Obama was skeptical the effort would work.15

Still, in 2013, after some indications of the Assad regime using chemical weapons, violating Obama’s famous “red line” warning that such attacks might bring a U.S. military response, he authorized CIA-training and lethal aid for rebel groups, though not on the scale some wanted.16 Obama also rejected calls from prominent interventionists—some within his administration, most in op-ed pages—to use U.S. airpower to create a haven for the rebels.17

Administration officials offered several rationales for intervening against Assad. One prominent view, expressed by Ben Rhodes, who eventually served as Deputy National Security Advisor, was that Assad’s actions made it important to be “doing something,” even if it seemed unlikely to work.18 Others believed aiding “moderate” rebels would offset extremism in the rebellion encouraged by Gulf states’ funding.19 Others saw the aid as a way to pressure Assad into a negotiated peace where he would leave office.20

After the August 2013 sarin gas attack in Ghouta, which killed upwards of 300 people, regime-change proponents advocated for a larger-scale U.S. push to unseat Assad. But Obama’s calculus did not shift much. The administration began to prepare for airstrikes against the Assad regime but seemed to decide instead on relatively limited punitive strikes. Even that proposal was controversial. When the Obama administration asked for authorization to attack Syrian government forces—a surprise after it ignored such constitutional niceties two years earlier regarding Libya—Congress seemed likely to follow the U.K. Parliament and reject the request for the authority to intervene.21

An offhand comment by Secretary of State John Kerry and Russian diplomacy forestalled the vote, ending the immediate possibility of U.S. bombing. Assad agreed to a deal, codified by a U.N. Security Council Resolution, to destroy Syria’s chemical weapons stockpiles with verification from international inspectors.22 The regime did declare and give up the bulk of its chemical weapons.23 But subsequent attacks showed that the regime retained some banned weapons.

The Assad regime survives

The Assad regime proved to be stronger than it seemed early in the civil war, a point apparently made by secret State Department reports in 2012.24 It retained strong support among Syria’s minority communities who were fearful about their fate under a different government or the absence of one.25 Even as the Syrian Army struggled to operate, local forces organized themselves to take on rebels in an array of militias drawn from groups with traditionally good ties to the regime.26

Outside support was also crucial to the regime’s survival. Russia supplied arms to the Syrian government before and throughout the civil war, and Russian forces began to bomb rebels on behalf of the regime started in 2015.27 Iran reportedly loaned Syria billions of dollars, in addition to funneling military experts and arms starting early on in the conflict.28 It provided elite forces to aid Syria’s military and organized Shiites from abroad, including a large number of Afghan refugees, into pro-government militias.29 Iran also encouraged the 2012 deployment of Lebanese Hezbollah to Syria, which ultimately supplied thousands of fighters.30 Iraqi Shiite militias tied to Iran also fought on behalf of the Assad regime, especially once ISIS was pushed out of its territory in Iraq.

Rebel disorganization was a third factor aiding the regime.31 The Syrian National Coalition—the rebels’ alleged political leadership in Qatar—struggled to influence events in Syria and fractured. The FSA’s efforts to unify command of their associated militias faltered, and made it difficult to aid them, at least if one cared where the weapons and fighters wound up.32 Islamists gained strength within the FSA structure and outside it, further tainting the rebels’ reputation.

Divisions and extremism among the rebels undermined CIA efforts to train and arm them. The program spent almost a billion dollars a year and achieved some initial tactical success against Syria government forces, but U.S. weapons and trainees wound up in the hands of other militias, including Al-Nusrah, and U.S.-trained forces could not prevent the Assad regime and its backers from retaking territory.33 CIA- and Pentagon-trained rebels even clashed with each other.34 In sum, from the start of the CIA training program, the rebels seemed too dysfunctional to win and too extreme to be an improvement over Assad even if they did.

The war on ISIS

Early in the civil war, Islamic State fighters from Iraq entered Syria. By the spring of 2013, ISIS’s leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi declared a caliphate in Iraq and Syria and attempted to subordinate Al-Nusrah, leading to their split and some armed clashes between the groups.35 ISIS quickly pushed its Islamist rivals aside to control much of eastern Syria, including Raqqa, which became its capital, and began encroaching on YPG-controlled territory. Thanks to its battlefield success, brutal reputation, and territory, ISIS began attracting recruits from around the world, many of them passing through Turkey.36

ISIS’s territorial gains and extremism fueled the coalition that destroyed it. In spring 2014, ISIS had taken Mosul from more numerous Iraqi forces, many of whom abandoned the battlefield without fighting.37 By the fall, as ISIS gained ground in Iraq’s Sunni triangle, speculation swirled that ISIS could conquer Baghdad.38 Also in 2014, ISIS began posting videos of its grisly executions online.39 Its notoriety also inspired a number of jihadi groups in the Middle East, Africa, and South Asia to take up its name, although evidence of operational links was usually lacking.40

Meanwhile, ISIS fighters and propagandists began issuing threats against the United States and European nations.41 Terrorist incidents linked to ISIS, or at least carried out by militants claiming to serve it, occurred in France, Belgium, Australia, Turkey, Egypt, Denmark, the United States, and a variety of other countries.42

These actions shifted U.S. public opinion in favor of military action in Syria and Iraq to counter ISIS.43 In August 2014, President Obama ordered the United States to begin airstrikes against ISIS in Iraq. The airstrikes were ostensibly to protect U.S. personnel in Erbil and the Yazidi minorities on Mount Sinjar. But the mission quickly grew into a continuous and geographically broader effort that lent foreign airpower to the fight against ISIS in support of indigenous ground forces in Syria.

The United States did the bulk of the bombing, but Australia, Bahrain, Belgium, Denmark, France, Jordan, the Netherlands, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and especially the U.K. also conducted airstrikes. Canada, Italy, Germany, Poland, and even Singapore provided aircraft for intelligence or surveillance, and a variety of other nations provided military trainers. Sixty-six nations contributed to the coalition in some fashion, according to the U.S. State Department.44

The effort against ISIS, like that against Assad, included a “train and assist” element, with the Pentagon vetting and training forces. Initial results were embarrassing. The training pipeline produced only a smattering of fighters, and those who were deployed to Syria were quickly routed.45

The effort to supply and train Kurdish YPG forces went better. The Kurds were already capable fighters and began making steady progress against ISIS with U.S. air support.46 In an effort to allow a force less offensive to local Arabs and the Turks to retake non-Kurdish territory held by ISIS, the United States helped broker an alliance between the Kurds, local Arab forces, and others, which was christened the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF).47 In practical terms, the SDF was dominated by the YPG, and Turkey’s leaders still viewed them as an enemy force.48

In the fall of 2015, the Obama administration, which had previously denied that there would be U.S. “boots on the ground” in Syria, acknowledged the deployment of hundreds U.S. special operations forces there, in theory to support the SDF and help target airstrikes.49 By late 2017, the Pentagon admitted that it had 2,000 troops in Syria, not the 500 it had previously announced.50 Congress provided little oversight.

As the Trump administration came in to office in 2017, ISIS was losing territory in both Syria and Iraq, its ranks decimated and its recruitment efforts slowed to a trickle.51 The SDF fully took Raqqa in October, after 11 months of fighting. By March 2019, they had taken all ISIS’s territory.52

The end of U.S. military intervention?

The Trump administration has pursued a confused policy in Syria, at least rhetorically. After six months in office, the administration ended the effort to overthrow Assad, but top officials kept talking about overthrowing him, and some reportedly still do.53 Once ISIS was nearly beaten, the administration announced a broad set of new goals for U.S. forces in Syria. President Trump then announced the swift departure of U.S. troops, before reversing course and keeping a small force indefinitely.

The administration initially seemed to follow the Obama administration’s eventual acceptance of Assad’s rule. However, in both April 2017 and April 2018, Trump ordered, without congressional authorization, punitive cruise missile strikes against Syria following chemical attacks on rebel-held areas. Trump expressed disdain for Assad on both occasions, and in 2018, he mocked Russia’s insistence that it would shoot down any incoming missiles.54

In January 2018, Secretary of State Rex Tillerson called for Assad’s ouster and suggested that U.S. forces would remain in Syria indefinitely to push for a post-Assad settlement to counter Iranian influence.55 But by March, Tillerson had been fired, and Trump said that with ISIS’s defeat, the United States would pull forces out of Syria “soon.”56

U.S. policy appeared to shift again in the fall when National Security Advisor John Bolton and the U.S. envoy to Syria, Jim Jeffrey, each said that U.S. forces would remain in Syria to compel Iran’s departure, to achieve ISIS’s “enduring defeat”—a goal they left undefined—and to influence peace talks.57 Jeffrey denied that the aim was Assad’s ouster but said the United States would not provide aid toward Syria’s reconstruction unless the regime became “fundamentally different”—criteria he did not define.58

On December 19, 2018, President Trump appeared to discard that policy, announcing via Twitter the defeat of ISIS and imminent withdrawal of U.S. forces from Syria. The decision, which seemed to surprise most of Trump’s advisors, led to the resignations of Secretary of Defense Jim Mattis and U.S. envoy to the anti-ISIS coalition, Brett McGurk.59 Trump’s decision apparently came partly because of lobbying in phone calls from Turkish President Recep Erdogan, where Trump reportedly told him, “It’s all yours. We’re done.”60

A cavalcade of criticism met Trump’s pullout announcement. A bipartisan Senate press conference, media reports, and parades of op-ed columnists attacked the decision.61 The White House soon amended the withdrawal timetable to four-months and walked back the President’s offer to Turkey.62

U.S.-led coalition anti-ISIS strikes in Syria

In early February 2019, Trump stated that U.S. forces could return to Syria to attack ISIS, if necessary.63 Later that month, the White House announced 400 U.S. servicemembers would remain in Syria to help combat ISIS; maintain the al-Tanf garrison near the Jordanian and Iraqi border, which is likely seen as a way to disrupt Iranian shipments and to engage in some sort of policing mission to protect the Kurds.64 It is likely that the overt presence of these forces will be accompanied by a larger, covert group of intelligence operatives and special operations forces.65

Success against ISIS, failure against Assad

Why did one U.S. intervention in Syria succeed and the other fail? Level of effort is one obvious difference. The United States launched airstrikes against ISIS and deployed ground forces to aid the SDF. By contrast, its attack on regime targets after chemical weapons attacks were militarily insignificant. But U.S. exertion seems a secondary explanation at best.

The lesser effort against Assad reflected recognition of its limited prospects. Assad has huge advantages that ISIS lacked: the backing of powerful patrons, a capable military, and as it turns out, a deeper base of political support. U.S. aid to Assad’s rebel opponents may simply have increased Russian and Iranian effort to protect his rule.66 Rebels’ initial success and rising extremism caused the organization of rival militias where the regime was weak.

One could argue these realities are only visible with the benefit of hindsight, but in fact they were evident at the time, even to some of those who implemented U.S.-Syria policy. Phil Gordon, who served as White House Coordinator for the Middle East, North Africa, and the Persian Gulf Region from 2013 to 2015, describes what he realized by the end of his service in the administration:

“It wasn’t realistic to get rid of Assad. I didn’t see a path of doing so without a major U.S. intervention that would escalate the conflict. And even if it succeeded, [it] could be a version of catastrophic success, where you create a vacuum that extremists would fill.”67

Others, possibly including President Obama, saw things this way early in the civil war, warning that pushing for Assad’s overthrow was likely to fail and prolong the civil war—or produce potentially worse results if successful.68

ISIS, by contrast, was so extreme and bloodthirsty that it motivated a large chunk of the world’s nations to attack it. Its local enemies proved relatively capable, especially the SDF. In the future, its ability to survive as a guerrilla or terrorist organization depends on whether it retains some support among Sunnis in Iraq and Syria. Whether oppression will keep some group of Syrians or Iraqis desperate enough to risk supporting ISIS’s self-defeating extremism is an open question.69

The need for withdrawal

Some criticism of the Trump administration’s process surrounding the decision to withdraw was fair. But one need not defend the nature of the announcement to recognize that the policy serves U.S. security interests. The idea of fostering regime change was never good and has failed in any case. The U.S. military achieved its mission of destroying ISIS’s caliphate. Leaving U.S. forces in Syria now involves large risks without any security upside.

Escalation risks

Maintaining a U.S. military presence in Syria risks wider war against another state with forces there. The multifaceted nature of the Syrian civil war and the fog of war create various opportunities for unintentional clashes or small skirmishes that could trigger larger conflicts. For example, a variety of forces—the U.S.-backed SDF, Russians, pro-Syrian government militias, and Iranian-backed forces—are active in or around Deir ez Zor, the energy-producing and sparsely-populated region in Syria’s southeastern desert. Deconfliction lines have been established, but several clashes have occurred anyway. In February 2018, the approach of pro-regime Syrian forces toward U.S. forces led to a U.S. barrage that killed scores.70 Similar issues may occur if Kurdish forces, encouraged by U.S. backing, resist regime efforts to reclaim oil fields needed to fund reconstruction efforts.71

Russia

Russia has decades-long ties to the Assad governments and has maintained a naval base in Tartus since 1971. Those ties mean Russian forces will remain while the war continue and probably longer. The proximity of U.S. and Russian forces on the ground in Syria and in the air over it generates risk that the two powers could end up in direct conflict.

U.S. and Russian forces already have exchanged threats and even fire a number of times in Syria. In February 2018, U.S. special operators and airstrikes reportedly engaged a large group—possibly 100 or more—Russian “mercenaries” in a prolonged four-hour battle.72 Months later, U.S. Special Envoy Jeffrey remarked that “this has occurred about a dozen times in one place or another in Syria,” and “there have been various engagements [with the Russians in Syria], some involving exchange of fire, some not.”73 This alarming suggestion that U.S. forces were occasionally shooting at a nuclear armed rival elicited strangely little press or congressional attention.

Iran

Iran, like Russia, has long-standing ties to the Assad regime, which invited it to deploy forces there. The odds of Iranian advisors and the militias Iran backs departing Syria prior to the civil war’s end are small. Making their withdrawal a condition for U.S. withdrawal will fail while letting Iran dictate the U.S. military’s schedule. Even those eager to confront Iran might agree that Syria is a poor place to do so, given its advantages there.

Iranian shipments to Hezbollah or other forces are unfortunate but not new. Trying to use Syria’s civil war as an opportunity to address this issue could provoke more clashes. For those in the Trump administration who want to confront Iran, that may be welcome. But a U.S.-Iran conflict could ignite much of the region; lead to a prolonged war that erodes U.S. power, like Iraq; and tie down U.S. forces dealing with Iran for decades.

Israel has continually bombed Iranian-linked forces across Syria this year while demanding their exit and pledged to attack them throughout Syria.74 Iranian forces have apparently responded by shelling the Israeli-held Golan Heights.75 Israel does not need U.S. help defending its northern border, but U.S. forces could be drawn into an Israel-Iran clash, especially if Iranian-backed militias target U.S. forces in response to an Israeli strike.

Turkey

Turkey is the one state in Syria that might draw the United States into a fight on its side or against it. As a fellow NATO member, Turkey could demand U.S. protection if it is attacked. In late 2015, Turkey shot down a Russian jet that briefly crossed its airspace on a bombing run. Tensions between Turkey and Russia were high for a time, although before dramatically improving thanks to the Astana peace process and other measures. Tensions could peak again due to the circumstance in Idlib province, where the jihadist group Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) has consolidated power under Turkey’s ostensible watch. A Syrian or Russian offensive against HTS would threaten Turkish forces stationed at observation posts there.76

At the same time, relations between the United States and Turkey have suffered because of U.S. support for the Kurds. Turkey views the SDF as an extension of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, which it regards as a terrorist and insurgent organization threatening its borders. Turkey has attacked Kurdish forces across the border several times and threatens to do so again.77 To defuse tensions, U.S. and Turkish forces struck a deal to both patrol near the northeast city Manbij as Kurdish forces withdraw from the area gradually.78 In October, U.S. forces briefly came under fire from a Turkish-backed militia.79 Given the limited control both Ankara and Washington have over their local allies, combined with general confusion in war, a U.S.-Turkish clash remains a possibility.

No benefit justifies these dangers. Washington should only risk potentially catastrophic escalation with rival powers, especially nuclear armed-Russia, when America’s security is directly threatened. The stakes in Syria are far too low to risk such an outcome, especially with ISIS’s demise.

ISIS’s defeat and mission creep

Much criticism of the decision to exit Syria centers on the president’s declaration that ISIS is defeated. The conventional wisdom in Washington holds that U.S. security requires ISIS’s “enduring defeat” and staying in Syria to pursue an extended counterinsurgency mission. That is militarily unattainable and thus a recipe for a permanent military presence in Syria.

ISIS’s territorial defeat is meaningful, contrary to much commentary. ISIS fought tenaciously to preserve its caliphate and lost it all. It lost an uncertain but large portion of its fighters. To say that is not defeat begs the question of what is.

It is true that most terrorist organizations are clandestine and can be more easily targeted when they hold ground. But territory has real benefits for the organization of political violence.

ISIS-held territory in Syria and Iraq

The U.S.-led coalition destroyed the last remnant of ISIS’s caliphate in March 2019.

Territory facilitates the extraction of rents from economic activity to fund the insurgency or terrorist acts. Even under the threat of airstrikes, territory eases communication among militants, which aids training, the division of labor, arms distribution, and other steps vital to organizing violence. Clandestine groups, harried by security forces or police, rarely achieve violence on the scale of even insurgent groups that have these advantages.80

Territorial gains also feed propaganda and recruitment. ISIS’s success at winning battles and taking territory in Syria and Iraq, more than its heralded social media efforts, won it global fame to the point that misguided young people around the world took up its name in committing terrorist acts or travelled to fight for it.81 In losing its caliphate, ISIS lost much of its allure as an idea or brand.

Avoiding mission creep

Keeping forces in Syria to combat post-caliphate ISIS is unnecessary, risky, and liable to expand into a protracted stay. The 2,000 U.S. forces currently in the northeast portion of Syria are not sufficient to hunt a clandestine organization spread out across much of Syria, most of which will be essentially off-limits to U.S. forces. Even if that were not so, the policing effort would require forces far in excess of what the United States has deployed and an occupation with no obvious end.82

Infeasible objectives produce indefinite missions and failure. That is something the Department of Defense seems to miss in a September 2018 report, which admitted that ISIS had “lost roughly 99 percent of the territory in Syria,” while still warning that it remained an “adaptive organization capable of exploiting vulnerabilities in the security environment” that is “well-positioned to rebuild and work on enabling its physical caliphate to re-emerge.”83 Given these attributes, one struggles to envision what the DoD would characterize as the group’s “defeat.”

Eastern Syria and western Iraq are not likely to be fully pacified in the near future. In pursuit of ISIS’s “enduring defeat,” U.S. forces might slide into long-term policing missions that draw attacks, as in Manbij, where four Americans were recently killed by a suicide bomber.84 As the Syrian government regains control of its country, it may take actions to eject U.S. forces, along with its militia backers. U.S. forces, already at risk of attack from Sunni insurgents in Iraq and Syria, may gain the violent attention of their Shiite adversaries.

Keeping U.S. forces in Syria may simply exacerbate these risks. Using a small contingent of forces to hunt ISIS, poke at Iran, and protect Kurds may only spread them thinly enough to fail quickly and create demand for more. The remaining force will be enough to get into trouble but not enough to win any serious fight without support.

A small force may represent something of down payment towards the larger costs that more ambitious, recent efforts in the region have entailed. Another effort to manage sectarian conflict to shape local politics in a pro-American direction is unlikely to have a better outcome than the recent efforts in Iraq or Afghanistan. It will pit U.S. forces against the government of the state and potentially both Shiite and Sunni extremists. It will be another dubious small war that ties down U.S. forces and keeps them from preparation for clearer and more important missions.85

Keeping U.S. troops in Syria is bad counterterrorism policy

The best way to combat ISIS, in the long-term, is to remove U.S. forces from Syria and let local actors take the lead in combatting its remnants. U.S. forces attract resistance that might aid ISIS’s survival.86 And U.S. ground forces can perform few useful counterterrorism missions in Syria. ISIS’s primary hunters are not U.S. forces but the Kurds, who have self-interested reasons to keep up the hunt. None of the other major actors operating in Syria—the Iranian-backed forces, the Russians, the Assad regime, its loyalist militias, and even most other Sunni groups—will tolerate ISIS forces.

In the unlikely event that those efforts to combat ISIS fail, leaving now would not prevent the United States from returning, as the president said, hopefully with congressional authorization. The U.S. surveillance and strike capability does not disappear with its ground presence. As in Yemen, Pakistan, Libya, and elsewhere around the globe, U.S. forces retain the ability to strike terrorists without military occupation.

Other bad reasons for staying

Advocates of keeping U.S. ground forces in Syria make three primary arguments for keeping U.S. forces in Syria, besides the idea that they should stay to fight ISIS:

- Leaving will open a vacuum and cede Syria to U.S. rivals

- Leaving abandons the Kurds

- Leaving will deny the United States the ability to help shape Syria’s post-war order

Vacuums and crescents

The claim that the United States should not leave Syria to Russia or Iran makes little sense.87 To begin with, both countries have a long history of influence in Syria. Both were invited by the Assad regime to help win the war and would be nearly impossible to extract prior to that outcome—it would require a massive U.S. military commitment. Both are proximate states to Syria (the United States is 6,000 miles away); both perceive strong interests in maintaining the government’s rule; and both have a strong base of support there, especially Iran. Those facts make Syria a poor arena in which to compete with those powers, even if one is after avoidable competition.

Syria is not a prize that will propel outside states to greater regional power.88 Syria’s leadership is unlikely to cede its limited oil and gas revenue to partners.89 It has little else to offer outside forces, beyond the chance to participate in managing a sectarian civil war. There is no strategic basis for denying adversaries such burdens.

The oft-repeated idea that the United States should stay on in Syria to prevent a “Shiite crescent” linking Tehran to Lebanon, and thus allowing Iran to easily supply Hezbollah, suffers major flaws.90 This land route—possible because of the failed U.S. war in Iraq—is not a threat to Americans. Iran has for decades flown and shipped arms and aid to its proxies. While Hezbollah remains problematic, it has not attacked an American target since the mid-1990s, and Israel is well-equipped to see to its own security and deter attacks from Syria without a U.S. military presence in Syria.91 The return of a coherent Syrian government that limits jihadist threats there and provides a return address for deterrence is comparatively good for Israel.92 Israel has co-existed with Syria and an Assad ruler for decades.

The Kurds aren’t U.S. wards

The Kurdish SDF or YPG combatted ISIS out of self-preservation, not as a favor to Americans—but simply leaving them to face Turkish attacks would be capricious. As discussed, they should be encouraged to negotiate something like their pre-war situation with the Assad regime to avoid attacks from Turkey. They have reportedly kept an open line to Damascus for this reason.93

Handing western Syria to Turkey is a bad idea. Turkey’s focus on Kurds and history of tolerating jihadists in Syria means its willingness to go after ISIS’s remnants is questionable. Allowing Turkish forces to take over U.S. positions would also put Kurdish forces in needless peril. U.S. leaders should instead cheer Kurdish efforts to restore something like the status quo ante bellum, where Syrian government forces controlled the border, and the YPG functioned without being attacked by Turkey.94 That is what the Kurds were pursuing early in 2019, even as some Trump administration officials discouraged them.95 The United States can push Assad, if need be through Russia, to refrain from targeting Kurds and other rebels that negotiate ceasefires, and to allow those who America helped to battle ISIS to emigrate.96

But sooner rather than later, the Kurds have to once again make their own way in Syria. The United States never promised to become the permanent guarantors of an autonomous Kurdish statelet.97 Doing so would pit U.S. forces in a permanent standoff with NATO ally Turkey and the Syrian government. Aligning with a party to secure a common interest does not require adoption of all its interests in perpetuity.

The limited leverage troops provide isn’t enough

The argument for leaving U.S. troops in Syria with the most merit is to improve Washington’s hand in negotiations over the war’s termination. But Washington has not been particularly involved in recent negotiations about the war because U.S. demands—a full withdrawal of Iran-linked forces and the removal of Assad from power—were poison pills.98

Even with more realistic positions, the United States has limited leverage. What power it has comes more from its potential to use force than the limited force now deployed. Even as U.S. forces leave, that leverage should be used to push for an end to mass execution and other blatant human rights abuses, to allow the emigration of U.S.-backed rebels who seek it, to push for the peaceful reintegration of those that do not, and to allow international organizations to provide aid in war-torn areas.

Disentangling to protect U.S. interests

The Assad regime’s brutality and the seeming decency of many of its early opponents gave U.S. support for rebels a specious allure. But regime change was never a responsible policy. U.S. support for rebels did not give them much chance to win—it merely intensified and prolonged the civil war. Since the start of civil war, Syria’s likely futures were all grim: rule by Assad or another authoritarian like him, or continued war and the humanitarian disaster and extremism that accompanied it. Even a U.S. invasion to overthrow Assad would not have changed that.

The grim promise in Syria is that regime victory will at last end the war. That will not bring justice, but it will allow a rough peace that should let many refugees return home, see more of Syria’s wealth flow to improving Syrians’ welfare, and increase their life expectancy. It will also aid the U.S. goal in Syria of eliminating ISIS and other transnational terrorist organizations deemed threatening. The United States should not celebrate Assad’s victory, but it should accept the reality that he will remain in power. U.S. leaders should use their limited leverage over the Syrian government to try to reduce its worst excesses.

Staying in Syria threatens to drive adversaries into allying against the United States; to inflame Islamist-nationalist sentiments in Iraq and Syria, making U.S. forces targets; and to risk U.S. conflict with Russia, Iran, Turkey, and Syria for no good reason. Staying also ties down U.S. forces and limits their focus on core missions.

Pursuing ISIS’s “enduring defeat” with ground forces would expand the U.S. mission into a vague and dangerous nation-building project. Remaining is also poor counterterrorism strategy, given the limited number and range of U.S. forces there, the other forces—including the Syrian government—willing do that work, and the likelihood that staying will do more to help ISIS’s potential resuscitation than to prevent it.

No coherent security rationale justifies running those risks. The United States is leaving no prize in Syria to outside, adversarial powers. The Kurds can deal with Assad and escape Turkey’s wrath.

In Syria’s civil war, the United States has the opportunity to reduce its burdens, avoid further entanglement, and ease great power tensions, while having achieved its key goal. Washington should accept the limited victory, rather than staying and finding new trouble.

Endnotes

1 Martha Kessler, Syria: Fragile Mosaic of Power, (Washington, DC: National Defense University Press, 1987.)

2 Estimates vary widely. Raphaël Lefèvre, Ashes of Hama: The Muslim Brotherhood in Syria (Oxford: Oxford University Press 2013), 128.

3 Janine di Giovanni, The Morning They Came for Us: Dispatches from Syria (New York: Liveright, 2016). Ben Taub, “The Assad Files: Capturing the Top-secret Documents that Tie the Syrian Regime to Mass Torture and Killings,” The New Yorker, April 18, 2016, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2016/04/18/bashar-al-assads-war-crimes-exposed; Recently unlawful executions of prisoners have accelerated (AQ: Is this preceding clause part of the name of the article? Unsure why it’s here). Louisa Loveluck and Zakaria Zakaria, “Syria’s Once-teeming Prison Cells Being Emptied by Mass Murder,” Washington Post, December 23, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2018/world/syria-bodies/.

4 Charles Lister, The Free Syrian Army: A Decentralized Insurgent Brand, the Brookings Project on U.S. Relations with the Islamic World Analysis Paper No. 26, November 2016, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/iwr_20161123_free_syrian_army1.pdf.

5 Ken Sofer and Juliana Shafroth, “The Structure and Organization of the Syrian Opposition,” Center for American Progress, May 14, 2013, https://www.americanprogress.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/StructureAndOrganizationSyrianOpposition-copy.pdf.

6 “Houla Massacre: UN Blames Syria Troops and Militia,” BBC, August 15, 2012, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-19273284; Michael R. Gordon and Eric Schmitt, “Syria Fires More Scud Missiles at Rebels, U.S. Says,” New York Times, December 20, 2012, https://www.nytimes.com/2012/12/21/world/middleeast/syrian-forces-lobbing-more-scud-missiles-at-rebels-us-says.html; Alicia Sanders-Zakre, “Timeline of Syrian Chemical Weapons Activity, 2012-2018,” Arms Control Association, November 28, 2018, https://www.armscontrol.org/factsheets/Timeline-of-Syrian-Chemical-Weapons-Activity; “‘Death Everywhere’: War Crimes and Human Rights Abuses in Aleppo, Syria,” Amnesty International, April 24, 2015, https://www.amnesty.org.uk/files/webfm/Documents/issues/mde2413702015english.pdf.

7 Kim Sengupta, “Turkey and Saudi Arabia Alarm the West by Backing Islamist Extremists the Americans Had Bombed in Syria,” Independent (U.K.), May 12, 2015, https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/middle-east/syria-crisis-turkey-and-saudi-arabia-shock-western-countries-by-supporting-anti-assad-jihadists-10242747.html.

8 Phil Sands, Justin Vela, and Suha Maayeh, “Assad Regime Abetted Extremists to Subvert Peaceful Uprising, Says Former Intelligence Official,” The National, January 21, 2014, https://www.thenational.ae/world/assad-regime-abetted-extremists-to-subvert-peaceful-uprising-says-former-intelligence-official-1.319620.

9 CNN Wire Staff, “Jordan’s King Calls Syria Attack ‘A Tremendous Blow’ to al-Assad Regime,” CNN, July 18, 2012, https://www.cnn.com/2012/07/18/world/meast/syria-reaction-king-abdullah/.

10 Helene Cooper, “Washington Begins to Plan for Collapse of Syrian Government,” New York Times, July 18, 2012, https://www.nytimes.com/2012/07/19/world/middleeast/washington-begins-to-plan-for-collapse-of-syrian-government.html.

11 Luke Harding, “Syrian Army Supply Crisis Has Regime on Brink of Collapse, Say Defectors,” The Guardian, July 27, 2012, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2012/jul/27/syrian-army-brink-of-collapse; Brian Michael Jenkins, “The Dynamics of Syria’s Civil War,” RAND Corporation, 2014, https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/perspectives/PE100/PE115/RAND_PE115.pdf.

12 Joby Warrick and Alice Fordham, “Syria Running Out of Cash as Sanctions Take Toll, But Assad Avoids Economic Pain,” Washington Post, April 24, 2012, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/syria-running-out-of-cash-as-sanctions-take-toll-but-assad-avoids-economic-pain/2012/04/24/gIQAO2njfT_story.html.

13 Shadi Hamid, “Why We Have a Responsibility to Protect Syria,” The Atlantic, January 26, 2012, https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2012/01/why-we-have-a-responsibility-to-protect-syria/251908/; Anne-Marie Slaughter, “Syrian Intervention is Justifiable, and Just,” Washington Post, June 8, 2012, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/syrian-intervention-is-justifiable-and-just/2012/06/08/gJQARHGjOV_story.html.

14 Elise Labott, “Obama Authorized Covert Support for Syrian Rebels, Sources Say,” CNN, August 1, 2012, https://www.cnn.com/2012/08/01/us/syria-rebels-us-aid/index.html.

15 Mark Mazzetti, “C.I.A. Study of Covert Aid Fueled Skepticism About Helping Syrian Rebels,” New York Times, October 14, 2014, https://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/15/us/politics/cia-study-says-arming-rebels-seldom-works.html; Ewen MacAskill, “Obama: Post-Assad Syria of Islamist Extremism is Nightmare Scenario,” The Guardian, March 22, 2013, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/mar/22/obama-syria-assad-syria-extremists.

16 Mark Mazzetti, Michael R. Gordon, and Mark Landler, “U.S. Is Said to Plan to Send Weapons to Syrian Rebels,” New York Times, June 13, 2013, https://www.nytimes.com/2013/06/14/world/middleeast/syria-chemical-weapons.html; Greg Miller, “CIA Ramping Up Covert Training Program for Moderate Syrian Rebels,” Washington Post, October 2, 2013, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/cia-ramping-up-covert-training-program-for-moderate-syrian-rebels/2013/10/02/a0bba084-2af6-11e3-8ade-a1f23cda135e_story.html.

17 John McCain, Joseph I. Lieberman, and Lindsey O. Graham, “McCain, Lieberman and Graham: The Risks of Inaction in Syria,” Washington Post, August 5, 2012, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/mccain-lieberman-and-graham-the-risks-of-inaction-in-syria/2012/08/05/4a63585c-dd91-11e1-8e43-4a3c4375504a_story.html; Michael R. Gordon and Eric Schmitt, “David Petraeus Urges Stronger U.S. Military Effort in Syria,” New York Times, September 22, 2015, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/09/23/world/middleeast/david-petraeus-urges-stronger-us-military-effort-in-syria.html; Ruth Sherlock, “Hillary Clinton Will Reset Syria Policy Against ‘Murderous’ Assad Regime,” The Telegraph (U.K.), July 29, 2016, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2016/07/29/hillary-clinton-will-reset-syria-policy-against-murderous-assad/; Mark Mazzetti and Peter Baker, “U.S. Is Debating Ways to Shield Syrian Civilians,” New York Times, October 22, 2015, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/10/23/world/middleeast/us-considering-ways-to-shield-syrian-civilians.html.

18 Ben Rhodes, “Inside the White House during the Syrian ‘Red Line’ Crisis” The Atlantic, June 3, 2018, https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2018/06/inside-the-white-house-during-the-syrian-red-line-crisis/561887/.

19 Charles Glass, “‘Tell Me How This Ends’: America’s Muddled Involvement with Syria,” Harper’s Magazine (February 2019).

20 Faysal Itani, “The End of American Support for Syrian Rebels Was Inevitable,” The Atlantic, July 21, 2017, https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2017/07/trump-syria-assad-rebels-putin-cia/534540/; Mark Landler, “51 U.S. Diplomats Urge Strikes against Assad in Syria,” New York Times, June 16, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/06/17/world/middleeast/syria-assad-obama-airstrikes-diplomats-memo.html.

21 Burgess Everett, “Tough Hill Vote on Syria Fades,” Politico, September 14, 2013, https://www.politico.com/story/2013/09/congress-syria-vote-096806.

22 “The US-Russia Agreement on Syria’s Chemical Weapons Deal in Full,” The Telegraph (U.K.), September 14, 2013, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/middleeast/syria/10309286/The-US-Russia-agreement-on-Syrias-chemical-weapons-deal-in-full.html.

23 Alicia Sanders-Zakre, “What You Need to Know About Chemical Weapons Use in Syria,” Arms Control Association, September 26, 2018, https://www.armscontrol.org/blog/2018-09-26/what-you-need-know-about-chemical-weapons-use-syria.

24 Josh Rogin, “Obama Stifled Hillary’s Syria Plans and Ignored Her Iraq Warnings for Years,” The Daily Beast, August 14, 2014, https://www.thedailybeast.com/obama-stifled-hillarys-syria-plans-and-ignored-her-iraq-warnings-for-years.

25 Jenkins, “Dynamics,” 6–7.

26 Aron Lund, “Who Are the Pro-Assad Militias?” Carnegie Middle East Center, March 2, 2015, https://carnegie-mec.org/diwan/59215.

27 Richard Galpin, “Russian Arms Shipments Bolster Syria’s Embattled Assad,” BBC, January 30, 2012, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-16797818.

28 Karim Sadjadpour, “Iran’s Unwavering Support to Assad’s Syria,” Combating Terrorism Center Sentinel, 6, no. 8, https://ctc.usma.edu/irans-unwavering-support-to-assads-syria/.

29 Phillip Smyth, “Iran’s Afghan Shiite Fighters in Syria,” The Washington Institute, Policy Watch 2262, June 3, 2014, https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/view/irans-afghan-shiite-fighters-in-syria; Jubin Goodarzi, “Iran and Syria at the Crossroads: The Fall of the Tehran-Damascus Axis?” The Wilson Center, Viewpoints 35 (August 2013), https://www.wilsoncenter.org/sites/default/files/iran_syria_crossroads_fall_tehran_damascus_axis.pdf.

30 Marisa Sullivan, “Hezbollah in Syria,” Institute for the Study of War, Middle East Security Report 19 (April 2014), http://www.understandingwar.org/report/hezbollah-syria; David Hirst, “Hezbollah Uses Its Military Power in a Contradictory Manner,” The Daily Star (Lebanon), October 23, 2012, http://www.dailystar.com.lb/Opinion/Commentary/2012/Oct-23/192380-hezbollah-uses-its-military-power-in-a-contradictory-manner.ashx#axzz2AJrVn2Ik.

31 Carla E. Humud, Christopher M. Blanchard, and Mary Beth D. Nitkin, “Armed Conflict in Syria: Overview and U.S. Response,” Congressional Research Service (CRS Report), October 13, 2017, 6–7.

32 Lister

33 Mark Mazzetti, Adam Goldman and Michael Schmidt, “Behind the Sudden Decision Death of a $1 Billion Secret C.I.A War in Syria,” New York Times, August 2, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/02/world/middleeast/cia-syria-rebel-arm-train-trump.html.

34 W. J. Hennigan, Brian Bennett, and Nabih Bulos, “In Syria, Militias Armed by the Pentagon Fight Those Armed by the CIA,” The Los Angeles Times, March 27, 2016, https://www.latimes.com/world/middleeast/la-fg-cia-pentagon-isis-20160327-story.html.

35 Basma Atassi, “Qaeda Chief Annuls Syrian-Iraqi Jihad Merger,” Al Jazeera, June 9, 2013, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/middleeast/2013/06/2013699425657882.html; Lizzie Dearden, “Al-Qaeda Leader Denounces ISIS ‘Madness and Lies’ as Two Terrorist Groups Compete for Dominance,” Independent (U.K.), January 13, 2017, https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/middle-east/al-qaeda-leader-ayman-al-zawahiri-isis-madness-lies-extremism-islamic-state-terrorist-groups-compete-a7526271.html.

36 Les Picker, “Where Are ISIS Foreign Fighters Coming From?” The National Bureau of Economic Research, June 2016, https://www.nber.org/digest/jun16/w22190.html; Zachary Laub, “Who’s Who in Syria’s Civil War,” Council on Foreign Relations, April 28, 2017, https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/whos-who-syrias-civil-war.

37 Chelsea J. Carter, Salma Abdelaziz, and Mohammed Tawfeeq, “Iraqi Soldiers, Police Drop Weapons, Flee Posts in Portions of Mosul,” CNN, June 13, 2014, https://www.cnn.com/2014/06/10/world/meast/iraq-violence/index.html.

38 Jim Sciutto and Greg Botelho, “Iraqis ‘Up Against the Wall’ as ISIS Threatens Province Near Baghdad,” CNN, October 10, 2014, https://www.cnn.com/2014/10/10/world/meast/isis-threat/index.html.

39 “UN Commission of Inquiry: Syrian Victims Reveal ISIS’s Calculated Use of Brutality and Indoctrination,” UN Human Rights Council, November 14, 2014, https://www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/HRC/Pages/NewsDetail.aspx.

40 Daniel Byman, “ISIS Goes Global,” Foreign Affairs (March/ April 2016), https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/middle-east/isis-goes-global.

41 Michael Georgy and Mariam Karouny, “ISIS Is Now Directly Threatening to Attack American and European Targets,” Business Insider, August 20, 2014, https://www.businessinsider.com/isis-now-openly-threatening-attacking-us-targets-2014-8.

42 Christopher M. Blanchard and Carla E. Humud, “The Islamic State and U.S. Policy,” Congressional Research Service, September 25, 2018, https://www.everycrsreport.com/reports/R43612.html.

43 Dan Balz and Peyton M. Craighill, “Poll: Public Supports Strikes in Iraq, Syria; Obama’s Ratings Hover Near His All-Time Lows,” Washington Post, September 9, 2014, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/poll-public-supports-strikes-in-iraq-syria-obamas-ratings-hover-near-his-all-time-lows/2014/09/08/69c164d8-3789-11e4-8601-97ba88884ffd_story.html.

44 “The Global Coalition to Defeat ISIS,” U.S. Department of State, accessed February 10, 2019, https://www.state.gov/s/seci/.

45 Tom Vanden Brook, “Pentagon’s Failed Syria Program Cost $2 Million per Trainee,” USA Today, November 5, 2015, https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/world/2015/11/05/pentagon-isil-syria-train-and-equip/75227774/; Paul McLeary, “The Pentagon Wasted $500 Million Training Syrian Rebels. It’s About to Try Again,” Foreign Policy, March 18 2016, accessed at http://foreignpolicy.com/2016/03/18/pentagon-wasted-500-million-syrian-rebels/.

46 Shawn Snow, “Syrian Kurds Are Now Armed with Sensitive US Weaponry, and the Pentagon Denies Supplying It,” Military Times, May 7, 2017, https://www.militarytimes.com/news/your-military/2017/05/07/syrian-kurds-are-now-armed-with-sensitive-us-weaponry-and-the-pentagon-denies-supplying-it/; “Arming Iraq’s Kurds: Fighting IS, Inviting Conflict,” International Crisis Group, May 12, 2015, https://www.crisisgroup.org/middle-east-north-africa/gulf-and-arabian-peninsula/iraq/arming-iraq-s-kurds-fighting-inviting-conflict.

47 Aron Lund, “Syria’s Kurds at the Center of America’s Anti-Jihadi Strategy,” Carnegie Middle East Center, December 2, 2015, http://carnegie-mec.org/diwan/62158.

48 Sarah El Deeb, “Arabs, Kurds Unite Against IS, But Post-Victory? ‘God Knows’,” Associated Press, September 3, 2017, https://www.apnews.com/a206535243584857be53ee0d0bf94cf8.

49 Gregory Korte, “16 Times Obama Said There Would Be No Boots on the Ground in Syria,” USA Today, October 30, 2015, https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/onpolitics/2015/10/30/16-times-obama-said-there-would-no-boots-ground-syria/74869884/.

50 Paul McLeary, “Pentagon Acknowledges 2,000 Troops in Syria,” Foreign Policy, December 6, 2017, https://foreignpolicy.com/2017/12/06/pentagon-acknowledges-2000-troops-in-syria/.

51 Ryan Browne, “U.S. Special Ops Chief: More than 60,000 ISIS Fighters Killed, CNN, February 15, 2017, https://www.cnn.com/2017/02/14/politics/isis-60000-fighters-killed/index.html; Andrew Tilghman, “Why ISIS Flow of New Recruits has Slowed to a Trickle,” Military Times, April 26, 2016, https://www.militarytimes.com/2016/04/26/why-isis-flow-of-new-recruits-has-slowed-to-a-trickle/.

52 Kim Hielmgaard, “American-Backed Syrian Force Declares Victory over Islamic State,” USA Today, March 23, 2019, https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/world/2019/03/23/islamic-state-syria-american-forces-baghouz/3254079002/. On the progress against ISIS as of last fall, see Lead Inspector General for Operation Inherent Resolve: “Quarterly Report to the United States Congress, July 1, 2018–September 30, 2018,” Department of Defense Office of Inspector General, November 5, 2018, https://www.dodig.mil/Reports/Lead-Inspector-General-Reports/Article/1681560/lead-inspector-general-for-operation-inherent-resolve-i-quarterly-report-to-the/.

53 David E. Sanger, Eric Schmitt and Ben Hubbard, “Trump Ends Covert Aid to Syrian Rebels Trying to Topple Assad,” New York Times, July 19, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/07/19/world/middleeast/cia-arming-syrian-rebels.html; Jonathan Landay, “No Role for Assad in Syria’s Future: Tillerson,” Reuters, October 26, 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-mideast-crisis-syria-tillerson/no-role-for-assad-in-syrias-future-tillerson-idUSKBN1CV2GY; Amberin Zaman, “US to Ask Syrian Kurds to Let Turkish Forces through the Door,” Al-Monitor, April 15, 2019, https://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2019/04/us-ask-syria-kurds-turkish-forces-through-door.html.

54 Julian Borger, David Smith, and Jennifer Rankin, “Syria Chemical Attack has Changed My View of Assad, Says Trump,” The Guardian, April 6, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2017/apr/05/syria-chemical-gas-attack-donald-trump-nikki-haley-assad; Robin Wright, “Trump Strikes Syria Over Chemical Weapons,” New Yorker, April 13, 2018, https://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/trump-strikes-syriaand-russia-and-irannot-only-over-chemical-weapons; Susan Heavey, Makini Brice, and Tom Perry, “Trump Signals Strikes Against Syria, Lays Into Assad Ally Russia,” Reuters, April 11, 2018, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-mideast-crisis-syria/trump-signals-strikes-against-syria-lays-into-assad-ally-russia-idUSKBN1HI1BY.

55 John Hudson and Vera Bergengruen, “Tillerson Calls for Indefinite US Military Presence in Syria to Remove Assad,” Buzzfeed News, January 17, 2018, https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/johnhudson/tillerson-calls-for-indefinite-us-military-presence-in.

56 Ryan Browne and Barbara Starr, “Trump Says US Will Withdraw from Syria ‘Very Soon’,” CNN, March 29, 2018, https://www.cnn.com/2018/03/29/politics/trump-withdraw-syria-pentagon/index.html.

57 Missy Ryan, Paul Sonne, and John Hudson, “In Syria, Trump Administration Takes on a New Goal: Iranian Retreat,” Washington Post, September 30, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/in-syria-us-takes-on-new-goal-iranian-retreat/2018/09/30/625c182a-c27f-11e8-97a5-ab1e46bb3bc7_story.html; James F. Jeffrey, “Briefing on Syria,” U.S. Department of State, November 14, 2018, https://www.state.gov/r/pa/prs/ps/2018/11/287368.htm.

58 “US Accepts Assad Staying in Syria - But Won’t Give Aid,” AFP, December 17, 2018, https://www.france24.com/en/20181217-us-accepts-assad-staying-syria-but-wont-give-aid.

59 Josh Lederman and Abigail Williams, “Brett McGurk, Special Envoy for Coalition to Defeat ISIS, Resigns in Protest of Syria Decision,” NBC News, December 22, 2018, https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/politics-news/brett-mcgurk-special-envoy-coalition-defeat-isis-resigns-protest-syria-n951251.

60 Jeremy Diamond and Elise Labott, “Trump Told Turkey’s Erdogan in Dec. 14 Call About Syria, ‘It’s All Yours. We Are Done’,” CNN, December 24, 2018, https://www.cnn.com/2018/12/23/politics/donald-trump-erdogan-turkey/index.html.

61 Steven T. Dennis, “Trump’s Syria Decision ‘Rattled the World,’ Graham Says,” Bloomberg, December 20, 2018, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-12-20/trump-s-syria-decision-rattled-the-world-gop-s-graham-says; Caitlin Oprysko, “Trump Defends Surprise Syria Withdrawal Despite Withering GOP Criticism,” Politico, December 20, 2018, https://www.politico.com/story/2018/12/20/trump-defends-syria-withdrawal-1070943; Jamie Ross, “‘Fox & Friends’ Slams Trump on Syria Withdrawal: Only a Child Would Think ISIS Is Defeated,” The Daily Beast, December 20, 2018, https://www.thedailybeast.com/fox-and-friends-slams-trump-on-syria-withdrawal-only-kids-think-isis-is-defeated.

62 Eric Schmitt and Maggie Haberman, “Trump to Allow Months for Troop Withdrawal in Syria, Officials Say,” New York Times, December 31, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/31/us/politics/trump-troop-withdrawal-syria-months.html; Karen DeYoung and Karoun Demirjian, “Contradicting Trump, Bolton Says No Withdrawal From Syria Until ISIS Destroyed, Kurds’ Safety Guaranteed,” Washington Post, January 6, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/bolton-promises-no-troop-withdrawal-from-syria-until-isis-contained-kurds-safety-guaranteed/2019/01/06/ee219bba-11c5-11e9-b6ad-9cfd62dbb0a8_story.html.

63 Courtney Kube, “ISIS Regrouping in Iraq, Pentagon Report Says,” NBC News, February 4, 2019, https://www.nbcnews.com/news/mideast/isis-regrouping-iraq-pentagon-report-says-n966771; Sarah Westwood and Devan Cole, “Trump Says He Would Send US Troops Back to Syria Should ISIS Regain Strength,” CNN, February 3, 2019, https://www.cnn.com/2019/02/03/politics/trump-syria-troops-isis/index.html.

64 Matthew S. Schwartz and Richard Gonzales, “U.S. Will Leave 400 Troops In Syria,” NPR, February 22, 2019, https://www.npr.org/2019/02/22/696928907/u-s-will-leave-200-peacekeeping-troops-in-syria.

65 David Ignatius, “How the U.S. Might Stay in Syria, and Leave at the Same Time,” Washington Post, February 15, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2019/02/15/how-us-might-stay-syria-leave-same-time/.

66 Glass, “‘Tell Me How This Ends.’”

67 Quoted in Glass, “‘Tell Me How This Ends.’”

68 Benjamin H. Friedman, “Intervention in Libya and Syria Isn’t Humanitarian or Liberal,” The National Interest, April 5, 2012, https://nationalinterest.org/blog/the-skeptics/intervention-libya-syria-isn%E2%80%99t-humanitarian-or-liberal-6739; Brian T. Haggerty, “The Delusion of Limited Intervention in Syria,” Bloomberg, October 4, 2012; Spencer Ackerman, “Even with U.S. Guns, Syria’s Rebels Still Might Lose,” Danger Room, May 3, 2013; Ted Galen Carpenter, “Tangled Web: The Syrian Civil War and Its Implications,” Mediterranean Quarterly 24, no. 1 (Spring 2013): 1–11; Erica D. Borghard, “Arms and Influence in Syria: The Pitfalls of Greater U.S. Involvement,” Cato Policy Analysis no. 734, August 7, 2013, https://object.cato.org/sites/cato.org/files/pubs/pdf/pa734_web_1.pdf.

69 Ben Taub, “Iraq’s Post-ISIS Campaign of Revenge,” New Yorker, December 24 & 31, 2018, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/12/24/iraqs-post-isis-campaign-of-revenge.

70 Liz Sly, “U.S. Troops May Be At Risk of ‘Mission Creep’ After a Deadly Battle in the Syrian Desert,” Washington Post, February 8, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/middle_east/syria-accuses-us-of-aggression-after-its-warplanes-strike-pro-government-forces/2018/02/08/bab1502a-0cb4-11e8-8890-372e2047c935_story.html.

71 Ford, “Keeping Out of Syria,” 19.

72 Thomas Gibbons-Neff, “How a 4-Hour Battle Between Russian Mercenaries and U.S. Commandos Unfolded in Syria,” New York Times, May 24, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/24/world/middleeast/american-commandos-russian-mercenaries-syria.html.

73 Ambassador James F. Jeffrey, “Interview with RIA Novosti and Kommersant,” November 21, 2018, https://ru.usembassy.gov/special-representative-for-syria-engagement-jeffrey-in-interview-with-ria-novosti-and-kommersant/.

74 Ben Hubbard and David M. Halbfinger, “Iran-Israel Conflict Escalates in Shadow of Syrian Civil War,” New York Times, April 9, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/09/world/middleeast/syria-russia-israel-air-base.html; Herb Keinon, “Netanyahu: Israel Will Hit Iran Throughout Syria, Not Only Along Border,” Jerusalem Post, June 17, 2018.

75 “Israel Strikes Iranian Forces in Syria after Iran ‘Shells Golan Heights’,” France24, May 5, 2018, https://www.france24.com/en/20180510-iran-forces-syria-shell-israel-military-golan-heights.

76 Paul Iddon, “Idlib Offensive All But Inevitable for Turkey,” Ahval News, January 30, 2019, https://ahvalnews.com/syrian-war/idlib-offensive-all-inevitable-turkey.

77 Richard Pérez-Peña, “Erdogan Says Turkey Will Delay Assault on Kurds and ISIS in Syria,” New York Times, December 21, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/21/world/middleeast/turkey-military-syria.html.

78 Aaron Stein, “What’s the Matter in Manbij? How an Obscure Syrian Town Could Determine the Future of the U.S.-Turkish Alliance and What to Do about It,” War on the Rocks, May 21, 2018, https://warontherocks.com/2018/05/whats-the-matter-in-manbij-how-an-obscure-syrian-town-could-determine-the-future-of-the-u-s-turkish-alliance-and-what-to-do-about-it/.

79 Kyle Rempker, “US Troops in Syria Take Fire from Turkish Proxy Fighters,” Military Times, October 24, 2018, https://www.militarytimes.com/news/your-military/2018/10/24/us-troops-in-syria-take-take-fire-from-turkish-proxy-fighters/.

80 Benjamin H. Friedman, “Review of Terror on the Internet: The New Arena, the New Challenges by Gabriel Weimann,” Political Science Quarterly 122, no. 1, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/j.1538-165X.2007.tb01599.x.

81 Holly Yan, “How Is ISIS Luring Westerners?” CNN, March 23, 2015, https://www.cnn.com/2015/03/23/world/isis-luring-westerners/index.html; Max Abrahms, “The Political Effectiveness of Terrorism Revisited,” Comparative Political Studies 45, no. 3 (March 2012): 366-393, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0010414011433104.

82 James Quinlivan, “Force Requirements in Stability Operations,” Parameters 25, no. 4 (Winter 1995–1996) 59–69.

83 “Operation Inherent Resolve and Other Overseas Contingency Operations,” Report of the Lead Inspector General to Congress, July 1 2018-September 30, 2018, https://media.defense.gov/2018/Nov/05/2002059226/-1/-1/1/FY2019_LIG_OCO_OIR_Q4_SEP2018.pdf

84 Ben Hubbard, “U.S.-Backed Forces in Syria Arrest Suspects in Attack That Killed 4 Americans,” New York Times, March 19, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/19/world/middleeast/syria-bombing-suspects-arrest.html. For a particularly expansive idea of the what the United States attempt in Syria from the top U.S. official there, see “Testimony of James F. Jeffrey to the House Foreign Affairs Committee,” November 29, 2018, https://docs.house.gov/meetings/FA/FA13/20181129/108766/HHRG-115-FA13-Wstate-JeffreyJ-20181129.pdf.

85 Benjamin Denison, “Confusion in the Pivot: the Muddled Shift from Peripheral War to Great Power Competition,” War on the Rocks, February 12, 2019, https://warontherocks.com/2019/02/confusion-in-the-pivot-the-muddled-shift-from-peripheral-war-to-great-power-competition/.

86 Robert Pape, Dying to Win: The Strategic Logic of Suicide Terrorism (New York: Random House, 2005).

87 See, for example, the remarks of James Jeffrey at the Atlantic Council, “The Future of U.S. Policy in Syria,” December 17, 2018.

88 On cumulative gains and their absence in place like Syria, see Stephen Van Evera, “Why Europe Matters, Why the Third World Doesn’t: American Grand Strategy after the Cold War,” Journal of Strategic Studies 13, no. 2 (June 1990): 1–51.

89 Ford, “Keeping out of Syria,” 19.

90 Patrick Clawson, Hanin Ghaddar, and Nader Uskowi, “What is the Shia Crescent?,” Washington Institute for Near East Policy, January 17, 2018, https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/view/middle-east-faqs-volume-1-what-is-the-shia-crescent.

91 Daniel L. Byman, “Is Hezbollah Less Dangerous to the U.S.?” Brookings Institution, October 18, 2016, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/markaz/2016/10/18/is-hezbollah-less-dangerous-to-the-united-states/.

92 Ian Black, “Syria’s Disintegration Alarms Israel,” The Guardian, February 14, 2014, https://www.theguardian.com/world/on-the-middle-east/2014/feb/14/israel-syria-alqaida-golan.

93 Tom Perry, “Syrian Kurdish-backed Council Holds Talks in Damascus,” Reuters, July 27, 2018, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-mideast-crisis-syria-talks/syrian-kurdish-backed-council-holds-talks-in-damascus-idUSKBN1KH0Q9.

94 Robert S. Ford, “Trump’s Syria Decision Was Essentially Correct. Here’s How He Can Make The Most of It,” Washington Post, December 27, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/even-without-troops-the-us-can-still-have-influence-in-syria/2018/12/27/757582b8-0a08-11e9-85b6-41c0fe0c5b8f_story.html; Benjamin H. Friedman and Justin Logan, “Trump Is Right to Withdraw US Troops From Syria. We’ve Done Our Job by Defeating ISIS,” USA Today, December 20, 2018, https://www.usatoday.com/story/opinion/2018/12/20/donald-trump-decision-withdraw-troops-syria-lowers-risks-costs-column/2374266002/.

95 Andrew Wilks, “Bolton in Turkey to Hammer out Deal for Syria’s Kurdish Fighters,” Al Jazeera, January 7, 2019, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/01/bolton-heads-turkey-hammer-deal-syria-kurds-190106180228619.html.

96 Rodi Said, “Syrian Kurds Seek Damascus Deal regardless of U.S. Moves,” Reuters, January 4, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-mideast-crisis-syria-kurds/syrian-kurds-seek-damascus-deal-regardless-of-us-moves-idUSKCN1OY1ET.

97 Rana Khalaf, “Governing Rojava: Layers of Legitimacy in Syria,” Middle East and North Africa Programme, Chatham House, December 2016, https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/publications/research/2016-12-08-governing-rojava-khalaf.pdf.

98 Matt Spetalnick and Francois Murphy, “U.S. sticks to Demand Assad Leave Power at First Peace Talks to Include Iran,” Reuters, October 30, 2015, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-mideast-crisis-syria-talks-idUSKCN0SN1SS20151030; Vladimir Isachenkov, “Syrian Official Rejects US Demand for Iranian Withdrawal,” AP News, May 23, 2018, https://apnews.com/0ad489c52ae44f4a8aa31e4643d7276f.